Special Forces Command

|

Special Forces Command |

|

|---|---|

Association badge |

|

| Lineup | September 20, 1996 |

| Country |

|

| Armed forces |

|

| Branch of service | Special forces |

| strength | 1400 soldiers |

| Insinuation |

|

| Location |

|

| motto | unofficial: facit omnia voluntas ( Latin , 'the will decides') |

| Awards | US Navy Presidential Unit Citation for KSK units of Task Force K-Bar |

| Web presence | KSK |

| commander | |

| commander | Brigadier General Ansgar Meyer |

| insignia | |

| Beret badge |

|

The Special Forces Command ( KSK ) is a special military unit and large unit at the brigade level of the Bundeswehr with the focus on special operations and command warfare , reconnaissance , counter-terrorism , rescue, evacuation and recovery as well as military advice . The KSK is subordinate to the Rapid Forces Division (DSK) and is stationed in the Graf Zeppelin barracks in Calw , Württemberg .

The British Special Air Service (SAS), the US Special Operations Forces and the GSG 9 of the Federal Police served as models for setting up and aligning the KSK .

The association has since its formation, among others, for the prosecution of war criminals in the former Yugoslavia and the war in Afghanistan since 2001 used. A military hostage rescue by the KSK never took place (as of June 2020).

The association and its operations are subject to special military secrecy . Even after the missions were completed, no information about successes or losses was published for a long time. This has already led to criticism from members of the Bundestag as well as in the press on several occasions .

The KSK repeatedly made headlines due to right-wing extremism incidents, particularly towards the end of the 2010s , so that it was reformed in 2020.

story

background

During the Cold War , the Bundeswehr served the purpose of territorial defense in accordance with its self-image and its primary focus . It also had a considerable number of paratroopers , but they were planned as a quick deployment reserve and not as an "offensive element" on foreign soil. Their training and orientation were based on classic war scenarios that were based on long front lines. The jump operation into the enemy hinterland was part of the operational conception, but was more of an exception option. The paratrooper troops were not primarily intended for commando companies with a coup d'état or ambush in a hunt . This resulted in what the versatility of this branch of service was concerned, a reverse trend compared to their use in WWII . Special units were already the frogmen of the Navy and the Fernspäher the army . However, these were numerically very small units with specific tasks such as underwater combat and long-range reconnaissance.

With German reunification in 1990 and the end of the Cold War, the security policy framework in the Federal Republic also changed; large standing armies and armored forces were no longer needed and, accordingly, were massively disarmed in Europe. A first reaction to the new political situation was the Army Structure V (1990-1992) , a comprehensive structural reform to reduce the size of the armed forces, which became necessary after the unification of the Bundeswehr and National People's Army (NVA) (including the use of synergies and the settlement of the NVA). Among other things, it stipulated that the paratrooper companies B1 (command) were to be set up, one each in airborne brigades 25, 26 and 27. For the first time, they were specially trained for command combat, the attack and coup-like combat of operationally valuable targets in the enemy hinterland. At the same time, these command companies were also trained in "rescue and liberation", ie the ability to solve hostage situations, which made a fundamentally offensive operational component of the paratroopers available for the first time.

This restructuring was finally defined in the White Paper of 1994, which describes the necessary adaptation of the Bundeswehr to the new tasks, including the development of crisis reaction forces .

The specific reason for the establishment of the KSK was the fact that in 1994, during the genocide in Rwanda, German citizens had to be evacuated by Belgian para-commandos . The decision that this task should be carried out by special forces of the former colonial power Belgium was made in advance by mutual agreement between the NATO partners. The federal government also refused to intervene because, in its view, neither the GSG 9 nor the command companies of the paratroopers were trained to operate in a guerrilla war situation and there was also a lack of the necessary technical means for delivery and execution.

As a result of this crisis, NATO evacuation plans and regional assignments of responsibility defined which country should be the lead nation in which region in the event of future comparable crises . At the same time, secret deployment plans were drawn up between the NATO partners. In accordance with these additions to the valid NATO doctrine, special forces were to be kept available for military operations, due to the special nature and political significance of the order, due to the special features of the task fulfillment - possibly also concealed and associated with high risk - as well as the importance of the objectives of the operations policies and procedures other than traditional force deployments should be followed. This involvement in planning and NATO doctrine increased the pressure of the allies on Germany to build up its own capacities for this area of responsibility. The allies apparently expected Germany to be willing and able to find an independent solution in a situation similar to that in Rwanda, in which twelve Belgian soldiers died. In an interview with author Sören Sünkler (see literature list), the commander of the Belgian task force confirmed the lack of understanding for the German attitude at the time.

The decisive factor was the Federal Constitutional Court ruling of July 12, 1994, the so-called out-of-area ruling , which bindingly stated that humanitarian and military operations by the Bundeswehr were also permitted outside of NATO territory. A prior constitutional approval of the German Bundestag was stipulated as a prerequisite for such an operation, for which a simple majority is sufficient. This new legal room for maneuver paved the way for planning in the Federal Ministry of Defense at a time when Germany was still looking for its new role in world politics, together with the increasingly asked question abroad why Germany had not carried out a rescue itself. and provision of immediately operational staff.

The then Federal Minister of Defense Volker Rühe said:

"The ability to save one's own citizens abroad from danger to life and limb in an emergency is a fundamental responsibility of every state."

At the end of 1994, the events led to a realignment of security policy. German reaction forces should be designed and equipped to joint forces across and in cooperation with the alliance partners are able to carry out rescue and relief operations in a hostile environment. In the summer of 1994, the army command staff worked out the conceptual basis for German special forces and a year later, on September 28, 1995, the Army inspector, Lieutenant General Hartmut Bagger, issued the “Target and Planning Concepts Special Forces” .

Another cornerstone that summarized the change in foreign and security policy was the address given by the then Federal President Roman Herzog to the German Society for Foreign Policy on March 13, 1995, in which he stated that "the end of free-riding [...] achieved ”and now it must apply that Germany take over the political and military responsibility in the world that corresponds to its increased weight.

In the spring of the same year, the planning was so advanced that the Federal Minister of Defense officially presented the establishment of a “Special Forces Command (KSK)” to the Defense Committee of the German Bundestag in his departmental concept. In it, the original plans, only one force for the "rescue and evacuation of German citizens and / or other people in special situations abroad" were considerably expanded. The tasks of “obtaining key information in crisis and conflict areas”, “protecting people in special situations” and “combat missions in opposing areas” were added.

In June the federal government ( Kohl V cabinet ) decided to set up the KSK.

Lineup

Rühe provided 41 million DM from his budget and initiated the establishment of a corresponding special unit, the Special Forces Command. Major General Volker Löw , Commander of the Air Mobile Forces (KLK) and 4th Division, officially put the KSK into service on September 20, 1996 in the Graf Zeppelin barracks in Calw. The training company started immediately. The tradition of the Airborne Brigade 25 "Black Forest", which was decommissioned on April 1, 1996 , was continued in the Special Forces Command and the KSK was part of the Air Mobile Forces Command / 4. Division (KLK) subordinated.

The soldiers were primarily recruited from the former B1 paratrooper companies (command) of the individual airborne brigades, which had already been trained to rescue hostages and command operations and were now absorbed by the KSK in the course of this restructuring. In addition, many soldiers from Fernspähkompanien 100 and 300, which were also dissolved in 1996, came to the KSK and are still considered to be the most experienced members of this unit, the so-called veterans . Other soldiers came to the KSK from areas designated as “green uses” of the army, such as paratroopers , mountain fighters and hunters . Occasionally, specialists were also recruited from other parts of the Bundeswehr. The integration was rounded off with new equipment, which was also adapted to the largely new deployment profile of "Crisis preparedness and crisis management" and was supplemented by equipping the KSK with its own management, telecommunications and support staff.

