Dome of the Rock

| Dome of the Rock Qubbat as-sachra / Kippat ha-Sela |

||

|---|---|---|

Dome of the Rock and Dome of the Chain |

||

| Data | ||

| place | Jerusalem | |

| Construction year | 687-691 | |

| Coordinates | 31 ° 46 ′ 41 ″ N , 35 ° 14 ′ 7 ″ E | |

|

|

||

| particularities | ||

| Between 691 and 1781 the largest wooden dome structure at 20.40 m | ||

The Dome of the Rock ( Arabic قبة الصخرة qubbat as-sachra , DMG qubbatu ʾṣ-ṣaḫra ; Hebrew כיפת הסלע Kippat ha-Sela ) in Jerusalem is the oldest monumental sacred building of Islam and one of the main Islamic shrines . It stands on the Temple Mount in the southeastern part of Jerusalem's old town . According to the current state of research, it was built between 687 and 691 and has been restored, changed and extensively supplemented many times over the centuries, most recently in the early 1990s.

The rock in the center of the building is called אבן השתייה ( Even ha-Shetiyya ) in Hebrew , the founding rock . According to popular Jewish tradition, the world was founded on it, the center of which was the stone in the Jerusalem temple . At this point Abraham wanted to sacrifice his son Isaac ( binding of Isaac ) and this is where the ark of the covenant was located. In the Tanach, however, no relation to earlier or later meanings of the place of sacrifice is given in the story of Isaac's bond ( Gen 22 EU ). The later Temple Mount in turn became the holy place of the Israelites with an altar to end the plague only after King David had bought it from the Jebusite Arawna. ( 2 Sam 24.15 EU )

According to Islamic tradition , Mohammed is said to have started his ascension to heaven and his encounter with the earlier prophets of Judaism and Jesus from this rock . The Islamic tradition and Koran exegesis , according to which not Isaac but Ishmael should be sacrificed, do not connect the rock with Abraham's sacrifice.

The Dome of the Rock is a masterpiece of Islamic architecture of the early Umayyad corporate style and takes over the frühchristlich- Byzantine Zentralbautyp .

The building with a dome originally made of wood (current internal height 11.5 m, diameter 20.40 m) was built over an exposed rock (Arabic sachra ). In archaeological research, the relationship between this rock and previous temple buildings from biblical times is controversial. It is often assumed that the Holy of Holies or the altar of burnt offerings of the ancient Jerusalem sanctuary was on the rock.

The Dome of the Rock was originally - and still is today - not as a mosque , but as a shrine or dome (قبّة qubba 'dome').

The construction

The foundation walls are made of irregular natural stone in a mortar-free construction. Granodiorite , a material similar to granite, has probably been used as the material. The foundations are made of concrete blocks, which are also irregularly dimensioned. The flat roof has hidden internal drainage, it is located about half a meter below the top of the walls. The walls are about 7–8 meters high. There is a tambour above the flat roof , which is about 1/3 of the basic building and 5–6 meters high. A round domed roof made of gold-plated sheet metal is attached to it. From a height of about 3 meters, all walls have a blue ornament with oriental motifs. The entire building is equipped with 7 round arches on each octagon side. These are lined with brick and also provided with blue tile ornaments. The entire facility was originally designed as an octagonal ambulatory .

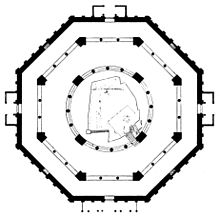

The octagonal floor plan is fitted into a circle with a diameter of almost 55 meters. The innermost circle of columns has a diameter of 20.37 meters and is slightly twisted against the outer octagonal. The cathedral has four entrances, which are arranged in the direction of the four cardinal points . The southern gate is highlighted by a portico and is considered the main entrance.

The dome had a black lead roof until 1962 . During the extensive renovation between 1959 and 1962, it was given aluminum bronze plates hammered with gold leaf . In 1993 King Hussein had these replaced with gold- plated plates. A total of 40 pillars and columns support the dome. The columns are arranged in an octagon and thus also serve as a delimitation of two octagonal walkways.

Near the Dome of the Rock - also on the Temple Mount - is the al-Aqsa Mosque , which was also built under the Umayyads . The erroneously used designation “Umar Mosque” goes back to traditions, the authenticity of which is questionable. According to this, the second caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb is said to have prayed on the Temple Mount (or on the Mihrab of David, today known as the Tower of David at the Jaffa Gate ) on Palm Sunday, April 2, 635 , after the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem . According to other reports, the authenticity of which is also questionable, the Caliph and Sophronius of Jerusalem († around 638) are said to have freed the Temple Mount from rubbish and rubble.

The sources

Research has repeatedly pointed out that Islamic traditions - universal history, local and urban history - contain no contemporary accounts of the construction of the Dome of the Rock. Historians of the Abbasid period deal in their works with the reign of dAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān (ruled 685–705) in detail, but do not mention the building he ordered in Jerusalem.

A more detailed description of the beginnings of building history is first handed down in Faḍāʾil bait al-muqaddas (The Merits of Jerusalem) of the historian and preacher Abū Bakr al-Wāsiṭī, who read his work to some of his students in his house in Jerusalem in 1019. The author relies on authentic reports from local narrators and on information from two people commissioned by the caliph ʿAbd al-Malik to manage the site: from Raǧāʾ ibn Ḥaywa, a well-known traditionalist and legal scholar of his time , and from Yazīd ibn Salām , one of the caliph's wards. According to this report, the construction was initially intended to serve practical purposes “to protect Muslims from heat, cold and snow”.

The report in al-Wāsiṭī also served as a template for later writings on the advantages of Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock. Surprisingly, however, neither in al-Wāsiṭī nor in the later works is the frieze inscription made up of verses from the Koran mentioned. The careful selection of the Koranic verses, which are directed exclusively against the Christian ideas about the image of God (It is not up to God to have any child; 19:35), must have been made by a connoisseur of the Koran, a theologian. Since Raǧāʾ ibn Ḥaywa, born in Baisān - today Bet She'an - (d. 738), was a well-known figure among scholars in Syria and Palestine - Ibn ʿAsākir dedicates 20 pages to his biography in his scholarly biography of Damascus - and on behalf of the caliph had to supervise all construction phases, it is assumed today that he could have been the author of the compilation of the Koran quotes. He was considered a well-known authority in the transmission of contemporary traditions that highlight the role of the caliph ʿAbd al-Malik in the rebuilding of the Temple of Jerusalem ( haikal bait al-maqdis ). He is said to have edged the rock and covered it with cloths. Although the close contacts between the scholar Raǧāʾ ibn Ḥaywa and the caliph and his successors are emphasized by the scholar biographers, they do not report on his activities in the construction of the Dome of the Rock.

Another important source for the origin and description of the Dome of the Rock is the Faḍāʾil bait al-maqdis wa-l-Ḫalīl wa-faḍāʾil aš-Šāʾm (The Advantages of Jerusalem and Hebron and the Advantages of Syria), written by Abū, who is only known through this work l-Maʿālī, Ibn al-Muraǧǧā between 1030 and 1040. He has collected numerous traditions about the merits of Jerusalem and processed them in his work. He describes the building history of the Dome of the Rock in a chapter dedicated to it in almost literal agreement with al-Wāsiṭī, but according to other sources; The contemporary reporters are the key figures mentioned above: the scholar Raǧāʾ ibn Ḥaywa and the warden of the caliph Yazīd ibn Salām. There are no building descriptions or drawings of the building work in Islamic literature. (See below: the Dome of the Rock in local history )

While the authors mentioned above mainly refer to older, written or oral sources, the Persian traveler Nāsir-i Chusrau (died between 1072 and 1078), who visited Jerusalem in 1047, describes the Temple Mount and the Dome of the Rock using his own records. Thus, his report wins as historical documentation from the early 11th century in comparison to that collected by his contemporaries, e.g. T. legendary news of importance.

Important information about the Dome of the Rock and its surroundings during the Ayyubid period can be found in the travelogue of Abū l-Ḥasan al-Harawī, ʿAlī ibn Abī Bakr b. ʿAlī († 1214): al-Išārāt ilā maʿrifat az-ziyārāt. He stayed in Jerusalem from August 1173 to August 1174, during the rule of the Crusaders. After his extensive travels from Constantinople to India and Yemen , he settled in Aleppo, where Saladin had his own madrasa built for him.

Building history

The construction of the Dome of the Rock is in the newer research the caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan and his son and successor al-Waleed ibn 'Abd al-Malik who is also the construction of the (r. 705-715), al-Aqsa Mosque have continued should, attributed. According to the information provided by Sibt ibn al-Jschauzi, construction began in 687; According to the building inscription, he dates the completion to 691–692, d. i. to the year 72 of the Islamic calendar . It is claimed that the construction cost was seven times the annual tax revenue from Egypt.

The building inscription in archaic Kufic style, which is preserved above the cornice on the dome, documents not only the name of the builder, but also the original name of the cathedral, which was only understood as the dome ( Qubba ); of standing here in brackets name is part of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun repaid and replaced by his own name (see below: sacred inscriptions ):

"This dome was built by the servants of God ʿAbd [al-Malik], the commander of the believers, in the year seventy-two, may God accept it for grace."

