Genocide in Rwanda

As Rwandan genocide extensive violence in are Rwanda referred, which began on 6 April 1994 and lasted until mid-July 1994th They killed around 800,000 to 1,000,000 people; the lowest estimates assume at least 500,000 deaths. In almost 100 days, members of the Hutu majority killed around 75 percent of the Tutsi minority living in Rwanda, as well as Hutu who did not participate in the genocide or who actively campaigned against it. The perpetrators came from the ranks of the Rwandan army, the presidential guard, the national police (gendarmerie) and the administration. The Impuzamugambi militias also playedand especially the Interahamwe played a particularly active role. Large sections of the Hutu civilian population also participated in the genocide. The genocide occurred in the context of a longstanding conflict between the then Rwandan government and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebel movement .

In the course of and after the events, the United Nations (UN) and states such as the USA , Great Britain and Belgium were criticized for their inaction. The focus was on the reasons why an early humanitarian intervention did not take place, or why the local peacekeeping forces of the United Nations , the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), were not strengthened but rather downsized when the violence broke out. In addition, France was charged with participating in the crimes.

The genocide in Rwanda also created significant regional problems. After the RPF drove out the Hutu rulers in order to end the genocide and form a new government, hundreds of thousands of Hutu fled to eastern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo ) in the summer of 1994 . Among the refugees were many perpetrators who then prepared for the reconquest of Rwanda. The Rwandan army used these activities as an opportunity to intervene in the neighboring country to the west.

prehistory

“Tutsi” and “Hutu” in pre-colonial and colonial times

The Rwandan state borders were already largely consolidated before the appearance of the European colonial powers . Under the reign of Kigeri Rwabugiri , who ruled Rwanda as king from 1853 to 1895, both limited regional expansion and state centralization tendencies began. Previously autonomous smaller regions in the west and north were incorporated into the rulership of Rwabugiris, and state power was centralized. In addition, a greater differentiation of the population groups began within the ruled area. The people who were mainly involved in cattle breeding, called "Tutsi", gained increasing power over arable farmers who were called "Hutu". The Twa , a third group who lived as hunters and gatherers, played no role in this change in the relations of domination. In the empire of Rwabugiri, the term “Tutsi” developed more and more into a synonym for members of the ruling class of an emerging central state, while the term “Hutu” became the name for the group of the ruled.

With the beginning of their colonial rule (1899-1919), the Germans interpreted the graduated social relations in Rwanda on the basis of the racist Hamite theory developed in Europe . They assumed that the Tutsi were Nilotes who immigrated to the area of the African Great Lakes centuries ago and were related to " Caucasian " and thus European peoples. This justifies their rule over the " Negro " ethnic groups of Central Africa , which are perceived as less high-ranking , to which the Hutu belonged in the eyes of the Germans. The colonial rulers incorporated the Tutsi as local power carriers into the system of their indirect rule .

In the course of World War I , after a series of limited skirmishes, the Belgians effectively took power in Rwanda before it was officially granted to them at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and Rwanda was declared a mandate of Belgium by the League of Nations in 1923 . The Belgians continued the indirect rule. They also considered the unequal distribution of power between Hutu and Tutsi to be the result of a racial superiority of the Tutsi.

The new colonial rulers introduced a system of forced labor with the help of which they wanted to develop the country economically. They also individualized the claims of their power against the individual by suppressing the influence of clans and lineages through administrative reforms. One of the most momentous administrative measures taken by the Belgians in 1933/34 was the issuance of identification documents in the wake of a census . These documents established the ethnicity of each individual, whether he was Twa, Hutu or Tutsi. From then on, the ethnic allocation of all Rwandans was recorded in administrative registers. The differentiation of people according to social status and economic activities was made biologized and thus to one according to races .

In the inter-war period , the Catholic Church promoted the Tutsi more strongly than the Hutu in its mission schools . This school education offered the Tutsi the prospect of entering the state administration, because lessons in French prepared them for it. After the end of the Second World War , the missionaries' self-image changed. They increasingly saw themselves as helpers and mouthpieces for the underprivileged Hutu, no longer as supporters of the Tutsi elite . Schools increasingly offered Hutu access to Western education. The emerging Hutu clergy belonged to the Hutu elite, which increasingly formed a counterweight to Tutsi rule and pushed for political participation and democratization of the country.

Hutu revolution and Hutu regime under Grégoire Kayibanda

In view of the foreseeable decolonization of Rwanda, the political debate became radicalized in the 1950s. Political parties formed along the “ethnic” borders. In their founding documents and programs, on the one hand, Tutsi parties demanded the continuation of the Tutsi monarchy , because this would correspond to the superiority of the Tutsi and the historical tradition of Rwanda. On the other hand, extremist Hutu politicians defamed the existing Tutsi hegemony as the rule of an alien race. Belgium began integrating Hutu into the administration of Rwanda in the 1950s. This aroused fears of the Tutsi of an imminent loss of power, without at the same time satisfying further claims of Hutu, who longed for sole power or at least for a decisive part of the exercise of power in Rwanda. A few months after the death of Mutara Rudahigwa ( Mutara III ), who had been appointed monarch in 1931, violence between Hutu and Tutsi escalated from November 1959. Several hundred people fell victim to the acts of violence before the Belgian administration could restore order.

After these events, the Belgians replaced half of all Tutsi in the administration with Hutu. The change was most evident at the mayor level. 210 of the total of 229 mayor posts were now occupied by Hutu. They replaced the former Tutsi mayors who were killed or fled in the course of the unrest. The traditional hierarchical orientation that previously ensured loyalty to the local Tutsi elite now helped the new local Hutu leaders, who in turn successfully appealed to the Hutu majority to belong together. These changes were the basis for the electoral victories of the Parmehutu (Parti du Mouvement et de l'Emancipation Bahutu) in 1960 and 1961, a Hutu movement that campaigned for the abolition of the monarchy, for the introduction of republican conditions, for the independence of Rwanda from Belgium and especially for the rapid end of Tutsi rule. This upheaval in political conditions went down in Rwanda's history as the Hutu Revolution .

Even before Rwanda's independence in July 1962, tens of thousands of Tutsi fled to Rwanda's neighboring countries. As leader of the Parmehutu, Grégoire Kayibanda consolidated the rule of the Hutu by taking over the presidency of the country and establishing a one-party state. Multiple guerrilla attacks by Tutsi refugees, some of which reached very far into the interior of Rwanda, were finally repulsed in 1967. At the same time, state violence in those years was repeatedly directed against the Tutsi who remained in Rwanda, who were said to have sympathy with the Tutsi guerrillas. It led to the expulsion of the Tutsi from certain parts of the country. It was often associated with attacks on the property, life and limb of the Tutsi. Around 20,000 Tutsis lost their lives as a result of these state-sponsored or tolerated attacks, and around 30,000 more fled abroad. All Tutsi politicians still living in the country were murdered. The Hutu regime has since blamed the threat posed by the Tutsi rebels for all of the country's major domestic political problems. At the same time, the Hutu constructed the myth, which was always reactivated in crisis situations, of a long, courageous and successful struggle against merciless oppressors.

Hutu and Tutsi until the late 1980s

In October 1972, another massive wave of violence was directed against the Rwandan Tutsi. President Kayibanda did not intervene so as not to jeopardize his power, which was being questioned by extremist Hutu - who called for retaliation against Tutsi in the face of the extensive massacre of Hutu in neighboring Burundi , in which around 100,000 to 150,000 Hutu were killed. It was not until February 1973 that the president stopped the acts of violence and thus attracted aggression from the extremist Hutu.

