Oriental carpets in renaissance painting

From the 13th to the 17th century, oriental carpets were repeatedly depicted as a decorative element in Western European paintings from the Renaissance period . There are even more oriental carpets depicted in the Renaissance painting than are known to have been preserved. Since research on Islamic carpet art began in the late 19th century, comparative Islamic art studies have therefore relied on carpet depictions in European paintings, the time of which has been documented. The examination of the paintings thus made an important contribution to Islamic art history, in particular to the chronology of the knotted carpets as a medium of Islamic art .

|

|

|

|

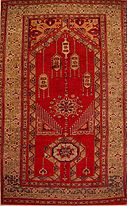

Left picture : An Islamic carpet of the "Bellini type" at the feet of Mary , in Gentile Bellini's Enthroned Madonna and Child , late 15th century.

Right picture : Prayer rug, Anatolia , late 15th - early 16th century, with "keyhole" - motif. |

||

Art history background

In the late 19th century, art historians and collectors began to take an interest in Islamic carpets. This has significantly increased the number of known pieces that have survived. It was now possible to compare the present carpets in detail with their painted counterparts and to place them in chronological order. This resulted in an increasingly detailed presentation of the cultural history of Islamic carpet weaving. Scientific interest in the countries of origin was also awakened, which led to the identification of further antique carpets in the museums and collections there and expanded knowledge of cultural history.

The western artistic tradition of precise, realistic reproduction, as it was especially cultivated in the late 15th and 16th centuries in the Netherlands , provides research with visual material that allows even the finest details of the carpets shown to be evaluated. The carpets were reproduced with extraordinary care, both in terms of color and the details of their shape and pattern: the painted structure of the carpet in Virgin and Child by Peter Christ , the drawing of the individual ornaments and patterns and the way the pile adapts to the The edges of the steps leave no doubt that the carpet shown is an Islamic knotted carpet.

The task of the painted carpets is either to draw the viewer's attention to an important depicted person, or to highlight a place where an important action takes place. In parallel with the development of Renaissance art in general, mostly Christian saints and religious scenes were initially depicted. Later carpets were also depicted in a secular context, but in each case they served to convey an idea of opulence, exoticism, luxury, prosperity or status. Initially, it was reserved for the most powerful and wealthy, the ruling family and the nobility, to have themselves portrayed on carpets. Later, when more people had enough wealth to be able to afford luxury goods, oriental carpets also appeared in the pictures of wealthy merchants and wealthy citizens. During the 17th and 18th centuries, interest in depictions on carpets waned. At the same time, the paintings also show less attention to detail.

The richly designed Islamic carpets exerted a great influence on European painters. According to a hypothesis by Erdmann, their diverse, lush colors may have influenced the great Venetian painters of the Quattrocento . It is even believed that the pictorial depiction of carpet patterns is related to the development of linear perspective, which was first described by Leon Battista Alberti in 1435 .

The depiction of oriental carpets on Renaissance paintings is seen as an important contribution to a “world history of art” that examines the interaction of different cultural traditions. Carpets from the Islamic world were exported to Western Europe in large numbers from the 15th century. The 15th century is increasingly seen as a crucial hub in the cultural encounters that led to the development of the ideas, art, and science of the Renaissance era. More intensive contacts, especially the increasing trade between the Islamic world and Western Europe, made material sources and cultural influences available to Western artists over the next centuries. Conversely, the needs of the European market also had a decisive influence on Islamic handicrafts.

Comparative research

In 1871 Julius Lessing published his book Old Oriental Carpet Patterns . In it he mainly referred to European paintings and less to preserved carpets, because these were not yet specifically collected at the time and he assumed that hardly any copies had survived. Lessing's research approach proved to be extremely fruitful in creating a scientific chronology of the handicraft of carpet-knotting. It was followed up by the art scholars of the "Berlin School". Wilhelm von Bode and his successors Friedrich Sarre , Ernst Kühnel , especially Kurt Erdmann , developed the terminus ante quem method for dating Islamic carpets based on their depiction on paintings from the Renaissance period. A second important source was the representation of carpets on Turkish and Persian miniatures and illuminations . The larger format of the European pictures compared to the miniature paintings allows a more detailed and exact reproduction of the carpets and thus more reliable comparative studies.

The art historians were aware that their research approach was one-sided: during the Renaissance period, only carpets that had been made in the great manufactories of Anatolia during the Ottoman Empire and later in other countries were made in Europe. Often the carpets were specially produced for export. As a result, the Renaissance artists basically had only a limited selection of models available. The carpets from village or nomadic production, which are of cultural history, were unknown in Europe at the time of the Renaissance and were therefore never depicted in paintings. It was not until the middle of the 20th century that collectors such as Joseph V. McMullan and James F. Ballard recognized their artistic and cultural-historical value.

overview

![Left picture: Domenico di Bartolo's wedding of the boulders, 1440, shows a large carpet with a phoenix and dragon pattern based on the Chinese model. [8] Right picture: "Phoenix-and-Dragon" carpet, first half or mid-15th century. Museum for Islamic Art, Berlin. [9] [10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/Domenico_di_Bartolo_The_Marriage_of_the_Foundlings_1440.jpg/260px-Domenico_di_Bartolo_The_Marriage_of_the_Foundlings_1440.jpg)

|

![Left picture: Domenico di Bartolo's wedding of the boulders, 1440, shows a large carpet with a phoenix and dragon pattern based on the Chinese model. [8] Right picture: "Phoenix-and-Dragon" carpet, first half or mid-15th century. Museum for Islamic Art, Berlin. [9] [10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1d/Phoenix_and_dragon_carpet_Anatolia_first_half_or_middle_15th_century.jpg/150px-Phoenix_and_dragon_carpet_Anatolia_first_half_or_middle_15th_century.jpg)

|

|

|

Left picture : Domenico di Bartolo's wedding of the boulders , 1440, shows a large carpet with a phoenix- and- dragon pattern based on the Chinese model.

Right picture : “Phoenix-and-Dragon” carpet, first half or mid-15th century. Museum of Islamic Art , Berlin. |

||

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Lippo Memmis Virgin Mary with Child , 1340–1350 shows an animal carpet with two birds facing each other next to a tree.

Right picture : Anatolian animal carpet, approx. 1500, from the church of Marby, Sweden |

||

Knotted carpets in geometric patterns have been made in Eastern Anatolia at least since the time of the Rum Seljuks in the 13th century . Venice had trade relations with the sultanate since around 1220. The Venetian trader and traveler Marco Polo mentions carpets from Konya , the capital of the Seljuk Empire, as the most beautiful in the world:

[…] Et ibi fiunt soriani et tapeti pulchriores de mundo et pulchrioris coloris.