The French traveler and scientist, later Ambassador to Constantinople , Charles Jean Melchior de Vogüé (1829–1916) first pointed out this change in the founder's name in 1864. M. de Vogüé was able to refer to Arabic sources for the first time: to the geographical-topographical work on Jerusalem and Hebron al-Uns al-ǧalīl bi-aḫbār al-Quds wa-ʾl-Ḫalīl by Muǧīr ad-Dīn al-ʿUlaimī from the 15th century, which the Austrian orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856) had translated into German as early as 1811, also to the Itḥāf al-aḫiṣṣāʾ fī faḍāʾil al-masǧid al-Aqṣā from as-Suyūtī (1445-1505) the merits of Jerusalem and its holy places in the English translation by James Reynolds (London 1836).

Some researchers believe that ʿAbd al-Malik built the building to celebrate the victory of the Arabs over Byzantium and Persia and to demonstrate the triumph of Islam over Judaism and Christianity. According to other views, it was already the founder of the dynasty Muʿāwiya (ruled 661–680) who was the first to tackle the construction of a mosque at this point. Others associate the beginning of the construction work with the name of Emperor Herakleios (ruled 610–641); the building is to be associated with the repatriation of the cross relic stolen by the Persians in 614.

Anastasios Sinaites († after 700), who visited Jerusalem around 660, reports on the tidying up and cleaning work of Egyptian workers on the Temple Mount, which suggests that the Muslims were already interested thirty years before the Dome of the Rock was completed. The Frankish Bishop Arculfus , influenced by Gallo-Roman culture , who had traveled to Palestine around 670 - that is, still during the Caliphate of Muʿāwiya - reports on a square house of prayer on the Temple Mount and describes it as a building erected over debris with thick beams and boards. It is unclear whether this description, which the Irish abbot and hagiographer Adomnan von Iona wrote down as the author of the Liber de locis sanctis , is in fact a forerunner of the Dome of the Rock.

The beginnings of the systematic exploration of the Temple Mount in general and the Dome of the Rock in particular date back to the early 19th century. Domingo Badía y Leblich (born 1767 in Barcelona ; died August 30, 1818 in Damascus ), was the first European who, disguised as a Muslim, visited the holy places of Jerusalem under the name ʿAlī Bey al-ʿAbbāsī. He published his travelogue with maps under the title Voyages en Afrique et en Asie in Paris (1814). The British archaeologist and architect Frederick Catherwood (1799–1854) revised these maps and published them a few years later. These cards are then further drawings of Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock and the other holy places by Charles William Wilson (1836-1905), the 1864-1865 with his friend Charles Warren map for the exploration of Jerusalem still significant (1840-1927) Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem (London 1865) edited, supplemented and corrected.

Charles Warren then published The Survey of Western Palestine (London 1884) with CR Conder , in which he made the remark about access to the Dome of the Rock and the Temple Mount, which is still valid today:

"In the present state of Muslim feeling in the East, there is, however, no hope of excavation being permitted to Christians within the area of the Ḥaram esh-Sherif."

"Given the current sentiments of Muslims in the East, however, there is no hope that Christians will be allowed to excavate in the area of Haram al-Sharif."

The Scottish architect James Fergusson (1808-1886) and the German church historian Johann Nepomuk Sepp (1816-1909) assumed at that time that the Dome of the Rock originally as a church either by Flavius Valerius Constantine or Justinian I had built. J. N. Sepp reassigned the reign of ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwāns dated the building or founding inscription in Kufic style to the time of Saladin .

In 1890 the topographical and historical representation of Palestine, which is still indispensable today, was published, including the Dome of the Rock by Guy Le Strange: Palestine under the Moslems, which devotes 120 pages to the Temple Mount and the Dome of the Rock alone. Le Strange draws on the accounts of Arab geographers as well as Islamic historiography and literature on the merits of Jerusalem; He follows the historical development of the Dome of the Rock up to the year 1500 and refutes Fergusson's assumptions about the origin of the complex (p. 117). According to the state of research at the time, however, he misunderstood the early origins of the traditions relating to Jerusalem and relegated them as literary products to the time after the Crusades.

The dome and the chain dome next to it ( see below ) were originally z. T. open systems. Only the dome has been expanded under al-Ma'mūn by an octagonal wall, whereby the Abbasid Caliph had new mosaic tiles - now with his name - attached to the inside of the arcades without affecting the original construction date. There can therefore be no question of “a fraudulent forgery”, “also not of a damnatio memoriae of a hated predecessor ... rather of a spiritual appropriation of the monument”.

By adding the inscriptions, the caliph undoubtedly gave the building a primarily religious significance. An Umayyad palace south of the Temple Mount and an administrative building ( dār al-imāra ), which are documented in the results of excavations first presented in 1968, are also part of the overall complex .

The construction activity on the Temple Mount initiated a series of foundations of further buildings, fortresses and castles over the entire area of the Marwanids under the successors of ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān. In Jerusalem, the construction of the "Mosque of Jerusalem" was of particular importance, which was later called al-masǧid al-aqṣā based on sura 17, verses 1–2 .

In its original form, the Dome of the Rock looked like the chain dome directly next to it in the SE: an open building with a dome. In 808 and 846 the structure was damaged by a strong earthquake. In 1016 the dome fell on the rock during another earthquake; In 1021 the sixth Fatimid ruler al-Hākim bi-amr Allāh (r. 996-1021) had it rebuilt. Further renovation work is documented inside on the tiles with the date 418 (1027).

During the siege of Jerusalem (1099) the Crusaders took possession of the Dome of the Rock: it became the Templum Domini - the Church of the Crusaders . A marble altar was erected on the rock and a gold cross on the top of the dome. In 1141, three days after Easter, the building was officially consecrated in the presence of Aimerich von Limoges († 1193), the Patriarch of Antioch , and other bishops. Wilhelm of Tire († 1186), the archbishop of Tire and the most important informant about Jerusalem at the time of the Crusades, describes the Dome of the Rock as a foundation by the second caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Ḫattāb. This erroneous designation of the building as the "Mosque of ʿUmar" can still be documented today. According to the archbishop's description, the caliph wanted to restore the temple of the Lord (Jesus), which the Romans had destroyed; however, it does not establish a connection to the Jewish history of the place. The crusaders made the Islamic building their own and saw it as part of their Christian history.

The Syrian scholar Abū l-Ḥasan al-Harawī, who, as mentioned, stayed in Jerusalem from 1173 to 1174, describes in his travelogue the state of the Dome of the Rock at that time. He mentions an inscription above the east portal from the Fatimid period: “This dome ( qubba ) has four gates. The south portal is next to the chain dome, on the vault of which the name of the commander of the believers al-Qāʾim bi-amri ʾllāh and the sura al-Iḫlāṣ with the praise and glorification of God are written. So it is (also) at the other portals. The Franks (ie the Crusaders) have not changed them. "

In 1187, after his victory over the Crusaders at Hattin , Saladin entered Jerusalem and had the golden cross on the dome and the marble cladding of the rock including the altar removed. The rock was ritually cleaned and perfumed. His renovation work is documented inside the dome. They are accompanied by the first twenty-one verses of Sura Tā-Hā and serve as confirmation of the regained Muslim rule over the sanctuary.

The Mameluk ruler Baibars I († 1277) had the dome covered with lead plates and engraved his name in gold on lapis lazuli on the edge of the dome; He had further decorations made on the chain dome.

The Ottoman writer and traveler Evliya Çelebi († after 1683) reports on the capture of Jerusalem under Selim I († 1520) with the following words: “When Jerusalem was (still) in the possession of the Mamelukes, all scholars and pious men went out, to meet Selim Shāh in 922 (1516). They gave him the keys of the Aqṣā Mosque and the Cathedral of God's Rock. Selim prostrated himself and exclaimed: 'Thanks be to Allah! I am now the owner of the first qibla '. ”The ruler's recognition of the religious significance of Jerusalem and the confirmation of Ottoman hegemony over Palestine were subsequently also expressed through extensive construction work on the Dome of the Rock and other Islamic buildings.

The cladding of the facade with the characteristic blue tiles comes from the time of the Ottoman Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent , who had major work carried out on the building between 1545 and 1566. Only the cladding of the base with different colored marble comes from the construction phase. Around 45,000 ceramic tiles were attached to the exterior cladding of the facade, which were replaced with new tiles in the course of necessary repair work. In the years 1960–1961, most of the tiles of Ottoman origin were removed and replaced by reproductions. Some of the originals are deposited in the Islamic Museum of Ḥaram aš-šarīf .

These plinth cladding - see photo on the right - from the time of the Umayyads can also be proven and historically documented in other buildings from that time, such as the remains of the (Khirba) desert palaces in Syria-Palestine. The original design of the windows also shows parallels to the windows of the Umayyad desert castles. Ibn al-Faqīh reported in 903 about stained glass on the Dome of the Rock; Similar fragments of glass were found during the first extensive excavations in inirbat al-Minya. Similar windows with marble grilles and plaster window frames as on the Dome of the Rock are also found in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus .

The extensive renovation under Suleyman I is documented in an inscription dated 1545–1546 directly under the dome, in which the first twenty verses of Surah al-Isra are quoted, the beginning of which: “Praise be to the one with his servant (ie Mohammed) traveled at night from the holy place of worship (in Mecca) to the distant place of worship (in Jerusalem), the vicinity of which we have blessed, traveled ... “ the Islamic tradition connects with the ascension of Muhammad. For the first time, the direct link between the Dome of the Rock and Islamic tradition is made in this inscription.

