Islam in Europe

This article deals with the history and current situation of Islam in Europe . The Christian western European and Islamic countries share a common history of over thirteen centuries. For many centuries, regions that belonged to the European continent were under Islamic rule. These include, for example, Sicily or large parts of today's Portugal and Spain, the Arabic al-Andalus . Istanbul , the capital of the Ottoman Empire , is located on two continents, Europe and Asia. Rumelia , the European part of the Ottoman Empire, was under Ottoman rule until the end of the 19th century.

The common history is shaped by armed conflicts, but also by intensive trade, diplomatic and cultural exchange. In the course of this, mutual knowledge about the "other" culture grew. Connections to one's own identity and world of experience were established and found expression in memory-creating rituals, whereby in today's research the resulting “image of the other” often turns out to be a stereotype and appears to be constructed with regard to one's own cultural identity.

With the immigration of Muslims to Europe since the 1950s, large Muslim minorities have emerged in many European countries, so that the question of a common identity as the basis for successful integration arises again.

history

In the course of the history of Europe and the Islamic world, there were various, sometimes violent, sometimes peaceful contacts, which shaped the ideas of each other in different ways in the two regions. Times of relatively peaceful coexistence, for which the court of Staufer Emperor Friedrich II. Or the centuries-long coexistence of Christians, Jews and Muslims in Muslim-ruled al-Andalus are symbolic , alternated with epochs of armed conflict that are impressed on the “collective memory” of Western Europe and thus again assumed symbolic character, including the conquest of Constantinople (1453) and the subsequent rededication of Hagia Sophia - the coronation church of the Byzantine emperors - into a mosque or the victories in the naval battle of Lepanto and the battle of Kahlenberg .

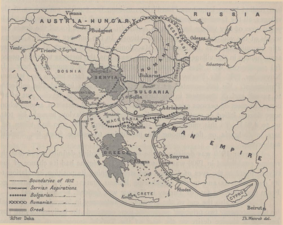

- Maps on the history of Islam in Europe

Islamic expansion until the end of the Umayyad dynasty

Early Middle Ages

The Hejra in September 622 marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar . Just a few decades later, Islamic-Arab armies won decisive victories over the Byzantine Empire and the Persian Sassanids . The appropriation and reshaping of the cultures of the conquered territories, including the ancient culture , which was already Christian at that time , led to an early heyday of Islamic culture , which in the following period again radiated into Christian Europe. The works of Islamic scientists - whose names were often appropriated in Latinized form in Europe - remained standard works of European science into the 16th century.

al-Andalus

On April 30, 711 an army of Arabs and North African Berbers landed in Gibraltar under the general of the Umayyad caliph Al-Walid I , Tariq ibn Ziyad . In the battle of the Río Guadalete Ibn Ziyad defeated a Visigoth army under King Roderich . Most of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered in a seven-year campaign. But in 718 the Visigoth Pelayo gained independence in northern Spain and established the Christian kingdom of Asturias . In the following years Muslim troops crossed the Pyrenees , occupied parts of southern France and carried out raids there ( Arabic غزوة ghazwa 'campaign, raid, attack battle'). In 732 they were defeated by the Franks under Charles Martell in the Battle of Tours , but were able to establish their rule permanently over most of the Iberian Peninsula.

In 755 the Umayyad Prince Abd ar-Rahman ibn Mu'awiya landed with Berber troops in Almuñécar in Andalusia. He was on the run from the Abbasids , who had overthrown their previous Umayyad dynasty in 750. In May 756 he overthrew the Abbasid governor of Al-Andalus Yusuf al-Fihri in Cordoba . With his elevation to the emir (756–788) the political organization of the Western Umayyad Empire began in Spain. Abd ar-Rahman founded the margravates of Saragossa , Toledo and Mérida to secure the border against the Christian empires in northern Spain. The Iberian Peninsula became part of the Western Umayyad Empire under the name of al-Andalus. From northern Spain, the territory of the Christian kingdoms expanded again in the course of the Reconquista during the following centuries.

Al-Andalus remained under Muslim rule until 1492, initially as a province of the Umayyad Caliphate (711–750), from 756 to 929 as the emirate of Córdoba , and from 929 to 1031 as the caliphate of Córdoba . After 1031 the area was ruled by a group of Taifa or "successor" kingdoms, then by the Maghreb dynasties of the Almoravids and Almohads ; eventually it fell again into Taifa kingdoms. For long periods, particularly during the time of the Caliphate of Cordoba , al-Andalus was a center of learning. Cordoba became a leading cultural and economic center of both the Mediterranean and the Islamic world. According to Islamic law, non-Muslims who belonged to one of the scriptural religions were counted among the "wards" ( dhimma ). The reign of Abd ar-Rahman III. and his son al-Hakam II is characterized by a particularly strong religious tolerance for the time. The Jewish population in particular achieved prosperity through science, trade and commerce. Jewish merchants ( Radhanites ) mediated trade between Christian Europe and the Islamic world. During this time, southern Iberia was asylum for the oppressed Jews of other countries. One of the most important Jewish scholars of this “ Golden Age of Jewish Culture in al-Andalus ” was Moses Maimonides, who was born in Cordoba in 1135 or 1138 . On the other hand, 48 Christians were executed in Cordoba in the 9th century for religious offenses against Islam. As " martyrs of Cordoba " they occasionally found imitators. More recently, research has increasingly focused on the multicultural coexistence in al-Andalus.

Limits of Islamic Expansion in Europe

The battle of Tours and Poitiers entered the “collective memory” of Western Europe in October 732 as an epochal turning point and the end of Islamic expansion in Western Europe. However, this importance was not attributed to the battle until the late 18th century by Edward Gibbon in his work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1788). The battle was not mentioned in medieval chronicles of the 11th century, for example by Marianus Scottus and Frutolf von Michelsberg . In truth, the Arab defeat at Constantinople in 718 seems to have put a much more emphatic halt to Islamic expansion into Europe. For centuries, Byzantium had to defend itself against coordinated and organized attacks by Arab armies and fleets, which followed one another at short intervals. It was not until the defeat of the Byzantine Empire in the battles of Manzikert (1071) and Myriokephalon (1176) that the settlement of Asia Minor by the Turkic Oghuz people and the establishment of the Sultanate of the Rum Seljuks made possible .

While the Muslims had already started shortly after the Islamic expansion to translate Greek and Latin authors of late antiquity into the Arabic language and to develop them further with the help of their own ideas, Christian authors like Jerome were opposed to the "pagan" philosophy of Aristotle, for example. Only for a short time, during the Carolingian Renaissance , were philosophical works of Greco-Roman antiquity discussed in Europe by scholars such as Alcuin . Overall, philosophical and scientific thinking in Western Europe - in contrast to Islamic science of that time - made little progress.

European high Middle Ages

The expanding Islam was initially perceived in Europe only as a military threat. In the 9th century, Erchempert von Montecassino reported an insidious attack by Saracen mercenaries on the city of Bari . The Saracens, who were “naturally wiser and more adept at evil”, used their knowledge of the fortifications for a nightly raid during and after which the “sleeping Christians were murdered or sold into slavery”. According to Edward Said (2003), contact with Islam in Europe initially symbolized “terror, devastation, the demonic, hordes of hated barbarians” that could only be met with “fear and a kind of awe”.

Crusades

In 1095 the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos asked Pope Urban II for support in the reconquest of the territory of Asia Minor. On November 27, 1095, at the Synod of Clermont , the Pope called for a crusade to the "Holy Land". The Kingdom of Jerusalem, established following the First Crusade , and other smaller Crusader states played a role in the intricate politics of the Levant for the next 90 years . After the end of Fatimid rule in 1169, the Crusader states were increasingly exposed to pressure from Saladin , who was able to recapture much of the region by 1187. Soon economic motives and motives for inner-European politics emerged: The economic interests of the Republic of Venice led to the Byzantine capital Constantinople being conquered and plundered by crusaders in the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

According to today's understanding, the Crusades, which ultimately only directly affected a small part of the Islamic world, had a comparatively small effect on Islamic culture, but permanently shook the relationship between the Christian societies of Western Europe and the Islamic world. Conversely, for the first time in history they brought Europeans into closer contact with the highly developed Islamic culture .

"Renaissance" of the 12th century

In the late 11th century, the areas of the Taifa Kingdom of Toledo (1085) and Sicily , which had previously been ruled by Muslim Arabs, were conquered by Christian rulers . The Arab scholars who remained in the newly conquered regions, a population still largely speaking Arabic and Greek, and the new Christian rule offered better access and favorable starting conditions for the work of European scholars who wrote Latin. They got to know scientific and literary works of Arabic literature. Lively translation work began; the multilingualism of the population made work easier. In Sicily, which was long part of the Roman Empire, Greek works could be translated directly into Latin. The Spanish Toledo, which had been under Arab rule as part of al-Andalus since 711, offered ideal conditions for translations from Arabic. The works of Greek and Islamic scientists, doctors and philosophers , translated into Latin , had a decisive influence on the development of Western European culture. The translation school of Toledo was of particular importance . In the 12th century, the acquisition of knowledge from Islamic science made a decisive contribution to the so-called "high medieval renaissance".

