Battle of Uhud

| date | 625 |

|---|---|

| place | Mount Uhud near Medina in what is now Saudi Arabia |

| output | Victory of the attackers for the Quraish; however, the Islamic community cannot be crushed |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Quraish and their allies |

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| about 700 men | about 3,000 men |

| losses | |

|

about 65–70 dead |

about 20 fallen |

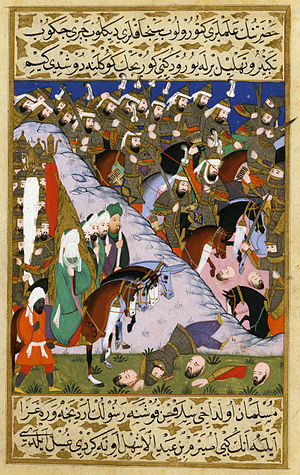

The Battle of Uhud ( Arabic غَزوة أُحُد, DMG ġazwat uḥud ) was the attack of the Quraish with the support of other tribes on Medina in the year 625. The battle was fought near Uhuds, a mountain near the oasis. It is seen in Islam as the day of visitation, misfortune and trial, with which Allah tested the Muslims and tempted the hypocrites. Around 65 to 70 Muslims and just over 20 attackers died.

Reports of the Battle of Uhud are only found in Islamic historiography , especially in Maghazi and Sira literature.

prehistory

A year earlier, the Battle of Uhud was preceded by the Battle of Badr , which came about in the course of an attempted caravan raid by the Muslims on a Meccan caravan. However, the Quraish learned of the plans of the Muslims and brought their caravan to safety and in turn sent a Meccan armed force led by Abu Jahl to fight the Muslim armed force. Despite numerical inferiority and inadequate equipment, the Muslims won the battle, in which several Meccans of high political and social positions, including Abu Jahl himself, were killed.

As a result, some Quraish - especially those who had lost family members at Badr - sought vengeance and demanded retaliation. So it happened that in the following year, under the leadership of Abu Sufyan, an attack was to take place on Medina in order to finally smash the Islamic community. For this purpose, all available men of the Quraish as well as neighboring, friendly-minded tribes were available to him.

Preparations in Medina

In Medina, the Muslims discussed whether to approach the enemy or whether one should prefer to remain in the oasis and defend oneself from there. While some older Muslims, including Mohammed himself, were in favor of the latter idea, others, mostly younger Muslims, insisted on the former. Eventually, Muhammad decided to go against the enemy, even though some of those who originally agreed to fight in Medina if the Prophet so chose. The latter, in turn, did not change his mind: "'It is not fitting for a prophet,' he replied, 'once he has put on his armor, take it off again before he has fought.'"

Meanwhile, the attacking Meccans and their allies had camped north of Medina. On the way of the Muslims to them, Abdullah ibn Ubayy and his followers returned to Medina. The reasons for this are unknown. Watt assumes that this might have had to do with the Prophet's decision to go against the enemy instead of remaining in Medina. " Whatever the precise thought in his mind, it must have been based on a selfish calculation of some sort. "

This is also mentioned in the Koran:

“And what happened to you on the day when the two multitudes met, it happened with the permission of God, and that He might know the believers and also those who hypocrites. And it was said to them, "Come here, fight in the way of God or ward off the enemy." They said, "If we knew there was going to be a fight, we would surely follow you." On that day they were closer to unbelief than to belief, they said with their mouths what was not from their hearts. And God knows better what they're hiding. These are those who, while they themselves remained behind, said of their brothers: "Had they obeyed us, they would not have been killed." Say: Keep yourselves from death if you tell the truth. "

The above verses may have been the first to distinguish between believers and hypocrites - those who only seemingly converted to Islam, but who were still in opposition to the Prophet.