In the dispute between moderate and extremist Hutu groups, Defense Minister Juvénal Habyarimana took the initiative and took power in a coup on July 5, 1973 . Habyarimana, a Hutu from northern Rwanda, succeeded in stopping the conflicts between Hutu and Tutsi. He banned the Parmehutu and instead created the unity party Mouvement républicain national pour le développement (MRND) tailored to him . In addition to this party and the military as a power base, the new president and his wife Agathe relied on clan and family relationships to secure rule. The decisive posts, especially in the army, were reserved for people from his region of origin in northwest Rwanda. This power group is known as the akazu (little house). Despite the ostensible advocacy of equal opportunities , the official bodies restricted Tutsi's access to education and jobs as well as political power.

At first, the new president's economic policy was successful. However, the economic upturn did not last long. In the mid-1980s, Rwanda got into a state crisis. The country's economy suffered from the rapid drop in the price of coffee - 75 percent of all exports were based on coffee production. The accelerated population growth due to improved medical care and the associated increasing scarcity of land resources exacerbated the situation . The lack of industrial jobs - more than 90 percent of the people lived from agriculture - worsened the economic crisis . Rwanda was forced to accept structural adjustment programs and thus to introduce drastic austerity measures, which among other things resulted in the end of free schooling and free medical care. The devaluation of the national currency also made many imported products more expensive , including food in particular. In view of these circumstances, a feeling of uselessness and lack of prospects was increasingly spreading, especially among unemployed youth and young adults.

Civil war and blocked democratization

The state crisis undermined Habyarimana's authority . It led to the formation of opposition groups that criticized the president's course. These groups, which had support especially in the southern parts of the country, called for democratization. The monopoly of power by Habyarimana's confidants from his home region should come to an end. Foreign countries supported these demands. The western donor countries in particular saw opportunities to overcome undemocratic conditions in Africa after the end of the Cold War . In addition to the demand for democratization, the international appeal to solve the refugee problem, which is now 30 years old, put pressure on the group of people around Habyarimana. Since coming to power, the president had refused to resettle the Tutsi refugees in Rwanda, citing the scarcity of land. It is estimated that around 600,000 Tutsi were living abroad as refugees in the early 1990s. Another factor in the loyalty crisis of the state power was rumors of an imminent, renewed invasion by Tutsi rebels who had grown up in Uganda.

In this situation, Habyarimana announced political reforms in early July 1990 . These plans were initially not implemented because the political conflict turned into a military one - on October 1, 1990, the attack by the Tutsi rebel army of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) began in Uganda . With this campaign, a civil war began , which would not end until the RPF's military victory in July 1994. Habyarimana asked Belgium, France and Zaire for military support. The respective governments complied with this request. The aid provided enabled the Rwandan government army to repel the RPF's first attack. The Belgian troops then left the country, the units of Zaire had to withdraw because they were plundering , but the French military stayed in the country and strengthened Habyarimana's capacities. With French help, the Rwandan army grew from 5,200 men in 1990 to around 35,000 men in 1993. French officers were involved in training the Rwandan army personnel. At the same time, the equipment with war weapons, especially small arms , again mainly with French support, was expanded considerably. Rwanda was the third largest arms importer in the sub-Saharan region from 1992 to 1994 .

The president and his political associates secretly blocked the democratization that they seem to be getting involved in. Journalists who criticized the government were persecuted. The group of people around Habyarimana sponsored radio stations and newspapers that aggressively incited against the opposition and against the Tutsi. Habyarimanas MRND was not ready to share power with the emerging new parties through a coalition government until April 1992. The new parties also included one that was prepared to use radical means to defend the existing Hutu rule. The Coalition pour la Defense de la République (CDR), founded by people close to the President, advocated the expulsion of the Tutsi and from 1992 onwards set up the Impuzamugambi militia. The presidential party MRND organized the Interahamwe in the same year. From October 1990 to April 1994, Tutsi and Hutu opposition activists repeatedly fell victim to violence and massacres, which were declared as revenge for the RPF's military successes. The authorities either encouraged or accepted the violence. The perpetrators were never punished. These human rights violations, in which around 2,000 Tutsi and several Hutu were killed, are considered to be the forerunners of the genocide.

Despite the defeat of the RPF in late October 1990, the rebel army remained a decisive factor in Rwandan politics in the years to come. Paul Kagame enlarged and reorganized the troop. Again and again, military raids and occupations of parts of the country near the Ugandan border succeed. The campaigns and occupations created a massive refugee problem in Rwanda. At the end of the 1980s this number of internally displaced persons was around 80,000, in 1992 it was around 350,000, and after the RPF February offensive of 1993 it rose to around 950,000. Armistice agreements reached in the meantime remained fragile.

In 1992 the RPF succeeded in expanding its zone of influence. She now ruled the northern prefecture of Byumba , which was considered the "bread basket" of Rwanda. This success forced the Rwandan government to join the Arusha peace process from mid-1992 , which promised to bring peace to the country. The negotiations in the Tanzanian city stalled, were interrupted or undermined by fighting that has since resumed. At the core of the negotiations in Arusha was the question of the return of the Rwandan refugees and the repatriation of their previous property, the question of power sharing between the MRND, the other Rwandan parties and the RPF, and the demobilization of the armies and their synthesis a common military apparatus and the establishment of a UN peacekeeping force to secure the results of the negotiations. Although a total of four agreements were signed in Arusha between August 1992 and August 1993 and although the Arusha Peace Treaty was finally initialed on August 4, 1993 , large parts of the MRND and the entire CDR opposed the agreement.

"Hutu Power"

In 1993, the group of people around Habyarimana succeeded in dividing the main opposition parties. Moderate Hutu leaders now faced representatives of the so-called " Hutu power ". They refused any concession to the RPF and thus above all any participation of the Tutsi in political and military power. The intention was to use the "Hutu Power" movement to replace the new loyalties that had arisen towards the parties with a non-partisan commitment to the Hutu cause, which was allegedly threatened by the Tutsi. People close to the president organized this movement with the ultimate goal of establishing a state without Tutsi and without oppositional Hutu. The existence of this rallying movement was announced on October 23, 1993 at a bipartisan meeting in Guitarama .

The rapid increase in the importance of "Hutu power" was significantly influenced by two events. On the one hand, the RPF demonstrated its clear military superiority over government troops in February 1993 when it managed to advance a few kilometers from Kigali . Just the mobilization of more French paratroopers and considerable international pressure on the leadership of the RPF stopped their advance on the Rwandan capital. This attack created fear among the Hutu of the rebels' military potential. On the other hand, Tutsi army members murdered Burundian President Melchior Ndadaye , a Hutu, on October 21, 1993 in Burundi . This event sparked civil war in Burundi. Among the moderate Rwandan Hutu, skepticism about peaceful cooperation with the RPF increased, Hutu hardliners saw in the murder of Ndadaye the evidence of a relentless drive for power by the Tutsi in the entire area of the African Great Lakes. The division of the parties into moderate and extremist wings also made it possible for Habyarimana to delay the implementation of the Arusha peace agreement - the diverging party factions were unable to agree on the staffing of the ministerial posts.

Preparation for genocide

Part of the preparation for the genocide was the development and dissemination of an ideology aimed at the annihilation of the Tutsi and denouncing any coexistence with them as a betrayal of the Hutu. Since 1990, the Kangura newspaper has been issuing requests to do so. The publication of the so-called "Ten Commandments of the Hutu" was one of the most succinct racist statements made by this press organ. Two of these ten commandments were specifically directed against Tutsi women.

Léon Mugesera , a leader of the MRND, was the first leading politician to publicly call for the murder of Tutsi and opposition Hutu in a speech on November 22, 1992. He was then charged with sedition and fled to Canada in 1993.