"[...] and here they make the most beautiful silk fabrics and carpets in the world, in the most beautiful colors."

The majority of the carpets in paintings of the 15th and 16th centuries either come from the Ottoman Empire, or are perhaps European imitations from the Balkans, Spain, or other countries where carpets are known to have been knotted at that time. In fact, not the finest Islamic carpets from this period made it to Europe, and only a few of the highest quality carpets from the court manufactories can be seen on paintings. Persian rugs did not appear on paintings until the late 16th century, but became increasingly popular with the very wealthy in the 17th century. Mamluk carpets are occasionally depicted, especially on Venetian and only rarely on Northern European paintings.

One of the earliest depictions of an Islamic carpet on a European picture is Simone Martini's Saint Ludwig of Toulouse crowning Robert of Anjou as King of Naples , painted between 1316 and 1319. In direct comparison with the few surviving carpets from this period, most of the European pictures show the carpets quite lifelike again.

Most carpets at this time were designed in an Islamic geometric pattern. The earliest carpets depict the animal patterns of early Anatolian carpets . The “phoenix and dragon” carpet, today in the Museum of Islamic Art , Berlin, has a counterpart in Domenico di Bartolo's Wedding of the Erratic Boulders (1440). With the adoption in the pattern repertoire of Islamic art, the depicted animals have been stylized in a strong geometric manner. The group of Anatolian animal carpets disappeared from the paintings towards the end of the 15th century. Only a few originals of this group of carpets have survived, two of them were in European churches. The Marby carpet, one of the best-preserved examples, has survived in a church in Sweden , the "Phoenix and Dragon" carpet was purchased by Wilhelm von Bode from an Italian church. The “Phoenix and Dragon” and the “Marby” carpets were the only surviving carpets in this group until 1988. Seven more animal rugs have appeared since then. They come from Tibetan monasteries and were taken away by the monks when they fled the Chinese Cultural Revolution to Nepal. One of the carpets was purchased from the Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York. It has a counterpart in a picture by the Sienese artist Gregorio di Cecco : The Marriage of the Virgin , 1423. It shows large animals facing each other, each with a smaller animal in it.

Most of the carpets in the paintings are reserved for the main characters depicted, often Maria or saints , who are painted, for example, on a pedestal, in front of an altar or on a throne around the main character. A typical example of this is the Turkish carpet at the feet of the Virgin Mary on Andrea Mantegna's San Zeno altar from 1456-1459 in San Zeno Maggiore .

The donors of the paintings sometimes also appear as secondary characters, who are either small in the tradition of the perspective of meaning and depicted on the edge of the picture, later also more self-confidently directly on the carpet and as large as the main character. Religious iconography was also adopted by the rulers, who were depicted on oriental carpets. A Safavid carpet from the 16th century is still used today in Denmark as a "coronation carpet " in the ritual of the coronation of the Danish kings . Oriental carpets are also depicted as house decorations on special occasions, for example on the occasion of processions, such as in the pictures of the Venetian painters Vittore Carpaccio and Gentile Bellini . On Carpaccio's embarkation of St. Ursula, the carpets adorn the walls of the ship and the gangplank.

Oriental carpets were known by trade names in Renaissance Italy: Mamluk carpets from Cairo were called cagiarini , those from Damascus were called damaschini , barbareschi from North Africa, rhodioti and turcheschi from the Ottoman Empire, and carpets from the Caucasus were known as simiscasa .

In the 16th century, the depiction of oriental carpets as a symbol of luxury, status and good taste was part of the formal canon of bourgeois portraits. after broader strata of the population had achieved economic prosperity and were able to afford luxury items. Some painters, such as Gentile Bellini, who was a member of an embassy at the Sultan's court in Istanbul , paint pictures in the early orientalist style. Some of the pictures with a religious subject show carpets that were also used as prayer carpets in Islamic culture and use motifs such as the mihrab niche or the Kaaba . The latter in the form of the so-called “re-entry” motif are also known as “Bellini” carpets. Carpets with prayer niche motifs were exported to Europe in large numbers until the 17th century.

In northern and especially in Dutch painting of the Golden Age , middle-class people tend to place an oriental carpet on a table or piece of furniture, instead of standing on it like kings and the nobility. A well-known example of this is Holbein's portrait of the businessman Georg Giese . Sometimes carpets lie on the floor, for example in Jan van Eyck's painting Arnolfini's Wedding from 1434. In later times carpets appear in an allegorical context as a symbol of luxury or debauchery, as in Jan Vermeer's Bei der Couplerin from 1656, often in the same sense in still life painting . As a luxury item, the oriental carpet can finally be found in the vanitas still lifes of the 17th century. With the end of the Renaissance period and the transition into new stylistic epochs, the interest of European painters in depicting oriental carpets, which had remained alive for more than three centuries, also died out.

Carpet patterns named after artists

|

|

|

|

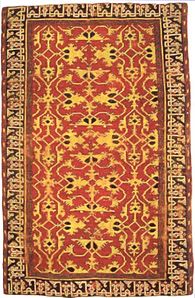

Left picture : Lorenzo Lotto husband with wife , 1523 with a "Bellini" carpet with a keyhole motif.

Right picture : Prayer rug with “keyhole” pattern, Anatolia, late 15th – early 16th century. |

||

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Carlo Crivelli Annunciation with St. Emidius , 1486, with a “Crivelli” carpet in the upper left corner. A second carpet above in the middle,

right picture : “Crivelli” carpet, Anatolia, late 15th century. |

||

At the beginning of research into the history of art, various types of carpet patterns were named after the European artists who depicted carpets with such patterns in their paintings to make them easier to understand. This classification continued to be used as more detailed information became available. The classification of artist names goes back mainly to Kurt Erdmann , the former director of the Museum for Islamic Art , Berlin, and one of the leading Islamic art scholars of his time.

Some carpet designs have not been used for centuries and their origins remain unclear, so more suitable alternative names are not yet available. The classification is essentially based on the dominant motifs of the field and differentiates according to type, size and arrangement of the patterns and motifs. The assignment to European painters sometimes seems arbitrary, since on the one hand different artists have depicted the same type of carpet, on the other hand patterns are even assigned to painters who have actually never painted them.

Bellini carpets

Giovanni Bellini and his brother Gentile ( sent to Istanbul in 1479 ) painted prayer rugs with a single "keyhole" or "re-entry" motif at the bottom of a larger figure. It is separated from the field by a narrow border. At the upper end, this border converges diagonally to form a point or niche, from which an ornament similar to a lamp often hangs down. This pattern was and is of great importance in the design of Islamic prayer rugs . This seems to have been known in Europe, because in English of that time carpets were with this pattern as a musket carpets refers to a corruption of the word mosque , mosque ' .

