Medicine in the Medieval Islamic World

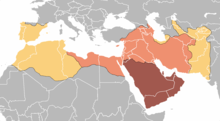

The medicine in the medieval Islamic world describes the healing of the Middle Ages in the Middle East , North Africa and Andalusia from the seventh to the thirteenth century, as it was passed down primarily in Arabic. It is based on the knowledge and ideas of ancient Greco-Roman and later Byzantine medicine , systematized, interpreted and partially supplemented them.

Islam , which has spread since the 7th century , reached a large part of the world known in Europe, Africa and Asia by the end of the period under consideration. In the different regions of the Islamic world, different medical traditions or schools developed over time. Arabic as the common language of the Islamic civilization was also used by Jewish, Christian and other doctors and marks the medicine of the Islamic cultural area, which is therefore also referred to as "Arabic" or "Arabic-Persian" and "Arabic-Islamic" medicine.

The medicine of the time recorded in Arabic influenced the doctors of the Western Middle Ages , who first got to know the works of classical Greco-Roman (especially Galenic ) medicine in Arabic translation (the communication of Arabic philosophy and science to the Christian West often took place about Jewish authors). It was not until the 12th century that these writings were translated into Latin , the common language of Western European science. Works by Jewish and Islamic doctors, such as the medical canon of Avicenna (980-1037), which summarized the knowledge of the time , have been part of the standard textbooks of doctors for centuries.

The authority of the medieval doctors of the Islamic culture only waned in the course of the rise of scientific research in the wake of the Enlightenment . Her thoughts on the doctor-patient relationship are still quoted today, and her memory is also respectfully preserved by modern doctors.

history

Emergence

Only in the Middle East the tradition of until the 19th century fundamental in the West had "four humors" of Hippo crater and Galen uninterrupted passed. Certainly the Arabs had some knowledge of medicine before they came into contact with the Greco-Roman medical tradition. The names of some pre- and early Islamic doctors are known, even if little of their knowledge has survived. Fundamental for an Arabic medicine based on Greek natural philosophy was the reception of Aristotle by the philosophical-theological academy in Gondeschapur , which had existed since the 3rd century , where a medical faculty was established around 555 under Chosrau Anuschirwān .

aṭ-Ṭibb an-Nabawī - The Prophetic Medicine

Traditions about sayings and habits of the Prophet Mohammed were recorded by the following generations partly in their own records, partly in the tradition of the hadiths . Under the title aṭ-Ṭibb an-Nabawī ( Arabic الطب النبوي- “The prophetic medicine”) these traditions were later collected and handed down as independent works. Ibn Chaldūn gives an overview in his work Muqaddima, but separates the medicine, which he sees as a craft, from the theological sciences:

“You must know that the origin of all illnesses goes back to nutrition, like the prophet - God bless him and give him salvation! - in the tradition that covers all of medicine, as it is done among medical professionals, says, even if the religious scholars contest it. These are his words: the stomach is the house of sickness and abstinence is the main medicine. The cause of all illness is impaired digestion. "

A marginal note in Saheeh al-Buchari , a collection of hadiths by the scholar al-Buchari , indicates that there was a record of Muhammad's medical sayings from his younger contemporary Anas bin-Malik. Anas reports of two doctors who treated him with the branding iron and mentions that the Prophet wanted to avoid this treatment in another case of illness and asked whether other effective drugs were known. It is reported from later times that the caliph ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān fastened his teeth with gold wire. Brushing your teeth with a stick ( miswāk ) is also mentioned as a pre-Islamic custom.

The “medicine of the prophet” received little attention from the classical authors of Islamic medicine, but lived on for several centuries in the materia medica , which is partly based on the empirical medicine of the Bedouins. In his Kitab aṣ-Ṣaidana (Book of Remedies) from 10./11. In the 19th century, al-Biruni repeatedly referred to collections of poetry and works that describe and comment on the materia medica of the ancient Arabs.

The most famous doctor and contemporary of the Prophet was al-Ḥariṯ ben-Kalada aṯ-Ṯaqafī . He is said to have been connected to the Persian Academy of Gundischapur , perhaps even to have studied there. The sources document a conversation about medical matters with Khosrau I. Anuschirwan. At Muhammad's own request, ben-Kalada is said to have treated one of the Prophet's companions ( Sahāba ), so that it can be assumed that Mohammed also knew the reputation of the academy and made use of trained doctors there.

Early doctors under Islamic rule

The first contact with ancient or late Hellenistic knowledge probably came not through translations, but through direct contact with doctors who practiced in the newly conquered areas. Moving the capital to Damascus may have made contact easier. The names of two Christian doctors have been handed down from the early Islamic period: Ibn Aṯāl was the personal physician at the court of the Umayyad caliph Muʿāwiya I. The caliph misused his knowledge to get rid of some of his enemies with poison. In the service of Muʿāwiyas was Abu l-Arzneakam, who was responsible for the preparation of medicines. The son, grandson and great-grandson of Abu l-Ḥakam also worked at the courts of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs .

These and other sources testify that an intensive occupation with medicine took place as early as the Umayyden period. Medical knowledge very likely found its way into the emerging culture of the Islamic world from Alexandria , perhaps through Syrian scholars or translators.

7th-9th Century: absorption and appropriation

Few sources provide information about where the expanding Islamic community got their medical knowledge from. It is said that Abū Ramṯa went to Egypt. A doctor from the Iraqi Kufa named Abdalmalik ben Abgar al-Kinānī is said to have worked in Alexandria in pre-Islamic times and then joined the later caliph ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz . ʿUmar eventually moved the medical school from Alexandria to Antioch . It is also known that members of the medical school from Gundischapur traveled to Damascus. Nevertheless, this school remained active until the time of the Abbasid Caliphs.

The "Book of Poisons", written in the second half of the 8th century by a doctor named Jabir ibn Hayyan (Gabir), is of importance for research into early Islamic medicine . This was based solely on the medical literature available to him in Arabic translation. He mainly quotes Hippocrates , Plato , Galen , Pythagoras and Aristotle , only the names of some drugs and medicinal plants are taken from Persian.

