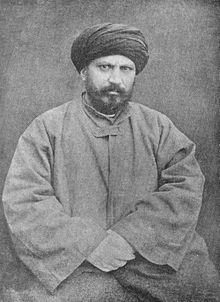

Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani

Sayyid Muhammad ibn Safdar al-Husaini ( Arabic سيد محمد بن صفدر الحسيني, DMG Sayyid Muḥammad b. Ṣafdar al-Ḥusainī ; * 1838 in Asadabad, Iran ; † 1897 in Istanbul ), known as Jamal ad-Din Asadabadi ( Persian جمال الدين اسدآبادى, DMG Ǧamāl ad-Dīn-e Asad-Ābādī ) or Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani ( Arabic جمال الدين الأفغاني, DMG Ǧamāl ad-Dīn al-Afġānī ), was one of the founders of Islamic modernism, a political activist and Islamic theorist in Iran, Afghanistan , Egypt , India and the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century. He is regarded, among other things, as a pioneer of pan-Islamism and anti-colonialism , as a liberal reform theologian and modernist, but also as one of the intellectual founders of political Islam and the Salafism movement of the late 19th and 20th centuries, which demanded a return to true, unadulterated Islam .

Life

Origin and early years

Although many older sources give the city of Asadābād in the Afghan province of Kunar as al-Afghani's origin, analyzes of his biography and the surviving contemporary reports about him (especially writings he left behind in 1891) show that he is from the city of the same name in western Iran , near the city of Hamadān and spent his childhood and youth in Iran. In his early years he was likely to have been in Istanbul as well, although there is no definite evidence of this. He received his religious and political lessons first in his home country, later in Qazvin (from approx. 1848) and Tehran (from approx. 1850) and then (from approx. 1852) in the centers of Shiite teaching in Iraq . He also made the pilgrimage to Mecca and went to Afghanistan in 1866 , where he quickly became an important advisor to the Emir Dost Mohammed . He was hired as a minister by his son Muhammad Azam. When he was overthrown, he did not succeed in gaining a similar position under the new Emir Shir Ali . He was expelled from the country and left Kabul in 1868 . After various intermediate stops (India, Egypt) he went to Istanbul in 1870, where he quickly made contact with reformist (see Tanzimat ) influential circles. A speech on Darülfünun , in which he Rector Hasan Tahsini the philosophy and it represents as a craft prophethood as souls of human society compared, however, aroused such displeasure with the Ulema that he had to leave Istanbul.

He was named "al-Afghānī" in order to escape persecution by the government of Naser al-Din Shah . One of his rivals, al-Sheikh Abū l-Hudā, called him Mutaʾafghin ( Arabic: "who pretends to be an Afghan", although he is said to have been of Iranian descent from Māzandarān ). With this, his contemporaries and opponents tried to prove his Shiʿite inclinations, although he developed his political activities and teaching activities in Sunni-influenced countries of his time and thus emphasized an “Afghan descent” in his writings. In the magazine al-ʿUrwa al-Wuthqā , which he published with Muhammad Abduh in Paris, the last edition of his name mentions himself as Ǧamāl ad-Dīn al-Afġānī. In his handwritten application for admission to the Grand Lodge in Cairo (see below) he introduces himself as Ǧamāl ad-Dīn al-Kābulī. Especially in earlier writings and in those that he wrote in Afghanistan, he called himself "al-Istānbulī" and occasionally "ar-Rūmī" ("the Rhomeans or Anatolians"). According to reports by an Indian government official in Afghanistan, the country was foreign to him and he spoke Persian "like an Iranian".

Cairo years

He then traveled to Cairo in 1871 , where he found some supporters for his ideas, including Muhammad Abduh, the representative of the Islamic reform movement in Egypt . As the number of his followers steadily increased, he was soon seen by the British authorities as a potential problem for the calm in the British colony. He wanted to reject all dogmatism and imitation of well-known works and aimed for political action. During this time he also made friends with the Hungarian orientalist Ignaz Goldziher , who was the first European to study at al-Azhar University during his stay in Cairo .

In 1876 he joined the Masonic Lodge 'Star of the East' ( Kaukab asch-Sharq ) in Egypt, which belonged to the Anglo-Saxon Grand Lodge. In his letter to the lodge, in which he asked for admission, he declared this wish by saying that he was committed to the humanitarian goals of Freemasonry . He became master of the chair in this lodge , but put down the hammer when he realized that his political aspirations were not borne by the brothers. He was succeeded by Abduh. Al-Afghānī established an independent, national lodge in which political engagement, as with the Romanesque lodges, was allowed and which subsequently joined the Greater Orient of France .

When Chediven Taufiq Pasha summoned, he knocked the participation of the people after the shura system before and a choice of elected representatives. In addition to the unification and consolidation of the Muslim nations, his efforts were aimed at developing the state institutions in such a way that Egypt and the other Islamic countries would get rid of the administration of the British. To this end, he envisaged the introduction of a constitution that would have restricted the arbitrariness of those in power. Because of this, he was expelled from the country in 1879.

