Altarabic deities

As old Arabic gods and goddesses gods of ancient Arabian religion called, worshiped by the Arab tribes before they confessed to Islam. According to Islamic tradition, the first Arabs were monotheists in the time of Ibrahim and his son Ismail . But later they would have assigned other gods to the true God ( shirk /شرك / 'Addition, polytheism') and began to venerate and sacrifice to them. Already in the language of the Koran there are two words, always in the plural, for the designation of idols: sanam, pl. Asnam /صنم, أصنام / ṣanam, aṣnām and wathan, pl. authan /وثن, أوثان / waṯan, auṯān .

The sources

Today there are only a few archaeologically and epigraphically usable evidence of these pre-Islamic deities. The primary sources for the documentation of ancient Arabic deities on the Arabian Peninsula are the material collections of Arabic epigraphy , which list the names of many deities, but without saying anything useful about their function and position in the religious life of the Arabs. Many of the finds - mostly rock inscriptions - contain pictorial representations, as the compilation of the inscriptions by Frederick Victor Winnett shows.

The oldest evidence of the ancient Arabic religion is an Assyrian text by King Assarhaddon (681–669 BC), according to which Ḥazaʾil, king of the Arab Qedar, asks the Assyrian king to send him back his idols, which the Assyrians had captured in the war. The gods are Atarsamain, Dai, Nuhai, Ruldaiu, Abirilu and Atarquruma. Only three of these deities appear in later sources, for example in inscriptions from Duma in the triad h-rḍw w-nhy w-ʾtrsm (Ruḍā and Nuhay and ʿAttarsamāʾ). The Greek historian Herodotus († 425 BC) mentions the Arab deities Orotalt (III / 8) and Alilat (I / 131, III / 8) in his histories and equates them with Dionysus and Aphrodite Urania .

Ibn al-Kalbi's "Book of Idols"

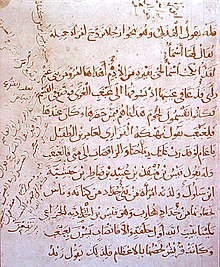

The most important author who wrote a work on the pre-Islamic religion and the idolatry of the Arabs is the historian and genealogist Ibn al-Kalbī (Hischam ibn Mohammed ibn as-Sa'ib al-Kalbi, * around 737 ; † 819 or 821 ). In his Kitab al-Asnam /كتاب الأصنام / kitābu ʾl-aṣnām / 'The Book of Idols ', he describes the ancient Arabic deities and the customs associated with them, mainly according to oral traditions of his time. The first additions to the basic work were entered at the end of the manuscript acquired and published by Ahmad Zaki Pascha (see below) in the early 12th century. Several Muslim historians evaluated and quoted this work well into the 13th century and provided it with marginal glosses in the manuscript available to us. Excerpts from it - even if only paraphrased - are also preserved in subsequent literature from the 12th and 13th centuries. The geographer and literary historian Yaqut (d. 1229) transferred most of Ibn al-Kalbi's "Book of Idols" into his geographical dictionary, divided into the individual names of the gods in the alphabetical order of his work.

In his work, Remains of Arab Paganism, which is still relevant today, the German orientalist Julius Wellhausen evaluated the information on pre-Islamic idol worship quoted by Yaqut after Ibn al-Kalbi and thus presented for the first time a valuable monograph on the ancient Arab deities of the pre-Islamic period. However, the original remained lost.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Egyptian researcher Ahmad Zaki Pascha managed to come across the only manuscript of Ibn al-Kalbi's "Idol Book" in the private collection of an Algerian scholar and to purchase it. He presented the hitherto unknown manuscript to the public for the first time at the World Congress of Orientalists in Athens in 1912. In 1914 the first edition appeared in a careful edition: Ibn el Kalbi: Le livre des idoles ( Kitab el Asnam ) . In the appendix to the edition (pp. 107–111), the editor lists 49 other idols that are not mentioned in Ibn al-Kalbi. The orientalist Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger obtained a faithful new edition as a reprint of this work with a German translation and a rich commentary: Das Götzenbuch. Kitāb al-aṣnām of Ibn al-Kalbī. Leipzig 1941. The quotations below from Ibn al-Kalbi were taken from this book.

The English translation of the work was provided by Nabih Amin Faris (Princeton 1952) with scientific comments. Wahib Atallah translated the book into French and commented: Les Idoles de Hicham Ibn al-Kalbi . Paris 1969.

The early excerpts from Ibn al-Kalbi's work in the writings of Arab genologists of the 11th and 12th centuries - but not the original published by Ahmad Zaki Pascha - were processed by the Iraqi scholar Mahmud Shukri al-Alusi محمود شكري الآلوسي / Maḥmūd Šukrī al-Ālūsī († 1924) in his now "classic" Bulugh al-arab fi ma'rifat ahwal al-'arab /بلوغ الأرب في معرفة أحوال العرب / Bulūġ al-arab fī maʿrifat aḥwāl al-ʿarab / 'the achievement of the goal by knowing the living conditions of the Arabs', printed in three volumes in Baghdad 1314 H. Reprint in Cairo 1342 H (3rd unaltered edition), a work, which today is one of the bibliographical rarities in the Orient because of its importance.

The book of idols of Ibn al-Kalbi is undoubtedly a valuable source in the history of religion. In the historically significant epoch of the transition from Jāhilīya to Islam in the 7th century, it "has a very important say in the problem of religious change". The representations are accompanied by numerous poems about the deities, whose origins, according to the current state of research, go back well into the pre-Islamic period. The book of idols is a fundamental source for understanding the ancient religious relationships of the Arabs in pre-Islamic times. The poems handed down by the author offer a very good insight into the primitive "customs of pagan Arabia, which pass on many old, characteristic forms of this religious level".

Another work from the 9th century is likely to have treated pre-Islamic idolatry, as the book title suggests, in great detail. The author was a certain 'Ali ibn al-Hussain ibn Fudail and his book was called:الأصنام وما كانت العرب والعجم تعبد من دون الله / al-aṣnām wa-mā kānat al-ʿarab wa-ʾl-ʿaǧam taʿbudu min dūni ʾllāh / 'The idols and what the Arabs and non-Arabs worshiped to the exclusion of God'. The Baghdad bookseller Ibn al-Nadim († around 995) still records this work in his "Index".

Ibn Ishaq's biography of the prophets

The Sira of Ibn Ishaaq is the oldest work on account of the life of Mohammed . It contains basic information especially about the pre-Islamic idols of the Meccans who lived in and outside the sanctuary of the Kaaba الكعبة / al-Kaʿba in Mecca and venerated by the polytheists throughout the Meccan period of prophecy - and then up to the conquest of Mecca in 630 by the Muslims of the Medinan community. These reports mainly focus on stories about the extermination of pre-Islamic deities in and around Mecca after the city was conquered in January 630.

The Islamic Universal History

Above all, at-Tabarī in his famous and comprehensive annalistic history of Islam cites messages in the tradition of his predecessors about the idol worship of the pre-Islamic Arabs. His work is now available in English translation. Other compilers such as al-Balādhurī in the 3rd and Ibn ʿAsākir in the 6th Muslim century (9th and 12th century AD) have not added anything new to the old content.