In Gentile Bellini's Enthroned Madonna and Child , the carpet is right in terms of motifs, namely just like a Muslim would use a prayer carpet: facing the prayer niche that the qibla indicates. This is not the case with Lorenzo Lotto's husband and wife from 1523. Here the couple turns to the "foot end" of the carpet. It is not known whether Bellini saw and understood how prayer rugs are used in Istanbul.

Uşak carpets with double niches at the top and bottom are sometimes called " Tintoretto " carpets. But the name is not very common.

Crivelli carpets

Carlo Crivelli may have painted the same little rug twice. The center of the field is taken up by a complex 16-pointed star motif that is composed of several segments in different colors. Some pattern elements contain highly stylized depictions of animals. Comparable preserved carpets are very rare. Two copies are kept in the Hungarian Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest , including the so-called "Batári-Crivelli" fragment shown. Crivelli's picture Annunciation from 1482 in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt shows a similar carpet in the upper part of the picture. The same or a very similar carpet is also found in the Annunciation with St Emidius , 1486, National Gallery , London. The carpet here hangs over a balcony in the upper left area of the picture. Another, different type of carpet is shown in the foreground on the right. These carpets evidently represent a transition type between the early animal carpets and later purely geometric patterns, as can be seen on the “Holbein” carpets. It is assumed that this pattern change is due to the increased attention to the ban on images in the Ottoman Empire .

Memling carpets

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Hans Memling , Virgin with Child and Saints James and Dominic , 1488–1490. The hook medallion marks the "Memling" carpet.

Right picture : Carpet from Konya , 18th century with “Memling” medallions |

||

Hans Memling painted various carpets which are dated to the last quarter of the 15th century. Characteristic of these carpets are rows of medallions, which are decorated with hook ornaments, which curl up in two or three 90 ° angles in a characteristic way. A “Memling” carpet also appears on a miniature that was painted around 1460 for René I of Anjou .

Holbein carpets

"Holbein" carpets are already depicted in paintings that were painted decades before Holbein . Probably the oldest representation can be found on a fresco by Piero della Francesca in the Cathedral of Rimini from 1451. A similar representation on the altar of San Zeno, Verona, by Andrea Mantegna comes from 1460 . The latest known representations are those at the conference in Somerset House from 1608 and a female portrait by Justus Sustermans dated 1655 . “Holbein” carpets were thus depicted in paintings for almost 200 years. Characteristic for this group is a pattern of rows of octagons with an inwardly intertwined contour, alternating with offset rows of diamond-shaped figures, the contour of which is formed by arabesque leaves that extend from a cross-shaped central motif. The complicated pattern of some carpets also allows the following reading: It is made up of small, rhythmically changing color squares with octagon fillings and corner bevels.

The carpets were divided into four types. Holbein himself only painted the lavish types III and IV, for example in the portrait of the merchant Georg Giese (1532) and in the picture The Ambassadors (1533). Nevertheless, the name “Holbein Carpet” was retained among collectors and art historians for convenience and for easier communication. In fact, "Holbein" patterns are among the most common carpet patterns shown on Renaissance paintings and have been depicted repeatedly over a long period of time. The types of "Holbein" carpets are:

Type I (small-sized)

The motifs of this type of carpet are small and consist of regular rows of braided motifs derived from octagons with an inner star in a square setting and stylized tendrils at the intersections. The border usually has a delicately intertwined bandwork in white on a colored background, initially in imitation of Kufic letters, later as a pure bar structure. The colors are strong, mostly on a dark red background. An example of a small-sized Holbein rug can be found on the group portrait of the Somerset House conference .

Type II (today: "Lotto" carpets)

Today these carpets are called Lotto carpets .

Type III (large-faced)

The motifs in the field are similar to those of the small-sized type, but larger in proportion, so that the field is filled with a few stars in octagon mounts. The large stars or diamonds are arranged at regular intervals and separated by narrow strips. The square sections do not have a medallion ( gül ). The carpet in Holbein's painting Die Messengers shows this type.

Type IV (large-figured)

The square sections contain similar octagons or “Gül” motifs as on the small-sized Holbein carpets. In contrast to the other three types, whose ornaments are arranged side by side with the same rank and size, the Type IV pattern consists of one significantly larger and four smaller ornaments. This pattern arrangement is also known as a " quincunx " pattern.

Lotto rugs

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Lorenzo Lotto The Alms of St. Anthony , 1542, with two carpets. In the foreground a “Lotto carpet”, in the background a so-called “Para-Mamluk carpet”.

Right picture : “Lotto carpet”, Anatolia, 16th century, Saint Louis Art Museum |

||

“Lotto” carpets were originally classified as “small-patterned Holbein type II carpets”. Hans Holbein the Younger , however, never painted such a carpet himself. They appear several times in pictures by Lorenzo Lotto , after whom they are named, but have already been depicted in earlier pictures by other painters. Lotto is also known to own a large carpet, which type is unknown. "Lotto" carpets were mainly produced during the 16th and 17th centuries in the area of the western Anatolian Aegean coast , but were also imitated in various European countries, including Spain, England and Italy.

The carpets are characterized by a characteristic geometric arabesque pattern , which form a bright yellow grid in the form of cross-shaped, octagonal or diamond-shaped medallions arranged alternately in a repeat on a red field. "Lotto" carpets of various sizes, up to 6 m², have been preserved. CG Ellis distinguishes three main groups of her pattern: the "Anatolian", "Kilim" and "ornamental" style. Both “Holbein” and “Lotto” carpets have little in common with decorations or ornaments as seen on other objects of Ottoman art. Briggs pointed out similarities between both carpet patterns and carpets on miniatures from the Timurid period. It is conceivable that "Holbein" and "Lotto" carpets stem from a pattern tradition that goes back to the Timurid period.

According to the paintings, carpets of this type reached Italy around 1516, Portugal about a decade later, and Northern Europe including England during the 1560s. They still appear on paintings until the 1660s, especially in Dutch painting.

Ghirlandaio carpets

A carpet very similar to a painting by Domenico Ghirlandaio from 1483 was found by A. Boralevi in the Evangelical Church of Hâlchiu (Heldsdorf) in Transylvania . The carpet probably comes from Western Anatolia and can be dated to the late 15th century.

The pattern of the Ghirlandaio-type carpets, as it is shown in another picture from 1486, is closely related to the carpets of the "Holbein" type I. It is characterized by one or two diamond-shaped central medallions, made up of an octagon within a square, with triangular, curvilinear patterns extending from the sides. Carpets with such medallions have been made in the western Anatolian province of Çanakkale since the 16th century . A fragment of carpet with a “Ghirlandaio” medallion was also found in the Great Mosque of Divriği , and dates to the 16th century. Carpets of this type are also known from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries and are still made in the Turkish province of Çanakkale today.