Al-Afghānī's application for admission to a lodge in Cairo

"Ǧamāl ad-Dīn al-Kābulī, teacher of philosophy in Cairo - God protect it - who was given thirty-seven years of his life, says: I ask the brothers of purity and call the friends of faithfulness, I mean (by that) The Lords of the Sacred Association of Freemasons, without blemish or blame, that they show me the grace and honor to receive me into this righteous association and to incorporate myself into this excellent club.

Yours faithfully,

Thursday, 22nd Rabīʿ II. 1292

(signature) "

Stays in Europe and Afghani's correspondence with Renan

In 1882 Afghani left India and moved to Europe, where in 1883 he discussed his famous correspondence with the French philosopher Ernest Renan on the state of Islam and Islamic civilization. In response to Renan's claim that Islam is contradicting development or modernity, Afghani criticized Renan's discourse. He himself was critical of the current state of Islam, which he saw as falsified by disagreement, superstition and a lack of education, but he rejected any generalization and asserted the perfect compatibility of the true Islam of the forefathers and modernity. Renan was impressed by Afghani's statements and described Afghani as a learned free thinker.

About his stay in Great Britain Afghani wrote in his diary: "I did not see Islam there but Muslims" ( I saw no Islam there, but Muslims ). However, he soon went to Paris for a longer period of time , where his anti-colonial policy activities fell on more fertile ground than in London .

Late years

From London via Tehran he reached Russia by 1889 , where he tried (in vain) to convince the Tsar of a military strike against the British. Further trips to Europe followed, until his return to Iran in 1890/91, where he spoke to Nāser ad-Din Shah , again in vain, for reforms of Islam. After al-Afghānī and his followers threatened to implement their plans themselves, the Shah sent him into exile in Anatolia. He first traveled briefly to London via Iraq . In 1892 he accepted an invitation from Sultan Abdülhamid II and returned to Istanbul. The initially good relationship with the sultan deteriorated noticeably due to increased pressure from his opponents, and his repeated requests for permission to leave the country were rejected.

In 1896 a follower of al-Afghānīs shot Nāser ad-Din Shah. Sultan Abdülhamid refused to extradite Afghans to Iran - it was officially argued that Afghani was an Afghan citizen and therefore not to be extradited - but the Sultan had now finally become suspicious: Al-Afghani spent the rest of his life in honor, but de facto as a prisoner in a "golden cage" in Istanbul.

Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī died of a jaw tumor in Turkey in 1897. After his death at the end of December 1944, his bones were transferred from Turkey to Afghanistan, where they were buried in 1945 on the main campus of Kabul University in a mausoleum in Ali-Abad (a district that has since been renamed Jamal Mina ).

Meaning and ideology

Al-Afghānī is considered to be one of the most important Muslim thinkers and philosophers of the modern age. Two central themes can be found in his ideology: Islamic unity, and the call for a reformed and modernized Islam that adopts western technology and science and thus defends itself against western political and economic dependence. Throughout his life, Afghani agitated against the British, who colonized Egypt and India and oppressed Muslims. Afghani saw the reason for the weakness of Muslims in the lack of unity among Muslims, as well as in the orthodox form of Islam, as it was preached by the legal scholars and philosophers of the 19th century. In the opinion of Orthodoxy, Islam and modernity remained; H. Science and technological progress, incompatible. Afghani protested against this view: Islam and modern technology and knowledge are of course compatible, old ideas have to be broken up, Islam modernized.

Afghani is often seen primarily in his role as the thought leader of modern pan-Islamism , but is also seen as the father of Salafism . Afghani's ideas were carried and developed by his most famous student, Muhammad Abduh, a liberal respected thinker. Together with Raschid Rida , he ushered in the age of nationalist and religious reform in Egypt.

The most important thought figures of al-Afghani and Abduh, who build a bridge between them and today's Islamism , are pan-Islamic. According to al-Afghani, the ideas will take effect when, firstly, all Muslim areas are freed from colonialism and foreign rule , secondly , when Muslims return to the purest sources from the early days of Islam, and thirdly, when Muslims learn technology and social issues Western institutions in targeted selection will have appropriated.

Works

- Supplement to the report on the history of the Afghans. Egypt 1901 (original Arabic: تتمة البيان في تاريخ الأفغان Tatimmat al-bayān fī taʾrīḫ al-Afġān), Miṣr (Cairo), 1318 Islamic lunar year

-

رساله نیچریه (Ressalah e Natscheria). Brochure Naturalism or Materialism in the Persian Language ( Dari ), translated into Arabic by Muhammad Abduh

- German: Gamāladdīn al-Afghānī, subtitle: Refutation of the Naichari sect, in: The political order of Islam. Programs and Criticism between Fundamentalism and Reforms. Original parts from the Islamic world, ed. Andreas Meier, Peter Hammer Verlag , Wuppertal 1994, ISBN 3-87294-616-1 , pp. 78–84

literature

- Muhammad Abdullah: Freemason Traces in Islam. In: Quatuo Coronati. Yearbook. Bayreuth 1983, No. 20, pp. 167-177.

