Silver Spring monkeys

The Silver Spring monkeys were a group of 17 Philippine macaque , the most Institute for Behavioral Research in Silver Spring ( Maryland , USA lived). In the 1980s, a dispute between researchers, animal rights activists, various courts and politicians made them “probably the most famous laboratory animals in history.” The experiments fell into the field of neural plasticity , where research is carried out on how the brains of primates track themselves Can reorganize accidents through therapy.

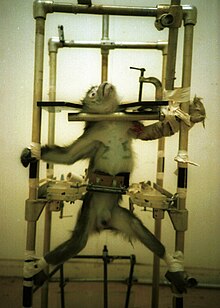

The psychologist Edward Taub first cut through parts of the spinal ganglion in the relevant series of experiments so that the animals could no longer perceive arms or legs. It was known from observations that people who had been damaged in this way were unable to use these body parts, and there was no neurological explanation for this at the time. Taub examined the behaviorist hypothesis that this non-use is a learned behavior . For checking purposes, he used self-made restraints, electric shocks, or food deprivation to force the animals to use the body parts they could no longer feel.

After traveling Europe and resuming his studies in the United States, Alex Pacheco joined the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) group as an activist , which then had around 20 members. With them he decided to work undercover at Taub's institute. After a while, he pointed out the living conditions of the monkeys to the police, thus triggering the world's first raid in an animal laboratory. Taub was subsequently charged with 17 animal cruelty and failure to provide veterinary care. He was initially convicted in six cases. Five of them were rejected in a renegotiation. The conviction in the sixth case was annulled on appeal because the court found that the Maryland Animal Welfare Act did not apply to state-funded laboratories.

After the two-year dispute over Taub's guilt in relation to animal cruelty, another eight years of legal battle over the whereabouts of the animals followed. That sparked a nationwide debate and a 1985 amendment to the Animal Welfare Act . The organization PETA grew during this time to 400,000 members with an annual donation of 5 million dollars. Other clubs were also popular, and the first cell of the North American Animal Liberation Front was formed. It was also the first animal welfare case to be heard by the Supreme Court . PETA tried to get her to take care of the monkeys. The last lawsuit in the case was dismissed in 1991 and the remaining animals were killed shortly thereafter.

In the subsequent autopsy , it was found that the cerebral cortex of the mutilated monkeys showed significant changes in contrast to the control group . The results of the experiments thus contradicted the generally shared assumption that the brain of primates cannot reorganize itself. The results of the experiments helped to overcome this assumption.

After Taub had received death threats for a number of years and was unable to find a job at a scientific institution, he was offered a position at the University of Alabama at Birmingham . Based on the concept of neuroplasticity, he developed the constraint-induced movement therapy , which enables some human victims of strokes to reuse paralyzed body parts.

Background and history

Edward Taub is a behavioral scientist currently (2019) doing research at the University of Birmingham. While studying philosophy at Colombia University , he became interested in behaviorist approaches. He completed his further studies with Fred S. Keller and William N. Schoenfeld , both experimental psychologists. He took a job in a laboratory to better understand the nervous system . There he was first introduced to "Deafferentation". An afferent nerve is a nerve that carries impulses from sensory organs via the spinal cord into the brain; Deafferentation is a surgical procedure that exposes the spinal cord and separates certain afferent nerves. Those affected can then no longer perceive the corresponding body parts and also lose the feeling for where they are spatially. In the 1981 court case, Taub testified that deafferented monkeys require extremely intensive care because they identify deafferented body parts as foreign objects and mutilate them, for example by chewing them off. Taub continued his work on deafferented monkeys at New York University , where he received his doctorate in 1970 . In what he called basic research , he carried out a large number of experiments on deafferented monkeys: he partially deafferented the whole body or deafferented embryos before birth, in order to insert them back into the uterus afterwards .

