Culture of the Ottoman Empire

| This article was on the basis of substantive defects quality assurance side of the project, Turkey entered. Help bring the quality of this article to an acceptable level and take part in the discussion ! |

Characteristic of the culture of the Ottoman Empire was the integration of the most diverse cultural influences and traditions from the Central and West Asian regions of origin of the Turkic peoples , the different ethnic groups of Anatolia , and the parts of the country that were annexed to the empire through the conquests up to the 17th century. Deeply shaped by Sunni Islam , Ottoman culture is part of Islamic culture . Through trade, pilgrims, diplomacy and war connected over centuries with the Eastern Roman Empire , whose capital Constantinople became the new capital Istanbul in 1453 , the Persian Empire and the Christian states of Western Europe since the Renaissance , the culture of the Ottoman Empire represents a politically and culturally leading country of the Islamic World and at the same time a world power of its time.

|

|

|

|

Left two images: Parade of the glassblowers.

Right two images: Parade of the architects from Surname-i Hümayun , around 1582–1588 |

||

historical overview

The historical development of the Ottoman Empire led to profound changes in cultural creation, which brought with it the new role of the Ottoman sultans, but also the intensive examination of the diversity of the neighboring Islamic and Christian-European cultures.

- 1450 to 1520

With the conquest of Constantinople (1453) and the Mamluk Empire in the Battle of Marj Dabiq near Aleppo and the Battle of Raydaniyya off Cairo in 1517, a large part of the Mediterranean and the core countries of the Islamic world came under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Guided by the imperial idea of Mehmet II , cultural eclecticism shaped the dynamic culture of the 15th century. In the time after the conquest of Constantinople, the beginning of the intensive examination of the Western European world of the Renaissance period and beyond.

- 1520 to 1570

The period after the expansion of the Ottoman Empire is characterized by the expression of the new self-image as a large empire, and by the further political and ideological changes that go hand in hand with the new role as a leading power in the Islamic world.

- 1570 to 1600

The sponsors and artists reacted to the change, differentiation and consolidation of the new rule, but also of the economic and social order, with corresponding changes in their production and in the use of various cultural media.

- 1600 to 1839

With the death of Mehmed III. began a long period of relative stability. During this time, apart from times of armed conflict, trade between the empire and Europe was able to flourish, and traders and pilgrims could travel relatively undisturbed. However, despite the sultan's unchallenged role as defender of the faith and guarantor of social order, tensions arose between the ruling elite in Istanbul and the subjects in the provinces.

- 1839 to 1923

Since the late 18th century, against the background of nationalist uprisings in individual parts of the country and a series of severe military defeats since the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), social and economic stagnation became apparent. In 1839 the proclamation of the Tanzimat began a time of reforms. With the establishment of the Republic of Turkey by Kemal Ataturk , the Ottoman Empire ended in 1923.

The culture of the elite

Within a few generations, the rule of the Ottoman dynasty had spread from Anatolia over the entire Mediterranean region. The Ottoman Empire ruled a large part of the Islamic world, and its sultans also claimed a leading role in the field of religion. This changed the self-perception of the sultans and the ruling elite of the Ottoman Empire. As a result, on the one hand, the visual expression of the now imperial self-image changed, on the other hand, a highly dynamic exchange process developed from the encounter with other cultures, which changed the Ottoman culture comprehensively. In many places and with the participation of rulers, court officials, artists and craftsmen, the patterns and mechanisms of the promotion and organization of art changed. Mainly under the leadership of the court, but influenced by the participation in the large cultural networks of the time, new cultural preferences formed at the court, in the capital and in the provinces.

The Ottoman court manufactories

After the conquest of Constantinople , the city as the new capital of was the Ottoman Empire expanded . In the court workshops ( Ehl-i Hiref ) permanently employed and regularly paid artists and craftsmen of various artistic styles worked. Calligraphy and book illumination were practiced in the scriptorium, the nakkaş-hane . The court manufactories were not locally tied to the Sultan's Palace: besides Istanbul, famous centers of Ottoman handicrafts were mainly Bursa, Iznik, Kütahya and Ușak. As the “silk city”, Bursa was famous for silk fabrics and brocades, İznik and Kütahya for fine ceramics and tiles, and Uşak especially for carpets.

