Panchatantra

The Panchatantra ( Sanskrit , n., पञ्चतन्त्र, pañcatantra , [ pʌɲʧʌtʌntɽʌ ], lit .: "five tissues") is an ancient Indian poetry in five books. The shape we know today was created between the late 3rd and 6th centuries AD. It is a collection of moral stories, fables, and animal stories. They were used in the Indo-Iranian culture to educate the princes at court, to convey the art of administration and secular wisdom. The work was very well received in the Persian Sassanid Empire ; the first translations into Middle Persian were made in the 6th century.

Time of origin

According to recent research, the poetry originated around 300 AD, in the 6th century it was so well known that it was translated into Pahlavi . Around 570 AD the Pahlavi version was translated into Old Syrian . The fables reached Europe in the 13th century through Persian and Arabic translations. The Panchatantra was already known in the royal courts of Europe towards the end of the 15th century.

The Panchatantra is a combination of popular fable and political textbook. Proverbs teach both political wisdom and wisdom. However, the former predominate. “It has always remained, in its entirety, a work, the stated purpose of which was to teach in a pleasant way what the Indians Nitishastra (the science of leadership, the art of government and politics) and by another name also Arthashastra (the Science of Worldly Benefits) ”. What was new was the idea of teaching political knowledge (nīti) in an artistic form. The Tantrakhyayika is a work of Sanskrit art poetry. The prose is art prose and is characterized by long compounds. The popularity of the book is probably the reason for the many adaptations. The Panchatantra has been translated into more than 50 languages.

1st thesis: most of the material was drawn from popular literature (Jātakas) and transformed into better Sanskrit. The author “Visnusharman” probably also used older material, but reworked it freely and independently, he probably also invented new fables and stories.

One can doubt whether the last two books (IV, V) have survived in full. Books IV, V contain only general teachings on wisdom.

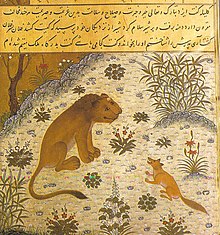

The animal stories usually contain a moral lesson. One book describes how a lion and a bull that has become free first make friends, but then fall for the intrigues of a jackal. The lion kills his new friend, the bull. The lesson is that not recognizing the enemy in the (alleged) friend can bring much misfortune.

Another book tells of a brahmin who has his baby guarded by a mongoose at home. The mongoose kills a snake that wants to attack the child. When the brahmin comes home, the mongoose jumps joyfully towards him. The brahmin only sees the bloody snout of the mongoose and kills the animal. At home he has to recognize his mistake. The lesson is that it can be fatal to be guided by current prejudices and fail to see who your real friends are.

State of research

The following paragraph describes the researchers who have studied the Panchatantra and what has been the subject of their investigation.

- Charles Wilkins (1786): He found out that the Hitopadesha is a later adaptation of the Panchatantra.

- Silvestre de Sacy (1816): Derived from the Pehlavi translation and Hitopadesha go back to a common Indian source.

- Theodor Benfey (1859): He translated the pancatantra and researched the Arabic reviews. He compared the fables from Arabic with parallels from India (hiking trails).

- Leo von Mankowski (1892): Comparison of pancatantra sections from Kṣemendras Bṛhatkathāmañjarī and Somadeva's Kathāsaritsāgara with the Panchatantra. Its result was that the Pehlavi translation drew on the pancatantra, Mahābhārata and Buddhist sources.

-

Johannes Hertel (1908 to 1915): Publication of the critical edition of Tantrākhyāyika, based on fragmentary manuscripts. Comparison of over 90 manuscripts, which he classified into 5 groups. His thesis was that all reviews go back to a common archetype. The question was: how did the author of the Pancatantra use his drafts and what was the intention of making changes? Hertel's opinion: Pancatantra is a work to simplify the study of the princes, the art of politics (sansk. Nīti ) and at the same time to learn good Sanskrit. He divided the 5 groups as follows.

- The Tantrākhyāyika with 2 sub-reviews. The oldest version is the Tantrākhyāyika, which has been preserved in an older and a more recent review in Kashmir. There is also a very extended Sanskrit text from the "southern pancatantra". Many new narratives have been added to this text, which come from various Panchatantra versions and also from Tamil sources. Most of the stories come from popular literature.

- An abbreviated north-western manuscript (south pancatantra, Nepalese verse review, Hitopadeśa). This goes back to an extract made in northwest India, which was made after the 7th century AD. Tantrākhyāna preserved in Nepal shows points of contact both with the Jaina arrangements, especially that of the Pūrṇabhadra, and with the southern pancatantra ("textus amplior"). There are 3 reviews of it. The third of these is in Nepalese language. This compilation should belong to the 14th century. The most important revision is the Hitopadeśa. This is a completely new work, where the author mentions in the preface that his work is based on the pancatantra.