In this regard, the valuable information provided by the Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi (1364–1442) is an exception. The author narrates in his only handwritten accessible work of al-Khabar 'on al-bashar /الخبر عن البشر / al-ḫabar ʿani ʾl-bašar / 'The message (s) about humanity' some reports on the idols of the Medinese on the eve of Islam according to older sources from the city history of Medina, which Ibn al-Kalbi apparently did not know. He names the names of idols who were venerated by the Aus and Khazradsch tribes and in their sub-tribes. The cult of some idols was limited to individual families.

The history of the city of Mecca

The oldest surviving work on the history of Mecca goes back to Al-Azraqī († 837):أخبار مكة وما جاء فيها من الآثار / aḫbār Makka wa-mā ǧāʾa fī-hā min al-āṯār / 'The history of the city of Mecca and its monuments'. It was first published by the German orientalist Ferdinand Wüstenfeld in the adaptation of his grandson Muḥammad ibn ʿAbdallāh ibn Aḥmad al-Azraqī († 865) . The author provides numerous pieces of information about the cult of idols that were still circulating in the Meccan scholarly life in his time, but which Ibn al-Kalbī has not received. The legendary stories about the origin of the Meccan sanctuary in the pre-Islamic period are presented in partly controversial versions and from the perspective of Islamic monotheism .

The history of idolatry among the Arabs

Since the Arabian Peninsula , with the exception of southern Arabia , has hardly been developed archaeologically and the idols were destroyed with the rise of Islam in the time of Muhammad, the emergence of the idol cult can only be based on legendary reports from the pen of Islamic genologists, above all Ibn al-Kalbi and Ibn Ishaq. In addition, there are some fragments of tradition in the Koran exegesis about those Koran verses that speak of the pre-Islamic idols and the pagan customs of the Arabs.

In sura 3 , verse 96-97, the house of God in Mecca - the Kaaba - is the original center of monotheism:

“The first (God's) house that was erected for people is the one in Bakka (di Mecca), (erected) for the blessing and guidance for people all over the world. There are clear signs in him. (It is) the (holy) place of Abraham. "

According to the Koran and the Islamic prophetic legends (qisas al-Anbiya '), the monotheism founded by Abraham and Ishmael has been falsified by the Arabs themselves and converted into the worship of idols. For this, the Islamic historiography makes a certain 'Amr b. Luhaiy from the Khuza'a tribe, whose identity and historicity cannot be verified. “The first who changed the religion of Isma'il (salvation be upon him) and set up the idol stones (...) was ʿAmr b. Rabīʿa, di Luḥaij (…), and he is the father of Ḫuzāʿa. "

The types of bloodless animal consecration mentioned and condemned in sura 5 , verse 103, are traced back to this 'Amr ibn Luhayy as well as the five idols at Jeddah mentioned in sura 71 , verse 23, which' Amr is said to have introduced into Mecca (see below). He is said to have brought more idols from Mesopotamia to Mecca and set up five of them in Mina , which was sanctioned by Mohammed in the early 7th century as a station of Islamic pilgrimage . Hubal, the main god of the Meccans (see below) is said to be 'Amr b. Luhayy from Balqa ' .

Sacred places, sacred stones, sacred trees

Holy places

These idols became holy precincts الحمى, حمى / ḥiman, det. al-ḥimā , - derived from the common Semitic root ḥ - m - y "protect, guard - consecrated", where there was often a spring or a well in which no tree was felled and no animal was allowed to be killed. Animals that grazed in such a district succumbed to deity. The sacred area, the Temenos , is the older form of idol worship; the nomads only built a house (bait) for the gods later. Both gods and demons dwell in the sanctuaries. The Ḥimā is therefore taboo in two ways . The Quraish have declared a whole mountain gorge to be Ḥimā for the deity al-'Uzzā . Hima districts have been demarcated and marked with stones to draw attention to the taboo. Even the Prophet Mohammed declared a pasture area for "Ḥimā", where only camels and horses of the Muslims that were used in the war and raids were allowed to graze. The free grazing cattle of the Muslims were forbidden. As a result, an old custom from the pre-Islamic period was sanctioned and anchored in Islamic jurisprudence as a constitutional norm by the statement: "No Ḥimā except for God and his messenger" and included in his hadith collection as a prophetic saying by al-Buchārī . It still exists today in the Asir and in the Tihama those Ḥimā areas that are only allowed to be cultivated to a limited extent (e.g. beekeeping). Although they are hardly of any religious significance, they form a kind of protection reserve in the highly sensitive Arab vegetation, which is important for the survival of the tribe. They are now accepted by the government as nature reserves.

Holy stones

The Arabs had no images of gods, but worshiped holy stones ( baityl ), which mostly remained unprocessed. These were touched, kissed and circled: after Ibn al-Kalbi, the circuit was called tawafطواف / ṭawāf - as in Islam - or, especially in pre- and early Islamic poetry, dawar.دوار / dawār .

Such stones were called al-ansab الأنصاب / al-anṣāb ; Ibn al-Kalbi writes: “The Arabs had dust-colored stones that they had set up. They circled around and sacrificed near them. They called her al-anṣāb ”. In the case of the cult stones, animals were sacrificed and those were sprinkled or smeared with blood. Such stones are already described by Herodotus .

The Kaaba (الكعبة) in Mecca - built by Ibrahim according to Islamic beliefs and allegedly of heavenly origin - was already an important shrine in pre-Islamic times. Muhammad ibn Saʿd reports that the stone was originally worshiped on Mount Abu Qubais near Mecca; only four years before Muhammad's first revelations did the Quraish put the blackened stone in the city. The Koran exegete Mujāhid ibn Jabr explains the color of the stone with the custom of the polytheists, who used to smear the stone with blood. Thus this stone fulfilled the function of other ansab . Within the holy area there was not only the famous black stone, but also the figure of Hubal made of red carnelian and the holy Zamzam well . The "ansab" were rough stones that were set up in private houses / tents; little by little they have been replaced by idols (ṣanam / aṣnām) as sculpted statues. According to al-Azraqi, on the eve of Islam there was no house in Mecca without an idol.

According to the report of al-Maqrizi (see above), there were idols in Yathrib who were worshiped in public by the entire tribe or by extended families of the tribe. They were at the meeting place, the so-called madschlis مجلس / maǧlis , set up under the supervision of the tribal chief. Idols for personal use were made and sold in pre-Islamic Mecca.

Sacred trees

Not only stones and unusual rock formations, but also trees and springs enjoyed special reverence among the pre-Islamic Arabs. The goddess al-ʿUzzā lived in three samura trees. A sacred date palm stood in Najran and was hung with clothes, as was another tree near Mecca. Some idols in the form of imposing trees were decorated and hung with weapons, ostrich eggs or colorful scraps of fabric. It was called Dhāt Anwāt: a tree that is hung. The tree mentioned in sura 48 , verse 18 at al-Hudaibiya, where Mohammed concluded the well-known, temporary armistice with the Meccans , soon became the object of worship. The second caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb had the tree felled so that it would not be worshiped like the idols al-Lāt and al-ʿUzzā.

Pre-Islamic rituals in holy places

Oaths by the pre-Islamic Arabs took place in the holy places where the idols were native: z. B. in the Hima area of al-Lāt , Manāt , al-ʿUzzā and between Safa and Marwa. Already in the Jāhilīya one swore on the Kaaba, the highest pagan sanctuary of Mecca. Corresponding lines of verse by the pre-Islamic and early Islamic poets show that in the pre-Islamic period it was customary to take vows and oaths both at the place and at the sanctity of places where idols were located. Such places of sacrifice, without naming specific idols, serve as oaths: "I have sworn - at the place where the sacrificed animals are offered" and: "I have sworn - by him to whom the sacrificed animals are brought" .

