Islamic eschatology

Eschatology in Islam is the doctrine of 'the last things' at the end of days . Concepts about life after death are found in the earliest suras of the Koran and arefurther elaboratedby both Muslim commentators and Western Islamic studies . Islamic works of ʿIlm al-kalam and Islamic philosophy deal with eschatology under the headingمعاد / maʿād / 'place of return', a word that appears only once in the Koran ( sura 28 , 85) and is often used instead of resurrection .

Koranic sources

In the Qur'an are the oneness of God and the responsibility of people for their deeds on the Last Day ( Arabic يوم القيامة, DMG yawm al-qiyāma 'Day of Resurrection') the two earliest and most important messages that were proclaimed to the Prophet Mohammed in the early Meccan suras . These two messages are so inextricably linked that the Koran equates belief in God with belief in Judgment Day in many places. Recognition of God's oneness, in turn, requires a morally and ethically righteous way of life, and divine judgment is passed on the basis of human conduct in life, followed by final retribution . It is not by chance that those who have earned a place in the Gardens of Paradise are called ahl at-tawheed , i.e. H. referred to as those people who affirm God's oneness. Just as God brings life out of death at any point in time, He can do so, albeit in a more dramatic way, on the Day of Resurrection:

“He brings (in nature) the living out of the dead, and the dead out of the living. And he revives the earth after it has died. In this way you will be brought forth (one day at the resurrection again from the earth). "

Classical Koran comments on the verses with eschatological content emphasize the importance of the fear of eternal punishment as an incentive for lawful behavior. Numerous modern commentaries, however, shift the focus. Instead of the horrors of hellfire, they emphasize the miracle of divine grace , which is supposed to give an orderly structure to life in this world and in the hereafter , as well as human responsibility before God's unchanging presence.

Suras 81 , 82 , 84 and 99 are called apocalyptic suras because they are entirely devoted to describing natural disasters and other spectacular events at the end of days. As an example, the first 14 verses of Sura 81 describe the "envelopment" of the sun, the loss of light from the stars, the trembling of the mountains and the neglect of pregnant camels before the souls are held accountable. Neither the exact time, the exact manner nor the cause of these disasters is mentioned. According to the chronology of the Koran by Nöldeke and Blachère , the most notable apocalyptic parts of the Koran were written at the end of the first and second Meccan periods. These descriptions of the events at the end of the days are often very vivid and colorful, but on the other hand too diverse to give an accurate picture of the events at the end of the world. As Rudi Paret explains in his biography of Mohammed, these images are neither intended to describe an objective reality nor to provide an accurate forecast of the future. Rather, they are primarily intended to shock the audience and announce the horror that will seize the whole world at the end of days. The fact that these early apocalyptic passages do not contain precise descriptions of the resurrection of the dead or the details of the Judgment Day, but only suggest them implicitly, indicates that at least a part of Muhammad's audience in Mecca during the first Quranic revelations with this apocalyptic Imagery must have been familiar. Numerous parallels with Jewish and Christian canonical and apocryphal traditions have been scientifically investigated, although there are also typical Arabic characteristics, such as the neglect of camels in ten months of pregnancy.

life after death

Although the Koran states that everyone will suffer death at some point, it gives only sparse and indirect information on the period between individual death and the end times. After the signs of the “last hour” and the destruction of all creatures, the resurrection and judgment of men will take place on the last day. These signs, the chronological sequence of which remains unclear, include the blowing of the trumpet (among other things in Sura 18 : 99); the coming out of the earth of an animal ( Dabba ), the resurrection in the grave ( Sura 30 : 56); the rising of the dead from the earth ( sura 50:44 ); the setting up of the scales ( sura 55 : 7) and the "accounting" (among other things in sura 13 : 18). Many questions about the afterlife (الآخرة / al-Āchira orمعاد / maʿād ) have been studied in various theological and philosophical traditions; the theological direction of the Ashʿarīya finally confirmed the truth of the traditional narratives about life in the world to come. While Islamic scholars generally agree on a physical resurrection, there are various theories regarding the nature of those bodies, which are outlined below:

- There is a return to the former body. Accordingly, on Judgment Day, the dead awaken from the graves in the restored bodies.

- Man has another invisible body that survives death and carries the soul away after death.

- After death, the soul develops an astral body that is adapted to the spiritual world ( Alem al-Mithal ) and the hereafter.