In 825 the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma'mūn founded the House of Wisdom ( Arabic بيت الحكمة Bayt al-Hikma , DMG bait al-ḥikma ) in Baghdad based on the model of the Academy of Gundischapur. Under the direction of the Christian doctor Hunayn ibn Ishaq and with the help of Byzantium , all discoverable works of antiquity have been translated, including by Galen , Hippocrates , Plato , Aristotle , Ptolemy and Archimedes . Hunain's son Ishāq ibn Hunain also worked here as a translator of Euclid's elements with the mathematician and astronomer Thabit ibn Qurra, who also worked there. Al-Abbas ibn Said al-Jawhari , the philosopher al-Kindī , the Banū Mūsā brothers and the mathematician al-Khwarizmi also worked in the House of Wisdom. A hospital was also attached to the house.

Today it is assumed that the early Islamic medicine was mainly informed directly from the Greek sources of the School of Alexandria in Arabic translation; the influence of the Persian school seems to have been less pronounced, at least on medical theory, although the Persian doctors were also familiar with the ancient literature.

10th century

Islamic medicine reached its first heyday in the 10th century. Famous doctors of the time included:

- Rhazes (864-925); Liber continens , Liber medicinalis

- Haly Abbas ; Liber regalis

- Isaac Judaeus (840 / 850-932); Books on medical theory, diet , uroscopy and fever

- Avicenna (980-1037); Canon medicinae

The Canon medicinae of Avicenna became the basic medical work of the Middle Ages because of its closed and uniform presentation.

11-12 century

Islam reached today's Spain via North Africa . In Córdoba , a cultural center, which passed the most prestigious universities of the tenth century was, as well as 70 public libraries and 50 hospitals. The first peaceful amalgamation of Islamic, Jewish and Christian traditions for the benefit of medicine took place here. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, in Islamic-ruled Spain (" al-Andalus "), medicine developed that was characterized by more independence in theory and practice, especially in the areas of medical theory , botany , dietetics , drug science , materia medica and surgery. The most important representatives include:

- Abulcasis (936-1013); in the field of surgery

- Averroes (1126-1198); Medical philosophy

- Maimonides (1135 / 1138–1204)

swell

Ancient and late Hellenistic medicine

Ancient sources

Individual works and compilations of ancient medical works by various Arabic translators are known as early as the 7th century. Hunain ibn Ishāq , the head of the translator group in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, played an essential role in the translation of the ancient authors . In addition to the great medical works of Hippocrates and Galenus , works by Pythagoras of Samos, Akron of Agrigento, Democritus , Polybos, Diogenes of Apollonia , the medical writings ascribed to Plato , Aristotle , Mnesitheos of Athens , Xenocrates , Pedanios Dioskurides , Soranos of Ephesus , Archigenes were published , Antyllos , Rufus of Ephesus translated directly, other works such as that of Erasistratos were known through quotations in Galen's works.

Late Hellenistic sources

The works of Oreibasios , personal physician to the Roman emperor Julian , who lived in the 4th century AD, were well known and were cited in detail by Rhazes in particular . The works of Philagrius, also from the 4th century, are only known to us today in quotations from Islamic doctors. 400 years later, Rhazes ascribes the role of commentator to the “Summaria Alexandrinorum”, a summary of the 16 books of Galen, which is strongly influenced by superstitious ideas, from the 6th century philosopher and doctor Johannes Grammaticus . Also involved in the "Summaria" and known to the Arab doctors were Gessios of Petra and Palladios. The Roman physician Alexander von Tralleis (6th century) is quoted by Rhazes to support his criticism of Galen. The works of Aëtios of Amida only became known in Islamic medicine at a later time; they are not cited by either Rhazes or Ibn an-Nadīm and are first mentioned by al-Biruni in the Kitab as-Saidana, translated by Ibn al-Hammar im 10th century.

One of the first books to be translated from the Greek original into Syrian, and then into Arabic by Māsarĝawai al-Basrĩ at the time of the fourth Umayyad caliph Marwan I , was the medical compendium Kunnāš from Ahron from the 6th century. Later Hunain ibn Ishāq also made a translation.

The doctor Paulus of Aegina lived in Alexandria at the time of the Arab conquest. His works seem to have been used as one of the most important sources by the early Arab physicians and were widely cited from Rhazes to Avicenna. With Paulos, Arabic medicine gains direct connection to the late Hellenistic era.

Hippocrates translations

The partly legendary life story of Hippocrates of Kos was also known to the early Islamic doctors, as was the fact that there were several doctors with this name: Ibn an-Nadīm narrates a short treatise by Thabit ibn Qurra (836-901) on "al-Buqratun "," The Hippocrates ". Even before the translations of Hunain ibn Ishāq, a number of his books must have been available in translations, because around 872 the historian al-Yaʿqūbī compiled a list of works by Hippocrates, to which an overview of the content, quotations or the entire text is often assigned . The names of other early translators have come down to us from the writings of Ibn an-Nadīm. A treatise "at-Tibb al-Buqrati" (The Medicine of Hippocrates) is known by al-Kindī , and his contemporary Hunain ibn Ishāq translated Galen's comments on Hippocrates. The first physician to use the writings of Hippocrates to build his own medical system was Rhazes. At-Tabarī claimed to have better presented the Hippocratic teaching in his work "al-Muʾālaḡāt al-buqrāṭīya". The writings of Hippocrates were quoted and discussed over and over again throughout the following period.

Galen translations

Alongside Aristotle, Galen is one of the most famous ancient scholars. Several of his lost works and details of his own biography are known only from the writings of Arab doctors. Already in Jabir ibn Hayyān's writings, book titles by Galen are repeatedly quoted from early translations of individual works. The historian Al-Yaʾqūbī also cites some works of Galen around 872 AD, the titles of which differ from those chosen by Hunain ibn Ishāq, and are therefore very likely due to earlier translators. In Hunain's comments there are often remarks of the kind that he considered the work of previous translators to be inadequate and that he had re-translated the texts. It is believed that some of Galen's writings were translated as early as the middle of the 8th century, probably from Syriac, perhaps also from Persian.

