Darfur conflict

The conflict in Darfur has been an armed conflict between the various ethnic groups in Darfur and the Sudanese government in Khartoum that has been going on since 2003 . Rebel movements that have emerged from black African tribes are demanding more participation in the state and the development of their region. The government military action against the rebels and support in this fight local militias of Arab consist rider nomads and called Janjaweed (Arabic jinn "spirit, demon"; Jawad "horse") have become known.

Around 200,000 people died in the conflict by 2007. A UN estimate assumes 300,000 deaths in early 2008. According to an uncertain estimate, this number had doubled by 2016. An estimated 2.66 million were displaced within the Darfur region in December 2015. They are known as IDP ( "Internally displaced persons" ). The Janjawid and Sudanese government forces committed serious human rights violations. These include the destruction of villages, massacres of civilians and rape. Amnesty International also holds Sudanese government units responsible for the use of chemical warfare agents in 2016.

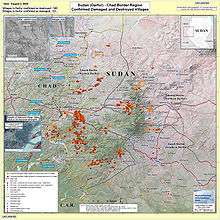

The conflict has spread to the border areas of Chad and several thousand Darfuris have fled to the Central African Republic . Since 2007, UNAMID, one of the world's largest UN peace missions, has been stationed in Darfur. In October 2009, 19,000 of the 26,000 police officers and soldiers to be deployed for the mission were on site. Blocking measures by the Sudanese government, bureaucratic hurdles and problems with the cooperation between the units have made the mission considerably more difficult.

Background and history

The Darfur region is inhabited by different peoples who can be divided into three groups according to their origin: Black African ethnic groups such as the eponymous Fur , who make up almost a third of the population of Darfur and settle around the central Jebel Marra , Masalit in the west and Zaghawa in the north of the area, and Arab tribes that invaded today's Sudan since the 13th century and, if they have become cattle nomads, are grouped under the name Baggara . In between there are small ethnic groups in all parts of Darfur, such as the Berti , who immigrated from the Sahel , were Arabized through cultural adoption in the last centuries and can also be assigned to the Baggara with a nomadic way of life. There are over 30 large and small ethnic groups (Arabic qabail ), the majority of which are black Africans and belong to the Nilo-Saharan language family . The terms “black African” and “Arabic” are therefore less to be understood as an ethnic distinction than as socially constructed identities; In addition, the ethnic designation " Arab " is limited to a common saga of origin and other cultural characteristics. Camel nomads and cattle herders, regardless of their origin, tend to identify as Arabs. According to the way of life, Baggara - cattle nomads , Aballa - camel nomads , Zurga - farmers and the city dwellers can be distinguished.

All ethnic groups are Sunni Muslims, with a large number of followers of the Tijaniya fraternity. From 1650 until the British annexation in 1917, Dar Fur (Arabic for "House of Fur") was an independent sultanate. Until the end of the 18th century, the ruling empire was ideologically restricted to the Fur ethnic group, after which a cross-national state administration was established. As can be seen from a decree of the last Sultan Ali Dinar (ruled 1898–1916) to his chiefs, questions of land and water rights were regulated centrally and with foresight. Up to this time, Fur and Masalit lived in hierarchically structured states, whose bureaucratic apparatus only collapsed during the Mahdi rule , whereas the nomadic Arabs lived in loose tribal associations. Until the independence of Sudan in 1956 and afterwards, hardly any efforts were made to develop the marginalized region economically. During the British colonial era , the only income in the region came from Darfuris who emigrated and found work in the cotton plantations of the Gezira plain . Only the construction of a railway from Khartoum to Nyala in 1959 brought a certain boost to the south.

One reason for earlier conflicts was the geographical location of Darfur as a center for the slave trade , through which the slave traders of the Fur and Arab traders, together and in competition with one another in the Bahr al-Ghazal region, obtained slaves from small black African empires such as Dar Fertit . Occasionally there were clashes between Fur and Baggara, especially with the powerful Rizeigat in southeast Darfur. Still existing old reasons for conflict are disputes between arable farmers and nomadic cattle breeders over water and pasture land, whereby conversely to the common classification there are also arable farmers, who are assigned to the Arab population, and black African nomads. There have been times of peaceful cooperation in history between sedentary and nomadic groups and unrest at other times. Violent quarrels used to be fought with spears and settled through the mediation of the elders. The disputes intensified due to the scarcity of resources caused by two major periods of drought in the early 1970s and mid-1980s. In addition, there was a population increase from 1.3 million people in 1973 to 3.5 million by 1983.

The description of the conflicts along ethnic dividing lines, which may have made sense in earlier times, is still somewhat justified and provides a rough framework, but is not sufficient for understanding societies that are partially segmented down to the clan level. Conflicts are historical processes; their causes can change. The reduction of the conflict as a war between Arabs loyal to the government and rebellious black Africans, as conveyed in the western media, is not enough.

Ethnic conflict as a cause

The massacre of El Diein , a trading town on the railway line between Babanusa and Nyala , in March 1987 , shows that the clashes between the Arab and black African peoples, which are usually explained in the above-mentioned ethnic context, are not a thing of the past In the south of Darfur, the dominant Arab ranchers, the Rizeigat, lived together with Fur, Dinka , Zaghawa and others in an unstable equilibrium. After the civil war in South Sudan began in 1983, more and more dinka, farmers and shepherds, fled the south to El Diein. In May 1986 there were already around 17,000 Dinka in the city. There were quarrels at the water points. On March 27, 1987, the city's population attacked the newcomers. Civilians attacked other civilians with sticks and spears. After the first deaths on the part of the Dinka, some of them allowed themselves to be persuaded by the police to take the train to Nyala the next day to safety. The train did not leave. Several hundred penned Dinka in seven wagons were smothered in the smoke by a mob with burning tufts of grass in the wagons or killed while trying to escape, other Dinka who had fled to the police yard suffered the same fate there. Amnesty International later confirmed 426 Dinka killed. Similar massacres took place in other cities between 1987 and 1989.

Economic and ecological causes

In 2007, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon identified the effects of climate change as a cause of the crisis in Darfur. He has not been criticized for pointing out possible ecological causes of the conflict, but because such a statement relieves the local population of their responsibility for their own environment, but above all because the political dimension is disregarded. The other view, shared by Western governments, focuses on the political oppression, economic neglect and militarization of the region by the Sudanese government. Eric Reeves, who argues politically, considers Ban Ki-moon's statement to be a misjudgment, which led to the UN Security Council being too hesitant to participate in negotiations.

The development since the 1980s is understood as the medium-term prehistory. Since that time, a decline in cultivated areas and pastureland has been observed due to increasing desertification and soil erosion , which forced the affected ethnic groups to different degrees to migrate from the dry savannah areas in the north to the more rainy south of Darfur. As the country was already populated everywhere, conflicts arose. The Zaghawa were mostly more successful in the violent land grabbing in the 1980s than the Meidob or Berti, who moved south a little later. In particular, as a result of the drought years 1983/84, the geographical breakdown according to economic types was confused by the southern migrations. Camel nomads in North Darfur, arable farmers in the central region around the Jebel Marra and cattle breeders in the south all claimed foreign land in the dry season. Data show a correlation between the increase in local conflicts and decreasing annual rainfall. With this statement, Mohamed Suliman sees the conflict, which began as a violent ethnic conflict in 1953, as one of the main economic and ecological causes today. A study carried out at Santa Clara University in California based on the precipitation data, however, comes to the conclusion that the fluctuating amounts of precipitation, which do not follow a clear trend, correlate only loosely with the intensity of the violent conflicts since 2003.

Turnaround in power politics and militarization

In the drought period of 1972–1974, conflicts were still rare, localized and manageable; it was different from the mid-1980s, when smaller skirmishes gradually expanded and left civil war-like devastation, with entire villages being burned down and looted. At the center of most machine gun conflicts at the end of the 1980s were the Zaghawa, who are also disproportionately represented in the various rebel groups of today.

