Brown rat

| Brown rats | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Brown Rat ( Rattus norvegicus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Rattus norvegicus | ||||||||||||

| ( Berkenhout , 1769) |

The brown rat ( Rattus norvegicus ) is a rodent (Rodentia) belonging to the long-tailed mouse family . The species, originally native to northern East Asia, was distributed worldwide by humans and is now found on all continents except Antarctica and on almost all larger islands or archipelagos. Brown rats inhabit forests and bushy terrain in their original area. Introduced populations, however, are predominantly restricted to human settlement, and in warmer climates the species is only found in the most heavily modified habitats and mostly only near the coast. Brown rats are omnivores , with vegetable food mostly predominating.

The species is often controlled as a food pest, disease carrier and problematic neozoon . The brown rat is the wild ancestral form of the color rat , which is kept in large numbers as pets and laboratory animals.

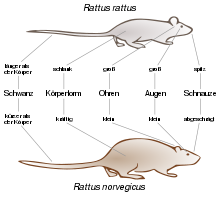

description

Brown rats are large, strongly built rats with a square skull, blunt snout and thick tail, the length of which is usually less than the head-trunk length . The head-trunk length is 18-26 cm, the tail length 14-21 cm and the length of the hind foot 38-45 mm. The tail has 163–205 scale rings. The ears are round and small with a length of 17–23 mm; when folded forward, they maximally reach the rear edge of the eye. Sexually mature animals weigh about 170-350 g.

The species shows marked sexual dimorphism , males are larger and heavier than females. In a sample from Görlitz, males in two age groups of sexually mature animals weighed an average of 309 and 404 g, females in the same age groups 255 and 315 g. Males were on average 17.5 and 22% heavier than females, the head-torso length of the males was 8.1 and 10.1% longer.

The fur is dirty gray-brown, reddish brown-gray to dark brown-black, the underside gray-white. Upper and lower side coloring are not clearly separated. Monochrome black animals are rare. The tail is two-colored, gray-brown on top and lighter on the underside.

The youth dress, which was developed at the age of about five weeks, is a single color, matt brown-gray on the top, and dark gray on the belly. During the following hair changes, the animals become increasingly lighter and the yellow and red pigmentation of the hair increases. When reaching sexual maturity with a head-trunk length of about 200 mm, the back can be fox-red. With further hair changes, the black at the ends of the hair becomes more extended and the fur becomes darker as a result, it is then finally brown-black.

Systematics

The brown rat was scientifically described by John Berkenhout as Mus norvegicus in 1769 . Why he chose " norvegicus " as the specific epithet is unclear, Berkenhout does not provide any information.

Wilson and Reeder do not recognize any subspecies for the brown rat. The systematic position of the species within the genus Rattus , as well as the systematics of the entire genus, is still unclear today. Traditionally, the brown rat was placed in a subgenus Rattus with the house rat and some other species . Wilson and Reeder reject this assignment due to clear morphological , blood chemistry and genetic differences between the common rat and the house rat. Due to the large morphological variation, the authors assume the existence of several monophyletic groups within the genus Rattus , which must show whether these can really only be assigned to one genus. They therefore place the brown rat in a " Rattus norvegicus species group" for the time being, to which they add the Himalayan rat ( Rattus nitidus ) and the Central Asian rat ( Rattus pyctoris ) based on molecular genetic data and some morphological similarities .

Karyotype and genome

The brown rat has 2n = 42 chromosomes , two of which are sex chromosomes . The complete genome consists of approximately 2.75 billion base pairs .

distribution

The brown rat was originally native to temperate, northern East Asia. The area with probably autochthonous occurrences includes the southeast of Siberia , the northeast of China and the Japanese islands of Honshū , Shikoku and Kyūshū . It is not known when the spread to the west began. Europe was likely reached via Russia in the 18th century. Bone finds from Schleswig-Holstein , which were formerly dated to the 9th to 10th and 13th to 14th centuries, are now regarded as being carried over into deeper soil layers. The worldwide unintentional naturalization took place mainly by ship. The British Isles were also settled in the 18th century . The first records from America date back to 1745, the main settlement of North America took place as ship rats with the great wave of British immigration between 1760 and 1780. Today the species occurs on all continents except Antarctica and on almost all larger islands or archipelagos on earth.