Hunain ibn Ishāq and his younger contemporary Tabit ben-Qurra are of great importance as translators and commentators in Galen's Arabic medicine. In numerous works they tried to summarize and organize the medical system reproduced in the Galenic writings, and thus to add it to the medical teaching of their time. Beginning with Gabīr in the 8th century, especially clearly in Rhazes' treatise on vision, the criticism of Galen's views begins. Finally, in the 10th century, ʾAli b. al-ʾAbbas al-Maĝūsī:

“As for the great and excellent Galen, he has written numerous works, each of which encompasses only one of the parts of this science. With him, however, there are lengths and repetitions in the list of his statements and evidence [...]. I cannot [...] consider any of his books to be complete. "

Syrian and Persian medicine

Syrian sources

An important source of our knowledge is Ibn Wahshiyya , who transmitted the scriptures of the Nabataeans . We also know the Syrian scholar Sergius von Rešʾainā, who translated numerous writings by Hippocrates and Galen, of which parts 6–8 of a pharmacological work ("περ`ι κράσεως κα`ι δυνάμεως των ῾απλω ναρμάκω ναρμάκω) as well as fragment "Τέχνη ᾽ιατρική" and "περ`ι τροφων δυνάμεων" are received from Galen. Hunain ibn Ishāq improved some of these translations and translated them into Arabic. A preserved, anonymous Syrian work had an influence on the Arabic-writing doctors ʿAlī ibn Sahl Rabban at-Tabarī and Yuhanna ibn Masawaih .

The earliest known translation from Syriac is the Kunnāš (translated from Greek) by the scholar Ahron, translated into Arabic by Māsarĝawai al-Basrĩ in the 7th (1st Islamic) century. Syrian doctors played an important role in the Gundishapur Academy. Their names are known to us through their work at the court of the first Abbasids .

Persian sources

The Academy of Gundischapur plays an important role in imparting Persian medical knowledge. According to Gregorius Bar-Hebraeus, founded by the Sassanid Shapur I in the 3rd century AD, it played an important role in the encounter between Greek and ancient Indian medicine and, through Arabic doctors trained in Gundischapur, also mediated contact with Arabic medicine. The surviving tract Abdāl al-adwiya by the Christian doctor Māsarĝawai (not to be confused with the Jewish doctor and translator M. al-Basrĩ), the first sentence of which reads:

"These are the drugs that have been administered and taught by Greek, Indian, and Persian doctors."

When examining the Firdaus al-Hikma from at-Tabarī , Meyerhof emphasizes that among his technical terms, especially among the disease names, only a few Persian can be found. In contrast, numerous Persian drug names have been adopted into Arabic terminology. Rhazes also seldom relies on Persian terms and only cites the Persian works Kunnāš fārisi and al-Filāha al-fārisiya .

Indian medicine

Indian works on astronomy were already translated into Arabic by Yaqūb ibn Tāriq and Muhammad al-Fazari during the time of the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur . At the latest under Hārūn ar-Raschīd , translations of Indian works on medicine and pharmacology were created. Ibn an-Nadīm gave us the names of three translators in a chapter on Indian medicine: Mankah, Ibn Dahn, and ʾAbdallah ibn ʾAlī. Yuhanna ibn Masawaih quotes an Indian work in his treatise on ophthalmology.

ʿAlī ibn Sahl Rabban at-Tabarī devotes the last 36 chapters of his Firdaus al-Hikmah to Indian medicine and cites works by Sushruta , Charaka and the Ashtanga Hridaya . Rhazes also quotes in al-Hawi and in the Kitab al-Mansuri Sushruta and Charaka along with other authors unknown to him, whose works he only cites as min kitab al-Hind , "an Indian book".

In Max Meyerhof's opinion, Indian medicine has mainly influenced Arabic medicine theory, as many Indian names of plants and drugs occur in Arabic works that are unknown to the Greek tradition. While the Syrians imparted knowledge of Greek medicine, Persian doctors from the school of Gundischapur (which was also partly of Syrian origin) were probably the first mediators between Indian and Arabic medicine.

In the 11th century, al-Biruni , who also wrote a history of India ( Kitab Tarich al-Hind ), wrote in his Kitab as-Ṣaidana (Book of Medicine):

“In the east there is not a single people inclined towards science, except the Indians; but these subjects in particular (that is, medicine) are founded on foundations which are contrary to the rules of the western world to which we are accustomed. In addition, the contrast between us and them in language, religion, customs and habits and their excessive fear of purity and impurity cancel out rapprochement and cut off the handle of mutual conflict. "

Systematic textbooks

"Treasure of the King of Khwarizm" by Ismaʿil al-Jurdschānī

The "Treasure of the King of Khwarizm" ( Daḫirē-ye Ḫārazmšāhī ) is the first systematic medical work in the Persian language and comprises ten books. It covers topics from the fields of physiology, hygiene, diagnosis and prognosis, fever, plague, smallpox and other diseases, special pathology, surgery, dermatology, toxicology and pharmacology or pharmacy. Its author, the Persian doctor Ismaʿil al-Dschurdschānī died in 1136. Another medical work consisting of ten treatises has also come down to us, the "Quintessence of Medicine" ( Zubdat-itibb ).

“Paradise of Wisdom” from at-Tabarī

The first encyclopedic textbook of medicine in Arabic is the "Paradise of Wisdom" ( Firdaus al-Hikmah or Al-Kunnasch ) by ʿAlī ibn Sahl Rabban at-Tabarī , a system of medicine in seven parts written in 860 in Syriac-Arabic and Persian . The book had little influence in the West and was not printed until the 20th century. Mohammed Zubair Siddiqui published the five traditional parts. It is the first work in which pediatrics and child development are described independently, as well as approaches to psychology and psychological therapy. The work shows influences of ancient Indian medicine , as recorded in the works of Sushrutas and Charakas , and of Islamic philosophy. Unlike his contemporaries, at-Tabarī insists that there are strong body-soul connections that the doctor must take into account when treating patients.

"Book of Medicine" by Rhazes

Muhammad ibn Zakarīyā ar-Rāzī ( Latin Rhazes ) wrote his most important work "Treatise on Medicine" in the 9th century. Ar-Razī recorded clinical cases from his personal experience. With his detailed description of the course of smallpox and measles , appendicitis and the eclampsia that occurred during pregnancy , he also gained influence in medical teaching in European culture. Ar-Rāzī also emphasizes the need for mental care for the sick.

