Animal experiment

Animal experiments are scientific experiments on or with living animals . One also speaks of laboratory animals . The aim of animal experiments is to gain knowledge in basic research and to develop and test new medical therapy options. Research with laboratory animals is carried out in universities and research institutions , pharmaceutical companies and service companies. Most animals are bred for research purposes, very few are caught for it. According to estimates, between 58 and 115 million vertebrates worldwide - mainly breeding forms of house mice and brown rats , but also hamsters , guinea pigs , rabbits , ferrets , dogs and primates - were used for animal experiments worldwide . Many test animals die during the experiments or are killed afterwards. The validity of animal experiments has been proven, their ethical justifiability is controversial.

history

The first surviving reports of animal experiments come from the fifth century BC in ancient Greece. In the Hippocratic writing About the Heart around 300 BC Chr. Studies on living animals to study the heart and the swallowing process mentioned. At the beginning of modern times, Andreas Vesalius dissected corpses and carcasses in order to obtain anatomical insights. René Descartes also dissected living animals around 1633, for example to observe blood circulation. He advocated the new thesis at the time that animals would not feel pain.

The Latin term vivisection has long been in international use for all types of animal experiment:

- "Vivisection: The word describes any type of animal experiment, whether the animals are dissected or not." ( Encyclopaedia Americana )

- Vivisection: In general, any type of animal experiment, especially if it causes pain to the subject. "( Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary )

- "Vivisection: intervention on living animals for scientific experimental purposes." ( Duden ).

At the end of the 20th century, the term Tierversuch had established itself in German-speaking countries as the basic term for the experimental use of living animals in pharmacology, physiology and other disciplines.

Definition and legal basis

Europe

Legislation within the European Union is based on Directive 86/609 / EEC from 1986. This is intended to implement the "Three-R rules" (Reduction, Refinement, Replacement) mentioned in 1959 by the zoologist William Russel and the microbiologist Rex Bruch Help breakthrough.

- Reduction stands for the goal of reducing the number of animals required for the experiments.

- Refinement means the improvement in the sense of a reduction of pain and stress for the animals and

- Replacement means the replacement of animals as often as possible with in-vitro tests or in-silico tests (literally "in silicon"), i.e. computer models.

Directive 86/609 was replaced on September 22, 2010 by Directive 2010/63 / EU of the European Parliament and the Council. This directive is based on Article 13 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) . This guideline extends guideline 86/609 in particular to include further aspects relating to the breeding and protection of laboratory animals.

Germany

Controversy about animal experiments in the German Empire up to the Reich Animal Protection Act 1933

An important concern for the early animal protection movement in the German Empire was, in addition to the establishment of animal shelters, in particular a ban on vivisection . Prominent pioneers like Richard Wagner not only called for the abolition of animal experiments, which for Wagner and many of his followers, along with the ritual slaughtering, symbolized “evil and the Jewish” in its purest form, and also called for a renunciation of meat consumption. With the exception of the “ Gossler Decree ” in Prussia in 1885, which moderately tightened the existing regulations, animal protection initiatives were downright ignored. Animal welfare concerns found favor with anti-Semites and German nationals as well as with life reformers who called for a move away from modern, “Jewish” science towards German folk and natural medicine. From 1871 to 1933 the animal welfare organizations grew from several dozen to over 700 different associations and organizations.

This concern was taken up by the Nazi regime and immediately after 1933 put into practice with great propaganda effort. For the National Socialists, animal welfare was a welcome and popular topic - also because fur traders such as practical and academic doctors and biologists were often Jews and with animal welfare arguments not only questioned their professional existence, but also their cultural existence beyond the prohibition of religiously conditioned slaughter Life was pressurized. After the seizure of power in 1933, work began on April 1, 1933 with high pressure and with intensive cooperation from the animal welfare associations on a pathocentric animal welfare law. On August 16, 1933, more than three months before the Reich Animal Protection Act was enacted, Hermann Göring, in his role as Prussian Prime Minister, declared the "vivisection of animals of all kinds for the entire Prussian state territory" to be prohibited. The simultaneous threat of imprisonment in a concentration camp for animal experimenters as part of a radio address was one of the first public mentions of the concentration camps and put animal testers on a par with high-ranking political opponents of the regime. However, it did not stop with a complete ban on animal experiments, but significant restrictions and an external approval process were introduced. The animal welfare associations were not involved in the approval process and were brought into line after 1933.

The National Socialist idea of animal protection granted protection to selected animals as part of an Aryan and nature-loving national community, which was not granted to victims of human experiments with often fatal results. In addition, animal experiments were seen as legitimate and carried out without hesitation for so-called "war-important" projects and in the service of "public health", for example in sterilization experiments and trials for aviation technology.