Even more important was the spread of such messages over the radio - Rwanda had an illiteracy rate of over 40 percent. The power group around President Habyarimana started broadcasting on August 8, 1993 on the propaganda station Radio-Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM). One of the eight presenters on this radio station was Georges Ruggiu , a Belgian who, among other things, attacked Belgium and the Belgian blue helmet contingent. The station quickly enjoyed great popularity because of its laid-back style, interaction through calls from and interviews with listeners, and the apparently appealing selection of music. He also used - although officially a competing medium - resources of the state broadcaster and the presidential palace. To expand the audience, the government distributed radios free of charge to local authorities.

In the years between 1990 and 1994, rhetoric developed against the Tutsi in preparation for the persecution and extermination of this group. This rhetoric shaped the calls for violence in the days of the genocide. One of its central aspects was the technique of twisting. In mirror-image accusations, the extremist Hutu propaganda accused the Tutsi of plotting to annihilate the Hutu. A collective preventive strike of the allegedly threatened is therefore inevitable. In this context, fabricated reports of brutal acts of violence against Hutu played an important role. Another element was the exclusion of the Tutsi from the Rwandan community. Only the majority Hutu people are entitled to rule. Competing claims to power by the Tutsi are undemocratic because they only seek to refeudalize the country. A third hallmark of anti-Tutsi propaganda was the dehumanization of the Tutsi. The propaganda referred to them as cockroaches , snakes , worms , mosquitoes , monkeys, etc., which should be killed. Finally, the verbal attacks on the Tutsi were characterized by the use of the language of agriculture. The Hutu were asked to cut down large trees and bushes - ciphers for Tutsi. Young shoots - meaning children - should by no means be spared. These disguised calls to kill reminded the addressees of their duty to umuganda , to community and charitable work.

Preparations for the attack on the Tutsi also included the development and implementation of programs for the recruitment and training of militias and “civilian self-defense” units. The men involved should be instructed in the fight against the "enemy" by local police officers and former soldiers of the government army. In the early months of 1992, Colonel Théoneste Bagosora , a senior planner in the Defense Ministry, designed a "civilian self-defense" program. Lists of potential militia leaders were drawn up. At the same time, extremist Hutu drew up death lists in 1993 and 1994 that contained the names of Tutsi and opposition Hutu. There were around 1500 names on these lists.

According to these plans, soldiers and political leaders issued large quantities of firearms to the population in 1993 and early 1994. Because this distribution was costly, the power group around Habyarimana decided to buy machetes . The number of these tools imported into Rwanda in the weeks leading up to the genocide was sufficient to equip every third adult Hutu nationwide with them. Machetes had been used and widely used as agricultural tools in Rwanda for decades. A 1984 survey showed that 83 percent of all rural households in Rwanda owned one or more machetes. A January 1994 report by the human rights organization Human Rights Watch revealed that significant quantities of war weapons were also being shipped to Rwanda.

genocide

Initial spark

The assassination of President Habyarimana sparked the genocide. The Dassault Falcon 50 , with which he returned from a conference from Dar es Salaam on April 6, 1994, accompanied by Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira , was launched at around 8:30 p.m. when approaching Kigali airport with shoulder-launched surface-to-air missiles of the type SA-16 shot down. All passengers and the crew were killed.

It has not yet been clarified who was responsible for the downing of the aircraft. It is often suspected that extremist Hutu shot down the machine because they disagreed with the presidential negotiations and the outcome of the Arusha negotiations. The opposite assumption is that the perpetrators came from the ranks of the RPF around Paul Kagame. They were looking for a way not to end the conflict with the Hutu government by compromise, but to finally decide in their favor by means of a civil war.

About 30 minutes after the attack, the killings of opposition Hutu, prominent Tutsi and supporters of the Arusha peace agreement began in Kigali. The perpetrators, above all members of the Presidential Guard, proceeded on the basis of prepared lists, tracked down their victims in their homes and killed them. They were supported by members of other units under the command of extremist Hutu officers and militias. One of the first victims was Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana , who, according to the constitution, held the second highest office in the state after the president. Ghanaian and Belgian members of the UNAMIR who were deployed to protect them could not prevent their murder. They were captured, and the ten Belgian soldiers were subsequently also murdered.

Colonel Bagosora filled the power vacuum at the head of the state on the night of April 6th. He made himself chairman of the so-called crisis team, which consisted exclusively of members of the Rwandan military. The majority of the officers of this body rejected the complete takeover of power by Bagosora. On April 8, Bagosora summoned Hutu extremist politicians and asked them to form a transitional government. Théodore Sindikubwabo was appointed President and Jean Kambanda was appointed Prime Minister .

The international community responded to the outbreak of violence by flying foreigners from Rwanda. French and Belgian soldiers carried out the appropriate evacuation measures . The number of stationed blue helmet soldiers was drastically reduced, triggered by the murder of ten Belgian UNAMIR members.

Regional spread of violence

The violence quickly spread across the country. In the first days of the genocide, relatively few Tutsis fell victim to the acts of violence. One reason for this was the comparatively limited armament of the murderers - the militias and "self-defense units". At the same time, many Tutsi sought refuge in schools, churches, hospitals, sports fields, stadiums and similar places on the instructions of the authorities or voluntarily. They hoped to be able to better defend themselves against the attackers in the crowd. Often the mob - armed with machetes, spears, clubs, clubs of nails, axes, hoes and similar weapons - delayed the attack because they feared their own losses. One possible tactic used by the attackers was to starve the besieged. In many cases, the situation changed from April 13th. On April 12, the state broadcaster Radio Rwanda and RTLM campaigned for an end to the political differences among the Hutu and their joint fight against Tutsi. Better armed units - made up of members of the Presidential Guard, members of the army, reservists and the national police - appeared on the scene and used their weapons against the besieged: firearms (including machine guns ) and hand grenades . Typically, the attackers first asked the Hutu, who had also found protection in the appropriate places, to move away. Tutsi were not allowed to do this. Then, at the beginning of such massacres, the attackers threw a few hand grenades into the crowd of the besieged. This was followed by the use of handguns. Refugees were shot or beaten to death. Militiamen then advanced and killed living victims with cutting weapons . One of these types of crime is the Nyarubuye massacre . According to witnesses, most of the Tutsi refuges were occupied by April 21, 1994. The number of victims is estimated at 250,000 by this time.

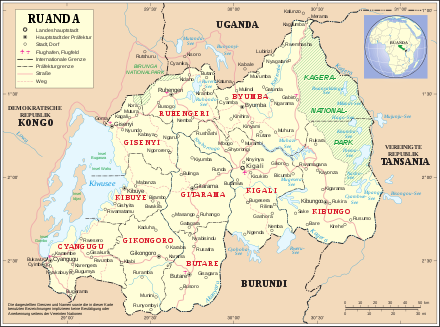

The regional distribution of acts of violence against Tutsi was related to political and historical circumstances. Byumba prefecture, bordering Uganda, was already partially under the control of the RPF at the beginning of the genocide. The rebel army quickly conquered the rest of this area, so that massacres of Tutsi rarely occurred here. Tutsi, who lived in the two northwestern prefectures of Ruhengeri and Gisenyi - the strongholds of the Habyarimana regime - had left these areas before the genocide due to previous threats and violence. That is why these areas were only less affected by massacres. The leadership of the Prefecture in Guitarama was initially in the hands of the Hutu opposition. Only when military units and militias from other parts of the country arrived in this region did extensive massacres of Tutsi begin on April 21, 1994. There was a Tutsi prefect in the Butare region of southern Rwanda . He resisted the intrusion of the militias. On April 18, he was deposed and the mass killings began.