In his essay on Centralized Designs , Thompson relates the central medallion of oriental carpets to the "lotus pedestal" and "cloud collar" motifs of Buddhist art . The origin of this motif could therefore be in pre-Islamic times. It probably dates from the time of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in China. Brüggemann and Boehmer developed this theory further and assume that the motif was brought to Anatolia by the Seljuks, or the Mongol invaders, in the 11th or 13th century. In contrast to the widely varied patterns of other carpets, the pattern of the “Ghirlandaio” medallion was largely unchanged from the 15th century to the present day. Thus it represents an unusual example of pattern continuity within a region.

Van Eyck and Petrus Christ: Painted carpets with no known counterparts

The Dutch painters Jan van Eyck and Petrus Christus have in their pictures Madonna of Canon van der Paele , Lucca-Madonna , on the Dresden Marienaltar (van Eyck), as well as the Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome and Francis (P. Christ), four different ones painted similar carpets. The realistic painting style of the pictures leaves no doubt that these are knotted carpets. However, comparable carpets have not been preserved.

The carpet pattern on van Eyck's Paele Madonna could be traced back to late Roman origins and is related to early Islamic floor mosaics in the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar . The carpets on the Lucca Madonna , the Dresden Altar of Mary , and on the Virgin with Child and Saints are strikingly similar, but not identical. They show geometric patterns with a diamond composition in an infinite repeat, made up of narrow ribbons containing eight-pointed stars. Yetkin has identified an Anatolian carpet in the Mevlana Museum in Konya with a similar but more finely worked pattern and dated it to the 17th century. She connects this carpet with the Caucasian "dragon carpets" and interprets the carpet patterns in the pictures of van Eyck and Petrus Christ as an early Anatolian forerunner of this later Caucasian pattern design.

The main borders of the carpets in the pictures of the “Paele” and “Lucca Madonna” as well as in “Virgin with Child and Saints” each show a non-oriental, wavy three-leaf pattern. Similar ornaments can also be found in other Dutch paintings from the 15th to the early 16th centuries. The fringes of the carpets in these pictures are often on the sides rather than the top or bottom. The carpets must therefore either have had an unusual, square format or the artists took more freedom in designing the pattern and improvised using the real models. Alternatively, the carpets by van Eyck and Petrus Christ could even come from Western European production. The wavy three-leaf (clover) pattern is well known in West Gothic ornamentation.

Special carpet groups

Mamluk and Cairene Ottoman carpets

Beginning in the middle of the 15th century, a type of carpet was produced in Egypt, which is characterized by a dominant central medallion, or 3–5 medallions lined up along the vertical axis of the field. Numerous smaller ornaments, such as eight-pointed stars or smaller floral patterns, are arranged around these medallions. In Wilhelm von Bode's words, the innumerable small, densely arranged ornaments give the impression of looking through a kaleidoscope . Sixty carpets of this type were presented by Venetian merchants to the English Cardinal Thomas Wolsey in return for the license to import wine into England.

The earliest known painting depicting a Mamluk carpet is Giovanni Bellini's portrait of the Doge of Venice, Loredan, and his four advisors from 1507. An unknown French master portrayed The Three Coligny Brothers in 1555 . Another depiction can be found on Ambrosius Francken's The Last Supper , around 1570. In this picture the large central medallion of the carpet is shown in such a way that it emphasizes the halo around Christ's head. The characteristic ornaments of the Mamluk carpet are clearly visible in the picture. Ydema has documented a total of 16 datable images of Mamluk carpets in Dutch Renaissance paintings.

After the conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by the Ottomans, two different cultures merged. This is also reflected in the Mamluk carpets that were knotted after the capture of Egypt. From this time on, the Cairene carpet weavers adopted traditional Turkish-Ottoman patterns. Carpets of this type were made in Egypt well into the early 17th century. A carpet of the Cairene Ottoman type is depicted in Ludovicus Finsonius painting The Annunciation . The pattern of the main and secondary borders is the same as that of a carpet that is now kept in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam . A similar carpet was illustrated by Adriaen van der Venne in Geckie met de Kous , 1630. Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghels the Elder Christ in the House of Maria and Martha , 1628, shows the same characteristic S-shaped stems ending in double sickle leaves. Different carpets of the Cairene Ottoman type are also depicted on Moretto da Brescia's frescoes in the “Sala delle Dame” in the Palazzo Salvadego in Brescia, Italy.

Ambrosius Francken - The Last Supper, 16th century, Royal Museum of Fine Arts (Antwerp) , with an Egyptian Mamluk carpet in the background

Louis Finson , The Annunciation. 17th century, Museo del Prado , depicting an Ottoman carpet from Cairo

Jan Brueghel and Peter Paul Rubens , Christ in the House of Marthas and Mary , 1628, National Gallery of Ireland , depicting an Ottoman carpet from Cairo.

Cairen Ottoman carpet, 16th century Museum of Applied Arts Frankfurt St. 136

“Chessboard” or compartment carpets from the 17th century

An extremely rare group of carpets that were previously thought to be derived from the Mamluk and Kairen Ottoman carpets are the chessboard or compartment carpets. Only about thirty of these carpets are known, all of which have a similar pattern shape composed of squares, in each of the corners of which there are triangles that enclose a star pattern. The pattern made up of these squares gave the carpets their name. Their origin is still controversial. The choice of color and pattern of the carpets are similar to those of the Mamluk carpets, but they are "Z-spun" and "S-twisted", similar to the early Anatolian and Caucasian carpets. Since the early 20th century, Damascus has been assumed to be the production site for lack of more precise information . Pinner and Franses argue in this direction, since Syria used to be part of the Mamluken and later the Ottoman Empire. which could explain the similarity of patterns and colors with the Cairene carpets. The dating of the checkerboard carpets also corresponds to the registration of “Damascus” carpets in European collectors' inventories from the early 17th century. Checkerboard type carpets are also shown in Pietro Paolini's (1603–1681) self-portrait and Gabriel Metsu's picture Die Musikfreunde .

Star and medallion carpets from Uşak

In contrast to the relatively large number of preserved carpets of this type, few of them appear on Renaissance paintings.

Stern Uşak carpets are often made in large formats. As such, they represent a typical product of the more highly organized city manufacture. They are characterized by large, dark blue star-shaped primary medallions in an infinite repeat on a secondary floral tendril pattern. Their pattern was likely influenced by contemporary patterns from Northwest Persian book art. Compared to the medallion usak carpets, the concept of the infinite rapport in sternusak carpets is more consistent and is still in line with the early Turkish pattern tradition. A pattern in an infinite repeat can appear on carpets of various sizes and in a variety of dimensions, because the carpet field can reproduce any section of the pattern. Accordingly, Stern-Uşak carpets are available in many different formats.