When Taub began his research, it was a scientifically prevalent view that primates could not use parts of the body that they could not feel. According to Norman Doidge , Taub's assumption was that patients did not use paralyzed body parts because healthy body parts were much easier to use. Taub called this phenomenon “learned non-use”. He tested this assumption by, for example, deafferentiating one arm and then fixing the functioning arm in a device. The affected monkeys then use their deaf arms several times to feed or move. This assumption was also confirmed by many other experiments in which both arms or the whole body were "made deaf". If the animals were forced to use deaf parts by deprivation of food or electric shocks, so did they.

Alex Pacheco grew up in Mexico and Ohio , was the child of a doctor and initially worked for a priesthood . He visited a slaughterhouse in the 1970s and then changed his life. He read Peter Singer's book Animal Liberation (1975), first followed a vegetarian diet and became an activist for animal rights . He hired on an anti-whaling ship the Sea Shepherd and joined after a few years at sea of the Hunt Saboteurs Association ( Society for hunting sabotage ) in England at. When he returned to the United States primarily because of the expiring visa , he began studying political science at Washington University . In March 1980 he met Ingrid Newkirk , who led the group People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals . They decided to create documentation on publicly funded animal testing laboratories and, while researching, came across Taub's institute. Taub offered Pacheco an unpaid position to work with the student Gergette Yakalis, which he took up in May 1981.

At the institute Taub carried out deafferentation experiments on 16 crab-eating macaques and one rhesus macaque . The animals were about 40 cm tall and each housed in a single cage measuring 45 × 45 cm. The cages contained no sleeping, litter, or employment. The cages were in a windowless and constantly lit room of 5 m². Pacheco writes that 12 of the 17 monkeys had at least one deafferent arm. According to the Journal Laboratory Primate newsletter , this affected 10 monkeys. The remaining animals were a control group .

The researchers named the monkeys Chester, Paul, Billy, Hard Times, Domitian, Nero, Titus, Big Boy, Augustus, Allen, Montaigne, Sisyphus, Charlie, Brooks, Hayden, Adidas, and Sarah. Sarah was purchased as a control animal from a Litton Laboratories dealer when she was one day old. From that day on she lived at the institute for eight years. Paul was the oldest of the monkeys. Both arms were deafferented to him. He'd chewed off all of his fingers on one hand, and chewed the skin and flesh off the palm of his hand, exposing the bones.

Searches and indictments

Pacheco later wrote that he found the monkeys in filthy circumstances. He found frozen bodies in a freezer and others immersed in formaldehyde . He reported that things like shoes, dirty clothes, feces and urine were strewn all over the operating room. The cages were covered with a layer of dirt. The excrement piled up on the floor or under the cages. Urine and rust gathered on every surface. The monkeys reached for food that had fallen through the bars onto the floor and into the excrement. He said the cages had not been cleaned for months and that there were no dishes that would allow the monkeys to separate their food from the excrement. The monkeys had no choice but to sit on the wiry floors of the cages. Francione also mentions that Taub used an amputated monkey hand as a paperweight .

“If a bandage was ever put on, it was never changed, no matter how dirty it got. Bandages remained until they rotted to the point where they fell off the injured limb. Old, rotten bandages stuck to the bottom of the cage, where they sucked up urine and feces. The monkeys also suffered from a variety of wounds that they had inflicted on themselves or that had been caused by other monkeys crossing from the neighboring cage. I saw discolored, exposed muscle tissue on her arms. In two monkeys, the bones had protruded through the flesh. Several had bitten off their own fingers and were now showing festering stumps that they held out to me when I secretly pulled fruit out of my pocket. With these pathetic limbs they searched the putrid dirt in their trash cans for something to eat. "

Pacheco decided to document the conditions and asked to be able to work at night. Taub was fascinated by Pacheco's involvement and even gave him keys to the laboratory. Pacheco took photos and shared them with some animal activists, including Cleveland Amory , who bought him better equipment and observed the outside of the institute on the following nights while Pacheco took photos inside. In August, Pacheco invited veterinarians and scientists to the laboratory to witness the conditions. Among them was Geza Teleki , who subsequently wrote for the Washington Post that he had never seen such a badly maintained laboratory. Psychologist Donald Barnes wrote in the same article that it was a “miserable and unhealthy environment for the monkeys” and a health hazard for humans. A resident vet, Richard Weizman, agreed that the lab was very neglected, but said the monkeys were well fed and were in "fair health."

