Latin translations in the High Middle Ages

Latin translations were created during the high medieval "Renaissance" in the course of the acquisition of new, especially Greek and Arabic-language sources of knowledge by European scientists. In the late 11th century, the areas of the Taifa Kingdom of Toledo (1085) and Sicily , which had previously been ruled by Muslim Arabs, were conquered by Christian rulers. The remaining Arab scholars, a largely Arabic-speaking population, and the new Christian rule offered a new approach and favorable starting conditions for the work of European scholars who wrote Latin. A typical example is the biography of Gerhard von Cremonas (approx. 1114–87): He had traveled to Toledo because he considered the Latin source works available to him on the Almagest of Claudius Ptolemy to be inadequate. When he found Arabic textbooks there that were superior in scope and content to the works available in Latin, he decided to learn Arabic and translate the books.

prehistory

While Islamic scholars began to translate Greek and Latin authors of late antiquity shortly after the Islamic expansion and to expand them with their own ideas, Christian authors such as Jerome were opposed to the "pagan" philosophy of Aristotle, for example. This attitude was one of the reasons for book losses. The lack of literature of the great Greek philosophers and their translation was countered in the 6th century by Cassiodorus , who in 535 had agreed with Pope Agapit to found a library of church authors in Greek and Latin. This library was created as part of Cassiodor's educational project in the Vivarium monastery , where Latin translations were made. Soon after Cassiodor's death, the library was closed. Only for a short time, during the Carolingian Renewal , had philosophical works of Greco-Roman antiquity been discussed in Europe by scholars such as Alcuin . Overall, philosophical thinking made little progress in early medieval Europe . This only changed with the advent of scholasticism in the 12th century and the emergence of the first European universities. Their libraries collected preserved ancient writings and provided a place where the newly available ideas could be discussed.

With the Christian conquests of the 12th century (Toledo, 1085; Sicily, 1091; Jerusalem , 1099) areas with a long tradition of multilingualism became accessible to Christian scholars; the multilingualism made translating easier. In Sicily, which has existed since 212 BC It had been a Roman province and was under Byzantine rule until the 10th century , Greek works could be translated directly into Latin. The Spanish Toledo, which had been under Arab rule as part of al-Andalus since 711, offered ideal conditions for translations from Arabic into Latin.

In contrast to the interest of the Renaissance in the works of classical antiquity , the translators of the 12th century were more interested in knowledge from Islamic science and philosophy , and to a lesser extent in religious and literary works.

Translations in Italy

Monte Cassino

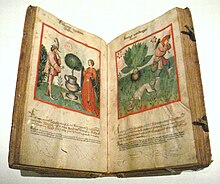

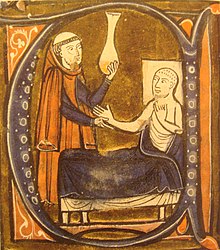

In the 11th century, Constantine the African , a Christian from Carthage , studied medicine in early Islamic Egypt . As a monk in the monastery of Monte Cassino in Italy, he later translated works of Islamic medicine from Arabic. Among other things, he translated al-Majusi's medical encyclopedia “Complete Book of Medical Art” ( Kitāb Kāmil aṣ-Ṣināʿa aṭ-Ṭibbiyya ) as “Liber pantegni” ( koiné-Greek pantéchni means “the entire art of healing”). This work was one of the textbooks that were on the curriculum at the school in Salerno . A more complete and accurate translation was made by Stephen of Antioch in 1127. The work was widespread and was printed in Venice in 1492 and 1523 . He also translated the Isagoge ad Tegni Galeni by Hunain ibn Ishāq and his nephew Hubaysh ibn al-Hasan., The Liber de febribus , Liber de dietis universalibus et particularibus and Liber de urinis by Isaak ben Salomon Israeli , Ishaq ibn Imran's psychological textbook al- Maqala fi al-Malikhukiya as De melancolia , as well as Ibn al-Jazzar's books De Gradibus, Viaticum, Liber de stomacho, De elephantiasi, De coitu and De oblivione .

Sicily

Sicily belonged to the Byzantine Empire until 878 , was under Islamic rule from 878-1060 as an emirate of Sicily, and between 1060 and 1090 under Norman rule. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily remained trilingual and was therefore a suitable place for translation work, especially since relations with the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire continued to exist.