As employees of the court, the artists and artisans were documented in registers, which also provided information on wage payments, special awards from the Sultan, and changes in the artists' salaries. The Court also set prices for individual products in price registers (' narh defter '). In later times the prices set by the court no longer covered the high production costs of the elaborately manufactured products and could no longer compete with the prices that could be achieved in export trade. Complaints from the central administration that the İznik potters would no longer comply with the farm's orders because they were too busy producing mass-produced goods for export are documented.

literature

- 1450-1600

An independent literary tradition can be traced in Anatolia since around the 12th century. One of the earliest known poets in the Turkish language is Yunus Emre , who lived around the turn of the 14th century. By the middle of the 15th century, the western Turkish language in Anatolia had already developed into an independent written language. During the reign of Murad II. (1421–1444, 1446–1451), poems and poems appeared in Turkish, on the basis of which a high literature could develop in the period that followed.

With the political and economic stabilization of the Ottoman Empire, new social elites emerged within the urban culture. In intensive exchange with written Persian and Arabic literature as well as the orally transmitted narrative tradition, a common literary identity was created. During this period, the Ottoman rulers were the main promoters of the literature of their country, if not the Islamic world.

Of world literature importance is in particular the sealing . Based on Persian and Arabic forms, the poem form of the Ghazel received a specifically Ottoman character. Other forms of lyric poetry were the Qasīda (Kaside), the verse romance ( Masnawī ) as well as poetry of the heroic deeds of sultans, princes or princes ( gazavatnameler ). Words, images and themes from the classical Persian works of Saadi , Hafis and Jalal ad-Din ar-Rumi repeatedly served as inspiration for the poets of this time. A well-known poet from early Ottoman times is Bâkî . Poems by one or more authors have been collected in Dīwānen .

Prose works included stories of earlier poets, historical figures, the whims of women and civil servants. The sometimes crude stories about Nasreddin Hodscha, passed down orally throughout the Islamic world, are also known in Western Europe. They were first compiled in Turkish by Aşık Çelebi . Around 1550 the office of the official court historian (" şehnameci ") was created. The şehnameci's office and workshop provided the official historiography of the subsequent rulers of the Ottoman dynasty. At the same time, geographical works such as the “Book of Seafarers” ( Kitab-ı Bahriye ) by the Ottoman admiral Piri Reis were created .

- 1600-1839

At the beginning of the 17th century, the forms of the literary canon were largely determined. The development of Ottoman literature up to the middle of the 19th century is still poorly researched. Nâbi , Nedîm and Nef'i are considered outstanding poets of the 17th and 18th centuries, and the most famous author of a travelogue in prose is Evliya Çelebi . By the end of the 16th century, the Turkish language had absorbed a large number of Arabic and Persian words. This was largely perceived with admiration. Older works were even rewritten in more elaborate Turkish, with Persian or Arabic replacing Turkish words. In the later so-called “ tulip time ”, the principle of linguistic “simplicity and local ties” became popular under the influence of the poet Nâbi. Earlier Turkish works have been reworked, the old-fashioned Turkish replaced by Persian and Arabic words. Persian and Arabic literature was increasingly translated into Turkish. Turkish spoken and written in Istanbul took on the character of a standard of language.

During the 18th and 19th centuries there were three major literary styles: the “Indian” style ( sehk-î hindî ), the most famous representative of which is Fehîm-i Kadîm (1627–1641), the “simple” style Nâbis , and one The spelling is strongly based on the contemporary language, the most prominent representative of which is Nef'i .

- 1839-1923

With the Tanzimat period in the middle of the 19th century, western influences became stronger in politics and literature. The first Turkish novel is Sami Frashëris Ta'aşşuk-ı Tal'at ve Fitnat (“The love of Tal'at and Fitnat”) from 1872. The newspaper Servet-i Fünûn (“Treasure of knowledge “) With the poet Tevfik Fikret and the novelist Halid Ziya Uşaklıgil .

calligraphy

The calligraphy was highly regarded in the Ottoman Empire. According to the strict interpretation of the Islamic ban on images , the visual representation of people or animals is not allowed, so Islamic art has focused particularly on decorative writing and ornament. Ibn Muqla , who lived in the 10th century, and his disciple Ibn al-Bawwab are considered the founders of Islamic calligraphy .

Well-known Ottoman calligraphers were Şeyh Hamdullah , Ahmed Karahisari , and Hâfız Osman . Hâfız Osman, a student of Derviş Ali and Suyolcuzade Mustafa Eyyubi , was under the protection of Köprülü Fazıl Mustafa Pascha . He was the most famous and influential Ottoman calligrapher of the 17th century.