- Pehlevi translation (Arabic, Syrian reviews). A text that was translated into Pehlevi (Middle Persian) around 570. The text is lost, but further translations into Arabic and Syriac have been made from the Pehlevi translation.

- Pancatantra sections of the Bhṛhatkathāmañjari of Kṣemendra, Kathāsaritsāgara of Somadeva.

- jinistic arrangements (textus simplicor and textus ornatior des Pūrṇabhadra) (a more recent arrangement of pancatantra). textus ornatior, d. i. the pancatantra which the Jaina monk Pūrṇabhadra completed at the behest of the minister Soma in 1199 is based on the textus simplicior. The “textus simplicior” is the version of the text that has been the longest and best known in Europe. It is a completely new adaptation of the old work of Tantrākhyāyika. Numerous new narratives have been added, including many new stanzas, while many of the stanzas in the old versions have been left out. The two versions edited by Jainas have found the greatest distribution in India. Numerous mixed reviews have emerged from it. One of these mixed texts is the Pañcākhyānoddhāra by the Jain monk Meghavijaya from 1659/60.

- Franklin Edgerton (1924): His thesis was that all 4 reviews go back to an original pancatantra. He groups the manuscripts into 4 groups. All are considered equally for the constitution of the basic work, from which he created the "Pancatantra Reconstructed". The 4 groups were divided as follows:

- Bhṛhatkathā (Somadeva, Kṣemendra)

- Ur-T: (Tantrākhyāyika and textus simplicor)

- Ur-Sp: (Hertels NW): southern pancatantra, Nepalese pancatantra, Hitopadeśa

- Ur-Pa (Syrian, Arabic version)

- A. Venkatasubbiah: His main focus was on a previously undiscovered version of 1015-1042 in Kannada language . His assumption: the source of the pancatantra can be found in the Bhṛhatkathā.

- Ruprecht Geib (1969): The Pancatantra is a book of wisdom and the art of governance. It is not enough to examine stylistic subtleties, but rather an interpretation of the text. He tried to generate a new family tree. He established three criteria for verifying the authenticity of fables. His result was that Hertel's family tree needed only minor changes and that Edgerton's family tree was wrong.

- Harry Falk (1978): He compared the material of the Tantrākhyāyika, Pāli-Jātakam and the Mahābhārata. The aim was to recognize the working method and the intention of the author of the Tantrākhyāyika in dealing with his templates. It is a matter of a philological text evaluation and interpretation in equal measure. He compares individual fables in parallel texts

The Panchatantra in World Literature

At the behest of the Sassanid king Chosrau I (531-579), a north-west Indian review along with other Indian texts was transferred by the doctor Burzooe to Pahlevi (Middle Persian written language). The translation has been lost, there are translations from Arabic and Syriac. The main value of the Pahlevi translation is that it was the starting point for the spread of pancatantra and its narrative content to the West.

In 570 a Syrian clergyman and writer translated the book from the Pahlevi into Syrian under the title Kalilag and Damnag . The translation is incomplete.

Around the year 750 there was an Arabic translation of Abdallah ibn al-Moqaffa with the title Kalīla wa Dimna (English: Lion King and Jackal). This Arabic translation became the source of numerous translations into European and Asian languages namely:

- around 10th to 11th centuries: probably another translation into Syrian from Arabic.

- Late 11th century: Symeon, son of Seth, translation from Arabic into Greek. Translations into Italian by Giulio Nuti (Ferrara 1583), two Latin, one German and several Slavic translations are based on this Greek text

- The Hebrew translation by Rabbi Joel from the beginning of the 12th century, which has only survived in a single incomplete manuscript, is of greatest importance. It was based on the following texts:

- A Latin translation of the Hebrew text by Johann von Capua under the title "Liber Kalilae et Dimnae, Directorium vitae humanae" between 1263 and 1278. In 1480 two printed editions of this text were published, based on poor handwriting.

- In the second half of the 15th century, Antonius von Pforr translated from Latin into German with the title “The book of examples of the old wise men”. For a long time this translation contributed to the knowledge of the work throughout Europe.

- a Spanish translation, which was printed in Saragossa in 1493, is based on the Latin text by Johannes von Capua, using Pforr's German translation

- The "Discorsi degli animali ragionanti tra loro" by Agnolo Firenzuola , which first appeared in 1548 and were translated into French in 1556, are an Italian free copy of this Spanish translation .

- In 1552 Antonio Doni's Italian translation appeared in two parts. The first part was written by Thomas North under the title “The Moral Philosophy of Doni. popularly known as The fables of Bidpai "(London 1570 and 1601) translated into English

- a second Hebrew translation from Arabic by Jacob ben Eleazar is from the 13th century. Only the first half of the work has survived.