"Liber regalis" by Haly Abbas

ʿAli ibn al-ʿAbbas al-Madschūsi ( Latin Haly Abbas ) wrote his “Complete Book of Medical Art” ( Arabic كتاب كامل الصناعة الطبية, DMG Kitāb Kāmil aṣ-Ṣināʿa aṭ-Ṭibbiyya ). He dedicated it to his royal patron Adud ad-Daula , which is why it is also known as “The Royal Book” ( Arabic كتاب الملكي, DMG Kitāb al-Malakiyy , in Europe Latin "Liber regalis" or "Regalis dispositio" ) became known. The Liber regalis is divided into 20 discourses, the first 10 dealing with theory, the other 10 practical topics. This also includes treatises on dietetics and drug theory , approaches to understanding the capillary system and a more precise description of the birth process.

In Europe, parts of the work were translated into Latin by Constantinus Africanus around 1087 . This Liber pantegni was one of the texts on the curriculum at the Schola Medica Salernitana in Salerno . A more complete and accurate translation was made by Stephen of Antioch in 1127, which was widely distributed and was still printed in Venice in 1492 and 1523 .

"Book of Method" by Abulcasis

Abu l-Qasim Chalaf ibn al-Abbas az-Zahrawi ( Latin Abulcasis ) is regarded as the "father of modern surgery ". His 30-volume "Book of (Medical) Method" ( Arabic كتاب التصريف, DMG Kitāb at-Taṣrīf or at-Tasrif ) covers a wide range of medical topics, including a. Dentistry and childbirth . He also wrote about the importance of a positive patient-doctor relationship and also stressed the importance of treating all patients without regard to their social status. He calls for careful observation of individual cases to ensure the best possible diagnosis and treatment.

“At-Tasrif” was translated into Latin by Gerhard von Cremona and illustrated in the 12th century . For about five centuries it was one of the main sources of medieval medical knowledge in Europe and served as a textbook for doctors and surgeons. Abulkasis at-Tasrif describes for the first time the method published later by Theodor Kocher for the treatment of a shoulder dislocation and the "Walcher situation" in obstetrics . The At-Tasrif describes the cauterization and ligation of blood vessels long before Ambroise Paré and was the first book that has come down to us that presented and described various surgical devices and explained the hereditary nature of hemophilia .

Canon of Medicine and Other Works of Avicenna

Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980-1037) was a philosopher of the Hanbali and Muʿtazilist schools and one of the most important doctors, thinkers and researchers in medical history. His medical encyclopedia, the Canon of Medicine ( Arabic القانون في الطب, DMG al-Qānūn fī aṭ-Ṭibb ; Latin Canon medicinae ), written around 1020, was translated into Latin by Gerhard von Cremona in the 12th century . The work, of which 15-30 Latin editions existed throughout the West in 1470 , was considered an important textbook in medicine until the 17th century. In 1493 it was published in a Hebrew version in Naples, and in 1593 it was one of the first Persian works to be printed in Arabic in Rome . In 1650 the "canon" was used for the last time at the universities of Leuven and Montpellier .

Avicenna wrote a "Book of the Healing of the Soul," which is actually more of a fuller treatise on science and philosophy, and 15 other medical works, eight of which are written in verse. Among other things, he described the 25 signs of recognizing diseases , hygienic rules, a detailed materia medica as well as rules for testing the effectiveness of medicines and anatomical notes. He discovered the contagious nature of some diseases such as tuberculosis and introduced the quarantine method to protect the healthy from infection.

"Book of Medicines" by al-Biruni

The “Book of Medicines” ( Kitab as-Ṣaidana ) by al-Biruni is a comprehensive medical encyclopedia that sought a synthesis between Islamic and ancient Indian medicine . In this work, Siamese twins are also described for the first time .

“Complete Works of Medicine” by Ibn an-Nafis

Ibn an-Nafīs (1213-1288) wrote his "Complete Works of Medicine" ( As-Shâmil fî at-Tibb ) in the 13th century. By his death in 1288 he had completed 30 volumes, only a small part of which has survived. In Islamic medicine, the work replaced the “canon” of Avicenna; Arab biographers of the 13th century considered it a “second Avicenna” or even gave it a higher rank. From today's perspective, Ibn an-Nafi's greatest scientific achievement is the theoretical explanation of the pulmonary circulation .

"Surgery of the Empire" by Sabuncuoğlu Şerefeddin

The last encyclopedia to appear in medieval Islamic medicine, and at the same time the first illustrated textbook written in Ottoman-Turkish language , was “Surgery of the Empire ” ( Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye ) by Sabuncuoğlu Şerefeddin , written in 1465. Three original handwritten manuscripts have survived , two of them are attributed to Sabuncuoğlu himself. One is in the Fatah Millet library in Istanbul , one in the Capa Medical History Department of the University of Istanbul , and the third is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

The "surgery of the empire" was based essentially on the Kitāb at-Taṣrīf of Abulcasis. From today's perspective, the probable knowledge of pneumothorax and its treatment is an independent scientific achievement . Sabuncuoğlu also describes the ligature of the temporal artery for the treatment of migraines . In the sections on neurosurgery , women are also shown as surgeons for the first time.

Presentation of the structure and function of the human body

The ancient tradition according to Galen of Pergamon

Two different traditions were handed down from ancient medicine, which Galenus of Pergamon in the 2nd century combined to form a coherent conceptual system of the structure and function of the human body and the cause of its diseases.

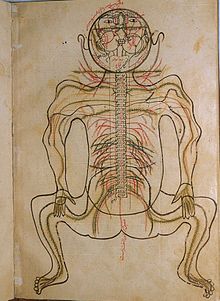

- The "dogmatic" tradition, which is based on the anatomical school of Alexandria in the 3rd century BC, deals with the structure of the human body and the development of disease as a result of anatomical changes in organs. Goes back. The doctors Herophilos of Chalcedon and Erasistratos were possibly the first to ever dissect a person. The anatomical school of Alexandria developed its own pictorial tradition of anatomical depiction: the human body is shown lying frontally on its back with legs spread and bent at the sides, hands resting on the thighs. This pictorial tradition is adopted by the doctors of the Islamic world.

- The “empirical” tradition, founded by Hippocrates (around 400 BC), derived disease from the analysis of symptoms. The diagnosis was not made on the basis of anatomical observations, but understood against the background of humoral pathology , according to which balance of the four juices means health, imbalance means disease.

