Obstetrics

As obstetrics , even Tokologie or obstetrics called, refers to the subject area of medicine that deals with the monitoring of pregnancies as well as the preparation, implementation and follow-up treatment of births and any necessary operations involved in connection therewith. This also includes the work of midwives and obstetricians. It is a branch of gynecology .

History of Obstetrics

Antiquity

Obstetrics by other women in antiquity has already been handed down in cabaret. Terracotta figurines with obstetrical scenes may have served to ask the gods responsible for assistance or to calm the pregnant women. Papyri (such as the so-called Papyrus Kahun ) document not only gynecological but also obstetric medicine for ancient Egypt . Obstetrics ( Maieutik ) was considered part of the medical art in antiquity and was practiced primarily by doctors and midwives, which are often not strictly differentiated from them.

middle age

Up until modern times, practical obstetrics was a purely women's domain, with men dealing with the topic in theoretical writings, including Hippocrates . Meyers Konversationslexikon (1889) judged the medieval help for labor:

“In the Christian West, obstetrics was only in the hands of untrained women or, at most, male bunglers. In difficult cases they were often content with calling clergymen to give birth who tried to provide help through superstitious means. "

However, this view is only partially correct. As early as the 12th century, the Trotula Ensemble was a detailed work on various aspects of gynecology, including obstetrics and baby care . The main work Trotula major was written by a doctor from the school in Salerno . It was widely distributed throughout Europe in the late Middle Ages and was regarded as a standard work until the early modern period. Around 200 manuscripts, including numerous translations into national languages, are still preserved today.

One of the first midwifery ordinances, as it can be documented more frequently in the 16th century, was issued in 1480 by Bishop Rudolf von Scherenberg, who ruled the Hochstift Würzburg (midwives in Würzburg had to take an oath as early as 1432 ).

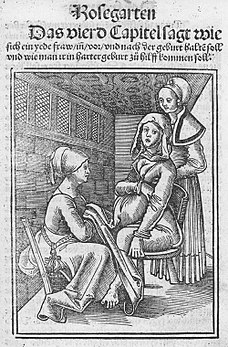

In 1513 a textbook for midwives was published with the title Der swangern Frawen and Midwives Rosengarten . It describes the child's head position as the best birth position - which was nothing new - and the second best position is the position of the feet.

Modern times

Obstetrics with a medical orientation began to take shape in the 16th century. Male obstetricians were still a rarity at the time. It was unusual for King Louis XIV to call in a surgeon from Arles during the delivery of his mistress, Louise de La Vallière , who was then officially appointed as the court's obstetrician. In Germany, obstetrics remained the domain of midwives who received no formal training and passed on their knowledge orally. There were also some specialist books. Meyers Konversationslexikon (1889) described the work Neues Midammenlicht (1701) by the Dutchman Hendrik van Deventer (1651–1724) as the first scientific work on the subject and noted that the latter "also sought to reduce the use of the murderous instruments used to dismember the child" .

In the 18th century the forceps were invented, which, like the other instruments, were generally only allowed to be used by doctors. At the German universities, following French and English developments, obstetric teaching of “midwifery” was established as an independent subject in the 18th century. In 1741 Philipp Adolph Böhmer offered courses in obstetrics at the Medical Faculty of the University of Halle . The Irish obstetrician Fielding Ould (1710–1789) wrote an important textbook on obstetrics in 1742 and is considered to be a co-founder of the theory of birth mechanics . The first births were induced artificially in England in the middle of the 18th century. The method of cesarean section was already known in antiquity, but up until modern times a caesarean section was only carried out in life-threatening emergencies, so often on mothers who had just died, in order to save the child by caesarean section.

One of the most common measures for complications during childbirth used to be the so-called turning , in which the midwife or doctor tried to turn the child in the womb so that it can pass the birth canal in a favorable position. In the 19th century, the woman giving birth could receive anesthesia with chloroform ; this made an initially physiological birth difficult, if not impossible. Therefore, the forceps (Forzeps) were often used, a caesarean section could only be carried out by specialized surgeons. But sometimes it was no longer possible to help the child. From Meyer's Konversationslexikon :

“The worst is the position of the face, which, if the obstetrician is there in time, can be transformed into a skull or by turning it into a foot position. If, on the other hand, the child's head is already wedged into the pelvis, nothing remains but to pierce (perforation) or break it (cranioclasis) and then use the forceps to end the birth. By law, the midwife is only entitled to perform the phrase if medical help cannot be reached within the necessary period. Applying the forceps or even killing the child through perforation is only permitted to the doctor. "

Up until the 20th century, most of the births were home births with a midwife providing obstetrics.