- 1142: Persian translation with the title "Kitāb Kalīla wa Dimna" organized by Abu'l-Māalī Naṣrullāh ibn Muhammed ibn 'Abdul-Ḥamīd. Several Eastern Turkish translations and adaptations are based on this translation, as well as the Persian revision by Husain Wā'iz Kāšifī known under the name “Anwār-i Suhailī” (Eng. The lights of the star Canopus ). Kāšifī adapted the language to the complicated office language of the Timurid court of Herat and added many stories. This book became the source for numerous translations into European and Asian languages

- In Europe it became known through the French translation, known by David Sahid and Gaulmin under the title "Livre des lumières ou la Conduite des roys" first published in 1644 in Paris. and then translated into Swedish, German and English

- The book Anwār-i Suhailī found still further dissemination through the Turkish translation, which was made under the title Humāyūn Nāmeh, "the book of the emperors" by 'Alī-bin Ṣāliḥ' and dedicated to Sultan Suleyman I (1512-1520). Galland and Cardonne translated the book from Turkish into French and retranslated this French translation into German, Dutch, Hungarian and Malay.

- An old Spanish translation (around 1251) also emerged directly from the Arabic translation of “Kalīla and Dimna”. Raimundus de Biterris Liber de Dina et Kalila is based partly on this Spanish translation, partly on the Liber Kalilae et Dimnae by John of Capua .

- Most of the fables in “Novus Esopus” by the Italian Baldo, who wrote in the first half of the 12th century, also come from an unknown version of Kalīla and Dimna .

- Finally, two Malay books of fable are based partly on Kalīla and Dimna, partly on South Indian adaptations of the pancatantra, while other rear-Indian and island-Indian adaptations emerged directly from the pancatantra.

Criteria for determining interpolation

- Hertel has defined 4 criteria for interpolation:

- “All narratives that have nothing to do with cleverness or stupidity are suspect of interpolation.

- The interpolations go back to different times and different authors. In several cases - not in all - style is a safe criterion.

- The more or less clumsy type of insertion reveals the interpolator.

- Every narrative is suspect of an insert which is missing in one of the sources Pa., Som, N, Sar a, Sar b. On the other hand, the transmission of a narrative, even in all sources, still offers no reliable guarantee of its authenticity. "

- Edgerton's methodological approaches:

- - Criteria for the reconstruction of the Panchatantra Reconstructed:

- important commonalities (fables), from which one cannot assume that they belonged to the original text

- minor correspondence which, according to identification, does not go back to the original pancatantra in other versions

- common gaps

- - methodological principles for determining interpolation:

- Trains that are the same everywhere belong to the original

- Omissions in Hitopadeśa and Bhṛhatkathā are insignificant

- very small trains that belong to a small number of independent versions do not need to be original

- important features that belong in independent versions are the more likely original the closer they correspond

- Fables found in several independent versions are almost certainly real

- Common features in related reviews prove nothing for the originality

- Ruprecht Geib's methods for determining interpolation:

- A statement of a general kind can be understood separately from the frame narrative

- The switching fable explains a special event of the frame from the speaker's point of view

- the fables objectively reflect the speaker's situation and true intention

The content of the Panchatantra

I. Breaking up with friends

Frame story: lion and bull

- Monkey and wedge (ape and wedge)

- Jackal and drum

- The King's Merchant and King's Sweep

- Monk and swindler (3 self-wasted accidents?) (Monk and swindler)

- Ram and jackal (Rams and jackal)

- the cuckold weaver

- Crows and serpent

- Heron, fishes and crab

- Lion and hare

- the weaver as Vishnu (weaver as vishnu)

- grateful beasts and thankless man

- Louse and flea

- blue jackal

- Goose and owl

- Lion outwitting camel (lions retainers outwit camel)

- Lion and wheelwright

- the beach bird and sea

- 2 geese and tortoise

- 3 fishes

- the allies of the sparrows and the elephant (sparrow's allies and elephant)

- Goose and fowler

- Lion and ram

- Jackal outwits camel and lion (Der cunning jackal) (jackal outwits camel and lion)

- King, minister and false monk

- Girl marries a snake (maid weds a serpent)

- Gods powerless against death

- Girl marries a snake (maid weds a serpent)

- Monkey, glow-worm, and officious bird (ape, glow-worm, and officious bird)

- Good-heart and bad-heart

- Heron, snake and mongoose (heron, serpent, and mongoose)

- How mice ate iron

- Good makes good, bad makes bad (good makes good, bad makes bad)

- wise enemy (wise foe)