The battle

The Muslims posted themselves at the Uhud Gorge. The 50 archers among the now 700 Muslims were ordered to keep the Quraysh cavalry away. On the side of the Quraish, as Ibn Ishaq reports, there were 3,000 men with 200 horses. The battle broke out and the women of the Quraish cheered their men on with tambourines. Among them was Hind al Hunud , the wife of Abu Sufyan and priestess of the Meccan goddess of victory. At first the luck in the battle was on the side of the Muslims, which Ibn Ishaq attributed to the help of Allah. The Muslims cut off the Quraish from their camp and their wives and servants fled. The standard bearers were killed. But when the Muslim archers left their post and turned to the Quraish camp because they thought the battle had been won and they wanted to plunder, Chālid ibn al-Walid saw his chance. The riders of the Quraish now had free access to the rear Muslim ranks. The flag was recaptured.

After the Muslims were stripped of their cover, their enemies inflicted great losses on them. Even Mohammed was hit. A stone knocked out one of his front teeth, dented his helmet, injured his face and lip and knocked him over.

As Muhammad's enemies approached more and more dangerous, he shouted “Who sacrifices himself for us?” And was heard by 5 of his fighters, who fought for him and died for him. A group of returning Muslims eventually saved him. They carried him to the Uhud Gorge, but there too they were attacked by the Quraishites. Mohammed realized that the Muslims had to stand higher on the mountain than the attackers in order to be able to defend themselves against them.

Ibn Ishaq did not narrate why the Quraish did not pursue Mohammed any further. They arranged to meet Mohammed in Badr next year and moved back to Mecca without attacking the poorly protected Medina.

Several verses of the Koran show what a severe defeat the battle of Uhud was viewed by the followers of Muhammad.

So it says in sura 3, verse 139f .:

“And do not wilt or become sad when you will have the upper hand if you are a believer. If you have suffered wounds, the (hostile) people have suffered similar wounds. We allot such days to men in turn. (...) "

Verse 153 of the same sura is - along with some other verses - related to the battle:

“When you ran away without turning to look at anyone while the messenger called to you far behind. Then He rewarded you with sorrow for (the sorrow inflicted on the prophet), lest you be sad about what had escaped you, nor about what had struck you. And God is aware of what you do. "

Threat of Hamza's death

During the fight, Hamza , Muhammad's uncle, was pierced by a spear and then killed. According to ancient Arabic tradition , the dead had their noses and ears cut off and processed into trophies. It is said that Hind al Hunud, the Quraysh priestess of victory, bit into Hamza's liver and gutted him. According to a report by the biographer of the prophets ibn Ishāq , Mohammed is said to have said the following when he saw Hamza's mutilated corpse:

"... Verily, if one day God gives me victory over the Quraish, I will mutilate thirty of their men!"

And further the report of ibn Ishaq says:

“And the Muslims, when they saw the Prophet's grief and anger at his uncle's murderers, swore: 'By God, if one day God lets us win over them, we will mutilate them like no Arab has ever mutilated anyone. '“

With regard to these threats by the Prophet and his companions, sura 16 , verse 126 is said to have been revealed:

“And if you impose a penalty (for an offense that has been committed against you), then do so according to what has been done to you (by the other side)! But if you are patient (and refrain from punishment), that's better for you (w. For those who are patient). "

"The prophet forgave them, was patient and forbade mutilation."

According to a report by at-Tabarīs , Abū Bakr , first caliph and thus the political successor of Mohammed, is said to have forbidden his troops from mutilating corpses, among other things. Islamic law forbids - on the basis of the Sunnah of the Prophet as well as these words of Abu Bakr and similar statements made by the caliphs of him - the mutilation of the corpses of killed enemies. In the legal understanding of Islamic states, this regulation has retained its validity up to the present day.

literature

- Frants Buhl : The life of Muhammad. 3rd, unchanged edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1961, pp. 252-260.

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam . Volume 10: Tāʾ - al-ʿUzzā. New Edition. Brill, Leiden et al. 2000, ISBN 90-04-11813-6 , p. 782, ( Uhud ).