In the 18th century the first maternity houses and educational institutions ( building centers , accouchier houses ) for midwives and obstetricians were set up. In Strasbourg there was the first maternity hospital in 1728, in London in 1739. In Germany the first midwifery school in 1751 was at the Berlin Charité ; that year there was also the first birthing center in Göttingen. At the beginning of the 19th century, a dispute arose among doctors about whether natural delivery or forceps delivery had more advantages. The importance of hygiene was so in the maternity homes initially more mothers still unknown at this time childbirth on puerperal fever killed than in home births. Only the obligation of the medical staff to wash their hands before and after contact, as well as the disinfectant carbol , led to a significant decrease in the number of infections.

In 1853 the anesthetist John Snow used chloroform anesthesia for the first time in obstetrics when Queen Victoria gave birth to her son Leopold. Dozens of soporific drugs were also used to relieve pain in childbirth and anesthetics were injected under the skin, into the veins, into the muscles or near the spinal cord. The technique of pain relieving anesthesia has been increasingly perfected.

20th century

In the course of the 20th century, the majority of births shifted to the clinics .

The Reich Midwives Act of 1938, on the other hand, enacted state recognition of midwives in Germany and gave preference to home delivery . Midwives as well as pediatricians and maternity wards in the clinics were obliged to observe the families and to report malformations and diseases of newborn children.

The English doctor Grantly Dick-Read also turned against the trend and warned since the 1930s that no anesthetic is completely safe for mother and child, since narcotics “are, to a certain extent, poisons”. With it began after the Second World War in some places, against the bitter resistance of the medical profession, a “more soul in obstetrics”, which is no longer considered a branch of surgery today.

Nevertheless, the number of home births in Germany has been falling continuously since the 1950s. One of the main reasons for this was that, since 1968, the health insurances have covered the costs of a clinical birth. From the 1970s onwards, home births supervised by midwives became more and more rare in Germany.

Caesarean section (Caesarean section)

By 2012, the increase in clinical deliveries in some industrialized countries also led to a sharp increase in the number of caesarean sections . In 2010 there were 209,441 caesarean sections in Germany, which corresponds to almost 32 percent of all 656,390 deliveries in hospitals. In contrast, in 2000 there were 160,183 caesarean sections out of a total of 746,625 deliveries, or 21.5 percent, in 1995 only 131,921 caesarean sections deliveries, which was less than 18 percent; In 1991 the proportion was only 15.3 percent. In the decade between 2000 and 2010, the number of all births fell by over 12 percent, while at the same time the absolute number of caesarean sections rose by almost 31 percent. Their share has more than doubled within two decades, from around a seventh to almost a third.

There are clear regional differences. In Saxony, for example, only about one in five children is born by caesarean section, whereas in North Rhine-Westphalia it is more than one in three. Within North Rhine-Westphalia, on the other hand, the Caesarean section rate in Aachen was 36% around 2010, while it was only between 22 and 23% in Mönchengladbach, in the Rhine district of Neuss and in the district of Euskirchen. New study results determine that in 2010 the rate of Caesarean sections in the districts and independent cities in Germany varied between 17% in Dresden and 51% in Landau in the Palatinate - that is, three times as much.

In Austria in 2012 almost every third baby was born by caesarean section (31.5 percent), twice as often as 15 years earlier. In some maternity clinics, the rate of caesarean sections was over 50 percent. The International Association of Gynecology and Obstetrics ( FIGO ) was critical of this development.

"At present, due to the fact that there are no clear advantages, performing a caesarean section is not ethically justified for non-medical reasons."

Critics of the increasing tendency to caesarean sections - especially when it comes to "unplanned" sections (secondary sections) - suspect a significant incentive to do so from the remuneration practice of the amended law in Germany, because the clinics have a disproportionate economic advantage over conventional births and even more compared to "planned" (primary) caesarean sections.