In 1142, Petrus Venerabilis , Abbot of Cluny Robert von Ketton , commissioned the baptized Jewish scholar Petrus Alfonsi and the monk Hermann von Carinthia with the first Latin translation of the Koran, the Lex Mahumet pseudoprophetae . With his works Summa totius heresis Saracenorum (“Sum of the heresies of the Saracens”) and Liber contra sectam sive heresim Saracenorum (“Against the sect or heresy of the Saracens”) he pursued the goal of refuting Islam from its sources. According to Said (2003), the prophet Mohammed was identified with Christ in a false analogy and classified as a “pseudo prophet” and “deceiver”.

According to Said (2003), Dante Alighieri's (1265–1321) Divine Comedy shows a more differentiated classification of individual Muslim scholars in the European worldview : In Canto 28 of the Inferno , Mohammed is subject to perpetual punishment as a cleavage of faith in the ninth ditch, while Avicenna, Averroes and Saladin are subject to perpetual punishment only have to stay with pre-Christian philosophers in the first circle of hell because they did not know the Christian revelation. According to Said, the classification - disregarding historical connections - indicates that these people are classified from an orientalist point of view in a closed, schematic worldview. They are interested in their function “on the stage on which they are placed” and on which their image fluctuates between the familiar, the similar and the “oriental foreign”.

Reconquista

As early as the early 8th century, al-Andalus was in conflict with the Christian kingdoms in the north, which expanded their territory militarily as part of the Reconquista . On January 2, 1492, the last emir Muhammad XII handed over . the city of Granada to the " Catholic Kings ", with which the Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula came to an end.

Despite the religious freedom guaranteed at the surrender of Granada , the forced conversion of the Mudéjares by the Catholic Church and the expropriation of Muslim religious institutions began as early as 1502 . After an uprising in Granada around 1499 , the monarchy ordered the forced conversion of Muslims or their deportation . In the period that followed, although many Muslims, known as Moriscos , converted to Christianity, they continued to practice Islam in secret and were exposed to persecution by the Inquisition .

The Alhambra Edict of March 31, 1492 ordered the expulsion of the Jews from Castile and Aragón on July 31, 1492, provided they had not converted to Christianity by then . Afterwards, many Sephardic Jews emigrated from Spain, and after 1496/97 also from Portugal, and found refuge in the Ottoman Empire, where they were welcomed by a decree of Sultan Bayezids II .

Elements and rituals of collective memory

In Western Europe, the Ayyubid Sultan Saladin was never forgotten, and no Islamic ruler of the Middle Ages is better known in Europe. Troubadours spread songs of the "noble pagans" and "knightly opponents" of the kings Richard I, the Lionheart of England and Frederick I Barbarossa . In the Islamic world, on the other hand, Saladin's figure only returned to consciousness through his positive assessment in Europe. In particular, the politically motivated trip to the Orient by the German Emperor Wilhelm II in 1898, during which he also visited Saladin's grave in Damascus, aroused the interest of Muslims.

A number of festivals still commemorate the Reconquista today. Exhibition fights between Moors and Christians ( Moros y Cristianos ) , colorful parades in historical costumes and fireworks, including the figure of El Moro at the Gigantes y Cabezudos as rituals create memories.

"Moros y Cristianos": Entry of the Moors ( El Campello , 2006)

"Moros y Cristianos": Ranks of Christians ( Elda , 2006)

Renaissance: Western Europe and the Ottoman Empire

While Christian Western Europe had to grapple with the expansion supported by Arab peoples from the time of the Crusades until the 13th century, the Ottoman Empire entered world history as an Islamic great power from the middle of the 14th century . At the beginning of the more intense contacts, the main focus was on the military capabilities of the Muslims, while details of social and economic life remained largely unknown. This did not change until the 15th century when, with the Age of Discovery and the Western European Renaissance, on the one hand, the Western European public became more interested in foreign countries and, on the other hand, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire towards Central Europe reached its climax in this epoch.

The conquest of Constantinople (1453) historically marked the beginning of an era of mutual relations, which came to a provisional conclusion in 1606 with the peace of Zsitvatorok . This treaty between the Roman Emperor Rudolf II and Sultan Ahmed I ended the Long Turkish War between the Habsburg Empire and the Ottoman Empire in 1606 and finally incorporated it into the political structure of the major European powers. Both empires turned to other conflicts; Europe sank in the Thirty Years' War , the Ottomans devoted themselves to the fight against insurrections in the eastern regions of Asia Minor, the wars against Poland and the third war against the Persian Empire of the Safavids .

First contacts in the 14th century

From the early 14th century, the emerging Ottoman Empire intervened in the local conflicts of the fragmented Christian-Orthodox rule areas of the Balkans . In 1343 Pope Clement VI. with the bull "Insurgentibus contra fidem" called for the first time to crusade against the Turks. Following the high medieval idea of the crusade, individual war campaigns took place. A European alliance against the Turks did not come about because of the simultaneous war between England and France and the occidental schism . Ottoman victories in the Battle of Mariza in 1371, 1389 on the Blackbird Field (Kosovo), the conquest of Bulgaria by Sultan Bayezid I in the summer of 1393 brought Europe into the immediate vicinity of the Ottoman Empire. A crusade involving various European countries ended in 1396 with the crushing defeat of the Christian army at the Battle of Nicopolis .

European-imperial claim of the sultans

After the conquest of Constantinople (1453) Sultan Mehmed II took the title "Emperor of the Romans " (قیصر روم / Ḳayṣer-i Rūm ) and thus consciously placed himself in the tradition and succession of the Eastern Roman Empire . The official name of the city was not changed to Istanbul until 1930, until then the name Constantinople was retained with all European and lordly connotations. In Europe, the fall of Constantinople was seen as an apocalyptic turning point. It was only a matter of time before the Ottoman Empire began a new offensive in the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe to assert its claim to rule. Suleyman I had the following inscription placed over the main entrance of the Suleymaniye Mosque he had built :

"Conquerors of the countries of the East and the West with the help of the Almighty and his victorious army, rulers of the empires of the world."

The main goal of Süleyman's European expansion policy was the Holy Roman Empire . Only by conquering the Roman imperial crown was he able to stand up as the successor of the Roman Empire and ruler of the West. He therefore sought the support of the German Protestant princes to win the in the Schmalkaldic League against the religious policy of the Catholic Emperor Charles V had allied, and included an alliance with the French king François I . This wrote:

“I cannot deny my desire to see the Turks mighty and ready for war, not for his sake, because he is an infidel and we are Christians, but to weaken the emperor's power, to impose high expenses on him and against all other governments to strengthen such a powerful enemy. "

"The Turk" as an arch enemy

The battle of Nicopolis and the subsequent massacre of Christian prisoners were widely discussed in Europe. Christian chroniclers, including Jean Froissart and Philippe de Mézières , reported on the battle. Johannes Schiltberger was an eyewitness to the battle and after his return from thirty years as an Ottoman prisoner of war reported on the battle and his travels through the Islamic world. The European conception of the Ottomans remained little differentiated: Froissart describes Bayezid as a polytheist; the Ottomans are equated with the Saracens ; according to French sources, Persians, Arabs, Syrians, Tatars and Lithuanians supposedly served in the Ottoman army. In mediaeval reporting, all conceivable opponents were typically located in the enemy army if more detailed information was missing. Even the name of the sultan remained unclear, Murad I and his son Bayezid were merged into one person: Froissart calls the sultan "roy Barach dit L 'Amourath Bacquin". The information conveyed was mainly limited to the military capabilities of the Ottomans; their religion, customs, social or economic order remained largely unknown. The picture turned out to be ambivalent: on the one hand, the European historians emphasized the cruelty and paganism of the "others", on the other hand they emphasized their discipline, piety and diligence and contrasted them with the transgressions in the Christian camp.

The conflicts between 1453 and 1606 shaped the European perception of the “fundamentally different”. The great conflicts of the Reformation time within the Christian world fall during this time . Both Catholics and Protestants used the construct of the "Turk" as "archenemy of Christianity" for their social and political goals. At the same time, diplomatic relations, trade and artistic exchange intensified, and educational trips, especially by Europeans to Istanbul and Anatolia, became fashionable. Overall, in addition to the stereotypical enemy image, an ambivalent image of the Ottoman Empire emerged as a multi-ethnic unit with a differentiated social structure, especially in its peripheral areas. With the victory in the Battle of the Kahlenberg , which ended the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna in 1683 , the perception of an immediate threat from “the Turks” in Europe also ended.