Instructions

Instructions and calls to kill reached the lower ranks of the hierarchies and the population in four ways. In the military, the established structure of command and obedience applied. The transitional government used a second channel, the traditional administrative channels via the prefects, sub-prefects, mayors, local councils and village heads. The administrators in turn urged the civilian population to participate in the killing. This request was often declared as communal community work (umuganda) , which had a long tradition in Rwanda. If the people in question refused to commit themselves to the murder plans, they were deposed, and in some cases even murdered themselves. Party leaders who belonged to the respective extremist Hutu power wings resorted to a third channel of communication. They use the party apparatus to call for the Tutsi to be killed at the local level. A fourth communication structure ran from the command center of “civil self-defense”, which was located near Bagosora, to the local branches of this structure. This line of instruction included the military who, like Bagosora himself, had a political background. The boundary between the local bodies and action groups for “civil self-defense” was not clearly separated from the militias. The hierarchy in the communication lines was not always strictly adhered to. Subordinates who pushed for a more radical course of action against Tutsi could, in case of doubt, prevail against waiting or hesitant superiors. The relationship with the murderous militias also differed from case to case. Some were directed by the military, others by party officials or administrative officials. In many cases, the militias also acted autonomously or, for their part, put members of the administration under pressure not to hesitate to annihilate the Tutsi. In addition to these communication channels, the radio stations Radio Rwanda and above all RTLM played an important role in inciting the Hutu.

Génocidaires

Estimates of the exact number of the perpetrators, also named Génocidaires, vary considerably. Individual studies assume that there are tens of thousands of perpetrators, other authors speak of three million. In many cases, this information is based on speculation. An empirical study published in 2006 estimates the number of perpetrators who committed one or more murders at 175,000 to 210,000. This corresponds to a proportion of about seven to eight percent of the adult Hutu at the time and 14 to 17 percent of the male adult Hutu. In 2000, 110,000 people were detained in Rwanda on charges of genocide; in 1997 the number had peaked at 140,000. In 2006 about 80,000 prisoners were counted.

The overwhelming majority of the perpetrators were men. The proportion of women was around three percent. Pauline Nyiramasuhuko , Minister for Family and Women, was instrumental in the genocide in Rwanda. She gave inciting speeches on the state radio station Radio Rwanda , incited Hutu militias in Butare on refugees, called for the mass rape of Tutsi women and personally selected some of the victims. She is the first woman convicted of genocide and rape as crimes against humanity .

The perpetrators came from all parts of the population. At the top were people with power and influence in the military, in politics and in administration. This was true at the national and local levels. In terms of their number, these elites were of little importance. The majority of the Génocidaires were made up of common Rwandan men. In terms of their education, their occupation, their age and the number of their children, they did not differ from the population average. Analyzes of perpetrators indicate that the most violent among them were young, below-average educated men with few or no children. At the same time, they show that the local initiators of genocide campaigns belonged to the local elite. This group of people was very well integrated into the local community and had an above-average education.

Different motives drove the Génocidaires on. According to the perpetrators, the most important motivation for the involvement of individual Hutu in the genocide was fear . In retrospect, many perpetrators admit that they feared social, material or physical reprisals if they did not participate in murderous acts. The fear of violence by the Tutsi also played a role. The Tutsi were seen as accomplices of the RPF rebels. In the civil war with the rebel army, the aim was to attack and kill the "enemy" in order not to be killed yourself. At the same time, their own acts of violence were to be understood as revenge for the murder of Habyarimana - the RPF and the Tutsi as a whole were considered to be the president's assassins. It was also important that this violence was demanded and approved by the authorities. Killing was considered a duty. Other motives can also be identified, but they were of less importance for the specific willingness of the individual to take part in the genocide. These subordinate motives include, for example, deeply rooted aversions towards the Tutsi and openly racist drives. A number of perpetrators also hoped for material advantages through looting.

Forms of killing

In the first days of the genocide, individual shootings of prominent Tutsi and well-known Hutu opposition members were the order of the day. Another form of killing was used in the first few weeks of the genocide - large crowds of Tutsi were massacred. The perpetrators also used road blockades across the country to control Rwandans on the run. Tutsi and people suspected of being Tutsi or of helping them were murdered at these barricades. Patrols and manhunts complemented this strategy of finding and exterminating victims. In many cases , the killing was preceded by other forms of violence, such as looting, sexual humiliation , rape , mutilation or torture . The perpetrators threw the bodies into rivers or lakes, disposed of them in mass graves , piled them on the side of the road or left them at the crime scene. Some perpetrators gradually severed the body parts of their victims in order to inflict long-lasting and great pain on them. A common torture method against Tutsi was the chopping off of hands and feet. The intention behind this was not only to make escape attempts more difficult, but also the idea of “pruning” tall people. In some cases, victims were forced to kill their own spouses or children. Children were slain in front of their parents. Blood relatives were forced to incest among themselves by perpetrators. People were staked or coerced into cannibalism . Large crowds were often rounded up and burned alive in buildings or killed with hand grenades. Often the victims had to strip naked before killing themselves. This was supposed to humiliate them, and the clothes were still usable for the murderers. In many cases, the burial of Tutsi who had already been killed was prevented. In addition to violating the Rwandan custom of treating the dead with dignity, the corpses were left to be eaten by animals. Cutting weapons were the main weapons used during the genocide. According to the official statistics of the Rwandan government on the 1994 genocide, 37.9 percent of the victims were killed with machetes. The machetes were imported from abroad on a large scale as early as 1993, and were inexpensive and easy to use. 16.8 percent were slain with clubs. An even higher percentage of killings with such weapons has been recorded for Kibuye Province . In this part of the country, 52.8 percent of the genocide victims died from machetes. Another 16.8 percent were murdered with clubs.

Survival strategies and chances of survival

Tutsi survived because they managed to flee the country or because they hid from the murderers inside Rwanda. To do this, they used inaccessible regions such as forest areas or swamps. Holes in the ground, cellars or attics also served as hiding places. In many cases they were helped by Hutu, friends and strangers. In order to survive, many of those in distress paid the perpetrators money several times or submitted to sexual coercion.

The chances of survival of threatened Tutsi and opposition Hutu increased when they were in the vicinity of foreign observers. This was the case, for example, for the Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali. Paul Rusesabagina , the director of this hotel, used his contacts to Rwandan politicians and the military, mobilized the influence of Belgian hotel owners and sent faxes abroad in order to successfully prevent the imminent storming of the hotel complex several times. In this way he saved the lives of 1268 trapped people. UNAMIR headquarters remained a building of the Amahoro Complex in Kigali, which included a large stadium, during the days of the genocide. Thousands fled to this sports facility and survived thanks to the international presence. In the south-west of the country, in the prefecture of Cyangugu , many refugees also gathered at the Kamarampaka stadium to avoid the violence. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) had a base here, as well as in the Nyarushishi camp.

Tutsi had the best chance of survival if the RPF conquered the area in which they were staying. As soon as the rebel army took power in a region, the genocidal actions ceased. Genocidal acts continued for a few more days only in remote areas that were not immediately controlled by RPF troops.

resistance

The genocide was not a joint effort by all Hutu. Individual Hutu tried to evade him or offered resistance. The forms of this nonconformism were manifold. They ranged from fleeing the violence and calling on people to participate, through individual help for threatened Tutsi, to attempts to systematically prevent the start of the genocide in the country or in individual parts of the country.

In the Rwandan military, a group of high-ranking military personnel around Colonel Marcel Gatsinzi and Colonel Léonidas Rusatira initially tried to put a stop to the outbreak of violence and gave the appropriate orders. These instructions, as well as a communiqué drawn up by them on April 13, 1994, had no effect, however, because the armed forces were already predominantly in the hands of the extremist Hutu officers. The military who opposed the genocide were threatened with life and limb attacks and their commands were circumvented. Gatsinzi and Rusatira, for example, quickly lost their posts to extremist Hutu military.