Structure (as of September 20, 1996):

- Rod

- Headquarters and telecommunications company

- Support company

- Telecommunication command company

- Command companies 1 and 2

- Training and testing center

At this point in time, the first operational structures within the KSK were already in place, especially in the area of “Rescue and Liberation”.

Shortly after the installation, 25 KSK soldiers, who were to form the future basic training staff, were sent to GSG 9 in Sankt Augustin in order to familiarize themselves with the precision rifle system of the anti-terrorist unit of the Federal Border Guard (BGS) in several courses , as this is clearly different from the military sniper deployment differs. This training lasted until 1998, when the KSK had set up its own training base.

The KSK soldiers also learned how to free hostages from planes, buses and trains. They were then sent to the British Special Air Service in Hereford , where the Calwers deepened the battle of command, and then to Israel , where they were trained in counter-terrorism by the Sajeret Matkal . Finally, in the United States , the Special Forces at Fort Bragg deepened shooting at great distances with the Barrett M82 , which was not yet introduced into the German Armed Forces at the time .

Initial criticism

A rather casual statement made during the official press presentation of the KSK in Calw by the then Inspector of the Army Lieutenant General Helmut Willmann that the German Bundestag might no longer be involved in the decision in the event of an evacuation operation caused irritation in Parliament as a member of the parliamentary group Alliance 90 / The Greens addressed this.

As early as 1996 there were demonstrations of the peace movement in Calw and later also during the Easter marches regular criticism of the KSK and its orientation. The " Tübinger Informationsstelle Militarisierung eV " (IMI), which was founded as a reaction to the establishment of the KSK on the same day, classified the KSK as "undemocratic" and saw it as an instrument for "worldwide German power politics" was in charge of these campaigns .

Tobias Pflüger , the founder of IMI, fundamentally questioned the constitutionality of certain KSK deployment scenarios. He explains that the Federal Constitutional Court set two requirements for the Bundeswehr to be deployed outside of NATO territory:

"1. The Bundestag must approve this by a majority before an operation (parliamentary reservation). 2. A military action may only be carried out within the framework of a 'collective security system'. The special troops Command Special Forces should also be 'used' in purely German military operations. Military intervention should also be possible if there is no Bundestag resolution yet, as some operations would have to be planned in secret and some military actions would have to be carried out very quickly. These are two planned breaches of the constitution! "

From the ranks of the peace movement, the accusation was repeatedly raised that the KSK was "withdrawn from any democratic control and public criticism" due to its conception and the prevailing secrecy.

The defense policy spokeswoman for the Bundestag faction of Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen, Angelika Beer , stated in parliament that suitable police forces already existed for rescue operations like in Rwanda and that a corresponding military component was therefore not necessary. However, this assessment was contradicted by police and military experts, who considered the statement to be correct for an orderly rule of law as an operational area, but not for crisis and war areas in which state organizational forms have ceased to exist and warlords , mercenaries and militias are operating. Because a police operation is not possible there, as this requires a “safe environment” and the police are generally not trained for war operations. Even the GSG 9 is primarily trained to rescue hostages, but not to operate in a hostile environment.

Both in the media and in politics, criticism was expressed that the future tasks of the KSK were not adequately communicated in the official presentation. The federal government has regularly put the subtask of rescuing “German citizens abroad from the clutches of terrorists” in the foreground, but the actual scope of the KSK mandate, the “switching off command centers and important telecommunications facilities in the depths of the enemy Space as well as the acquisition of strategically and operationally important news ”, the“ defense against terrorist threat ”, the“ fight against subversive forces ”and“ covert operations ”were not fully publicly discussed.

The debate about the meaning and benefits of the KSK reached its first climax when, on December 18, 1996, the Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen parliamentary group put a small question with a total of 53 individual questions to the federal government Tasks of the KSK, its relationship to GSG 9 and the help of the NATO partners with the setup and training was discussed.

A dilemma for the Bundeswehr was already evident in this phase. On the one hand, for tactical reasons, efforts were made to maintain secrecy in order not to endanger the operational safety of the KSK. On the other hand, the leadership of the Bundeswehr tried to create a counterpoint to the criticism of the peace movement and Alliance 90 / The Greens. In addition, they wanted to increase awareness of the KSK in order to interest as many applicants as possible.

The debate about the meaning of the KSK flared up again when in mid-March 1997 paratroopers practiced flying out threatened citizens, but almost at the same time "the normal Bundeswehr" (quote from the Federal Minister of Defense Rühe ) carried out such a mission in Operation Libelle successfully performed.

Production of full operational readiness, "Schneller Adler 97" and press coverage

In April 1997, the KSK was ready and demonstrated in terms of positive press for the first time during the military exercise Fast Eagle 97 from 1 to 10 September 1997 on the military training area of Baumholder and the airbase Mendig its operational capability in public. A total of 1,600 soldiers with 20 helicopters, 11 transport aircraft and almost 500 vehicles took part in the maneuver , which was led by Volker Löw, the then commander of the Luftmobile Forces Command (KLK). The large-scale exercise simulated the liberation of hostages from terrorist control abroad (assumption 1,200 km away, Baumholder country of operations ) and the evacuation of German citizens. Federal Minister of Defense Volker Rühe was on site to personally inspect the maneuver in Mendig.

The public demonstration of the capabilities did not fail to have the intended effect, and the media reported the event and the troops largely positively. The question of financing such a special unit in the age of disarmament and in the area of tension between high-risk operations and insufficient financial compensation for the soldiers was only asked marginally. Likewise, the point of view of whether the Bundeswehr actually “only” affords this troop of over 1,000 men to rescue hostages abroad and, if so, why, was hardly discussed.

First restructuring, Balkan deployment and first public deployment confirmation

Increase

In 1998 the number of forces was doubled with the establishment of Command Companies 3 and 4, and the force began to carry out missions around the world. Almost all missions were carried out in secret.

Balkan use

The KSK had its first known operation on June 15, 1998 when it, together with French SFOR units, arrested the Bosnian Serb and war criminal Milorad Krnojelac in Foča ( Bosnia and Herzegovina ). On the same day, Krnojelac was transferred to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague using SFOR air capacities .

KSK soldiers also succeeded in arresting the Serbian paramilitary Radomir Kovac on the night of August 1st, 1999 in Foča . In the same month, German and Dutch (CLAS Korps Commandotroepen) special forces arrested three further war criminals in Orahovac, Kosovo .

Another access took place in October 2000 again in Foča. The aim was the arrest of Janko Janjic and his transfer to the war crimes tribunal in The Hague. During the access (operation "Kilo 2"), however, according to reports by "Spiegel" on September 24, 2001, an incident occurred in the course of which 43-year-old Janjic killed himself with a hand grenade. Three KSK soldiers were injured in the process.

In the autumn of 2000, KSK members carried out a so-called cold hit together with Dutch soldiers , an urgent mission without a thorough risk analysis. Several Serbs were captured and then transferred to the UN. A day later, however, it was reported that the prisoners were all able to flee.

Confirmation of employment

In 2000 it was officially confirmed for the first time in a television report by ARD that the KSK had already carried out several missions in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo at this point in time . The then acting inspector of the army , Helmut Willmann , disclosed this information himself, but without going into detail.

OEF and ISAF - Two independent mandates and separate command structures

On November 16, 2001, the German Bundestag decided to allow German forces to participate in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in the war on terrorism and, on December 22, 2001, to support the International Security Assistance Force ( ISAF ) by the German Armed Forces.

The ISAF mission is to 1386 including on the basis of the resolution of the UN Security grant of a secure and stable environment for civilian reconstruction support the Afghan government in creating. ISAF is militarily led by the NATO headquarters Allied Joint Force Command Brunssum . The area of deployment of the German armed forces under ISAF mandate was initially limited to Kabul and the surrounding area, only since September 21, 2005 has it basically included the regions “North” and “Kabul” defined by the NATO Council.