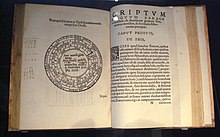

A copy of the Almagest of Claudius Ptolemy was brought to Sicily as a gift from the Byzantine emperor Manuel I (Byzantium) to William I of Sicily by Henricus Aristippus , who was ambassador to Byzantium from 1158 to 1160. Aristippus translated Plato's Meno and Phaedo into Latin; a Latin translation of the Almagest , as well as some works by Euclid , the fourth book of the Meteorologica by Aristotle and works by Gregory of Nazianzen from the Greek was made by an unknown student from the school of Salerno. Later, Gerhard of Cremona published a more complete translation of the Almagest from Arabic. In Sicily, translations were usually carried out directly from Greek; only when Greek texts were not available, Arabic texts were used and translated. Eugenius of Palermo , a high Sicilian official ( Ammiratus ) of the kingdom, translated Ptolemy's optics , making use of his knowledge of all three languages. Accursius of Pistoia translated works by Galen and Hunain ibn Ishāq . Gerard de Sabbioneta translated Avicenna's canon of medicine and al-Razi's Almansor . With his Liber Ab (b) aci (1202), Leonardo Fibonacci presented the first European treatise on the Indian numerals from Arabic sources. The aphorismi of Yuhanna ibn Masawaih (Mesue) were translated by an unknown translator in the late 11th or early 12th centuries.

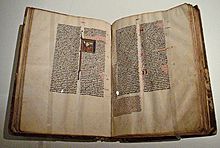

Jacob of Venice , who may have spent a few years in Constantinople, became known as the authoritative translator of Aristotle from ancient Greek into Latin. Numerous copies that have survived from the 13th century bear the reference to translatio Jacobi . The first Greek-Latin translations of the Physica , the Metaphysica (Book I to Book IV, 4, 1007a31) and De anima are ascribed to him . The translation of parts of the Parva naturalia is also assigned to him (in particular the translatio vetus of De morte et vita , De memoria , De juventute and De respiratione ), as well as the new text versions of the Topica , De sophisticis elenchis (fragments), already translated by Boethius , the Analytica priora and posteriora . The translations of the latter are widespread throughout the Middle Ages: 275 known manuscripts come from him, but only eight from the three other known translators. Fragments of a commentary on the Elenchis and the Analytica posteriora are also associated with his name . In doing so, he had made the corpus of Aristotle's logical texts, the Organon , completely available in Latin.

In the 13th century Bonacosa translated in Padua Averroes ' medical textbook Kitab al-Kulliyyat as Colliget , and John of Capua , the Kitab al-Taysir of Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) as Theisir . In Sicily, Faraj ben Salim al-Hawi translated from Rhazes as Continens , as well as the Tacuinum sanitatis by Ibn Butlan . Simon of Genoa and Abraham Tortuensis translated Abulcasis At-Tasrif as Liber servitoris , Alcoatis Congregatio sive liber de oculis and the Liber de simplicibus medicinis by Serapion the Younger.

Translations in the Spanish-Arabic border area

Early translations

As early as the end of the 10th century, European scholars were traveling to Spain to study. One of these was Gerbert von Aurillac , who later became Pope Silvester II, who studied mathematics in the Spanish Mark . He was already familiar with the Aristotle commentaries by Boethius . The translations that arose during this period mainly dealt with the works of Islamic mathematicians and astronomers, but also with religious texts such as the Koran . Most of the translations were done from Arabic, often with the help of Arabic-speaking locals.

The most important translations were made under Petrus Venerabilis , the 9th abbot of Cluny Abbey . In 1142 he commissioned Robert von Ketton , the baptized Jewish scholar Petrus Alfonsi, and the monk Hermann von Carinthia with the first Latin translation of the Koran, the Lex Mahumet pseudoprophetae . He pursued the goal of refuting the religion of Islam from its sources, and for this purpose wrote his works Summa totius heresis Saracenorum ("Sum of the heresies of the Saracens") and Liber contra sectam sive heresim Saracenorum ("Against the sect or heresy of the Saracens ”). Further Islamic works were translated, including al-Kindī , and together they formed the Corpus toletanum , one of the most influential collections of works in the discussion of Islam in the High Middle Ages. In Catalonia had Plato of Tivoli , Herman of Carinthia in Northern Spain and the Languedoc , Hugh of Santalla in Aragon , Robert of Ketton in Navarre and Robert of Chester in Segovia .