Medallion usak carpets usually have a red or blue field, which is decorated with a floral grid or leaf tendrils, as well as oval primary medallions, which alternate with smaller eight-fold lobed stars, or lobed medallions, which are bound in interlaced floral patterns. Their borders often have palmettes on a floral or leaf band and "pseudo-kufic" signs. The most famous depiction of a medallion Uşak carpet, At the matchmaker was painted in 1656 by Jan Vermeer . The carpet is placed horizontally; the upper or lower end with the star-shaped corner medallion lies under the hand of the woman who is holding the glass. The carpets in Vermeer's pictures The music lesson , girl reading a letter at the open window and Das Konzert are so similar to each other down to the details of the pattern and the texture of the fabric that all three perhaps go back to a single carpet owned by Vermeer. The paintings by Vermeer, Steen and Verkolje also show a special type of Uşak carpet, of which no surviving copy is known. These carpets are characterized by their rather dark colors, the coarse weave, and rather degenerate curvilinear patterns. It is believed that the Ottoman factories produced them specifically to meet the increased demand.

Paris Bordone , The Fisherman's Ring , 1534. The only known image of a large star usak with eight-pointed star medallions.

Jan Vermeer , Lady at the Virginal with a Gentleman (detail), 1662–1665, Royal Collection , Buckingham Palace

Jan Vermeer , The Concert , 1663–1666, stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum , Boston in 1990 .

Jan and Nikolaas Verkolje , Portrait of Willem de Vlamingh , 1690–1700

17th century Persian, Anatolian and Indian carpets

|

|

|

|

Left picture : Pieter de Hooch , portrait of a family making music , 1663, Cleveland Museum of Art

Right picture : Carpet of the “ Transylvania type ” 17th century, National Museum Warsaw |

||

During the 16th and 17th centuries, carpets remained an important decorative element, for example in the English portraits of William Larkin . The finely knotted silk carpets from the time of Shah Abbas I from Kashan and Isfahan are rarely depicted in paintings, because they were undoubtedly rarely found in European homes. A lady playing the theorbo by Gerard Terborch , ( Metropolitan Museum of Art , Inv. 14.40.617) represents such a carpet. It lies on the table on which the lady's gentleman is sitting. On the other hand, floral “Isfahan” carpets were exported in large numbers to Portugal, Spain and the Netherlands, and are often depicted in pictures by Velásquez, Rubens, Van Dyck, Vermeer, Terborch, de Hooch, Bol and Metsu. Again, the known dates of creation of the pictures provide fixed points for establishing a chronology of carpet production.

Anthony van Dyck's royal and aristocratic clients had mostly already switched to being portrayed with Persian carpets . Less wealthy are still shown with Turkish carpets. The portrait of Abraham Graphaeus by Cornelis de Vos , made in 1620 , and Thomas de Keyser's Portrait of a Man (1626) and Portrait of Constantijn Huyghens and his Secretary (1627) are among the earliest pictures showing a new Anatolian type of carpet, which was then in large Quantities reached Europe. The Ottoman manufacturers reacted to the increasing European demand for knotted carpets. A number of these carpets have survived in Transylvania, which was an important trading post between the Ottoman Empire and Europe during the 15th to 17th centuries. Carpets of this type are commonly referred to as Transylvanian carpets (Ydema 1991, pp. 48-51). Pieter de Hooch's Portrait of a Family Making Music (1663) shows such a “Transylvanian Carpet”. In what was then the American colonies in 1741, Robert Feke painted Isaac Royall and his family seated around a table with a Bergama rug on it.

From the middle of the 16th century onwards, direct trade with the Mughal Empire brought Indian carpets, influenced by Persian models, to Europe. Dutch painters of the Golden Age , such as Jan Vermeer in his music class , demonstrated their skill in realistically reproducing the lighting effects on spread out carpets. In his day these carpets were quite common in wealthy households, as historical wills and estate inventories show.

By the end of the 16th century, Islamic carpets had lost much of their status as objects of prestige. The highest-ranking people portrayed were now more likely to be depicted with precious carpets from European manufacturers such as the French Savonnerie manufactory . On the one hand, their simpler patterns were easier to depict, and on the other hand, the interest in detailed, realistic depiction in the visual arts of that time was disappearing. If oriental carpets were depicted in detail, it was more likely in explicit orientalist pictures of later European painting.

William Larkin , Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset , 1613, is on a "lottery carpet".

Portrait of Abraham Grapheus , Cornelis de Vos, 1620, Royal Museum of Fine Arts (Antwerp) , 104

Thomas de Keyser, Portrait of Constantijn Huygens and his Secretary , 1627, National Gallery (London)

Nicolas Tournier , concert , 1630–1635.

Anthony van Dyck , Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke with his family , representation of a Persian carpet

Gabriel Metsu , Man, Writing a Letter , 1664–1666, National Gallery of Ireland

Islamic carpets in the cultural context of the Renaissance period

The European perception of Islamic carpets during the Renaissance period is characterized by three aspects:

- Due to their rarity, preciousness and strangeness, oriental carpets were often used as a background for depicting saints and religious scenes, especially in the early Renaissance period.

- In a more general sense, Islamic carpets were perceived as rare commodities and representative luxury objects. From the mid-sixteenth century onwards, the iconological context tended more towards the idea of debauchery and vanity or " vanitas ".

- As the contacts between the Islamic world and Europe became closer, often accompanied by violence, Islamic carpets were often used symbolically for the foreign world and culture of Islam and then served for Christian self-affirmation.

In any case, according to current theories in Europe, Islamic carpets were consistently understood differently than in their original cultural context, which was never fully understood during the Renaissance period.

Sacred pictorial themes

The first oriental carpets appear on paintings from the early Renaissance period. In most cases they serve as a backdrop for religious scenes; Saints are depicted enthroned or standing on carpets and thus separated and emphasized from their surroundings. Ordinary people, often the creators of the paintings, were sometimes allowed to partake of the atmosphere of holiness by being depicted close to the holy person, or literally standing or kneeling “on the same carpet”. This context is still understood and sometimes used today. Religious iconography was later adopted by politically influential people to emphasize their social status and power.