Traces of the old, pre-Islamic stone cult are in Islam, combined with the monotheistic "Abraham legend", through the central meaning of the "black stone" al-hadjar al-aswad /الحجر الأسود / al-ḥaǧaru ʾl-aswad and the "happier stone", al-Hajar al-as'ad, also located on the eastern corner of the Kaaba /الحجر الأسعد / al-ḥaǧaru ʾl-asʿad , who is only touched but not kissed, demonstrable.

The pre-Islamic Arabs circumnavigated their sanctuaries barefoot or naked. It was not allowed to carry out the circulation in one's own clothes, as these have also become taboo through contact with the saint and thus had to be left behind in the sanctuary. It is true that Islam sanctioned the Tawaf as part of the pilgrimage ritual, but rejected the type of circulation described above in sura 7 , 28-30 and ordered in the following verse 31: “You children of Adam! Put on your jewelry at every place of worship, and eat and drink! And don't be wasteful ” . In interpreting these verses of the Koran, the Koran exegetes unanimously report that the men circulated naked during the day and the women during the night. The phrase "put on ... your jewelry" interprets the exegesis accordingly: "put on your clothes". In March 631, on the pilgrimage to Mina led by Abū Bakr - according to Ibn Ishaq's prophetic biography - Mohammad announced: “No unbeliever ( kāfir ) will enter paradise, no polytheist ( muschrik ) will make the pilgrimage after this year and around that House (Kaaba) (allowed to walk) naked… ” With this, the pre-Islamic custom was finally abolished both by the Koran and by the above prophetic words.

The local historian of Taif al-Husain ibn Ali al-Udschaimi, who died in 1702, reports on traces of circulation in venerated places in the secular area , whose work on contemporary news about the city was published by one of his descendants in 1847. The inhabitants of Taif and its surroundings not only circulated around the graves of their ancestors, but also around the grave of the Koran exegete of the early Islamic period ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbbās, who was venerated there.

During the occupation of the Great Mosque in 1979 , a group of rebels holed up in the Kaaba, which was overpowered with the help of French special forces. When a bomb exploded, the floor of the building was torn open; several idols emerged from it, which the Saudi authorities quickly removed. Nothing is known about their whereabouts.

Djinn and demons

It can be deduced from some verses of the Koran that there were Arabs who worshiped the jinn in the time of Muhammad . The unbelievers have “made them partakers of God” ( sura 6 , verse 100) or they have “established a kinship between him (God) and the jinn” ( sura 37 , verse 158). The Islamic tradition also has something to say about them. The Banu Mulaih from the Chuza'a tribe worshiped the jinn - Ibn al-Kalbi reports. “Spirits and gods do not differ in their nature, but only in the way they relate to humans; The spirits are shied away from and their dwellings are avoided, the gods are met with confidence and they go to their dwellings specifically in order to worship them and obtain help ” . In the Qur'an it is not the existence of such beings in the beliefs of the Arabs that is disputed, but their divine or extraterrestrial nature. It should be noted that the jinn - in contrast to the ancient Arabic deities - are still alive in contemporary popular belief. Islamic elements are now used as a means of defense against these "evil spirits": Koranic verses for incantations and amulets with Islamic motifs and magic spells.

Pre-Islamic deities

- Allah (الله), also ʾIlāh and Lāh "(the) God". He was already the main god among the pre-Islamic Arabs.

- Ar-Rahmān (الرحمن) was an equal name for the main god in al-Yamāma and in central Arabia. The distinction between Allah and Ar-Rahman is still handed down in Islamic times. In Muhammad ibn Saʿd there is a line by the poet Bishr ibn mAmr al-Jārūd from al-Yamāma, in which it says: “We are satisfied in every way with Allah's religion. We are content to have Allaah and (!) Ar-Raḥmān as Lord. "

- Al-Lāt (اللات, اللت), also ʾIlāt and Lāt "(the) goddess". This goddess already appears in Herodotus as Alilat (Άλιλάτ), who was compared to Urania . The Palmyrene ruler Vaballathus وهب اللات / wahb allāt / 'the gift of al-Lāt' was called in Greek Athenodoros "gift of Athena ", which suggests that both goddesses are equated. A white granite block was consecrated to the deity al-Lāt in al-Ṭāʾif , where she was also called "ar-Rabba" (the mistress). The name appears several times in ancient North Arabic inscriptions: in Safaite rock inscriptions she is called upon to grant booty and security: “ʿAwīdh b. Ḥunain b. Khalaf of the tribe of Qamar. And he has arrived (here). And, O Allāt (grant) plunder and security. And blind him who damages the inscription. ” The Safaite origin of the deity is also assumed in recent research. Ibn al-Kalbi writes: “Al-Lāt was in at-Ta'if. She is younger than Manat. Al-Lāt was a square boulder that a Jew used to pound grits on. Their keepers were the Banū 'Attāb ibn Mālik of the Thaqif tribe. They had built a building over her. The Quraish and all Arabs worshiped them ... The worship of al-Lāt continued until the Thaqif tribe converted to Islam. The Messenger of God (God bless him and give him salvation) sent al-Mughira ibn Shu'ba; he destroyed them and burned them with fire. ” Accordingly, the Arabs called the Jew, who used to pound porridge with the deity, al-Lātt and thus established a connection with the name of the idol (Part. Act. of arab.laṯṯaلث, لت / 'Chop / grind grain').

- The idol of the goddess was destroyed by Mohammed and his followers after the capture of Mecca. The first mosque in the settlement was built in its place. Their Himā district was retained by Mohammed and sanctioned in Islam. But one has not forgotten the deity. Because the British explorer and orientalist Charles Montagu Doughty reported in his famous book: Travels in Arabia Deserta (Vol. II. 511 and 515-516) in the late 19th century about boulders at at-Taif, which the residents at that time al-'Uzzā , al-Lāt and Hubal and from whom they secretly sought help in cases of illness.

- al-ˤUzzā (العزّى,the strongest'). She was compared to Aphrodite in a Nabataean- Greek inscription on the island of Kos . Their sanctuary in Suqām in Wadi Ḥurāḍ near Nakhla consisted of three samura trees (umbrella acacia) and a holy stone with a cave into which the blood of the sacrificed animals was poured, which Ibn Hisham reports in his prophet biography (sira) according to Ibn Ishāq White. The Ghatafan and other tribes near pre-Islamic yathrib worshiped them. She was also venerated by the Lachmids of Hira . King Mundhir IV swore by her, his predecessor Mundhir III sacrificed four hundred captured nuns to her and, on another occasion, the son of his opponent whom he had captured. Ibn al-Kalbi writes: “She is younger than al-Lāt and Manāt. ... The Arabs and the Quraish named (their children) by the names' Abd al-'Uzzā. She was the highest idol among the Quraish. They used to visit her, bring her presents and make sacrifices at her place. We heard that the Messenger of God (God bless him and give him salvation) mentioned them one day; he said: 'I offered a reddish white sheep to al-'Uzzā at the time when I was still professing my people's cults'. The Quraish used to orbit the Kaaba saying: “By al-Lāt and by al-'Uzzā and by Manāt, the third, the other! They are the very highest swans and one can hope for their intercession (with God) ”. The Quraish had created a himā for her, in a mountain canyon of Wadi Hurād, called Suqām. They created a side piece to the Haram, the holy precinct of the Kaaba ... al-'Uzzā had a slaughtering site where their victims were slaughtered; his name was al-Ghabghab. ” After the conquest of Mecca, their cult disappeared, as did the proper names formed with 'Uzzā. Remnants of their veneration were still observed in the 19th century at al-Ta'if (see above: al-Lāt).