Influential people in the administration also opposed the beginning of the genocide. The prefects of Guitarama and Butare, Fidèle Uwizeye and Jean-Baptiste Habyalimana , respectively , succeeded in largely preventing violence against Tutsi in the first few days by working with reliable mayors and other administrative staff from their prefectures to prevent militias from other parts of the country from entering and punished the first acts of violence against Tutsi - such as looting or individual murders - immediately. After the government fled from Kigali to Guitarama on April 12, 1994, the resistance to genocide collapsed in Guitarama, as the government was accompanied by armed units such as the Presidential Guard and the Interahamwe. These associations put the local administration under pressure and incited the population to commit genocide, in which they took a leading role. After the forces prepared for genocide had prevailed and attempts to resist were unsuccessful, Uwizeye fled. Jean-Baptiste Habyalimana, the only prefect from the ranks of the Tutsi, used his position in Butare until mid-April to take action against attempts to inflict violence on the Tutsi in this southern province. He relied on loyal national police officers and mayors who faced increasing power of military officers, militiamen and Hutu refugees from Burundi who advocated genocide. On April 17, Habyalimana was removed from office, later imprisoned and executed .

Tutsi resistance is guaranteed in many places in Rwanda. Occasionally, those threatened developed targeted strategies to be able to ward off the attacks better or to increase the probability of survival in the event of mass escapes. One defense strategy was called kiwunga (to merge). The attacked lay down on the floor. Only when the attackers were among them did the Tutsi jump up to face the perpetrators in hand-to-hand combat . In this situation, they shied away from the use of handguns or grenades because they feared casualties from being shot by their own people. In some places attacked Tutsi divided into groups and fled at different times and in different directions. In Bisesero near Kibuye, Tutsi defended themselves for a long time by taking refuge on a wooded and stony ridge. There they hid and threw stones at the attackers. The defense was coordinated; Tutsi who refused to take part in the defense were beaten by others forcing them to do so. It was only when army units reinforced the attackers that the resistance was broken and tens of thousands of Tutsi were murdered, only about 1500 Tutsi survived the massacre.

Role of Twa

Genocide studies rarely deal with the role of the TWA . This is mainly due to the small proportion of the Twa in the total population of Rwanda. It is less than one percent, around 30,000 people were counted to the Twa ethnic group before April 1994. Added to this is their low social status as an indigenous people .

It is estimated that around a third of the Twa perished during the genocide in Rwanda and another third fled abroad. The Twa were not only victims, members of this group also joined the militia. However, the extent of their involvement in the genocide is unknown.

Another civil war

The shooting down of the presidential machine was the signal for the beginning of the genocide and at the same time the occasion for the renewed outbreak of civil war between the government troops and the rebel army RPF. According to the Arusha Agreement, a battalion of 600 RPF soldiers was billeted in the National Council building in Kigali. Before April 6, 1994, the rebels secretly reinforced this unit to around 1,000 men. The battalion was taken under fire by government troops in the first hours after the attack on Habyarimana, but held the position until further RPF units marched into the Rwandan capital on April 11, 1994.

Under the military leadership of Paul Kagame, the rebel army launched an offensive from its headquarters in northern Rwanda. In April 1994, the rebels' military action led to the rapid conquest of the Byumba and Kibungo prefectures. Also in April, the rebels began attacking Kigali from the north and east. The pressure of this military offensive forced the government on April 12 to flee the capital to Guitarama, the next major city west of Kigali. Thousands of civilians joined this escape. Army units loyal to the government remained in Kigali while the rebel army attempted to encircle and besiege the capital . In May, RPF units brought in from Kigali and Kibungo Prefecture attacked Guitarama. On June 9, 1994, they began to invade the city. After this success they advanced south and captured the Butare prefecture bordering Burundi by the beginning of July. On July 4th, the government troops withdrew from Kigali to the west, again accompanied by thousands of civilians, and the capital fell to the rebels. The RPF had already attempted to advance on Ruhengeri in April. This advance stalled, mainly because the main rebel forces were used in the Battle of Kigali and for military operations in the east of the country. It was not until July, after the military successes in the center and south of the country, that the RPF was victorious in northern Rwanda and took Ruhengeri on July 14, 1994 and Gisenyi three days later. The advance of the rebels in the south-west of the country was initially stopped by French intervention troops, who set up a security zone in this part of the country.

The RPF's victory ended civil war and genocide. Many perpetrators and members of the government fled abroad. The RPF won despite being outnumbered by government forces. For the beginning of April the troop strength of the RPF is given as 20,000 to 25,000 men. The number of their opponents - government soldiers, members of the presidential guard, national police and militias - is estimated at 55,000 to 70,000 men. The RPF made up for its quantitative disadvantage with its above-average military discipline and efficiency. In addition, the Hutu government lacked military support from France, which at the beginning of 1993 had again averted the victory of the RPF. As early as 1993, studies by the Tanzanian and French military intelligence services concluded that the RPF was clearly superior to the government units.

The goal of the RPF's military efforts was to defeat government forces, not just to save the Tutsi. The Canadian UN General Roméo Dallaire asked about the priorities of the RPF in his report on the genocide in Rwanda . In his view, it is not impossible that Paul Kagame accepted genocide in order to come to power.

Violence by the RPF

The RPF killed tens of thousands of people in combat and then while attempting to control the conquered area. Massacre in military conflicts and at public meetings after the end of hostilities, was legal and arbitrary executions came to an extent before, which suggests knowledge and acquiescence by the higher ranks of the RPF, if not on planning. It was only in August and especially in September that these human rights violations subsided as a result of considerable international pressure. The RPF prevented UN officials, human rights organizations and journalists from investigating evidence of human rights violations by rebels.

Robert Gersony, a senior staff member of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), collected extensive information from the beginning of August to the beginning of September 1994, which underlined the systematic nature of the serious human rights violations. According to his report, approximately 25,000 to 45,000 people have died as a result of human rights abuses by RPF units. The UNHCR later denied the existence of the Gersony report . Critics of this UNHCR position claim that this happened because the UN, the United States and the Rwandan government agreed not to publicly attach little weight to these RPF offenses in order not to snub the new Rwandan government.

International reactions

A key element of the Arusha Agreement was the establishment of UN peacekeeping forces in Rwanda. The Canadian general Roméo Dallaire was in command of UNAMIR from October 1993 , which faced considerable problems from the start. RTLM assumed the Belgian contingent of UNAMIR to be on the side of the rebels. The majority of the blue helmet troops, which at the end of March 1994 reached a strength of around 2500 men, were soldiers from Ghana and Bangladesh . The military capabilities and resources of the Bengalis in particular often proved to be inadequate in the coming months. The troop's financing was unsecured for many months. Another difficulty lay in the mandate. UNAMIR had a mandate under Chapter VI of the United Nations Charter . Only the promotion of peace, a so-called peace mission , was possible, not the enforcement of peace against one or more warring parties - such an approach would have required a mandate under Chapter VII of the Charter. The UNAMIR soldiers were only allowed to use weapons in extreme emergencies for self-defense.

In January 1994, Dallaire became aware of secret weapons stores, death lists, planned attacks on the Belgian UNAMIR soldiers as well as the targeted torpedoing of the Arusha peace process and planned mass killings in the following three months. He informed his superiors at UN headquarters by fax on January 11th. At that time, the later Secretary General of the United Nations and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Kofi Annan, was responsible for UN missions abroad . Dallaire's office expressly instructed Dallaire to interpret the Chapter VI mandate narrowly and not to dig up the weapons caches, but to seek talks with President Habyarimana. Further warnings from the UNAMIR commander and his requests for a strengthening of the mandate and better equipment for UNAMIR also had no effect. Dallaire later accused Kofi Annan of complicity in the genocide. A May 3, 1998 article in The New Yorker suggests that Annan withheld repeated requests for assistance and reports from Rwanda about the impending genocide and not passed them on to the UN Security Council.