In 1998, Volkmar Gantzhorn presented an alternative interpretation of the representation of oriental carpets in Renaissance painting, especially in connection with sacred pictorial themes. After comparing the patterns and symbols of the carpets depicted and preserved, for example with the Armenian book illumination of the same period, he comes to the conclusion that the majority of the carpets preserved and reproduced in the paintings were made by Christian Armenians , and that they were symbolically coded because of them sacred meaning as "Christian oriental carpets" were used in the churches of Western Europe. Gantzhorn justifies the lack of written sources that would support this hypothesis from a contemporary Western European point of view with the predominantly oral tradition, which is only fully accessible to a religious elite, in the knotting of hidden symbols of Armenian Christians, and the breakdown of this tradition as a result of the expulsion of the Armenians from Anatolia in the early 20th century. The discussion, which was sometimes polemical and not always factual against the background of the Armenian genocide , has not yet been concluded.

Luxury objects and decoration

We don't understand exactly what the Renaissance artists thought of the carpets they depicted. We know that on special occasions St. Mark's Square was adorned with carpets that hung from the window sills of the surrounding palaces and houses. The carpets act as a decorative framework, emphasizing the important plot depicted in the picture. Similar to the inaccurate pseudo-Kufic writing on other paintings of the time, European artists borrowed motifs from a foreign culture that they basically did not understand.

In a series of letters from Venice, written between August 18 and October 13, 1506, Albrecht Dürer reports to his friend and supporter Willibald Pirckheimer about the difficulties in acquiring two carpets for him:

" Vnd dy 2 tebich wants to help me, Anthoni Kolb awff daz hubschpt, preytest and wolfeillest khawffen. So I have, I want to give the boy Im Hoff, so that he can always go to sleep. Awch I want to see the feathers of the crane.

(18. August 1506)

In all work I am kertt with the tewichs, but I can´t kumen preiten. Sy are al narrow and long. But I still have old research thorn, awch Anthoni Kolb.(September 8th, 1506)

I ordered two dewich, dy would tzalen tomorrow. But I have sy nit wolfell kunen kawffen.(October 13, 1506) "

During his stay in Venice, Dürer acquired various luxury goods on behalf of Pirckheimer and considers carpets to be like gold, jewels or ostrich feathers. It is not known whether Dürer attributed a special artistic value to the carpets. He never depicted oriental carpets.

A very common type of genre painting of the Dutch Golden Age and the Flemish Baroque is the so-called “happy society”. These pictures show a group of people enjoying themselves, who are usually shown sitting and drinking, often singing and making music. Oriental rugs often serve as tablecloths and table decorations, or are spread out over pieces of furniture. As decoration, they either underline the wealth and modesty of the portrayed, or create a context of exoticism and debauchery to brothel or feast scenes, as in Jan Vermeer's painting At the Coupler . From the 16th century, depictions of oriental carpets can be found on still lifes . Various valuable and exotic objects such as Chinese porcelain vessels, animals such as parrots or tarantulas are depicted on them. Often these objects have an allegorical meaning or symbolize “vanitas” , the futility of human effort. The allusion to futility is illustrated by the inclusion of symbols such as the human skull, or inscriptions on the paintings that represent the biblical text from Ecclesiastes 1: 2; Quote 12: 8. As early as 1533, Hans Holbein the Younger had depicted an anamorphosis of a human skull in his picture The Ambassadors . Regardless of their allegorical meaning, the objects in still lifes were often arranged on precious velvet fabrics, marble table tops or oriental carpets. In this context, the focus is almost exclusively on the material and decorative value of the objects depicted and their allegorical meaning.

Objects of European self-assurance

In September 1479, the Venetian painter Gentile Bellini was sent by the Senate of Venice as cultural ambassador to the court of Sultan Mehmed II in his new capital, Constantinople , in order to promote peace negotiations between Venice and the Ottoman Empire . Giorgio Vasari wrote that Bellini "painted the Emperor Mahomet so lifelike that it was viewed as a miracle." Bellini's dating and authorship of the portrait have been questioned, but Bellini is the first great Renaissance painter to actually run the court of an Islamic sultan. The influence his encounter with the Islamic world had is reflected in the orientalist motifs that appear in several of Bellini's paintings. St. Mark's Preaching in Alexandria from 1507 shows in an anachronistic way the patron saint of Venice preaching to Muslims. The architecture in the background consists of a disjointed collection of buildings that stylistically do not match the Islamic architecture of the time. The stage-like background for the sermon of St. Mark is decorated with a camel and a giraffe as well as architectural elements such as an Egyptian obelisk. Bellini's use of these decorative elements is reminiscent of the way in which oriental carpets are depicted in the paintings of the 14th and 15th centuries: They are representations of the exotic and precious, they set the stage for an important person or action, but do not show any Knowledge of the original cultural context.

The image of King Edward VI. von England from 1547 on an oriental carpet, in front of a throne placed on the same carpet, emphasizes the strength and power of the young Fidei defensor by means of a deliberate reference to the pose of his father in his painting by Hans Holbein.

We do not know how much Ambrosius Francken knew about the cultural background of the Mamluk carpet, which he used as the background for his Last Supper . The picture can only be roughly assigned to the 16th century. The use of the central medallion of an oriental carpet to emphasize the halo of Christ, however, represents a special case: the motif could either have been used because of the coincidental similarity of the two image patterns, but could also intentionally serve to reinforce the predominance of Christianity in the Renaissance period. At that time, the Europeans had every reason to fear the Islamic world: in 1529, Sultan Suleyman I , “the Magnificent”, besieged the city of Vienna for the first time. The Ottoman Empire remained a constant threat to Western Europe until the late 17th century.

Pinturicchio (1502–1509) paints on the eighth picture of his fresco cycle in the Piccolomini library of the Duomo of Siena Pope Pius II , as he convened a prince's day in Mantua in 1459 to plan a new crusade . A table in front of the Pope's throne is covered with an oriental carpet. It is believed that the carpet could be a trophy from previous campaigns.

Precious oriental carpets were part of the so-called “ Turkish booty ” from the siege of Vienna , which was finally repulsed on September 12, 1683. The new Christian owners proudly reported in letters of their looting. There are still carpets preserved that contain inscriptions with the name of the new owner and the date they were taken into possession:

" AD Wilkonski XII septembris 1683 z pod Wiednia

" AD Wilkonski, 12 September 1683, Vienna ""

In the centuries-long cultural exchange between Europe and the Islamic world, which led to intensive mutual influence in many areas, the oriental knotted carpet remained an exotic foreign body in European culture. It was left to a later century to seek a better understanding of the role of carpets in the context of Islamic culture. While Islamic carpets originally served to decorate Renaissance paintings, the pictures in turn contributed to a deeper understanding of the history and culture of the oriental carpet and thus the history of Islamic art. Comparative art-historical research on oriental carpets in Renaissance paintings adds further facets to the highly complex and sometimes ambivalent image of the Ottomans during the Western European Renaissance period.