Pacheco then reported the situation to the Montgomery Police Department and obtained a raid on the Maryland Animal Welfare Act on September 11, 1981. PETA issued appropriate information to the press in advance, so that the raid was accompanied by journalists and camera teams, much to the irritation of the officers. The police later testified that the monkeys lived in filthy circumstances. Richard Sawin, who led the raid, told the Washington Post in 1991: “It was just filthy and incredibly filthy in a way I've never seen it before. I've already done many searches. I've been involved in homicides, the drug scene, and pimping cases, but that was the first time that I was seriously concerned about my own health just because I was in this room. ”Subsequently, deaf because of 17 times Accused of cruelty to animals.

Police took the monkeys to the basement of a house owned by Lori Kenealy from the local Humane Society . Peter Carlson described in the Washington Post that the monkeys had toys, combed their toothbrushes with activists, received 24-hour care, and watched soap operas on television during the day . Taub's lawyers went to court and demanded that the monkeys be returned to him. Ten days after the raid, a judge granted the motion. But the monkeys were, as Carlson writes, "gone" in the meantime. Kenealy wasn't home at the time of the disappearance and stated that he knew nothing. Sawin then arrested her and locked her up. PETA activists were then told that without the monkeys as "evidence" deaf would not be prosecuted. A few days later the monkeys reappeared and, after brief negotiations, were handed over to the police. Under an order from Judge J. Cahoon, the monkeys were handed over to Taub, which sparked a public scene. During this time, a monkey, Charlie, died of what Taub called a "heart attack" and what Francione described as "dubious circumstances". A police investigation into the cause of death was unsuccessful because several organs had been removed from the body.

Taub publicly expressed anger over the matter. He claimed the lab was clean before he left for vacation. Pacheco failed to keep the cages clean and to care for the animals in order to publicly expose the laboratory on a false basis. During Taub's two-and-a-half week vacation, both carers did not come to work on seven days when the cages were to be cleaned. The statistical probability of such an event, based on previous records of the presence of the two, is 7 in a billion. On three of these days, there is evidence that Pacheco organized people to look after the monkeys. Taub's assistant and graduate student John Kunz said the carers took advantage of Taub's vacation to have some free time.

During the trial in October and November 1981, Taub testified in court that the monkeys had been treated "carefully" and were "in remarkable health." He acknowledged that the animals had not been vet examined for two years because he was himself an expert in treating monkeys. In response to the documentation showing open wounds and neglected bandages on the animals, he testified that treating the wounds would pose more risks to the animals. A treatment arouses the animals' interest in the parts of the body that they could not actually feel. This would cause further injuries to themselves. Bandages are sometimes necessary to prevent uncontrolled spreading or inflammation of the wounds, and it was often better to leave the bandages neglected than to change them. Taub also stated that Pacheco had put some photographs to create a dramatic effect. Some photos showed the monkeys in positions that were not part of his research. Pacheco denied this allegation, and PETA successfully sued the Washington Post for injunctive relief over an article containing the allegation. Another lawsuit against the scientist Peter Gerome was settled out of court on secret terms.

Regarding the dirt, Taub said, "A monkey room is a dirty place." It is normal for feces to lie on the floor in an animal testing laboratory and for food to fall into it. His employees cleaned the laboratory with mops and brooms almost every day. The monkeys were given fresh fruit daily, and he contradicted the prosecution's veterinary reports that the monkey woman Sarah was underweight.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), which funded Taub's research, suspended outstanding payments of $ 115,000. They started their own investigations and asked the Office for the Protection from Research Risks (OPRR) to examine Taub's laboratory. The OPRR then stated that animal care had been poor and identified a significant health risk. Based on this report, the NIH suspended the remaining $ 200,000 in outstanding payments, citing a violation of animal welfare standards. William Raub and Joe Held, as employees of the NIH, wrote in the Neuroscience Newsletter 1983 that deafferented monkeys, which the NIH had kept in its own laboratories since May 1981 and subjected to the same experiments, had no comparable lesions . They went on to write: "On the basis of these observations, it seems to us that fractures, dislocations, punctures, bruises, abrasions with subsequent infection, acute and chronic inflammations and necrosis are not an inevitable consequence of deafferentations."