In contrast to the first centuries of Islamic rule in south-western Europe, the second in the south-east had lasting consequences: the Albanians and Bosniaks remained predominantly Muslim even after the reconquest, and Turkish minorities remained in countries such as Greece and Bulgaria.

Trade, Diplomacy and Cross-Cultural Exchange

Since the 13th century at the latest, there have been intensive trade relations, especially between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire, which are documented in the preserved archives of Venice. Archive sources from the Ottoman Empire on relations with the West are only available from 1453 and have only been the subject of more intensive research since the end of the 20th century. Venice was the only place in early modern Europe where Europeans could meet Muslims, especially the Ottomans, in large numbers personally and do business. The sultans were particularly interested in the protection of their subjects as well as individual aspects of trade, such as the export restrictions on grain and cotton from Asia Minor. In military terms, the Ottoman Empire aimed to break the Venetian supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean, which began with the conquest of the Mediterranean bases of Venetian Albania , Koroni in the 15th century, Cyprus (1570–73), Crete (1645–69), and the Morea in 1715 and the two-time attack on Corfu also succeeded.

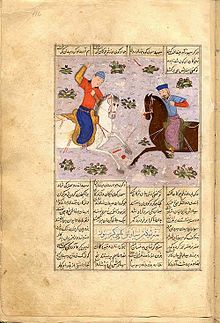

Sultan Mehmed II was the first Ottoman ruler to intensify cultural exchange with Europe. His interest in European culture began in his childhood: a notebook from his childhood is preserved in the archives of the Topkapı Palace Museum and contains drawings of portrait busts in the European style. His library contained European works on geography, medicine, history and philosophy, as well as European ones and Arabic maps and portolans . In the “Fatih Album”, a compilation of Florentine copperplate engravings, there is also a portrait of himself with the inscription “El Gran Turco”, the first portrait of the sultan in the European style. In 1461 Mehmed II asked Sigismondo Malatesta to give him the medalist Matteo de 'To send pasti; however, the trip was stopped by the Pope, who feared espionage. After the conclusion of peace with the Republic of Venice in 1479, artists traveled to Istanbul, among whom Gentile Bellini and Bartolomeo Bellano are known by name. Bellini painted, among other things, a portrait of Mehmed, which describes the Sultan in the inscription as "Victor Orbis", the conqueror of the world. Mehmed II's attempt to orientate himself on Italian art left its mark, temporarily also in the Ottoman miniature painting of his time. His court painter Sinan Bey and his pupil Şiblizâde Ahmed developed a new type of portrait art influenced by Italian painters. Mehmed's son Bayezid II called on European architects and engineers as advisors and commissioned a scroll that contained images of all seven Ottoman sultans up to himself. In doing so, he established a tradition of portraits of the Ottoman ruler that lasted until the end of the Ottoman Empire.

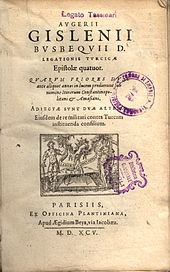

The almost simultaneous rule of Suleyman I (1494 / 6–1566) and Charles V (1500–1558) brought an intensification of diplomatic, cultural and trade relations between Western Europe and the Ottoman Empire. In addition to books and leaflets warning of the danger of the Turks , publications appeared that gave a more objective picture of the culture and society of the Ottoman Empire. Europeans traveled to the Ottoman Empire for various political and diplomatic purposes; They illustrated their books with representations made by painters who were traveling with them or who were commissioned on site. The woodcuts of Pieter Coecke van Aelst from Brussels and the costume books of Nicolas de Nicolay, who had accompanied a French embassy to Istanbul in 1551, became famous and often copied . The Danish painter Melchior Lorck accompanied the embassy of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq to Turkey from 1555–59 . Busbecq was sent from 1554–1562 by the Habsburg King and Emperor Ferdinand I to Anatolia for peace negotiations and reported about it in his "Turcicae epistolae" (Letters to the Turks) of 1595.

Since the time of Sultan Suleyman I , portraits of European rulers such as Charles V or Francis I appeared in Ottoman painting. At the time of Murad III. Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pascha commissioned an illuminated manuscript in the court script under the historian Seyyid Lokman and the chief miniaturist Nakkaş Osman , which was supposed to depict the history of the Ottoman sultans and to illustrate them with their portraits. For the production of this manuscript, completed in 1579, the Şemāʾil-nāme-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān ('Personal description book of the Ottoman ruling house'). the court scriptorium ordered series of sultans' portraits made in Europe in Venice, which are still kept in the Topkapı Palace Museum today.

In the intensified trade in luxury goods, both Western European and Ottoman manufacturers adjusted to the needs of the respective markets: In 1537/38 the first Koran with movable type was printed in Venice . Glassware was produced in Venice , in the 18th century in Bohemia and in the Netherlands , which stylistically can hardly be distinguished from the products of Islamic glass art . Ottoman manufactories produced carpets for the European market, and numerous illustrations of oriental carpets in Renaissance painting testify to their widespread use in Western Europe .

Between the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a political and commercial alliance existed between the English monarchy and the Saadi dynasty of Morocco . Trade agreements were made between Queen Elizabeth I of England and the Moroccan ruler Ahmad al-Mansur on the basis of their mutual hostility to King Philip II of Spain . The arms trade predominated in the exchange of goods, but there was also repeated direct military cooperation.

In addition, Elizabethan England sought the support of the Ottoman sultans in their efforts to disrupt the Portuguese and Spanish silver fleets . This became particularly clear in England's policy towards the Holy League and in the conspicuous silence of the English public in contrast to the rest of Western Europe after the naval battle of Lepanto. The correspondence of the Elizabethan with the Ottoman court chancellery has also come down to us, whereby the role of Elizabeth I as " Fidei defensor " was particularly emphasized in relation to Christian heresy. The positive attitude of English society towards Islamic countries is also reflected in the dramas of Elizabethan theater , for example in William Shakespeare's plays “ The Merchant of Venice ” and Othello . The Ottoman Empire's first trade capitulation with England, which had previously imported goods via Venice, dates from around 1580.

17th and 18th centuries

overview

In the Age of Enlightenment , knowledge of the Islamic world in Europe expanded and deepened: trade and diplomatic relations expanded. New collections of Arabic scripts in European libraries led to the emergence of Arabic linguistics. Translations from Arabic that met scientific standards made the works of Islamic authors generally accessible. Eyewitnesses such as the traveler Carsten Niebuhr , the Protestant theologian Christoph Wilhelm Lüdeke or the military advisor François de Tott provided new insights into the geography, society and political order of the Islamic countries they traveled to or in which they had lived. Lessing took the standpoint of tolerance in Nathan the Wise . In his tragedy Mahomet the Prophet Voltaire portrayed the founder of the religion as fanatical and intolerant. Goethe , who translated Voltaire's Mahomet in 1802 , published the series of poems West-Eastern Divan in 1819 .

Development of Arabic Philology in Europe

European scholars became increasingly interested in the Arabic language from the late 16th century . Learning and understanding was initially made difficult by the lack of suitable texts from which vocabulary and grammar could be researched. In the Netherlands, philologists such as Joseph Justus Scaliger and Jacobus Golius collected Arabic manuscripts which they later donated to the library of the University of Leiden . Scaliger had learned Arabic from Guillaume Postel . In 1613 the Arabic grammar of Thomas Erpenius appeared , in 1653 the Lexicon Arabico-Latinum by Golius. Around the middle of the 17th century, the prerequisites for a correct understanding of the Arabic language in Europe were in place; The works of Golius and Erpenius remained the European standard works well into the 19th century. To a lesser extent, European scholars were also interested in the other two languages of the educated Islamic world: Persian , the language of poetry and mysticism, and Ottoman Turkish , the language of administration and legislation.

- Islamic manuscript collections in European libraries

In the 16th century, large libraries , some of which were open to the public, emerged across Europe . Owning as extensive a book collection as possible, including works from distant countries, marked the Renaissance humanist and increased the social reputation of the owner even if they could not read the works. The trading companies that developed in the 17th century, such as the British East India and Levant Companies , the Dutch and French East India Companies, also brought books and manuscripts from distant countries to Europe among their goods.