The aim of Operation Enduring Freedom, on the other hand, is to fight international terrorism. The US Central Command (CENTCOM) is in charge of all OEF forces . Under the mandate of the German Bundestag, German special forces (upper limit 100) were made available from 2001 to 2008, which could be deployed throughout Afghanistan. This mandate was canceled by the Bundestag on November 13, 2008.

Already two months before the first OEF mandate was granted, in September 2001, the former commander of the KFOR peacekeeping force in Pristina and Kosovo as well as the Bundeswehr contingent in Somalia , General Klaus Reinhardt , warned that the KSK was intended for them Task too small, he lacks the necessary equipment and the Bundeswehr does not have the necessary air transport capacities.

After an advance command had first inspected the Camp Rhino site south of Kandahar , forty commandos and sixty supporters of the KSK, led by a colonel of the US Army Special Forces from Oman , arrived in mid-December 2001 . According to the requirements of the ISAF mandate, units of the Bundeswehr were initially deployed in a multinational coalition led by the United States.

The elite unit Command Special Forces (KSK) was added to the Bundeswehr in Afghanistan. It arrested Taliban leaders and cracked down on the Islamists. Allegedly the KSK killed more enemies in Afghanistan than the rest of the Bundeswehr put together. So far, neither the KSK nor military experts have questioned this claim. How many Taliban killed the German armed forces is not known. In the case of the Bundeswehr, when asked, they only say, "As a matter of principle, one does not count dead enemies".

Well-known missions in the context of Operation Enduring Freedom

Participation in the K-Bar Task Force

Task Force K-Bar was the first multinational Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force - South to operate first from Oman , then from forward field bases in southeast Afghanistan under the command of Captain Robert Harward ( US Navy ) from October 2001 Operated against the Taliban and suspected Al Qaeda activists until April 2002 . A total of 42 reconnaissance and surveillance missions and an unknown number of combat missions led to the capture (107 men) and death (115 men) of numerous Taliban and Al-Qaida fighters. The KSK was involved and initially had the task of identifying Taliban networks, breaking identified personal connections through arrests and digging weapons caches. These were, however, not very explosive orders. This was due to an initial distrust of the Americans, British and French, who wanted the difficult missions to be carried out by established special forces.

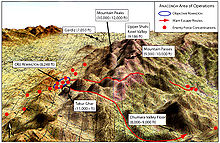

Battle for Tora Bora

Nevertheless, the KSK was immediately used in the context of the Battle of Tora Bora and the OEF mandate for reconnaissance and secured the military deployment of the Americans and British on the flanks of the mountain range. The KSK was also involved in three access operations that were successfully carried out against suspected camps and cave systems by Taliban and Al-Qaeda fighters. Various US media praised the good cooperation with the KSK and the professionalism of its soldiers at the beginning of January 2002, but Federal Minister of Defense Rudolf Scharping only confirmed the operations at the beginning of March.

Operation Anaconda

KSK soldiers were also actively involved in the controversial Operation Anaconda in March 2002. During this undertaking within the OEF framework, a civilian (goatherd) probably unmasked a secret observation post of the KSK by chance. This then led to the abandonment of these observation positions and retreat. The German approach was heavily criticized by the Americans, who allegedly used to solve such threats by shooting ("neutralizing") such civilians in order not to have to break off their mission.

Award for the Task Force K-Bar service

On December 7, 2004, the then US President George W. Bush awarded various special forces that were part of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-SOUTH / Task Force K-Bar operating in Afghanistan between October 2001 and March 2002 , including the KSK , the Navy Presidential Unit Citation for "extraordinary courage, ingenuity and aggressive fighting spirit in combat against a well-equipped, well-trained and insidious terrorist enemy".

As part of Operation Enduring Freedom and ISAF from December 2001 to October 2003, up to 100 KSK soldiers were continuously deployed in Afghanistan. The troops were mainly involved in reconnaissance operations in the Afghan- Pakistani border area and were later also assigned to the Kabul area. Their task was to obtain key information.

The Murat Kurnaz case

After his capture by US forces as a suspected Taliban fighter in 2002 and after more than four years in prison in Guantanamo , Murat Kurnaz accused two KSK soldiers of ill-treating him in Kandahar , Afghanistan . After an initial denial, the federal government admitted contact with KSK troops, but denied mistreatment. In October 2006, the Bundestag decided that a committee of inquiry should investigate the allegations and investigate the operations of the KSK in Afghanistan in general. He set up the Defense Committee, which did not meet in public. After about a year, the Tübingen public prosecutor closed the investigation against the two accused KSK soldiers for lack of evidence. It is still testimony against testimony. The allegation was derived from the testimony that the soldiers had colluded. The Defense Committee's final report, which appeared after 22 months, could neither refute nor confirm the allegations of ill-treatment, but did not deny Kurnaz its credibility. He stated that the federal government had now better fulfilled its duty to inform the Bundestag about the operations of the KSK. A regulation for this is still pending.

In addition, further problems of the KSK mission in Afghanistan were mentioned. These ranged from the general questionability of the military value of the mission to the soldiers' excessive consumption of alcohol and legal problems in connection with arrests and cooperation with foreign armed forces.

Internal criticism and public relations work by the Bundeswehr

After the conclusion of Operation Anaconda, by March 2002 at the latest, according to a KSK officer in the Kurnaz investigation committee, there would actually have been “no more meaningful assignments”. The then commander Reinhard Günzel commented on this as follows:

“The men sat for ten days at an altitude of 4,000 or 3,500 meters on a mountain peak in the snow and observed and reported the surrounding area. That's one thing for which you don't need special forces. "

As of June 2002, thirty-seven US soldiers had been killed in the course of Operation Enduring Freedom. The increasing number of casualties caused the United States to intensify its air strikes. For example, Boeing B-52 bombers flew heavy attacks on the Scha-i-Kot Valley between the towns of Shkin and Khost, which led to an increase in the number of victims among the Afghan civilian population. High-ranking German officers criticized this approach in part also publicly. The Federal Ministry of Defense responded with changing press work. More and more journalists were invited to press meetings either in Calw or in the Hindu Kush.

In autumn 2002 there was reports of "frustration" among the KSK soldiers, who felt they were underutilized and that KSK commanders had asked their chief employer to consider withdrawing the troops from Afghanistan. At the same time, the US Central Command (CENTCOM) began withdrawing American and British soldiers from Afghanistan in preparation for the planned Iraq war. This made the KSK missions less effective because of the lower means of transport and air support, but the federal government ( Schröder cabinet ) nevertheless decided against a withdrawal so as not to further deepen the diplomatic turmoil between Germany and the USA due to the lack of support for the Iraq war . The FAZ headline on November 3, 2002: "Germans on the front line". The new Federal Minister of Defense Peter Struck , who had meanwhile replaced Scharping, informed the FAZ that the KSK soldiers “had earned the recognition and respect of our allies with their commitment and high level of professionalism”. “With this commitment” Germany shows “its willingness to take on extensive military responsibility”.

Even after the end of the Iraq war, the KSK remained in Afghanistan, contrary to the official KSK mission statement “In, do the job, out again”, as the Army Inspector Gert Gudera described it as the “ideal case”. In an interview with Die Welt am Sonntag on August 24, 2003, Struck drew a first interim assessment of the KSK's deployment in the Hindu Kush. He emphasized that the Bundeswehr had to be strengthened in the areas of NBC defense forces, communication and special forces.

The KSK should therefore be expanded consistently, but with care. Because "we don't need rambos for this, but responsible soldiers for difficult tasks, such as the liberation of German citizens". In the same interview, the then Federal Minister of Defense also indicated that the KSK had played a not inconsiderable role in the liberation of the “Sahara hostages” who had been held in Mali since Easter 2003 (see Sahara hostage-taking 2003 ).