From the time of Mehmed II on, calligraphers were differentiated according to their function. The clerks ( munşi ) mainly used the clerical writings Taliq and Diwani ; the artistic scribes, who owe the most famous works of Ottoman calligraphy, used the circular scripts Naschī , Muhaqqaq and the derived Raiḥān, Sülüs , and Reqa .

In the field of religious literature, specialized writers devoted themselves to the creation of Koran and Hadith manuscripts. The ornamental writing art of the Hilye-i Şerif reached a high point in its design in Ottoman calligraphy. Official documents of the evolving administration of the great empire were made out in sophisticated calligraphy and provided with the seal inscription ( tughra ) of the Ottoman sultans . Particularly valuable registers of religious foundations ("vakıfname") were usually produced in book form and emphasized the piety and social status of the donors. Calligraphic ornaments were used in the early days of Ottoman architecture to decorate building facades. Later, interiors were used, especially in sacred architecture, where the prohibition of images was strictly observed. The qibla wall was often decorated with monumental calligraphic inscriptions. Also known in the western world are the calligraphic Koran inscriptions by Seyyid Kasim Gubari in the Sultan Ahmed Mosque , or the large calligraphic nameplates in the main dome of Hagia Sofia , which were made by Mustafa İzzet in the 19th century.

Miniature painting

Persian miniature painting had a significant influence on the tradition of Ottoman miniature from the very beginning. Before Mehmed II , the Ottoman miniatures often depicted historical heroes using traditional techniques, such as B. Alexander the Great . Under Mehmed II the miniature painters in the writing and painting workshops called nakkaşhane came for the first time with European techniques and subjects, v. a. in contact with the art of portraiture, which from then on they let flow into their works. After the conquest of Tabriz by Selim I in 1514, many Persian masters came to the Ottoman court, whose decorative style developed a great and long-lasting influence on miniature painting. The works of this period found a new subject in court historiography and received further impulses from the rapidly developing nautical and geographical cartography.

The reigns of Suleyman I , Selim II and Murad III. represent the high point of Ottoman miniature art. Among the diverse influences from Western European and Eastern Islamic art, miniature painting shows itself to be a specifically Ottoman art form. Under the aegis of the court historians known as şehnâmeci , some of the most magnificent and art-historically important works are created. The collaboration between Seyyīd Loḳmān Çelebī, the court historian of Selims II, and Nakkaş Osman , the director of the miniature studio , resulted in masterpieces such as Surname-i Hümayun . The miniature painting of the 17th century was determined by dynastic genealogies called silsilenâme . With the miniatures of Abdülcelil Çelebi, called Levni ("the splendidly colored "), the formative position of miniature painting in Ottoman art, which is now increasingly shaped by Western European art forms, ends in the 18th century.

Textile art

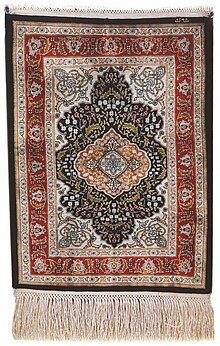

Carpet weaving

The carpet weaving is a traditional craft that far back into the pre-Islamic period. Within the group of oriental carpets , the Anatolian carpet is characterized by characteristic colors, patterns, structures and techniques. The formats range from small pillows ( yastik ) to large carpets that fill the room. The earliest surviving Turkish carpets date from the 13th century. Since then, different types of carpets have been continuously produced in factories , more provincial workshops, in villages, small settlements or by nomads . Each social group knows characteristic techniques and uses characteristic materials. As the images of - mostly Anatolian - carpets in paintings from the Renaissance period show, knotted carpets were exported to Europe in large quantities in the early days of the Ottoman Empire.

Ceramics

Already in Seljuk times, ceramics were widespread throughout Asia Minor and were found in the places Kütahya , Akçaalan and apparently also in Pergamon . The city of İznik became famous for its artistic ceramics during the 15th century . The early ware still clearly shows the influence of Byzantine sgraffito ceramics and Seljuk design. Increasingly, with the expanding long-distance trade, Chinese porcelain came into the empire, whose blue and white style was highly coveted. The production of blue-and-white glazed pottery was strongly promoted in the İznik court factory.