Plato of Tivoli's translations include al-Battanis astronomical and trigonometric work De motu stellarum , Abraham bar Chijas Liber embadorum , Theodosius of Bithynia Spherica , and treatise on the loop measurement of Archimedes . Robert von Chester translated, among other things, al-Chwarizmis Ḥisāb al-ğabr wa-ʾl-muqābala , on whose Latin title Ludus algebrae almucgrabalaeque the word " algebra " goes back, as well as astronomical and trigonometric tables. Abraham of Tortosa translated Ibn Sarabis (Serapion the Younger) De Simplicibus and Abulcasis At-Tasrif as Liber Servitoris . In 1126, Muhammad al-Fazaris Sindhind , which itself is a summary of Indian astronomical works ( Surya Siddhanta and Brahmaguptas Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta ).

In addition to | of philosophical and scientific literature, the Jewish scholar Petrus Alfonsi translated a collection of Arabic stories into Latin. Some of these stories come from the Panchatantra and the Arabian Nights Collection , including the story of " Sindbad the Navigator ".

Toledo School of Translators

Toledo , with its Arabic-speaking Christian ( Mozarabic ) inhabitants, had been a center of learning since the end of the 10th century, and was already being visited by European scholars at that time. Among the earliest translators are Abraham ibn Daud (Avendauth), who translated Avicenna's medical encyclopedia Kitāb al-Shifā ( Book of Healing ) in collaboration with Dominicus Gundisalvi , Archdeacon of Cuéllar (near Segovia ) .

A separate school of translators only formed after the conquest of Toledo in 1085: According to tradition, Raimund of Toledo set up a translator group in Toledo Cathedral , which included Mozarabs from Toledo, Jewish scholars, teachers of Islamic Madāris and monks of the Order of Cluny . They worked on translations from Arabic into Castilian, Castilian into Latin, or straight from Arabic into Latin or Greek. He placed particular emphasis on the texts of Arab and Jewish philosophers, which should contribute to the understanding of Aristotle . The Toledo Cathedral Library became known as the Escuela de Traductores de Toledo Translation Center ( Toledo School of Translators ) and played an important role in European culture.

One of the most productive translators from Toledo was Gerhard von Cremona , of whom 87 translated works are known. Below are: The Almagest. of Ptolemy; Works by Aristotle, including Analytica posteriora , Physik , Über den Himmel , De generatione et corruptione , and Meteorologie; al-Chwarizmi's Ḥisāb al-ğabr wa-ʾl-muqābala ; Archimedes' "Treatise on Circular Measurement" ; Euclid's "elements" ; Jabir ibn Aflah's Elementa astronomica ; al-Kindīs optics ; Farghanis On the Elements of Astronomy and Celestial Movements al-Fārābī's classification of the sciences. the alchemical and medicinal works of ar-Rāzī , works of Thabit ibn Qurra and Hunain ibn Ishāq ; az-Zarqali ; Jabir ibn Aflah; the Banū Mūsā brothers; Abu Kamil ; Abulcasis and Alhazen . Among the medical works he has translated are Ali ibn Ridwan's Expositio ad Tegni Galeni ; the Practica, Brevarium medicinae by Yahya ibn Sarafyun (John Serapion or Serapion the Elder); al-Kindīs De Gradibus ; ar-Rāzīs Liber ad Almansorem, Liber divisionum, Introductio in medicinam, De egritudinibus iuncturarum, Antidotarium and Practica puerorum ; Isaak ben Salomon Israelis De elementis and De definitionibus ; Abulcasis At-Tasrif as Chirurgia ; Avicenna's canon of medicine as Liber Canonis ; and the Liber de medicamentis simplicus of Ibn al-Wafid (Abenguefit).

In the late 12th and early 13th centuries, Mark of Toledo again translated the Koran and various medical textbooks, including Hunain ibn Ishāqs Liber isagogarum .

The importance of the School of Toledo increased under King Alfonso X of Castile . He had insisted that the translations had to be "llanos de entender" ("easy to understand"). The translations from Toledo reached European scholars from many countries.