After the outbreak of violence, particularly in response to the killing of the ten Belgian UNAMIR soldiers, the UN reduced its blue helmet troops from around 2,500 to 270 soldiers. According to Dallaire, the complete withdrawal of the Belgians in particular was a severe blow to UNAMIR. Because some of the blue helmets could not be flown out, however, 540 men remained on site. Rwandans who had sought protection near blue helmet troops fell into the hands of their murderers after they withdrew. The best-known example of this is the massacre at the École Technique Officielle in Kigali. Immediately after 90 Belgians withdrew, militiamen and members of the Rwandan army killed around 2,000 people who had sought refuge in this school. Critics of the UN withdrawal see in this on the one hand the removal of the last protection for the oppressed, on the other hand a license for the perpetrators to continue the genocide.

France and Belgium, with the support of Italy and the United States, organized the Operation Amaryllis evacuation operation . Belgian and French elite troops brought about 4,000 foreigners to safety from April 8-14, 1994, but not Rwandans who were employed by foreign institutions and were already threatened. German evacuation capacities were not available. This was seen as the main reason for the establishment of the Special Forces Command .

Despite the increasing density of information on the extent of the violence, the American government consciously avoided speaking of genocide. If the events had been described in this way, the international community would have been obliged to act in accordance with the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide . Instead, representatives of the US government spoke of "chaos" or possible "genocidal acts". The choice of this term was related to the experiences made only a few months earlier during UNOSOM II , which failed as an armed humanitarian operation in Somalia at the beginning of October 1993. After 18 US soldiers had been killed on this mission and the images of the desecration of their corpses had been seen on television worldwide, the US was not ready to start another humanitarian mission in black Africa . This was reinforced by a Presidential Directive (PDD 25) of 1993. Rwanda was also considered a country of no strategic value.

The then Secretary General of the United Nations, Boutros Boutros-Ghali , also chose indistinct wording. On April 20, 1994, he spoke of a people who "got into dire circumstances". At that time, human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and the Fédération Internationale des Ligues des Droits de l'Homme were already explicitly calling the events genocide.

Coincidentally, during the weeks of the genocide, Rwanda had a seat on the United Nations Security Council as a non-permanent member . The Rwandan government was thus informed first-hand about the discussions and moods in this body. On May 16, 1994, representatives of the Rwandan government attended a meeting of the Security Council. Of the 14 remaining members, only a minority criticized the Rwandan representatives for the excessive acts of violence. The government responsible for the genocide was able to conclude from this behavior that the Security Council did not have clear information and would not make up its mind to speak clearly.

From the end of April to mid-May 1994, the mood changed after more and more television reports showed refugees fleeing en masse from Rwanda to the neighboring country to the west of Zaire. This stream of refugees consisted of Hutu, who backed away from the advancing RPF units. The fear of retribution, which was massively fueled by the radio stations, drove them to do so. At the same time, Hutu militias forced these refugees to serve as human shields . On May 17, the UN Security Council decided to deploy UNAMIR II. This force should comprise 5,500 men and be equipped with a more robust mandate than its predecessor, which allowed the military protection of threatened civilians. Despite this decision, the formation of the required troops and the provision of the necessary military material was delayed. When the RPF won the civil war in mid-July, there were still roughly the same number of blue helmet soldiers in Rwanda as immediately after the troop reduction.

With this in mind, France took the initiative and headed Opération Turquoise . This humanitarian intervention was based on Chapter VII of the UN Charter and, from June 24, 1994, led to the creation and maintenance of a security zone in south-west Rwanda. Hutu refugees clustered in this area, which made up about a fifth of Rwanda. The declared purpose was to protect civilians within this zone and to promote the distribution of aid through aid organizations . The operation, while keeping many civilians safe, met with criticism from the start. The RPF saw in this measure the continuation of France's attempt to support the old government of Rwanda and to thwart the victory of the RPF. This view was promoted by the fact that extremist Hutu euphorically welcomed the French invasion and tried to encourage them to fight the rebels. The intervention force did not disarm the Hutu militias and did not prevent perpetrators and government officials from fleeing abroad. This also encouraged criticism of France's politics. On August 21, 1994, the French surrendered the zone to the now strengthened UNAMIR II.

In 2010, French President Nicolas Sarkozy admitted serious mistakes made by his country in view of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. "There was a form of blindness, we did not see the genocide dimension" .

In 2014, German media reported that German authorities might be aware of the preparations for the genocide. A Bundeswehr officer , then a member of a military adviser mission, warned the Federal Ministry of Defense of possible massacres. Then nothing happened. The German ambassador to Rwanda also ignored information about the danger of an escalation of violence.

follow

Refugee crisis

The genocide destabilized the entire African Great Lakes region. More than two million Rwandans fled the country. In response to these flows of refugees, the spread of epidemics and the very high mortality rate in the refugee camps , a comprehensive international relief effort was launched. The focus was on the camps in Eastern Zaire, near the city of Goma . Most of the refugees lived here. In these border camps, extremist Hutu quickly took power. They developed the camps into bases for the reconquest of Rwanda without this abuse by aid organizations or UN agencies having actually been contradicted. Extremist politicians, former administrative employees, soldiers and militia officers forced the civilian refugee population to cover up this abuse. The continued political incitement against Tutsi and resistance Hutu, the control of the distribution of aid, the procurement of weapons for the re-entry into Rwanda, the recruitment of new fighters from the ranks of the refugees and the establishment of military training camps were part of everyday life in these camps. After a series of acts of sabotage in Rwanda from these camps as well as after the massive threat to the Banyamulenge , an ethnic group close to the Tutsi who had lived in eastern Zaire for generations, these camps were turned into a joint action by associations of the Banyamulenge, the new Rwandan, from the end of 1996 Army and military units from Uganda disbanded. About 500,000 refugees went back to Rwanda, thus escaping the influence of the extremist Hutu. The militias and the groups of refugees they dominated, around 300,000 to 350,000 people in total, moved further into the interior of Zaire. These events also marked the beginning of the first Congo War . Around 500,000 refugees from Tanzania returned to Rwanda at the same time.

The situation in the eastern Congolese provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu has been unstable for years. At the end of 2007, around 600,000 to 800,000 people were fleeing the clashes of the Forces Démocratiques de la Liberation du Rwanda , an approximately 6,000-strong force from Génocidaires and other Hutu on the one hand, and a 4,000 to 6,000-strong Tutsi combat group by Laurent Nkunda , which is allegedly backed by Rwanda, on the other side.

Rape victim

The exact number of women and girls raped during the Rwandan genocide is unknown. According to UNICEF , the number of girls and women raped is estimated at 250,000 to 500,000. The women affected often suffer from social ostracism , because in Rwanda such acts are also considered to be the personal disgrace of the victims. Many women who have been raped have become mothers as a result of the sexual violence - an estimated 2,000 to 5,000 cases. A high percentage of those raped are HIV- positive. Treatment of raped women with AIDS often fails because of the cost of the appropriate medication. People interned as a result of the genocide, however, are treated because appropriate resources are made available.

Households without adults

In 1999, there were an estimated 45,000 to 60,000 households in Rwanda headed by minors. Around 300,000 children lived in such households, almost 90 percent of which were run by girls who did not have a regular income. The children received little help, but were largely left to their own devices without being able to ensure that their basic needs were met . The spread of AIDS, spurred by the rapes during the genocide, orphaned 160,000 children . An increase in this number is to be expected. For Kigali alone, the proportion of pregnant women infected with HIV is estimated at 30 percent. Immediately after the genocide, the proportion of women in Rwanda was around 70 percent due to the murder, flight or arrest of men. Under the aspect of the higher quota of women, the genocide is therefore also referred to as gendercide in special publications . In certain areas of Rwanda, this situation led to the practice of male sharing ( kwinjira ), which, in addition to possible personal conflicts, also harbors new dangers in relation to the spread of AIDS.