- foolish friend

II. Making friends

Frame narration: pigeon, mouse, crow, turtle and gazelle

- The bird with 2 necks

- The mouse and the two monks

- hulled grain for unhulled

- the too greedy jackal

- Mr. "What-fate-ordains"

- The Weaver, the Stingy and the Bountiful (Poor Somilaka) (Weaver and Stingy and Bountiful)

- the jackal and the bull's cod

- Mice rescue elephants

- the former captivity of the gazelle (deer's former captivity)

III. The war between crows and the owls

Frame narration: the war between crows and owls

- Birds elect a king

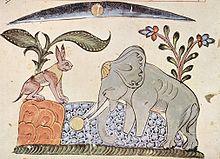

- Elephants and rabbit and moon

- Cat as judge between partridge and hare

- Brahman, goat, and three rogues

- Serpent and ants

- gold-giving serpent

- gold-giving birds

- The self-sacrificing dove

- Old man, young wife, and thief

- Monster, thief, and brahman (ogre, thief, and brahman)

- Prince with serpent in his belly

- The Deceived Wheelwright (cuckold wheelwright)

- The mouse girl wants to marry a mouse (mouse-maiden will wed a mouse)

- the bird whose dung was gold

- Lion and wary jackal (fox and speaking cave) (lion and wary jackal)

- Frogs ride a serpent

- the revenge of the deceived (cuckold's revenge)

- ? The old hamsa as a savior

IV. The loss of friends

Frame narration: monkey and crocodile

- Frog's revenge overleaps itself

- ? The punished onion thief

- Ass without heart and ears

- Potter as warrior

- Jackal raised by a lioness (Jackal nursed by lioness)

- How false wife rewards true love

- Nanda and Vararuci as slaves of love

- Donkey in tiger skin (ass in tiger skin)

- Adulteress tricked by paramour

- Ape and officious bird

- the 4 enemies of the jackal (jackalś four foes)

- the dog in exile

V. The fruits of hastiness

Frame narration: The barber who killed the monks

- Brahmin and faithful mongoose

- the two murderers (the four treasure-seekers)

- Lion-makers

- Tausendklug, Hundertklug, once-wise (thousand-wit, hundred-wit, single-wit)

- Ass as singer

- Two-headed weaver

- Brahmin builds air castles, the Brahmin with the Grüztopf (brahman builds air-castles)

- The apes revenge

- Beast, thief and ape (ogre, thief, and ape)

- blind man, hunchback, and three-breasted princess

- the brahmin haunted by the beast (ogre-ridden brahman)

Editions and translations

- Johannes Hertel (Ed.): Pancantra. A Collection of Ancient Hindu Tales in the Recension, Called Panchakhyanaka, and Dated 1199 AD, of the Jaina Monk, Purnabhadra. Cambridge, Mass. 1908.

- Johannes Hertel (Ed.): The Panchatantra. A Collection of Ancient Hindu Tales in Its Oldest Recension, the Kashmirian, Entitled Tantrakhyayika. Cambridge, Mass. 1908.

- Patrick Olivelle: Pañcatantra. The Book of India's Folk Wisdom. Oxford 1997

literature

- Harry Falk: Sources of Pancatantra. Wiesbaden 1978.

- Ruprecht Geib: On the question of the original version of the pancatantra. Wiesbaden 1969.

- Moriz Winternitz: History of Indian Literature. Vol. 3. Leipzig 1922.

Web links

- Individual translation The too clever fish from the Panchatantra (Project Gutenberg)

- Panchatantra on Google Books

- Panchatantra in German at www.pushpak.de

Remarks

- ↑ Cf. Patrick Olivelle: Pañcatantra. The Book of India's Folk Wisdom. Oxford 1997, p. XII.

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle: Pañcatantra. The Book of India's Folk Wisdom. Oxford 1997, p. XII.

- ↑ Cf. Moriz Winternitz: History of Indian Literature. Vol. 3. Leipzig 1922, p. 273.

- ↑ Cf. Moriz Winternitz: History of Indian Literature. Vol. 3. Leipzig 1922, p. 290

- ↑ Cf. Moriz Winternitz: History of Indian Literature. Vol. 3. Leipzig 1922, p. 294 ff.

- ↑ Christine van Ruymbeke: Kashefi's Anvar-e Sohayli: Rewriting Kalila wa-Dimna in Timurid Herat , Leiden: Brill, 2016, pp. XXIII-XXVIII.

- ↑ cf. Geib p. 95 and foreword Geib

- ↑ The structure and list of the stories are taken from Hertel's Punandra Pancatantra ( Pancatantra - A Collection of ancient hindu tales . Ed. By Johannes Hertel, Harvard University, 1908).