In 1634, William Laud , the Archbishop of Canterbury, instructed the Levant Company that each of their ships should bring at least one Arabic or Persian manuscript on their way home. During his stay in Aleppo from 1630-1636 and 1637-1640 in Istanbul, Edward Pococke collected a large number of Arabic manuscripts, which Laud later transferred to the Bodleian Library . Pococke was the first holder of Laud's newly created Chair in Arabic Studies at the University of Oxford . When Antoine Galland stayed in Istanbul 1677–1678 and 1680–1685, he had precise instructions from the French finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert as to which books he had to look for and buy. The interest of the French court was directed primarily to early Christian traditions and works by ancient writers in Arabic, but Galland also acquired manuscripts of classical Islamic literature for his private library. In the Netherlands, Jacobus Golius and Levinus Warner compiled one of the largest collections of Islamic manuscripts of their time in Europe on behalf of the Leiden University Library . In 1612 Christian pirates captured the library of a Moroccan prince and handed it over to the Spanish King Philip II. The huge collection was cataloged and publicized by the Escorial librarian , Miguel Casiri , in the second half of the 18th century .

At the end of the 17th century, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the Leiden University Library, the Royal National Library in Paris, the Escorial Library and the Vatican Library owned the largest collections of Islamic manuscripts in Europe. There were also numerous private libraries.

- Koran translations into European languages

The Koran as an equivalent to the Christian Bible represents the fundamental document of the Christian debate with Islam. Robert von Ketton's 1143 translation of the Koran remained authoritative until the 18th century. It was first published in 1543 by Theodor Bibliander and printed by Johannes Oporinus in Basel. The printing project was supported by Martin Luther , who, in his analysis of Islam, saw the publication of the Koran text as the best means of counteracting the threat to the Christian faith through the teachings of Islam. An Italian translation appeared in Venice in 1547. This was translated into German by Salomon Schweigger in 1616 , and the German version was translated into Dutch in 1641.

In 1698 Ludovico Marracci published in Padua the first correct Latin translation of the Koran from the original text according to linguistic criteria. In two volumes, the Prodromus ad refutationem Alcorani (prelude to the refutation of the Koran) and the Refutatio Alcorani (refutation of the Koran), he juxtaposed the Arabic text with the Latin translation and added critical comments and a rejection of each individual sura. The Latin text was translated into German and French and - together with the English translation by George Sale (1734) - remained authoritative until the 19th century. Sales English Koran text was translated into German by Theodor Arnold in 1746 .

Attributed roles and identities

The geographical proximity of Western Europe to the Ottoman Empire had far-reaching consequences for the development of the respective identity in complex structured processes of attraction and repulsion. The population of a country or a cultural area often perceives itself as special and different by using “the other” as a mirror to determine what “we” are and are not. In their confrontation with Christian Western Europe, the Ottomans often emphasized their role as Muslims and religious fighters ( Ghāzī ) , which did not prevent them from adopting and using the achievements of non-Muslim cultures. Conversely, the Ottomans were vital to the development of a Western European identity. Occasionally, the Ottomans serve as a role model for qualities that Europeans would also like to have: Niccolò Machiavelli had already presented the discipline, incorruptibility and obedience of the Ottomans as models for his contemporaries in his Discorsi , followed by other philosophers such as Montesquieu , who in his Persian Letters uses the fictional correspondence of two Persians to formulate his socio-political ideas. In the United States House of Representatives , Suleyman I was honored with a relief among 23 people as one of the greatest legislators of all time.

In return, other European thinkers ascribed various negative character traits to the Ottomans in order to describe characteristics in the pairs of opposites cruelty - humanity, barbarism - civilization, unbelievers - true believers, lasciviousness - self-control, which they found desirable in their own society. The European debate about despotism in the 17th century would not have been possible without the image of the “despotic Turkish sultan”.

19th and 20th centuries

The political and economic dominance of Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries led to a self-interested policy of colonialism towards the countries of the Islamic world and their division into spheres of interest of the respective colonial powers. At this time, numerous reform movements developed in the Islamic countries, and their thinking is still of ideological and political importance today. In late 19th century Europe, the cultural trend of orientalism reduced the image of the Islamic world to the exotic and foreign.

Looking at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Eurocentric view of the societies of the Islamic world in modern political and intellectual culture is discussed very critically in the discussion about Orientalism . The debate about orientalism is also seen as a trigger for an increased scientific interest in one's own past in the Islamic world, especially in modern Turkey.

21st century

Numerous scientific publications in the 21st century deal with the common history of Europe and the Islamic world with the aim of recognizing historical enemy images and arriving at a new understanding of world history that emphasizes the common . The integrative concept of a Euro-Islam contrasts with public debates such as the headscarf and caricature dispute and public concern about the emergence of a parallel society shaped by Islam . The intensified persecution of Christians mainly in Islamic countries, the Islamist-motivated terrorist attacks and the refugee crisis shape the current discussion about the situation of Islam in Europe.

Sacred buildings as symbols of appropriation and integration

Both after the conquest of Constantinople and after the Reconquista, churches and mosques were demonstratively dedicated to the other religion. In the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, for example, after the conquest, the Christian mosaics, decorations and bells were removed or covered with plaster, the building was given minarets , which clearly identify it as a mosque from a distance. In a process of appropriation, further large mosques with central dome were built based on the model of Hagia Sophia .

In return, after the Reconquista, mosques were symbolically taken into Christian possession in Spain: A Gothic church was added to the existing indoor mosque of Córdoba from 1523. While Hagia Sophia was converted into a museum in 1923 by resolution of the Turkish Council of Ministers, the Bishop of Cordoba spoke out against converting the cathedral into an interfaith church in 2006. However, the status of Hagia Sophia as a museum in today's Turkey is also controversial.

The oldest - religiously used - mosques in Europe were built at the beginning of the 20th century. Central mosques in modern architectural design are increasingly emerging from the need for appealing and representative buildings . The increasing “visibility” of modern Islamic architecture is often still controversial at the moment. This is exemplified in the discussion about the DITIB central mosque in Cologne or the Swiss minaret dispute .

Great Mosque of Paris , 1923

DITIB Central Mosque Cologne , 2015

Regional developments

In Europe, the Iberian Peninsula , which lies directly opposite Islamic North Africa and West Asia, and the Balkan Peninsula have been under Islamic influence for the longest , which has been pushed back by centuries of reconquest . Spain had been Muslim for 200 years before z. B. the first German state emerged. Unlike on the Iberian Peninsula, however, Islam was not destroyed in the Balkans. The autochthonous Muslim minorities there have been part of European history for 700 years, as has Christianity.

Eastern Europe

In Eastern, Southeastern and Northeastern Europe, Islam is predominantly dominated by Turks and Tatars and traditionally faces predominantly Orthodox Christians or Slavic atheists as well as Catholic Poles. The North Caucasian city of Derbent (Dagestan) was the first city in Europe to become Islamic in the 7th century - in contrast, none of the Slavic peoples was Christianized at that time, and a first Russian state did not emerge until the 9th century. The first Muslims settled in Romania a few decades before the first Romanian principalities even emerged.

Balkan Peninsula

- See main articles: Islam in Albania , Islam in Bosnia , Islam in Bulgaria , Islam in Romania, and Greek Muslims

In the Balkans, Bosnia and Herzegovina was under the rule of the Ottomans for 420 years, Macedonia 540 years, Bulgaria for around 500 years and Albania for over 400 years , Serbia as well for 400 years, the Romanian Dobruja for 380 years and Greece for 370 years. But only Eastern Thrace (European Turkey) has remained Turkish to this day ( Edirne since 1361), Istanbul , conquered by the Turks in 1453, is now the second largest city in Europe after Moscow with over 10 million inhabitants. In Didymoticho in northern Greece is the Çelebi Sultan Mehmed Mosque from the 14th century, which is the oldest on European soil.

But Islamic rule did not automatically mean the Islamization of the population; only Albanians and Bosniaks converted to Islam in the majority. In Bulgaria, Romania , Greece and Macedonia there are still Islamic minorities of the Balkan Turks and Slavic Muslims in Bulgaria, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro (Sanjak) - in Macedonia the proportion of Muslims is 33%, in Cyprus after 1974 18 %, in Bulgaria 12–15%, in Romania 0.3%.

Russia and Ukraine

- See main articles: Islam in Russia and Islam in Ukraine

In Russia , the country with the largest Muslim population in Eastern Europe, and the Ukraine , Islam is primarily shaped by Tatars - in Russia for over 750 years by Volga Bulgarians and Volga Tatars , in Ukraine for over 750 years by Crimean Tatars .

If one follows the classic view that the Urals and the Caucasus form the borders between Europe and Asia, then the three largest mosques in Europe are in Russia: the Akhmat Kadyrov mosque in Grozny, the Kul Sharif mosque in Kazan and the mosque in Makhachkala . (Dem is the Strahlenberg definition contrary, the Grozny, Makhachkala and the entire North Caucasus is one of the Asian part of the country, as it south of the prestigious than limit Manych depression is.) Together with the Islamic settlement belt on the Volga, the Russian North Caucasus one of the most politically unstable Islamic regions Europe with over 100 ethnic groups. Due to the difficult social situation, attitudes hostile to the Caucasus and Islam have recently spread among the population of Russia, which has led to the disadvantage and discrimination of the Muslim minorities.