In the 16th century, the color palette of the initially monochrome ceramics expanded. As a building decoration, İznik tiles were initially used to clad building facades, for example the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which was restored under Suleyman I , or on the “Grand Gate” (Bab-i Humayun) of the Topkapı Palace . In later times ceramic tiles were used more as wall cladding for interiors, for example in the Rüstem Pasha and Sultan Ahmed Mosques , particularly in the circumcision room of the Topkapı Palace. Ottoman ceramics were produced for export to Europe as early as the 16th century. In Venice and Padua in the 17th century, besides glass, pottery was also produced which copied the Ottoman style.

In the 17th century, the production of İznik ceramics declined. The city of Kütahya to the east then became the new center of ceramic production in Asia Minor, and since the 19th century the decors and shapes of İznik ceramics have also inspired European porcelain manufacturers.

Language and writing

The Ottoman language was based on Anatolian Turkish. Towards the end of the 15th century, it increasingly included Arabic and Persian elements. It was a variety of Westoghuz and was considered the official and literary language of the Ottoman Empire. As in almost all Turkic languages, the palatal vowel harmony applies , which means that after a dark vowel (a, ı, o, u) only a dark vowel and a light vowel (e, i, ö, ü) can only be followed by a light vowel .

The Ottoman language is divided into three variants:

- Fasih Türkçe - language of administration and poetry

- Orta Türkçe - language of commerce and the upper class

- Kaba Türkçe - language of the lower classes

The Ottomans wrote in Arabic script. The four letters ﭖ pe, ﭺ çim (Tsche), ﮒ gef (Gāf) and ﮊ je (Že) were also adopted by the Persians. Vowels and special characters were also taken from the Arabic alphabet. Numbers were expressed in Arabic numerals.

music

Music in the Ottoman Empire is characterized by the juxtaposition of two musical traditions of different characters. The Turkish folk music ( Türk Halk Müziği ) originated in the culture of Turkish rural communities in Anatolia , the Balkans and the Middle East , and also includes elements of Central Asian Turkkulturen.

The Turkish art music ( Türk Sanat Müziği abbreviated, TSM :; also Klasik Türk Musikisi "classical Turkish music," Saray Musikisi arises from the need of the Ottoman elite to artful music and is from the "Palace Music") Arabic and Persian music influenced even Influences of Indian music and very likely the Greco-Roman music tradition can be identified. During the Ottoman era, Turkish art music was considered the most representative music of Turkey, which was played at the court and in the palaces.

Folk art

Shadow play, folk theater, storyteller

The play of Karagöz, the folk theater “in the middle” and the narratives of Meddah often offer humorous scenic entertainment. In their use of fixed character types and partly by the impromptu developing crudely funny, not always morally correct and criticism not saving action these performances are the European commedia dell'arte approximately comparable. Karagöz and Meddah are part of the intangible heritage of humanity .

Karagöz (shadow play)

Karagöz is a shadow play in which game figures cut out of leather and attached to a stick are moved by a player ( karagözcü , hayyâlbâz ) behind an illuminated curtain. The player speaks the characters' voices, sings, and makes noises. Two musicians accompany the performance with a bell drum ( daire ) and flute ( kaval ). Traditionally, the shadow play was performed during the fasting month of Ramadan and at circumcision festivals. The main characters Karagöz and Hacivat represent opposing characters with fixed characteristics who, in interaction with other characters and mythical creatures, carry the plot in often funny and crude dialogues.

Orta Oyunu (Popular Theater)

Traditional themes of Orta Oyunu ("game in the middle") were typical situations from people's lives and the imitation and caricature of certain types of characters. The partly improvised representations were characterized by witty puns and crude puns .

Meddah (storyteller)

A meddah was a storyteller who usually gave his performance to a small audience, often in a coffee house. The narratives, mostly structured as a dialogue, lived from the presentation and the expressiveness of the narrator. Meddahs often played different characters and used different props to better represent them. Her stories were either classic tales like A Thousand and One Nights, popular tales of the Ottoman Empire, or stories from everyday life. Meddahs were typically traveling artists whose paths led from one major city to another.