After the appeal hearing, 67 professional associations publicly campaigned for Taub, and the NIH reversed its decision not to fund his research. In 1991, in response to the PETA film documenting the University of Pennsylvania's wound research , David Hubel stated , referring to the Silver Spring monkeys, that the research made scientific sense and that the people involved were not cruel. At the time of the Silver Jumping Monkeys, there were “only lax standards” that cannot be compared with the current situation.

Legal proceedings

In retrospect, Gary L. Francione , who represented PETA in several legal proceedings, found the cases very instructive in relation to the US animal rights movement and the legal structures that the movement was confronted with.

First trial (October 1981)

According to Peter Carlson's reports, pretty much every aspect of the first trial in 1981 was controversial and the referees on both sides disagreed heavily. The prosecution said Taub's laboratories were dirty and a health hazard. To do this, they cited police reports and witness statements. Taub argued that the laboratory was hardly dirtier than others. He also brought in police reports and witnesses who confirmed this point of view. Prosecution veterinarians said Taub's failure to bandage the animals' wounds "unnecessarily endangered" their health. Defense vets, including two who had done the same experiments at other facilities, said a bandage caused the monkeys to attack their own parts of the body. The court was also presented with 70 photographs of which laboratory staff said they had never seen the building in this state. Judge Stanley Klavan found Taub guilty of six animal cruelty. In the other 11 allegations, he acquitted Taub and fined $ 3,000. Deaf's assistant, John Kunz, was found guilty in all 17 cases.

Second trial and appeal hearing (1982 and 1983)

After a second hearing in June 1982, Taub was acquitted on another 5 cases by a jury at the Montgomery County Circuit Court. The jury upheld the conviction in the case of the monkey Nero, whose arm had to be amputated because of the injuries. Taub's remaining fine was $ 500.

This judgment was overturned in the appeal. The court followed an argument that the defending lawyers had not presented themselves, but only verbally noted. Francione commented on this approach as extremely unusual. According to the court, the Maryland Animal Welfare Act is not applicable. On the one hand, it did not contain an explicit exception for animal experiments. On the other hand, it only affects those suffering that are “unnecessary” or “unjustifiable”. The court argued in the judgment that the legislature must have known about the circumstances of vivisection , and elsewhere in the law it is noted that the infliction of suffering in vivisection is "incidental and inevitable". As a result, an amendment to the Maryland Animal Welfare Act was passed by the legislature, which explicitly includes laboratory animals. Maryland was the only state with such a policy. A few states explicitly exclude vivisection as the scope of the Anti Cruelty Statutes . Most make no statement about this.

Dispute over the care of the monkeys

What initially looked like the case was closed turned into a lengthy legal battle over the care of the monkeys in the following years.

Initially, two associations filed lawsuits to oblige the United State Department for Agriculture (USDA) and the NIH to enforce the nationwide animal welfare law in the case of the deaf: the Humane Society of the United States v. State and the Fall Fund for Animals v. Malone . Both lawsuits were dismissed on the grounds that individuals had no control over the executive powers of the USDA and the NIH.

Shortly after the ruling on the Maryland Animal Welfare Act criminal case, PETA and other societies called the civil courts to seek ownership of the monkeys. The case in the State Court of Maryland was relatively quickly referred to the Federal Court . There the lawsuit was dismissed because the organizations had no standing and were not directly affected. The clubs then called the United States Court of Appeals (4th circuit). This court also denied standing, on the grounds that "[t] he voluntary efforts cannot justify their own interest in the monkeys, which remain the property of the IBR and the care of the Maryland police." A personal interest of the associations in a "civilized and humane treatment" of the monkeys is analogous to the decision in the Sierra Club v. Morton not given. The associations 'third argument, that activists' personal relationship with the monkeys would be destroyed if they returned to the IBR, was rejected on the grounds that “unlike the Sierra Club case, the plaintiffs would not be able to visit the monkeys if the IBR were to do so will be forced to adhere to all laws. "