Western Europe

In Western, Southwestern and Southern Europe, Islam is traditionally shaped by North African Arabs and Berbers and contrasts with Catholic Christianity from Romanic nations.

Iberian Peninsula

While Portugal was Islamic for over 500 years, the Arab-Berber and Moroccan rule ( Umayyads , Almoravids , Almohads and Nasrids ) lasted almost 800 years in Granada, Spain. From the Arab conquest in 711 to the final expulsion of the Muslims by the Christian Inquisition in 1614 it was even more than 900 years.

In Spain, only Andalusia and Murcia in the south and Valencia and the Ebro Basin ( Saragossa ) in the east (Levant) were centers of Arab settlers, who at times made up up to 80 percent of the population. Even today, precisely those areas of Spain (but also Catalonia ) are the main settlement areas of Muslim immigrants and centers of Islam in Spain.

France

- See main article: Islam in France

Parts of France had already been conquered by Muslims in 719, before today's France came into being (987). The southern coast of France was under direct Arab rule for a short time, but for centuries it was threatened by raids and looting by the Arabs (also known as Saracens).

On the other hand, France was the only country in Europe that concluded a permanent alliance with the Turkish Muslims against its Christian neighbors.

Italy

- See main article: Islam in Italy

In Italy, the Muslims were called into the country by rival princes. Parts of Italy had already been conquered and Islamized by Muslims before the Papal State came into being in 753 (for example the island of Pantelleria in 700, parts of Sardinia since 720). In Sicily, which was under Arab rule from 827 to 1091, the Muslim population reached 50% in the Middle Ages, as in Spain, most Arabs and Berbers stayed on the island for another 150 years after the Christian conquest. Today's Muslims in Sicily are predominantly Tunisian and Moroccan immigrants from the second half of the 20th century.

The Italian mainland has a lot in common with France. Parts of southern Italy, especially Apulia , were (like parts of southern France) briefly under direct Arab rule, but for centuries Italy, including the north, was plagued by Arab raids and looting inland. In northern Italy, too, the Muslims were first called into the country by King Hugo I.

Today's Muslims in Italy, over a million, are mostly from Morocco, Albania and Tunisia. Egyptians, Bangladeshis and Senegalese are the next largest immigrant groups of Islamic faith.

Central and Northern Europe

While Islam in Germany and Catholic Austria is predominantly influenced by West Asian today, Protestant north-western Europe is opposed to a predominantly South Asian Islam of naturalized immigrants. The presence of Islam in Germany has been based increasingly on immigration from Turkey to the Federal Republic of Germany since around 1960 .

German-speaking Central Europe

- See main articles: Islam in Germany , as well as Islam in Austria and Islam in Switzerland

In Germany today there are around five percent Muslims. When it comes to births, the proportion of children with a Muslim background is already more than 10%. Most Muslims came to Germany and Austria as guest workers in the 20th century, especially in the 1970s and 1980s, the majority of whom were Turks and Turkish Kurds . The image of Islam in Germany is therefore dominated by Turkish people.

In contrast to Germany or France, most Muslims in Switzerland are refugees from the Bosnian war refugees of the 1990s (the second largest group are Turkish immigrants).

In Austria , too , Muslim Bosnians now make up the second largest group of Muslim immigrants after the dominant Turks . Austria had a different approach to Islam from the history of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Since the great conquests of the 1530s, the Ottomans formed a more important minority of the Habsburg monarchy, albeit primarily in the Hungarian part of the country. Islam became a state-recognized religion as early as 1912 , because from 1878 Bosnia-Hercegovina was under Austro-Hungarian rule for four decades, since then the first Bosniaks have also lived in what is now Austria. Within the Austro-Hungarian Army, the Bosniak troops were considered to be particularly loyal to the emperor, which is why imams were also active to look after Muslim soldiers. In addition to the free exercise of religion, Islamic religious instruction in schools, the right to pastoral care in public institutions such as hospitals, and the state training of imams in an Islamic-theological institute (University of Vienna, since 2016) are associated with the recognition. In recent years, the sole right to representation for all Muslims since 1979 by the official Islamic religious community , which is Sunni-dominated , has been increasingly questioned - by the Sunni-Turkish side as well as by Shiites and Alevis. The latter were recognized independently in 2013, but are also divided, especially with regard to membership in Islam; other Islamic communities are initially only registered denominations.

Eastern Central Europe and the Baltic States

- See main articles: Islam in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus , Islam in the Czech Republic and Slovakia , Islam in Finland

In contrast to the rest of Central and Northern Europe, there has been a small minority of Muslim but assimilated Tatars in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus, which was under Polish-Lithuanian rule until the Russian conquest , and thousands of Poles and fighters against the Russians for around 600 years Hungarians adopted Islam in exile in Turkey after the revolution in 1849. As early as the Middle Ages, the Saqaliba had made their way from Poland and Eastern Central Europe to Andalusia, Tunisia and Egypt and, like the Poles later, made careers in the Islamic state as Slavic Muslims.

With the partition of Poland, some Tatars fell under Prussian-German rule. A Muslim Tatar minority has been resident in Finland since the 19th century, but most Muslims in Finland, as in the rest of Scandinavia, are now Turkish or Arab (especially Moroccan and Iraqi) and Somali immigrants.

In Hungary , as early as the Middle Ages, Muslims came to the country as body guards of kings. Hungary, parts of Slovakia or Croatia and the Romanian Banat, however, were under Turkish rule for 150 years between the first battle (1526) and the second battle near Mohács (1687), like the Balkans.

North Sea coast

- See also: Islam in the Netherlands

Most British Muslims are immigrants from the former colonies or their descendants. At its peak, around 100 years ago, the British Empire had subjugated around a quarter of the earth's surface and made around a quarter of all Muslims worldwide its subjects. Around 1900 Great Britain ruled over 240 million Muslims worldwide, almost 60 million in British India alone , and even today almost 70% of the Muslims in Great Britain are Indians or Pakistani and Bengali . British Islam is therefore unlike z. B. France and Germany are more Indian than Arabic and Turkish.

Muslims in Europe today

Immigration since the 1950s

Since the 1950s, the number of Muslims in the states of Europe has increased due to immigration from Islamic countries. The target countries were initially countries in northern Western Europe, such as France, Great Britain, the Scandinavian, Benelux or German-speaking countries. More recently, Spain and Italy have also attracted Muslim immigrants. Most of the immigrants come from North Africa, Turkey or Pakistan, with different distribution in the target countries concerned. In many European countries, Muslims have become strong and influential minorities through immigration.

statistics

In 2005 there were between 42 and 53 million Muslims in Europe , around 6 to 7.5% of the continent's 700 million inhabitants. About a third (about 14-22 million ethnic Muslims ) were in Russia , about 16 million of them in the European Union and just under 10 million in the European part of Turkey . Albania , Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina are the only countries in Europe with a Muslim majority. There are also Muslim majorities in northern Cyprus, Sandžak (southwest Serbia ), some provinces of Bulgaria , Macedonia and Greece as well as in the Russian republics of Tatarstan , Bashkortostan , Dagestan , Chechnya , Ingushetia , Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia . Within the European Union, France with 5 to 6 million and Germany with over 4 million believers have the largest Muslim minorities . The EU average was 3.28% before EU enlargement in 2004 , then fell slightly and rose again to 3.23% in 2007 due to the inclusion of Bulgaria (around 12%). Above the EU average are France with 8.2%, the Netherlands with 4.9% (according to other information 5.7% Muslims in the Netherlands), Greece with 4.7%, Germany with 4.5% (other information according to more than 5%) and Belgium with 3.6% (according to other data 5% Muslims in Belgium), Austria with 3.0% is slightly below (according to other data 4.2% Muslims in Austria). Switzerland has a share of 5.8% Muslims in the total population.

Admission of countries with Muslim populations to the European Union

In 1987 Turkey and Morocco applied for membership in the European Union. While accession negotiations are now being conducted with Turkey after a long period of hesitation , Morocco's application for membership was rejected for geographical reasons (again in 1991/92 and 1997). Morocco and Tunisia have had association agreements with the EC since 1968, together with Libya, Algeria, Egypt, Syria , Lebanon , Israel and Palestine , the Arab Mediterranean countries are integrated into an agreement to form a Euro-Mediterranean free trade area through the " Barcelona Process " , Libya and Morocco are involved in the EU strategy to prevent immigration with reception and internment camps.

With Albania (59% Muslims) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (50.7% Muslims), two other states want to join the EU. Essentially, according to various representatives of the EU, there should be no problems in these two countries due to the dominance of Islam, so that this is not seen as an obstacle on the way to the EU. Albania was officially granted EU candidate status in 2014 , but accession negotiations have not yet taken place. Due to its political structure, Bosnia-Herzegovina is still a “potential candidate for membership”.