Kilim weaving

Today, flat woven fabrics ( kilim ) are understood as the original artistic woven product of the rural villages and nomads , hardly influenced by the art of the Ottoman court manufactory or the requirements of the export market . Kilims were (and are) made by indigenous Kurds , as well as by the Yörüken and other nomadic peoples of Anatolia, who are most closely connected to the traditional way of life of the Turkic peoples , mainly for their own use. As the fabric wore out in use and was never viewed or collected as an expression of art until the 20th century, the oldest surviving specimens from the Ottoman era only date from the 19th century. The patterns of flat weaving follow their own rules, which can be traced back to the early days of the West and Central Asian Turkic peoples. The weaving of purpose-oriented household products became for an indefinite period one of the main media for the cultural and artistic expression of the identity of the rural population and the nomadic tribes.

architecture

Architecture played a leading role in the Ottoman arts until the 18th and early 19th centuries. Because many sultans, princesses, viziers and local rulers had countless mosques, palaces, theological schools, dervish convents, drinking water dispensers and poor kitchens built. The builders spent significant sums on the building. The significant monuments were buildings dedicated to religion. Many Ottomans of the 16th and 17th centuries regarded the architecture of their time as so special that they dedicated a number of poems, sagas and stories to it. This particularly applies to many buildings in Istanbul.

Ottoman cities were made up of two types of buildings. One of the monumental architecture made of stone buildings, which were occasionally provided with decorative additions made of bricks. These buildings were often covered with lead sheets and great importance was attached to the regularity of the stone blocks. This style was juxtaposed with an informal construction method that used the materials available on site. In Istanbul, for example, this was often wood, which was painted in color on the outside. In areas where there was no good access to wood, half-timbered houses were often built, the framework of which was made of wood, but otherwise of clay. Complications often arose with the procurement of lead and iron, which were used not only for domes, but also for window grilles and brackets that held the stone blocks together.

Aspects of everyday culture

kitchen

Large banquets were the focus of festivals and ceremonies at the Ottoman court. Most of the material on food culture in the Ottoman Empire that exists today relates primarily to the food and drinks with which guests were entertained.

An important factor in the distribution of food was the social prestige that the people of that time in the Ottoman Empire associated with certain foods. These criteria not only determine the demand, but also the preparation of the food. Meat was considered one of the most respected foods in the 16th century. The role of meat was so important that even the Sultan's administration secured many officials the right to meat through political measures. Since meat was scarce, it was often prepared in small quantities in sauce or served with vegetables. In Anatolia and Istanbul , sheep and lamb were mainly eaten, but beef was also eaten in other regions, and very little poultry was consumed. Not only was pork not eaten for religious reasons, it was also often considered disgusting. It was consumed nonetheless where larger groups of Christians lived.

Bread was mainly made from wheat in Anatolia , rye was rarely used. However, some farmers also used red millet to bake bread. White bread was most valued in the Ottoman Empire. In houses without an oven , flat flatbread was baked in ashes. The flatbread dough was also used for bags and croissants that were filled with meat and vegetables. Sweet bread was also baked. In addition to bread and meat, wheat and millet porridge were also eaten. In climatically favorable areas, fruit and vegetables supplemented the diet of the people.

The most important drink was water, which was consumed in various qualities. In the 17th and 18th centuries, some donors who wanted to do something good for their fellow citizens had a small kiosk built where water could be obtained free of charge. In addition to water, tea was also drunk, which was often imported from China. In addition, the drink Sahlep was made from the roots of an orchid plant. A hot drink with a soup-like consistency was made from water in combination with some binding agents, including rice. Other drinks were milk, coffee and wine, although this was often forbidden, especially among the Muslims.

Jewellery

Earrings were preferred by those of the Ottoman women who could afford jewelry. These were either made of silver or gold. In the case of better-off women, these were often decorated with pearls or precious stones. Bangles were also often worn. However, unlike earrings, they were made entirely of gold and were sold in pairs. Necklaces and rings were rarely worn by Ottoman women. Found and examined estates of jewelry also suggest that headdresses were rarely worn. But many had belts that were adorned with plenty of silver and gold. The jewels needed for the jewelry were often imported from Bahr. In the Ottoman Empire, jewelry played a far more important role than just adorning the women, because every bride always received a number of different pieces of jewelry at her wedding. This was considered a security for the newly founded family and could be sold in a financial emergency. Most of the jewelers and goldsmiths were Armenians and Jews.

Sports

Ottoman sports included:

Cultural exchange with Europe

- Renaissance period

- Oriental carpets in renaissance painting

- Flowers in the culture of the Ottoman Empire and their way to Europe

See also

- List of Ottoman chroniclers

- Millet system

- Jizya

- Christianity and Judaism in the Ottoman Empire

- Geometric Patterns (Islamic Art)

literature

- Suraiya Faroqhi: Culture and Everyday Life in the Ottoman Empire. From the Middle Ages to the beginning of the 20th century. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39660-7 .