The second phase, or militarization of the conflict, was considered to be the years 1987 to 1993, in which 27 Arab tribes formed an alliance whose fighters, Janjawid, aimed to conquer the Fur, or, more precisely, the Fur land on Jebel Marra . By the time of the peace conference in 1989, over 5000 fur and 400 Arabs are said to have been killed. The ecological cause with economic effects had turned into a struggle for regional supremacy. Neither the fatalities nor the tens of thousands of displaced persons were noticed internationally. The right of disposal over pastureland is one of the most important power and economic factors in Darfur. From the early to mid-1980s, the proportion of cattle exported from the Darfur region increased from a quarter to half of total export revenue.

During the reign of Sadiq al-Mahdi (1986–1989), the decision was made to supply the Arab nomads ( Baggara ) with weapons, supposedly in order to defend themselves against attacks by the South Sudanese SPLA . Unsurprisingly, the Arab militias used their weapons against the black African population of Darfur. The conflict took on an openly racist dimension.

For reasons of power politics, Darfur was divided into the three provinces of North , South and West Darfur in 1994 . The majority of provincial governors have come from within the government since then. Since independence, all heads of government in Khartoum have come from the northern region of Sudan, although this only makes up a small proportion of the total population. The uprising is thus directed against marginalization and against the economic monopoly of the centralist government. The main point of controversy in economic terms is the growing income from oil production since 1999. With the beginning of the peace talks to settle the civil war in South Sudan , the non-Arab Darfuris felt completely marginalized and the rebel organization JEM , founded in 2001, carried out the first attack in February 2003.

International dimension

Chad

The President of Chad Idriss Déby came to power by force in 1990 with Sudanese support. He had prepared his coup militarily from Darfur. In the first attacks by the Darfur rebels in 2003, which were carried out by Zaghawa, his own ethnic group, he initially stood as an ally behind the Sudanese government. In March 2003, Déby sent troops to combat the JEM and SLA, which were using Chad as a retreat, inside Darfur. (For the rebel groups, see the next section.) The Zaghawa troops refused to fight their own ethnic group and warned the insurgents of their arrival. The Zaghawa rebelled within the army and the generals changed. Subsequently, Déby supported splinter groups who had fallen away from the JEM and were acting against the JEM. From 2004, Sudan tried to unite opponents of the government in Chad. In return, Déby began to support Sudanese rebels such as the JEM and the SLA / M in 2005, and since then Sudan has been arming the rebels of the FUC ( Front uni pour le changement, “United Front for Change”) in Chad. The proxy war between the two countries escalated into a direct confrontation in late January 2008 when Chadian rebels and Sudanese units advanced to the government seat in N'Djamena . Déby's troops were able to repel the attackers with the support of the Sudanese JEM.

Libya

Muammar al-Gaddafi participated in the Chadian civil war in the 1970s as an opponent of the rebel leader Hissène Habré , who was supported by France and the United States . Habré's base of operations in the fight against the government of President François Tombalbaye was - with the tolerance of the then Sudanese President Numeiri - Darfur. There Habré received arms deliveries, with the help of which the Libyan units could be defeated and driven out of the country in 1981. Habré became president of Chad and served from 1982 to 1990. Sudan and Libya had become opponents since Numairi came to power. After Numairi's dismissal in 1985, relations between the two countries improved. In Chad, Libya continued to fight the Habré government. 1987–1988 a war broke out over a border strip , in which Libyan troops were able to use the west of Sudan to invade Chad. It was in return for Libyan support in the war against South Sudan. During this time Darfur was flooded with Libyan arms at the lowest prices. Chadian militias were equipped by Libya to support the Janjawid in Darfur.

With the Libyan presence in Darfur, Gaddafi was pursuing another goal after his withdrawal from Chad. Since he came to power, he has championed a pan-Arab idea emanating from his country , which he now sought to spread in Darfur. A militant Arab organization of around 2,000 men called Al tajammu al-arabi ("Arab Assembly") was sent to Darfur in 1987, where it was supposed to spread the ideology of Arab supremacy among the equestrian militias. The ideological arming of the Janjawid for later struggle dates from this time.

An explanation for the dominance of the equestrian militias going back to the 1970s focuses on Ahmat Acyl Aghbash, who died in 1982, the commander of a Libyan “Islamic Legion” that operated in Chad and a Chadian militia called “Volcano Brigade”. The mission target chosen by Gaddafi for the violent and religious struggle was a clan of the Rizeigat camel nomads under the old leader Sheikh Hilal. Ahmat Acyl convinced the Rizeigat with the idea of a direct descent from the Koreishites , the tribe of the Prophet . Hilal's son and successor Moussa Hilal took over the fight against the Fur and organized arms deliveries from Libya in the late 1980s.

The Idriss Déby coup was also heavily supported by Libya. Through Gaddafi's declared change from Arab nationalist to peacemaker, Libya has been mediating in the Darfur conflict since 2004. The construction of an egg-shaped hotel in Khartoum, financed by Libya, is a widely visible symbol of the good economic relations . Criminal gangs move between Darfur, Chad and Libya, from where the rebels in both countries continue to take their weapons.

Main combat groups in Darfur

The situation is confusing. Since 2007, aid agencies have observed an increase in common crime.

On the government side

On the government side, army units and various militias are fighting, which are generally referred to as Janjawid . These include camel nomads (Abbala) and Rizeigat-Abbala, Beni Halba and Misirya who immigrated from Chad because of the drought in the 1980s . As Northern Rizeigat individual clans like the Shattiya, Mahamid, Eregat, Huttiya, Etetat and Jalul are summarized. Zayadia is the name of the largest group of camel nomads in the north. The majority of the Arab tribes in Darfur immigrated from the west in the mid-18th century. From the camel nomads spreading south and eastward, the cattle-raising Baggara gradually became . Paramilitary troops on the government side are the uniform-wearing Popular Defense Forces and the Border Intelligence Guards. The official armed forces are the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF). In mid-2013, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) were formed from Janjawid militias and paramilitary forces, mainly composed of Abbala-Rizeigat, other Darfuris and ethnic Nuba . They are notorious for their brutal crackdown on civilians.

The Sudanese government also used existing rivalries as an opportunity to arm non-Arab tribes and integrate them into the militia. One example is the ethnic group of the Birgit (Birgid), classified as black African , who predominantly settle in the province of South Darfur and make up the majority of the population in the city of Shearia (Sheiria). In response to Zaghawa's invasion of their territory in the 1980s, Birgit's struggle under her leader Omda Tierab against the Zaghawa-dominated SLA / M and the JEM is rated. Birgit militias, who travel with horses and camels, make up the majority of the SLA-FW and are in contact with the Sudanese government and with Arab Misseria militias. In an army-supported raid by Birgit in Shearia in January 2006, around 5,000 Zaghawa were displaced. Zaghawa took revenge the next day. Fighting between the SLA / M and the SLA-FW in North and South Darfur in early 2008 resulted in 90,000 displaced persons.

Rebel organizations

The rebel organizations that existed at the beginning of the violent conflict split off several times, some of which subsequently fought against each other. The members of these rebel troops can only be assigned imprecisely to certain ethnic groups; fighters from the same sub-group of an ethnic group can even be involved in opposing associations. The smallest rebel unit consists of a leader with loyal followers and a few pickups . The transition to criminal gangs is fluid.

- The Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA), founded in August 2001 as the Darfur Liberation Front (DLF), was the strongest political group between February 2003 and the signing of the Abuja peace agreement in May 2006. Its founder and president is Abdelwahid Mohamed al-Nur. He belongs to the Fur and lives in Paris. Members are mainly Zaghawa, Fur and Masalit.