Gentile Bellini , St. Mark preaching in Alexandria , ca.1507

Hans Holbein the Younger and workshop, Heinrich VIII. Stands on a "Stern-Uşak" carpet, approx. 1530.

Edward VI. on a "Holbein" carpet, c.1547.

Ambrosius Francken , The Last Supper , 16th century, Royal Museum of Fine Arts (Antwerp) , with an Egyptian mamluk carpet

In 1459 Pinturicchio , Pius II convenes a prince's assembly in Mantua to discuss a new crusade . Fresco in Siena Cathedral , Piccolomini Library, 1502–9.

Carlo Caliari , Shah Abbas I embassy to Venice, 1595. Fresco in the Doge's Palace , Venice

literature

- Wilhelm Bode, Ernst Kühnel: Near Eastern knotted carpets from ancient times . 5th edition. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-7814-0247-9 .

- Gordon Campbell (Ed.): The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts . tape 1 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 978-0-19-518948-3 , pp. 187–193 , Carpet, § 2 History, 3. Islamic World (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Rosamond E. Mack: Bazaar to Piazza. Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600 . University of California Press, 2001, ISBN 0-520-22131-1 (English).

- Donald King, David Sylvester (Ed.): The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, From the 15th to the 17th century . Arts Council of Great Britain, London 1983, ISBN 0-7287-0362-9 (English).

- Onno Ydema: Carpets and their datings in Netherlandish Paintings, 1540-1700 . Antique Collectors' Club, Woodbridge 1991, ISBN 1-85149-151-1 (English).

- Luca Emilio Brancati: Figurative Evidence for the Philadelphia Blue-Ground SPH and an Art Historical Case Study: Gaudenzio Ferrari and Sperindio Cagnoli . In: Murray Lee Eiland, Robert Pinner (Eds.): Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies . tape 5 , Part 1. International Conference on Oriental Carpets, London / Danville (California) 1999, ISBN 1-889666-04-1 , pp. 23-29 (English).

- John Mills: Carpets in Pictures . The National Gallery, London 1976 (English, revised and expanded edition published as Carpets in Paintings , 1983).

- John Mills: Early animal carpets in western paintings - a review . In: Hali. The International Journal of Oriental Carpets and Textiles . tape 1 , no. 3 , 1978, ISSN 0142-0798 , p. 234-243 (English).

- John Mills: Small-pattern Holbein carpets in western paintings . In: HALI . tape 1 , no. 4 , 1978, p. 326-334 (English).

- John Mills: Three further examples . In: HALI . tape 3 , no. 3 , 1981, p. 217 (English).

- John Mills: "Lotto" carpets in western paintings . In: HALI . tape 3 , no. 4 , 1981, p. 278-289 (English).

- John Mills: East Mediterranean carpets in western paintings . In: HALI . tape 4 , no. 1 , 1981, p. 53-55 (English).

- John Mills: Near Eastern Carpets in Italian Paintings . In: Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies . tape 2 , 1986, ISBN 0-948674-02-4 , pp. 109-121 (English).

- John Mills: The 'Bellini', 'Keyhole', or 'Re-entrant' rugs . In: HALI . No. 58 , 1991, pp. 86-103, 127-128 (English).

- John Mills: The animal rugs revisited . In: Murray Lee Eiland, Robert Pinner (Eds.): Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies . tape 6 . International Conference on Oriental Carpets, London / Danville (California) 2001, ISBN 1-889666-07-6 , pp. 46-51 (English).

- Valentina Rocella: Large-Pattern Holbein Carpets in Italian Paintings . In: Murray Lee Eiland, Robert Pinner (Eds.): Oriental Carpet and Textile Studies . tape 6 . International Conference on Oriental Carpets, London / Danville (California) 2001, ISBN 1-889666-07-6 , pp. 68-73 (English).

- Robert Born et al .: The Sultan's world. The Ottoman Orient in Renaissance art . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2015, ISBN 978-3-7757-3966-5 (English, exhibition catalog Brussels and Krakow).

Web links

- Flickr carpet Index: The Oriental Carpet in Early Renaissance Paintings (English)

- Carpets in Western Europe during the Renaissance (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Kurt Erdmann: Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpet . Busse, Herford 1966.

- ↑ Carol Bier: From grid to projected grid: Oriental carpets and the development of linear perspective. . In: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America - 12th Biennal Symposium . 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ Leon Battista Alberti, Rocco Sinisgalli (ed.): On painting: A new translation and critical edition . 1st edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2011, ISBN 978-1-107-00062-9 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e David Carrier: A world art history and its objects . Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, Pa. 2008, ISBN 978-0-271-03415-7 .

- ↑ Julius Lessing: Ancient oriental carpet patterns. After pictures and originals of the XV. - XVI. Century . Berlin 1877.

- ↑ Kurt R. Pinner: Foreword to The History of the Early Turkish Carpet by K. Erdmann, London 1977, ISBN 978-0-905820-02-6 (new edition of the German / Turkish edition 1957).

- ^ Walter B. Denny: How to read Islamic carpets , 1st edition, Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2014, ISBN 978-1-58839-540-5 .

- ^ Mack, p. 75.

- ^ Mack, p. 75

- ^ King & Sylvester, p. 49

- ↑ Mack 2002, p. 74

- ^ William Marsden, Thomas Wright (eds.): Travels of Marco Polo, the Venetian: the translation of Marsden revised . Bibliobazaar, Llc, [Sl] 2010, ISBN 978-1-142-12626-1 , p. 28 (English).

- ^ King & Sylvester, p. 17

- ↑ Mack 2002, pp. 74-75.

- ↑ Mack, p. 75; King & Sylvester, pp. 13 and 49–50

- ↑ King and Sylvester, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ King and Sylvester, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Animal carpet in the Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ National Gallery London . Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ↑ Mack, p. 67

- ↑ Mack, p. 76

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 14

- ↑ Mack, p. 77

- ↑ Mack, pp. 73-93.

- ↑ Mack, p. 84

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 58

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 20

- ↑ King and Sylvester, pp. 14-16, 56, 58.

- ^ King & Sylvester, p. 78

- ↑ King & Sylvester, pp. 14, 26, 57-58

- ↑ Campbell, p. 189. National Gallery zoomable image ( Memento of the original dated May 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ King and Sylvester, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Todd Richardson: Plague, Weather, and Wool. AuthorHouse, 2009, p. 182 (344), ISBN 1-4389-5187-6 .

- ↑ Erdmann, 1966, pp. 130-136

- ↑ King & Sylvester, pp. 26-27, 52-57

- ^ Campbell, p. 189.