Brown rats are now native to all European countries. In Central and Northern Europe, the distribution is largely extensive, only in areas sparsely populated by humans such as parts of Scandinavia and Finland are the occurrences sporadically and locally narrowly limited. In the Mediterranean , the settlement is much less coverage and draws particular attention to the Iberian Peninsula and in the Balkan large gaps.

habitat

In their original area in Northeast Asia, brown rats inhabit forests and bush-rich terrain. However, introduced populations are predominantly restricted to the human settlement area and inhabit sewers, landfills, cellars, warehouses, stables, farms and similar habitats, very often near water. In addition, the species also inhabits near-natural habitats in Europe, especially the edges of water bodies with dense vegetation and sea coasts, especially in the area of estuaries. In warmer climates and especially in the tropics, the species is only found in habitats that have been most heavily modified by humans, such as sewers, buildings, breakwaters, ports and large cities, and mostly only near the coast. In West and South Africa, for example, as well as in Australia, the species is restricted to seaports and large coastal cities and only populates inland cities only in exceptional cases.

food

Brown rats are omnivores, with vegetable food mostly predominating. Of the 4,000 stomachs of German brown rats examined in the late 1940s, 39% contained only different types of grain, and a further 34% only contained fresh parts of plants such as fruits, vegetables and grasses. In 11% of the stomachs there were both vegetable and animal components, in 10% only meat or fish. Even in trap attempts, baits rich in carbohydrates such as oatmeal were clearly preferred over baits made from vegetables, meat or fish.

In Europe the brown rat lives mainly commensally on human food, but a wide range of other plant and animal food sources are also used. The animals climb trees to eat buds and young shoots in spring and fruit and walnuts in late summer . The diet is also carnivorous and predatory, brown rats eat, among other things, bird eggs, young and weakened birds, young and adult voles , amphibians and mollusks .

Way of life

Activity and Build

The brown rat is crepuscular and nocturnal under undisturbed conditions with maximum activity shortly after sunset and shortly before sunrise; activity is low at midnight. This basic activity pattern can be varied in many ways depending on the external conditions. Brown rats living in office or storage rooms shift their activity in times of human absence; in a study in England brown rats were almost exclusively diurnal in summer on one of five farms examined, as this farm was very often visited by foxes at night .

The animals swim, dive and climb well. However, locomotion takes place mainly on established paths on the ground, in buildings mostly along walls, to which the animals keep contact with the vibrissae from the side . In rocky areas, brown rats usually run on the bottom of crevices.

If possible, brown rats build earthworks that have at least two entrances and a living boiler and often also pantries. The entrances are always open, the main corridors are transversely oval, 8–9 cm high and 11–12 cm wide. In buildings the nests are built in hiding places of all kinds, e.g. B. between stacks of goods, in double walls, under floorboards or under piles of straw. The nests are made of grass, leaves, paper and similar soft material.

Social behavior

The social organization of a local population is primarily dependent on the food supply. In habitats with a small or widely distributed food supply, individual males occupy territories that in turn include the territories of several females. In areas with a high and in a few places concentrated food supply, for example at rubbish tips, brown rats live in groups of many females and many males (“clans”), which presumably defend their territory against other clans.

Within a clan, the males form an almost linear hierarchy that is established through frequent fights. The social status of a male depends primarily on his age. Larger males have a good chance of winning a fight against smaller males, especially if they are strange. The position once established in relation to a certain male is usually retained later, although lower-standing males can then be physically equal or even superior to the higher-positioned males. In stable clans, age is therefore a better indicator of a male's social status than height.

Reproduction and Age

Brown rats living in clans are largely promiscuous due to the mating system . The females are usually only oestrus (ready to conceive) for one night . During this time they are followed by several males, usually two to three, up to a maximum of seven. The males constantly try to copulate with the female, pushing other males aside. This “ scramble competition ” is so intense that the males largely forego fighting with one another, which is why even males in the lower ranking succeed in copulating with the female. In an experimental study that gave Estonian females the opportunity to choose between different males without being exposed to the jostling competition, the females formed a close bond with a particular male. However, these females were still promiscuous and also copulated with a selection of other males, but to a lesser extent than under normal conditions.