Obstetrics personalities

- Soranos of Ephesus , around 100 AD, Greek doctor in Rome, author of the first midwifery textbook on gynecology

- Abulcasis (936-1013), Andalusian doctor and scientist who dealt in particular with surgery, but also with gynecology and obstetrics

- Trota von Salerno , 11th or 12th century, Italian doctor and author of several treatises and works, e. B. Passionibus Mulierum Curandorum

- Eucharius Rösslin the Elder , 1470–1526, German doctor, author of the textbook The Pregnant Women and Midwives Rosegarten

- Louyse Bourgeois , 1563–1636, midwife at the French royal court, pioneer of modern obstetrics and author of a midwifery book

- Justine Siegemundin , 1636–1705, German midwife at the Brandenburg court, published the first textbook for midwives in 1690

- Ignaz Semmelweis , 1818–1865, Hungarian doctor, introduction of hygiene measures in obstetrics

- Carl Braun von Fernwald , 1822–1891, Austrian gynecologist, from 1849 to 1853 as the successor to Ignaz Semmelweis, assistant to Johann Klein at the First Obstetrical University Clinic in Vienna.

- Louise McIlroy (1874–1968), Scottish doctor and gynecologist. First woman to graduate in medicine, first female medicine professor in the UK.

- Carl Joseph Gauß , 1875–1957, German gynecologist and university professor, introduction of twilight sleep in obstetrics

- August Mayer , 1876–1968, German doctor, co-founder of psychosomatic gynecology

- Grantly Dick-Read , 1890–1959, English physician, natural birth advocate

- Fernand Lamaze , 1891–1957, French doctor, childbirth with little pain

- Frédérick Leboyer , 1918–2017, French doctor, gentle birth

- Eva Reich , 1924–2008, Austro-American doctor, work topics a.o. gentle childbirth as well as treatment of so-called cry babies

- Erich Saling , * 1925, German doctor, is considered the father of perinatal medicine

- Michel Odent , * 1930, French doctor and student of Frédérick Leboyer

- Ina May Gaskin , * 1940, American midwife, founder of the "Farm" in Tennessee, author of Spiritual Midwife and Self-Determined Birth

- Ingeborg Stadelmann , * 1956, German midwife and author

- Friederike zu Sayn-Wittgenstein , * 1961, midwife and professor for nursing and midwifery science at the Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences

- Eva Cignacco , * 1961, the first Swiss midwife to receive a doctorate and who helped midwifery science to make its breakthrough in Switzerland

See also

- Accouchierhaus

- Miscarriage , maternal mortality , sudden infant death , prenatal care , stillbirth

- Birth , birthing chair , antenatal

- midwife

- Storage according to Fritsch

- infant

literature

- Lucia Aschauer: giving birth under observation. The establishment of male obstetrics in France (1750–1830). Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2020 (= history and gender. Volume 71), ISBN 978-3-59-350955-6 .

- Heinrich Fasbender: History of obstetrics. Jena 1906; Reprint Hildesheim 1964.

- Edward W. Jenks: The gynecology of antiquity. Edited from English by Ludwig Kleinwächter . In: German archive for the history of medicine and medical geography. Vol. 6, 1883, ZDB -ID 527039-x , pp. 41-55 ( online ) and 251-268 ( online ); Reprint: Olms, Hildesheim / New York 1971.

- G. Klein: Old and New Gynecology. Festival ceremony for Franz von Winckel . Lehmann, Munich 1936. - Contents: Pictorial representation of the female anatomy from the 9th century to Vesal, famous obstetricians of the 16th and 17th centuries, the difference in the length of time at birth for Japanese and European women.

- Britta-Juliane Kruse: Hidden healing arts. History of gynecology in the late Middle Ages. (Phil. Dissertation FU Berlin 1994: Verborgene Heilkünste. Gynecology and obstetrics in manuscripts and prints from the 15th and 16th centuries ), De Gruyter, Berlin and New York 1996 (= sources and research on literary and cultural history , 5; also: Sources and research on the linguistic and cultural history of the Germanic peoples , 239), ISBN 978-3-11-014704-9 .

- André Pecker: Gynecology and obstetrics from ancient times to the beginning of the 18th century. In: Illustrated History of Medicine. German adaptation by Richard Toellner and others, special edition Salzburg 1986, II, pp. 1002-1053.