Young perpetrators

A peculiarity of the genocide in Rwanda is the large number of young perpetrators. Often they were traumatized by their own actions. Around 5,000 young people were imprisoned. Those under fourteen at the time of the events were released until 2001. The lack of education, the years of imprisonment during adolescence and the loss of the role model function of the parents' generation lead to a pronounced lack of perspective and disorientation in this group. Returning these children to their families is often problematic. Often they are turned away for economic reasons or for fear of repression.

Religion and genocide

Until 1994, Rwanda was considered the most strongly Catholic country in Africa. Before April 1994, 68 percent of the population belonged to the Catholic Church , 18 percent belonged to Protestant churches . About one percent were Muslim . All Christian communities with the exception of Jehovah's Witnesses are alleged to have been involved in the genocide. The Catholic Church is particularly accused of indirect joint responsibility. She had close ties to the Habyarimana power group.

The allegations include the majority of the clergy remaining silent about the genocide, but also promoting and calling for criminal offenses and in some cases direct perpetration. The Rwandan Tribunal found the Catholic priest Athanase Seromba guilty of aiding and abetting genocide and crimes against humanity. He is said to have lured 2000 people into the church he administers. Instead of giving them refuge, however, he removed religious symbols and gave the order to tear down the building, which had been declared secular, with a bulldozer. The survivors were then killed by Hutu soldiers. Churches were often the scene of massacres without church representatives always having a leading role. In Rwanda alone, however, by 2006 more than twenty clergymen had been charged for their involvement in the genocide. On the other hand, a number of church representatives protected the persecuted and countered the violence on the ground. At the same time, several hundred clerics, especially Tutsi and priests critical of the government, were among the victims of the acts of violence.

Participation in the genocide led to a loss of confidence in the established churches, many people leaving the church and an increased focus on free churches and Islam. The churches concerned have hardly come to grips with the silence of the clergy and the active participation of some church representatives in genocide crimes. However, there are confessions of guilt or apologies from some churches, such as the Protestant churches in Rwanda. In 1996 Pope John Paul II rejected the Catholic Church's responsibility for the genocide. The guilt lies solely with individual perpetrators from among the believers. Pope Francis surrendered to ask for forgiveness in 2017.

During the genocide, it was noticeable that Muslims protected Tutsi and Hutu who were under threat. Widespread participation in the acts of violence is not known, but there are also examples of Muslims who became perpetrators. At the same time, as a group, they were not the target of the violence. Many Rwandans did not consider them to be residents of the country, but rather a special group that did not derive their identity from the reference to their geographical home, but from the community of Muslims. The rescue of existentially threatened people and the extensive refusal to take part in the genocide have sustainably improved the appreciation of Muslims in post-genocidal Rwanda. They are considered an example of the non-ethnic, Rwandan identity to be striven for. The proportion of Muslims has risen sharply since mid-1994 and in 2006 was around 8.2 percent. It also plays a role to be able to avoid possible future outbreaks of violence by converting to Islam. Leading Muslims in Rwanda see it as their job to contribute to the reconciliation of Tutsi and Hutu, and call this duty " jihad " in Rwanda. Islamic fundamentalism is not observed in Rwanda.

Legal processing

The legal processing of the genocide takes place on three levels. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) is bringing charges against the exclusive circle of high-ranking planners and organizers of the genocide. This ad hoc court is based on a decision by the Security Council and is conducting the relevant processes in Arusha, Tanzania. Critics accuse the criminal court of inefficiency. Between November 1995 and the beginning of April 2014, he pronounced judgments in 75 cases, twelve of which were acquittals. 16 of the 75 cases were on appeal. In addition, ten cases were referred to national courts, two defendants died before the end of the trial, and two charges were dropped. Critics complain that the number of processes is relatively low despite an average annual budget of 100 million US dollars and over 800 employees. In addition to this criticism of a lack of efficiency, there is also the accusation of inadequate public relations work. Hardly anyone in Rwanda or abroad is interested in the Arusha trials. The court is credited with not only indicting individuals for genocidal crimes, but also convicting them, that Jean Kambanda, head of state during the genocide, formulated a comprehensive admission of guilt in his trial and that rape or sexual mutilation as a crime against humanity and as a trend-setting current judgment against Jean Paul Akayesu recognized as acts of genocide. The International Residual Mechanism for the ad hoc criminal courts has been functioning as the joint successor institution of the ICTR and the International Criminal Court for the Former Yugoslavia since July 2012 .

Most of the perpetrators are left to Rwanda's national jurisdiction, the second tier of legal treatment of the genocide. However, due to the large number of cases, this is not able to ensure timely court hearings. Few judges survived the genocide. Despite internationally funded training programs and activities to rebuild the justice system, the efficiency and independence of the national courts remained inadequate. By 2004 there were around 10,000 judgments in the ordinary Rwandan courts, 20 percent of which were acquittals and 10 percent were death sentences.

2005 to 2012. Therefore, genocide trials found nationwide in so-called Gacaca -Gerichten instead. The central aim of creating this third level was to speed up the genocide processes and to deal with their large numbers. Socially recognized, elected lay judges - their total number was around 260,000 - judged here in public meetings that followed the rules laid down by law and at which at least 100 adults had to be present. There were around 10,000 such dishes in Rwanda. In addition to the judicial function, the gacacas should also fulfill social tasks. Perpetrators and victims should reconstruct what happened, the suffering of the victims should be made publicly visible in the negotiations. Hutu and Tutsi were to be reconciled with each other whenever possible. The initial euphoria gave way to national disillusionment. Often the necessary quorum of 100 adults in attendance did not come together because there was no interest in the proceedings. Often the suffering of the Tutsi was not recognized by the Hutu, Hutu felt collectively denounced, compensation for victims could not be paid, threats against witnesses could not be effectively prevented, many victims could not remember the exact course of the crime, which was a reliable assignment of acts of violence against individuals often made impossible. Skeptical voices feared that many imprisoned alleged perpetrators would not be tried because of amnesties . In addition, an increase in the number of processes was expected. Instead of 80,000 trials, 1,000,000 trials were sometimes expected because the threshold for indictments fell. Often denunciation , a mere suspicion or the redirection of charges to other people who have not yet been considered by the criminal justice system are sufficient. Against the background of such estimates, critics of the Gacaca jurisdiction established a failure of any attempt at reconciliation, if not an attempt by the rulers in Rwanda to collectively criminalize the Hutu through Gacacas and in this way to consolidate the rule of the Tutsi. Despite these shortcomings, international observers did not plead for an end to the gacaca jurisdiction, but for its gradual improvement. In June 2012, the gacaca courts officially ceased operations.

The international Mpanga prison, which opened in 2006 and has 8,000 prison places, detained perpetrators of the genocide in Rwanda, as well as people convicted by the Special Court for Sierra Leone . The prisoners from Rwanda were housed in a separate wing.

Ephraim Nkezabera, the so-called "banker of the genocide" was arrested in 2004 in Brussels . In addition to various war crimes, the former bank director was also accused of having financed and equipped the Interahamwe militias and of having been involved in the financing of the Radio-Télévision Libre des Mille Collines station . In 2009 he was sentenced to 30 years in prison by a Belgian court for war crimes.

In May 2020, the French police arrested Félicien Kabuga , who was living under a false identity in Asnières-sur-Seine and wanted by international arrest warrant . The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda had charged him with setting up the Interahamwe militia. Kabuga is described by the media as the financier of genocide.

Memorials

In many parts of the country there have been memorials to commemorate the genocide since 1995 . During the national commemoration week, one week in April, new places of remembrance are inaugurated and existing ones are used for collective mourning and memorial events. The Rwandan state is concentrating its work on seven such institutions. With the help of foreign partners, they are developed and maintained as places of mourning, remembrance, reflection, exchange, learning and prevention . The central museum of this kind, the Kigali Genocide Memorial , opened in 2004 in the Rwandan capital. The communal graves of this facility house the remains of around 250,000 people. Part of the facility is the national genocide documentation center. In addition to the seven central memorials, including the Murambi Genocide Memorial Center , there are around 200 regional and local ones. They are in places where large groups of people were murdered during the genocide.