Reproduction takes place all year round in Europe, in Berlin maxima were found in March and in September and October, in England in May and October. The gestation period is 22-24 days. The litters in bred brown rats comprised 1–15, mostly 4–8 young. In small towns in Lower Saxony, an average of almost 5 embryos were found in females living in the sewer system, whereas an average of almost 7 embryos were found in those living above ground. Brown rats are naked at birth, eyes and ears are closed. The ears open after three days, hair begins to grow after 10 days, and the eyes open by around 15 days of age. After about 20 days the young animals explore the area around the nest and after 25–30 days also the area around the den. They are suckled for about 40 days. Sexual maturity is reached between three and four months of age. In captivity, reproduction in females declines sharply at the age of 19 months and the maximum lifespan is around three years.

Natural enemies

The brown rat is one of the food of numerous predators , especially among the predatory mammals , hawks and owls . In Europe, the species is often captured by various martens such as stone marten, polecat , ermine and the introduced mink . Even dogs and occasionally cats can hunt brown rats. Among the owls, the eagle owl in particular eats brown rats to a considerable extent, during the breeding season the proportion of the brown rat in the eagle owl's food spectrum can reach 30%. Snakes are also one of the regulators of the population of these mammals worldwide.

Harmful effects

Food and hygiene damage

In Europe, the species is primarily a food and hygiene pest . Damage occurs when food is eaten, but above all when it is contaminated with faeces and urine and when packaging materials are destroyed. Hygiene problems arise primarily from the spread of paratyphoid germs in kitchens and pantries, which is a common cause of food and feed poisoning.

Disease transmission

Brown rats are mainly known in Europe as a reservoir and secretor of leptospira, the causative agent of leptospirosis . The brown rat is the host of the rat flea ( Xenopsylla cheopis ) and other flea species and can therefore act as a reservoir for Yersinia pestis , the pathogen causing the plague . In the great plague pandemic of the late Middle Ages , the brown rat did not play a major role, at least in Europe, at that time it did not occur in Europe. On the other hand, together with the house rat, it is regarded as the main reservoir of the plague pandemic that began in China in the mid-19th century and killed around 12 million people worldwide, especially in India . Today the two rat species are only considered to be an important reservoir for the plague pathogen in a few regions of the world, including Madagascar , India and the Democratic Republic of the Congo .

Role as a neozoon

The worldwide naturalization of the brown rat by humans often had considerable negative effects on the flora and fauna, especially on islands. Overall, however, the negative influence was or is probably significantly lower than that of the domestic rat, which is also naturalized worldwide, among other things because the brown rat was not able to establish itself much more poorly, especially in the tropics, and is often tied to human settlements or to open fresh water.

Massive impacts have been documented especially for small islands that were originally mammal-free in temperate and arctic climates, especially around New Zealand . On the main islands of New Zealand, the brown rat, in contrast to the house rat, does not play an ecological role due to its very local distribution. On numerous offshore islands, however, the effects are considerable, and on many of these islands the brown rat has been wiped out again as part of targeted campaigns. On the 170 hectare Breaksea Island, for example, after the brown rat was exterminated in 1986, a significant increase in seedlings was found in 19 of 24 tree and shrub species. Natural rejuvenation was observed for pseudo-beeches ( Nothofagus ssp.) After an interruption of about 100 years . Skinks colonized the island from neighboring rocky islands, and two endangered weevils and the saddle bird ( Philesturnus carunculatus ) were successfully reintroduced.

On Whale Island (240 ha), brown rats reduced the breeding success of the long-winged petrel ( Pterodroma macroptera ) in the 1960s and early 1970s by eating eggs and young or weakened chicks by 19–35%. After the number of wild rabbits, naturalized in 1968, had risen sharply, which subsequently enabled the brown rat to increase significantly, the breeding success fell from 1972 to 1977 to almost zero. After the extinction of brown rats and wild rabbits in 1987, the breeding success rose steadily again.