- Suraiya Faroqhi: History of the Ottoman Empire. CH Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-46021-6 .

Web links

- KalemGuzeli.net (Traditional arts in the Ottoman Empire, especially in Turkish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Çiğdem Kafescioğlu: The visual arts . In: Suraiya N. Faroqhi, Kate Fleet (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Turkey . Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2013, ISBN 978-0-521-62094-9 , pp. 457-547 .

- ↑ Eckhard Leuschner, Thomas Wünsch (ed.): The image of the enemy. Construction of antagonisms and cultural transfer in the age of the Turkish wars . 1st edition. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-7861-2684-3 .

- ^ Robert Born, Michael Dziewulski, Guido Messling (eds.): The Sultan's world: The Ottoman Orient in Renaissance art . 1st edition. Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern 2015, ISBN 978-3-7757-3966-5 .

- ↑ Suraiya N. Faroqhi: The Cambridge History of Turkey . Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2006, ISBN 0-521-62095-3 .

- ↑ Mecdut Mansuroglu, The rise and development of written Turkish in Anatolia. Oriens 7 1954, pp. 250-264.

- ↑ Selim S. Kuru: The literature of Rum: The making of a literary tradition. In: Suraiya N. Faroqhi, Kate Fleet (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Turkey . Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2013, ISBN 978-0-521-62094-9 , pp. 573 .

- ↑ Ulrich Marzolph (Ed.): Nasreddin Hodscha: 666 true stories . 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68226-1 .

- ↑ a b Hatice Aynur: Ottoman literature . In: Suraiya N. Faroqhi (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Turkey . tape 3 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2006, ISBN 0-521-62095-3 , pp. 481-520 .

- ↑ a b Hatice Aynur: Ottoman literature . In: Suraiya N. Faroqhi (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Turkey . tape 3 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2006, ISBN 0-521-62095-3 , pp. 481-486 .

- ^ JM Rogers: The chain of calligraphers. In: Empire of the Sultans. Ottoman art from the collection of Nasser D. Khalili . Azimuth Editions / The Noor Foundation, London 1995, ISBN 2-8306-0120-3 , pp. 230-251 .

- ^ JM Rogers: Two master calligraphers of the 16th century. In: Empire of the Sultans. Ottoman art from the collection of Nasser D. Khalili . Azimuth Editions / The Noor Foundation, London 1995, ISBN 2-8306-0120-3 , pp. 50 .

- ^ JM Rogers: Religious endowments. In: Empire of the Sultans. Ottoman art from the collection of Nasser D. Khalili . Azimuth Editions / The Noor Foundation, London 1995, ISBN 2-8306-0120-3 , pp. 82-91 .

- ↑ a b c d Kathryn Ebel: Illustrated manuscripts and miniature paintings. In: Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Masters: Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire . Facts On File, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1 , pp. 266-269f. (online: psi424.cankaya.edu.tr , accessed December 7, 2015)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Suraiya Faroqhi: Culture and everyday life in the Ottoman Empire. From the Middle Ages to the beginning of the 20th century. CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-39660-7 .

- ↑ Werner Brueggemann, Harald Boehmer: Carpets of the farmers and nomads in Anatolia . 1st edition. Verlag Kunst und Antiquitäten, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-921811-20-1 .

- ↑ Korkut Buğday: Ottoman. Introduction to the basics of literary language . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, p. XVII, ISBN 3-447-04154-4 .

- ↑ Celia Kerslake: Ottoman Turkish. In: Lars Johanson, Éva Csató (Ed.): The Turkic languages . Routledge, London 1998, ISBN 0-415-08200-5 , p. 179.

- ↑ Korkut Buğday: Ottoman. Introduction to the basics of literary language . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-447-04154-4 , p. 19.

- ↑ Pertev Naili Boratav : Karagöz. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Volume 4. Brill, Leiden 1978.

- ↑ Pertev Naili Boratav in Encyclopaedia of Islam, article Orta Oyunu - entertainment staged in the middle place

- ↑ Pertev Naili Boratav: Maddah. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Volume 5, Brill, Leiden 1986.

- ↑ Peter Davies: Antique Kilims of Anatolia . WW Norton & Co., New York, London 2000, ISBN 0-393-73047-6 .

- ↑ Fatma Muge Gocek: East West encounters. France and the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth Century. OUP, New York 1987, ISBN 0-19-504826-1 .