- A group called SLA / M split off from the SLA in 2005 under the previous Secretary General Minni Arcua Minnawi . It was until Minnawi was the only one of the rebels to sign the peace agreement, the largest faction in the SLA, after which support and membership fell dramatically. Minnawi, who has officially held a position in the Sudanese government since August 2006, has hardly any supporters from his Zaghawa-Wogi ethnic group.

- In contrast, the previous SLA under its leader Abdelwahid Mohamed al-Nur received support in protest against the agreement, but this was reduced by a split.

- Groups that were equally in opposition to Abdel-Wahid and Minnawi formed an association at the end of 2006 under the name Group of 19 / SLA North Command, from whose changing alliances the SLA-Unity emerged in April 2007 . The members come mainly from Minnawi's own ethnic group, as well as from other Minnawi's opponents. It is the strongest of the SLA factions because of its good relationship with the regime in Chad and other rebel groups. The leaders are Zaghawa-Wogi.

- The Justice and Equality Movement ( Justice and Equality Movement , JEM) was founded around 1999 and began in March 2003 with the active struggle. This group is also dominated by Zaghawa-Kobe and has retreat bases around the city of Tine and the refugee camps there in the border area of Chad. Its leader until December 2011 was Khalil Ibrahim , former Minister of Education in Darfur, who had ties to Hasan at-Turabi . The support of his Islamist movement for the JEM is said to constitute a particular threat potential for the Sudanese government. After the general secretary of the force split off with his own faction, the strength of the JEM was estimated at 2000 to 4000 fighters at the beginning of 2008. It is the only group in whose self-image Islam plays a central role. The commitment to strict Islam dominates, at least in theory, over loyalty to one's own clan. After the death of Khalil Ibrahim in an air raid on December 24, 2011, his older brother Jibril Ibrahim was elected as his successor in January 2012. The JEM has been considered weakened since then.

- Various splinter groups from the JEM and the SLA have come together to form the United Resistance Front (URF). They have retreat bases in Chad and receive support and instructions from the government there. The relationship with the SLA Unity is considered good.

- A smaller group that operates on behalf of the Chadian government in the border area and had around 200 fighters in 2007 is called the National Movement for Reform and Development (NMRD). It was part of the JEM until 2004.

- The leader of the SLA Free Will (SLA-FW) was Abdel Rahman Musa until the end of 2006. At the beginning of 2007 he was appointed Minister of State in Khartoum. In September 2006, Commander Ahmed Saleh, who had jumped from the SLA / M, was added as a new or additional leader. The group consists largely of black African Birgit, but fights with the methods of the Arab cavalry militias on the side of the Sudanese government. Your area of operation is a district east of Nyala. The main opponents, alongside the civilian population, are SLA / M and JEM.

Smaller rebel groups, which no longer existed in 2009, and coalitions between the groups were not listed.

Course of the conflict

2003

The attack by the SLA on Gulu in the Marra region west of El Fasher, which began on February 25 and ended with the occupation of the town, is considered to be the beginning of the civil war. In the days that followed, Tiné, a Zaghawa center on the Chad border, was captured. There had been attacks on army posts and police stations a year earlier. This was followed by further attacks by SLA and JEM in the region, especially on El Fasher and Mellit (north, in Berti area), carried out with Kalashnikovs and bazookas and coordinated via satellite telephones.

The first major victory was the capture of the garrison town of El-Fasher in June with hundreds of rebels and dozens of vehicles, in which, according to the Sudanese government, 75 soldiers were killed, weapons stolen and four military helicopters and two Antonov planes destroyed. Some of the rebels were better armed than the Sudanese army. The Janjawid cavalry militias were therefore armed and were supposed to relieve the forces bound in South Sudan in a proxy war. The civilian population got more and more between the fronts. From this time on, the cavalry militias in particular were held responsible for attacks on villages, looting and the organized use of sexual violence.

2004

On April 8, 2004, the rebels and the Sudanese government signed a ceasefire agreement in N'Djamena , the capital of Chad, through the intermediary of the Chadian President and the African Union .

Of human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch , Amnesty International and the Society for Threatened Peoples of the Sudanese government were systematic massacres against civilians accused, mainly because of the support of the Janjaweed. Comparisons were made with the 1994 Rwandan genocide and Human Rights Watch deemed the systematic extermination to be proven. Thousands of Sudanese had already died in "ethnic cleansing" operations, and hundreds of thousands were forced to flee. The country was threatened with famine.

On July 30, 2004, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1556, which authorized the deployment of African Union military observers as part of the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS). The German federal government supported the AMIS with the first use of air transport forces of the Luftwaffe to move 196 Gambian soldiers and about twelve tons of cargo. The German participation began on December 16, 2004 and ended as planned on December 23, 2004.

2005

International aid was inadequate until 2005 and the international community was divided. While a number of states, including Great Britain, the USA and Germany, criticized the government in Khartoum, in some cases harshly, countries like Russia and the People's Republic of China prevented more decisive action. Economic interests, especially oil concessions, play a role in both. AMIS troops could do little to counter human rights violations in Darfur. Their mandate was limited to protecting observers. They were dependent on the goodwill of the Sudanese government in terms of supplies and their mobility was limited by insufficient equipment. In 2005, the AMIS had only eight civil helicopters without night vision systems.

Due to the ongoing dramatic situation in Sudan, on April 22, 2005 the German Bundestag approved the deployment of military observers in the south and east of the country as part of the UN mission UNMIS . The contingent consists of 75 unarmed military observers and staff. The deployment costs for the mission, which is initially planned for six months, amount to 1.3 million euros. The aim was to monitor the implementation of the peace agreement.

For the first time in the history of Africa, NATO intervened at the end of May 2005 after the African Union asked for logistical support for the peacekeeping force in the Sudanese crisis region of Darfur. NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer made it clear that the Alliance will not send any troops into the area. Rather, it is currently about planning capacities and logistics.

On December 13, 2005 , after receiving a report on the situation from Luis Moreno Ocampo , chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague , UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called for those responsible to be charged. In April, Moreno Ocampo Kofi Annan had given a list of the names of 51 suspects.

From December 17th to 18th, rebels took the border town of Adré in eastern Chad. According to the Foreign Minister of Chad, Chadian soldiers launched a counterattack on December 18, during which the attackers were repulsed and pursued as far as Sudan. The attackers' bases in the Sudan were also destroyed. 300 people are said to have been killed on the part of the rebels. The rebels are Chadian soldiers who deserted in September 2005 and, according to Chadian reports , are being supported by the government in Khartoum in order to take action against the SLA. This was denied by Sudan. The rebels, however, spoke of only 9 dead on their side.

On December 23, Chad stated that the country was at war with Sudan. This assessment would be based on the repeated raids on the border area supported by Sudan. However, this statement is not a declaration of war on Sudan. To this end, the Ambassador of Sudan had been appointed to the Chadian Foreign Ministry in N'Djamena , where he was given a list of the “aggressions by Sudan against Chad”.

2006

January February

At the beginning of the year, the attacks spread to villages of black African ethnic groups in Chad. The situation for the people in the refugee camps along the border had worsened. Human Rights Watch indicated that more refugees would run out of food in the border area.

The Sudanese government denied allegations of supporting the militias on February 6, 2006. Sudan's Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Samani al-Wasiyla , pointed out that Chadian rebels would be disarmed if encountered and accused Human Rights Watch of relying only on third and fourth hand statements.

April May June

According to Human Rights Watch, Sudan began a new military offensive in South Darfur on April 24, 2006. According to sources not mentioned in the Sudanese government, Sudan had informed the AU peacekeeping forces that they wanted to clear the road from Nyala to Buram .

As a result, the veto powers Russia and China stayed away from a vote in the UN Security Council on April 25, 2006, in which a resolution was passed imposing sanctions on four people involved in the Darfur conflict. These were two rebel leaders, a Janjawid leader and a former Air Force officer. The sanctions also include a travel ban and the freezing of all personal accounts abroad.