Legal situation

The legal basis in Germany is the Animal Welfare Act , in particular Sections 7-10a. According to § 1 of the German Animal Welfare Act, animals are recognized as "fellow creatures" and inflicting pain, suffering or harm without a reasonable cause is prohibited. Animal experiments are regulated in Sections 7–9 of the Animal Welfare Act. First, principles for animal experiments are laid down (definition; avoidance of pain, suffering or damage; ethical justification, indispensability for the scientific research project). According to § 7 , animals may be inflicted with pain, suffering and harm in order to prevent, recognize or treat diseases, to recognize environmental hazards, to test substances or products for their harmlessness and in the context of basic research .

Animal experiments within the meaning of the German Animal Welfare Act are experiments on living animals. The killing of an animal, for example to carry out experiments on its organs or tissues, is therefore not an animal experiment in the legal sense. The change in the genetic material of animals falls under the term animal experiment "if it can be associated with pain, suffering or damage for the mutated animals or their carriers".

According to Section 8 , animal experiments on vertebrates are generally subject to approval, unless they are carried out on the basis of laws, ordinances, judicial orders, for the purposes of vaccination, blood collection or other diagnostic measures. According to § 8a , these excepted cases, as well as animal experiments on decapods and cephalopods , only need to be reported to the competent state authority. The Animal Welfare Act regulates in detail which documents must be attached to the application. So z. B. be scientifically justified in detail, why you absolutely have to carry out this experiment on animals. In addition, evidence of suitable personnel, spatial and organizational equipment must be submitted. Certain experimental projects are exempt from the permit requirement, but they must at the authority in an appropriate form appears to be. These are, on the one hand, experiments that are prescribed by national laws or legal acts of the European Union, and on the other hand, experiments that are not associated with any pain, suffering or harm for the animals (e.g. blood sampling to obtain cells for Cell cultures). Due to the increased use of non-animal testing methods, the proportion of animal tests carried out by legal regulations has been falling for years: in 1991, their proportion was 35% (around 842,000 animals), in 2000 it was 21% (389,000) and in 2004 it was 15% (350,000 animals ). In 2005 the number of animals increased again (454,000 = 19%).

Furthermore, it is stipulated that every facility that wants to carry out animal experiments must appoint an animal welfare officer. These must either be veterinarians, doctors or biologists specializing in zoology. You are responsible for ensuring compliance with animal welfare regulations on the farm and for advising the people who handle the animals.

According to the Animal Welfare Act, only people with the appropriate qualifications are allowed to carry out experiments on animals. This includes studying veterinary medicine or a comparable qualifying scientific training (e.g. in human medicine, biochemistry, biology or as a corresponding technical assistant) in connection with a corresponding further education ( certificate of competence ).

The Animal Welfare Act sees the highest priority as minimizing pain, suffering or damage to animals. Therefore, potentially painful animal experiments (e.g. operations, tissue transplants) must always be carried out under anesthesia and adequate pain relief. The law only provides for exceptions if either the anesthesia would be more stressful for the animal than the intervention alone or if it is contrary to the purpose of the experiment.

The approval authorities, usually the responsible regional council or the state health authorities , are supported by an ethics committee when deciding whether to approve animal experiments (Section 15 TierSchG). The majority of these commissions are made up of expert veterinarians, doctors and natural scientists, and at least one third is made up of lists of suggestions from animal welfare organizations.

In 2018, the Permanent Senate Commission for Animal Experimental Research of the German Research Foundation addressed problems in the practice of approval procedures for animal experiments since the 2013 amendment to the Animal Welfare Act. These hindered the aim of promoting uniform animal welfare standards and would have negative consequences for biomedical research in Germany. The opinion is based on a nationwide survey and several rounds of talks with experts.

Databases for animal experiments in Germany

Which animal experiment projects are approved by the responsible state authorities can be researched in the AnimalTestInfo database . The AnimalTestInfo database for animal experimentation projects in Germany contains easily understandable project summaries of the animal experimentation projects whose implementation has been applied for by scientific research institutes at universities, industry and the federal government and approved by the responsible authorities of the federal states. Applicants are responsible for the content of the published project summaries. The database is located at the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR). The legislature has given the BfR the legal mandate to anonymously publish the project summaries of approved animal experiments in Germany (Section 41 (1) sentence 1 TierSchVersV).

The German Center for the Protection of Laboratory Animals (Bf3R) is also located at the BfR. The center coordinates all activities nationwide with the aim of limiting animal experiments to an essential level and ensuring the best possible protection for laboratory animals. In addition, the work of the center should stimulate national and international research activities and promote scientific dialogue. An integral part of the Bf3R is the ZEBET - the "Central Office for the Collection and Evaluation of Alternative and Complementary Methods to Animal Experiments". ZEBET is one of five areas of competence of the Bf3R. It was founded in 1989 with the aim of limiting the use of animals for scientific purposes to the absolute minimum and developing alternatives to animal experiments. ZEBET researches, develops and validates alternative methods according to the 3R principle in its own laboratory. The Bf3R also runs the Animal Study Registry , an online register in which researchers can voluntarily register their research projects that include animal experiments. The information in this register is not anonymous and will be made public no later than five years after entry.