The sultan had himself immortalized by name on the tympanum of the north portal: "This dome of God above the rock in His holy house was renewed by Sultan Suleyman ..." The inscription was removed during later renovations and deposited in the Haram Museum.

In research it is assumed that the exterior cladding of the building was originally comparable to its interior cladding and consisted of glass mosaics in the representation of trees, fruits and plants. The Dominican monk Felix Fabri , who visited Jerusalem in 1483, before the extensive renovation under Suleyman the Magnificent, reports in his evagatory of motifs such as palm trees, olive trees and angels on the outer cladding of the Dome of the Rock. Since he was not allowed to enter the Temple Mount, his observations were made from a distance. He must have confused the flower motifs with wing-like attachments with angels, which are not detectable anywhere in the building and are not mentioned by the Islamic chroniclers.

Evliya Çelebi reports that Ahmed I (r. 1603–1617) had the rock covered with a canopy richly decorated with jewels and gold ; the corners were fastened with silk ropes.

Extensive renovations took place in the 18th century. Ahmed III. (r. 1703–1730) had building materials shipped from Anatolia and the Black Sea region by sea to Jaffa in 1721 . The building and renovation work carried out by local workers lasted until February 3, 1722. The base area, probably both inside and outside, has been repaired with marble from Europe. The leaded glass windows from the time of Suleyman I below the dome have been replaced by mostly colored glass. The materials, instructions, invoices and inventory lists used are documented in a register ( defter ) that is now kept in the Ottoman archive and the content of which allows conclusions to be drawn about the variety of construction activities.

In the 19th century, especially during the Tanzimat period , the Ottoman rulers had further restoration measures carried out. In 1853, Abdülmecid I. initiated a large-scale project that was only completed under Abdülaziz in 1874–1875. In these works, the Ottoman Empire expressed its efforts to consolidate administrative - and military - control in the provinces through Ottomanization and Islamization.

Up until the middle of the 20th century, the Dome of the Rock looked like it did around 1875. Between 1959 and 1962 and after 1990, major renovations took place to restore the sacred building to its former glory.

“We will never know whether the Ottoman, or the Mameluke, or the Fatimid, or the Umayyad building looked exactly like the current building. Perhaps with the exception of the arrangement of the interior lighting, today's Dome of the Rock is a reasonable approximation of what it was in its last version known to us. "

The political and historical background

Already Ignaz Goldziher wondered in his Muslim Studies (1889-90) why the Umayyadenkalif 'Abd al-Malik in Jerusalem, steeped in history, the "dome" ( al-qubba building) was; citing z. Sometimes relatively late sources - especially according to the historians and geographers al-Ya'qubi and Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamadani (both worked in the late 9th century) - he established a causal connection between the counter caliphate of Abdallah ibn az-Zubair in Mecca and the construction of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. He wrote:

“When the Ummejjad Khalife 'Abdalmalik was concerned that his rival rival in Mecca, ʿAbdallāh b. Zubejr, who could force the Syrians on pilgrimage to the holy places in Ḥigāz, to take the oath of homage to him, who wanted to hold back the pilgrimage to Mecca, so he resorted to the information material of the teaching of the deputy Hagg to Kubbat al-sachra in Jerusalem. "

The German orientalist Werner Caskel pointed out that the first Umayyad caliphs tried to establish a religious and spiritual center in Syria-Palestine. These research hypotheses seem to confirm in some respects the works of local Islamic historians now in print on the merits of Jerusalem; the rock under which rivers of Paradise flow is the closest place to heaven. And in sura 50:41, in which it says

"And listen on the day when someone (the caller) calls nearby (so that everyone can hear it clearly)!"

one identifies the place "up close" ( min makānin qarībin ) with the rock, where on the day of the resurrection the archangel Isrāfīl اسرافيل / Isrāfīl will stand. This eschatological aspect, which is associated with the rock in the Koran exegesis, appears even more clearly in an inscription dated to the year 781 on a hill opposite Sede Boker . The inscription contains the above verse from the Koran in a non-canonized reading: instead of “from near” ( min makānin qarībin ) there is only the word Īliyā , that is, the Arabic name for Jerusalem at that time. It is assumed that content from very old traditions has been taken up in this text variant, which connects the city of Jerusalem with Judgment Day , especially in circles of Syrian-Palestinian Muslims . (See also: the Dome of the Rock in local history )

The climax of the pilgrimage ceremonies in Mecca, the day of Arafat , was also celebrated among the Umayyads at the Dome of the Rock. New research results, which go back to previously unused sources, confirm that during the reign of Caliph ʿAbd al-Malik, the tawāf around the building was exactly the same as around the Kaaba in Mecca. The ʿĪd al-aḍḥā , the festival of sacrifice as the end of the pilgrimage ceremonies, was also celebrated by the region’s Muslims at the Dome of the Rock. The historian Ibn Kathīr (1300–1373) gives a more detailed account of these rites at the Dome of the Rock than his predecessor Yaʿqūbī , according to his source Sibt ibn al-Jschauzi (1186–1256) and sees them in the historical context of the occupation of the Meccan sanctuary by the rival Abd al-Maliks, ʿAbdallah ibn az-Zubair. Nāṣir-i Chusrou also confirms as an eyewitness that Muslims sacrificed animals near the rock on the day of the Islamic festival of sacrifice, as their co-religionists did in Mecca. In 1189 Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn traveled from Safed to Jerusalem to celebrate the festival of the sacrifice there. Ibn Taimiya († 1328) was still familiar with these celebrations, which took place parallel to the pilgrimage to Mecca in Jerusalem.

Taking oaths at this place had the same meaning as at the Kaaba in Mecca or at the pulpit ( minbar ) of the prophet in Medina. Already at the beginning of the 8th century it was the custom, especially among the Muslims of Syria-Palestine, to combine the pilgrimage to Mecca with a visit to the Dome of the Rock and to enter the state of consecration here .

Sacred inscriptions

The construction dates result from inscriptions, papyrus documents and the reports of Arabic historiographers: at-Tabarī , Ibn Kathīr, al-Balādhurī and others. The completion of the Dome of the Rock is clearly documented by the building inscription dated to the Muslim year 72 (691–692). At this point, however, the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mūn, who apparently overlooked the possibility of changing the original construction date when erasing the name of the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik, mentions himself as the client. The changed passage - here in brackets - is written in a style that differs from the original. There it says:

"This dome was built by the servants of God ʿAbd (Allah, the Imām al-Ma'mūn, the commander) of the believers."

The 240 m long inscription tape is composed of a number of quotations from the Koran - also in paraphrased form. The inscription is an integral part of the building that determines its meaning, as Oleg Grabar (1959) first pointed out. On the outside of the inner octagon, the sections begin with the Basmala and creed ( Shahāda ). On the inside of the inner octagon, the Christian doctrine of the divine nature of Jesus is also rejected by verses from the Koran ( sura 4 , verses 171–172, by the paraphrase of sura 19 , verse 33 and by sura 3 , verse 18-20). It also says:

“He (God) has rulership over heaven and earth. He gives life and lets die and has power over everything. "

followed by a statement about Jesus - as a paraphrase of sura 19:33:

"Hail be upon him on the day he was born, the day he dies and the day he is brought back to life."

The interior decorations of the Dome of the Rock show representations of Paradise; Contemporary research explains both this and the inscriptions with the original plan of the builder Abd al-Malik: the building has a religious meaning from the beginning, which is not lacking in anti-Christian polemics . In the inner part of the octagon, opposite the holy rock, there is a passage from Sura 4, verse 171:

"Christ ( al-masih ) Jesus, the son of Mary, is only the messenger of God and his word, which he gave to Mary ..."

"The religious-political goal of the inscriptions is to downgrade Jesus, venerated locally as the Son of God, to his Koranic dimension of a mere servant of God and to give him the prophet of Islam on an equal footing, as a prophet honored in heaven and on earth - as the one in the inscription Verse Q 33:56 quoted several times - to put aside. "

In this sense, Muḥammad is mentioned several times in the inscription as "servant of God" and as "messenger of God". At that time, towards the end of the 7th century, it was also known to the Christians that the Muslims called their prophet a "great messenger (of God)". The archdeacon Georgius, who worked in Egypt around 720, reports that ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Marwān, governor in Egypt and brother of the caliph ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān, had inscriptions placed on the church gates of Egypt, on which Muhammad was the great envoy Called God.

The historian and biographer adh-Dhahabī († 1348) reports in his comprehensive work “History of Islam” (Taʾrīḫ al-islām) that the founder of the Dome of the Rock ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān new coins with the Koran quotation repeated in the inscription “Say : He is God, one and only "( sura 112 , verse 1) and was struck on the edge of the coin with" Muḥammad is the Messenger of God ".

The Koran quotations are the oldest written documents of the Koran in the Kufic style from the year 692, in which diacritical points of Arabic have already been used - even if not consistently .

Two other inscriptions on bronze plaques, which were placed above the east and north portal, also consist of quotations from the Koran, praises of the prophet and the mention of God's punishments and his grace on the day of resurrection. They bear the later added year 831 and the name of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mūn. During restoration work in the 1960s, the badly damaged panels were removed; they are currently in the Ḥaram Museum and are not accessible for research.