It was not customary, and for religious reasons forbidden in all societies of the medieval world, to dissect human bodies in order to obtain an accurate knowledge of human anatomy . The idea of the structure of the human body therefore traditionally followed the authority of Galenus of Pergamon, who had transferred the results of his sections from animals to humans. His work was translated into Syrian and Arabic by Hunain ibn Ishāq (808–873) in the 9th century, and in the 10th century Rhazes created a detailed translation of Galen's complete works.

Further development: Rhazes and Ibn an-Nafis

As early as the 10th century, individual doctors expressed doubts about Galen's theories. Through his own empirical experiments, Muhammad ibn Zakarīyā ar-Rāzī, also known by his Latin name Rhazes, came to the opinion that some of Galen's theories could not be correct. Alchemical experiments, published in the book of the secret of secrets ( Kitāb Sirr al-asrār ), also led him to doubt the Aristotelian doctrine of the four elements and thus the foundations of medicine of his time. The 1260-1288 to practicing in Cairo chief physician of the hospital Nassiri, the polymath Ibn al-Nafis studied (1210 / 13-1288), and the first to describe "what the section proves" to the last detail, the pulmonary circulation . He could also have understood the function of the coronary arteries.

Empirical research: Avicenna, Alhazen, Avenzoar

One of the most important contributions Avicennas (Ibn Sina) to the medical science of his time is, in addition to the systematization of knowledge, above all the introduction of systematic empirical research by means of experiments and precise measurement in his main work, the Qānūn at-Tibb ( canon of medicine ). Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan ibn al-Haiṯam (Alhazen) first correctly described the anatomy and physiology of vision in his " Treasure of Optics " ( Kitāb al-Manāzir ) in 1021 .

Abū Merwān 'Abdal-Malik ibn Zuhr (lat. Avenzoar, 1091–1161) was among the first doctors to perform anatomical sections (to study the anatomy of the healthy) and autopsies to determine the causes of illness and death on the bodies of the deceased. His famous "Book of Simplification / Preparation of Therapy and Diet" ( Kitāb at-Taisīr fī l-mudāwāt wa-t-tadbīr ) had a great influence on surgery. He was able to prove that the scabies is caused by parasites . Logically, the correct treatment was to fight the parasite, rather than rebalancing the juices. Ibn Zuhr tried surgical procedures in animal experiments before using them on humans.

In the 12th century, Saladin's personal physicians , al-Shayzari and Ibn Jumay, also performed anatomical dissections. During a famine in Egypt in 1200, Abd-el-latif examined human skeletons and found that Galen was wrong about the formation of the bones of the lower jaw and sacrum .

The first known color-illustrated anatomical atlas of Islamic medicine, "The structure of the human body" in Arabic تشريح بدن انسان, DMG Tashrīḥ-i badan-i insān , also known as the "Anatomy of Mansur", was created in the 14th century by the Persian doctor Mansur ibn Ilyas .

Structure and function of individual organs

blood circulation

The fact that blood moves through the body was already known to the ancient Greek anatomists, but not how the blood gets from the right to the left ventricle and into the body. According to Galen , the blood flowed through an invisible opening in the heart septum. Ibn an-Nafis realized that this assumption must be wrong. He knew from dissections that the cardiac septum was impermeable and concluded from this that blood had to flow from the right ventricle into the lungs. Thus an-Nafīs had described the pulmonary circulation for the first time.

Older authors assumed that an-Nafīs' findings had remained unknown in the West until the 20th century and that the circulatory system was independently rediscovered by William Harvey in 1616. The description of the pulmonary circulation by Michael Servetus in the fifth book of his work Christianismi Restitutio (1553) was traced back by some historians to the knowledge of the work of Ibn an-Nafīs: In the library of the Escorial there are still four Arabic manuscripts of the commentary on the "Canon" of Ibn Sīnā ( Arabic شَرح تَشريح القانُون, DMG Šarḥ tashrîḥ al-qānūn ; approx. 1242) received. In 1546 Andrea Alpago had translated parts of the "Canon" into Latin. This translation is still available in the library of the Escorial, so Servetus should have known the work. The commentary on the fifth book of the "Canon", translated under the title Ebenefis philosophi ac medici expositio super quintum canonem Avicennae ad Andrea Alpago Bellunensi , does not contain any references to the blood circulation. The commentary on Book Six shows only a few inconsistencies in Galen's concept in Alpago's translation. An independent discovery of pulmonary circulation by both scholars is therefore still considered possible.

eye

The ancient Greek doctors suspected that the human eye emits "rays of vision" which, like a lamp, scanned the environment and thus created the sensory impression, similar to a blind person who scans his surroundings with a stick. Aristotle, on the other hand, was of the opinion that light existed independently of the human eye and that it paves its way from objects to the eye via a medium. Alhazen examined the structure of the eye and realized that the eye lens functions exactly like an optical lens according to the laws of light refraction, which he had described in his work " Treasure of Optics " ( Kitāb al-Manāzir ).

stomach

Ahmad ibn Abi l-Aschʿath, a doctor from Mosul in Iraq, described the function of the stomach using an animal experiment on a living lion in his work al-Qadi wa-l-muqtadi . He wrote:

“When food enters the stomach, especially when it is abundant, the stomach expands and its wall layers expand. […] The audience said the stomach was rather small, so I continued to pour pitcher after pitcher into his throat. […] The inner layer of the stretched stomach became as tender as the outer layer of the peritoneum. I cut open the stomach and the water leaked out. The stomach shrank and I could see the doorman's muscle. "

This description preceded that of William Beaumont by nearly 900 years.