Second restructuring in 2005

In 2005, the structure of the KSK was changed for the second time in its young history, when an independent medical center was set up as a result of restructuring measures from the medical area , which belonged to the staff and supply company. In addition, the emergency services were supplemented by the so-called special command company, which corresponded to a reinforcement of 20 percent.

Well-known assignments within the framework of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)

According to Sören Sünkler, KSK soldiers were relocated to Afghanistan again in May 2005. They performed different tasks there and helped to create a “safe environment” in different places. According to this source, the KSK was used both as part of the ISAF mandate in the north and in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in the highly competitive south. The Bundeswehr mainly reported on the peace-stabilizing aspect of the ISAF mission; it did not comment on the KSK's contribution to both operations.

In July 2005 there was a scandal when the magazine Stern published an article about such missions and grievances within the KSK. The author Sören Sünkler interprets the statements of KSK soldiers quoted there as follows:

“In its July 2005 edition, the Stern published the criticism of some KSK insiders who wanted to use it to expose grievances. The political mendacity under which the commandos in Afghanistan are burned, the inadequate military preparation of the operations and the inadequacy of the leadership to plan and conduct special operations were particularly denounced. "

In addition, the Stern published a number of images that showed KSK soldiers in action and described the Paktika province in the southeast on the border with Pakistan as a possible location for the troops. The Federal Ministry of Defense (BMVg) declined, as usual, to comment on the allegations made there, stating that no information was given on operations and internal processes in special forces of the Bundeswehr. In mid-July 2005, the defense policy spokesman for the SPD parliamentary group, Rainer Arnold , replied to the newspaper Die Welt when asked whether the KSK also took action against drug lords: “There are overlaps. A terrorist can finance his terrorist business with drugs. "

Since August 2006, soldiers of the KSK have been deployed again in northern Afghanistan to track down and fight terror suspects and irregulars in order to protect the German contingent from the threat of local warlords .

On September 12, 2006, General Inspector Wolfgang Schneiderhan Army - Staff Sergeant Jonathan Zapien from the 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne) personally awarded the Bundeswehr Medal of Honor . Zapien had saved the life of a KSK soldier during the deployment period in eastern Afghanistan from June to October 2005.

In October 2006 the KSK arrested a group of bombers in Kabul . Allegedly they are the masterminds behind the attack on a Bundeswehr bus that was attacked in 2003. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung saw this as an “important political signal” to the effect that German forces were also successfully deployed in Afghanistan. In May 2013, Federal Minister of Defense Thomas de Maiziere confirmed the death of a KSK soldier in Afghanistan.

Lack of coordination with the conventional military in the operational area

According to an internal report by the Federal Minister of Defense ( "Van Heyst" report ), the Bundeswehr missions abroad are dramatically poorly organized. The German ISAF operations in Afghanistan suffered from the base to the leadership under improper management, reported the weekly newspaper Die Zeit in advance, citing this report. In addition, KSK forces largely bypass the Bundeswehr Operations Command (EinsFüKdoBw) in Potsdam, as they are largely not under the NATO High Command of ISAF ( Allied Joint Force Command Brunssum ), but rather under the US Central Command as part of Operation Enduring Freedom (CENTCOM) are subordinated. This endangers the security of the German soldiers stationed in Afghanistan.

Unsuccessful access to Kunduz

At the end of April 2008, a joint operation by forces of the German Armed Forces and the Afghan armed forces was carried out near the Afghan city of Kunduz . 13 people were arrested, two of whom were suspected of having been involved in attacks against the Bundeswehr. The actual target, the mastermind behind the attack on German soldiers in Kunduz in May 2007, who was monitored by KSK soldiers, escaped.

Weapons found in Jowzjan

In July 2008, members of the KSK, working with Afghan security forces, discovered a large arsenal in Jowzjan province , 120 kilometers west of Mazar-e Sharif . 1,100 mortar shells, propellants and detonators were hidden in it.

Establishment of Task Force 47

When the Afghanistan mandate was extended on November 13, 2008, the Bundestag had expressly agreed that KSK would no longer be deployed. In 2009, however, internal documents of the Bundeswehr became known, according to which the KSK had provided soldiers for a Task Force 47 (TF 47) in Kunduz, who had played an important role in the air attack near Kunduz on September 4, 2009 , for example .

Arrest of Abdul Razeq

On May 7, 2009, the KSK succeeded in arresting the Taliban leader Abdul Razeq , who had been wanted since 2008, near Faisabad in northern Afghanistan. After an unsuccessful access to Razeq's house, Razeq fled into impassable terrain, where the German forces managed to track him down after several hours of pursuit. The arrest itself was then carried out by Afghan security forces. Abdul Razeq is accused of planning and carrying out at least three attacks on ISAF and NATO troops in Afghanistan in 2008. A KSK member was slightly wounded during the operation.

Operations in 2010

Also in the Afghanistan mandate of the Bundestag of February 26, 2010, the deployment of the KSK in Afghanistan was not decided. In the press, however, questions were cited by MPs as to whether the TF 47 in Afghanistan had taken on tasks of the KSK and thus the OEF, contrary to mandate. In fact, the commander of the KSK, Brigadier General Hans-Christoph Ammon , declared on a Bundeswehr website in May 2010 that the KSK was also deployed in Afghanistan, “we make no secret of it”.

With regard to targeted killing operations, Brigadier General Josef Dieter Blotz told Tagesspiegel that one of the tasks of the Special Forces Command (KSK) was to hunt down the Taliban and “eliminate” it: “The Defense Ministry has definitely ruled out targeted killings by special forces of the Bundeswehr. However, the Bundeswehr's Special Forces Command (KSK) was also used to eliminate networks of extremists. "

In September 2010, a KSK commando arrested the high-ranking Taliban leader Maulawi Roshan . He was arrested in a night operation in a homestead in Chahar Darreh near Kunduz .

Mullah Abdul Rahman arrested

On the evening of October 19, 2012, the KSK and Afghan Special Forces succeeded in arresting Mullah Abdul Rahman, the “shadow governor” of northern Afghanistan, near the village of Ghunday Kalay and handing it over to the Afghan authorities.

losses

The command's losses are usually kept secret. On May 5, 2013, Federal Minister of Defense Thomas de Maizière informed the public for the first time that a KSK soldier had fallen in action. This happened during a mission in northern Afghanistan, and the casualty was the first KSK soldier to be killed in action in Afghanistan. Until then, according to various reports , soldiers had only died in traffic accidents and accidents during training, for example during diving exercises, parachute jumps or practice shooting.

Further deployments or training missions

Deployment in Libya 2011

According to information provided by the Frankfurter Rundschau KSK soldiers were also involved in the evacuation operation "Pegasus" involved in during the riots in Libya 132 people with the help of two on 26 February 2011, a total Transall transport aircraft from the eastern Libyan desert town Nafurah to Crete were brought. According to the Frankfurter Rundschau, the Federal Ministry of Defense did not want to comment on any involvement of the KSK.

Training mission in Afghanistan (since 2018)

As part of the NATO mission Resolute Support , the KSK has been in Afghanistan as a training contingent in cooperation with the Maritime Special Forces of the Netherlands (MARSOF) since 2018.

Training mission in Jordan

Training of Jordanian special forces as part of the Military Assistance mission "Arabian Leopard" in 2019.

Evacuation mission in Afghanistan in August 2021

KSK soldiers were summoned to Kabul airport in August 2021 during the Taliban's takeover to assist in the evacuation of those authorized to leave the country . During one operation, KSK soldiers, in cooperation with the US military, evacuated people by air from the city of Kabul to Kabul Airport. Reports on whether KSK soldiers actually operated outside of Kabul airport were contradicting another mission in the context of the same mission.