“Understanding animal experiments”, information initiative of German science

To represent science in Germany, the Alliance of Science Organizations has launched the “Understanding Animal Experiments” initiative. According to its own statements, the initiative wants to provide “comprehensive, up-to-date and fact-based” information about animal experiments in research. “Understanding Animal Experiments” offers an internet platform, communicates on social media and provides experts.

Austria

In Austria , the federal law of September 27, 1989 provides the legal basis. Only the intervention on living animals is referred to as an animal experiment. The intervention must be approved in advance by the competent authorities. The animal research director also receives approval from the authorities for this one animal experiment. The Austrian Animal Experiments Act provides for a control commission that can annually inspect every animal experiment laboratory without prior notification. A “non-existence” of this control or a violation of the legal situation will result in the immediate suspension of the approval and criminal proceedings.

In Austria, animal experiments for cosmetics and animal experiments on great apes are prohibited by law. Furthermore, state subsidies and state awards for the development of alternatives to animal experiments are advertised, promoted and financed every year.

Areas of application

Specially bred animals are mostly used for animal experiments, as precise data on these animals are required for meaningful results, e.g. B. their average lifespan, but also data on which diseases (cancer, diabetes, etc.) occur how often in the population. According to German and European law it is stipulated that only animals bred for experimental purposes may be used and that this may only be deviated from in justified exceptional cases. Animals captured in the wild are very rarely used for these reasons.

Basic research

At 64.3%, most animal experiments in the field of basic medical research were carried out in Switzerland in 2018 .

Drug research

In 2005, 21% of the animals used in animal experiments in Germany were required for research and development of products and devices for human, dental and veterinary medicine. Since many human diseases do not occur spontaneously in animals, various processes induce symptoms in the animal that are similar to human diseases (see also: model organism ). The vast majority of animals in this category are mice and rats (2005: 92%).

In the 21% of all animal experiments, the prescribed toxicological or other safety checks of drugs and medical devices are not included. According to the Association of Research-Based Pharmaceutical Manufacturers (VFA), 86% of the animal experiments carried out in the pharmaceutical sector relate to the examination of pharmaceuticals for their safety, quality and effectiveness ( pharmaceutical research ).

Manufacture and quality control of products

Almost 14% of animal experiments in 2005 were in the area of product manufacture and quality control.

Toxicology (toxicity tests)

The toxicity determinations were in 2005 with 6.6% in fifth place in the official animal experiment statistics. New active ingredients and chemicals are tested for possible harmful effects. With the entry into force of the EU chemicals directive REACH regulation on July 1, 2007, a considerable increase in animal experiments in the toxicological field was expected. 30,000 chemicals that came onto the market before 1981 are to be tested largely in animal experiments with regard to their danger to humans and the environment.

Behavioral research

Defense Research

Other areas

Animal experiments are also used to diagnose diseases such as rabies and to test pesticides . Animal experiments are also carried out in space travel to test life support systems and to research the effects of cosmic environmental conditions. The dog Laika became particularly famous in 1957. She was the first living creature to be sent into orbit and died there, presumably of stress and overheating.

Use of animals outside of animal testing

The use of animals for purposes that are not covered by § 7 and § 8 of the TierSchG and therefore do not constitute animal experiments in the legal sense are listed in Germany in the regular publications of animal use statistics by the responsible state offices in addition to animal experiments.

Study and training

In Germany, around 2.3% of laboratory animals are used for training and further education. It is primarily about the illustration of the theoretical subject matter in the study of biology , human and veterinary medicine . For example, rats are killed in order to learn about the structure and spatial arrangement of the internal organs of a mammal . In killed frogs, for example, the interaction of nerves and muscles can be demonstrated, since these organs remain functional for some time after death.

Students at universities in North Rhine-Westphalia and Saarland can be exempted from exercises on animals or parts of them that have been killed specifically for this purpose with the help of the higher education framework law of these countries.

Killing for scientific purposes

Around 25% of the animals used in 2005 were sacrificed in order to harvest cells or organs . The cells obtained are often required for cell cultures, which in turn replace animal experiments.

cosmetics

Animal testing for cosmetics has been banned in Germany since 1998 and since 2004 in the EU. The EU Cosmetics Directive (2003/15 / EG) also provides for an EU import ban implemented in two stages (2009 and 2013) for new cosmetic products tested in animal experiments. Dispensing with animal testing of end products does not rule out individual ingredients being tested in animal experiments, as the guideline relates to ingredients that are exclusively developed and manufactured for use in cosmetics, and the ingredients are new When the directive comes into force, substances developed must act. Ingredients tested in animal experiments that are also used for other purposes, for example under the EU chemicals directive , can still be imported.

Examples of test series

In medical research

Depending on the objective and the animals used, very different experimental setups can be used.