On May 5, 2006, the Sudanese government and the Minni Arcua Minnawi SLA / M signed a peace agreement in Abuja . All other rebel groups rejected the agreement because they did not see their main demand for the immediate creation of a Darfur region instead of the three states and the establishment of a second vice-president for Darfur met.

The agreement includes the following points:

- Armistice between the parties involved

- Disarming the Janjawid militias before disarming the other rebel groups (SLA and JEM)

- Incorporation of 4,000 rebels into the Sudanese armed forces

- Incorporation of 1000 rebels into the local police units

- Training / advanced training of 3000 rebels

- Seventy percent of the seats in the Darfur state legislatures for the rebels

- Creation of the post of "Chief Advisor to the President" for Darfur (gets fourth rank within the government)

- Referendum in Darfur to create a Darfur region instead of the current three states

- Compensation payments, establishment of a reconstruction and development fund for Darfur

The agreement was reached after two years of negotiations by the African Union under chief negotiator Salim Ahmed Salim and the support since May 1st by the US Deputy Foreign Minister Robert Zoellick . On June 27, 2006, members of Minnawi's SLA / M announced that they would not comply with the agreement and distanced themselves from their leader. On June 30, 2006, as a result of the Abuja Agreement, various rebel groups temporarily established a loose alliance under the name of the National Redemption Front (NRF) on the initiative of the JEM . It was another loss of power for Minnawi. The SLA faction around Abdelwahid al-Nur did not join this alliance. The agreement was not implemented.

July August

After the AU conference in Banjul , Gambia , the President of Sudan, Umar al-Bashir , proposed on July 3, 2006 to finance the AU's AMIS peace mission in Darfur for the next six months. This is to prevent a deployment of UN soldiers in Darfur, which Sudan rejects. Bashir expressed fear that Western soldiers could provoke terrorist activities in Sudan.

Also on July 3, 2006, the NRF declared the ceasefire agreement concluded in 2004 to be terminated after JEM troops and splinter groups attacked the city of Hamrat al-Sheikh in northern Kurdufan on the same day . This city is around 200 km west of Khartoum on the way to al-Ubayyid and around 400 km from the Darfur region. As a reaction to the termination of the ceasefire agreement by the NRF, attacks on the NRF surrounding al-Fashir in northern Darfur by the Sudanese army and Janshavid militias broke out on July 28, 2006.

By decree of President al-Bashir, Minawi was appointed Chief Assistant to the President . Al-Bashir thus fulfilled the agreement of the Abuja peace accord. On August 7, 2006, Minawi was sworn in in his new office and is thus formally head of the as yet semi-autonomous government of the Darfur region.

The Sudanese military launched a new offensive on August 28, 2006 in the area around al-Fashir in northern Darfur against the rebels of the NRF.

On August 31, the UN Security Council passed resolution 1706 , in which it was decided to send UN troops to Darfur. It cites Sudan's consent as a prerequisite for the deployment of around 20,000 UN soldiers and police units to replace the AU troops in Darfur, since their mandate ends at the end of September 2006. The resolution was put to a vote at the instigation of the veto powers USA and Great Britain, whereby the states of China, Russia and Qatar did not take part in the vote. Sudan had already made it clear in the run-up to the vote that it would not consent to the dispatch of UN troops and repeated its rejection after the resolution was passed.

September

After the expansion of the offensive on August 28, 2006, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan stated on September 11, 2006 that the military actions and troop reinforcements were "illegal" as they violated the Abuja peace agreement between the government and the Minawi SLA called for an immediate end to these actions and the admission of UN troops. The UN envoy for Sudan, Yasir Abdelsalam, stated that the government was committed to the peace agreement and that an additional 6,000 troops should be transferred to Darfur by the end of September 2006 and another 10,000 by the end of 2006 in order to implement the peace agreement. He received support from the states of the Arab League and the Organization of the Islamic Conference , which are opposed to sending UN troops to Darfur.

On September 25, 2006, the African Union decided to extend the AMIS mission by three months to December 31, 2006 and to increase the troops by 4,000 men to 11,000. The additional troops are to come mainly from Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Senegal, which currently already provide a large part of the AU troops. The day before, the President of Sudan announced again that the Sudanese government would deploy troops, regular soldiers and police officers, to work with the AU troops to protect civilians and refugees.

With a decree of the Sudanese President on September 27, 2006, the introduction of a transitional government for the Darfur region was decided. Minni Minawi should be in charge. The interim government should be appointed by Minawi and continue to include the governors of the three states of the Darfur region. Further decrees of the Sudanese president order the establishment of committees to compensate war refugees, to clarify the demarcation of the border in the north of Darfur and to rehabilitation and resettlement in Darfur. These measures are in line with the May 2006 peace treaty.

The UN representative in Sudan, Jan Pronk , said on September 28, 2006 that an imminent UN mission in Darfur would not take place and called for support - especially in financial terms - and for an unreserved extension of the AU mission. On September 29, 2006, the EU provided 30 million euros and the USA 20 million dollars for the AU mission.

2007

On January 10, 2007, the Sudanese government and rebel groups in Darfur agreed on a 60-day ceasefire and participation in a peace conference to be held before March 15, 2007, organized by the African Union and the United Nations. The beginning of the ceasefire was not officially agreed and should be determined by the African Union and the United Nations. On January 12, 2007, the JEM rejected reports of an agreement with the government on a ceasefire as untrue.

On February 4, 2007, President al-Bashir installed leaders and members of the SLA / M in posts that were granted to the rebels after the peace agreement. Abdelrahman Musa Abakar was appointed Minister of State in the Ministry of the Council of Ministers and Ibrahim Musa Madibo was appointed Chairman of the Darfur Rehabilitation and Relocation Commission . In addition, 12 people from the SLA / M were appointed as members of the National Assembly. The appointment came after Chinese President Hu Jintao made it clear during a state visit to Sudan that the Darfur issue must be resolved by Sudan itself.

In June, after months of resistance, the government of Sudan agreed to a mixed peacekeeping force from the African Union (AU) and the United Nations for Darfur. On July 31, 2007, the UN Security Council voted unanimously in favor of this peacekeeping force with Resolution 1769 . As part of the Hybrid Deployment Mission of the African Union and the United Nations in Darfur (UNAMID) - the world's largest peacekeeping mission - the first 9,000 military personnel were stationed in Darfur from October and the approximately 7,000 peacekeeping soldiers of the African Union Mission in Sudan were reinforced. On December 31, 2007, operational management was transferred from AMIS to UNAMID. The UNAMID plans to station a total of 20,000 military personnel and 6,000 police officers.

At the beginning of August, eight Mayur rebel groups in Arusha agreed on a common position for planned peace negotiations with the Sudanese government. However, some groups, including a faction of the SLA, stayed away. On September 30, 10 AU soldiers were killed in the heaviest attack to date on an AMIS base in Haskanita . Rebel factions were suspected as attackers.

2008

Despite the deployment of UNAMID peacekeepers, the fighting in Darfur continued. The UN spoke of an “open war with offensives and counter-offensives by the civil warring parties”. The situation was exacerbated by the outbreak of new fighting in Chad , which is increasingly suffering from refugee flows from Sudan .

On July 8, 2008, seven UNAMID blue helmets died and 22 others were injured, some seriously, when a joint patrol of 17 armed UN soldiers and unarmed observers between Gusa Jamat and Wadah in North Darfur of around 200 attackers on horses and in vehicles who were armed with heavy machine guns, was shot at and forced into a two-hour gun battle. The attack claimed the worst victims among UNAMID forces since the mission began. Given the situation in Darfur, China is coming under increasing pressure to act as a mediator. Peace activists and politicians called on the country to stop supporting the Sudanese government. At the same time, UN Secretary General Ban urgently called for additional troops to strengthen the UNAMID mission.