- Werner Ende : Were Ğamāladdīn al-Afġānī and Muḥammad 'Abduh agnostics? In: ZDMG , Supplement 1, 1969, pp. 650-659.

- Marguerite Gavillet: “Unité islamique ou unité nationale? La position de Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Afghānī ”in Simon Jargy (ed.): Islam communautaire (al-Umma). Concept et réalités . Labor et Fides, Geneva, 1984. pp. 81-92.

- Farid Hafez : Islamic Political Thinker. An introduction to the history of Islamic political ideas. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2014 ISBN 3-631-64335-7 , pp. 91-95

- Albert Hourani : Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age 1798-1939 . Oxford University Press , London 1962, pp. 103-129

- Nikki Keddie: An Islamic Response to Imperialism: Political and Religious Writings of Sayyid Jamal al-Din al-Afghani . University of California Press , Berkeley 1968.

- Nikki R. Keddie: Sayyid Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani. University of California Press, Berkeley 1972

- Elie Kedourie : Afghani and 'Abduh . Cass, London 1966

- A. Albert Kudsi-Zadeh: Afghani and Freemasonry in Egypt. In: Journal of the Asian and Oriental Society. (JAOS) 92, 1972, pp. 25-35

- Jacob M. Landau : Prolegomena to a Study of Secret Societies in Modern Egypt. In: Middle Eastern Studies. 1, 1965, pp. 135-186

- Pankaj Mishra : From the ruins of the empire . The revolt against the west and the resurgence of Asia. Translated by Michael Bischoff . Series of publications, 1456. Federal Agency for Civic Education BpB, Bonn 2014 ISBN 3-8389-0456-7 , pp. 61–154: The strange teaching of ... (license from S. Fischer Verlag)

- Imad Mustafa: Political Islam. Between the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas and Hezbollah . Promedia, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-85371-360-0

- Tilman Seidensticker: Islamism. History, thought leaders, organizations. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66070-2 , 2nd edition 2015, ISBN 3-406-66069-X , pp. 39-44 (Chapter: Al-Afghani and Raschid Rida)

See also

Web links

- Muhammad Sameer Murtaza: The Democratization of the Muslim World. Views of the Muslim philosopher Gamal Al-Din Al-Afghani. (PDF file; 111 kB) 2009.

- Bashir A. Ansari: Translation of some sections from his book (…) History of the Afghans

- Birgit Schäbler: Religion, Race and Science. Ernest Renan in dispute with Jamal al-Din al-Afghani

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Britannica Encyclopædia, Online Edition 2007 - Afghanistan

- ↑ In Persian usage his name is associated with his likely Iranian hometown Asad-Ābād in the province of Hamadān (cf. Encyclopædia Iranica ). In addition, the name addition Sayyid indicates his Iranian-Shiite ancestry.

- ^ Jamal al-Din al-Afghani Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Pankaj Mishra: From the ruins of the empire. The Revolt Against the West and the Resurgence of Asia , p. 150.

- ↑ From Reform to Revolution , Louay Safi, Intellectual Discourse 1995, Vol. 3, No. 1 LINK ( Memento from February 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Historia, Le vent de la révolte souffle au Caire , Baudouin Eschapasse, LINK ( Memento from January 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Jameel Ahmad, Studying Islam Website, LINK

- ↑ a b c d NR Keddie: Afḡānī, Jamāl-al-dīn . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica (English, including references)

- ^ NR Keddie, "Sayyid Jamal ad-Din" al-Afghani ": A Political Biography," Berkeley, 1972.

- ^ A. Hourani (1962), p. 108.

- ↑ al-ʿUrwa al-wuṯqā. Dār al-ʿarab. 2nd Edition. Cairo 1958, p. 424.

- ^ Martin Kramer: The Jewish Discovery of Islam. ( Memento from October 24, 2009 on WebCite )

- ↑ a b c Nikki Keddie: An Islamic Response to Imperialism: Political and Religious Writings of Sayyid Jamal al-Din al-Afghani . University of California Press, Berkeley, CA 1968.

- ↑ Nikki Keddie: Sayyid Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani: A Political Biography. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA 1972.

- ^ Albert Hourani: Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age 1798-1939. Oxford University Press, London a. a. 1962, p. 112.

- ↑ Nikki Keddie, 1972.

- ↑ univillage.de

- ↑ 2.bp.blogspot.com

- ↑ iusnews.ir

- ^ Imad Mustafa: Political Islam. Between the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas and Hezbollah . Promedia, Vienna 2013, 23.

- ↑ Elie Kedouri: Afghani and 'Abduh. Cas, London 1996.

- ↑ Pankaj Mishra: From the ruins of the empire. The Revolt Against the West and the Resurgence of Asia , p. 150.

- ↑ Nikki R. Keddie: Sayyid Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani. University of California Press, Berkeley 1972.

- ↑ archive.org

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | al-Afghani, Jamal ad-Din |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | al-Afghani |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | islamic reformer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1838 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Asadabad, Iran |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1897 |

| Place of death | Istanbul |