The most common test series in medical research are series of eight to ten animals (mostly mice or rats, the exact number depends on the biometric test planning), each of which is injected with a different dose of a certain active ingredient. After a certain, predetermined time, for example, blood is taken in order to analyze degradation products of the active ingredient. In most cases, the test animals are killed at the end of the test in order to be able to examine the influence of the active substance on internal organs.

The effects and side effects of hormone preparations such as birth control pills are usually examined in young female rats whose ovaries have been removed before the drug is administered. These drugs, which are taken almost daily and often for years by healthy young women and must therefore be particularly safe, are an example of the fact that many active pharmaceutical ingredients still have to be tested in living animals: The main effect (the maintenance of a certain Hormone concentration in the body) in direct connection with possible side effects (change in fat or water storage in the tissue) and the natural breakdown products of the active ingredients.

In the chemical and cosmetics industries

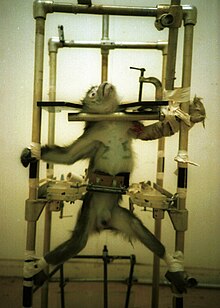

A test procedure in the chemical and cosmetics industry is, for example, testing the mucous membrane-irritating properties of substances on rabbits, the Draize test . For this purpose, the test animals are often dripped in significantly concentrated amounts of the substances to be tested into the eyes, which react as sensitively as human eyes. To ensure that they cannot wipe the substances out of their eyes, the rabbits are locked in boxes during the test series with their heads protruding outside. Several alternative methods with cell cultures and incubated chicken eggs were developed as early as the 1980s . Some of these test systems are already in use today. In 2005, 505 rabbits were used in Germany for the mucous membrane irritation test.

Type and number of animals used

Germany

Since January 1, 1989, the Laboratory Animal Registration Ordinance in Germany has imposed a legal obligation to record the animals used for scientific experiments. The German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture has published corresponding statistics every year since then. It should be remembered that these figures “only record those animals that were actually used in an approved animal experiment. However, to create a new genetic line with the desired properties, a significantly larger number of animals is required. A large number of these animals cannot be used in any animal experiment due to the lack of a targeted phenotype and are therefore superfluous. Even optimal trial and breeding planning cannot prevent this. "

The numbers initially fell from 2.6 million in 1989 to 1.5 million in 1997. Since then they have been increasing again. For the year 2014, the ministry speaks of around 2.8 million vertebrates that were used for scientific experiments.

In 2017, around two million animals were used for scientific animal experiments in Germany. With 1.37 million animals, mice were the most commonly used that year. The rest is divided between 255,000 rats, 240,000 fish, 3,472 monkeys and 3,300 dogs and 718 cats. About 50% of all animals were used in basic research. 27% involved the manufacture or review of drugs. In another 15% diseases were researched. Approx. 740,000 of the two million animals died or were killed.

Austria

In 2005, 167,312 animals were used in experiments in Austria, including 128,634 mice, 11,920 rats, 18,439 rabbits, 3,149 guinea pigs, 1,199 fish, 85 dogs, 12 cats and 56 monkeys. In 2012 the number rose slightly to 184,610 animals. These included 149,440 mice, 7,270 rats, 15,480 rabbits, 2,790 guinea pigs, 3,823 fish, 74 dogs and 33 cats. Monkeys were not used in 2012. It should be noted that the Austrian statistics only show animals that were actually used in animal experiments. Animals that were specially bred for experiments with permission, but subsequently killed because they were superfluous and fetuses and embryos do not have to be reported to the authorities.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, 550,505 animals were killed for use in experiments in 2005, including 361,693 mice, 136,657 rats, 10,818 fish, 6,488 rabbits, 6,757 birds, 3,071 dogs, 409 cats and 408 monkeys. The reason for the comparatively high number is the importance of the Swiss pharmaceutical and chemical industry.

For comparison: In 1985 there were 170 horses, 690 cats, 705 cattle, 736 monkeys, 1,386 sheep and goats, 1,525 pigs, 3,096 dogs, 4,531 amphibians and reptiles, 20,396 birds, 34,608 fish and 1,489,000 rats, mice and hamsters and guinea pigs were killed, a total of 1,556,843 animals.

Europe

| Animal species | Number in millions |

|---|---|

| Mice | 6.42 |

| Rats | 2.34 |

| fishes | 1.75 |

| Birds | 0.65 |

| Rabbits | 0.31 |

| Guinea pig | 0.26 |

For Europe these figures result for the year 2005 (table opposite; this includes animals that were used in tests that caused pain, suffering and permanent damage.) The purposes of the 12.1 million animals used in 2005 The breakdown was as follows: more than 60% for research in the fields of human medicine, veterinary medicine, dentistry and biology, 8% for toxicological tests and other safety assessments. 78% were rodents and rabbits, 15% cold-blooded animals and 5% birds.