Campbell Island , about 700 km south of New Zealand's main islands, is 112.7 km² in size and until 2001 was home to the densest brown rat population in the world. The population was estimated at around 200,000 individuals. The flightless Campbell Duck ( Anas nesiotis ) was probably exterminated on the island by the brown rat. It was thought to be extinct in the meantime and was only rediscovered in the mid-1970s on the neighboring 26-hectare Dent Island . After the brown rat was eradicated on Campbell Island in 2003, the Campbell Duck was successfully resettled there.

Existence and endangerment

The brown rat is one of the most common mammal species in the world, the population is apparently largely stable. The species is not endangered worldwide.

Domestication

The brown rat is the wild ancestral form of the color rat , which is kept in large numbers as pets and laboratory animals. Results of the first breeding experiments with albinos and wild brown rats were published between 1877 and 1885. Shortly before 1900, albinos were already being used by various scientists as experimental animals in psychology . After that, the color or laboratory rat developed into the most common laboratory animal in biology and medicine after the house mouse . By the end of the 1970s, around 100 inbred strains were known. Compared to the wild form, the color rat's brain volume is about 8% smaller, but the reduction affects the different brain areas to different degrees. For example, in accordance with the pet rat's reduced urge to move, the areas of the brain that control the motor function of the corpus striatum and cerebellum are particularly greatly reduced; the olfactory centers, on the other hand, are much less regressed.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Brown Rat - Rattus norvegicus. In: kleinsaeuger.at. Accessed July 31, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d S. Aulagnier, P. Haffner, AJ Mitchell-Jones, F. Moutou, J. Zima: The mammals of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East - The destination guide. Haupt Verlag, Bern / Stuttgart / Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-258-07506-8 , pp. 236-237.

- ↑ a b c d e E. Stresemann (short), K. Senglaub (ed.): Excursion fauna of Germany. Volume 3: Vertebrates. 12th edition. 1995, ISBN 3-334-60951-0 , pp. 415-416.

- ↑ a b c K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Volume 1: Rodentia I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, p. 401.

- ↑ a b A. Dietze, O. Zinke, H. Ansorge: Study on the reproduction and morphology of the brown rat Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - A contribution to the fauna of Upper Lusatia. In: Publ. Mus. West Lusatia Kamenz. 26, 2006, pp. 117-128.

- ^ K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Volume 1: Rodentia I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, p. 408.

- ^ John Berkenhout: Outlines of the Natural History of Great Britain and Ireland. Volume 1, 1769, p. 5. (digitized, online)

- ↑ a b c d Rattus norvegicus. In: DE Wilson, DM Reeder: Mammal Species of the World . Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4 . ( online ( Memento from June 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Rattus. In: DE Wilson, DM Reeder: Mammal Species of the World . Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4 Online ( June 7, 2010 memento on the Internet Archive )

- ^ RA Gibbs, GM Weinstock, ML Metzker et al: Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution . In: Nature . tape 428 , no. 6982 , April 2004, p. 493-521 , doi : 10.1038 / nature02426 , PMID 15057822 .

- ↑ State Office for Nature and Environment of the State of Schleswig-Holstein: The Mammals Schleswig-Holstein - Red List. Kiel 2001, ISBN 3-923339-65-8 , p. 33 online (PDF; 354 kB).

- ↑ AJ Mitchell-Jones, G. Amori, W. Bogdanowicz, B. Krystufek, PJH Reijnders, F. Spitzenberger, M. Stubbe, JBM Thissen, V. Vohralik, J. Zima: The Atlas of European Mammals. Poyser, London 1999, ISBN 0-85661-130-1 , pp. 278-279.

- ↑ a b c d K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Volume 1: Rodentia I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, pp. 409-410.

- ↑ a b c d K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Volume 1: Rodentia I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, pp. 413-415.

- ^ David W. Macdonald, Fiona Mathews, Manuel Berdoy: The Behavior and Ecology of Rattus norvegicus: from Opportunism to Kamikaze Tendencies. In: G. Singleton, L. Hinds, H. Leirs, Z. Zhang (Eds.): Ecologically-based rodent management. Australian Center for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia 1999, pp. 49-80, here pp. 59-60.