- ^ Wilhelm von Bode, Ernst Kühnel: Vorderasiatische Knüpfteppiche from old times , 5th edition, Klinkhardt & Biermann, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-7814-0247-9 .

- ↑ Bode / Kühnel, 1985, pp. 29-30.

- ↑ Kurt Erdmann: The oriental knotted carpet . 3. Edition. Ernst Wasmuth, Tübingen 1955, p. 26 .

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 67

- ^ Charles Grant Ellis: The "Lotto" pattern as a fashion in carpets , 1st edition, Hauswedell, Hamburg 1975, pp. 19–31.

- ^ Friedrich Spuhler: Carpets from Islamic Lands , 1st edition, Thames & Hudson, London 2012, ISBN 978-0-500-97043-0 , p. 44.

- ↑ Amy Briggs: Timurid Carpets; I. Geometric carpets . In: Ars Islamica . 7, 1940, pp. 20-54.

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 67

- ^ Stefano Ionescu: Transylvanian Tale . HALI 137, 53. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ↑ Serare Yetkin: Historical Turkish Carpets . 1st edition. Turkiye is Bankasi Cultural Publications, Istanbul 1981, p. 59-65 (English).

- ↑ Ghirlandaio rug, 17th century, sold at Christie's April 5, 2011 .

- ^ Ian Thompson: Centralized Designs . In: Eberhart Herrmann (ed.): From Konya to Kokand - rare oriental carpets . tape 3 . Eberhart Herrmann, Munich 1982, p. 39 .

- ^ Walter B. Denny: How to Read Islamic Carpets . 1st edition. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-58839-540-5 , pp. 27 (English).

- ^ Ghirlandaio carpet, 19th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Kurt Zipper, Claudia Fritzsche: Oriental Rugs . 1st edition. Vol. 4 - Turkish. Antique Collectors' Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK 1995, p. 18 (English).

- ^ Ian Thompson: Centralized Designs . In: Eberhart Herrmann (ed.): From Konya to Kokand - rare oriental carpets . tape 3 . Eberhart Herrmann, Munich 1982.

- ↑ Werner Brüggemann, Harald Boehmer: Carpets of the farmers and nomads in Anatolia . 1st edition. Verlag Kunst und Antiquitäten, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-921811-20-1 , p. 60-78 .

- ^ King and Sylvester, p. 20

- ↑ Werner Brüggemann: Der Orientteppich , 1st edition, Dr Ludwig Reichert Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89500-563-3 , pp. 87-176.

- ^ Yetkin, 1981, plate 47

- ^ Yetkin, 1981, p. 71

- ↑ Ydema, 1991, p. 9

- ↑ Ydema, 1991, p. 9

- ↑ a b Onno Ydema: Carpets and their datings in Netherlandish paintings: 1540-1700 . Antique Collectors' Club, Woodbridge 1991, ISBN 1-85149-151-1 , p. 9.

- ^ May H. Beattie: The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection of Oriental Rugs , 1st edition, The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Castagnola 1972.

- ↑ Ydema 1991, pp. 19-21

- ↑ Cairene Ottoman Carpet in the Met. Museum of Art . Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ R. Pinner, M. Franses: East Mediterranean carpets in the Victoria and Albert Museum. In: Hali 1981 IV / 1, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Ydema 1991, pp. 21-25

- ↑ The Sala delle Dame . In: Hali . No. 200 , 2019, pp. 208 (English).

- ^ R. Pinner, M. Franses: East Mediterranean carpets in the Victoria and Albert Museum. In: Hali. Volume 4, No. 1, 1981, p. 40.

- ↑ Ydema 1991, p. 43

- ^ Stern-Uşak, Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ↑ [sn]: Tapis - Present de l'orient a l'occident . 1st edition. L'Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris 1989, ISBN 978-2-906062-28-3 , pp. 4 (French).

- ^ Medallion-Uşak, Metropolitan Museum of Art . Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- ↑ Ydema 1991, pp. 39-45

- ^ King & Sylvester, p. 19

- ↑ In the 19th century, carpets of this type from Polish noble houses led to carpets of this type being referred to as "Polonaise" carpets. Kurt Erdmann suggested the more appropriate name “Shah Abbas” carpets.

- ↑ Maurice Dimand, Jean Mailey: . Oriental Rugs in The Metropolitan Museum of Art page 60, fig 83rd

- ↑ Dimand and Mailey 1973, p. 67: Herat floral carpets shown in A visit to the children's room by Gabriel Metsu (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 17.190.20), p. 67, fig. 94; Portrait of the Omer Talon , by Philippe de Champaigne , 1649 ( National Gallery of Art , p. 70, fig. 98); Woman with a water jug , by Jan Vermeer (Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 89.15.21), p. 71, fig. 101

- ↑ Stefano Ionescu: Antique Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania , 1st edition, Verduci Editore, Rome 2005 (accessed September 7, 2015).

- ↑ Ydema 1991, p. 51

- ^ Collection of Harvard University Law School; in Dimand and Mailey 1973, p. 193, fig. 178.

- ^ King and Sylvester, pp. 22-23.

- ^ The coffin of Pope John Paul II on a Bijar carpet, 2005 . Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Volkmar Gantzhorn: Oriental carpets . Benedikt Taschen, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-8228-0397-9 .

- ↑ a b Hans Rupprich (Ed.): A. Dürer. Written estate . 3. Edition. German Association for Art History, Berlin 1956.

- ↑ Kurt Erdmann: Europe and the Orient Carpet . 1st edition. Florian Kupferberg Verlag, Mainz 1962, p. 49 .

- ^ Julian Raby: Venice, Dürer, and the oriental mode , 1st edition, Islamic Art Publications, [Sl] 1982, ISBN 978-0-85667-162-3 .

- ↑ Mariët Westermann: A worldly art: the Dutch Republic, 1585-1718 , 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT 2007, ISBN 978-0-300-10723-4 .

- ^ Ingvar Bergström: Dutch still-life painting in the seventeenth century , Facsim. Edition, Hacker art books, New York 1983, ISBN 978-0-87817-279-5 .

- ^ Artists of the Renaissance - descriptions of the lives of excellent Italian builders, painters and sculptors - , with a foreword by Ernst Jaffé based on the translation by Schorn and Förster, Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-86820-076-8 .

- ↑ The Sultan Mehmet II . Nationalgallery.org.uk. Archived from the original on August 26, 2007. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Robert Born, Michael Dziewulski, Guido Messling (eds.): The Sultan's world: The Ottoman Orient in Renaissance art . 1st edition. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2015, ISBN 978-3-7757-3966-5 (English).

- ↑ Kurt Erdmann: The oriental knotted carpet: attempt to represent its history. Ernst Wasmuth Publishing House, Tübingen 1955.