- Marshall GS Hodgson : The Venture of Islam. Conscience and History in a World Civilization. Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam. Paperback edition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL et al. 1977, ISBN 0-226-34683-8 , p. 190 .

- Theodor Nöldeke : History of the Qorāns. Volume 1: On the Origin of the Qorān. 2nd edition edited by Friedrich Schwally . Dieterich, Leipzig 1909, pp. 192–194 .

- Francis E. Peters : The Monotheists. Volume 1: The peoples of God. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2003, ISBN 0-691-11460-9 , p. 104 .

- W. Montgomery Watt : Bell's Introduction to the Qurʾān (= Islamic Surveys. 8). Completely revised and enlarged. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1970, ISBN 0-85224-171-2 , p. 100.

- W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad at Medina. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1956, pp. 21-29 .

- W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad. In: Peter M. Holt, Ann KS Lambton, Bernard Lewis (Eds.): The Cambridge History of Islam. Volume 1, A: The Central Islamic Lands from pre-Islamic Times to the First World War. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1977, ISBN 0-521-29135-6 , pp. 47 f.

Footnotes

- ^ W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad. Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press, London et al. 1961, p. 140.

- ^ Francis E. Peters: Islam. A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 2003, ISBN 0-691-11553-2 , p. 76.

- ↑ a b The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume 10. New Edition. 2000, p. 782.

- ^ W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad at Medina. 1956, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Quoted from: Ibn Isḥāq: The Life of the Prophet. Translated from Arabic and edited by Gernot Rotter . Spohr, Kandern 2004, ISBN 3-927606-40-5 , p. 146.

- ^ W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad. Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press, London et al. 1961, p. 137.

- ^ W. Montgomery Watt: Muhammad. Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press, London et al. 1961, p. 138.

- ^ A b Antonius Lux: Famous women in world history. A thousand biographies in words and pictures. Lux, Murnau et al. 1963, p. 228.

- ^ W. Montgomery Watt: Bell's Introduction to the Qurʾān. Completely revised and enlarged. 1970, p. 100; see also: Theodor Nöldeke: History of the Qorāns. Volume 1. 2nd edition. 1909, p. 192 ff.

- ^ Theodor Nöldeke: History of the Qorāns. Volume 1. 2nd edition. 1909, p. 193 .

- ↑ Khoury's note: 'The grief that Muslims have endured should divert them from the war, with all that entails prey or suffering, and direct their attention to their shameful attitude towards the Prophet.' See The Koran . Translation by Adel Theodor Khoury. With the participation of Muhammad Salim Abdullah. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1992. p. 52

- ↑ Ibn Isḥāq: The Life of the Prophet. Translated from Arabic and edited by Gernot Rotter. Spohr, Kandern 2004, ISBN 3-927606-40-5 , p. 154 f.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. the Koran commentaries by al-Wahidi [1] and ad-Jalalain [2] as well as The History of al-Ṭabarī , Vol. 7. Translation of the annals at-Tabarīs by MV Mcdonald and W. Montgomery Watt. Suny Press, 1987. pp. 133 f.

- ^ Bernard Lewis: The Political Language of Islam. Paperback edition, 4th University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL et al. 1991, ISBN 0-226-47692-8 , p. 75 .

- ↑ James Turner Johnson: The Holy War Idea in Western and Islamic Traditions. 3rd printing. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park PA 2002, ISBN 0-271-01633-7 , p. 71 . For a corresponding tradition see: Muhammad Hamidullah : Muslim Conduct of State. Islamic Book Trust, Kuala Lumpur 2012, ISBN 978-967-5-06288-9 , p. 10 .

- ↑ Majid Khadduri : War and Peace in the Law of Islam. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore MD 1955, p. 102.

- ↑ See Muhammad Hamidullah: Muslim Conduct of State. Islamic Book Trust, Kuala Lumpur 2012, ISBN 978-967-5-06288-9 , p. 219 and sources cited there.

- ↑ See, for example, Article 3 of the Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam (PDF; 49 kB)