United Kingdom

In the UK, around 3 million animals are used in trials each year.

United States

Exact statistics are not available for the United States, as rats, mice and birds are exempt from the Animal Welfare Act , but make up the largest proportion of the animals used. Conservative estimates for the number of animals consumed annually start at 20 million. Under certain conditions, a proof of efficacy in animal experiments ( Animal Efficacy Rule ) is sufficient for the approval of a new drug in the USA .

Evaluation of animal experiments

On the occasion of the upcoming revision of Directive 86/609 / EEC on the protection of animals used in experiments, the EU Commission carried out an online public survey on the subject of animal experiments from June to August 2006. The vast majority of around 43,000 citizens from 25 countries who took part in the survey were in favor of more animal welfare . More than 90% of the participants said that the EU and the government should ensure significantly more animal welfare in the field of animal experiments in their own country, especially for monkeys, dogs and cats. The vast majority of those questioned were in favor of improved protection for mice (87%), fish (83%) and fruit flies (60%). On the other hand, 40% of the respondents considered animal experiments to be acceptable for the purpose of developing therapies and drugs. At the same time, 85% of respondents said that animal welfare organizations were the main source of information about animal experiments. Almost all participants wanted more transparency and a say in terms of when and how an animal experiment can be carried out. Around three quarters of those questioned did not see the medical progress or competitiveness of Europe at risk from animal welfare regulations. Just as many people were in favor of greater support for the development and recognition of animal-free methods.

Arguments in favor of animal testing

Knowledge gain

Representatives of research based on animal experiments , such as the German Research Foundation , state that all important findings in the field of medicine can be traced back to animal experiments: experiments on dogs and rabbits have led to the discovery of insulin and helped to understand the effects of this hormone and new therapies for developing diabetes . According to the German Research Foundation, further examples of the benefits of animal experiments in medicine are the development of vaccine serums, for example. B. against diphtheria (guinea pigs), against yellow fever and polio (mouse and monkey) as well as studies on the development of the disease of tuberculosis (sheep and cattle), typhus (mouse, rat, monkey) and malaria (pigeon).

In surgery , animal experiments have developed new techniques and surgical methods have been refined. First attempts to transplant tissue were made on mice as early as the beginning of the 20th century. Other important research areas are studies of the functioning of the nervous system , the cardiovascular system and the mode of action of hormones, as well as cancer research. Refraining from animal experiments would "mean a slowdown in medical progress and thus significantly reduce the chances of recovery for sick people", according to the German Research Foundation.

Transferability

When it comes to the question of the transferability of the results, advocates of animal experiments cite the great similarity between humans and animals with regard to cell and organ function. In particular, the components of body cells and the biochemical mechanisms in the cells, which underlie all life processes, are very similar in the various animal species. A transfer from animals to humans is therefore particularly possible if the species-specific characteristics are also taken into account. This basic assumption applies to both the desired and the harmful and toxic effects of a substance. In particular, the complex interaction of active ingredients and their breakdown products with different organs can in many cases only be reliably understood in living animals.

Expressiveness

Despite significant progress in the area of alternative methods, for example with cell cultures and computer simulations, these methods cannot replace the "intact organism", according to the German Research Foundation. Cell culture reaches its limits, especially when the complex interaction of several organ systems is to be examined. If, for example, the role of the immune system in the digestive tract or the effect of new vaccines is to be investigated, a large number of different organs would have to be simulated, as complex higher control mechanisms play a role.

Ethical reasoning

The ethical argumentation assumes that people's interests in maintaining their health are fundamentally valued higher than the protection of other living beings. The possible harm (pain, death) in animals associated with the experiments are z. B. justified with the development of drugs for humans. In 2005, 45 percent of respondents across the EU felt that scientists should have a right to conduct research on animals if it would solve human health problems.

Proponents of animal experiments are convinced that the approval process excludes senseless and ethically unjustifiable animal experiments. Ultimately, the researcher must demonstrate that there is an “indispensability” for the planned experiment, that is, that there are no equivalent alternatives - measured against the intended purpose. The question of “ethical justifiability” is about weighing up the stress on the animal on the one hand and scientific knowledge on the other.

In the opinion of those in favor of animal experiments, animal experiments can certainly also be associated with pain and suffering for the animals, but heavy loads would - wherever possible - be avoided because they would have an impact on the test result. Proponents of animal experiments also argue that animals are kept as appropriate to their species as possible.

Finally, advocates of animal experiments point out that it is not ethically justifiable to conduct clinical studies and other experiments on humans without prior animal experiments if it is possible to at least estimate the risks associated with the study for the test persons with the help of previous animal experiments.

Arguments against animal testing

Knowledge gain

According to opponents of animal testing such as B. the doctors against animal experiments is the state of today's medicine, which is based to a large extent on animal experiments, no proof of the need for animal experiments. Although the progress made is recognized by many opponents of animal experimentation, it is not in an acceptable relationship to the effort and number of animals used. In addition, knowledge can now also be obtained using other methods, such as the use of cell cultures in vitro . One example is the work of the winners of the Herbert Stiller Prize , which was awarded for research into human diseases without animal experiments.