Another inscription contains verses 1–21 from the 20th sura ( Tā-Hā ) and is undated. It was probably installed at Saladin's instigation after the reconquest of Jerusalem and was understood as a demonstration of the conversion of the Dome of the Rock, used by the Crusaders as the "Templum Domini" , into an Islamic sanctuary. The inscription, which contains the beginning of the 36th Surah Ya-Sin , appears on the balustrade of the octagon and was added during the extensive renovation work under Suleyman I the Magnificent in the 16th century. The inscription directly below the dome, dated 1545–1546, contains verses 1–20 of the 17th sura ( al-Isrāʾ ); In the construction history of the Dome of the Rock, the Ascension of Muhammad is associated with this place for the first time.

The founding inscription

Inner facade: South - Southeast - East - Northeast - North - Northwest - West - Southwest:

- bi-smi llâhi r-Rahman r-rahimi lā ilaha llāhu wahda-hu lā sarika la-hu la-hu l-mulku wa-la-hu l-hamdu yuḥyī wa-yumītu wa-huwa'Alá kulli šay'in qadīrun ( Sure 64 , 1 and Sura 57 , 2)

In the name of the merciful and gracious God. There is no god but God alone. He has no partner (in rulership). He is in control (over the whole world). Praise him! He gives life and lets die and has the power to do everything.

- Muḥammadun ʿabdu llāhi wa-rasūlu-hu

Muhammad is the servant of God and his messenger

- inna llāha wa-malāʾikata-hu yuṣallūna ʿalā n-nabiyyi yā ayyu-hā llaḏīna āmanū ṣallū ʿalai-hi wa-sallimū taslīman ( sura 33 , 56)

God and his angels speak the blessing on the prophet. You believers! Speak (also you) the blessing on him and greet (him) as it should be!

- ṣallā llāhu ʿalai-hi wa-s-salāmu ʿalai-hi wa-raḥmatu llāhi

May God speak the blessing on him. Salvation be upon him and the mercy of God.

- yā ahla l-kitābi lā taġlū fī dīni-kum wa-lā taqūlū ʿalā llāhi illā l-ḥaqqa ( sura 4 , 171)

People of the Scriptures! Don't go too far in your religion and say nothing against God but the truth!

- inna-mā l-masīḥu ʿĪsā bnu Maryama rasūlu llāhi wa-kalimatu-hu alqā-hā ilā Maryama wa-rūhun min-hu fa-āminū bi-llāhi wa-rusuli-hi wa-lā taqūlū ṯairalāṯatun ʾamintah -ū ḫ ilāhun wāḥidun subḥāna-hu an yakūna la-hu waladun la-hu mā fī s-samawāti wa-mā fī l-arḍi wa-kafā bi-llāhi wakīlan lan yastankifa l-masīhū an yakūna ʾabdan liʾ-lluā l .hi wa- l-muqarrabūn wa-man yastankif ʿan ʿibādati-hi wa-yastakbir fa-sa-yaḥšuru-hum ilai-hi ǧamīʿan (sura 4, 171–172)

Christ Jesus, the Son of Mary, is only the Messenger of God and his word, which he gave to Mary, and Spirit from him. Therefore believe in God and his messengers and do not say (of God that he (is) in one) three! Stop (saying something like that)! This is better for you. God is only one God. Praise be to him! (He is above) having a child. To him belongs (rather everything) that is in heaven and on earth. And God is sufficient as an administrator. Christ will not despise being a (mere) servant of God, not even the angels who are close to (God). And if someone disdains to serve God (w. Him) and is (too) haughty (for it) (that doesn't mean anything). He will gather them (i.e. people) (one day) all to himself.

- Allāhumma ṣalli ʿalā rasūli-ka wa-ʿabdi-ka ʿĪsā bni Maryama wa-s-salāmu ʿalai-hi yauma wulida wa-yauma yamūtu wa-yauma yubʿaṯu ḥayyan ( Sura 19:15 )

Lord, speak the blessing on your messenger and servant Jesus, the son of Mary. Hail on him on the day he was born, the day he dies, and the day he is (again) raised to life!

- ḏālika ʿĪsā bnu Maryama qaulu l-ḥaqqi llaḏī fī-hi yamtarūna mā kāna li-llāhi an yattaḫiḏa min waladin subḥāna-hu iḏā qaḍā amran fa-inna-mā yaqbuūlu la-hu kunb-wa-fa-fa -ʾBudū-hu hāḏa sirāṭun mustaqīmun (sura 19, 34)

This is Jesus, the Son of Mary - to tell the truth about which they (i.e. the unbelievers (among Christians?)) Are (still) in doubt. It is not up to God to have any child. Praise be to him! When he has decided on a thing, he just says to it: be !, then it is. God is my and your Lord. Serve him! It's a straight line.

- šahida llāhu anna-hu lā ilāha illā huwa wa-l-malāʾikatu ulū l-ʿilm qāʾiman bil-qisṭi ( sura 3 , 18)

God testifies that there is no god but him. So do the angels and those who have knowledge. He ensures justice.

- lā ilāha illā huwa l-ʿazīzu l-ḥakīmu (Sura 3, 6)

There is no god but him. He is the mighty and wise.

- inna d-dīn ʿinda llāhi l-islāmu wa-mā ʾḫtalafa llaḏīna ūtū l-kitāba illā min baʿdi mā ǧāʾa-humu l-ʿilmu baġyan baina-hum wa-man yakfuru ure bi-āyāti llāhi-fa-innaī ( Sāyāti llāhi-fa-innaī ( Sāyāti llāhi-s -arna 3, 19)

The (only true) religion for God is Islam. And those who received the Scriptures became divided - in mutual rebellion - only after the knowledge had come to them. But if someone does not believe in God's signs, God is quick to settle accounts.

External facade: South - Southwest - West - Northwest - North - Northeast - East - Southeast:

- bi-smi llâhi r-Rahman r-rahimi lā ilaha llāhu wahda-hu lā sarika la-hu qul huwa llāhu aḥadun llāhu S-ṣamadu lam yalid wa-lam yūlad wa-lam yakun la-hu kufuwan aḥadun ( Sure 112 , 1 -4)

In the name of the merciful and gracious God. There is no god but God alone. He has no partner (in rulership). Say: God is one, eternally pure, has not begotten, and no one has begotten, and there is no one like him.

- Muḥammadun rasūlu llāhi ṣallā llāhu ʿalaihi

Muḥammad is the Messenger of God, may God speak blessings on him.

- bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi lā ilāha illā llāhu waḥda-hu lā šarīka la-hu

In the name of the merciful and gracious God. There is no god but God alone. He has no partner (in rulership).

- Muḥammadun rasūlu llāhi

Muḥammad is the Messenger of God.

- inna llāha wa-malāʾikata-hu yuṣallūna ʿalā n-nabiyyi yā ayyu-hā llaḏīna āmanū ṣallū ʿalai-hi wa-sallimū taslīman (sura 33, 56)

God and his angels speak the blessing on the prophet. You believers! Speak (also you) the blessing on him and greet (him) as it should be!

- bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi lā ilāha illā llāhu waḥda-hu

In the name of the merciful and gracious God. There is no god but God alone.

- al-ḥamdu li-llāhi llaḏī lam yattaḫiḏ waladan wa-lam yakun la-hu šarīkun fī l-mulki wa-lam yakun la-hu waliyun mina ḏ-ḏulli wa-kabbir-hu takbīran ( sura 17 , 111)

Praise be to God, who has not acquired a child (or: no children), and who has no shareholder in rulership, and no friend (who should (protect) him from humiliation! And praise him everywhere!

- Muḥammadun rasūlu llāhi ṣallā llāhu ʿalai-hi wa-malāʾikatu-hu wa-rusulu-hu wa-s-salāmu ʿalaihi wa-raḥmatu llāhi

Muḥammad is the Messenger of God. May God and his angels and his messengers speak blessings on him. And salvation be on him, and the mercy of God.

- bi-smi llâhi r-Rahman r-Rahim lā ilaha llāhu wahda-hu lā sarika la-hu la-hu l-mulku wa-la-hu l-hamdu yuḥyī wa-yumītu wa-huwa'Alá kulli šay'in qadīrun ( Sure 64 , 1 and Sura 57 , 2)

In the name of the merciful and gracious God. There is no god but God alone. He has no partner (in rulership). He is in control (over the whole world). Praise him! He gives life and lets die and has the power to do everything.

- Muḥammadun rasūlu llāhi ṣallā llāhu ʿalai-hi wa-yaqbalu šafāʿata-hu yauma l-qiyāma fī ummati-hi

Muḥammad is the Messenger of God, may God speak the blessing on him and he (will) accept his intercession for his people on the day of resurrection.

- bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi lā ilāha illā llāhu waḥda-hu lā šarīka la-hu Muḥammadun rasūlu llāhi ṣallā llāhu ʿalai-hi

- banā hāḏihi l-qubbata ʿabdu Allāhi ʿAbd [Allāh al-imām al-Maʾmūn amīru] al-muʾminīna fī sanati iṯnatain wa-sabʿīna yaqbalu llāhu min-hu wa-raḍiyabuāu an-hu ā-mīnādu ʿan-hu ā-mīnādu ʿan-hu ā-mīnā

In the name of the merciful and gracious God. There is no god but God alone. Muḥammad is the Messenger of God, may God speak blessings on him. This dome was built by the servants of God ʿAbd [Allaah the Imām al-Maʾmūn, the commander] of the believers in the year two and seventy. May God receive (it) from him and be pleased in him. Amen, Lord of the People of the World. Praise be to God.

It should be noted that the formula “ allāhumma ṣalli ” (Lord, speak the blessing) and the tasliya in its abbreviated form are also used in the secular area, in ancient Arabic inscriptions and graffiti.