2009

In February 2009 less than half of the planned 26,000 UNAMID peacekeepers were on site. On March 4, the International Criminal Court in The Hague issued an arrest warrant for President al-Bashir in connection with the Darfur crisis . The arrest warrant was almost unanimously rejected by the African Union (AU). Since then, Bashir has traveled several times to African countries to show that he should not expect arrest. Only Chad and Botswana declared at the beginning of July 2009 that they would not adhere to the AU resolution and would arrest Bashir on their territory.

Since May, Khartoum has again accused the government of Chad of having repeatedly attacked targets on Sudanese territory with its air force and also of supporting the Darfur rebels with ground troops. The government of Chad stated that the attacks were directed against rebel positions in their own country. Planned peace negotiations fail not only because of the renewed attacks, but also because the rebels are still split into more than 20 groups.

At the end of July, the UN Security Council decided to extend the mandate for the UNAMID peacekeeping force by one year.

The 15-member body of the UN Security Council passed a resolution at the beginning of October according to which the monitoring of the arms embargo in Darfur, which has been in force since 2005, will be extended by one year. UNAMID had 19,000 soldiers and police forces in the area in October. At the same time, a report stated that the arms embargo was being undermined on both sides. Chinese arms sales to the Sudanese government were forwarded to Darfur, on the other hand, the Darfur rebels from the Government of Chad from Arab countries were coming Technicals .

2010

On February 23, after negotiations between representatives of the Sudanese government and a JEM delegation, a twelve-point framework agreement was signed in Doha , including a ceasefire and future participation of the JEM in the government in Darfur. A final peace agreement between the two parties is still pending. The SLA leader Abdelwahid al-Nur declared his rejection in Paris and named the prior disarmament of the government militias as a condition for negotiations. Abdelwahid al-Nur also rejected the Abuja Agreement in 2006, at that time together with the JEM. The other smaller rebel organizations were not involved in the talks this time either.

2011

The independence referendum held in mid-January in South Sudan , in which the large majority of South Sudanese voters voted for independence, and the formal independence of the South declared on July 9, have so far not had a calming effect on the fighting in Darfur, which continues to be regular is reported. On February 1, the South Sudanese Vice President Riek Machar expressed fears that the ongoing Darfur conflict could spread to the south and strain negotiations with the al-Bashir government over the border in the Abyei oil region .

In November, renewed talks took place in Washington between the rebel organizations JEM and Minni Minnawis SLM and the Sudanese government with the declared intention of implementing the Doha Agreement of 2006. The US government has expressed its support for this.

On December 24th, Khalil Ibrahim , leader of the JEM, was killed in an air raid . Weapons support for the night raid came from Libya and Qatar .

2013

A splinter group that split off from the JEM in September 2012 held direct peace talks with the Sudanese government in Doha in January 2013 , which were originally scheduled for December 2012. Regardless of this, some insurgent groups want to form an organizational platform to overthrow the government together.

In the first half of the year there were several disputes over the Jebel Amer gold mines in North Darfur, where a third of Sudan's gold is mined. Arab Abbala tribesmen, supported by the Sudanese government, tried to remove control of the area from the Beni Hussein tribe resident there. According to UN figures from May, 150,000 residents of the area had to flee from the Abbala attackers. According to this, the Abbala militias act as auxiliaries for the state.

In August, a prolonged dispute over pastureland for cattle between the two Arab tribes Rizeigat and Maalia near the town of ad-Du'ain in East Darfur escalated. Around 100 people died in the fighting.

2016

According to Amnesty International, government forces began a large-scale military offensive in the Jebel Marra region in January 2016, consisting of coordinated air and ground strikes. The government troops were also accused of serious human rights violations. There are also specific indications that the government used chemical weapons against the civilian population. According to this, between 200 and 250 people are said to have died as a result of contact with chemical weapons.

With the Chadian President Idriss Déby as mediator, indirect negotiations between the Sudanese government and two rebel groups from Darfur took place in Ndjamena at the beginning of June 2016 with the aim of reaching a peace treaty in accordance with the Doha Agreement concluded in 2010. But even the renewed attempt to bring about a peaceful solution to the civil war has so far failed.

2017

In October the Sudanese government announced that from October 15, 2017, a mandatory arms levy would be set up in Darfur to collect and destroy weapons from rival tribes. However, since some of them had already declared their opposition, further fighting in Darfur was feared. Nevertheless, the action in November brought some improvement to the security situation. At the end of December, the Sudanese government forces were about to collect weapons in the controlled area of the SLA of Abdelwahid Mohamed al-Nur (SLM-AW / SLA-AW) in Jebel Marra .

2018

The gradual withdrawal of UNAMID , which has been stationed in Darfur since 2007 and which was accompanied by the closure and return of eleven of its camps to the Sudanese government in 2017, continued in 2018 and, according to a statement by the State Secretary in the Sudanese Foreign Ministry, Abdel-Ghani al-Na ' in September 2018 to be completed within two years.

In December, representatives of the Sudanese government and two rebel groups - the JEM and the SLM-MM - signed an agreement in Berlin that should pave the way for peace negotiations planned in Qatar in 2019 .

2019

According to a report from March 2019, UNAMID will have completely withdrawn from East Darfur, West Darfur and South Darfur by June.

In February 2019, President al-Bashir promised to end the armed conflict in Darfur by the end of the year. On April 11, there was a military coup in Sudan , in which al-Bashir was overthrown.

Humanitarian aid

The European Union financed most of the costs of the AMIS observer mission from 2004 to 2006 with US $ 200 million . For AMIS, 32 warehouses were built by December 2005 to accommodate a total of 9,300 employees. However, it could not have any significant influence on the fighting. The decision-making monopoly for the mission lay with the African Union , which refrained from criticizing the Sudanese government, on which the mission was dependent for its practical implementation. As part of the AMIS, aid began to be supplied, which Khartoum left entirely to foreign NGOs . This division of labor was already an advantage for the government in the South Sudanese civil war, where the Sudanese government had benefited from Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS), which had been carried out to combat famine since 1989 . In the spirit of the peace talks between North and South Sudan in 2003, the European Union made 400 million euros available for reconstruction in the south and the same amount for the north.

The same aid organizations that were active in South Sudan have relocated or expanded their operational area to Darfur. In April 2004 there was still little foreign aid in Darfur, there were only 222 NGO employees on site, some of whom were involved in development aid and not in disaster relief . By July 2004, the EU had spent 88 million euros on refugee aid in Darfur. During the worst fighting and the widespread destruction of villages in November 2004, Commissioner Poul Nielson lamented that food transport was not safe. In December the British organization Save the Children , which had worked in Darfur for 20 years , withdrew after the death of four of its employees. In October 2005 there were almost 14,000 humanitarian workers from the UN and 82 NGOs.

According to its own statement, the largest donor is the United States, which made available US $ 681 million for humanitarian aid from October 2003 to September 2006 through the United Nations World Food Program (WFP) and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement . Of the money, which mostly flowed into refugee camps, around two thirds were earmarked for food deliveries, the rest was used, among other things, to build accommodation and to supply drinking water. The approximately $ 23 million portion of this amount for the Red Cross was intended for people who had stayed in their homeland. Due to acts of war, kidnappings by bandits or government travel restrictions, access to those in need was often not possible or only to a limited extent. In January 2006, the UN aid personnel had to be withdrawn from West Darfur for two months, and in July 2006 460,000 people in North Darfur were cut off from aid deliveries. Checkpoints often obstruct access to areas controlled by rebels.

In April 2006, WFP officials said they had received only a third of the $ 746 million pledged. The food rations had to be reduced from 8800 kJ per person per day to 4400 kJ due to late and insufficient funding . UNICEF complained about an increasing malnutrition rate among the population.