Mission-related problems

Criticism for lack of aircraft for special missions

The KSK needs helicopter support for the transport to the place of deployment or to an operational area. In order to be able to operate independently and flexibly with the greatest possible self-protection, these must meet special requirements. These include, for example, large ranges (through additional tanks or air refueling capability ), connectivity (through radio data transmission), all-weather / night-time suitability (through appropriate avionics ) and high self-protection (through EloKa equipment and a chaff / flare dispenser (decoy system)).

In 2008 the Bundeswehr did not have such aircraft. Among other things, Germany came under fire from the US military leadership, as it relies on appropriate support from the USA or Great Britain for its special forces operating in Afghanistan.

Only in the medium to long term will the KSK with the upgraded CH-53 , the multi-purpose helicopter for special forces Airbus H145M , which will be available from 2017, and the air force helicopter for armed search and rescue (CSAR: Combat Search and Rescue ) that will be available within the Bundeswehr fall back and become more independent of NATO partners.

Since the training and development of procedures for airborne special operations means a lot of effort for both the soldiers of the KSK and the aircrews, this was started in 1995 with the establishment of the "CSAR core group" well before the introduction of corresponding aircraft. Since a small part of the required capabilities can also be covered with currently available helicopters, an "SOF (Special Operations Forces) Air" element (Flying Department 251) was set up in Laupheim for the then Middle Transport Helicopter Regiment 25 "Oberschwaben" of the Army Aviation is tailored to the range of operations of special forces. The CH-53 of the helicopter squadron 64 is currently used for this . The further use of the liaison helicopter BO-105P1M with the "Swooper" kit, with which commandos soldiers can be moved to the two outer sides of the helicopter and can be used directly from the flying aircraft, was discarded because the BO-105 is being decommissioned. At the same time, another approach to support is being pursued in the Air Force by the CSAR core group.

Capture-or-kill missions are prohibited

In connection with the failed access operation in Kunduz in 2008, the international discussion on the question of whether terror suspects should be specifically killed was rekindled.

The German position on this is clear. It expressly permits the use of lethal force only in the event of an actual or imminent attack. For reasons of principle of proportionality, the Federal Government rejects the “targeted killing of suspects” in the sense of “liquidation” ”and refers to the rules of engagement (RoE: Rules of Engagement ) established with NATO . Further restrictions (so-called caveats ) with an impact on the ISAF operation plan do not exist on the part of Germany.

The incident raised the question of the compatibility of the KSK with other special forces of the Allies, which would have “fewer problems with it”. For example, British and American forces identified, tracked down and often “switched off” the “target persons” [...] using laser-guided weapon systems ”. Der Spiegel further explains:

“The Federal Government regards the Allies' approach as' not in accordance with international law '. So it is hardly surprising that NATO's Afghanistan mission crunches and cracks.

The critics accuse the Germans of achieving the opposite of what they are supposedly striving to achieve: 'The Krauts let the most dangerous people go and thus increase the threat to the Afghans and all foreign forces here,' said a British officer in the Kabul ISAF- Headquarters on Great Massoud Road uncomprehending. "

Failure of the KSK to intervene in the case of hostage liberation by the foreign military

On September 29, 2008, a tour group abducted in Egypt was released after being detained for ten days. According to the Egyptian Defense Minister and Commander of the Egyptian Armed Forces, Hussein Tantawi , the liberation was carried out by Sudanese and Egyptian soldiers. According to the former hostages, however, no rescue operation should have taken place; instead, the kidnappers released the prisoners and even provided them with a vehicle to escape to the Egyptian border. One of the former hostages, Ibrahim Abdel Rahim, reported that he had repeatedly managed to secretly pass on the GPS data of their location, but the military 300 km away did not intervene. According to the Federal Ministries of the Interior and Defense, German special forces (KSK and GSG 9 of the Federal Police ) were also indirectly involved in the liberation by being involved as support forces on site. In fact, the KSK was not involved in combat operations there.

Refusal to authorize a military release of hostages - the hostage escapes

From mid-April to May 2015, a German development worker from GIZ was held hostage in the Afghan province of Kunduz . A military intervention, which the KSK had prepared by sending 178 soldiers, did not take place. The hostage managed to escape without any help.

Refusal to approve a military hostage rescue - release by handing over a ransom

A German development worker from GIZ was held hostage in Kabul from mid-August to October 2015 . The Foreign Office asked the KSK for help, which then sent its own soldiers to Afghanistan to rescue hostages. Instead of a military hostage liberation , which was ultimately not approved, only the handover of the ransom was secured by KSK soldiers.

Corruption suspected

During several training missions of the KSK in Namibia between 2014 and 2019, the company of a former KSK soldier there was commissioned with the implementation of official training missions on "land relocation under extreme conditions". The BMVg is said to have rejected his new application after receiving information about his possible right-wing extremist attitude. According to media reports, the BMVg is examining the case and the related awarding practice.

Grievances within the KSK

Any ideological proximity of a commander to Nazi folklore

Reinhard Günzel , commander of the KSK end of 2003, in his book Secret Warriors , which he in 2005 together with the GSG-9 founder Ulrich Wegener and the former Wehrmacht officer Wilhelm Walther in which the publishing complex of the extreme right-wing publisher Dietmar Munier belonging Pour le Merite Verlag published, the KSK in the tradition of the Wehrmacht special unit Division Brandenburg .

Then put the Left faction in the Bundestag a written question whether the KSK see the Brandenburg Division as tradition stiftend. In doing so, she expressed that, in her opinion, the commander's relationship to the crimes of the Wehrmacht in World War II was not sufficiently clarified because the Brandenburg Division was accused of violating the Hague Land Warfare Regulations . The federal government replied to the left-wing parliamentary group that the traditional relationship of the KSK was based on “special qualifications and pride in having successfully completed a tough and demanding training” and that assumptions about “right-wing extremist views were based on Brigadier General a. D. Günzels during his active service as commander of the KSK “have no basis whatsoever. In doing so, the government made it clear that there had never been an official traditional reference to the Brandenburg Division and that Günzel's journalistic statement was his private opinion.

Reinhard Günzel was dismissed on November 4, 2003 by Federal Minister of Defense Peter Struck because of a letter of support to the former member of the Bundestag Martin Hohmann , which he wrote on official paper and thus in his position as commander of the KSK. (Hohmann was expelled from the CDU / CSU parliamentary group because, in a speech about collective guilt with reference to the crimes of the October Revolution , he had said "Therefore, Jews could be called 'perpetrators'' with some justification.")

Right-wing extremist soldier Daniel K.

In early April 2008, the magazine published Der Spiegel in its issue 13/2008 that the KSK Captain Daniel K. member of the Bundeswehr critical Soldiers Association Darmstadt signal , Lt. Col. Jürgen Rose had threatened, via a solicitation to him e-mail: "You will be observed , no, not from impotent, instrumentalized services, but from officers of a new generation who will act when the time makes it necessary. ”In addition, Rose was described as an“ enemy within ”who had to be“ smashed ”. His disciplinary officer responded with a disciplinary action, but left it with a simple reprimand. The initiation of judicial disciplinary proceedings did not take place. This simple disciplinary measure does not prevent the promotion of an otherwise proven soldier, according to the federal government at the press conference on May 2, 2008. In mid-June 2008, Der Spiegel reported in the 25/2008 issue that the Bundeswehr had imposed a disciplinary fine of 3000 euros on Jürgen Rose was imposed because he called the Special Forces Command a “sewer” and accused the unit of right-wing tendencies . Lieutenant Colonel Jürgen Rose was retired early and, as a civilian, continues to work in the vicinity of the Darmstadt Signal and the peace movement.