Contrary to promises by the authorities, the monkeys had since been handed over to Taub, who handed them over to the NIH. The NIH was under a lot of political pressure and there was little willingness among research centers to bring a “political bomb” into their homes. Finally, in June 1986, the monkeys were taken to the Tulane National Primate Research Center in Covington Louisiana (part of the NIH), where they continued to be owned by Taub. In a statement to Congress , the center said it had the welfare of the monkeys in mind, as they would have the opportunity to live outdoors and "enjoy the mild Louisiana climate". It acknowledges that the monkeys have "made their contribution to the research" and it is also "unaware of any planned invasive experiments for which these animals would be suitable". The operators of the protected areas Moorpark College ( California ) and Primarily Primates ( Texas ) offered in advance to take the monkeys in permanently, which was rejected by the NIH. The NIH argued that Taub or the IBR owned it, and the IBR refused to negotiate with the activists on grounds of principle. The IBR tried to surrender the property rights to the NIH (so that they could give away the monkeys in their place), but the NIH refused.

A group of researchers led by Mortimer Mishkin (NIH) was interested in the changes in the brains of the remaining monkeys. They argued that because of the political circumstances, their condition was unique in the world. Taub's original experimental plan would have planned to kill the monkeys long ago. But now you have a group of animals that have lived with deafferented body parts for decades and were sometimes treated with holding devices. Mishkin was a member of the board that decided whether or not to approve Taub's funds. He was the only one to vote against the decision to suspend payments to Taub after the raid. The experiment should be funded by the lobby organization Biomedical Research Defend Fund .

PETA obtained an injunction in Louisiana State Court that prohibited the trials. The NIH relied on 28 USC § 1442 (a) (1) (1988) and reversed the injunction. The dispute went again through several instances up to the Supreme Court, which dismissed the complaint because of lack of standing. The experiments on Augustus, Domitian and Big Boy in mid-1990 and on Allen and Titus in August 1991 then showed that the cerebral cortex of the deafferented animals had changed “massively” compared to healthy animals. The models prevailing at the time could not explain this reorganization and had to be reconsidered.

literature

- Deborah Blum: The Monkey Wars . Oxford University Press, USA, December 14, 1995, ISBN 978-0-19-510109-6 . ( Pulitzer Prize 1992)

- Alex Pacheco, Anna Francione: The Silver Spring Monkeys . In: In Defense of Animals 1985, ISBN 1-4051-1941-1 , pp. 135-147 (accessed March 13, 2011).

- Harold D. Guither: Appendix: Chronology of the Silver Spring Monkeys . In: Animal rights: history and scope of a radical social movement . SIU Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-8093-2199-5 .

- Some papers from Taub

- E. Taub, J. E Crago, L. D Burgio, T. E Groomes, E. W Cook, others: An operant approach to rehabilitation medicine: overcoming learned nonuse by shaping. . In: Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior . 61, No. 2, 1994, p. 281.

- E. Taub, G. Uswatte, R. Pidikiti, others: Constraint-induced movement therapy: a new family of techniques with broad application to physical rehabilitation-a clinical review . In: Journal of rehabilitation research and development . 36, No. 3, 1999, ISSN 0742-3241 , pp. 237-251.

- E. Taub, G. Uswatte, T. Elbert: New treatments in neurorehabiliation founded on basic research . In: Nature Reviews Neuroscience . 3, No. 3, 2002, ISSN 1471-003X , pp. 228-236.

Individual evidence

- ^ What Animals Want: Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy . Oxford University Press , 2004, p. 76, figure 4.2

- ^ Norman Doidge: The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science , 1st Edition, Viking Adult, March 15, 2007, ISBN 0-670-03830-X , p. 136.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Deborah Blum: The Monkey Wars . Oxford University Press, USA, December 14, 1995, ISBN 978-0-19-510109-6 , pp. 105-133.