Anatomy of the lower jaw

Galenus wrote in his work De ossibus ad tirones that the lower jaw consists of two bones, which can be seen if it falls apart in the middle while cooking. Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi had the opportunity to examine the remains of starving people during a famine in Cairo in 1200. In his book Al-Ifada w-al-Itibar fi al-Umar al Mushahadah w-al-Hawadith al-Muayanah bi Ard Misr (Book of Instruction and Admonition on Things Seen and Recorded Events in the Land of Egypt), he writes:

“All anatomists agree that the bone of the lower jaw consists of two parts that are connected at the chin. […] The observation of this part of the body convinced me that the lower jaw bone is a single one, without a joint or seam. I have repeated this observation many times, on more than two hundred heads. […] I was supported by various other people who repeated the same examination, both in my absence and under my eyes, and, like me, they never saw anything other than a single bone, as I said. "

Al-Baghdadi's discovery, however, remained largely unknown, perhaps because he had published it in a book that mainly deals with the geography, botany and monuments of Egypt, as well as a detailed description of the famine and its consequences. Al-Baghdadi probably did not carry out his original plan to publish his anatomical observations in his own book.

pharmacology

Pharmacology , the science of medicines as an independent science, was established by Islamic doctors in the 9th century. Al-Biruni notes:

"Pharmaceutical science differs from medicine as language and sentence structure differ from linguistic elaboration, sentence rhythm from poetry, and logic from philosophy, because it is more of a helpful partner for medicine than a slave."

Sabur (d. 869) wrote the first pharmacology textbook.

Testing the effectiveness of a drug

In his canon of medicine, Avicenna defined precise rules as to how a medicinal product should be designed in terms of its tolerability and effectiveness. Some comparable rules still apply today to clinical pharmacology and modern drug testing :

- The drug must be pure and not contain incidental impurities.

- It should only be used to treat a disease and not a disease syndrome.

- The drug has to prove its effectiveness in two different diseases, because sometimes a drug is actually effective, sometimes the cure was only due to chance.

- The quality of the drug must match the severity of the disease. For example, some medicines cause heat while illness is characterized by cold, so the remedy is ineffective.

- The time until the effect occurs must be carefully observed so as not to confuse a real effectiveness with a coincidence.

- The effectiveness of a drug must be reliable and set in different cases of illness, otherwise one would have to expect a random effect.

- The effectiveness test must be carried out on humans, because if you try drugs on lions or horses, you cannot draw any conclusions about the effects on humans.

Pain therapy

Medieval Islamic doctors knew and used the pain relieving effects of opium poppy and cannabis . Cannabis was only introduced from India in the 9th century. The Greco-Roman doctor Pedanios Dioskurides recommended the use of cannabis seeds in obstetrics , and cannabis juice for earache in the 1st century . Opium poppy is of Yuhanna ibn Masawaih for the treatment of pain associated with colic of the gallbladder , fever , indigestion, eye, headache, toothache, pleurisy , and as a sleep aid . Al-Tabari also stated that an opium poppy extract could be deadly and that opium poppy extracts and opium should be considered poisons.

Hospitals and training centers

Special places and buildings for the care and treatment of sick people by specially trained people are known from ancient times, as are medical schools such as that of Kos , where Hippocrates of Kos also worked. In the Persian Empire , the Academy of Gundischapur was founded as early as the Sassanid period , in which theoretical and practical training took place.

Bimaristan and Darüşşifa

In the Islamic culture, hospitals ( Persian بیمارستان, DMG Bimaristan , 'hospital, madhouse', Turkish Darüşşifa or also Şifahane), which initially served to isolate people with infectious or psychiatric diseases. Later the bimaristans functioned like public hospitals and research institutions, and also trained students.

Bimārestāns were secular institutions and treated the sick regardless of their origin or religion. Often, hospitals were built as part of a complex of buildings around a mosque, which also included a school ( madrasa ), library, pharmacy and kitchen. The institution was mostly financed by a religious foundation ( Waqf ). The statutes of such foundations often stipulate that nobody should and should not be turned away until health has been completely restored. Men and women were treated in separate but equally equipped departments. Depending on the size of the Bimaristan, separate departments for mental, infectious and eye diseases, surgical and non-surgical cases could be set up.

Training of doctors

The hospital was not just the place where the sick were treated. It also served as a medical school and trained doctors. The training was acquired by private teachers, through own studies and in lectures. The Islamic hospitals were the first to keep accurate records of patients and their treatments. Most of the time, the students were responsible for keeping the medical records, which were collected by trained doctors and used as the basis for treating other patients.

At the latest by the time of the Abbasids , formal approval was a prerequisite for practicing the medical profession. In 931, Caliph al-Muqtadir became aware of the death of a sick person due to medical malpractice. He then ordered Sinan ibn Thabit to examine the doctors. Nobody should be allowed to treat sick people without passing the exam.

See also

literature

- Fuat Sezgin : History of Arabic Literature. Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine. EJ Brill Verlag, Leiden 1970.

- Donald Campbell: Arabian medicine and its influence on the Middle Ages, I – II. London 1926, reprinted Amsterdam 1974.

- Wolfgang U. Eckart: History of medicine. Springer-Verlag 1998, 3rd edition, ISBN 3-540-63756-7 , pp. 101-103.

- Sami Hamarneh: Bibliography on medicine and pharmacy in medieval Islam. Stuttgart 1964 (= publications of the International Society for the History of Pharmacy. New series, 25).

- Danielle Jacquart, Françoise Micheau: La médicine arabe et l'occident médiéval. (= Collection Islam-Occident. Volume 7). Paris 1990.

- Kay Peter Jankrift: Illness and Medicine in the Middle Ages. Darmstadt 2003.

- Heinz Schott (Ed.): Milestones in Medicine. Harenberg, Dortmund 1996, ISBN 3-611-00536-3 .

- Edward G. Browne: Islamic Medicine . Goodword Books, New Delhi 2002, ISBN 81-87570-19-9 .

- Michael W. Dols: Medieval Islamic Medicine: Ibn Ridwan's Treatise "On the Prevention of Bodily Ills in Egypt", in: Comparative Studies of Health Systems and Medical Care . University of California Press, 1984, ISBN 0-520-04836-9 .

- Hans Hugo Lauer: Ethics and medical thinking in the Arab Middle Ages. In: Eduard Seidler , Heinz Schott (ed.): Building blocks for the history of medicine. Heinrich Schipperges on his 65th birthday. Stuttgart 1984 (= Sudhoffs Archiv , supplement 24), pp. 72-86.

- Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed: Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 .

- Peter E. Pormann, Emilie Savage-Smith: Medieval Islamic Medicine . Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2007, ISBN 978-0-7486-2066-1 .

- Roy Porter: The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2001, ISBN 0-521-00252-4 .