- Rainer Pöppinghege: Between home birth and hospital. On the history of obstetrics and gynecology. Schmitz and Sons, Wickede 2005.

- Friederike zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (Ed.): Rethinking obstetrics. Report on the situation and future of midwifery in Germany. Hans Huber, Bern 2007, ISBN 978-3-456-84425-1 .

- Friederike zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (Hrsg.): Handbook midwifery delivery room . From the idea to implementation. Midwifery Research Association - University of Applied Sciences Osnabrück - Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences, Osnabrück 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-017371-4 .

- Daniel Schäfer : Obstetrics. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 463 f.

- Heinrich Martius : textbook of obstetrics. 6th edition. Thieme, Stuttgart 1964.

- Margaret Schleissner: Pseudo-Albertus Magnus: 'Secreta mulierum'. A late medieval prose treatise on evolution and birth doctrine and the nature of women. In: Würzburger medical historical reports 9, 1991, pp. 115-124.

- Peter Schneck: Gynecology (modern times). In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 429-435.

- Hans-Christoph Seidel: A new 'culture of giving birth': the medicalization of birth in the 18th and 19th centuries in Germany. (Phil. Dissertation Bielefeld) Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1998 (= Medicine, Society and History , Supplement 11), ISBN 3-515-07075-3 .

Web links

- Marie von Kuck: Violence in obstetrics - "Crying won't help you either!" Deutschlandfunk.de , Das Feature , November 21, 2017

- Internet slide presentation on obstetrics (for medical students) e-learning.studmed.unibe.ch

- Obstetric-Gynecological Collection . University of Greifswald

Individual evidence

- ↑ Felix Reinhard: Gynecology and obstetrics of the ancient Egyptian papyri, II. In: Sudhoffs archive. Volume 10, 1917, pp. 124-161.

- ^ Britta-Juliane Kruse: Gynecology (antiquity and the Middle Ages). In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 423-429, here: p. 423.

- ↑ On medieval obstetrics, see also Rolf M. Kully: Philologie und Obstetrik (on “ Parzival ” 109, 5). In: Amsterdam Contributions to Older German Studies. Volume 16, 1981, pp. 91-97.

- ↑ Monica H. Green: Who / what is “Trotula”? (PDF) 2008.

- ↑ Monica H. Green: Obstetrical and gynecological texts in Middle English. In: Studies in the Age of Chaucer 14, 1992, pp. 53-88.

- ↑ Peter Kolb: The hospital and health system. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2 (I: From the beginnings to the outbreak of the Peasant War. 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1465-4 ; II: From the Peasant War 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria 1814. 2004, ISBN 3 -8062-1477-8 ; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 ), Theiss, Stuttgart 2001–2007, Volume 1, 2001, p 386-409 and 647-653, here: p. 408 f.

- ^ Peter Schneck: Gynecology (modern times). In: Encyclopedia of Medical History. 2005, p. 434.

- ↑ Axel W. Bauer : Ould, Sir Fielding. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1085.

- ↑ Birth is work . In: The mirror . No. 23 , 1955 ( online ).

- ↑ Melanie B. Weber: The 10 best reasons for a home birth. ( Memento of the original from November 10, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ten.de. The best lists.

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office : Almost a third of all hospital deliveries by caesarean section. ( Memento of the original from November 15, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Press release No. 098 from March 19, 2012.

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office: Share of deliveries by caesarean section rises to almost 30%. ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Press release from February 7, 2007.

- ↑ Fact check caesarean section. Caesarean section births - development and regional distribution . Bertelsmann Foundation, 2012.

- ↑ In North Rhine-Westphalia often caesarean section. In: Rheinische Post . June 5, 2010, archived from the original on February 12, 2013 ; accessed on April 2, 2018 .

- ↑ Laila Daneshmandi: Every third birth with caesarean section. In: Kurier.at , November 23, 2012.

- ↑ FIGO, Committee for the Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women's Health: Statement by the Committee on the publication of the present ethical guidelines 1998. In: Obstetrics and Frauenheilkunde , 59, 1999, pp. 123–127.

- ↑ Techniker Krankenkasse ( Memento of the original from September 16, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung (2010)

- ↑ Martin S. Spink: Arabian Gynaecological, Obstetrical and Genito-Urinary Practice illustrated from Albucasis. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Volume 30, 1937, pp. 653-671.