- Manawat, Manāt (منوة, مناة,Fate'). In ancient times she was equated with Tyche and Nemesis . A large black stone dedicated to her was on the coast near Qudayd (between Medina and Mecca ). Ibn al-Kalbi writes: “When 'Amr ibn Luhayy had introduced idolatry, the Arabs now professed the cult of idols. They served them and made them gods. The oldest of them all was Manat. The Arabs used the names' Abd Manāt and Zaid Manāt. "

- Hubal (هبل) He was worshiped by the North Arabian Nabataeans , as attested by an inscription in which he is mentioned with two other North Arabian deities. The Islamic historians also point to the North Arabian origin of Hubal. Etymologically, the name cannot be derived from Arabic. Research suggests that the name is related to ha-Ba'al . In Mecca he was worshiped in the Kaaba and he was the lord of the seven oracle arrows there. Ibn al-Kalbī writes: “As far as I have heard, Hubal was of red carnelian, in human form, with a broken right hand. The Quraish had got him like that; but they made a hand of gold for him. He was inside the Kaaba. ” Abū Sufyān ibn Harb praised him as the main god of the Meccans on the day of his victory at Uhud :“ High Hubal! ”That is, your cult be exalted. According to Julius Wellhausen's assumption, its importance for the Meccans among the idols and its worship in the Kaaba itself may have paved the way to a generally recognized, universal God (Allah) in pre-Islamic beliefs and rites.

- Isāf and Nāʾila (إساف ونائلة). Pre-Islamic pilgrim couple who committed fornication in the Kaaba and were therefore petrified. Ibn al-Kalbī writes: “They came to Mecca as pilgrims and found a lonely place in the temple and were ignored by the people. Then he fornicated her in the holy house, whereupon they were changed into two stones. ”One stone was set up and worshiped at the Zamzam well , the other at the Kaaba. The Quraish made offerings there. The Meccan local historian Al-Azraqī (d. 837) reports the following in his city history of Mecca: “They were then removed from the Kaaba. One was set up at (the hills) as-Safa, the other at al-Marwa. They were put there so that people would remember them and be deterred (from doing) what these two committed and so that they could see what became of them. After a while they were touched; those who stopped at as-Safa and al-Marwa (during the pilgrimage ceremonies) touched them. So they became idols to be worshiped. ” Abū Sufyān b. Ḥarb , one of Muhammad's most famous adversaries, sacrificed hair to these idols shortly before the Muslims conquered Mecca, slaughtered animals for them and vowed to serve them until his death. The house of Al-Arqam ibn Abī l-Arqam , where Mohammed found refuge during the Meccan period of prophecy, was near Isāf at as-Safā. After the removal of the idols, the two hills remained destinations of pilgrimage even in Islam. Because as-Safa and al-Marwaالصفا والمروة / aṣ-Ṣafā wa-ʾl-Marwa , connected with the pre-Islamic custom of walking between the two hills where the idols stood, have got their permanent place in the Islamic rite of pilgrimage, even sanctioned by revelation. In sura 2 ( al-Baqara ), verse 158, which refers to the Muslims' concerns about continuing to take part in the traditional course between the two hills in the Islamic pilgrimage ritual, it says:

- “As-Safā and al-Marwa are among the cult symbols of God. If one goes on the (great) pilgrimage to the house (the Ka'ba) or the visiting trip ( 'umra ), it is not a sin for him to socialize with them. "

- The Koran exegesis sees in this verse the addition to the command to deal with the Kaaba in sura 22 , verse 29: … and to deal with the old (venerable) house.

- The concerns of the Muslims handed down by the Koran exegetes and traditionalists against the further exercise of the generally practiced pre-Islamic custom of running or circulating on the two hills has thus been dispelled by the above verse from the Koran. Mohammed has affirmed this pre-Islamic custom through his own words as part of the pilgrimage ceremonies, as Sunnah : "God does not consider your pilgrimage or your little pilgrimage ('umra) to be complete as long as you do not make the circuit around the two (hills)." The little pilgrimage ('umra) was made by Mohammed with his followers before the conquest of Mecca, at a time when the pagan idols were standing with Safa and Marwa and when the prophet was offering sacrificial animals. Islam relates the cultic course between the two hills to Hāǧar , Ismail's mother, who had desperately looked for water and finally found the Zamzam well.

- al-Khamīs (الخميس) was an idol worshiped by the Banū Sulaim , who had good trading contacts with Medina, and by the Khazradsch . As with the deity al-Manat, an oath was taken with al-Khamis.

- Manāf (مناف) A Greek inscription invokes the god Zeus Manaphe (Ζεῦ Μαναφε). According to at-Tabarī , he is said to have been the chief god in Mecca. The Quraish thus formed theophore names, such as' Abd Manāf; he was the great-great-grandfather of the founder of the religion, Mohammed. His worship is also documented in North Arabic inscriptions.

- Quzaḥ (قزح) God of thunder , whose name in arab. Word qaus quzaḥ (قوس قزح'Rainbow') is preserved. He was worshiped on the mountain of the same name near al- Muzdalifa , where a constant fire burned. The mountain is still important in pilgrimage today . Today there is a brightly lit mosque on the mountain. Yaqut reports in his Geographical Dictionary (sn q - z - h) that Quzaḥ is a hill near al-Muzdalifa, where the Quraish created a Ḥimā district in pre-Islamic times. Islam kept the name; it is the place where the prayer leader ( imam ) stands during the pilgrimage ceremonies.

- Nuhaj Šams (شمس,Sun'). Sun god. In Thamudic inscriptions he is invoked with nhy šms ʿly (Nuhaj, high sun). The god is called Nuḫāi in Assyrian texts.

- Nuhm (نهم) was an idol of the Muzaina tribe south of Medina. After him they coined the name ʾAbd Nuhm. According to a verse in Ibn al-Kalbi, the meat of the sacrificial animals presented there should not be eaten.

- Saʿd (سعد,Luck'). A large rock in the coastal area of Jidda , the port city of Mecca, was dedicated to him, which belonged to two Kinana families . It was customary to offer animal sacrifices with him and to pour the blood on the idol stone.

- al-Fals (الفلس) A human-like red rock in southern Arabia was consecrated to him and a king of Ġassān is said to have girdled him with the two swords Miḫḏam and Rasūb. The holy precinct (al-ḥimā) of the deity was inviolable as a place of asylum.

- Ruḍāʿ (رضاء,Favor'). Goddess of Banu Rabīˤa. Possibly it was already called Orotalt (Όροτάλτ) by Herodotus , who compared it to Dionysus . She was also known by the Assyrians , who called the Arab deity Ruldāiu. In Thamud , the deity, whose gender is not clear, received firstfruits and implored rain. In Safaite inscriptions , this deity is invoked several times to guarantee personal safety: “By Ṣārid b. Ādam b. Ẓāʿin of the tribe of (...). And he set it (up). And, O Ruḍā, (grant) security this year from enemies. ”In Palmyra it appears in personal names .