- Jean-Charles Sournia: The Arabic Medicine. In: Illustrated History of Medicine. German adaptation by Richard Toellner et al., Special edition in six volumes, 1986, Volume II, pp. 584–625.

- Otto Spies : Contributions to the history of Arab dentistry. In: Sudhoff's archive. Volume 46, 1962, pp. 153-177.

- Manfred Ullmann : Medicine in Islam. (= Handbook of Oriental Studies , 1st section, supplementary volume VI, 1). Leiden and Cologne 1970.

- Manfred Ullmann: Islamic Medicine . In: Islamic Surveys . tape 11 , 1978, ISBN 0-85224-325-1 .

- Ursula Weisser : Ibn Sina and the medicine of the Arab-Islamic Middle Ages - old and new judgments and prejudices. In: Medical History Journal. Volume 18, 1983, pp. 283-305.

- Ursula Weisser: Conception, Heredity and Prenatal Development in Medicine of the Arab-Islamic Middle Ages. Erlangen 1983.

- Literature by Gerrit Bos , Medieval Jewish-Islamic science (Medicine); medieval Arabic-Hebrew medical terminology, Academia

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Dietrich Brandenburg: Priest doctors and healing arts in ancient Persia. J. Fink Verlag, Stuttgart 1969; cited here: Special edition under the title The Doctor in the Old Persian Culture. Robugen, Esslingen 1969, p. 104.

- ↑ Eckart: History of Medicine. 1998, pp. 101-103.

- ↑ Sami Harmaneh: Arabic medicine and its impact on teaching and practice of the healing arts in the West. In: Oriente e Occidente nel Medioevo: Filosofia e Scienze. Rome 1971 (= Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Fondazione Alessandro Volta. Atti dei Convegni 13: Convegno Internationale 9-15 April 1969. ) pp. 395-429.

- ↑ Danielle Jacquart, Françoise Micheau: La médicine arabe et l'occident médiéval. 1990.

- ↑ Jorit Wintjes : Introduction. In: Konrad Goehl : Avicenna and its presentation of the medicinal effects. 2014, pp. 5–27, here: p. 19.

- ^ Gotthard Strohmaier : Avicenna. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-41946-1 , pp. 109 and 135-139.

- ↑ Danielle Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West . In: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 963-84 .

- ↑ Jorit Wintjes: Introduction. 2014, p. 19.

- ↑ Eckart: History of Medicine. 1998, p. 103.

- ^ Richard Colgan: Advice to the Healer: On the Art of Caring . Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2013, ISBN 978-1-4614-5169-3 .

- ^ Friedrun R. Hau: Arabic medicine in the Middle Ages. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 87-90; here: p. 87 f. ( Sources of Arabic medicine ).

- ↑ Ibn Chaldūn: The Muqaddima. Reflections on world history . CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62237-3 , p. 391-395 .

- ↑ a b c d Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 3-4 . in google books

- ↑ a b Fuad Sezgin: History of Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 203-204 .

- ↑ BĪMĀRESTĀN, entry in Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Fuad Sezgin: History of the Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 5 .

- ↑ a b Fuad Sezgin: History of Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 8-9 .

- ↑ a b c Fuad Sezgin: History of Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 20-171 .

- ↑ See on this: M. Meyerhof: Joannes Grammatikos (Philoponos) of Alexandria and the Arabic medicine. Communications from the German Institute for Egyptian Antiquity in Cairo, Vol. II, I, 1931, 1–21

- ↑ Friedrun Hau: Thabit ibn Qurra. In: Werner E. Gerabek u. a. (Ed.): Encyclopedia of medical history. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1377.

- ^ Fuad Sezgin: History of the Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 23-47 and 260-263 .

- ^ E. Meyerhof: Autobiographical fragments of Galen from Arabic sources. In: Archives for the History of Medicine. 22, 1929, pp. 72-86.

- ^ Fuad Sezgin: History of the Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 68-140 .

- ^ Fuad Sezgin: History of the Arabic literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 76-77 .

- ↑ Max Meyerhof: ʿAlī ibn Rabban at-Tabarī, a Persian doctor of the 9th century AD. Journal of the German Oriental Society 85 (1931), pp. 62–63

- ↑ a b Fuat Sezgin: Syrian and Persian sources. In: History of Arabic Literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 172-186 .

- ↑ Fuat Sezgin: Syrian and Persian sources. In: History of Arabic Literature . Volume III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary Medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 175 .

- ^ Max Meyerhof: On the transmission of greek and indian science to the arabs. In: Islamic Culture. 11, 1937, p. 22.

- ↑ G. Flügel: On the question about the oldest translations of Indian and Persian medical works into Arabic. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society. 11, 1857, pp. 148-153, cited in Sezgin, 1970, p. 187.

- ↑ A. Müller: Arabic sources for the history of Indian medicine. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society. 34, 1880, pp. 465-556.

- ↑ a b Fuad Sezgin: Syrian and Persian sources. In: History of Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine - Pharmacy - Zoology - Veterinary medicine . EJ Brill, Leiden 1970, p. 187-202 .

- ^ Max Meyerhof: On the transmission of greek and indian science to the arabs. In: Islamic Culture. 11, 1937, p. 27.

- ↑ Max Meyerhof: The foreword to Beruni's drug studies. Source. u. Stud. Business d. Nat. scientific u. Med. (3) 1933, p. 195, quoted from Sezgin 1970, p. 193.

- ↑ I. Afshar, MT Danis-Pašuh (ed.): Daḫirē-ye Hārazmšāhē. Tehran 1965.

- ^ Friedrun R. Hau: al-Ğurğānī, Ismaʿil. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 518.

- ↑ Amber Haque: Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists. In: Journal of Religion and Health 43, No. 4, 2004, pp. 357–377 [361]

- ↑ Charles SF Burnett, Danielle Jacquart (ed.): Constantine the African and ' Alī Ibn Al ' Abbās al-Magusi: The Pantegni and Related Texts . Brill, Leiden 1995, ISBN 90-04-10014-8 .

- ^ A b Danielle Jacquard: Islamic Pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Theories and Substances. European Review 16 (2008), pp. 219-27

- ↑ a b Walter J. Daly, D. Craig Brater: Medieval contributions to the search for truth in clinical medicine. In: Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 43, No. 4, 2000, pp. 530-540.