The chain dome

The chain dome qubbat al-silsila /قبة السلسلة / qubbatu ʾs-silsila is in the immediate vicinity on the east side of the Dome of the Rock. The construction date is just as little known as the original function of the building. But the Andalusian historian and lawyer ʿAbd al-Malik b. Habib († 852) mentions that the chain dome was built by the caliph ʿAbd al-Malik; thus the small facility must already have existed at the time he was traveling to the Islamic East. Later Muslim authors and geographers such as the Andalusian Ibn ʿAbd Rabbihi and the above-mentioned Persian Nāsir-i Chusrau tie in the description of the function of this small building to the biblical tradition: in the time of the children of Israel the chains would have hung here where right was spoken. According to Islamic tradition, it was David who hung up the chains that only righteous people could hold with their hands. The Arab geographer al-Idrisi , who stayed in Jerusalem during the Crusades in 1154 , describes the place as "the holy of the holy (places)". According to other reports, the treasury ( bait al-māl ), where ʿAbd al-Malik is said to have deposited the funds for the construction of the cathedral , was allegedly located here .

Archaeological investigations have shown that the foundations of the chain dome are at the same level as the dome of the rock and that the column bases are identical to those of the dome of the rock. As Naser Khosrow expressly mentions, the building was never surrounded by a wall; rather, there was a pulpit ( mihrāb ), which was aligned in the axis with the pulpit of the opposite al-Aqsa mosque. The chain dome itself was based on the structural model of the Dome of the Rock in small format and is positioned in the direction of the Qibla in Mecca . It is also believed that the building was originally intended as a model, a kind of template, for the construction of the Dome of the Rock.

Al-maghāra : the cave

The rock is a geological gem made of one of the hardest layers of gray rock found on the Jerusalem plateau. Under the rock is a cave, maghāra /مغارةwhere, according to legend, the "fountain of souls" biʾr al-arwāh /بئر الأرواح / biʾru 'l-arwāḥ is where the souls of the deceased gather twice a week. The floor is covered with marble; a striking, protruding piece of rock is called "the tongue of the rock" lisān as-sachra /لسان الصخرة / lisānu 'ṣ-ṣaḫra , since the rock is said to have greeted the caliph ʿUmar here. Next to the entrance to this cave, under a simple little shrine, one can see the alleged footprint and some whiskers of the Prophet Mohammed.

In this cave under the east wall of the Dome of the Rock there is a miḥrāb , a prayer niche in its archaic form, which Creswell (1979) believes to have originated in the time of the Umayyad ruler ʿAbd al-Malik. The niche made of white marble measures 1.30 / 0.83 m and bears the creed in the old Kufic style in the upper part . Stylistic analyzes and comparisons with other miḥrāb buildings of the subsequent period have shown that the prayer niche in this cave is a later ingredient from the late 10th century.

Al-Mawazin

The stairs leading up to the platform of the entire complex from eight sides end in Byzantine columns in the form of an arcade, the al-mawazin /الموازين / al-mawāzīn / are called 'the scales'; because on the day of the resurrection, according to Islamic tradition, all things, deeds and sins of man are weighed on the scales of God's righteousness. The name is of Koranic origin, because it says in Sura 23 , Verses 102-103:

“Those who then have heavy scales will fare well. But those who have light scales have then lost themselves. "

And in sura 21 , verse 47 it says:

“And for the day (or: the day) of the resurrection we set up the just scales. And then nobody will be wronged (in the least). If it's the weight of a mustard seed, we'll teach it. We calculate (accurately) enough. "

Because of these Koran verses, which then enriched the hadith literature with further statements traced back to the prophet and was able to localize them on the Temple Mount, this place (al-Ḥaram ash-sharīf) is of particular importance in the Islamic world.

According to tradition ( Hadith ) it is the Archangel Gabriel who holds the scales on the day of the resurrection: sahib al-mawazin /صاحب الموازين / ṣāḥibu ʾl-mawāzīn / 'the owner of the scales'. This designation of the entrances to the Dome of the Rock demonstrates its central importance in the religious life of Muslims. In the eschatological beliefs of the Muslims, the entire complex with the rock under the dome is thematized in hadiths.

The upper platform on which the Dome of the Rock is located is only accessible through these steps with the concluding arcades, which were built in the 7th – 8th centuries. Century. The Arab geographer Ibn al-Faqīh al-Hamadānī reports only six staircases in the 10th century; when the other two were added is unknown. The original overall conception of the stairs is definitely part of the Umayyad architecture.

The Dome of the Rock in local history and in Islamic dogma

Local history is an important genre of Islamic historiography . Its content differs from the composition of comprehensive universal history and annalistic historiography. In addition to the often legendary description of the development of settlements and cities, reports about the advantages ( faḍāʾil ) of the region concerned, its buildings and its inhabitants are in the foreground. As a historical-geographical genre with locally-specific traditions, local history is an indispensable source for exploring both Palestine and for describing the holy places, in this case the Dome of the Rock.

It was, as mentioned, Guy Le Strange who first made consistent use of the local historical reports on the merits of Jerusalem ( faḍāʾil bait al-maqdis ); However, he could not assign it exactly to the chronology of Islamic tradition:

The source from which they are derived is to me quite unknown; possibly in the Muthīr we have another specimen of the romantic history books which Islam produced during the age of the Crusades ...

“ The source from which they come is completely unknown to me; With the Muthīr we may have another example of the romantic history books produced by Islam at the time of the Crusades ”

According to recent research results, it is now assumed that traditions about the advantages of Jerusalem were already in circulation in the Umayyad period, in the late 7th and 8th centuries and are probably among the oldest genres of the hadith . The authors of the first collections on the advantages of Jerusalem and its holy places - especially the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aq Aā Mosque - worked in the 10th and 11th centuries:

- Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Wāsiṭī: Faḍāʾil bait al-muqaddas. Little is known about the author's life. A note in the introduction to the work confirms that he was teaching it in his home in Jerusalem in 1019.

- Abū ʾl-Maʿālī al-Mušarraf ibn al-Muraǧǧā ibn Ibrāhīm al-Maqdisī: Faḍāʾil bait al-maqdis wa-ʾl-Ḫalīl wa-faḍāʾil aš-Šām. He was probably a younger contemporary of al-Wāsiṭī, since he was still active in Tire from 1046-1047 . On his travels he gathered traditions about Faḍāʾil in Damascus, Cairo , Aswan and Mecca . As the title shows, al-Muraǧǧā also deals with the virtues of Hebron with the alleged tomb of Ibrāhīm and of Syria-Palestine including Damascus, whose inhabitants are “one of the swords of God” and the land represents “God's riches on earth”.

- Ibn al-Ǧauzī , ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān ibn ʿAlī Abū l-Faraǧ (1116–1201): Faḍāʾil al-Quds . In this book, the author compiles the best-known traditions about the merits of Jerusalem in twenty-five chapters, but mostly confines himself to the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqṣā Mosque. The book ends with a tradition according to which God himself ascended from the rock of the cathedral into heaven. The author rejects the authenticity of this tradition and thus follows his predecessors in adīth-critical literature. It cannot be ruled out that this tradition, which was in circulation in Syria, resonates with theological speculations of Judaism, according to which God raptured from Mount Zion into heaven after Adam's fall, leaving his footprint on the rock.

- Sibṭ ibn al-Ǧauzī (1186–1256) describes in his historical work Mirʾāt az-zamān the origin and construction history of the Dome of the Rock in detail and justifies the building project by the caliph ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān, as mentioned above, with his fight against the so-called Counter-caliph ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair, who seized the sanctuary in Mecca between 682 and 692. ʿAbd al-Malik is said to have asked the Muslims not to make the pilgrimage to Mecca, but to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

The literature on the advantages of the Dome of the Rock also establishes a connection with Koranic revelations and is based on old traditions in the Koran exegesis:

"And listen on the day when someone (w. The caller) calls from nearby (so that everyone can hear it clearly)"

This “nearness” (makān qarīb: near place ) is identified with the rock; al-Wāsiṭī and Ibn al-Muraǧǧā dedicate a separate chapter to these traditions and refer to the exegesis of Qatāda b. Diʿāma, which aṭ-Ṭabarī has already dealt with in his Quran commentary.

The legendary stone slab ( al-balāṭa as-saudāʾ ) next to the rock is the place where prayer is most meritorious; it is one of the particularly revered sites that have arisen over time in the Dome of the Rock and in its immediate vicinity. If one says the prayer on the north side of the rock, one combines both directions of prayer: the old one from the Medinan time of Muhammad to Jerusalem and the Kaaba.

The continuation of the Jewish tradition in Islamic eschatological thinking, which is closely related to the place, can be observed several times in Arabic literature about the advantages of the holy places in Jerusalem. Ibn al-Muraǧǧā mentions an interesting account in his above-mentioned work, which is traced back to Kaʿb al-Aḥbār , a Jew who converted to Islam in the time of Mohammad:

“Kaʿb al-Aḥbār fell into his hands under the books, in which it said:

Īrūšalāyim, that means Jerusalem, the rock, which is called the altar (haikal): I will send to you my servant ʿAbd al-Malik, who will then build you up and decorate you abundantly. Verily, I will bring back his first king to Jerusalem and crown him with gold, silver and pearls. Verily I will send my creation to You and set up my throne on the rock, for I am the Lord God and David is the King of the Sons of Israel. "

Kaʿb al-Aḥbār, who was rooted in the Jewish tradition and converted to Islam, the alleged mediator of this prophecy, died in Ḥimṣ in 652 when ʿAbd al-Malik was six years old and lived in Medina. The Vaticinium ex eventu character of the tradition expresses an essential aspect in the understanding of the foundation in Islamic literature: for the Muslims in the 11th – 12th centuries. In the 16th century, when al-Muraǧǧā and al-Wāsiṭī were active, the temple of Solomon and its altar ( haikal ) were identical to the rock on which God's throne stood.