A political and discursive intention is pursued through the design of the memorials . In many cases, hundreds of bones are deliberately exposed. They serve as material evidence of the extensive acts of violence. The denial and trivialization of the genocide should be made more difficult in this way.

The public presentation of the remains aroused criticism outside, and especially within, Rwanda. Such a practice violates Rwandan traditions in dealing with the dead, which provide for the remains of the deceased to be buried as quickly and inconspicuously as possible. The victims buried in memorials are exclusively Tutsi, Hutu are not buried there. This is a discrimination against groups of victims. Many Hutu are annoyed that they are hardly perceived as victims here, even though they have been damaged by civil war, refugee misery and acts of revenge. The rulers are also assumed to have instrumentalized the memory of the genocide in raising funds for development cooperation . Through the establishment and maintenance of genocide memorials, the guilty conscience about the passive attitude of the world community between April and July 1994 was maintained in international donor institutions.

Reconciliation policy

The government of Rwanda, led by the RPF, tried a policy of reconstruction and reconciliation after the end of the genocide. This policy, largely shaped by Paul Kagame, was influenced by the defense of the threat posed by Hutu extremists who wanted to destabilize and recapture Rwanda from Zaire. This threat and the experience of genocide led to the emergence of a pronounced need for security, which has a major impact on the rejection of domestic demands for democratization. International observers criticize significant shortcomings when it comes to the protection of human rights and freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

Publicly speaking in Rwanda only Banyarwanda , Rwandans, no longer Tutsi, Twa or Hutu. The government has abolished such entries in the personal papers. Anyone who uses ethnic terms to argue with reference to the present can be charged with “divisionism”, that is, the deliberate division of the population. At the same time, surveys show that the population thinks in ethnic categories and uses them to differentiate between people.

Many Rwandans do not take part in political discussions because they fear they will be punished for being involved in genocide if they do not express their opinion. Participation offers - such as the discussion of the constitution, the planning of the Gacaca jurisdiction or involvement in the reconciliation forums organized nationwide by the National Commission for Unity and Reconciliation since 1999 - are therefore only accepted to a limited extent. The legitimacy of the government in the international community, with donor institutions and parts of the population sank due to the unmistakable dominance of the RPF in the political arena and due to the interventions in the Congo.

Society's dividing lines between Hutu and Tutsi have not been overcome. The Twa continue to lead a social and political shadowy existence and are barely able to articulate their interests. There are also dividing lines between Tutsi who survived the genocide in Rwanda and Tutsi who returned from abroad after mid-1994. So far (as of 2020) these faults could not be covered by newly introduced national symbols - including the anthem and the flag - and a reorganization of the administrative structure of Rwanda .

Investigations and lawsuits against RPF representatives

Repeated investigations and lawsuits have been launched against Paul Kagame and other RPF executives because there is suspicion that this group of people was involved in leading crimes. At the ICTR, the Swiss Carla Del Ponte initiated investigations into RPF members in 2000 who are suspected of having committed serious crimes during and after the civil war. This investigation, which has not been completed, has met with displeasure from the Rwandan government. This is said to have contributed to the replacement of Del Pontes as chief prosecutor of the ICTR in 2003. The French investigating judge Jean-Louis Bruguière brought charges against the Rwandan president and nine other people. You are held responsible for the shooting down of the presidential plane on April 6, 1994, and thus for the murder of the crew and all occupants of the aircraft. The charges resulted in the severance of diplomatic relations between France and Rwanda. In February 2008, international arrest warrants were issued against 40 RPF members in Spain. The wanted are charged with serious crimes in Rwanda and Zaire. Kagame is one of the suspects. The Rwandan government spoke of a campaign staged by Hutu extremists. In November 2008, relations between Germany and Rwanda fell into a crisis. German authorities had previously arrested Rose Kabuye , a confidante of Kagame and a former high-ranking member of the RPF, and extradited to France. The French authorities accuse her of participating in the shooting down of the Juvénal Habyarimana machine.

France's role in genocide

According to the Rwandan government, a report has been issued that assigns twenty French military personnel and twelve politicians, including Édouard Balladur , Alain Juppé and François Mitterrand , a leading role in carrying out the massacres. Rwanda's reaction in August 2008 was the threat of issuing international arrest warrants against high-ranking French officials. In an initial reaction from the French side, all allegations were firmly rejected.

France had maintained close contacts with the government since the Hutu Revolution and viewed Rwanda as an essential part of the Francophonie and thus its own sphere of influence in Africa. The attacks by the RPF were perceived as "Anglophone" aggression and threat, as an attempt to take over Rwanda and extricate it from the French sphere of influence. In this context, France was also accused of having created a staff for strategy and psychological warfare within the Rwandan army with the légion présidentielle , which only acted on Mitterrand's instructions. In addition, after the genocide began, numerous French military personnel remained in the country. They were integrated into Rwandan Hutu army units that were actively involved in the genocide. According to a statement by the Rwandan Ministry of Justice, French soldiers are also said to have actively participated in the massacres as part of Opération Turquoise. In April 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that he had instructed a commission of historians to inspect “all French archives relating to Rwanda between 1990 and 1994” and to prepare a report on the role of France. This commission of historians stressed in the final report published in March 2021 that France bears a “grave and overwhelming responsibility” for the genocide. Historians rated France's actions as “blindness” and “failure” because it did not prevent the genocide. Under the then President François Mitterrand , the country “unconditionally” supported the “racist, corrupt and violent” Juvénal Habyarimana regime. Mitterrand maintained close personal relationships with Habyarimana and received him several times in Paris. The commission could not prove a "complicity" of France in the killings.

President Macron said on a state visit to Rwanda in May 2021 that nothing could excuse genocide . He hope to be forgiven .

Interpretations and Debates

The events in Rwanda between April and July 1994 were initially described almost without exception as a "tribal feud" by politicians and journalists. Ancient hatred broke out with a suddenness and violence that left the viewer shaking their heads.

Human rights activists and scientists interpreted events quite differently relatively quickly. The violence was modern, systematic and deliberate. A certain group of extremist Hutu politicians planned them and directed them against a racially defined minority. For the release of violence, this group used modern ethnic categories manipulated in the colonial era as well as a modern ideology of ethnic nationalism . These politicians also used the state structures of Rwanda to implement their policies. The country has not experienced a relapse into tribalism , but rather a modern genocide.

There is no consensus on the causes of the violence in the literature on the Rwandan genocide. Three major explanatory models can be distinguished. The first regards genocide as a measure taken by a group whose political power was challenged - the “little house” (akazu) - to avert the impending loss of power. The genocide thus appears as manipulation by an elite. A second explanation is based on Rwanda's natural resources, which were becoming increasingly scarce before the genocide. Land scarcity, largely a lack of livelihoods outside of agriculture, at the same time high birth rates and ultimately “ overpopulation ” were the decisive driving forces behind the genocidal violence. A third explanatory model focuses on assumptions about the cultural peculiarities of Rwanda and supposedly characteristic social-psychological properties of its residents. Rwandans were used to following orders without question. A downright tendency to obedience is widespread. This characteristic trait made it possible to involve hundreds of thousands as perpetrators.

Many studies deal with the responsibility of the international community for genocide. Most of the authors sharply criticize the actions of the main international actors. The early withdrawal of UNAMIR and the weeks of inactivity of the key international actors would result in the global community sharing responsibility for the genocide. Opportunities for a quick end were not used, although the extent of the violence was known early on.