- ↑ a b c d e John Innes: Advances in New Zealand mammalogy 1990-2000: European rats. In: Journal of The Royal Society of New Zealand. 31, Issue 1, 2001, pp. 111-125.

- ^ David W. Macdonald, Fiona Mathews, Manuel Berdoy: The Behavior and Ecology of Rattus norvegicus: from Opportunism to Kamikaze Tendencies. In: G. Singleton, L. Hinds, H. Leirs, Z. Zhang (Eds.): Ecologically-based rodent management. Australian Center for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia 1999, pp. 49-80, here pp. 54-55.

- ↑ a b David W. Macdonald, Fiona Mathews, Manuel Berdoy: The Behavior and Ecology of Rattus norvegicus: from Opportunism to Kamikaze Tendencies. In: G. Singleton, L. Hinds, H. Leirs, Z. Zhang (Eds.): Ecologically-based rodent management. Australian Center for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia 1999, pp. 49-80, here pp. 55-57.

- ↑ a b K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Volume 1: Rodentia I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, p. 412.

- ↑ József Lanszki, Bertalan Sárdi, Gabriella L. Széles: Feeding habits of the stone marten (Martes foina) in villages and farms in Hungary. In: Natura Somogyiensis. 15, 2009, pp. 231-246.

- ↑ M. Stubbe: Mustela vison Schreber 1777 - Mink, American mink. In: M. Stubbe, F. Krapp (Ed.): Handbook of Mammals in Europe. Volume 5: Predatory mammals - Carnivora (Fissipedia), Part II: Mustelidae 2. Viverridae, Herpestidae, Felidae. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 654–698, here pp. 680–682.

- ↑ Eckhard Grimmberger: The Mammals of Germany. Observe and determine. Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelshofen 2014, p. 330.

- ↑ Lutz Dalbeck: Food as a limiting factor for the eagle owl Bubo bubo (L.) in the Eifel? In: OrnithPopol. Number 44, 2005, pp. 99-112.

- ↑ a b K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Volume 1: Rodentia I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, p. 415.

- ↑ Matthias Niederig, Barbara Reinhardt, Gerd-Dieter Burchard, Herbert Schmitz, Egbert Tannich, Kathrin Tintelnot, Gabriele Laude, Katharina Alpers, Klaus Stark, Jens Mehlhose: Profiles of rare and imported infectious diseases. Robert Koch Institute, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89606-095-3 , pp. 73-74.

- ^ Sarah E. Rollins, Sean M. Rollins, Edward T. Ryan: Yersinia pestis and the Plague. In: Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 119 (Suppl. 1), 2003, pp. 78-85. ( Online as PDF ( Memento from April 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Global Invasive Species Database: Rattus norvegicus (mammal) - Impact Info. ( online ; accessed February 22, 2011)

- ^ P. McClelland, H. Gummer: Reintroduction of the critically endangered Campbell Island teal Anas nesiotis to Campbell Island, New Zealand. In: Conservation Evidence . 3, 2006, pp. 61-63. (on-line)

- ↑ Rattus norvegicus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2016 Posted by: AR Ruedas, 2016. Accessed July 31 of 2019.

- ^ K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Volume 1: Rodentia I. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, pp. 415-416.

literature

- K. Becker: Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) - brown rat. In: J. Niethammer, F. Krapp: Handbook of mammals in Europe. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1978, pp. 401-420.

- DW Macdonald , F. Mathews, M. Berdoy: The Behavior and Ecology of Rattus norvegicus: from Opportunism to Kamikaze Tendencies. In: G. Singleton, L. Hinds, H. Leirs, Z. Zhang (Eds.): Ecologically-based rodent management. Australian Center for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia 1999, pp. 49-80.

- Rattus norvegicus. In: DE Wilson, DM Reeder: Mammal Species of the World . Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4 . on-line

Web links

- Rattus norvegicus - entry in GenBank

- German Pest Links Fighters Association eV