- ḏū-l-Šarā (ذو الشرى'That of Šarā'). Nabatean god identified with Dionysus. A sub-tribe of the Azd worshiped him and camped on his Hima: Ibn al-Kalbi quotes a line of verse: "We camped around in front of Ḏū ʾš-Šarā / and our strong, mighty army split the heads of the enemies." Ibn Hischam in the biography of the prophet of Ibn Ishaq a Kaaba with a sacred area (Ḥimā). Both in Nabataean and in Arabic theophore names were formed with it: ʿAbddūsharā, Taymdūsharā or ʿAbd dhī Sharā. In Safaite inscriptions this deity appears - together with al-Lāt - and is asked to guarantee security: “(…) b.ʿĀmir b. Tiyāshat b. ʿAtīq b. Badan b. Ẓānin b. Ḥarām b. ʿAwīdh b. Wahabʾel and (…) O Allāt and Dhū Sharā (grant) security, but the evil eye (be) on the loved one of him who effaces the inscription. “ Theodor Nöldeke assumes with J. Wellhausen that the name was originally a landscape designation is.

- Dhū l-Chalasa (ذو الخلصة) He was venerated as a white stone near Tabāla, between Mecca and Yemen. A kind of crown was carved on the stone. Ibn al-Kalbi writes: “One of them (that is, of his devotees) said: 'If you, o Ḏū ʾl-Ḫalaṣa, who were obliged to vengeance, were like me, and if your father were the buried, then you would have yourself not forbidden to kill the enemy in falsehood. ' - This man's father had been killed. He wanted to satisfy his need for revenge, so he came to Ḏū ʾl-Ḫalaṣa and shook the oracle arrows in front of him, but he drew the forbidding arrow. Then he composed the verses mentioned ”. The famous pre-Islamic poet Imruʾal-Qais (d. Before 550), the son of a prince of the Kinda tribe , who wanted to take revenge for the murder of his father and described the event in a well-known poem, questioned the arrows of this idol. But when he drew the arrow with the prohibition (an-nahy) , he broke it and continued to prepare for the blood revenge. Ibn al-Kalbi writes: “Each time he drew the 'forbidding' arrow. Then he broke all three of them and struck the idol in the face with them, saying: 'May you bite your father's limb! If your father had been killed, then you would not have held me back. '”According to a report by Ibn Sa'd , a disciple of al-Waqidi, the sanctuary was called the Ka'ba al-yamāniyya (the Yemeni / southern Ka 'ba) to distinguish it from the Ka'ba asch-shāmiya (the Syrian / northern) Ka'ba. At the time of Ibn al-Kalbi, the stone of this idol formed the threshold of the mosque of Tabāla. The deity was also known in the Taif area , where it was worshiped by the Banu Zahran and Daus. The editor of al-Azraqi's above-mentioned city history of Mecca, the Saudi scholar Rushdi al-Salih reports in the appendix of this work on the existence of this deity in the early 20th century as follows: “When his Majesty Abd al-Aziz al-Faisal Al Sa ' ud King of Saudi Arabia defeated the Hidjaz in 1343 H. he appointed Abd al-Aziz ibn Ibrahim as governor of the Taif region. He commissioned him to subjugate the tribes residing in the mountains of the Hidjaz with an expedition of his majesty. After the troops defeated the tribes of the Banu Zahran who lived in the wadi named after them, they moved on in the II. Rabi '1344 H. in the direction of the mountainous landscape of the Banu Daus. In the village called Tharuq, the walls of the building of Dhu 'l-Chalasa were still preserved. Next to it stood the tree (called 'al-'Abla'). The expedition burned the tree and destroyed the building. The rubble was thrown down into the valley. One who accompanied the expedition reports that the construction of Dhu 'l-Chalasa was so powerful that more than forty men were able to move a single stone from it. Its stability is evidence of great experience and knowledge in construction. "

- Dhu'l-kaffain ذو الكفين / 'The two-handed' was another idol of the Banu Daus. When they were converted to Islam, Mohammed sent a member of the tribe to burn the idol.

- Wadd (ود,Friend'). Sabaean god who was also worshiped by the Arabs. In Ibn al-Kalbi he is described as follows: “Wadd was the statue of a man, tall, like the greatest of men. Two robes were carved on him; one garment was worn as izār, ie as an overgarment, and the other as ridā, ie as an overgarment. He was girded with a sword and carried a bow on his shoulder. In front of him he had a lance with a flag and a leather quiver with arrows in it. ”It should be noted that the two garments of the Muslim pilgrim in the state of ihram have the same names. At another point in the book of idols , the author mentions that this deity was also worshiped by the calf tribe in the north of the Arabian Peninsula. A poet not mentioned in detail is said to have spoken, probably already in the early Islamic period: “Wadd keep you alive; Because we are no longer allowed to play with women, because religion has become serious. "There were also festivals at the pilgrimage sites with the deity Wadd, who can mean both" love, affection "and" lover, friend ", common. The line of verse shows "how Islam intervened sharply and harshly." Nöldeke has already emphasized that the name Wadd in Islamic literature was replaced by the term rabb (Lord / Lord God) in the monotheistic sense.

- ʿĀʾim (عائم) was a deity probably of Nabataean origin from the area of Hauran , who was also worshiped by the Azd. In Ibn al-Kalbī there is a line of verse by the poet Zaid al-Ḫail, Zaid ibn Muhalhil, the head of the Banū Nabhān, who is said to have accepted Islam shortly before his death, in which he swears by this deity: "Please report, Who did you meet when you put them on the run without even knowing what their characteristics are. No, by ʿĀʾim! "

- ʾUmyanisu (عميانس) was an idol worshiped by the Yemeni Khaulan tribe between Sanaa and Marib . Ibn al-Kalbī reports: "They allotted him a portion of their cattle and their harvest, which (of equal size) should go to him and Allah (he is great and exalted), as they claimed." This pagan custom relates to this also sura 6 , verse 136: “And they (that is, the unbelievers) have given God a share of what he has grown in grain and cattle. And they say: 'This is due to God' - (see above) according to their assertion - and this to our partners. ”Not only in Ibn al-Kalbi, but also in the Koran exegesis, this verse is explained with reference to the custom described above. The Banu Khaulan used to implore the idol in the drought with sacrifices for rain. This custom is in Islam through the "rain prayer" salat al-istisqa ' /صلاة الاستسقاء / ṣalātu ʾl-istisqāʾ has been sanctioned.

- al-Uqaiṣir (الأقيصر). The etymological origin and meaning of the name are in the dark. Yaqut understands the name form as a diminutive of aqṣar "the shortest, the smallest". This idol was worshiped by the northern Arabs , the Quḍāʿa and Ġaṭafān ; they made a pilgrimage to him, circled him and offered him hair and food. Ibn al-Kalbi quotes a line in verse: “I solemnly swear by the holy stones of al-Uqaiṣir / and at the place where the foreheads and the lice are shaved off . “Oaths were also common in other holy places, or in the name of the gods. In Islam, taking the oath (ḥilf) at the Kaaba and at Muhammad's minbar is the most important form of the oath.

- Suʿair (سعير) was the idol of the tribe ʿAnaza, who used to offer animal sacrifices there and circumnavigated the idol. The ʿAnaza still exist today.

- Suwāˤ (سواع) He had a sanctuary at Yanbuˤ, the port of Medina.

- Nasr (نسر,Eagle'). Sabaean god who was also worshiped by the Arabs.