Daniel K., now in the rank of lieutenant colonel , was banned from wearing uniforms and duties in February 2019 due to right-wing extremist posts in a Facebook group. In his remarks he shared the ideas of the Reich citizens , among other things he called for the abolition of the office of Federal President . In the same year he was discharged from the German Armed Forces due to his connections to the Identitarian Movement , which was uncovered by the Military Counter-Intelligence Service , and was subsequently on sick leave with depression and a post-traumatic stress disorder. He was also accused of fraudulent misrepresentation because, during a job interview in 1991, he was said to have concealed the fact that he had worked for the Young Nationalists for two years in the late 1980s . The dismissal was lifted by the Administrative Court of Baden-Württemberg in December 2020 at the latest. The reason given was that K. had withheld his political history, but disclosed it before he was appointed as a professional soldier.

In a letter to his comrades, K. described himself as a “deeply national-conservative patriot ” who was “definitely not a so-called Nazi ”. He was the victim of a campaign because he was "in the way of certain media-political, but also cowardly opportunistic forces in uniform".

Right-wing soldier Andre S.

As a KSK soldier, Andre S. was the leader and namesake of the Hannibal network . In the course of terror investigations against Bundeswehr soldiers from 2017 onwards, he was a contact for the Military Counter-Intelligence Service (MAD) at the KSK. He was interrogated as a result of criminal proceedings against his liaison at the MAD. In doing so, his role as network administrator and co-founder of the Uniter association emerged. In 2017, the BKA investigators found two handfuls of cartridges, smoke and signal grenades and a box with detonators for hand grenades in his home and parents' house. In September 2019 , the Böblingen District Court imposed a fine of 120 daily rates on him for violating the Weapons Act and the Explosives Act . He appealed against this. He was transferred from the KSK, but not released from the Bundeswehr. After leaving the KSK, Andre S. was the “information person” for right-wing extremist tendencies in the Bundeswehr for the MAD. In September 2019, André S. stated that his military service as a temporary soldier would expire at the end of the month. He thus escaped disciplinary proceedings . The Frankfurt Higher Regional Court had not found sufficient suspicion of terrorism against him, but the Federal Prosecutor continued to accuse him of planning right-wing extremist attacks and examined a lawsuit for them.

Observation by the military secret service as a result of widespread right-wing extremism

The Military Counter-Intelligence Service (MAD) reported at the beginning of 2020 that around 550 suspected right-wing extremism cases were being investigated throughout the Bundeswehr . According to the President of the MAD, the KSK is particularly affected, because here the number of suspected cases is around five times as high as the average. The reason for this is the elitist self-confidence of the isolated unit, whose intensive network of relationships also led to risks. In a confidential briefing, the President of the MAD admitted to members of the Bundestag that at least nine of around 20 so-called suspected cases had been confirmed and corresponding sanctions had been ordered against the soldiers. Sanctions were imposed on nine soldiers from the command because of their convictions, and three KSK soldiers were banned from wearing their uniforms. In March 2020, one soldier classified as a right-wing extremist was released, and another was about to be released. Two soldiers were transferred. Disciplinary proceedings are ongoing in two other suspected cases. Only in one of the total of 20 suspected cases did the suspicion turn out to be unfounded by March 2020.

In mid-September 2021, it was announced that the MAD was investigating two more cases. In one case, the charge is made that in 2015 a sergeant major raised a black-white-red flag himself or at least tolerated it. The second allegation concerns a lieutenant who in 2014 shared “a small” number of pictures in a WhatsApp group that were in a right-wing extremist context.

Islamist soldier Ömer S.

On June 17, 2020 it was reported that the Islamist staff sergeant Ömer S. was reported to the Military Counter-Intelligence Service (MAD) in 2019 and, after being classified by the MAD as an extremist, was dismissed from the Bundeswehr at the beginning of 2020.

Right National Staff Sergeant Philipp Sch.

In the summer of 2018, the commander of the KSK said of him that he was a "model commando soldier" and an "essential service provider" with pronounced social skills. Philipp Sch. was trained as a lifeguard, mountain guide and parachutist, among other things.

The Military Counter-Intelligence Service (MAD) observed, among others, Philipp Sch. since incidents in 2017. On April 27, 2017, a farewell party for Lieutenant Colonel Pascal D., company commander of the 2nd KSK Company, took place at the Bundeswehr location shooting range Im Bernet near Stuttgart . He wore among other things. a tattoo with a Chetnik flag. He completed a course and threw pig heads. The winning prize was supposed to be a prostitute booked for this purpose. She turned her observations to the public. To right-wing rock music, such as B. the Sturmwehr group , parts of those present showed each other the Hitler salute , including Philipp Sch. Pascal D. was then sentenced to a fine . Few others have been disciplined.

At the beginning of 2020, the MAD received information from Philipp Sch.'s son that his father had set up a weapons and ammunition hiding place. The MAD switched on the investigative authorities in Saxony on February 11, 2020. On March 23, 2020, the investigators received a search warrant, which resulted in a raid on the property of KSK soldier Philipp Sch. was carried out in Collm in northern Saxony . During the search, an extensive hiding place for weapons and ammunition was excavated in the garden. Several firearms (including an AK-47 ), several thousand pieces of rifle and pistol ammunition and highly explosive explosives (including two kilograms of PETN ), most of which came from the armed forces' stocks , were seized. In addition, right-wing extremist writings (including an SS songbook) were seized. An arrest warrant was issued against the 45-year-old sergeant , disciplinary proceedings were initiated , and investigations into violations of the War Weapons Control Act , the Weapons Act and the Explosives Act were initiated. At the beginning of December 2020, Philipp Sch. Released from custody against conditions, including a security deposit of € 15,000.

A lieutenant colonel from the anti-extremism department of the MAD who was involved in the investigation was suspended because he had investigative information against Philipp Sch. passed it on to a friend of the KSK soldier.

Many politicians expressed concern about the incident. The commander of the KSK, Markus Kreitmayr, sent a fire letter to the association in which he described the case as a “shocking climax” that “reached a new dimension for all of us”. He appealed to the soldiers to take action against right-wing extremists within their own ranks. He also called on these soldiers to leave the KSK and the Bundeswehr, otherwise they would be found and removed. The Federal Ministry of Defense put together a working group that was supposed to work out a package of measures by the parliamentary summer break that would “prevent right-wing extremist tendencies from the outset”.

On March 12, 2021, the Leipzig Regional Court sentenced him to two years' probation. The judge attested that he had a right-wing national mindset. Philipp Sch. was responsible in the 2nd company of the KSK for the planning and execution of target exercises and the ammunition handover to the soldiers. He explained his ammunition hoarding by saying that it was for official use to bridge existing bottlenecks in shooting training. In the trial, the defense stated that it was Philipp Sch. It seemed too risky to hand over stolen ammunition to the barracks as part of the amnesty . The lawyer said, among other things: "If he had done it, he would still be a highly respected commando soldier today." Would have connected threats of punishment? He would have achieved nothing because hardly anyone would have given anything. " Both the General Public Prosecutor in Dresden and the defense of Philipp Sch. did not appeal an appeal, whereby the judgment became final on March 19, 2021.

Fire letter from a whistleblower

In June 2020, a KSK captain sent a fire letter to Federal Minister of Defense Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer , in which he described right-wing extremist grievances within the association as profound and structural. Right-wing extremist tendencies are "recognized internally, but [...] are collectively ignored or even tolerated" and any reports are prevented during training, in some cases knowingly covered up, and members are told not to report any incidents. The prospective KSK soldiers are trained in a rigorous obedience, which internally by trainees “was compared with that of the Waffen SS ”. You would a bondage instilled that "with the boundaries of order and obedience is by the standards of the Bundeswehr as incompatible to evaluate." Disciplinary punishments are used "to make soldiers and, above all, critical officers compliant". As a result, there would be “a kind of cadaver obedience ”, a “culture of accepting illegal behavior” and a “toxic association culture”. The whistleblower attests to an instructor who uses the callsign “Y-88” ( 88 stands for Heil Hitler ) an “aggressive national-conservative attitude”. It is "naive" to believe that soldiers like Daniel K. are isolated cases. To remedy the grievances, the author suggested an external investigation and subsequent reform of the KSK.