Integration research

After the Madrid train attacks in 2004, the violent reactions to the Mohammed cartoons in 2005 and the Islamist terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo in January 2015 and November 13, 2015 in Paris , as well as against the background of a growing list of terrorist attacks with an Islamist background in Europe, the Relations between Europe and its Muslim immigrants have been the subject of public discussions about successful integration . The crimes of a small number of Islamist terrorists compared to the total number of Muslim immigrants are in part attributed to “Islam” as a group which poses a threat to liberal democratic institutions and values. In contrast, academic integration research focuses on the views and life experiences of "ordinary" Muslims in European societies, and on the question of the extent to which cultural and religious factors influence social relationships with public institutions and the majority of the population.

Eurislam project

As part of the EurIslam project, more than 7,000 people over the age of 18 were interviewed in six European countries (Germany, France, UK, Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland). These were divided into five groups: members of the respective national majority population (“natives”) formed the comparison group, Muslim immigrants from four countries or regions were interviewed in parallel: Turkey, Morocco, Pakistan and the former Yugoslavia. A distinction was made between three generations of Muslim immigrants: those who were born in one of the four countries of origin considered and only arrived at their current place of residence after the age of 18 ("1st generation"), those who were born in the country of origin, but immigrated before the age of 18 ("1.5th generation"), and those who were already born in the country of immigration ("2nd generation"). All persons interviewed in the four Muslim groups had to be either Muslim themselves or at least one of their parents. Men and women were interviewed separately. The survey was carried out by means of structured interviews by bilingual interviewers. In contrast to previous longitudinal studies , the Eurislam study was designed as a cross-sectional study , i.e. it examined a given group at a specific point in time.

In 2015, Ruud Koopmans published an analysis based on EurIslam data on factors influencing the integration of Muslim immigrants into the European labor market. All four Muslim groups had a significantly higher unemployment rate than the comparison group. Immigrants from Turkey and Pakistan in particular were two to three times as likely to be unemployed as the “locals”. Muslim women were unemployed more than the average. Their employment rate only increases with higher educational qualifications and in the second generation. According to the data, lower educational qualifications can only partially explain these observations. Rather, the variables language skills, contacts with (including marriages with) locals and the role model of women were statistically significant in relation to successful integration into the labor market.

Earlier longitudinal studies had assumed possible discrimination by local employers ("ethnic disadvantage") as an explanation for the different successes of "local" and immigrants in the labor market. Accordingly, successful integration into the labor market would be the key to integration. However, the factor “experience of discrimination” did not prove to be statistically significant in the current study. On the contrary, Koopmans comes to the conclusion that cultural assimilation in terms of language skills, contacts with locals and women's understanding of roles promotes successful integration into the labor market. The most important role here is played by language skills. If these three variables are taken into account in the analysis, influencing factors such as the time of immigration also lose their importance.

Chronology (key dates)

- 642, barely ten years after Muhammad's death, Arabs conquer Derbent for Islam.

- In 652 first Arab attacks also on Byzantine Sicily and in 674 on Constantinople

- 711 Victory of the Arabs and Berbers in the Battle of Jerez , the Visigoth Empire (Spain) becomes Islamic, however

- 718 defeat at Constantinople , but from then on there was a Muslim community and mosque in the city (first Muslim community in the Balkans)

- 732 Defeat of the Arabs and Berbers in the Battle of Tours , further attacks on the Frankish Empire failed, as did the subjugation of the Khazars on the Volga in 737 , which (after Arab advances into the Astrakhan area) T. Become Muslim

- 827-1091 Sicily under Arab rule

- 846 sack of Rome by the Arabs

- 1064–1492 Christian Reconquista in Spain (Toledo recaptured in 1085, Zaragoza fell in 1118, Lisbon in 1147, Valencia in 1238 and Seville in 1248)

- 1096–1291 crusades (first crusade already 1064 against the Spanish Barbastro, further against the Ottoman Turks in 1396 and 1444)

- 1212 Christian victory over Moroccan Muslims in the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa and 1340 in the Battle of the Salado

- 1352 (Tsympe) and 1354 (Gallipoli) first Ottoman bridgeheads in the Balkans

- 1371 victory of the Turks in the battle of the Mariza and 1389 in the battle on the Amselfeld (Kosovo) over a coalition of Serbs with other Balkan peoples (last unified resistance of the Christian and Slavic Balkan peoples) and

- In 1396 in the battle of Nicopolis also via Franco-Hungarian crusaders

- 1444 defense of a last crusade in the battle of Varna and 1448 second battle on the Amselfeld

- 1453 siege and conquest of Constantinople, from 1471 Ottoman advances as far as Austria and Italy

- In 1492 Muslim Granada fell to Spanish Christians, Austrian defensive victory against Ottoman raids

- 1526 conquest of Hungary, but in 1529 unsuccessful attack by the Turks on Vienna (1536 Turkish-French alliance)

- 1552/56 Russia conquers Kazan and Astrakhan , Ottoman counterattack on Astrakhan 1569

- 1571 Victory of a Christian alliance over the Turks in the sea battle of Lepanto

- 1572 The battered Russia prevents a conquest by Crimean Tatars and Turks in the Battle of Molodi

- 1609/14 expulsion of the Muslims and Moriscos from Spain, but from then on raids by Moorish pirates as far as Iceland, Denmark and Ireland

- 1676 Turkish protectorate over southern Ukraine

- 1683 Defeat of the Turks before Vienna and collapse of their rule in Hungary and the Ukraine (1699)

- In 1739, with the departure of Austria from the Turkish Wars, the Peace of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), Western European support for the Greek War of Independence (1821–32) and the Russian-Turkish treaty of Hunkiar Skelessi (1833), the Russian pressure on the Turkish Empire to, despite Western European intervention in the Crimean War (1853–56) the Turks lost all Balkan provinces between 1877 and 1912

- From 1798 colonization of Islamic states: in 1798 France conquered Egypt, 1830 Algeria, 1881 Tunisia and from 1891 West Africa, in 1882 the British then occupied Egypt and 1898 Sudan, Germany acquired Sansibar in 1885 and allied with the Ottoman Empire in 1898, Italy conquered Libya from 1911 , France and Spain finally split Morocco up among themselves in 1912. After the Turkish defeat in the Balkan Wars of 1912/13, Muslim minorities in the Balkans fall under Christian rule, flight and expulsion, Albania becomes independent

- Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire are allies in the First World War (1914-18), 1915/16 defensive Turkish defensive victory in the Battle of Dardanelles , but defeat of the German-Austrian-Turkish alliance

- from 1920 Kemal Ataturk westernized the rest of Turkey, Syria and Lebanon fell to France, Palestine as well as Jordan and Iraq fell to Great Britain (Jerusalem 1917-47 British)

- 1923 In the Treaty of Lausanne it is agreed that 1.25 million Turkish citizens of the Greek Orthodox faith living in Turkey will be expelled to Europe (Greece).

- In 1956 the British-French-Israeli intervention in Egypt fails , symbolic end of European colonial dominance over the Orient; Morocco and Tunisia become independent in the same year, Algeria only after the Algerian War in 1962

- 1992-1995: u. a. In the Srebrenica massacre, up to 8,000 Muslim Bosniaks are murdered by the Bosnian Serb army.

- since 2004: in Europe there are repeated Islamist terrorist attacks , u. a. 2004 in Madrid , 2005 in London , 2015 in Paris and 2016 in Brussels , in Nice and in Berlin .

See also

- Emirate of Cordoba or Caliphate of Cordoba and Taifa kingdoms

- Islamic fundamentalism

- Islamism

- Islamophobia and Eurabia

- Yugoslav Wars

- Boy harvest and booty Turks

- List of Grand Viziers of the Ottoman Empire

- List of mosques in Germany and List of mosques in Europe

- Ottoman Empire or Turkish History

- Political and Social History of Islam

- Stari Most in Mostar

- Economic history of the Ottoman Empire - on the economic relations between Europe and the Ottoman Empire

literature

- Mohammed Arkoun: L'islam et les musulmans dans le monde. Paris 1993

- Alexander Bevilacqua: The republic of Arabic letters - Islam and the European enlightenment . Belknap Press (Harvard University Press), 2018, ISBN 978-0-674-97592-7 .

- Franco Cardini : Europe and Islam. Story of a misunderstanding . Munich. 2004. ISBN 3-406-51096-5

- Georg Cavallar : Islam, Enlightenment and Modernity. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-17-033933-0 .

- Georges Corm: Misunderstanding Orient. Islamic culture and Europe , Rotpunktverlag, Zurich, 2004, ISBN 3-85869-281-6

- Hichem Djait and Peter Heinegg: Europe and Islam . Berkeley 1985. ISBN 0-520-05040-1

- Patrick Franke: Islam: State and Religion in Modern Europe , in: European History Online , ed. from the Institute for European History (Mainz) , 2012 Accessed on: December 17, 2012.