It is also argued that animal experiments do not lead directly to findings that can be used by humans, but that they would prove to be a dead end. For example, a study on the clinical relevance of animal experiments came to the conclusion that, ten years after their implementation, no implementation in human medicine could be demonstrated in 16 animal experiment projects examined.

Transferability

Opponents of animal experiments cite the many differences between animals and humans in terms of body structure, organ function and metabolism . Animals of different species would react differently to chemicals and drugs . For example, asbestos only causes cancer in rats at a dose that is 300 times higher than in humans. Medicines (e.g. thalidomide ) that were considered safe on the basis of animal experiments and which caused serious or even fatal side effects in humans are proof that the results of animal experiments cannot be transferred to humans with the necessary reliability. The gene response in mice also differs significantly from that of humans in inflammatory processes, which is why the results of mouse experiments cannot always be transferred to humans.

Expressiveness

Opponents of animal experiments doubt the informative value of animal experiments, since animals are indeed an entire organism , but the wrong one. Animal testing-free methods with human cells and tissues, combined with special computer programs, in their opinion, provide just as precise and meaningful results in some areas compared to animal testing, with better ethical justification.

In animal research, important aspects of disease development such as diet, lifestyle, use of addictive substances, harmful environmental influences, stress , psychological and social factors are also disregarded. Many opponents of animal experimentation feel that it is a better way to concentrate on studies on humans, whereby the areas of epidemiology , clinical research and occupational and social medicine in particular need to be expanded.

Ethical reasoning

Many opponents of animal experimentation question the argument that human interests have priority over the interests of other living beings, in whole or in part. As a sentient subject, the animal is entitled to treatment that is morally equal to that of fellow human beings. In this respect, killing animals and inflicting pain are morally inadmissible. This line of argument can also be found in vegetarianism , for example . In animal experiments, animals are degraded to measuring instruments, which does not correspond to the dignity of the living being. A purely utilitarian view, according to which it is a matter of mere considerations of utility, cannot be the basis for the ethical assessment of animal experiments.

The Austrian animal rights activist Helmut F. Kaplan builds on this argument and justifies his negative attitude towards animal experiments as follows:

“That is why the factual question of whether animal experiments are useful for humans is morally irrelevant: animal experiments are wrong, regardless of whether they are useful for humans. The legitimate question is not, 'What is the maximum health we can produce?' But 'How much health can we produce in an ethically permissible manner?' The - real or supposed - usefulness of animal experiments is not an ethical argument at all: There are many things that would be useful but are nonetheless immoral and forbidden, for example human experiments. "

However, there are also utilitarians who criticize animal experiments. The animal ethicist Peter Singer calls for the interests of humans and animals to be weighed fairly. Although this could theoretically turn out to be in favor of the experiments, the interests of the animals concerned are usually much stronger. He argues that laboratory animals are either so similar to humans that similar ethical standards must also apply to them and that animal experiments are therefore prohibited for the same ethical concerns as human experiments, or that laboratory animals are so dissimilar to us that the results are of less use to humans to have.

Alternatives

In the sense of the "3 R" ( Reduction, Refinement and Replacement ), methods to replace animal experiments are being intensively researched today, with considerable progress being made in recent years (see also the Basel Declaration ).

Nowadays, so-called in-vitro methods are available for many questions . This is understood to mean tests carried out "in a test tube". Toxicological studies can also be carried out on microorganisms and cell cultures in very small volumes, e.g. B. in microfluidic systems ( microtoxicology ). Today, some drugs can be developed in silico , i.e. on the computer, and applied to human cell and tissue cultures, e.g. B. are available from operations can be tested. The skin-irritating properties of chemicals and cosmetic substances can be tested on artificial skin. A test with human blood is now available for testing feverish impurities in drugs and vaccines . Biology, human and veterinary medicine students can understand physiological relationships in films, computer simulations or in painless self-experiments. Surgical interventions can be practiced on models that function similarly to flight simulators . American scientists have found a way to represent a kind of organism with metabolism on a microchip . Tiny chambers made of glass tubes are lined with living cells and represent individual organs. New active ingredients can be tested in the artificial body. Research into the brain can be carried out directly on humans using non-invasive methods, for example with computed tomography , although these are only of limited applicability because, with their macroscopic-topographical approach, they cannot offer the necessary resolution to precisely target single-cell To be able to measure level, as is required, for example, for researching neural coding mechanisms in neurobiology .