At the end of 2007, the green helmets of the AMIS were replaced by the blue helmets of the 9,000 UNAMID soldiers. However, attacks on aid convoys increased; In March 2008, the WFP went missing 37 trucks, as a result of which aid supplies for the estimated 2 million needy were reduced by 50 percent. In September 2008, access to 250,000 people in need was inaccessible, according to Human Rights Watch. The Sudanese government continued to be accused of using bureaucratic measures to impede aid. In the first nine months of 2008, 170 humanitarian workers were abducted and 11 killed. By October 225 vehicles had been stolen by aid organizations, in 2007 there were 137. In August 2008, 415,000 people were temporarily without support when two larger NGOs had to stop their work due to repeated attacks. The agreements made regarding humanitarian aid are not being respected by either the government or the rebels. The attack by a heavily armed militia on a UNAMID patrol on July 8, 2008, in which seven peacekeepers were killed, was only the largest single incident. In 2008, at least 34 UN employees were killed.

Another low blow for the affected population is the expulsion of 13 aid organizations from Sudan on March 4, 2009. They had cared for the majority of the 2 million people who were dependent on food. It was President al-Bashir's response to the International Criminal Court's indictments against him. JEM leader Khalil Ibrahim used this measure as an opportunity to demand that the UN Security Council set up an "oil-for-food program" with which the Sudanese government's oil revenues should be forcibly diverted into food aid. Since then, the aid to the affected population has decreased significantly because the Sudanese government is not ready or able to take on the emergency aid. It is partly continued by the remaining local employees of the organizations concerned. The computers and vehicles of the expelled NGOs were confiscated and their leaders detained in Khartoum for the financial settlement of their deportation. They had allegedly violated Sudan's right to dismiss by their “self-inflicted” eviction and were therefore obliged to pay each of their Sudanese employees six months' salary. The corresponding law for these severance payments was specially created. Western foreigners still working in a region that no longer has clear front lines are increasingly exposed to the risk of kidnappings with ransom demands.

Legal responsibility

The international discussion on Darfur was dominated by two main themes: In July 2004 the United States Congress passed a resolution according to which the crimes of the Sudanese government and the Janjawid in Darfur were to be described as genocide ( genocide ). The American Save Darfur Campaign and other organizations had previously called for the use of this term with reference to the genocide in Rwanda . According to the UN resolution of 1948 , a situation declared as genocide would force the signatory countries to intervene, whereby, based on the legal definition, the intent and responsibility of the Sudanese government for the murders directed against an entire people must be demonstrable. Because of this difficulty in establishing evidence, the term is not used by the United Nations, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch . The latter resort instead to the terms “ethnic cleansing”, “ crimes against humanity ” and “ war crimes ”.

From the discussion about the term genocide, the question of the criminal consequences arose. With UN Security Council Resolution 1593 , the International Criminal Court (ICC) was authorized to investigate the situation in Darfur. As a result of these investigations, the ICC issued arrest warrants in 2007 against the Sudanese Minister of State for Humanitarian Affairs Ahmad Harun and the Janjawid leader Ali Kushaib . These two people are believed to be responsible for crimes committed by the Janjawid. Sudan does not recognize the jurisdiction of the ICC and refuses to extradite those wanted.

On July 14, 2008, the chief prosecutor of the ICC announced that he would apply for an arrest warrant for genocide against Sudanese President al-Bashir . UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon , the African Union , the Arab League and the government of Sudan itself expressed concerns. Nevertheless, in early March 2009 the International Criminal Court issued the requested arrest warrant. This was issued - contrary to the motion of the chief prosecutor - solely for crimes against humanity and war crimes, but not for genocide. A new arrest warrant against al-Bashir, which the ICC issued on July 12, 2010, also includes charges of genocide.

No conclusion

In July 2008, around 4.5 million people were affected by the conflict. Of these, 2.5 million were displaced within the region and another 2 million people were dependent on aid supplies, according to UN estimates. In 2007, 230,000 people fled Darfur to Chad, 110,000 had been made homeless in Chad and 150,000 within the Central African Republic. The negotiations in Abuja in 2006 failed and the peace agreement was not implemented. On the contrary, after the signing there were further splits within the rebel movement, resulting in increasing violence. Since that time, small rebel groups have increasingly slipped into the area of ordinary crime, often only gaining possession of vehicles through theft. Between April and June 2008 alone, 70 vehicles were stolen by aid organizations. On-site aid is hampered by the poor security situation and government travel restrictions, but 17,000 helpers (mid-2008) are on duty. Air strikes by the Sudanese government and fighting between rebel factions were reported in all three regions of Darfur in 2008.

The Fur Sultanate, which existed from the 17th century to 1916, was ruled by the Keira dynasty, a social elite whose members included Fur and Zaghawa and whose historical myth, similar to that of Arab sultanates, went back to the Prophet. There was an identity that was oriented more geographically than ethnically to this once economically strong and politically influential border region. Festive events at the court were open to all ethnic groups. Ethnic constructions were called into question by frequent mixed marriages. In the 1970s, all lands (Dar) were more or less ethnically mixed, with the smaller groups or new settlers being forced to obey the customary law of the larger group. A look back at the “ideal world” stands in the way of the fact that new political identities were formed through civil war and displacement and the availability of weapons has changed the previous distribution of power. The increasing fragmentation of the individual warring parties towards the formation of gangs is the result of traditional power structures that have been lost. On the other hand, there are new social classifications: Sheikhs , who previously had only a small community around them, can increase their following in refugee camps, people can gain self-confidence in social aid projects and that - on a small scale - from the FAO in particular Dairy goats or donkeys given out to women who are household heads are a contribution so that they can participate in the economic bartering of their community.

See also

- Civil War in South Sudan

- Conflict in East Sudan

- Darfur Now (documentary)

- The Death Riders of Darfur (Documentary)

- Darfur (feature film)

- Tomo Križnar , Slovenian peace activist, film and photographic documentation on Darfur and the Nuba Mountains produced

- 17 Musicians in Search of a Sound: Darfur (Jazz album)

literature

- Atta El-Battahani: Ideological, Expansionist Movements and Historical Indigenous Rights in the Darfur Region, Sudan. From mass murder to genocide . In: Zeitschrift für Genozidforschung No. 5/2 2004, pp. 8–51.

- Kurt Beck: The massacres in Darfur . In: Zeitschrift für Genozidforschung No. 5/2 2004, pp. 52–80.

- Martin W. Daly: Darfur's Sorrow: A History of Destruction and Genocide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007 ISBN 0-521-69962-2

- Hatem Elliesie: The Darfur Crisis in Sudan and International Law: A Challenge for the United Nations (UN) and the International Criminal Court (ICC). In: Constitution and Law in Übersee, Volume 40, 2007, pp. 199–229, ISSN 0506-7286

- Hatem Elliesie, together with Urs Behrendt and Niway Zergie Aynalem: Different Approaches to Genocide Trials under National Jurisdiction on the African Continent: The Rwandan, Ethiopian and Sudanese Cases . In: Recht in Afrika, 12/1, Cologne 2009, pp. 21–67. ISBN 978-3-89645-804-9

- Hatem Elliesie: Sudan under the Constraints of (International) Human Rights Law and Humanitarian Law: The Case of Darfur . In: Hatem Elliesie (Ed.): Contributions to Islamic Law VII: Islam und Menschenrechte / Islam and Human Rights / al-islam wa-huquq al-insan. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2010, pp. 193–217. ISBN 978-3-631-57848-3

- Robert Frau: The relationship between the permanent International Criminal Court and the Security Council of the United Nations - Art. 13 lit. b) ICC statute and the Darfur conflict before the court . Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, Schriften zum Völkerrecht Volume 192, 2010, pp. 300–363; ISBN 978-3-428-13225-6 .