In addition to the grievances in the Special Forces Command, his threatened transfer to another unit was also a reason for the whistleblower for his letter. The reason for the transfer was an “extramarital affair” which, according to the instructors, would show “unsuitable character”. The whistleblower saw this as an "arbitrary punitive measure" against him. According to the whistleblower, the transfer was stopped by KSK commander Kreitmayr after his letter became known . The whistleblower should then advise the leadership of the KSK on the reform.

Amnesty through the return of stolen ammunition

In February 2021, it became known that at the verbal order of the KSK commander, the KSK soldiers were able to return misappropriated ammunition from March to May 2020 and had no negative consequences to fear. This resulted in a larger amount of ammunition than was missing. Shortly thereafter, Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer admitted that she had known about the amnesty for months and had kept it secret from the Defense Committee.

Announced reforms in the wake of the revealed grievances

In response to the right-wing extremist incidents, Federal Minister of Defense Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer announced a reform package comprising 60 individual measures at the end of June 2020, the implementation of which should be completed in October 2020, and announced the use of an "iron broom". The measures include the dissolution of the 2nd command company of the KSK, which took place on August 1, 2020, the outsourcing of training, which the KSK had previously organized independently, to the infantry school and thus subordinate it to the training command ; In addition, a future maximum length of stay for KSK soldiers, which is accompanied by a transfer to other units of the Bundeswehr before they can be transferred from there to the KSK again. Furthermore, a stricter control of weapons and ammunition stocks for the KSK was announced, since - according to a report to the Bundestag - the whereabouts of 85,000 rounds of ammunition and 62 kilograms of explosives is unclear.

On June 29, 2020, MAD President Gramm spoke to the Parliamentary Control Committee for the first time about references to “right-wing extremist networks”. However, according to the general inspector's final report of June 9, 2021, this suspicion has not been confirmed.

assignment

Job definition

The Bundeswehr divides the KSK's mission into four main mission profiles and formulates it as follows:

- Protection of German institutions and forces abroad as well as of people in special situations

- Rescuing, freeing and evacuating people

- Military reconnaissance to create one's own information superiority

- Fight against high priority targets in enemy or enemy-occupied territory

The KSK is particularly capable of rapid and targeted commando operations while avoiding any escalation and so-called collateral damage as much as possible. Special forces are either used as a supplement to conventional military personnel or instead of them if the use of conventional forces is not indicated. The KSK is used in peacetime on the instructions of the Federal Minister of Defense when special tasks of great importance for strategic and operational management are to be fulfilled, which conventional military forces either cannot carry out at all or cannot carry out with the necessary effect. According to the German Armed Forces, the planning and execution of KSK operations must be carried out with a high level of secrecy, as otherwise the soldiers and the mission's objectives would be unnecessarily endangered.

Mission profile

enlightenment

(Remote) reconnaissance and monitoring of relevant military targets is used to obtain key information about troop movements, positions and human and material resources of the enemy. This can be done by special forces both in uniform and with covert operations . This range of operations also includes exploration and sounding out of possible areas of operation as part of advance commands as a decision-making aid for the further deployment of troop contingents. The preventive defense against enemy command units ( infiltration attempts ) and covertly operating forces also belong to this area. Soldiers of the KSK can also as a forward observer and as a forward air control are used to fire the artillery to direct or close air support to conduct.

Counterterrorism

The range of operations of the KSK also includes the defense against terrorist threats of all kinds. It not only contributes actively but also passively by protecting its own forces and facilities in crisis areas to ensure the freedom of operation of conventional troops. Other areas of responsibility include the liberation of hostages from all conceivable scenarios and personal protection of commanders and civil dignitaries abroad at risk. A military hostage rescue by the KSK never took place (as of June 2020).

Rescue, evacuation and recovery

Another type of operation is the evacuation, rescue and recovery from terrorist and war-related threats to personnel and equipment behind enemy lines (also using military force). The KSK is trained for search and rescue missions in combat situations (CSAR).

Commando operations

The classic use of the KSK takes place in command operations. These include the targeted capture, rendering useless or destruction of key enemy positions such as airfields, communication and command centers, artillery and missile positions, bridges, ports, supply bases, bunkers or other particularly valuable infrastructure of the enemy. These raids ( direct action ) are carried out in a coup, either at the front or, after successful infiltration, in the enemy rear.

Military advice

The KSK is involved in military cooperation and training support for potential NATO host countries.

Legal basis and legal issues

Like the rest of the German military, the KSK cannot take part in armed operations abroad without the consent of the German Bundestag . The only exception is imminent danger for German citizens . In this case, Parliament should be consulted as soon as possible.

Results of the committee of inquiry into the Kurnaz affair

The investigation into the Kurnaz case has shown that the legal basis for the capture of enemy combatants and terror suspects in Afghanistan is shaped by the national law of the allies. There is no common legal basis for action. In the opinion of the defense policy spokesman for Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen , Winfried Nachtwei , this “problem of legal interoperability” has led to the “deployment spectrum being shifted to the less intensive levels”.

The committee of inquiry into the Kurnaz affair highlighted many situations in which the soldiers act in a legally unclear framework. According to the FAZ, the possibility of torture by KSK soldiers after the Kurnaz affair could no longer be ruled out.

The Stern reported on the legal gray area in which KSK soldiers sometimes have to operate :

“ We saw in Afghanistan how disgusting US soldiers jumped at Afghans, kicks and butts were still harmless. You treated them like subhumans . The Germans had also seen the Americans flatten entire villages and tear out door locks during Operation Anaconda : Here boys, free to plunder . The high-ranking ex-KSK man says: The pictures of Abu Ghraib , the torture in Iraqi prisons, did not surprise me at all. Officially, the Ministry of Defense says that KSK soldiers only took a handful of prisoners in Afghanistan and let them go again. The truth is that we always had Americans with us when prisoners were taken. That's how they arrested the suspects, not us. Actually, German soldiers are not allowed to hand over prisoners to a country where the death penalty is imposed. Basically, it's a mess to send our boys in there with an unresolved legal situation , says the ex-officer. Will our 28-year-old trooper have one leg in jail if the Americans execute his prisoner? "

Lack of transparency due to the confidentiality practice

The KSK is perceived in society as a proven "elite force" that carries out secret operations in secret and possibly does so without sufficient parliamentary control. In contrast, the Bundeswehr tries to relativize this elitist character, because this can only be reconciled with the model of the citizen in uniform with a few difficulties . The Bundeswehr also regularly emphasizes that there are no special legal operational bases for the KSK and that, for this reason, it is on an equal footing with all other Bundeswehr units.

The political understanding of society has not yet developed sufficiently and the role of the special forces as an instrument of German foreign and security policy has so far been insufficiently discussed in public, also because of the lack of a strategic-operational target system for foreign missions of the Bundeswehr.

However, the federal government nourishes the public's distrust because it refuses to comment on the course of action and on successes or losses even after the missions have been completed. This non-transparent information policy is understandable with regard to a corresponding weighing of interests between the operational safety of the KSK on the one hand and the right to information of the public on the other hand, but it feeds doubts about the legitimacy of the KSK operations. Such a practice of secrecy also does not correspond to the political culture of the Federal Republic, since state action is usually public there.

The information and scandals repeatedly published by the press in its function as the “fourth power” do not contribute to promoting the public's trust in lawful action by the troops. At the same time, the federal government's restrictive public relations work underpins this perception.