- Michael Frassetto and David R. Blanks: Western Views of Islam in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Perception of Other ISBN 0-312-21891-5

- Jack Goody : Islam in Europe. Polity Press 2004. ISBN 975-269-110-2

- Shireen T. Hunter: Islam, Europe's Second Religion: The New Social, Cultural, and Political Landscape . ISBN 0-275-97608-4

- Peter HF Jakobs Alber: Turkey. Antiquity, Christianity, Islam. Knecht Verlag, 1999, ISBN 978-3-7820-0832-7

- Silvia Kaweh: Islam in Germany (historical outline) . In: Handbook of Religions. Churches and other religious communities in Germany , ed. by Michael Klöcker and Udo Tworuschka , (loose-leaf work since 1997, 2-3 additional deliveries annually), Chapter IV, 12th EL 2006.

- Günter Kettermann: Atlas on the history of Islam. Darmstadt 2001. ISBN 3-89678-194-4

- Daniel G. König: Islam and the genesis of Europe . Between ideology and history . Saarbrücken 2018.

- Abderrahim Lamchichi: Islam-Occident, Islam-Europe: Choc des civilizations ou coexistence des cultures .2002. ISBN 2-7384-8783-1

- AlSayyad Nezar: Muslim Europe or Euro-Islam: Politics, Culture, and Citizenship in the Age of Globalization . 2002. ISBN 0-7391-0338-5

- Robert J., Jr. Pauly: Islam in Europe: Integration or Marginalization? . ISBN 0-7546-4100-7

- Florian Remien: Muslims in Europe: Western State and Islamic Identity. Study on the approaches of Yusuf al-Qaradawi, Tariq Ramadan and Charles Taylor , Schenefeld / Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-936912-61-6

- Muslims in the rule of law. With contributions by Lord Nazir Ahmed, Janbernd Oebbecke, Muhammad Kalisch, Mohamed Mestiri, Murad Wilfried Hoffmann, Anas Schakfeh, Matthias König, Wolfgang Bock, Andreas Rieger , ed. v. Thorsten Gerald Schneiders u. a. Lit publishing house. Münster 2005. ISBN 3-8258-8024-9

Web links

- bpb From Politics and Contemporary History 1-2 / 2006: Parallel Societies? ( PDF file)

- Federal Agency for Civic Education: Muslims in Europe

- Federal Agency for Civic Education: Formation of Islam in Europe

- Center of the Modern Orient: Muslims in Europe

- ORF: Islam in Europe

- NZZ: Islam in Europe

- Collection of articles and documents on the subject of Islam in Europe

- Islam portal Qantara.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Robert Born, Michael Dziewulski, Guido Messling (ed.): The Sultan's world: The Ottoman Orient in Renaissance art . 1st edition. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2015, ISBN 978-3-7757-3966-5 .

- ↑ a b Almeida Assmann: The long shadow of the past. Culture of remembrance and politics of history. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-406-54962-5 , p. 59 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c Eckhard Leuschner, Thomas Wünsch (ed.): The image of the enemy. Construction of antagonisms and cultural transfer in the age of the Turkish wars . 1st edition. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-7861-2684-3 .

- ^ Gundula Grebner: The 'Liber Introductorius' of Michael Scotus and the reception of Aristotle: the court of Frederick II as a hub of cultural transfer. In: Mamoun Fansa, Karen Ermete (ed.): Kaiser Friedrich II. (1194–1250). Mediterranean world and culture. Oldenburg 2008, pp. 250-257.

- ^ André Clot : Moorish Spain: 800 years of high Islamic culture in Al Andalus. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96116-5 .

- ^ Walter Kaegi: Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. (PDF) 1992, accessed on May 15, 2016 .

- ^ Hugh Kennedy: The Great Arab Conquests . Da Capo Press, Philadelphia 2007, ISBN 978-0-306-81728-1 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Michael McCormick: Origins of the European Economy. Communications and Commerce AD 300-900 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2001, ISBN 978-0-521-66102-7 .

- ^ Ilan Stavans : The Scroll and the Cross: 1,000 Years of Jewish-Hispanic Literature . Routledge, London 2003, ISBN 978-0-415-92931-8 , pp. 10 .

- ↑ Joel Kraemer: Moses Maimonides: An Intellectual Portrait. In: Kenneth Seeskin (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-81974-9 , pp. 10–13 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Orthodox Europe: St Eulogius and the Blessing of Cordoba. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009 ; Retrieved June 9, 2016 .

- ^ Martina Müller-Wiener, Christiane Koche, Karl-Heini Golzio, Joachim Gerlachs (eds.): Al-Andalus and Europe. Between Orient and Occident. Foreword by the editors . Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2000, ISBN 3-935590-77-6 , p. 10-11 .

- ↑ Salma Khadra Jayyusi (ed.): The legacy of Muslim Spain. Handbook of Oriental Studies, Dept. 1. The Near and Middle East. 2 volumes . Brill, Leiden 1992, ISBN 90-04-09952-2 .

- ^ Ekkehart Rotter: Mohammed in Bamberg. The perception of the Muslim world in the German Empire of the 11th century. In: Achim Hubel, Bernd Schneidmüller (Ed.): Departure into the second millennium. Innovation and continuity in the middle of the Middle Ages. Ostfildern 2004, pp. 283-344, here: p. 306.

- ↑ Created by Montecassino: Historia Langabardorum Beneventanorum , chap. 16: "[...] sunt natura callidi et prudentiores aliis in malum [...] populumque insontem partim gladiis trucidarunt partim captivitati indiderunt" online , accessed May 25, 2017

- ^ Edward Said: Orientalism . Penguin Modern Classics, London, New York 2003, ISBN 978-0-14-118742-6 , pp. 59 .

- ^ Carole Hillenbrand: The Crusades. Islamic Perspectives . University Press, Edinburgh 1999, ISBN 0-7486-0630-0 .

- ^ Sylvia Schein: Gateway to the Heavenly City: Crusader Jerusalem and the Catholic West (1099-1187) . Ashgate, 2005, ISBN 978-0-7546-0649-9 , pp. 19 .

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny : Translations and Translators. In: Robert L. Benson and Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century, pp. 421-462 . Harvard Univ. Pr., Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 978-0-19-820083-3 , pp. 422-6 .

- ^ Burgess Laughlin: The Aristotle Adventure. A Guide to the Greek, Arabic, and Latin Scholars Who Transmitted Aristotle's Logic to the Renaissance . Albert Hale Pub., Flagstaff, Arizona 1996, ISBN 978-0-9644714-9-8 , pp. 139 .

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 429 .

- ↑ Thomas E. Burman: Tafsir and Translation: Traditional Arabic Quran Exegesis and the Latin Qurans of Robert of Ketton and Mark of Toledo. In: Speculum. 73 (3), July 1998, pp. 703-732. JSTOR , accessed May 25, 2017.

- ^ Edward Said: Orientalism . Penguin Modern Classics, London, New York 2003, ISBN 978-0-14-118742-6 , pp. 59 .

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Ida & Walther von Wartburg (ex.): The divine comedy . Manesse, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-7175-1086-X , p. 334 .

- ^ Dante Alighieri, Ida & Walther von Wartburg (ex.): The divine comedy . Manesse, Zurich 2000, ISBN 3-7175-1086-X , p. 85 .

- ^ Edward Said: Orientalism . Penguin Modern Classics, London, New York 2003, ISBN 978-0-14-118742-6 , pp. 70-72 .

- ↑ Asunción Blasco Martínez: La expulsión de los judíos de España en 1492 . In: Kalakorikos: Revista para el estudio, defensa, protección y divulgación del patrimonio histórico, artístico y cultural de Calahorra y su entorno . No. 10 , 2005, pp. 13 f . (Spanish, dialnet.unirioja.es [accessed June 11, 2016]).

- ↑ Hans-Werner Goetz : The Perception of Other Religions and Christian-Occidental Self-Image in the Early and High Middle Ages. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-05-005937-2 (Volume 1) and ISBN 978-3-05-005937-2 (Volume 2)

- ^ Dieter Mertens: European peace and Turkish war in the late Middle Ages. In: Heinz Duchhardt (Hrsg.): Interstate peacekeeping in the Middle Ages and early modern times (Münsterische historical research, I) . Böhlau, Cologne 1991, ISBN 978-3-412-02490-1 , pp. 45–90, here p. 57 f .

- ↑ For example the Crusade of Smyrna a coalition of Cyprus , Venice and the Order of St. John (1344), the unsuccessful crusade of Humbert II. De la Tour-du-Pin against the Beylik of Aydın in 1345, and the capture of the city of Kallipolis by Amadeus VI in 1366 . of Savoy .