- Wadd (ودّ): see above;

- Yaghūth (يغوث); "Helper"

- Yaʿūq (يعوق);

These last five idols have found their place in the pre-Islamic ancestral cult . Because in an isolated tradition Ibn al-Kalbi reports about them as follows:

- “Wadd, Suwāʿ, Yaghūth, Yaʿūq and Nasr were pious people. They died in the same month. Her relatives were very sad. Then a man from the Banū Qabīl said: 'O my fellow nationals! Shall I make five idols for you in their own image? But of course I can't breathe life into them. ' They replied: 'Yes!'. So he carved five idols for them in their own image and set them up for them. Now everyone used to come to his brother, to his uncle and his cousin, to worship them and to walk around them ... Then came another generation that honored idols with even more worship than this first. "

The Arabs carried the idol Yaghuth with them in their battles; Ibn al-Kalbi has received two lines of verse about it: “Jaġūṯ went with us against the Murād. / And we fight against them before dawn. ”Yaghuth theophore was used to form names such as ʿAbd Yaghūth“ Servant of Yagūth ”. The brother of Āmina bint Wahb , the mother of the Prophet Mohammed, bore this name.

With Wadd, the Arabs also formed theophoric names such as' Abd Wadd "servant of Wadd". Their story is moved to the time of Noah in the Koran ; Sura 71 , verses 23-24 prove that their names and meanings must have been alive in the time of Muhammad: “And they said: 'Don't give up your gods! Don't give up Wadd, Suwāʿ, Yaghūth, Yaʿūq or Nasr! And they have misled many. '”This sura, which seems to be a fragment and in which Noah polemicizes against idols, linked traditional Islamic literature with the history of the Flood and with its own Arab legends about the introduction of idol worship. For it was the aforementioned 'Amr ibn Luhaiy who dug up these five idols on the seashore of Jeddah and brought them to Tihama. This legendary person as the alleged father of idol worship and his fate were long remembered by the Arabs. For the Prophet is allowed to speak as follows: “Hell was brought to me and I saw 'Amr, a short man with fair skin and blue eyes, who dragged his entrails in Hellfire ... He changed the religion of Ibrāhīm and asked the Arabs to worship him Idols on. "

The idol worship in the hadith

In the traditional literature , the unreserved rejection of the pre-Islamic idols (ṣanam / aṣnām) can be proven in many sayings ascribed to the prophet. In the chapters of the hadith the trade in wine, pork, the meat of dead animals and idols is prohibited. According to the Koran exegesis ( Tafsīr ), sura 17 verse 81 of the Koran is said to have originated in connection with the destruction of the 360 idols that were set up in and near the Kaaba on the occasion of the conquest of Mecca (630): "The truth is (with Islam) come, and lies and deceit (of unbelief) (i.e. what is void) are gone. Lies and deceit (always) vanish. ”Accordingly,“ lies and deceit ”is briefly equated with shirk in the Koran exegesis .

The invocation of the deities, which was already in use in pre -Islam, is replaced by the strictly monotheistic Islam with the invocation of the Lord of Lords (rabbu 'l-arbāb), who "has conquered all idols and idols in the land".

List of ancient Arabic deities

| God, idol | Arabic | tribe | Brief description | Ibn al-Kalbi | Koran |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Allah ʾIlāh, Lāh |

الله ,(the God' | Arabs | Pre-Islamic main god | ||

|

al-Lāt ʾIlāt Lāt |

اللات, اللت ,(the goddess' |

Arabs | white granite block in al-Ṭāʾif | al-Lāt | Sat. verses |

| al-ʿUzzā | العزّى ,the strongest' | Arabs | Sanctuary in Suqām in Wadi Thurāḍ | al-ʿUzzā | Sat. verses |

| Manawat, Manat |

منوة مناة ,Fate' |

Arabs | black stone on the coast near Qudayd (between Medina and Mecca ) | Manah | Sat. verses |

| Hubal | هبل |

Quraish Nabataeans |

Lord of the 7 oracle arrows in the Kaaba , Abū Sufyān ibn Harb : main god of the Meccans |

see al-ʿUzzā |

|

| Isāf and Nāʾila | إساف ونائلة | Quraish | Pre-Islamic pilgrim couple who were petrified in the Kaaba for fornication , set up at the hills of al-Safa and al-Marwa and venerated by the pilgrims. | Isaf and Na'ila see al-ʿUzzā |

Sura 2: 158 , Hajj |

| Manāf | مناف | Quraish | at-Tabarī : The most distinguished god of Mecca | see al-ʿUzzā |

|

| Quzaḥ | قزح | God of thunder , who was worshiped on the mountain of the same name near Muzdalifa . Muzdalifa is now part of Hajj . | |||

| Nuhay Šams | شمس ,Sun' | Thamud | Sun god | ||

| Nuhm | نهم | Muzaina | south of Medina | Nuhm | |

| Saʿd | سعد ,Luck' | Kinana | big rock at Jidda | Saʿd | |

| Sūwāʿ | سواع | Hudhayl | Sanctuary at Yanbuʿ, the port of Medina | Suwaʿ | Noah |

| al-Fals | الفلس | Tayyi ' | red rock in southern arabia | al-Fals | |

| Ruḍā | رضى ,Favor' |

Rabiʿa Thamud |

see al-ʿUzzā |

||

| ḏūš-Šarā | ذو الشرى 'That of Šarā' | Nabataeans | equated with Dionysus | Dhu ash-shara | |

| ḏū l-Ḫalaṣa | ذو الخلصة | white stone at Tabāla between Mecca and Sana'a | Dhu l-Chalasa | ||

| Wadd | ود ,Friend' |

Sabeans , Mineans |

Wadd | Noah | |

| Nasr | نسر ,Eagle' | Sabeans | Nasr | Noah | |

| al-Uqaiṣir | الأقيصر |

Northern Arabs , Quḍāʿa Ġaṭafān |

al-Uqaysir | ||

| Suʿair | سعير | ʿAnaza | Su'ayr | ||

| Yaghuth | يغوث ,he helps' | Yaghuth | Noah | ||

| Ya'uq | Ya'uq | Noah |

literature

- The book of idols Kitāb al-aṣnãm of Ibn al-Kalbī . Translation with introduction a. Comment from Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger. Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1941.

- Ibn al Kalbi: Le livre des idoles . (Kitab el asnam). Texts arabe. Ed. Ahmed Zeki Pacha. 2nd Edition. Cairo 1924.

- Toufic Fahd: Le Panthéon de l'Arabie centrale à la veille de l'hégire. Paris 1968.

- Hans Wilhelm Haussig , Dietz Otto Edzard (ed.): Gods and myths in the Middle East (= dictionary of mythology . Department 1: The ancient civilized peoples. Volume 1). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1965.

- Gerald R. Hawting: The Idea of Idolatry and the Emergence of Islam: From Polemic to History. Cambridge University Press 2004.

- Joseph Henninger: Belief in ghosts among the pre-Islamic Arabs . In: Festschrift Paul J. Schebesta. (Studia Instituti Anthropos. Vol. 18). Vienna-Mödling 1963. pp. 279-316.

- ders .: Something about ancestor cult among Arab Bedouins . In: Wilhelm Hoenerbach (Hrsg.): The Orient in Research. Festschrift for Otto Spies on April 5, 1966. pp. 301–317. Wiesbaden 1967.

- Ludolf Krehl : Religion of the pre-Islamic Arabs . Leipzig 1863.