The motif was also known outside of local history. Already Muḥammad ibn Saʿd († 845) handed down a similar prophecy according to Kaʿb al-Aḥbār, according to which the people ( Ummah ) "of the seal of the prophets" (خاتم النبيين ḫātam an-nabiyyīna , according to sura 33, verse 40), that is, Mohammed will build the temple of Jerusalem ( haikal bait al-maqdis ).

According to Islamic dogma, Islam is the heir of true Judaism, the focus of which was the temple, which was destroyed in AD 70. The Jews lost their sanctuary because they killed their prophets. The Muslims, on the other hand, not only conquered the Temple Mount, but also rebuilt the temple in its old glory. The early Koran exegete Muqātil ibn Sulaimān († 767) clearly expresses this basic dogmatic idea in his commentary on the Koran; after the destruction of the temple by the Romans, the complex remained in ruins until Islam. Then the Muslims rebuilt the temple. Even later Koranic exegesis authorities use this statement by Muqātil; Abū Muḥammad al-Baġawī († 1222) modified the old tradition: “The temple remained destroyed until the caliphate of ʿUmar ibn al-Ḫaṭṭāb. On his orders, the Muslims then rebuilt it. "

Varia

The Dome of the Rock in the history of the reception of architecture

According to current research, which both Islamic historiographers and local historians in Jerusalem confirm, ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān the builder of the dome over the rock, making use of Byzantine architecture and architecture, as well as some builders of Greek origin. The overall architectural concept is similar to the church of San Vitale in Ravenna , built between 525 and 547, and the rotunda in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher , built around 348 under Constantine , in Jerusalem.

According to the current state of research, it is assumed and now confirmed by further archaeological finds that the Dome of the Rock does not represent an Umayyad innovation in its overall concept, but rather belongs to the group of other local Byzantine memorials. After the uncovering and architectural recording of the remains of the so-called Kathisma on the old route between Jerusalem and Bethlehem , a church built around 456 at the time of Saint Theodosius , another architectural forerunner of the Dome of the Rock has been identified. The Kathisma Church is also built in an octagonal shape and in its center is a rock, on which Mary , according to apocryphal Christian tradition, was plagued by birth pangs on the way to Bethlehem, rested and could draw new strength from the fruits and the sap of a palm tree . A palm tree with fruits has been exposed in the mosaic floor. Since the episode is also taken up in the Koran (sura 19, verse 23-26), the church was visited as a place of pilgrimage by both Christians and Muslims in the early 8th century; the expansion of the octagon with a miḥrāb is dated to that time .

In many respects, the Dome of the Rock served as a structural model for the Marienkirche in Aachen, which was completed before 813 . According to Notger von Lüttich († 1008), Charlemagne had the church built according to the example of "the highly wise Solomon (sapientissimi Salamonis)". The building idea goes back to Alkuin (735-804), the most important advisor to Charles, who had expressed the wish "in the Jerusalem of the longed-for fatherland" (i.e. Aachen), "where the templar of the very wise Solomon is artfully erected for God" . Correspondingly, the cleric Wilhelm Tzewers († 1477–1478) , who came from Aachen and worked in Basel, describes the Dome of the Rock as a pilgrim in the Holy Land in his travelogue Initerarius terre sancte and sees it in connection with the Marienkirche.

The extent to which the Dome of the Rock is architecturally related to other monumental structures is, however, controversial in contemporary architectural-historical research.

In Samarra there is the mausoleum of three Abbasid caliphs, the foundation of which goes back to the year 862. This al-Qubba aṣ-ṣulaibīya (aṣ-Ṣulaibiyya dome) as a mausoleum has been identified by the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld . The first description of the building goes back to KAC Creswell (1940). He first associated the shape of the complex with the Dome of the Rock. Like the Dome of the Rock, the building is designed as an octagonal ambulatory with a domed roof. Its construction goes back to the Christian mother of the caliph al-Muntaṣir bi-ʾllāh († 862), who wanted to make her son's tomb “clearly visible” by building, as it is called by aṭ-Ṭabarī . Here are also Al-Mu'tazz († 869) and his successor al-Muhtadi bi-'llāh been († 870) buried. The historian aṭ-Ṭabarī only speaks of a tomb ( maqbara ) in this context , but does not describe the then unusual shape of the mausoleum. This could be explained by the terminology for burial sites that was still missing at the time. Research also suggests that the building may represent the oldest mausoleum of a Shiʿite imam.

The rock floating between heaven and earth

The Andalusian legal scholar and Koran commentator Ibn al-ʿArabī al-Maʿāfirī († 1148 in Fez ) visited Jerusalem in 1093. After returning to his homeland, he wrote his extensive commentary on the Muwaṭṭaʾ by Mālik ibn Anas , in which he puzzled over the meaning of the following verse from the Koran :

"And we let water come down from heaven to a (limited) extent and penetrate into the earth"

In interpreting the word “water” he gives four interpretations; in the fourth variant he writes:

“They say (also): all the waters of heaven are in a cavity under the rock of Bait al-Maqdis. The rock belongs to God's miracles on earth. Because it is a rock that moves in the middle of the al-Aqsa mosque (sic). He has detached himself from all sides and only He holds him tight, who also holds on to heaven, so that he falls to earth only with His permission ... "

After overcoming his fear of entering the cave under the rock, he reports in the same passage in his work:

“I paused for a while, but soon I felt obliged to enter. Then I saw the miracle of all miracles: if you walk along the wall in all directions, you will notice that the cave is detached from the earth on all sides and nothing of the earth is connected to it ... "

The author and draftsman of a book containing 49 folios with 24 drawings about the stations of the pilgrimage routes to Mecca, a certain Sayyid ʿAlī al-Ḥusainī, whose biography is unknown, also contains a drawing about the Dome of the Rock (see illustration), in the center of which the from rocks removed from the earth stand within the building. The title of the drawing is sura 17, verse 1 of the Koran. According to the preface, the author stayed in Mecca in 1559 and wrote his illustrated travel report there.

This legend communicated by Ibn al-ʿArabī was also known to the Damascus scholar ʿAbd al-Ġanī ibn Ismāʿīl an-Nābulusī (* 1641; † 1731), who traveled to Jerusalem in March 1690 with his students and friends. For him, the floating rock is the clear confirmation of Muhammad's ascension, which cannot be covered by the "round structure" (i.e. the dome of the rock). In his travel report Ḥaḍratu ʾl-unsiyya fī r-riḥlati ʾl-Qudsiyya , he reports the above report by Ibn al-ʿArabī through the mediation of al-Ḥalabī († 1634), the author of a biography of the prophets. ʿAbd al-Janī continues his report with the following description, unique in its content:

“It appears, but God knows best, that the Franks ( ie the Crusaders: ifranǧ ) built this building around the rock after the capture of Jerusalem, so that this great apparition, in which the strength of Islam manifests itself, would not survived […] The Franks took Jerusalem for the first time in 1099, seven years after Ibn al-ʿArabī's visit to the city. It is probable that they, the Franks, built this structure around the rock; in doing so they hid this clear sign of the dignity of Islam as the brilliant omnipotence of God when they took control of the land. (They did this) after gaining knowledge of what was publicly known: that our prophet Mohammad (God bless him and give him salvation) when he ascended to heaven on the night of the Ascension, the rock also (with him) (wanted) to go up, but the angels held it back, so that it stood between heaven and earth. This is the greatest miracle of our prophet (God bless him and give him salvation), which confirms the truthfulness of his prophecy and message until the day of resurrection. The Franks deny this, but he (the rock) confirms their lie. They hid it from people's eyes through this structure that they built. God knows best. In any case, their intention was to hide and despise the rock. "

From the above account by an-Nābulusī it emerges that the legend about the rock floating between heaven and earth goes back to an older source. Because he names a certain al-Ḥanbalī and his historical work, who is identical with the Koran exegete and historian Muǧīr ad-Dīn al-ʿUlaymī, ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥanbalī (* 1456; † 1522). an-Nābulusī writes:

“Al-Ḥanbalī reports in the history work (taʾrīḫ): it is common knowledge that the rock is suspended between heaven and earth. It is said that the rock remained in this state until a pregnant woman stepped under it. When she got there in the middle, she was afraid and lost her child. This round building was then built around the rock so that it remained hidden from the eyes of the people. ”Since the history of al-ʿUlaymī has not survived, this report from the early 16th century is only present through the mediation of an -Nābulusī known.

The description of the rock documented by Ibn al-ʿArabī as an interpretation of sura 23, verse 18 has similar motifs in earlier Ḥadīths, which the above-mentioned local historians collected and recorded their works. Abū Bakr al-Wāsiṭī lists traditions about the description of the rock in a dedicated chapter. Thus one lets Muhammad speak in a tradition: "All rivers, the clouds, seas and winds arise below the rock of Jerusalem." According to another tradition, the rivers Syr Darya , Amu Darya , Euphrates and the Nile have their sources below the rock.