In an attempt to create a linear narrative that spans the period from the individual death of a person to the Last Day, hadiths and later scholars such as al Ghazali , al-Qurtubi or as-Suyuti have started with the point in time when the angel of death opened the soul of the Carries away the deceased, whereupon the soul is brought back to the deceased person after the burial - or even before - so that they can take part in the funeral ceremonies and the cries. Then she is visited by the angels Munkar and Nakīr and questioned by them, whereby the belief in God must be proven by reciting the creed . Now one or two nameless angels visit the dead and absorb the good and bad deeds that will be revealed on the day of the resurrection. Unbelievers cannot answer the questions and are therefore tortured in various ways, for example, bitten by snakes or punished with “grave chastening” ( ʿadhāb al-qabr ), during which their grave constantly narrows. Believers, on the other hand, are rewarded with the fact that their grave is enlarged or that a window to heaven is opened for them.

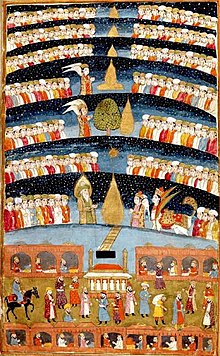

On Judgment Day, people rise from the grave (or Barzach ) and are summoned to the Last Judgment, which according to some sources is to take place in Jerusalem . There they have to wait anxiously and griefly for the moment when it will be seen whether their good or bad deeds outweigh them. The believers, first and foremost the poor, then meet the Prophet Mohammed at a pond (al-Ḥaud), where they are blessed with his intercession . The bridge as-Sirāt , which spans Hell, must be crossed by everyone. Those destined for heaven can cross the bridge safely, the damned fall to hell. At that point, the destined fate - heaven or hell - becomes apparent. According to some traditions, this bridge is said to connect the Temple Mount in Jerusalem with the Mount of Olives and to include seven arches . Some other accounts describe the souls of martyrs staying in the bodies of green birds in the trees of heaven or under God's throne before the resurrection, or it is described that children, martyrs and prophets go to heaven immediately after death.

heaven and hell

Both heaven and hell are given different names in the Koran. Names for heaven are, for example, Janna (جنّة / 'Garden', e.g. B. Sura 2:35 ), Eden ( ʿadn /عدن, e.g. B. Sura 20 : 76) and Paradise ( firdaus /فردوس, Sura 18 : 107 and Sura 23 : 11). Heaven is portrayed in the Koran as a joyful place. The ascension of Muhammad is briefly indicated for the first time in sura 53 , verses 13-18 and is further embellished in later traditions. The water sources and fountains mentioned in the Koran are supplemented in later literature by various entrance gates, castles, pavilions and other buildings, where pearls, precious stones, milk and honey, camels and other animals are in abundance. The inhabitants of heaven receive wine in silver cups from young boys. Above all, however, the heavenly Huris have been described in different ways over the course of time, from at-Tabarī to Omar Chayyam to Christoph Luxenberg .

There are also numerous names in the Koran for hell. Jahannam appears in 109 places, but only takes second place in terms of frequency. Most often - about 125 times - "fire" appears ( nār /نار, e.g. B. Sura 4 : 56). Other names are saʿīr "glowing fire" (4, 10), al-ḥuṭama "the crusher" ( Sura 104 , 4), lazā "blazing fire" ( Sura 70:15 ), saqar "extreme heat" ( Sura 54 : 48 ), al-dschaḥīm ( sura 5 : 10), like “ jahannam ” derived from the Hebrew Gehinnom , and hāwiya “pit” ( sura 101 : 9). In the exegetical literature, these terms correspond to the seven degrees of hell, which go back to the seven gates of hell in Sura 15:44 and are related to the seven degrees of paradise. The punishments and tortures to which the unbelievers are subjected in Hell are both physical and emotional. The Qur'an differentiates between the phrase “painful punishment” ( ʿadhāb īalīm , e.g. Sura 2:10 ), which affects the body, and the less common phrase “degrading punishment” ( ʿadhāb muhīn , e.g. Surah 3 : 178), with psychological implications.