- Maria Höfner : The pre-Islamic religions of Arabia. In: Same, Hartmut Gese , Kurt Rudolph : The religions of Old Syria, Altarabia and the Mandaeans. Stuttgart 1970, pp. 233-402.

- Susanne Krone: The Arab deity al-Lāt . Heidelberg Oriental Studies 23. Peter Lang 1992.

- Henry Lammen : Le culte des Bétyles et les Processions Religieuses chez les Arabes Préislamiques. In: Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archélogie Orientale. Volume 17. Cairo 1920. See also: H. Lammen: L'Arabie occidentale avant l'Hègire . Beirut 1928, pp. 100-180.

- Theodor Nöldeke : History of the Qorāns . 2nd edition edited by Friedrich Schwally. Part One: On the Origin of the Qorān. Leipzig 1909.

- Theodor Nöldeke: Sketches and preliminary work by J. Wellhausen. Issue 3: Remnants of Arabic paganism. Berlin 1887. Advertisement in: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG) 41 (1887), p. 707 ff.

- Rudi Paret : The Koran. Translation. Revised Paperback edition 2 vols. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1980. ISBN 3-17-005658-1 .

- Rudi Paret: The Koran. Commentary and Concordance . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1980. ISBN 3-17-005657-3 .

- William Robertson Smith : Lectures on the Religion of the Semites . The fundamental institutions. 3rd edition London 1927.

- Friedrich Stummer : Comments on Ibn al-Kalbī's book of idols . In: Journal of the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (ZDMG) 98 (1944), pp. 377–395.

- Julius Wellhausen : Remains of Arab paganism . Berlin 1897. (Reprint) de Gruyter, Berlin 1961 (online) .

- Frederick Victor Winnett: Safaitic Inscriptions from Jordan . University of Toronto Press 1957.

- Yaqut al-Hamawi: Geographical Dictionary . Ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. Leipzig 1866–1873.

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 9, p. 5 (sanam); Vol. 11, p. 176 (wathaniyya); Vol. 2, p. 546 (djinn); Vol. 10, p. 376 (tawaf).

- Karl Jettmar (ed.): The religions of mankind . 4.3: The pre-Islamic religions of Central Asia. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-011312-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ In general, see: Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum . Paris 1887ff

- ↑ See about him W. Atallah, article al-Kalbi , in: The Encyclopaedia of Islam , Vol. 4, Leiden 1978, pp. 494-496.

- ↑ See the foreword to the 1st edition, pp. 35–36

- ↑ In the 2nd edition (Cairo 1924) the foreword and introduction to the no longer existing 1st edition from January 4, 1914 are printed

- ↑ On the book of Ibn al-Kalbi, including reviews of the edition, see: Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic literature. Brill, Leiden 1967 vol. 1. p. 270.

- ↑ See about him: The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 1, p. 425, No. 10; on him and other members of the al-Alusi family of scholars see: Carl Brockelmann : History of Arabic Literature. Supplementary Volume 2. pp. 785-789. Brill, Leipzig 1938.

- ↑ Henrik Samuel Nyberg: Comments on the Book of Idols . In: Le Monde Oriental. Year 1939. p. 366; Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, pp. 26–27 (Introduction)

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 26 (introduction)

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Leiden, Brill, Vol. 11, p. 176

- ^ Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic literature . Leiden, Brill 1967. Vol. IS 385-388; The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Leiden, Brill, Vol. 3, p. 895

- ^ W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad at Medina . Oxford 1972 (reprint), pp. 65-66

- ^ The History of al-Tabari . State University of New York Press

- ^ Carl Brockelmann: History of the Arabic literature . Supplementary Volume II. Pp. 37-38. Leiden 1938; The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 6, p. 193

- ↑ See Michael Lecker: Idol worship in pre-Islamic Medina (Yathrib) . In: Le Muséon. Revue d'Etudes Orientales. 106 (1993), pp. 331–346 (with the original text in the appendix)

- ↑ The Chronicles of the City of Mecca . In: The History and Description of the City of Mecca by al-Azraqi. Leipzig 1858; Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic Literature . Vol. IS 344. Brill, Leiden 1967

- ↑ JW Fück: The ancestor of Azraqi . In: Studi Orientalistici in onore di G. Levi Della Vida . Rome 1956. Vol. 1, pp. 336-40; The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 1, p. 826 (al-Azraqī)

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 1, p. 453 (ʿAmr b.Luḥayy)

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 33

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 1, p. 997

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 3, p. 393; Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 97, note 140

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. P. 212; Robertson Smith: Lectures. 151

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 39; see below

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 98.

- ↑ Werner Schmucker: Investigations into some important land law consequences of the Islamic conquest movement . Bonn Oriental Studies. New series. Edited by Otto Spies. Bonn 1972. Volume 24, p. 51 and p. 67, note 2 d; The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 3, p. 393 (Ḥimā)

- ^ Walter Dostal (ed.), Andre Gingrich et alii: Tribal societies of the southwestern regions of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: social anthropological studies. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-7001-3598-X .

- ↑ See H. Lammen, pp. 100 ff.

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 47 and note 237; 306 and 371

- ^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, pp. 51–52; The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 8, p. 154 (nuṣub)

- ^ W. Robertson Smith: Lectures. Pp. 200-201

- ↑ a b Uri Rubin: The Kaʿba. Aspects of its ritual functions and position in pre-Islamic and early Islamic times. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), Vol. 8 (1986), pp. 119-120

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 8, p. 154

- ↑ M. Lecker: Idol worship in pre-Islamic Medina (Yathrib) , pp. 342–343

- ↑ Patricia Corne: Meccan trade and the rise of Islam . Princeton 1987, p. 107

- ^ William Robertson Smith: Lectures on the Religion of the Semites. The fundamental institutions. 3rd ed. London 1927, p. 185

- ^ William Robertson Smith (1927), p. 185

- ↑ J. Pedersen: The oath among the Semites . Strasbourg 1914, pp. 143-144

- ↑ M. Muranyi : “man ḥalafa ʿalā minbarī āṯiman…” addenda. In: Die Welt des Orients (WdO), Vol. 20/21 (1989/1990), pp. 116–119

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 4, p. 317; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism , p. 73ff.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. P. 110.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 10, p. 376; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism , p. 55

- ↑ See also the English translation by A. Guillaume: The Life of Muhammad. 3. Edition. Oxford University Press 1970, p. 619

- ↑ See: Carl Brockelmann: History of Arabic literature . Supplement volume 2, p. 536, Brill, Leiden 1938.

- ↑ See the note in: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 10, p. 376

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 9, p. 5

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, 48 and note 248

- ↑ Joseph Henninger: Geisterglaube. Pp. 304-305; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. Pp. 211-214.

- ^ Joseph Henninger, Geisterglaube , 308; Julius Wellhausen, Remains of Arab Paganism , 157–159

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition.Bd. 8, p. 399. 3) The meaning of Raḥman

- ↑ GE von Grunebaum: Islam in the Middle Ages . Artemis publishing house. Zurich and Stuttgart 1963. p. 151 and p. 492, note 31

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition.Bd. 8, p. 350

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition.Bd. 8, p. 760

- ↑ FV Winnett, p. 115. No. 841 and several times: the formulation is often used epigraphic topoi .

- ↑ Susanne Krone (1992), p. 465; see Franz Rosenthal in: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 20 (1996), pp. 260-262

-

^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, pp. 37–38.