- Julie Flint: Rhetoric and Reality: The Failure to Resolve the Darfur Conflict. Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2010

- Amanda F. Grzyb (Ed.): The world and Darfur: international response to crimes against humanity in Western Sudan. McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 2009, ISBN 978-0-7735-3535-0

- Khalid Y. Khalafalla: The conflict in Darfur . In: From Politics and Contemporary History 4/2005, pp. 40–46

- Gérard Prunier : Darfur. The “ambiguous” genocide , Hamburger Edition, 2007, ISBN 978-3-936096-66-8 Review by K. Platt

- Thilo Thielke: War in the land of the Mahdi. Darfur and the disintegration of Sudan. Magnus Verlag, Essen 2006, ISBN 3-88400-505-7

- Samuel Totten, Eric Markusen (Ed.): Genocide in Darfur: Investigating the Atrocities in the Sudan. New York 2006, ISBN 978-0-415-95328-3 .

- Alex de Waal and Julie Flint: Darfur: A Short History of a Long War. Zed Books, London 2006, ISBN 1-84277-697-5 .

Web links

- Birgit Strube-Edelmann: The Darfur Conflict - Genesis and Course. Scientific Services of the German Bundestag 2006 (PDF file; 771 kB)

- Victor Tanner: Rule of Lawlessness: Roots and Repercussions of the Darfur Crisis. Sudan Advocacy Coalition, January 2005. Sudan Open Archive, Rift Valley Institute

- Hassan Tai Ejibunu: Sudan Darfur Region's Crisis: Formula for Ultimate Solution. ( Memento from September 19, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) European University Center for Peace Studies. Research Papers 09/08, Stadtschlaining 2008 (PDF file; 509 kB)

- Peter Mühlbauer: Darfur - Ethnography and History of a Conflict . telepolis, June 2007:

- Marc Lacey: A Tree That Supported Sudan Becomes a War's Latest Victim:, New York Times, May 15, 2004

- "Eyes on Darfur" Amnesty International shows the destruction using satellite images

Individual evidence

- ^ Time for Justice in Darfur. Amnesty International, July 17, 2007

- ↑ Darfur dead 'could number 300,000. Guardian, April 23, 2008

- ↑ Eric Reeves: Reckoning the Costs: How many have died during Khartoum's genocidal counter-insurgency in Darfur? What has been left in the wake of this campaign? sudanreeves.org, November 12, 2017

- ↑ Humanitarian Bulletin Sudan, No. 11/7, OCHA, March 13, 2016

- ↑ Alex de Waal: Who are the Darfurians? Arab and African Identities, Violence and External Engagement. Social Science Research Council, December 10, 2004 ( Memento of July 28, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Younes Abouyoub: Climate: The Forgotten Culprit. The Ecological Dimension of the Darfur Conflict. In: Race, Gender & Class , Vol. 19, No. 1/2, 2012, pp. 150–176, here p. 154

- ↑ Abduljabbar Abdalla Fadul: Natural Resources Management for Sustainable Peace in Darfur. In: University for Peace (Ed.): Environmental Degradation as a Cause of Conflict in Darfur. Khartoum, December 2004, p. 35 ( Memento from June 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.3 MB)

- ↑ Rex Sean O'Fahey: Conflict in Darfur. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. In: University for Peace (Ed.): Environmental Degradation as a Cause of Conflict in Darfur. Khartoum, December 2004, pp. 23–32 ( Memento from June 19, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.3 MB)

- ↑ Rainer Tetzlaff: Ethnic conflicts in Sudan. In: Sigrid Faayth, Hanspeter Mattes: Wuquf 7–8. Contributions to the development of the state and society in North Africa. Hamburg 1993, pp. 156-158

- ↑ Ban Ki Moon sees climate change as a warmonger in Darfur. Spiegel Online, June 18, 2007

- ↑ Eric Reeves: On Ban Ki-moon, Darfur, and Global Warming. The Guardian, June 20, 2007

- ^ Mohamed Suliman: Warfare in Darfur. The Desert versus the Oasis Syndrome. In: G. Bachler, K. Spillmann (Eds.): Environmental Degradation as a Cause War. Ruegger, Zurich 1996

- ^ Mohamed Suliman: Civil War in Sudan: The Impact of Ecological Degradation. In: Contributions in Black Studies, Volume 15, Article 7, 2007, pp. 99–121, here pp. 118f

- ↑ Michael Kevane, Leslie Gray: Darfur: rainfall and conflict. In: Environmental Research Letters 3 (2008), doi : 10.1088 / 1748-9326 / 3/3/034006 .

- ^ Mohamed Suliman: Warfare in Darfur. The Desert versus the Oasis Syndrome. In: G. Bachler, K. Spillmann (Eds.): Environmental Degradation as a Cause War. Ruegger, Zurich 1996, Table 6: List of “tribal” conflicts in Darfur. (Table shows previous conflicts and their triggers)

- ^ Gérard Prunier: Standoff in Chad. The epicenter of the Central African crisis is in Khartoum. Le Monde diplomatique, March 14, 2008

- ↑ Julie Flint, Alex de Waal: Ideology in Arms: The Emergence of Darfur's Janjaweed. ( Memento of January 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Sudan Tribune, August 30, 2005

- ↑ Fabricie Weissmann: Humanitarian dilemmas in Darfur. ( Memento of April 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 307 kB) Médecins sans Frontières, July 2008, p. 2

- ↑ René Lemarchand: Unsimplifying Darfur. In: Genocide Studies and Prevention, 1, 1, University of Toronto Press, July 2006, pp. 1–12 (PDF; 88 kB)

- ^ The War in Darfur: A Reference of the Most Important Players. ( Memento of February 1, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) POOT Resources, August 2008 (PDF; 93 kB) List of political and military leaders in Darfur

- ↑ "Men with no Mercy." Rapid Support Forces Attacks Against Civilians in Darfur, Sudan. Human Rights Watch, September 2015

- ↑ Letter dated April 19, 2006 from the Chairman of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1591 (2005) concerning the Sudan addressed to the President of the Security Council. United Nations Security Council, pp. 31-33

- ^ Report of the Secretary General on the Deployment of the African Union - United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur. United Nations Security Council, July 7, 2008, p. 4 (PDF; 65 kB)

- ↑ Khalid Abdelaziz, Alexander Dziadosz: Darfur's strongest rebel group elects new chief. Reuters, January 26, 2012

- ↑ Darfur Humanitarian Profile No 32. ( Memento of April 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Office of UN Deputy Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Sudan. UN Resident and Humanitarian Co-ordinator, July 1, 2008, p. 13 (PDF; 692 kB)

- ^ Jérôme Tubiana: The Tchad-Sudan Proxy War and the "Darfurization" of Tchad: Myths and Reality. The Small Arms Survey. Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva, April 2008 (PDF; 617 kB)

- ^ Victor Tanner, Jérôme Tubiana: Divided they fall. The Fragmentation of Darfur's Rebel Groups. Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva 2007

- ↑ In Sudan, Death and Denial. The Washington Post, June 27, 2006

- ↑ Sudan: Darfur: Rape as a weapon of war: sexual violence and its consequences. Amnesty International, July 19, 2004

- ^ April 2004 Humanitarian Ceasefire Agreement on the Conflict in Darfur. Text of the Armistice Agreement of April 8, 2004

- ↑ UNO - Press Release SC / 8160: Resolution 1556: Security Council Demands Sudan Disarm Militias in Darfur.