- ↑ Hans Hinrich Biesterfeldt: Ibn al-Nafis, . In: Josef W. Meri (Ed.): Medieval Islamic Civilization . tape 1 . Taylor & Francis / Routledge, New York 2006, pp. 347-349 .

- ↑ Kaya SO, Karatepe M, Tok T, Onem G, Dursunoglu N, Goksin, I: Were pneumothorax and its management known in 15th-century anatolia? . In: Texas Heart Institute Journal . 36, No. 2, September 2009, pp. 152-153. PMID 19436812 . PMC 2676596 (free full text).

- ↑ G. Bademci (2006), First illustrations of female "Neurosurgeons" in the 15th century by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu, Neurocirugía 17 : 162-165.

- ↑ Robert Herrlinger: History of the anatomical illustration . tape 1 : From antiquity to 1600 . Moss, 1967.

- ^ Toby Huff: The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West . Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-52994-8 , pp. 169 .

- ^ E. Savage-Smith: Attitudes Toward Dissection in Medieval Islam . In: Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences . 50, No. 1, Jan. 1, 1995, pp. 67-110. doi : 10.1093 / jhmas / 50.1.67 . PMID 7876530 .

- ↑ Julius Ruska : Al-Razi's book Secret of the Secrets. With introduction and explanations in German translation. ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Springer, Berlin 1937 (= sources and studies on the history of natural sciences and medicine, Volume VI)

- ↑ Sigrid Hunke: Allah's Sun over the Occident: Our Arab Heritage . 6th edition. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN 3-596-15088-4 .

- ↑ Cristina Álvarez Millán: Ibn Zuhr. In: Thomas F. Glick u. a. (Ed.): Medieval science, technology, and medicine: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis, New York 2005, pp. 259–261, here 259 ( available from Google Books ).

- ^ Rabie E. Abdel-Halim (2006): Contributions of Muhadhdhab Al-Deen Al-Baghdadi to the progress of medicine and urology. In: Saudi Medical Journal. 27 (11): pp. 1631-1641.

- ^ Rabie E. Abdel-Halim: Contributions of Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) to the progress of surgery: A study and translations from his book Al-Taisir. In: Saudi Medical Journal. 26/9 (2005), pp. 1333-1339.

- ↑ Emilie Savage-Smith: Medicine. In: Roshdi Rashed (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Volume 3, pp. 903-962 (951-952). Routledge, London / New York 1996.

- ^ Andrew J. Newman: Tashrīḥ-i Manṣūr-i: Human Anatomy between the Galen and Prophetical Medical Traditions. In: La science dans le monde iranien à l'époque islamique . Institut Français de Recherche en Iran, Tehran 1998, p. 253-271 .

- ↑ Sami I Haddad, Amin A. Khairallah: A forgotten chapter in the history of the circulation of the blood . In: Annals of Surgery . 104, July 1936, pp. 1-8. PMC 1390327 (free full text).

- ↑ Ms. 826, fols. 218-247; Ms. 828, 130 fols. (from the 16th century); Ms. 029, 65 fols .; Ms. 832; after José Barón Fernández: Ibn an-Nafis y la circulación de la sangre. Medicina & Historia 4, July 1971, pp. II-XVI. Full text (PDF) , accessed on October 10, 2017.

- ↑ CD O'Malley: A latin translation of Ibn Nafis (1547) related to the problem of the circulation of the blood . In: Jour. Hist. Med., Vol. XII . 1957, p. 248-253 .

- ↑ John B. West: Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age . In: Journal of Applied Physiology . 105, 1985, pp. 1877-1880. PMC 2612469 (free full text).

- ↑ Farid S. Haddad: InterventionaI Physiology on the Stomach of a Live Lion: Ahmad ibn Abi ai-Ash'ath (959 AD) . In: Journal of the Islamic Medical Association . 39, March 18, 2007, p. 35. doi : 10.5915 / 39-1-5269 . Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ A b Antoine de Sacy: Relation de l'Égypte, par Abd-Allatif, médecin Arabe de Baghdad . L'Imprimerie Impériale, 1810 ( full text in Google book search).

- ^ Charles Donald O'Malley: The History of Medical Education: An International Symposium Held February 5-9, 1968 , Volume 673. University of California Press, Berkeley, Univ. of Calif. Press 1970, ISBN 0-520-01578-9 , pp. 60-61.

- ↑ a b c d e Sami Hamarneh: Pharmacy in medieval islam and the history of drug addiction . In: Medical History . 16, No. 3, July 1972, pp. 226-237. doi : 10.1017 / s0025727300017725 . PMID 4595520 . PMC 1034978 (free full text).

- ↑ Andrew Forbes, Daniel Henley, David Henley (2013). Pedanius Dioscorides. In: Health and Well Being: A Medieval Guide. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books, 1953.

- ↑ Indalecio Lozano PhD: The therapeutic use of Cannabis sativa (L.) in Arabic medicine. In: Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics 1, 2001, pp. 63-70.

- ↑ Peregrine Horde: The Earliest Hospitals in Byzantium, Western Europe, and Islam . In: Journal of Interdisciplinary History . 35, No. 3, Winter 2005, pp. 361-389. doi : 10.1162 / 0022195052564243 .

- ^ Françoise Micheau: The Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East, in: Régis Morelon, Roshdi Rashed, Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-12410-7 , pp. 991-992 .

- ^ A b c Nigel J. Shanks: Arabian medicine in the Middle Ages . In: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine . 77, No. 1, January 1984, pp. 60-65. PMID 6366229 . PMC 1439563 (free full text).

- ↑ a b c Haji Hasbullah Haji Abdul Rahman: The development of the Health Sciences and Related Institutions During the First Six Centuries of Islam . In: ISoIT . 2004, pp. 973-984.

- ^ A b c d Andrew C. Miller: Jundi-Shapur, bimaristans, and the rise of academic medical centers Archived from the original on December 29, 2015. In: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine . 99, 2006, pp. 615-617. doi : 10.1258 / jrsm.99.12.615 . Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ↑ a b Hussain Nagamia: Islamic Medicine History and Current Practice . In: Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine . 2, No. 4, October 2003, pp. 19-30. Retrieved December 29, 2015.