Lotto carpet

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Lorenzo Lotto “ The Alms of St. Anthony ”, 1542, with two carpets. In the foreground a “Lotto carpet”, in the background a so-called “Para-Mamluk carpet”.

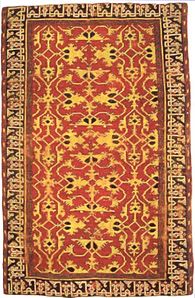

Right picture : “Lotto carpet”, Saint Louis Art Museum . The balanced composition of the field and the open "kufic" border support the dating back to the 16th century. |

||

In the history of art, the term Lotto carpet describes a special type of antique Anatolian knotted carpets , which are characterized by a common color and pattern design. They were made in Western Anatolia in the 16th and 17th centuries , but also in Italy, Spain, Rumelia (the European part of the Ottoman Empire ) and England. Technical similarities with carpets made for trade in the Uşak region indicate that most of the “Lotto” carpets come from this region. Modern copies of the decorative carpet pattern are also known.

Origin of the term

The name was coined by European art historians of the 19th century: Richly designed Islamic carpets made their way to Western Europe in large numbers as commercial goods from the 14th century and exerted a great influence on the painters of the Renaissance . When European art scholars began to study oriental carpets as an important product of Islamic art towards the end of the 19th century , only a few preserved antique carpets were known. Therefore, research initially focused on the carpets depicted in paintings from the Renaissance period . To classify the various carpet styles and to facilitate understanding, the names of the Renaissance painters were used, on whose paintings the carpets were found. Originally, the carpets were classified as "small patterned Holbein carpets of type II". Hans Holbein the Younger , however, never painted such a carpet himself. The northern Italian painter Lorenzo Lotto (1480–1557) depicted such a carpet in his painting “The Alms of St. Anthony”; his name has therefore established itself for the carpet type in art-historical parlance.

Pattern design

Field pattern

|

|

|

|

Left picture : "Lotto carpet", Anatolia, 16th century, Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art , Istanbul

Right picture : "Lotto carpet", detailed view of the field |

||

The field of a lottery carpet usually has a red background and is decorated with bright yellow fork leaf and flower ornaments. A repeat pattern of geometric, cruciform, octagonal or diamond-shaped ornaments lies on top of it, arranged vertically in horizontal rows. Carpets of various sizes up to 6 m² have been preserved. Charles G. Ellis distinguishes three main groups of the "Lotto" pattern: the "Anatolian", "Kelim" and the "ornamental" style. According to Ellis, the pattern was probably created by adapting an originally curvilinear model to the technique of knotting carpets with symmetrical knots, which is more suitable for rectilinear, geometric design.

“Lotto” carpet patterns have little in common with the decorative patterns and ornaments seen on other objects of Ottoman art. Briggs showed similarities between these two types of carpets and those depicted on Timurid book illuminations. The pattern tradition of the "Lotto" carpets could therefore go back to the Timurid period.

Border pattern

While the characteristic field pattern remained largely unchanged, the design of the border pattern changed over time so that it can be used to determine the age of a "Lotto" carpet: The earliest and rarest carpets of the "Lotto" type have a geometric border pattern , which is made of a calligraphic braided band in white on a blue background and consists of a sequence of repeated, long and short arrowhead-like ornaments. The ligatures of the vertical elements end in beveled tips. Because of their similarity to the letters alif and lām of the Kufi script, this border pattern is called “kufic”, or “pseudo-kufic” if no similarity to the characters is recognizable. These two letters are supposed to represent a short form of the word " Allah ". The "alif-lām" motif can already be found on Anatolian carpets from the Eşrefoğlu mosque in Beyşehir , which date from the 13th century.

A further development step in the pattern design of the "Lotto" carpet is the reshaping of the border ornament into the so-called "closed" Kufic border. The geometric border is now simplified and presented more compact, the font motif appears more intertwined, the ligatures protrude less. This border design can also be found in other types of carpets such as the small-sized “Holbein” carpets, which were also manufactured in the region around Uşak and exported to Europe.

Even later carpets of the "Lotto" type have different border patterns that are also known from other types of carpets. For example, the so-called “jagged palmette pattern” was widespread from the 17th century and first appears in a Western European painting in Caravaggio's Last Supper in Emmaus from 1601.

Towards the end of the 17th century, the simple "cartouche" borders, as well as the field design, which only reproduces a section of the cross-and-octagon pattern with standardized ornament sizes, characterize mass production. Probably in connection with the declining interest of the European market, the lottery pattern is disappearing; after the 17th century there are no more carpets with a lottery pattern.

European art history

“Lotto” -type carpets are first depicted in Italy since 1516, in Portugal about a decade later, and in Northern Europe including England during the 1560s. They still appear on paintings until the 1660s, especially in Dutch painting. They were particularly popular as votive offerings in Central Europe , and there are numerous examples among the Transylvanian carpets . The collections of the Margaret Church in Mediaş and the Black Church of Braşov in Romania have - along with other Transylvanian fortified churches - the largest number of these carpets in Europe. The Museo Nazionale del Bargello , the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Saint Louis Art Museum keep well-preserved “Lotto” carpets.

literature

- Charles Grant Ellis: The "Lotto" pattern as a fashion in carpets. In: Festschrift for Peter Wilhelm Meister. Hauswedell, Hamburg 1975, p. 19-31 .

- Donald King and David Sylvester (Eds.): The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, From the 15th to the 17th century , Arts Council of Great Britain, London, 1983, ISBN 0-7287-0362-9

- Rosamond E. Mack: Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600 , Los Angeles, University of California Press, 2002.

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ King and Sylvester, pp. 16, 67–70.

- ↑ Kurt Erdmann : Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpet . Busse, Herford 1966.

- ^ A b Charles Grant Ellis: The "Lotto" pattern as a fashion in carpets. In: Festschrift for Peter Wilhelm Meister. Hauswedell, Hamburg 1975, p. 19-31 .

- ^ Friedrich Spuhler: Carpets from Islamic Lands . 1st edition. Thames & Hudson, London 2012, ISBN 978-0-500-97043-0 .

- ↑ Amy Briggs: Timurid Carpets; I. Geometric carpets . In: Ars Islamica . 7, 1940. pp. 20-54

- ↑ Belkıs Balpınar, Udo Hirsch: Carpets of the Vakiflar Museum Istanbul = carpets of the Vakiflar Museum Istanbul . U. Hülsey, Wesel 1988, ISBN 3-923185-04-9 , pp. 12-14 .

- ^ Walter B. Denny: Lotto Carpets. In: Walter B. Denny, Thomas J. Farnham: The carpet and the connoisseur: The James F. Ballard Collection of Oriental Rugs . Hali Publications Ltd., London 2016, ISBN 978-0-89178-072-4 , pp. 73-75 .

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 67