The Mosque of the Rock

Another rock is especially venerated during the Islamic pilgrimage . At the foot of the mountain of ʿArafa , two large granite blocks are integrated into a small mosque, which is called ǧāmiʿ aṣ-ṣaḫra , the mosque of the rock. According to Islamic tradition, Mohammed is said to have spoken the formula “here I am, Lord God, at your service” ( labbayka allāhumma labbaika ) on one of these granite blocks on the second day of the pilgrimage . The British naturalist and orientalist Richard Francis Burton , who took part in the pilgrimage in 1853, describes this small enclosure and a drawing he made in his Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah (Chap. Xxix, p. 214) and mentions it the numerous admirers of these granite blocks, near which there is also a prayer niche oriented towards Mecca . At such memorial sites , which are associated with the actions of Muhammad, the object - here the rock - is particularly venerated.

panorama

literature

- Samer Akkach: The poetics of concealment: al-Nabulusi's encounter with the Dome of the Rock. In: Muqarnas 22 (2005), pp. 110-126

- Rina Avner: The Dome of the Rock in Light of the Development of Concentric Martyria in Jerusalem: Architecture and Architectural Iconographie . In: Muqarnas 27 (2010), pp. 31-49

- Jere L. Bacharach: Marwanid Umayyad building activities: speculations on patronage . In: Muqarnas 13 (1996), pp. 27-44

- Eva Baer: The mihrab in the cave of the Dome of the Rock. In: Muqarnas (1985), pp. 8-19

- Max van Berchem : Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum: Jerusalem: Ville. II / 2. Cairo (undated)

- C. Count v. Bothmer: On the architectural-historical interpretation of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG), Supplement Volume III, 2 (1975), pp. 1568–1573.

- Heribert Busse : The Arabic inscriptions in and on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. In: The Holy Land. 109, pp. 8-24 (1997).

- H. Busse: Omar b. al-Hattab in Jerusalem. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam . 5: 73-119 (1984).

- H. Busse: Omar's image as the conqueror of Jerusalem. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam . 8: 149-169 (1986).

- H. Busse: On the history and interpretation of the early Islamic Ḥara buildings in Jerusalem. In: Journal of the German Palestine Association (ZDPV), Vol. 107 (1991), pp. 144–154.

- Werner Caskel : The Dome of the Rock and the pilgrimage to Jerusalem . West German publishing house, Cologne / Opladen 1963.

- Vincent J. Cornell: The Ethiopian's Dilemma: Islam, Religious Boundaries and the Identity of God . In: Jacob Neusner, Baruch A. Levine, Bruce D. Chilton, Vincent J. Cornell (eds.): Do Jews, Christians, and Muslims Worship the Same God? Abingdon Press 2012. pp. 97-98

- KAC Creswell: Early Muslim Architecture. Oxford 1932, part IS 42-94.

- Friedrich E. Dobberahn: Muhammad or Christ? On Luxenberg's reinterpretation of the Kufi inscriptions from 72h (= 691/692 AD) in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. In: Martin Tamcke (ed.): Oriental Christians and Europe - cultural encounter between interference, participation and anticipation. Göttinger Orientforschungen, Syriaca, Volume 41, Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, 2012, pp. 123–157.

- Friedrich E. Dobberahn / Harald Faber, The Early History of Islam - A Gigantic Counterfeit Work ? , in: Hikma - Journal of Islamic and Religious Education, Volume III, Number 4, Kalam-Verlag, Freiburg i Brsg., 2012, pp. 30–58, inbes. P. 48ff.

- Friedrich Erich Dobberahn: The Kufi inscriptions from 72h (= 691/692 AD) on the outside and inside of the octagonal arcade in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem - A contribution to the recent discussion in Islamic studies. In: Friedrich E. Dobberahn / Peter Schierz (Eds.): Room of Encounter - Perspectives of Education, Research and Teaching in the Field of Tension of Multicultural and Multireligious Society , Festschrift for Kurt Willibald Schönherr, 2nd, modified edition, via verbis verlag. Taufkirchen, 2013, pp. 171–225.

- Amikam Elad: Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship; Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage. Brill, Leiden 1995

- Amikam Elad: The history and topography of Jerusalem during the early islamic period: the historical value of Faḍāʾil al-Quds literature . A reconsideration. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI) 14 (1991), pp. 41-70

- Richard Ettinghausen , Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins-Madina: Islamic Art and Architecture 650–1250. Yake University Press 2001, pp. 15-20

- Christian Ewert and Jens-Peter Wisshak: Research on the Almohad mosque . Lief. 1, preliminary stages: hierarchical structures of western Islamic prayer rooms from the 8th to 11th centuries: the main mosques of Qairawan and Córdoba and their spell. Madrid contributions, Vol. 9. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1981, ISBN 3-8053-0471-4 .

- SD Goitein : The Historical Background of the Erection of the Dome of the Rock. In: Journal of the American Oriental Society (JAOS) . 70 (1950), pp. 104-108.

- SD Goitein: Jerusalem in the Arab Period (638-1099). In: The Jerusalem Chatedra . 2, pp. 168-196 (1982).

- Oleg Grabar : The Umayyad Dome of the Rock of Jerusalem. In: Ars Orientalis. 3, pp. 33-62 (1959).

- Oleg Grabar: Art. Ḳubbat al-Ṣakhra. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam , 2. A., Brill, Leiden, Vol. 5 (1986), pp. 298f.

- Oleg Grabar: Notes on the Dome of the Rock . In: Constructing the Study of Islamic Art. Ashgate 2005. Volume 4, pp. 217-229

- Oleg Grabar: The Dome of the Rock. Harvard University Press, 2006

- Georg Graf: How is the word Al-Masīḥ to be translated? In: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG) 104 (1954), p. 119ff.

- Richard Hartmann: The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and its history. Strasbourg 1905. See the advertisement in: Zeitschrift der Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (ZDMG), Volume 67 (1913), pp. 164–167 (G. Beer)

- Sabri Jarrar: Suq al-Maʿrifa: an Ayyubid Hanbalite Shrine in al-Haram al-Sharif . In: Muqarnas 15 (1998), pp. 71-100

- Andreas Kaplony: The Ḥaram of Jerusalem, 324-1099; Temple Friday Mosque, Area of Spiritual Power. Stuttgart 2002 ( Freiburg Islam Studies , Volume 22)

- Jacob Lassner: Muslims on the sanctity of Jerusalem. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 31 (2006), pp. 164-195

- Beatrice St. Laurent & András Riedlmayer: Restorations of Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock and their political significance, 1537-1928 . In: Muqarnas 10 (1993), pp. 76-84

- DS Margoliouth: Cairo, Jerusalem & Damascus. Three chief cities of the Egyptian Sultans. With illustrations in color by WSS Tyrwhitt. London 1907, pp. 175–227 (with illustrations)

- Kathryn Blair Moore: Textual Transmission and Pictorial Transformations: The Post-Crusade Image of the Dome of the Rock in Italy . In: Muqarnas 27 (2010), pp. 51-78

- Ibn al-Murajjā: Faḍāʾil Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalīl wa-Faḍāʾil al-Shām (The Merits of Jerusalem, Hebron and Syria). Ed. Ofer Livne-Kafri, Shfaram 1995

- Gülru Necipoǧlu: The Dome of the Rock as Palimpsest: ʿAbd al-Malik's Grand Narrative and Sultan Süleymans' Glosses . In Muqarnas, 25 (2008), pp. 17-105

- Angelika Neuwirth : The Koran as a text of late antiquity. A European approach. World Religions Publishing House. Insel Verlag Berlin 2010, pp. 249-253.

- Nasser Rabbat: The meaning of the Umayyad Dome of the Rock. In: Muqarnas 6 (1989), pp. 12-21

- ders. The Dome of the Rock revisited: some remarks on als-Wasiti's accounts . In: Muqarnas 10 (1993), pp. 67-75

- Myriam Rosen-Ayalon: The Early Islamic Monuments of al-Ḥaram al-sharīf. An Iconographic Study. In: Qedem. Monographs of the Institute of Archeology. 23. The Hebrew University. Jerusalem 1989

- Raya Shani: The iconography of the Dome of the Rock. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), Volume 23 (1999), pp. 158-207

- Fuat Sezgin: History of Arabic Literature . Volume I. (Leiden 1967)

- Guy Le Strange: Palestine under the Muslims. A description of Syria and the Holy Land from AD 630 to 1300. Cosimo Classics 2010 (reprint of the first edition from 1890). P. 114ff.

- J. Walker: Ḳubbat aṣ-Ṣakhra. In: AJ Weninck and JH Kramers (eds.): Concise dictionary of Islam. Brill, Leiden 1941, pp. 333-336.

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam . New Edition. Brill, suffering. Volume 5, p. 298 (Oleg Grabar)

- Christoph Luxenberg: New interpretation of the Arabic inscription in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. In: Karl-Heinz Ohlig / Gerd-R. Puin (ed.): The dark beginnings. New research on the emergence and early history of Islam , Berlin (Verlag Hans Schiler) 2005, pp. 124–147.