Michael Scotus (approx. 1175-1232) translated in 1217 the Kitāb fi l-haiʾa of Nur ad-Din al-Bitrudschi (Latin Alpetragius) as De motibus coelorum ("The movements of the heavens") and before 1220 the three existing Arabic Books Historia animalium. De partibus animalium and De generatione animalium des Aristotle , which, when used by Albertus Magnus for his De animalibus , gained great influence. Although Wilhelm von Moerbeke completed his translations directly from the Greek on December 23, 1260, those by Michael Scotus were still used in the universities in the 15th century. His fame as a translator is mainly based on the translations of Averroes' commentaries on Aristotle's writings such as De anima , De sensu et sensato , De celo et mundo , Physica and Metaphysica . A total of 14 translations of Averroes' comments have been preserved.

other European countries

David the Jew (fl. 1228–1245) translated works from ar-Rāzī into Latin. Arnaldus de Villanova (1235-1313) translated works by Galen and Avicenna , including his Maqala fi Ahkam al-adwiya al-qalbiya as De viribus cordis , De medicinis simplicibus by Abu al-Salt (Albuzali), and Qusta ibn Luqas De physicis ligaturis .

In Portugal in the 13th century Giles translated from Santarém ar-Rāzīs De secretis medicine, Aphorismi Rasis and Mesues De secretis medicine . In Murcia , Rufin of Alexandria worked on a translation of the Liber questionum medicinalium discentium in medicina by Hunain ibn Ishāq , and Dominicus Marrochinus on the Epistola de cognitione infirmatum oculorum by Ali ibn Isa al-Asturlabi (Jesu Haly). In Lleida , Johannes Jacobi translated Alcoati's medical work Liber de la figura del uyl into Català and then into Latin.

Wilhelm von Moerbeke (approx. 1215–1286) was a prolific translator of philosophical, medical and scientific texts from Greek into Latin. At the request of Thomas Aquinas , he undertook a complete translation of Aristotle's writings or a revision of already existing texts. He is considered to be the first translator of Aristotle's politics . Moerbeke's translations were standard texts as early as the 15th century, when Hendrik Herp noted that the translation was both literal ( de verbo in verbo ), true to the spirit of Aristotle, and “without elegance”. The original Greek texts of some of Wilhelm's translations were lost over time, so that they would have disappeared without his work. Wilhelm also translated mathematical treatises by Heron of Alexandria and Archimedes . Of particular importance was his translation of the foundations (elements) of the theology by Proklos (1268), one of the most important source works of Neo-Platonism in the 13th century. The Vatican Apostolic Library has Wilhelm's own copy of his Archimedes translation, with commentaries by Eutocius , which was written in 1269 at the papal court in Viterbo. For his work Wilhelm used two of the best Greek Archimedes manuscripts, which have since been lost.

Adelard von Bath's ( fl. 1116–1142) Latin translations include al-Khwarizmi's Astronomical Tables and his Liber ysagogarum Alchorismi ; the introduction to the astrology of Abū Ma'shar , as well as Euclid's elements . Adelard worked with other West English scholars such as Petrus Alfonsi and Walcher von Malvern on the translation and further development of astronomical concepts from Spain. Even Abu Kamil's Algebra was translated into Latin at that time, the name of the translator is unknown.

Alfred von Sareshel (approx. 1200-1227) translated Nikolaos of Damascus and Hunain ibn Ishāq . Antonius Frachentius Vicentinus translated Avicenna ; Armenguad Avicenna, Averroes , Hunain ibn Ishāq and Maimonides ; Berengarius of Valentia Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis); Drogon (Azagont) al-Kindī ; Farragut (Faradj ben Salam) in turn Hunain ibn Ishāq, Ibn Zezla (Byngezla), Māsawaih (Mesue), and ar-Rāzī (Rhazes). Andreas Alphagus Bellnensis translated Avicenna, Averroes, Serapion the Younger, al-Qifti and Albe'thar, among others.

In Montpellier Profatius and Bernardus Honofredi translated the Kitab alaghdiya of Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) as De regimine sanitatis ; Armengaudus Blasius translated the al-Urjuza fi al-tibb , a compilation of the writings of Avicenna and Averroes, as a cantica cum commento .

Other works that were translated during this period include alchemical texts by Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber), whose treatises became standard works by European alchemists. Among them are the Kitab al-Kimya ( Book of the Elements of Alchemy ), 1144 by Robert von Chester (1144).

Hebrew translations

In the south of France and Italy, texts were translated into Hebrew in the 12th century . These in turn were used by other translators such as Profatius Judas to produce Latin translations. This practice was maintained until the 16th century.

See also

- Loss of books in late antiquity

- Graeco Arabica

- Toledo School of Translators

- High medieval renaissance

- Islam in Europe

Individual evidence

- ^ Houtsma, p. 875.

- ^ Burgess Laughlin: The Aristotle Adventure. A Guide to the Greek, Arabic, and Latin Scholars Who Transmitted Aristotle's Logic to the Renaissance . Albert Hale Pub., Flagstaff, Arizona 1996, ISBN 0-9644714-9-3 , pp. 139 .