The Central Office for the Collection and Evaluation of Alternative and Complementary Methods for Animal Experiments (ZEBET) at the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) is responsible for validation, i.e. the comparison between the animal experiment-free method and the corresponding animal experiment as well as recognition at national and international level . ZEBET also operates a database of validated alternative methods (AnimAlt-ZEBET). At the European level, the European Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ECVAM) deals with the research, development and validation of animal-free methods. Both institutions operate internet databases on non-animal testing methods. The EVCAM data can be accessed through the Centre's SIS database.

Marking of animal-free products

The German Animal Welfare Association maintains a positive list of cosmetics in which manufacturers and distributors of cosmetics are listed who refrain from animal testing. The provisions also include testing of raw materials and third party testing. Products that are therefore not tested on animals are marked with a trademark.

There is also a test mark of the BDIH, the Federal Association of German Industrial and Trading Companies for pharmaceuticals, health foods , dietary supplements , personal care products and decorative cosmetics , with the label “Controlled Natural Cosmetics”, which indicates freedom from animal testing. The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) issues an internationally recognized label for cruelty free products.

literature

- LFM van Zutphen, V. Baumans, AC Beynen: Basics of laboratory animal science . Enke-Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-432-29101-9 .

- Anton Mayr: Virological working methods I. Cell cultures, incubated chicken eggs, laboratory animals . Urban & Fischer Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-437-30175-6 .

- Corina Gericke: Everything you always wanted to know about animal testing . Echo-Verlag, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-926914-45-9 .

- Johann S. Oh: Why you shouldn't torture Lassie. Animal testing and moral individualism . Harald Fischer Verlag, Erlangen 1999, ISBN 3-89131-119-2 .

- Karin Blumer: Animal experiments for the benefit of humans? Ethical aspects of animal experiments with special consideration of transgenic animals. Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-89675-398-3 .

- Franz Paul Gruber, Horst Spielmann (ed.): Alternatives to animal experiments . Spectrum Academic Publishing House, Heidelberg / Berlin / Oxford 1996, ISBN 3-86025-195-3 .

- Bernhard Rambeck: The Myth of Animal Experiments . Zweiausendeins, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-86150-178-3 .

- Helga Kuhse, Peter Singer : A Companion to Bioethics (Blackwell Companions to Philosophy) . Blackwell Verlag 1998, ISBN 0-631-19737-0 .

- Arianna Ferrari: Genmaus & Co - Genetically Modified Animals in Biomedicine. Harald Fischer Verlag, Erlangen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89131-418-0 .

Web links

Europe

Germany

- Society of Laboratory Animals (GV-SOLAS)

- German Center for the Protection of Laboratory Animals (Bf3R)

- The importance of animal experiments for research at the German Reference Center for Ethics in the Biosciences

- Information on animal experiments in research and the new edition of the brochure (2016) on the website of the German Research Foundation

- www.stiftung-set.de - Foundation for the promotion of research into alternative and supplementary methods to restrict animal experiments (SET)

- www.aerzte-gegen-tierversuche.de - Doctors Against Animal Experiments e. V.

- www.tierrechte.de - "People for Animal Rights" / Bundesverband der Tierversuchsgegner e. V.

- Information about animal experiments on the VBIO homepage

- www.tierversuche-verhaben.de/ - Initiative of German science, coordinated by the Alliance of Science Organizations

Switzerland

- Animal experiments - information from the Federal Food Safety and Veterinary Office

- Swiss anti-animal experimentation group

Individual evidence

- ↑ K. Taylor, N. Gordon, G. Langley, W. Higgins: Estimates for worldwide laboratory animal use in 2005. In: Altern Lab Anim. Volume 36 (3), 2008, pp. 327-342. PMID 18662096 .

- ↑ Andreas-Holger Maehle: animal experiments. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 1398 f .; here: p. 1398.

- ↑ Bayer AG: When were the first animal experiments? (No longer available online.) Bayer AG, February 23, 2016, archived from the original on August 21, 2016 ; accessed on October 8, 2016 .

- ↑ Silvia Federici : Caliban and the Witch. Women, the body and the primordial accumulation. From the Engl. Max Henninger. Mandelbaum Verlag, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-85476-670-4 , pp. 186 and 200f

- ^ A b Pietro Croce: Animal experiment or science: a choice. Book publisher CIVIS Publications, Massagno 1988, ISBN 3-905280-05-7 , p. 21.

- ↑ Duden. Volume 1: The German spelling. 24th, completely revised and expanded edition. Dudenverlag, Mannheim / Leipzig / Vienna / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-411-04014-9 , p. 1089.

- ^ Pschyrembel Clinical Dictionary. 255th edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1986, ISBN 3-11-007916-X , p. 1672.

- ↑ a b Didier Buysse: The controversial sacrificial altar of progress. in research eu , special edition October 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Article 13

- ↑ A. Arluke, as Sax: Understanding Nazi Animal Protection and the Holocaust. In: Anthrozoic. H. 5, 1992, pp. 6-31.