Web links

- Jerusalem. Main view of the Dome of the Rock on lexikus.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Busse, Heribert / Georg Kretschmar (1987): Jerusalem sanctuary traditions in the early church and early Islamic times. Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden; S. 5. ISBN 3-447-02694-4

- ^ Gerald Y. Bildstein in: Encyclopaedia Judaica. 2nd edition (Detroit, 2007): "Even Shetiyya"

- ↑ Christian Ewert (1981): "Just as the Dome of the Rock, by adopting the early Christian-Byzantine central building type, brings the spiritual conquest of the former Christian East to mind, Qairawan could ... etc." - there with further sources

- ↑ Cf. Meik Gerhards (2013): Once again: Heiliger Fels und Tempel

- ↑ Grabar, Oleg (ed.) (2005): Jerusalem, Volume IV - Constructing the Study of Islamic Art. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited, p. 3.

- ↑ H. Busse (1986), pp. 160 and 166-167

- ↑ Olag Grabar: al-Haram al-Sharif: An Essay in Interpretation. In: Constructing the Study of Islamic Art. IV. Jerusalem. Ashgate 2005. S. 2006; before in: Bulletin of the Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies . Volume 2 (2000), pp. 1-13; Gülru Necipoǧlu (2008), p. 19

- ↑ Nasser Rabbat (1993), p. 67; Oleg Grabar: The Umayyad Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. In: Ars Orientalis 3 (1959), pp. 33-35

- ^ Edited by Isaac Hasson. Magnes Press. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. 1979. The Max Schloessinger Memorial Series. Text 3. See Introduction, p. 8

- ↑ al-Wāsiṭī, pp. 81–82; the passage has been translated into English by Nasser Rabbat (1993), p. 68.

- ↑ Volume 18, pp. 96-116

- ^ Nasser Rabbat (1993), p. 70

- ↑ Raya Shani (1999), pp. 188-189

- ↑ Kaplony (2002), pp. 340–342

- ↑ Kaplony (2002), p. 341, note 2

- ↑ Edited by Ofer Livne-Kafri. Shfaram 1995

- ↑ See: Introduction by Ofer Livne-Kafri, p. II

- ↑ Ibn al-Muraǧǧā, pp. 58–59

- ↑ Nasser Rabbat (1993), p. 60 and note 20, where the date of death of Ibn al-Muraǧǧā is erroneously given as 1475.

- ↑ Sefer Nameh. Translated by WM Thackston. New York 1985

- ↑ O. Grabar (2005), p. 218; 220-221

- ^ Carl Brockelmann: History of the Arabic literature . Brill, Leiden 1943. Volume 1, pp. 629-630; Supplement Volume 1, p. 879. Brill, Leiden 1937; Edited by Janine Sourdel-Thomine. Institut Français de Damas, 1957; Ed. ʿAlī ʿUmar. Cairo 1998

- ↑ Sabri Jarrar (1998), p. 86; Kaplony, p. 734

- ↑ Amikam Elad (1995), p. 53.

- ^ Jacob Lassner: Muslims on the sanctity of Jerusalem: preliminary thoughts on the search for a conceptual framework. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. Volume 31 (2006), p. 176 with the reference in footnote 20 to al-Muraǧǧā: Faḍāʾil bait al-maqdis , p. 59 (Arabic text), where this information cannot be confirmed.

- ↑ In his Le Temple de Jérusalem . Paris 1864; see: O. Grabar (2006), pp. 61–61.

- ↑ Oleg Grabar (1959), pp. 33-62; ders. (2006), p. 59 ff.

- ↑ Busse (1991), p. 146 with reference to Olge Grabar: The Meaning of the Dome of the Rock. in which the author revised his theory presented in 1959

- ↑ H. Busse (1991), pp. 145-146.

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland : The earliest Christian writings on Muḥammad: an appraisal. In: Harald Motzki (Ed.): The Biography of Muḥammad . The issue of sources. Brill, Leiden 2000, pp. 276-297; here: p. 289 and note 54

- ↑ H. Busse: The ʿUmar Mosque in the eastern atrium of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. In: Journal of the German Palestine Association. 109: 74-75 (1993); Herbert Donner : Pilgrimage to the Holy Land . Stuttgart 1979, p. 315 ff. With German translation and commentary

- ↑ Busse (2004), p. 431.

- ↑ The Wilson Arch, named after Charles Wilson, with a span of 12.8 m, which served as a bridge to the Temple Mount in the Umayyad period, is now accessible from the Western Wall.

- ↑ Busse (2004), pp. 431-432.

- ^ The Holy Sepulcher and the Temple at Jerusalem. Pp. 67-73. London 1865; William Smith (Ed.): A Dictionary of the Bible. London 1863. Volume 1, p. 1030.

- ^ New architectural studies and historical-topographical research in Palestine. Pp. 44-45. Wuerzburg 1867

- ↑ O. Grabar (2006), p. 216.

- ↑ Reprint Beirut 1965; Cosimo Classics 2000

- ↑ Amikam Elad: The history and topography of Jerusalem during the early islamic period. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), 14 (1991), pp. 41–45; Busse (2004), p. 432.

- ↑ Amikam Elad, (1991), pp. 45-46; Busse (2004), p. 432.

- ↑ Christian Ewert, p. 50.

- ↑ Myriam Rosen-Ayalon (1989), pp. 4-10

- ↑ Jere L. Bacharach (1996)

- ↑ DHK Amiran et alii: Earthquakes in Israel and Adjancent Areas : Macroseismic Observations since 100 BCE In: Israel Exploration Journal 44 (1994), p. 267

- ↑ J. Walker in: AJ Wensinck and JH Kramers (eds.): Handwortbuch des Islams , p. 344 with further sources. on-line

- ^ Adrian Boas: Jerusalem in the time of the Crusades: Society, landscape and art in the Holy City under Frankish rule . London 2001. pp. 109-110

- ↑ Oleg Grabar (2006), p. 161

- ↑ Oleg Grabar (2006), pp. 161–162

- ↑ Kaplony, p. 734; arab. text

- ^ Oleg Grabar: The Umayyad Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem In: Ars Orientalist, Vol. 3, pp. 33ff.

- ↑ Oleg Grabar (2006), pp. 172-175; Miriam Rosen-Ayalon (1989); Register of the mosaics with the inscription, Fig. I. - XIV '

- ^ Yehoshuʿa Frenkel: Baybars and the sacred geography of Bilād al-Shām: a chapter in the islamization of Syria's landscape . In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), Volume 25 (2001), pp. 158–159; Oleg Grabar (2006), p. 184

- ↑ St. H. Stephan ( transl .): Evliya Tshelebi's Travels in Palestine 1648–1650. In: The Quarterly Statement of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine 8, 3 (1939), p. 147

- ↑ Laurent & Riedlmayer (1993), p. 76

- ↑ Grabar (2006), pp. 192-195.

- ↑ A. Schneider & O. Putrich-Reinhard: An early Islamic construction on the Sea of Galilee . Berlin 1937, p. 33

- ^ Myriam Rosen-Ayalon: A contribution to the story of Umayyad windows. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (JSAI), Volume 39 (2012), pp. 367ff; 368-369

- ↑ Oleg Grabar (2006), pp. 196–198

- ↑ Oleg Grabar (2006), pp. 199–200

- ↑ Miriam Rosen-Ayalon (1989), pp. 20–22 and p. 15, Fig. III.6 (after Creswell)

- ↑ St. H. Stephan ( transl .): Evliya Tshelebi's Travels in Palestine. In: The Quarterly Statement of the Department of Antiquites in Palestine. Volume VI. Pp. 92-93; B. St. Laurent and A. Riedlmayer (1993), p. 77

- ↑ B. St. Laurent and A. Riedlmayer (1993), pp. 79-79

- ↑ B. St. Laurent and A. Riedlmayer (1993), p. 77 and p. 84, note 13, cites the document Maliyeden Müdevver Defterler, No. 7829 in the mentioned archive

- ↑ B. St. Laurent and A. Riedlmayer (1993), pp. 80-81. For the following period see: Haim Gerber: Ottoman Rule in Jerusalem (1890–1914) . Berlin 1985

- ^ O. Grabar (2006), pp. 203-204

- ↑ Muhammadan Studies . Vol. II. P. 35.

- ^ Moshe Sharon: Arabic Rock Inscriptions from the Negev. In: Y. Kuris and L. Lender (Eds.) Ancient Rock Inscriptions. Archeological Survey of Israel. Jerusalem 1990. pp. 9-45; here: pp. 10-11; Raya Shani (1999), pp. 176–177 and note 79

- ↑ Amikam Elad: The History and Topography of Jerusalem During the Early Islamic Period: The Historical Value of Faḍāʾil al-Quds Literature: A Reconsideration. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 14 (1991), pp. 56-62; ders. (1995), pp. 53–56 (English translation of the text by Sibṭ ibn al-Jschauzī)

- ↑ Amikam Elad (1995), pp. 61-62

- ↑ Amikam Elad: Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship; Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage. Brill, Leiden 1995, pp. 64-67 with further references

- ↑ See Guy Le Strange (1890), p. 119.

- ↑ H. Busse (1991), p. 150 and the same (1997), p. 8ff.

- ↑ 'God and his angels speak the blessing on the prophet. You believers! Speak (also you) the blessing on him and greet (him) as it should be! '

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland: The earliest christian writings on Muḥammad: an appraisal. In: Harald Motzki (Ed.): The biography of Muḥammad . The issue of the sources. Brill, Leiden 2000, p. 285.

- ↑ adh-Dhahabi: Siyar aʿlām an-nubalāʾ. Volume 4, p. 248. Note 4 of the editor with reference to the work mentioned, Volume 3, p. 279; see also: Oleg Grabar (2006), p. 117.