- ^ Günter Ludwig : Cassiodor. About the origin of the occidental school. Frankfurt a. M. 1967, pp. 13 and 17

- ↑ cf. Günter Ludwig: Cassiodor ... , 1967, pp. 45, 119f

- ^ Burgess Laughlin: The Aristotle Adventure. A Guide to the Greek, Arabic, and Latin Scholars Who Transmitted Aristotle's Logic to the Renaissance . Albert Hale Pub., Flagstaff, Arizona 1996, ISBN 0-9644714-9-3 , pp. 143-146 .

- ^ Burgess Laughlin: The Aristotle Adventure. A Guide to the Greek, Arabic, and Latin Scholars Who Transmitted Aristotle's Logic to the Renaissance . Albert Hale Pub., Flagstaff, Arizona 1996, ISBN 0-9644714-9-3 , pp. 147-148 .

- ↑ David C. Lindberg (Ed.): Science in the Middle Ages . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1978, pp. 58-59 .

- ^ A b Robert Irwin: The Arabian Nights: A Companion . Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2004, ISBN 1-86064-983-1 , pp. 93 .

- ↑ a b c Jerome B. Bieber: Medieval Translation Table 2: Arabic Sources. ( Memento of the original from March 18, 2001 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Santa Fe Community College, Florida, accessed May 29, 2016.

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny : Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 422-426 .

- ^ Gundolf Keil: The German Isaak Judäus reception from the 13th to the 15th century. (= European Scientific Relations. Supplement 2). Shaker, Aachen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8440-3933-7 , p. 25 f. with note 132.

- ↑ Charles SF Burnett, Danielle Jacquart (ed.): Constantine the African and ' Alī Ibn Al ' Abbās al-Magusi: The Pantegni and Related Texts . Brill, Leiden 1995, ISBN 90-04-10014-8 .

- ↑ a b Danielle Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West . In: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 981 .

- ↑ a b c d e Donald Campbell: Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages . Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-415-24463-3 , pp. 3–6 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - reprint of the London 1926 edition).

- ^ Charles Homer Haskins : Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science . Frederick Ungar Publishing, New York 1967, p. 155-157 . (online) , accessed May 26, 2016.

- ↑ Donald Matthew: The Norman kingdom of Sicily . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1992, ISBN 0-521-26284-4 , pp. 118 .

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 433-434 .

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators. In: Robert L. Benson and Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 435 .

- ↑ Danielle Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West . In: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 963-984 .

- ↑ Coloman Viola: L'Abbaye du Mont Saint-Michel et la preparation intellectuelle du grand siècle . 1970. (online) , accessed May 26, 2016.

- ^ Steven J. Livesey: James of Venice. In: Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia . Routledge, 2005, ISBN 1-135-45932-0 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ LD Reynolds, Nigel G. Wilson: Scribes and Scholars. Oxford 1974, p. 106.

- ↑ Danielle Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West . In: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 983 .

- ↑ Danielle Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West . In: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 984 .

- ^ Burgess Laughlin: The Aristotle Adventure. A Guide to the Greek, Arabic, and Latin Scholars Who Transmitted Aristotle's Logic to the Renaissance . Albert Hale Pub., Flagstaff, Arizona 1996, ISBN 0-9644714-9-3 , pp. 141 .

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 429-430, 451-452 .

- ^ Charles Homer Haskins: Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. P. 288.

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 429 .

- ↑ Thomas E. Burman: Tafsir and Translation: Traditional Arabic Quran Exegesis and the Latin Qurans of Robert of Ketton and Mark of Toledo. In: Speculum. 73 (3), July 1998, pp. 703-732. JSTOR , accessed May 26, 2016.

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 429-330, 451-452 .

- ^ A b c V. J. Katz: A History of Mathematics: An Introduction. 1998, p. 291.

- ^ GG Joseph: The Crest of the Peacock. 2000, p. 306.

- ↑ Cristiano Leone (ed.); Pietro Alfonsi: Alphunsus de Arabicis eventibus. (= Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Anno CDVIII-Classe di Scienze morali, storiche e filologiche. Memorie Series IX - Volume XXVIII - Fascicolo 2). Studio ed edizione critica. Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rome 2011, ISBN 978-88-218-1039-1 .

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 444-446, 451 .

- ^ René Taton: History of Science: Ancient and Medieval Science . Basic Books, New York 1963, pp. 481 .