The peace movement also criticizes the government's failure to inform parliament about the operations, either before or after. According to Section 6 of the Parliamentary Participation Act (ParlBetG) of 2005, the executive branch has a duty to inform the parliament, but as with previous deployments of special forces, it ignores these requirements, as it assesses the operational safety of soldiers as higher than that in the context of a public-law weighing of interests Parliament's right to participate. Even the representatives of the parliamentary groups would not receive all the information they wanted. For this reason, a number of parliamentarians are of the opinion that they are not adequately informed and criticize that they are not able to properly exercise the necessary parliamentary control.

In view of the contradiction between the Parliamentary Participation Act and the required secrecy, state practice has developed an informal procedure in which the Federal Ministry of Defense informs the representatives in the Defense Committee confidentially about such operations. Because this procedure continues to be criticized, the Federal Government has committed itself to informing the chairmen and deputies of the Defense and Foreign Affairs Committee every six months. Nevertheless, the question remains whether we can actually continue to speak of a “ parliamentary army ” when only 14 members of the Bundestag out of a total of 709 find out more about the KSK operations. This practice also does not change the informal character of this procedure and is therefore not suitable for allaying doubts about the constitutionality of this practice with regard to the parliamentary approval for the use of armed forces.

The German government responded to the question of ensuring parliamentary control of operations requiring confidentiality in 2007 with a letter to the parliamentary group chairmen with the suggestion that the informal procedure that is currently practiced should be slightly further developed, but retained. A bill by the FDP parliamentary group instead provides for the establishment of a parliamentary control body for special foreign missions, similar to that of the secret service committee . No decision has yet been made. Nevertheless, according to Georg Axer, legal assistant to Professor Seifert (University of Erfurt), the establishment of a Bundestag committee for special missions in the sense of the consistent requirement of parliamentary participation in operations requiring confidentiality would be a suitable measure to adequately resolve this tension between parliamentary control and confidentiality . However, only if the original draft of the FDP were modified in such a way that the legislature also included the “flexible operational army ” formulated in the 2006 White Book of the Bundeswehr in the design of the regulations on parliamentary participation.

The legitimacy of this practice is thus called into question by parts of the public, as they are of the opinion that the KSK is in fact more of a force of the executive than a part of a "parliamentary army".

In September, the Defense Committee found that the federal government had not yet adequately fulfilled its legal obligation to inform parliament about KSK deployments and that there was a need for regulation for an information procedure that would meet the requirements of the Parliamentary Participation Act (ParlBetG), but without to endanger the required operational safety of the soldiers.

The Bundeswehr Operations Command (EinsFüKdoBw) is responsible for conveying information about operations by the command . Journalists are mostly dependent on inside information, targeted, but not named “indiscretions from informed circles”, for example from entrusted MPs.

After repeated criticism of this practice, both by MPs and by the media, the German government has announced with the extension of the mandate for Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) that it will improve the information policy in agreement with the chairmen of the parliamentary groups.

In November 2018, the Bundeswehr started an extensive web series about the KSK, which initiated a paradigm shift in the association's public relations work after 22 years.

organization

The KSK is integrated into the structure of the Bundeswehr and is a regular unit of the army in terms of service.

The large association KSK is divided into the staff as well as command and support forces.

The KSK has a nominal strength of around 1,100 soldiers . The majority of these are deployed in the support, staff or telecommunications area, which is supposed to ensure the logistical supply, management support and operational readiness of the association. The actual command forces in the command core area form a small part that can only operate and function with the help of these support forces. The exact number of ready-commandos (command and command sergeant) than classified information classified. According to press reports, it is said to be between 400 and 500 commandos, a number which, however, was never reached due to a lack of qualified applicants.

The 2nd command company was dissolved on August 1, 2020 as part of the comprehensive reforms following an accumulation of right-wing extremist incidents . Personnel transfers from the KSK or to other areas of the KSK were ordered.

structure

The Special Forces Command (KSK) in Calw is divided into:

-

Special Forces Command (KSK)

Special Forces Command (KSK)

- Support staff

-

Training area (will be separated from the structure of the KSK in the future and subordinated to the training command)

Training area (will be separated from the structure of the KSK in the future and subordinated to the training command)

-

Development area

Development area

Staff and command support company Special Operations Component Command (SOCC) in Hardheim (was removed from the KSK structure in March 2021 and reports directly to the DSK )

guide

For operations, the forces of the KSK are subordinate to the special operations department in the command and control command of the German Armed Forces in Geltow near Potsdam , and in the case of multinational operations, tactically and operationally , a combined joint forces command post , a Combined Joint Forces Special Operations Component Command (CJFSOCC) . This ensures central management of all special forces within an operation.

KSK staff (command staff)

The command staff supports the commander in his leadership role and is responsible, among other things, for coordinating training, exercises and operations. He is led by the "Commander KSK", a brigadier general ( B 6 post ). The commander of the KSK also fills the position of " General Special Forces ". The command staff differs from a conventional brigade staff. Although it is also structured according to basic management areas, it also has the "Operation and Exercise" department, which is responsible for all training and exercise projects and also serves as a situation and planning center for the higher-level KdoFOSK, which it has operational responsibility for supported for KSK operations. A special feature are the language service integrated in the command staff and the psychological service , which is responsible for recruiting and aptitude tests as well as for looking after the soldiers before, during and after operations.

List of commanders

Previous commanders were:

| Surname | Beginning of the appointment | End of appointment |

|---|---|---|

| Brigadier General Markus Kreitmayr | June 26, 2018 | |

| Brigadier General Alexander Sollfrank | 23rd June 2017 | June 26, 2018 |

| Brigadier General Dag Knut Baehr | March 27, 2013 | 23rd June 2017 |

| Brigadier General Heinz Josef Feldmann | October 1, 2010 | March 27, 2013 |

| Brigadier General Hans-Christoph Ammon | June 29, 2007 | October 1, 2010 |

| Brigadier General Rainer Hartbrod | August 18, 2005 | June 29, 2007 |

| Brigadier General Carl-Hubertus von Butler | November 14, 2003 | August 18, 2005 |

| Brigadier General Reinhard Günzel | November 23, 2000 | November 5, 2003 |

| Brigadier General Hans-Heinrich Dieter | October 1, 1998 | November 23, 2000 |

| Brigadier General Fred Schulz | September 20, 1996 | September 30, 1998 |

Command forces

The command forces of the KSK consist of three command companies as well as a special command company and the special reconnaissance company.

Special command company

In October 2004 the special command company was set up. The special command company provides particularly skilled teams in the tasks of combat control (tactical airspace control), joint tactical fire support , counter IED and EOD (defense against threats from explosives), special demolitions and special service dogs. All soldiers' specializations are based on their basic qualifications as commandos. As a rule, older and experienced commando soldiers serve here, who support the command companies in operations and exercises if necessary. The special command company is usually the first and last in the area of operations, as their motto is: "First in, last out".

Special reconnaissance company

Specific reconnaissance skills are provided by the special reconnaissance company, depending on the situation and mission. Their staff consists mainly of commandos and specially selected and trained reconnaissance soldiers. They are able to work directly with the commandos, even under stress in special operations, and contribute their skills for drone-based, technical and multispectral reconnaissance as well as the detection and identification of NBC warfare agents or hazardous substances. In addition, the reconnaissance soldiers enable so-called “female engagement”, where the cultural conditions in the operational areas require it.

Command company

The manpower of a command company is estimated at around 100 soldiers, 64 of whom are emergency services. Because of the confidentiality, there is no official information on the exact numbers. Each of the three command companies consists of six platoons : a command group and five command platoons , each with a specialization that relates to the type of deployment and type of operation. This means the ability to reach an operational area in a certain way in order to carry out a command there (land, air, water and mountains):

- Special train for land / desert :