According to popular belief, heaven and hell exist at the same time as this world. The fact that the Prophet Muhammad saw the punishment of Muslim sinners in hell on his night journey is seen by al-Qurtubi as evidence of the existence of hell. While some theologians only hold paradise for ever and believe that hell will pass one day, the majority assume that hell will exist without a time limit. Where the entrance to Hell is is the subject of different views. While al-Qurtubi considered the sea to be the top level of hell, others saw the gateway to the underworld in the sulfur spring in Wadi Barhut in Hadramaut in today's Yemen , or in the Gehinnom valley in Jerusalem. Sura 7:46 mentions a partition between heaven and hell as well as a space in between, which can be compared with the Christian limbo and which al-Ghazālī also calls Barzach . Al-Tirmidhi describes the pitch black darkness of Hell, which is only weakly illuminated by the flames of Hellfire. Mostly extreme heat prevails, but some exegetes also describe the freezing cold of the lowest layer of hell. A tradition recorded by Al-Buchari describes the alternation between scorching heat in summer and icy cold in winter as the two breaths of hell with which God compensates for the tremendous pressure there. Hell is said to contain cities, palaces, houses, wells and prisons, and the landscape is characterized by mountains and valleys, rivers and even oceans - filled with fire, blood and pus. The Koranic expressions “black smoke” in sura 56 : 43 and “steep path” in sura 90 : 11 are interpreted in At-Tabari as denoting mountains of hell. The damned in hell have to feed themselves with thorn bushes ( sura 88 : 6) and dirty water ( sura 69 : 36). At the bottom of Hell grows the "cursed tree" Zaqqum ; its fruits "like demon heads" are intended for the torture of the inhabitants of hell, who have to eat them forever. Various animals such as snakes and scorpions also serve to punish the damned, but there is also talk of the transformation of sinners into animals and their associated dehumanization .

The punishments of hell cataloged in medieval Islamic collections are by no means confined to fire. Different types of execution are listed: heads, hanging, stoning, falling from mountain heights, drowning or trampling by animals. Furthermore, the damned are shamed and humiliated, especially by the fact that they are naked in Hell and that their faces are specially tortured as the seat of honor. The heat of hellfire "lets the lower lip hang down to the navel" ( Ibn Hanbal and al-Tirmidhi ).

To present the traditions about hell in Islam, Muslim scholars in modern times often reissue corresponding hadiths . However, some modern thinkers, beginning with Muhammad Iqbal , disapprove of concrete depictions of otherworldly punishments, and instead a spiritual and personalized interpretation of Hell is proposed. In Western scholarship, the history of hell in Islam has not yet been written.

literature

- Eschatology , Heaven and Sky , Hell and Hellfire in: Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān, Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2001–2001. Digitized

- Afterlife , Hell in: Encyclopaedia of Islam , Third Edition.

- Moritz Wolff : Mohammedan eschatology . Olms, Hildesheim 2004. Reprint of the edition from 1872, Brockhaus, Leipzig digitized

- Helmut Werner: The Islamic Book of the Dead. Concepts of the beyond of Islam. Journal of the German Oriental Society , Volume 159, No. 1, 2009. pp. 185–190.

Individual evidence

- ↑ See: Encyclopaedia of Islam , Volume 5. Brill, Leiden, 1989, p. 235.

- ↑ Jane I. Smith: Eschatology. In: Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān. Volume 2, Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, ISBN 978-90-04-12035-8 .

- ↑ Rudi Paret: Mohammed and the Koran . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1957 (2005 9 ). ISBN 3-17-018839-9 , pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Frederik Leemhuis: Apocalypse . in: Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān, Volume 1. Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2001, ISBN 90-04-11465-3 .

- ↑ Sura 3 : 185

- ↑ Juan Cole Sacred Space And Holy War: The Politics, Culture and History of Shi'ite Islam IBTauris 2002, ISBN 978-1-86064-736-9 , p. 55.

- ↑ Zailan Moris Revelation, Intellectual Intuition and Reason in the Philosophy of Mulla Sadra: An Analysis of the al-hikmah al-'arshiyyah Routledge ISBN 978-1-136-85866-6 page 107

- ↑ This can ultimately be traced back to the book Zechariah (Chapter 14, Zech 14 EU ), which also speaks of an eschatological catastrophe starting in Jerusalem. Lexicon of Dialogue: Basic Concepts from Christianity and Islam

- ^ Spiritual Places in Jerusalem: Mount of Olives

- ↑ Roberto Tottoli: Afterlife . in: Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān, Volume 2. Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002. ISBN 978-90-04-12035-8 .

- ↑ Christian Lange : Hell (jahannam, nār, saʿīr, saqar, Zaqqūm) in: Encyclopaedia of Islam , Third Edition.