- ↑ Chad and Sudan before a war. www.news.ch, December 23, 2005

- ^ New attacks on villages in Chad. ( Memento of July 24, 2008 on the Internet Archive ) Human Rights Watch, February 5, 2006

- ↑ Sudan denies backing Chad raids. BBC News, February 6, 2006

- ↑ Sudan renews military attacks in South Darfur - HRW. ( Memento of May 4, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Sudan Tribune, April 26, 2006

- ↑ UN votes sanctions against four Sudanese over Darfur. ( Memento of May 19, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Sudan Tribune, April 26, 2006

- ^ Darfur rebel SLA-Minawi, Sudan govt agree peace deal. ( Memento of July 21, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Sudan Tribune, May 5, 2006

- ^ Darfur peace plan in Jeopardy. ( Memento of July 21, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Sudan Tribune, May 5, 2006

- ^ Two of three rebel groups refuse Darfur peace deal. ( Memento of July 26, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Sudan Tribune, May 5, 2006

- ↑ June 27, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Rebel SLM suspends Darfur Peace Agreement implementation" ( Memento of July 19, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ June 30, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Founding Declaration of Darfur's National Redemption Front" ( Memento of July 17, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ July 3, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan ready to fund AU peacekeepers in Darfur for 6 months" ( Memento from July 19, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ July 3, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Darfur rebel alliance attack town, declare truce over" ( Memento of July 19, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ July 30, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Darfur clashes undermine fragile peace deal" ( Memento of July 31, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ August 5, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan appoints former rebel leader as President's Senior Assistant"

- ↑ September 1, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan launches major offensive against Darfur rebels"

- ↑ September 1, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan rejects UN resolution on Darfur peacekeepers"

- ↑ September 12, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan's Darfur military action illegal - Annan"

- ↑ September 26, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "AU to increase Darfur troop strength to 11,000"

- ↑ September 28, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan sets up interim authority in Darfur"

- ↑ September 29, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "Pronk says UN forces in Darfur unlikely, calls for strategy change"

- ↑ September 30, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "EU loan saved Darfur peacekeeping mission - AU"

- ↑ September 30, 2006 - Sudan Tribune: "US provides $ 20 mln to African peacekeepers in Darfur"

- ↑ January 11, 2007 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan, Darfur rebels agree 60-day ceasefire"

- ↑ January 13, 2007 - Sudan Tribune: "Darfur rebel JEM denies 60-day truce with Sudanese government"

- ^ February 5, 2007 - Sudan Tribune: "Sudan names ex Darfur rebels in executive posts and parliament"

- ↑ February 5, 2007 - Sudan Tribune: "China's Hu tells Sudan it must solve Darfur issue"

- ↑ Sudan accepts AU-UN force in Darfur. Sudan Tribune, June 12, 2007

- ↑ United Nations : Security Council authorizes hybrid UN-African Union operation in Darfur. July 31, 2007

- ^ UNAMID takes over peacekeeping in Darfur. Unamid, December 31, 2007 ( Memento from August 28, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ BBC News: Darfur's rebel groups reach deal

- ↑ BBC News: Darfur attack kills peacekeepers.

- ^ Attacks against United Nations personnel continued unabated in 2008, United Nations Staff Union reports. Relief Web, January 12, 2009

- ^ Netzeitung : Nobel Peace Prize winners appeal to China. February 14, 2008 ( Memento from March 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ African Union dismisses criticisms on ICC resolution. Sudan Tribune, July 20, 2009

- ↑ Sudan accuses Chad of sending troops to aid rebels. Reuters, May 18, 2009

- ^ Sudan downplays prospects of normalizing ties with Chad. Sudan Tribune, August 6, 2009

- ^ 'Progress' at Darfur peace talks. BBC News, August 21, 2009

- ↑ https://www.un.org/press/en/2009/sc9765.doc.htm

- ^ Tide of munitions for Darfur war still flows despite embargo - UN report. Sudan Tribune, November 10, 2009

- ^ Sudan and JEM rebels agree to sign a final deal for peace in Darfur. Sudan Tribune, February 24, 2010

- ^ Machar Urges Resolution of Darfur Conflict, Vows to Settle Abyei Issue By March. Sudan Tribune, February 2, 2011

- ^ Washington pledges to support peace implementation in Darfur, Sissi. ( Memento of September 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Sudan Tribune, October 24, 2011

- ↑ Roman Deckert, Tobias Simon: New year, old conflicts. ( Memento of March 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Zenith online, January 17, 2012

- ^ Darfur peace talks between Sudan and rebel group kick off in Doha. Sudan Tribune, January 20, 2013

- ↑ Sudan says Darfur rebels willing to discuss peace, JEM denies. Sudan Tribune, January 24, 2012

- ↑ Khartoum behind fresh wave of violence over gold in Darfur: Report. Sudan Tribune, May 18, 2013

- ↑ More than 100 killed in tribal conflict in South Darfur. Sudan Tribune, August 11, 2013

- ↑ Jonathan Loeb: Did Sudan use chemical weapons in Darfur last year? Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 17, 2017

- ^ Sudan, two rebel factions discuss ways to hold peace talks on Darfur conflict. Sudan Tribune, June 4, 2016

- ↑ Darfur forcible weapons collection to start at mid-October. Sudan Tribune, October 3, 2017

- ↑ Weapons collection campaign increases risk of armed clashes in Darfur: Enough. Sudan Tribune, November 10, 2017

- ↑ Sudan says weapons collection operations will reach rebel areas in Darfur's Jebel Marra. Sudan Tribune, December 21, 2017

- ↑ UNAMID completes closure of 11 sites in Darfur . Sudan Tribune, October 23, 2017

- ↑ UNAMID full exit from Darfur to be completed within two years: FM. Sudan Tribune, September 24, 2018

- ^ Sudan, armed groups agree to resume talks for peace in Darfur. Sudan Tribune, December 7, 2018

- ^ UNAMID to fully exit three Darfur states by June. Sudan Tribune, March 30, 2019

- ↑ Sudan's Bashir pledges to end armed conflicts in 2019. Sudan Tribune, February 13, 2019

- ↑ FACTBOX NGOs respond to Sudan's Darfur crisis. AlertNet, October 8, 2004 List of aid organizations active in Darfur at the end of 2004

- ^ Jeppe Plenge Trautner: The Politics of Multinational Crisis Management: The European Union's Response to Darfur. ( Memento of February 1, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) SPIRIT, European Studies, Aalborg University, February 12, 2006, p. 19

- ↑ Darfur Crisis: Progress in Aid and Peace Monitoring Threatened by Ongoing Violence and Operational Challenges. United States Government Accountability Office, GAO, November 2006, pp. 25, 39 (PDF; 5.9 MB)

- ↑ Lydia Polgreen: UN cuts Darfur food aid as donations trickle away. International Herald Tribune, April 30, 2004

- ↑ Bandit raids cut Darfur food aid. BBC News, March 10, 2008

- ↑ Rhetoric vs. Reality. The situation in Darfur. ( Memento from February 23, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Save Darfur, December 2008 (PDF; 444 kB)

- ^ JEM leader calls for oil-for-food programs in Darfur. Sudan Tribune, March 7, 2009

- ↑ Andrea Böhm: Darfur - was there something? Time online, April 28, 2009

- ^ Andrew Heavens: Kidnappers demand ransom for Darfur aid staff. reuters.com, July 9, 2009

- ^ Colin L. Powell: The Crisis in Darfur. Written Remarks before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. ( Memento from January 20, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Washington DC, September 9, 2004 (speech by the then American Secretary of State)

- ↑ Harun's profile on TRIAL Watch ( Memento from May 23, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Profile of Kushayb on TRIAL Watch ( Memento from January 18, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Tribunal issues arrest warrant for Sudan's president. Spiegel Online, March 4, 2009

- ↑ New arrest warrant against Bashir for genocide. derStandard.at, July 12, 2010

- ↑ Eyes on Darfur / Amnesty International: Conflict analysis. ( Memento from November 26, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Darfur Humanitarian Profile No. 32. ( Memento of April 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 692 kB) Office of UN Special Deputy Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Sudan, July 1, 2008