- ^ Norman Doidge: The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science , 1st edition, Viking Adult, March 15, 2007, ISBN 0-670-03830-X , p. 141.

- ^ Ingrid Newkirk: Free the animals: the amazing true story of the Animal Liberation Front . Lantern Books, October 2000, ISBN 978-1-930051-22-5 , pp. 1 ff.

- ^ Edward Taub - Psychology - UAB College of Arts and Sciences | UAB. Retrieved November 18, 2019 (UK English).

- ↑ Dr. Edward Taub ( Memento of March 8, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Jeffrey M. Schwartz, Sharon Begley: The Mind and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force . Harper Perennial, October 1, 2003, ISBN 978-0-06-098847-0 .

-

^ Norman Doidge: The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science , 1st edition, Viking Adult, March 15, 2007, ISBN 0-670-03830-X , pp. 139 & 141.

- E. Taub, J. E Crago, L. D Burgio, T. E Groomes, E. W Cook, others: An operant approach to rehabilitation medicine: overcoming learned nonuse by shaping. . In: Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior . 61, No. 2, 1994, p. 281.

- ↑ a b c edited statement by Pacheco with pictures. (www.petatv.com)

- ^ AS Clarke: 'Silver Spring' Monkeys at the San Diego Zoo . In: Laboratory Primate Newsletter . 27, No. 3, July 1988. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ A b c d Peter Carlson: The Strange Case of the Silver Spring Monkeys . In: The Washington Post Magazine , February 24, 1991.

- ^ A b c d e f g h i G. L Francione: Animals, Property, and the Law . Temple Univ Press, 1995, ISBN 1-56639-284-5 , pp. 72-90.

- ↑ Alex Pacheco, Anna Francione: "The Monkeys of Silver Spring". In: Peter Singer (Ed.): "Defend the animals - considerations for a new humanity". Paul Neff Verlag, Vienna 1986, ISBN 3-7014-0225-6 , pp. 207-208.

- ^ A b Alex Pacheco, Anna Francione: The Silver Spring Monkeys . In: In Defense of Animals 1985, ISBN 1-4051-1941-1 , pp. 135-147 (accessed March 13, 2011).

- ↑ a b c d David Michael Ettlin: Taub denies allegations of cruelty . In: Baltimore Sun , November 1, 1981. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ↑ Alex Pacheco, Anna Francione: The Silver Spring Monkeys . In: In Defense of Animals 1985, ISBN 1-4051-1941-1 , pp. 135-147 (accessed March 13, 2011).

- ↑ L. Falkin: Taub v. State: Are State Anti-Cruelty Statutes Sleeping Giants . In: Pace Environmental Law Review . 2, 1984, p. 255.

- ↑ Kathy Snow Guillermo: Monkey Business: The Disturbing Case That Launched the Animal Rights Movement , 1st Edition / 1st Printing. Edition, National Press Books, September 1993, ISBN 1-882605-04-7 , p. 143. , refers to an exchange of letters between William Raub (NIH) and Joseph Vasapoli (IBR)

- ↑ Kathy Snow Guillermo: Monkey Business: The Disturbing Case That Launched the Animal Rights Movement , 1st Edition / 1st Printing. Edition, National Press Books, September 1993, ISBN 1-882605-04-7 .

- ↑ T. P Pons, P. E Garraghty, A. K Ommaya, J. H Kaas, E. Taub, M. Mishkin: Massive cortical reorganization after sensory deafferentation in adult macaques . In: Science . 252, No. 5014, 1991, ISSN 0036-8075 , p. 1857.

Remarks

- ^ First, Institute for Behavioral Research . In the meantime it has been renamed the Institute for Behavioral Resources .

- ↑ The concept of and the debate about standing is in some cases comparable with the Federal German collective right of action or the Swiss right of association complaint .

- ↑ The relevant core statement of the judgment here is that associations cannot represent interests in court, but that this representation must be carried out by affected persons themselves.

- ↑ At that time Delta Primate Center