- ^ C. Burnett: Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo. 2001, pp. 249-251, 270.

- ^ CH Haskins: Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, p. 287: "More of Arabic science passed into Western Europe at the hands of Gerard of Cremona than in any other way."

- ^ Charles Burnett: The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century. In: Science in Context. 14, 2001, pp. 275-281.

- ↑ Muhammedis Fil. Ketiri Ferganensis, qui vulgo Alfraganus dicitur, Elementa Astronomica: arabice & latine cum notis ad res exoticas sive orientales, quae in iis occurrunt. Opera at e-rara

- ^ A. Mark Smith: Alhacen's Theory of Visual Perception: a critical edition with English translation and commentary of the first three books of Alhacen's "De Aspectibus", the medieval Latin version of Ibn al-Haytam's "Kitab al-Manazir." Part 1 In: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 91, 4, 2001, pp. Clxviii. JSTOR

- ^ A b c d Danielle Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West . In: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 983 .

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 429, 455 .

- ↑ Miguel Hernando de Larramendi: La traducción de literatura árabe contemporánea . Univ. de Castilla La Mancha, 2000, ISBN 84-8427-050-5 , p. 109 .

- ^ William PD Wightman: The Growth of Scientific Ideas . Yale University Press, New Haven 1953, ISBN 1-135-46042-6 , pp. 332 .

- ^ FJ Carmody (ed.); al-Bitruji: De motibus coelorum. University of California Press, Berkeley 1952.

- ↑ Christoph Kann: Michael Scotus. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 5, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-043-3 , Sp. 1459-1461.

- ↑ a b Danielle Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West . In: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 984 .

- ^ Marshall Clagett: Archimedes in the Middle Ages. Volume 1, Madison 1964, pp. 3, 658f .; Wilbur Richard Knorr: Textual Studies in Ancient and Medieval Geometry. Boston 1989, p. 127 note 132; Richard Lorch: The Arabic Transmission of Archimedes 'Sphere and Cylinder and Eutocius' Commentary. In: Journal for the History of Arabic-Islamic Sciences. 5, 1989, pp. 106-108, 114.

- ^ Charles Burnett (Ed.): Adelard of Bath, Conversations with His Nephew. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999, p. Xi.

- ^ CH Haskins: Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge 1927, pp. 112-117.

- ^ SC McCluskey: Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge 1998, pp. 180-184.

- ↑ Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 , pp. 440-443 .

- ↑ David C. Lindberg (Ed.): Science in the Middle Ages . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1978, pp. 69 .

literature

- Charles Burnett: The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century. In: Science in Context. 14, 2001, pp. 249-288.

- Donald Campbell: Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages . Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-415-24463-3 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - reprint of the London 1926 edition).

- Marie-Thérèse d'Alverny: Translations and Translators . In: Robert L. Benson, Giles Constable (Eds.): Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, ISBN 0-19-820083-8 .

- Charles Homer Haskins: The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century . Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge 1927, Chapter 9: The Translators from Greek and Arabic.

- Charles Homer Haskins: Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science. Frederick Ungar Publishing, New York 1967. (Reprint of the Cambridge, Mass. Edition, 1927)

- George G. Joseph: The Crest of the Peacock. Non-European Roots of Mathematics . Princeton University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-691-00659-8 .

- Victor J. Katz: A History of Mathematics: An Introduction . Addison-Wesley , 1998, ISBN 0-321-01618-1 .

- Burgess Laughlin: The Aristotle Adventure. A Guide to the Greek, Arabic, and Latin Scholars Who Transmitted Aristotle's Logic to the Renaissance . Albert Hale Pub., Flagstaff, Arizona 1996, ISBN 0-9644714-9-3 .

- David C. Lindberg (Ed.): Science in the Middle Ages . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1978.

- Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed: Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 .

- W. Montgomery Watt: The Influence of Islam on Medieval Europe . University Press, Edinburgh 1972, ISBN 0-85224-218-2 .

Web links

- Robert von Ketton's Translation of Qu'ran, 1550 edition , accessed May 29, 2016.

- Norman Roth: Jewish Collaborators in Alfonso's Scientific Work. In: Robert I. Burns (Ed.): Emperor of Culture: Alfonso X the Learned of Castile and His Thirteenth-Century Renaissance Culture. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8122-8116-0 . accessed May 29, 2016.

- George Sarton: A Guide to the History of Science. Waltham, Mass. 1952, p. 27 ff. (PDF), accessed May 29, 2016.