The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi. On al-Lāt see: The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. 5 p. 692; J. Wellhausen: Remnants of Arab paganism. P. 32; W. Robertson Smith: Lectures. P. 201. Note 1 - ^ G. Hawting: The Literary Context of the Traditional Accounts of Pre-Islamic Idolatry. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), 21 (1997), p. 30; S. Krone (1992), p. 45

- ↑ See: MJ Kister: Some reports concerning al-Ṭāʾif . In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. Vol. 1 (1979) pp. 1ff. esp. 8-11; 18th

- ↑ See also: AJ Wensinck and JH Kramers: Short dictionary of Islam. P. 363. Brill, Leiden 1941. Susanne Krone: The Arab deity al-Lāt . Heidelberg Oriental Studies 23. Peter Lang. 1992

- ↑ Franz Rosenthal: The aramaistische research since Theodor Nöldeke publications. Brill, Leiden 1939, p. 86

- ↑ Michael Lecker: The Banū Sulaim. A Contribution to the Study of Early Islam. The Max Schloessinger Memorial Series. Monographs IV. Jerusalem 1989. pp. 37-42

-

^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, pp. 38–40.

The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi. On al-ʿUzzā see: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 10, p. 967; Wellhausen: Remnants of Arab paganism. P. 39; 44-45 -

^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 36.

The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi. On Manat see: The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. 6 p. 373 - ^ Corpus inscriptionum semiticarum . Vol. II. No. 198.

- ^ AJ Wensinck and JH Kramers (eds.): Short dictionary of Islam . Brill, Leiden 1941. p. 175

- ^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 43

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 44. - On Hubal see: The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. 3, p. 536; T. Fahd: Une pratique cléromantique à la Ka'ba préislamique. In: Semitica. 8 (1958), pp. 58 ff. And 73-76; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. P. 67; 75; 221; AJ Wensinck and JH Kramers (eds.): Concise dictionary of Islam . Brill, Leiden 1941. p. 175

- ^ Remains of Arab paganism , p. 175

-

^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 34.

The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi. - ↑ Al-Azraqi: Akhbar Makka . (Mekka 1352 H.), Vol. 1. P. 67. About these idols see: T. Fahd: Le Panthéon de l'Arabie centrale à la veille de l'hégire. Paris 1968, pp. 103-107; T. Fahd: Art. Isāf wa-Nāʾila , in: The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. 4 (1997), p. 91 f.

- ^ Uri Rubin: The Kaʿba . In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), 8 (1986), p. 106; Bärbel Köhler: The women in al-Wāqidī's Kitāb al-Maġāzī . In: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG), 147 (1997), p. 332.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. P. 77; M. Gaudefroy-Demombynes: Le pèlerinage à la Mekke. Étude d'histoire religieuse. Paris 1923, pp. 225-234.

- ^ Theodor Nöldeke : History of the Koran . Leipzig 1909. Bd. IS 177–178 with its reference to the Hadith literature

- ↑ al-Bukhari: Sahih, K. al-Ḥaǧǧ, 79; K. al-'Umra 10; in Ibn Hajar al-ʿAsqalānī : Fath al-bari , vol. 3. pp. 498–502; P. 614–615 (with commentary)

- ↑ Uri Rubin: The Ka'ba: aspects of its ritual functions and position in Pre-Isamic and early Islamic times. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 8: 124-127 (1986)

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 9, p. 817; Michael Lecker: The Banū Sulaym. A Contribution to the Study of Early Islam. Jerusalem 1989. pp. 99-100 note 4

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 6 p. 349.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Vol. 7 p. 825; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. Pp. 81-82

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 7, p. 824.

-

↑ Rosa Klinke Rosenberger, pp. 50–51; Julius Wellhausen, op. Cit. 57-58.

The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi. - ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Reste Arabischen Heidentums , pp. 59-60; The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi.

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, pp. 61–62; 138-139; The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi.

- ↑ FV Winnett, p. 99; No. 715

- ↑ Nöldeke (1887), p. 712

- ^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 50.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. P. 3; The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 2, p. 246; Werner Caskel: The old Semitic deities in Arabia . In: S. Moscati (ed.): Le antiche divinità semitiche. Rome 1958, pp. 95-117.

- ^ FV Winnett, p. 52; No. 300.

- ↑ Nöldeke (1887), p. 711.

-

^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 48.

The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi. - ^ Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic literature. Brill, Leiden 1975, Vol. II. Pp. 122-126; The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 3, p. 1176 (Imru'al-Qais)

- ^ Translation: Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 55.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism . Berlin 1897. pp. 45-48; The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 2, p. 241

- ↑ Vol. 1, pp. 262-263; Mecca 1352 H.

- ↑ Rosa Klinke Rosenberger, p. 50; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. P. 65

- ↑ The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi

- ↑ a b Sura 71 ( Nuh (Sura) )

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 60

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, pp. 34–36

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 82 after Wellhausen and Nöldeke

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 83; see also Wellhausen: Remains of Arab Paganism , p. 14

- ↑ In: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländische Gesellschaft (ZDMG) 41 (1887), p. 708. He translates the line as follows: “Greetings, Wadd, because we are no longer allowed to flirt with women because we are serious about religion has become."

- ↑ L. Baethgen: Contributions to the Semitic religious history . P. 101 (Berlin 1888)

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab paganism. P. 66

- ^ Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic literature . Vol. II. (Poetry), pp. 223-225. Brill, Leiden 1975

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 51: there the first line is incorrectly translated: You tell the person you meet that you put them to flight ...

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 53; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab Paganism, pp. 23–24 reads' Ammianas

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 4, p. 269; Ignaz Goldziher: Magic elements in Islamic prayer . In: Oriental studies dedicated to Th. Nöldeke . Giessen 1906, Vol. 1, pp. 308-312

- ↑ The Geographical Dictionary, Vol. 1. snal-uqaiṣir; The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 10, p. 788

-

↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 50.

The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi.

See also Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab Paganism , p. 63; The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition.Bd. 10, p. 788 - ↑ J. Pedersen: The oath among the Semites . Strasbourg 1914.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab Paganism, p. 61

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 1, p. 482.

- ↑ The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi: Michael Lecker: The Banū Sulaym. A Contribution to the Study of Early Islam. Jerusalem 1989. pp. 52-55

- ↑ The Book of Idols (Kitab Al-Asnam) by Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi.

- ↑ Julius Wellhausen: Remnants of Arab Paganism, pp. 19-20

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 57; see also ibid. Introduction , p. 20.

- ↑ A. Fischer: The idol Jaġūṯ. In: Journal of the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (ZDMG), 58 (1904), p. 877

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 35 and p. 82–83; Julius Wellhausen, op. Cit. Pp. 19-20

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 59; Julius Wellhausen: Remains of Arab Paganism, pp. 13–24

- ↑ See the comments on the idols mentioned in Surah Noah: Rudi Paret: Der Koran. Commentary and Concordance . P. 489–490 and Otto Eißfeldt: Names of gods and conception of god among the Semites. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG) 83 (1929), p. 27

- ↑ See: Theodor Nöldeke: History of the Qorāns. P. 124

- ↑ Rosa Klinke-Rosenberger, p. 61.

- ^ Theodor Nöldeke: History of the Qorāns. 1, pp. 137-138

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 8, p. 350 (rabb)

- ↑ MJ Kister: Labbayka Allāhumma, Labbayka… On a monotheistic aspect of a Jāhiliyya practice. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI). Vol. 2, pp. 44-45 (1980)