- ↑ Ernst Werner: Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror and the turning point in the 15th century. Berlin 1982, p. 29.

- ^ W. Brandes: The fall of Constantinople as an apocalyptic event. In: S. Kolwitz and RC Müller (eds.): Done and written. Studies in honor of Günther S. Henrich and Klaus-Peter Matschke . Eudora, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 978-3-938533-03-1 , pp. 453-469 .

- ^ Peter O'Brien: European perceptions of Islam and America from Saladin to George W. Bush. Europe's fragile ego uncovered . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK 2009, ISBN 978-0-230-61305-8 , pp. 75 .

- ^ Goffman: Ottoman empire and early modern Europe . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2002, ISBN 978-0-521-45908-2 , pp. 111 . online PDF , accessed on August 15, 2016.

- ↑ quoted from Robert J. Knecht: The Valois. Kings of France, 1328-1589 . Bloomsbury, London 2004, ISBN 978-1-85285-420-1 , pp. 144 .

- ^ Hans Schiltberger's online travel book , Heidelberg historical inventory

- ↑ Paul Srodecki: "Contre les ennemis de la foy de Dieu": The crusade of Nicopolis and the Western image of the Turks around 1400. In: Eckhard Leuschner, Thomas Wünsch (ed.): The image of the enemy. Construction of antagonisms and cultural transfer in the age of the Turkish wars . Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-7861-2684-3 , pp. 33-49 .

- ↑ See Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák and Tibor Frank: A History of Hungary. P. 99, as well as Klaus-Peter Matschke: The Cross and the Crescent. The history of the Turkish wars. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf a. a. 2004, pp. 317-320.

- ↑ a b Suraiya Faroqhi: In the face of the enemy? - The Ottoman Elite and Venice: An Overview of the Research Landscape. In: Eckhard Leuschner, Thomas Wünsch (Ed.): The image of the enemy. Construction of antagonisms and cultural transfer in the age of the Turkish wars . Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-7861-2684-3 , pp. 215-232 .

- ↑ Manuscript TSM H. 2324, Gülru Necipoğlu (2012): Visual cosmopolitanism and creative translation: Artistic conversations with Renaissance Itlay in Mehmet II's Istanbul. Muqarnas 29, pp. 1–81, here: p. 17

- ↑ TSM H.2153, Gülru Necipoğlu (2012): Visual cosmopolitanism and creative translation: Artistic conversations with Renaissance Itlay in Mehmet II's Istanbul. Muqarnas 29, pp. 1–81, here: pp. 18–19

- ↑ For contemporary miniature painting see Esin Atil: Ottoman Miniature Painting under Sultan Mehmed II. In: Ars Orientalis. Vol. 9, 1973, pp. 103-120.

- ↑ Jürg Meyer zur Capellen: Gentile Bellini at the court of Mehmet II. In: Neslihan Asutay-Effenberger, Ulrich Rehm (ed.): Sultan Mehmet II. Conqueror of Constantinople - patron of the arts. Cologne 2009, pp. 139–160.

- ^ Günsel Renda: Renaissance in Europe and sultanic portraiture. In: Robert Born, Michael Dziewulski, Guido Messling (Ed.): The Sultan's world: The Ottoman Orient in Renaissance art . Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2015, ISBN 978-3-7757-3966-5 , p. 37-43 .

- ↑ Gabór Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters: Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire: Illustrated manuscripts and miniature painting . Facts on File, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1 , pp. 268-269 . - online: PDF , accessed May 21, 2016

- ^ Julian Raby: From Europe to Istanbul. In: Selmin Kangal (Ed.): The Sultan's portrait: Picturing the House of Osman. Exhibition catalog. Is bankası, Istanbul 2000, ISBN 978-975-458-219-2 , pp. 136-163 .

- ↑ William J. Watson: "İbrāhīm Müteferriḳa and Turkish Incunabula", in: Journal of the American Oriental Society , Vol. 88, No. 3 (1968), pp. 435-441, here p. 436 "

- ↑ Stefano Carboni:, 2001: Glass from Islamic Lands . Thames & Hudson, London 2001, ISBN 978-0-500-97606-7 .

- ^ I. Fenlon: "In destructione Turcharum" . In: Francesco Degrada (ed.): Andrea Gabriele e il suo tempo. Atti del convegno internazionale (Venzia 16-18 September 1985) . LS Olschki, 1987 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ S. Skilliter: Three letters from the Ottoman 'sultana' Safiye to Queen Elizabeth I. In: SM Stern (Ed.): Documents from Islamic Chanceries (Oriental Studies No. 3) . University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC 1970, ISBN 978-0-87249-178-6 , pp. 119-157 .

- ^ SA Skilliter: William Harborne and the trade with Turkey, 1578-1582: A documentary study of the first Anglo-Ottoman relations . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1977, ISBN 978-0-19-725971-9 , pp. 69 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ cf. on this: Joseph Croitoru : The Germans and the Orient. Fascination, contempt and the contradictions of the Enlightenment . Hanser, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-446-26037-5 .

- ↑ Alexander Bevilacqua: The republic of Arabic letters - Islam and the European enlightenment . Belknap Press (Harvard University Press), 2018, ISBN 978-0-674-97592-7 , pp. 14-15 .

- ↑ a b c d Alexander Bevilacqua: The republic of Arabic letters - Islam and the European enlightenment . Belknap Press (Harvard University Press), 2018, ISBN 978-0-674-97592-7 , pp. 17-43 .

- ↑ Peter Kuhlmann: Jews and Turks - the old Luther and his dark sides . In: Martin Luther. Life - works - work . Regionalia Verlag, Rheinbach 2016, ISBN 978-3-95540-191-7 , p. 108-109 .

- ↑ Alexander Bevilacqua: The republic of Arabic letters - Islam and the European enlightenment . Belknap Press (Harvard University Press), 2018, ISBN 978-0-674-97592-7 , pp. 46 .

- ↑ Alexander Bevilacqua: The republic of Arabic letters - Islam and the European enlightenment . Belknap Press (Harvard University Press), 2018, ISBN 978-0-674-97592-7 , pp. 44-74 .

- ^ Donald Quataert: The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2000, ISBN 978-0-521-83910-5 , pp. 6-11 . Full text , accessed August 13, 2016.

- ↑ Mustafa Soykut: Historical image of the Turk in Europe, 15th century to the present: Political and civilizational aspects . Isis, Istanbul 2010, ISBN 978-1-61719-093-3 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Elias Kolovos, Phokion Kotzageorges, Sophia Laiou, Marinos Sariyannis (eds.): The Ottoman Empire, the Balkans, the Greek lands, Studies in honor of John C. Alexander . Isis, 2007, ISBN 978-975-428-346-4 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Vatican Radio : Spain: Against the Mosque Church ( Memento of October 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), December 28, 2006

- ^ Controversy over the future of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. ( Memento from January 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) on: zeit.de , December 27, 2013.

- ^ Ossama Hegazy: Towards a 'German mosque': rethinking the mosque's meaning in Germany via applying socio-semiotics . Bauhaus University Weimar, Institute for European Urban Studies (IfEU), Weimar 2015, ISBN 978-3-89574-878-3 .

- ↑ a b c Peter Carstens: Much more Muslims than expected FAZ.net from June 24, 2009.

- ↑ Islam in the demographic boom , FOCUS Online, March 31, 2007

- ↑ The Fischer World Almanac current. Russia and the Caucasus. Frankfurt 2005

- ^ Frisch / Hengelhaupt / Hohm: Pocket Atlas European Union. Gotha 2007 (total of the country-specific figures on pages 73–203)

- ↑ Turkish Statistical Institute (2007): title = 2007 Census, population by provinces and districts , December 26, 2007

- ↑ census in Bosnia and Herzegovina from the year 2013: BH Description 2013. In: www.popis2013.ba. Retrieved September 10, 2016 .

- ↑ all figures from Frisch / Hengelhaupt / Hohm: Pocket Atlas European Union. Gotha 2007, pages 199, 81, 91, 121, 73, 87 and 147

- ^ Fischer Weltalmanach 2009, page 349. Frankfurt / Main 2008

- ^ Fischer Weltalmanach 2009, page 72. Frankfurt / Main 2008

- ^ Fischer Weltalmanach 2009, page 359. Frankfurt / Main 2008

- ↑ Isabella Ackerl : The States of the Earth - Europe and Asia, p. 97. Wiesbaden 2007

- ↑ Paul Statham & Jean Tillie: Muslims in their European societies of settlement: a comparative agenda for empirical research on socio-cultural integration across countries and groups . (Muslims in European Societies: Comparative Agenda for Empirical Research into Socio-Cultural Integration in Different Societies and Groups). In: Routledge, Tailor and Francis Group (Eds.): Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies . tape 42 , 2016, p. 177-196 , doi : 10.1080 / 1369183X.2015.1127637 .