- ↑ KP Schweiger: "Old Wine in New Hoses": The dispute over the scientific animal experiment in Germany 1900-1935. Dissertation . Göttingen 1993. (The struggle in Germany around scientific animal testing 1900-1933)

- ^ A b Helene Heise: Love of animals, misanthropists. Hitler's affection for his German shepherd “ Blondi ” is legendary. The history of the “Reich Animal Protection Act” of 1933 proves that strict animal protection and contempt for people for the Nazis went hand in hand. In: Spiegel online. September 19, 2007.

- ↑ Animal Welfare Act. Juris, accessed October 8, 2016 .

- ↑ a b German Animal Welfare Act ( Memento from January 28, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection

- ↑ Press release DFG calls for improvements in approval procedures for animal experiments September 5, 2018

- ^ Opinion: Approval procedure for animal experiments September 2018

- ↑ AnimalTestInfo - database for animal experiment projects in Germany

- ↑ Questions and answers on the German Center for the Protection of Laboratory Animals (Bf3R). (No longer available online.) Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR), January 29, 2016, archived from the original on March 24, 2016 ; accessed on March 17, 2016 .

- ↑ About us: Understanding animal experiments - An information initiative of science. Alliance of Science Organizations , September 6, 2016, accessed September 8, 2016 .

- ↑ Press release of the alliance organizations on the start of the "Understanding Animal Experiments" initiative

- ↑ tv-statistik.ch

- ↑ VFA position paper on animal experiments in pharmaceutical research

- ↑ Use of laboratory animals in 2016 (Fig. 3)

- ↑ Kill, cut open, throw away: animal experiments in studies. Retrieved January 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Directive 2003/15 / EC

- ↑ Justyna Chmielewska, Bettina Bert, Barbara Grune, Andreas Hensel, Gilbert Schönfelder: The “sensible reason” for killing excess animals. A classic question of animal protection law in the context of biomedical research . In: Nature and Law . Vol. 37, No. 10 , October 10, 2015, ISSN 0172-1631 , p. 677-682 , doi : 10.1007 / s10357-015-2903-9 (second ISSN 1439-0515 ).

- ↑ Number of animals used for scientific purposes in 2014.

- ↑ a b dpa: 740,000 animals killed: Animal experiments: Around 2.8 million animals used or killed . In: The time . December 20, 2018, ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed October 16, 2019]).

- ↑ Official statistics of the Federal Ministry for Science, Research and Economy, 2005 ( Memento from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Official statistics of the Federal Ministry for Science, Research and Economy, 2012

- ↑ § 2 (3) Animal Experiments Statistics Ordinance 2013 (PDF)

- ↑ Current '87. Chronik-Verlag, 1986, ISBN 3-88379-081-8 , p. 264.

- ↑ Focus news magazine, issue 48/07 of November 26, 2007, p. 20: "Focussed" - source is the EU Commission

- ↑ a b Helga Kuhse, Peter Singer: A companion to bioethics . Ed .: Wiley-Blackwell. Chichester, UK / Malden, MA 2009, ISBN 978-1-4051-6331-6 , pp. 499 (English).

- ↑ EU citizens demand stricter animal welfare regulations

- ↑ German Research Foundation: Animal Experiments in Research, 2016 PDF, download

- ↑ Survey: Europeans for more research funding ORF-online from June 13, 2005 (dump from January 21, 2010)

- ^ What Animals Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy . Oxford University Press , 2004, p. 76, Fig. 4.2

- ^ Doctors against Tierversuche eV

- ^ Herbert Stiller Prize, winners accessed on April 24, 2011.

- ^ T. Lindl et al.: Animal experiments in biomedical research. (PDF; 325 kB). In: Altex. 22, No. 3, 2005, pp. 143-151.

- ↑ K. Rödelsperger, H.-J. Woitowitz: Airborne fiber concentrations and lung burden compared to the tumor response in rats and humans exposed to asbestos. In: Annals of Occupational Hygiene . tape 39 , no. 5 , 1995, ISSN 0003-4878 , pp. 715-725 , doi : 10.1093 / annhyg / 39.5.715 , PMID 8526402 .

- ↑ PNAS (2013): Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases , accessed on February 12, 2013.

- ^ Deutsches Ärzteblatt (2004): Controversial relevance , accessed on January 8, 2012.

- ↑ Can animal experiments be justified ethically?

- ↑ Tools for Research. In: Peter Singer : Animal Liberation. The liberation of the animals . 2nd Edition. Rowohlt Verlag , 1996.

- ^ WMS Russell, RL Burch: The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. 1959. (Reprint: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW), 1992, ISBN 0-900767-78-2 )

- ↑ D. Freedman: guinea pig made of silicon. In: Technology Review. July 2004, pp. 45-48.

- ↑ ZEBET . Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ↑ AnimAlt ZEBET database . Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ↑ EVCAM . Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ DTB positive list

- ↑ Controlled natural cosmetics , BDIH guideline

- ↑ British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) (English) ( Memento from February 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive )