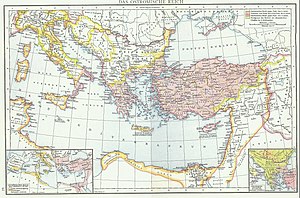

Byzantine Navy

The Byzantine Navy comprised the naval forces of the Byzantine Empire . Like the empire itself, they were a seamless continuation of their Roman predecessors , but played a far greater role in the defense and survival of the empire. While the fleets of the classical Roman Empire hardly ever faced greater threats at sea after the end of the Punic Wars , performed mainly police tasks and always lagged behind the legions of the land army in strength and prestige, the rule of the seas was a vital question for Byzantium, which some historians considered Have called "Sea Rich".

The first threat to Roman hegemony since the naval battle of Actium emerged in the form of the Vandal Empire in the 5th century until it came to an end with the Vandal Empire in the 6th century with the conquest of Justinian I. The reorganization of a standing navy and the introduction of the galley type of dromone around the same time marked the transition from the Roman to the Byzantine navy, which gradually began to develop its own identity. With the beginning of the Islamic conquest in the 7th century, this process continued. With the loss of the Levant and the North African coast as a result of the Arab conquest , the Mediterranean was transformed from a Roman sea into a theater of war between the Byzantine and Arab fleets. In this dispute the navy proved to be an extremely important link between the empire's widely scattered possessions throughout the Mediterranean, but also a decisive factor in the defense against attacks carried out by sea against Constantinople itself. With the new weapon of the Greek fire , the empire was able to do several Repel sieges of his capital and achieve numerous sea victories.

Initially, the defense of the Byzantine coasts and the sea routes to Constantinople was the responsibility of the great Karabisianoi fleet . Gradually, however, it passed to several regional thematic fleets, while in Constantinople itself a central imperial fleet was maintained, which protected the city and formed the core of the fleet for larger expeditions at sea. By the 8th century, the well-organized and well-maintained Byzantine navy regained the upper hand in the Mediterranean. The naval war with the Muslim fleets continued with varying degrees of success, but by the 10th century the Byzantines succeeded in reestablishing maritime supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean.

During the 11th century, the navy, like the empire itself, began to decline. With the new threats from the Latin West, the Byzantines were increasingly forced to rely on the fleets of Italian city-states such as Venice or Genoa , with dire effects on the sovereignty and economy of the empire. A period of consolidation under the Komnenen dynasty was short-lived, followed by a renewed decline, until the decline culminated in the destruction of the empire in the catastrophe of the Fourth Crusade . After the restoration of the kingdom in 1261 several emperors attempted Palaiologoi dynasty a revival of the Navy, but their efforts were only briefly successful. By the mid-14th century, the Byzantine navy, once capable of providing hundreds of warships, sank to a few dozen at best, and control of the Aegean was finally in the hands of the Italian and Ottoman fleets. Even so, the Byzantine naval forces remained in active service until the end of the empire in 1453.

Activities and commitment

Early Byzantine period

Civil Wars and Barbarian Incursions: the 4th and 5th Centuries

The Byzantine Navy, like the Eastern Roman Empire itself, represented a seamless continuation of the Roman Empire and its institutions. After the battle of Actium in 31 BC. The Mediterranean Sea had become a Roman sea and was surrounded on all sides by Roman possessions, so that there was no longer any need for a large, constantly maintained fleet. In the absence of external threats, the Roman navy dealt mainly with maritime police tasks and provided escort to troop transports and cargo ships. There were no more major naval battles, such as the Punic Wars , and the Roman fleets largely consisted of smaller vehicles that were appropriate for the new tasks.

By the early 4th century, the constantly maintained Roman fleets had dwindled so that the naval forces of the rival emperors Constantine and Licinius , who met in 324, consisted to a large extent of newly built ships or ships confiscated from the ports of the eastern Mediterranean . In late antiquity , for example during the civil wars of the 4th and 5th centuries, war at sea played a larger role again, although the fleets mostly served as escorts for troop transports. In the first quarter of the 5th century the Western Roman Empire again maintained larger naval forces in the western Mediterranean, which were mainly deployed from North Africa, but the Western Roman naval rule arose a more dangerous enemy than North Africa as a result of the migration of peoples in the 30s of the 5th century Vandals was conquered.

The new Vandal Empire under its King Geiseric , which ironically had its capital in Carthage , immediately began to raid the coasts of Italy and Greece, even Rome itself fell victim to one of these raids in 455 and was looted . For the next two decades, the Vandals continued to attack, despite all Roman attempts to repel them. The Western Roman Empire was powerless against it, its navy practically melted to nothing, but the emperors of the east could still fall back on the resources and seafaring experience of the eastern Mediterranean. A first Eastern Roman expedition in 448 only reached Sicily, however, and in 460 the Vandals attacked and destroyed a Western Roman invasion fleet lying near Carthago Nova . Finally, however, in the year 468, a huge Eastern Roman expeditionary force was equipped under the command of Basiliscus , which allegedly comprised 1,113 ships and 100,000 soldiers, but the expedition failed on a terrible scale. About 600 ships were lost to fire , and the immense cost of 130,000 pounds of gold and 700 pounds of silver put the Eastern Roman Empire on the verge of bankruptcy. The Romans were therefore compelled to come to terms with Geiseric and sign a peace treaty. After Geiserich's death in 477, however, the attacks on the Roman coasts stopped.

The 6th century - Justinian restores Roman rule in the Mediterranean

In the 6th century there was a renewal of Roman naval power. When the conflict with the Ostrogothic empire Theodoric the Great flared up in 508, Emperor Anastasios I sent a fleet of a hundred ships to devastate the coasts of Italy. In 513 the Thracian army master Vitalian rebelled against Anastasios, and the rebels assembled a fleet of two hundred ships. However, despite some initial successes, this was destroyed by the loyal Admiral Marinus, allegedly with the help of a highly flammable warfare agent, which could have been an early forerunner of the Greek fire.

In 533 the Roman general Belisarius took advantage of the absence of the Vandal fleet that operated near Sardinia to cross an army of 15,000 men to North Africa with a force of 92 dromons and 500 transport ships. This began the first of Justinian's wars of reconquest , the war of vandals . These wars consisted essentially of amphibious operations, which depended heavily on the control of the sea routes in order to be able to supply and connect the widely spread garrisons and combat groups. This did not escape the enemies of Constantinople, and as early as the 520s the Ostrogoth king Theodoric is said to have considered building a strong fleet that was to be directed against the Vandals and Byzantium alike. Due to his death in 526, however, these plans were no longer fully implemented. In the year 535 the Gothic War began , two Roman fleets operated on the coasts of Italy and deposited Belisarius first on Sicily , then on the Italian mainland, while the other attacked Dalmatia . The Roman rule of the sea allowed the relatively small army of Belisarius to occupy almost all of Italy by 540.

As early as 541, however , the new Ostrogoth king Totila created a fleet of 400 ships to challenge the empire for sea supremacy in Italian waters. Two Roman fleets were destroyed near Naples in 542, and Belisarius personally commanded two hundred ships against the Goths' fleet in 546, which was blocking the mouth of the Tiber - a failed attempt to relieve Rome. In 550 Totila landed in Sicily, in the following year his three hundred ships of three hundred ships recaptured Sardinia and Corsica and sacked the coasts of Corfu and Epirus . However, a defeat in the naval battle of Sena Gallica marked a change in the fortunes of war, and with the final conquest of Italy and southern Spain, the Mediterranean had once again become a "Roman sea".

Despite the loss of large parts of Italy to the Lombards in the following period, Byzantium defended its maritime domination, also because the Lombards themselves were not seafarers, and was therefore able to defend various coastal strips in Italy for centuries. The only major operation of the navy within the next eighty years took place with the siege of Constantinople by the Sassanid Persians , the Avars and the Slavs in 626. When a fleet of Slavic rowing boats tried to cross Persian troops to Constantinople, they got caught in a Byzantine ambush and were destroyed, so that the Persians could not cross the Bosphorus and ultimately the Avars had to withdraw.

The fight against the Arabs

The Emergence of the Arab Sea Threat

During the 640s, with the Arab conquest of Syria and Egypt, a new threat arose for the Eastern Roman Empire. With the loss of the two provinces not only had important sources of taxpayers' money and soldiers been lost, but the Arabs were also able to create their own navy. After the brief reconquest of Alexandria in 644 had shown them the usefulness of a strong fleet, the new masters also began to set up naval forces. Since the new elite mostly came from the interior of the Arabian Peninsula , they relied heavily on the resources and knowledge of the locals, not least the Egyptian Copts, who had provided ships and crews to the empire only a few years earlier. However, there are also indications that shipbuilders from Persia and Mesopotamia were also employed in the new naval bases in Palestine . Since there are no illustrations from the period before the early 14th century, no statements can be made about the nature of the early Muslim warships, although it is generally assumed that they were not too far from the existing tradition of the Mediterranean region. Due to a largely uniform nautical nomenclature and the centuries-long exchange between the two cultures, Byzantine and Arab ships were very similar in many ways. These similarities also extended to tactics and the general organization of the fleet; translations of Byzantine military manuals, for example, were also available to Arab admirals.

- Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor , Annus Mundi 6165.

|

After the occupation of Cyprus and raids on Rhodes , Crete and Sicily, the young Arab Navy inflicted a decisive defeat in the Battle of Phoinix in 655 for the Byzantines, personally commanded by Emperor Constans II . This devastating blow opened the Mediterranean for the Arabs and was the prelude to a centuries-long chain of conflicts over control of shipping routes in the Mediterranean. From the reign of Muʿāwiya I on, raids on the coasts intensified while preparations were made for the decisive attack on Constantinople itself. During the long siege of Constantinople by the Arabs, it was up to the Byzantine navy to save the empire's existence. With a newly developed secret weapon, the "Greek fire", the Arab fleets could be destroyed and the besiegers forced to surrender, the Arab advance in Asia Minor and in the Aegean Sea also came to a standstill. Soon after, a thirty year truce was signed.

In the 680s, Justinian II paid great attention to the needs of the navy, strengthening them by relocating more than 18,500 Mardaites along the southern shores of the empire to serve as marines and rowers. Nevertheless, the Arab threat at sea increased again as they progressed along the North African coast. The last Byzantine base, Carthage , fell in 698, although a Byzantine fleet briefly managed to retake it. The Arab governor Musa ibn Nusair built a new city with a naval port near Tunis , and a thousand Coptic shipbuilders were brought there to build a new fleet that was to wrest From Byzantium control of the sea in the western Mediterranean. At the beginning of the 8th century, incessant series of raids began on Byzantine possessions in the western Mediterranean, especially on Sicily. In addition, the fleet enabled the Arabs to complete the conquest of North Africa and to cross over to Spain, where they defeated the Visigoth army and destroyed the Visigoth Empire in 711 .

Byzantine counter-offensives

The Byzantines could do little to counter the Muslim advance in North Africa, since the two decades between 695 and 715 were marked by serious internal conflicts. However, they carried out raids on enemy coasts in the eastern Mediterranean, such as B. a particularly successful one in 709 against Egypt, where they were able to capture the local admiral. They were well aware of the looming danger of another major attack, and when Caliph Al-Walid I gathered his forces for a new campaign against Constantinople, Emperor Anastasios II prepared the city for defense and carried out an unsuccessful preventive attack against enemy preparations at sea . Anastasios was soon by Theodosius III. overthrown, who in turn was soon replaced by Leo III. , the Isaurians, who had to face the threat of the third and final siege of Constantinople by the Arabs . Once again, the Greek fire proved to be the decisive weapon with which the city's supply routes to the sea could be kept open and the besiegers cut off. A hard winter and attacks by the Bulgarians also drained the strength of the attackers, who finally had to withdraw.

On the retreat from the Bosporus, the remnants of the Arab fleet were further decimated in a storm, and the Byzantine forces took advantage of the enemy's weakness to launch their own offensive. An Eastern Roman fleet sacked Laodicea , while an imperial army drove the Arabs out of Asia Minor. For the next three decades, naval warfare on both sides was largely limited to looting the opposing coasts, while the Byzantines also repeatedly attacked the Muslim naval bases in Syria ( Latakia ) and Egypt ( Damiette , Tanis ). In 727, a survey of the themed fleets, which probably broke out due to the iconoclastic policy of the emperor, was suppressed by the imperial central fleet through the use of Greek fire. Despite the resulting losses, Byzantium dispatched no fewer than 390 ships to attack Damiette as early as 739, and in 747 the Byzantine Navy, with the help of ships from the Italian city-states, prepared the combined fleets of Syria and Alexandria for a decisive defeat at Cyprus, which formed the Umayyad caliphate deprived of its fleet.

Soon thereafter, the Byzantines also destroyed the Muslim fleets in North Africa and regained complete naval control in the Mediterranean. This made it possible for the empire to cut off Muslim maritime trade, and with the collapse of the Umayyad Empire and the increasing fragmentation of the Islamic world, the Byzantine Navy was soon the only well-organized naval force in the Mediterranean, Byzantium in the second half of the 8th century secured complete naval supremacy. During this time, guarding the coasts of Syria against attacks by Byzantine fleets was supposedly considered a more devout act than spending night in prayer in the Kaaba .

These successes made it possible for Emperor Constantine V to use the fleet during his campaigns against the Bulgarians in the Black Sea. A fleet of 800 ships sent in 763, transporting 7,600 horsemen and some infantry, landed in Anchalius and achieved a great victory, but already in 766 another fleet, allegedly consisting of 2,600 ships, was lost en route to the same destination.

Return of the Muslim threat

- Ibn Chaldun , Muqaddimah , III. 32.

|

The supremacy of the Byzantine navy lasted until the early 9th century when a chain of disasters ushered in a new era of Muslim expansion. Byzantium suffered a heavy defeat in the Gulf of Antalya as early as 790, and new raids began on Cyprus and Crete during the reign of Hārūn ar-Raschīd . New powers arose around the Mediterranean, first and foremost the Carolingian Franconian Empire . In 803, the Treaty of Pax Nicephori recognized the de facto independence of the Republic of Venice , which was reinforced by a Byzantine defeat in an attack on the city in 809. At the same time, the Aghlabid dynasty consolidated in Ifrīqiya, Africa , which immediately led to new raids on the coasts of the central Mediterranean Sea.

The Byzantines, on the other hand , suffered a series of devastating defeats, and in 820 Thomas the Slav led a revolt against the empire, which was joined by a not inconsiderable part of the imperial forces, and a. also the themed fleets. Although the uprising was suppressed, it had dangerously weakened the defense of the empire, and between 824 and 827 Crete fell into the hands of a group of Andalusian exiles (see Emirate of Crete ). Three attempts to recapture failed over the next few years, and the island became the central base of Muslim pirate activity in the Aegean, which had a decisive influence on the balance of power in the region. In the Levant, under the Abbassid caliphate, a new Arab navy emerged, and despite some successes against the Cretan pirates and an attack on Damiette with 85 ships in 853, Byzantium was largely put on the defensive.

In the west the situation was even more serious. A decisive defeat was the beginning of the Arab invasion of Sicily , which began in 827 and slowly removed the entire island from the control of the empire. This was made much easier by the betrayal of the Byzantine commander Euphemios , who overran the island with the themed fleet to the Arabs. Already in 838 the Muslims crossed to Italy and took Tarento , Brindisi and Bari . Venetian operations against them were unsuccessful, and during the 840s the Arabs raided all of Italy and the Adriatic Sea, including Rome in 846. The southern Italian Lombard duchies and Emperor Lothar I were also unsuccessful in their attempt to drive away the invaders, while two Byzantine attempts to recapture Sicily in 840 and 859 failed miserably. 850 Muslim fleets had become a serious power in the Mediterranean, along with independent Ghazi urged -Piraten Western Christendom and Byzantium on the defensive. At the same time when Byzantium had to wage defensive wars that were costly on all fronts, a new threat emerged: the Rus first appeared on the scene during an attack on Paphlagonia in the 830s and returned in 860 for a major campaign.

Byzantine Reconquest - The Macedonian Dynasty

During the 9th and 10th centuries, the caliphate disintegrated into smaller states and the power of the Arabs waned, allowing the empire to launch a series of successful campaigns against them. This Byzantine Reconquista happened under the rule of the able emperors of the Macedonian dynasty and marked the height of Byzantine power in the Middle Ages.

The reign of Basil I

This triumphal march began with the accession to the throne of Emperor Basil I, who pursued an aggressive foreign policy. Like his predecessor Michael III. he made the Navy a high priority, and military success soon ensued. As early as 867, a fleet led by the droungarios tou plōïmou Niketas Ooryphas ended the Arab raids in Dalmatia and restored the Byzantine presence in the area. A few years later he twice inflicted severe defeats on the Cretan pirates and thus temporarily restored security in the Aegean. Cyprus was also temporarily regained and Bari occupied. At the same time, however, Arab pressure on Cilicia increased again and Tarsus became a major base for attacks against Byzantium by land and sea, particularly under the notorious Emir Yazaman al-Khadim.

In the west, Muslims continued to advance steadily and the local Byzantine militias were too weak to stop them. The empire was forced to resort to the help of its nominal Italian subjects and had to move ships there from the east. After the fall of Enna in 855, Byzantium saw itself limited to the east coast of Sicily and was under increasing pressure. A relief campaign carried out in 868 achieved little, Syracuse was attacked again in 869, and in 870 Malta fell into the hands of the Aghlabids. Muslim pirates ravaged the Adriatic , and although they could be driven from Puglia , they set up bases along the west coast of Italy from which they could not be completely scared away until 915. In 878, Syracuse, the empire's strongest support in Sicily, was attacked and conquered again, mainly because the fleet was busy transporting marble for Basil's Nea Ekklesia in Constantinople. In 880, however, Ooryphas' successor, the droungarios Nasar , won an important night battle against the Tunisians who raided the Ionian Islands . He went straight to Sicily and made rich booty before defeating another Muslim fleet near Punta Stilo . At the same time, another Byzantine squadron won a significant victory near Naples, and these successes allowed Byzantium to launch a brief counter-offensive in the 880s under the command of Nikephoros Phocas the Elder . With them the Byzantine position in Apulia and Calabria could be consolidated, and the subject Langobardia was created, which would later develop into the Katepanat Italy . A heavy defeat at Milazzo, however, marked the end of any major Byzantine naval presence in the following century.

Arab attacks during the reign of Leo VI.

Despite the successes under Basileios, the empire saw itself during the reign of his successor Leos VI. wise exposed to new threats. In the north a war broke out with the Bulgarians under their Tsar Simeon , and in 895 part of the imperial fleet was used to send an army of Magyars across the Danube to devastate Bulgaria. The conflict with Bulgaria brought the empire some serious defeats, while at the same time the Arab threat at sea reached a new height, manifested in constant raids in the Aegean Sea. In 891 or 893 an Arab fleet sacked the island of Samos and captured their stratēgos , and in 898 the eunuch and admiral Raghib took 3,000 Byzantine seamen of the Kibyrrhaiotai away as prisoners. These losses weakened the defenses of the empire and allowed the Syrian fleets to make constant raids across the Aegean. The sack of Demetrias by the pirate Damian of Tire in 901 was a serious blow , and the next year Taormina , the empire's last outpost on Sicily, fell into the hands of the Muslims. The greatest catastrophe, however, occurred in 904, when a fleet under Leon advanced from Tripoli to the Dardanelles and then sacked Thessalonike , the second city of the empire. The Byzantine ships were doomed to stand still because of the overwhelming odds of their opponents, and it is hardly surprising that contemporary naval doctrines ( naumachica ) advocated defensive and cautious action.

The most outstanding Byzantine admiral of this time was Himerios, the logothetēs tou dromou . Appointed admiral in 904, he could not prevent the sack of Thessalonike, but won his first victory in 906. In 910 he made a successful landing near Laodicea in Syria, the city and its hinterland were plundered and devastated without Himerios losing a ship. A year later, however, an enterprise directed against the emirate in Crete failed under his leadership, which transported 43,000 soldiers with 112 dromons and 75 pamphyloi , and on the way back he was ambushed by Leo of Tripoli near Chios , who destroyed the expedition fleet.

It was only after 920 that the tide began to turn. Whether by chance or not, it was exactly in this year that Romanos I Lekapenos ascended to the throne , after Tiberios III. Apsimaros the second (and last) admiral to the throne. As early as 923 Leo was decisively defeated by Tripoli near Lemnos , and with the death of Damian during the siege of a Byzantine fortress, the resurgence of Byzantine naval rule began.

Reclaiming Crete and the Levant

The growing power of the empire was evident in 942 when Romanos I sent a squadron into the Tyrrhenian Sea . With Greek fire it destroyed a fleet of Muslim pirates from the Provencal pirate nest Fraxinetum . An expedition equipped by Constantine VII in 949 to recapture Crete failed completely, probably due to the inability of the commander, Konstantin Gonglyes. Another expedition to Italy was defeated by the Aghlabids in 951 and 952, another attack in 956 and the loss of a Tunisian fleet in a storm in 958 stabilized the situation on the peninsula. With a revolt of the Greeks living in Sicily, a Byzantine expeditionary force was able to regain Taormina, but a heavy defeat of the Byzantine fleet against the Fatimids put an end to the empire's activities at sea. The waters around Italy were left to the local Byzantine forces and the city-states, and it was only after 1025 that Byzantium became involved again in the region.

In the east, the stratēgos Basileios Hexamilites 956 prepared the Muslim fleet of Tarsos a crushing defeat, which enabled a new landing on Crete. The command was given to Nikephoros Phokas , who led a force of 77,000 soldiers against Crete in 960 with a fleet of 100 dromons, 200 Chelandia and 308 transport ships. The conquest of the island removed the direct threat to the Aegean Sea, and subsequent ventures under Nikephoros Phokas also led to the reclamation of Cilicia (963), Cyprus (968) and the northern coast of Syria (969). This eliminated the threat from the Muslim fleets of Syria and restored the empire's naval rule in the eastern Mediterranean. Some raids and naval battles continued when Byzantium found itself at odds with the Egyptian Fatimids in the 990s, however, both sides found a peaceful solution and the Eastern Mediterranean found relative calm for several decades.

Byzantine warships were also active in the Black Sea during the same period: a fleet of the Rus, which threatened Constantinople itself in 941, was destroyed with the help of a hastily assembled defense squadron of fifteen old ships equipped with Greek fire, and the navy also played against in the war the Rus played an important role between 968 and 971, when Emperor Johannes I. Tsimiskes deployed 300 ships on the Danube to prevent the Rus' retreat from Bulgaria.

The Komnen period

Decline in the 11th century

- Admonitions for the emperor, from the Strategikon des Kekänkeos , Chap. 87.

|

For most of the 11th century, the Byzantine Navy had little to do. The threat from the Muslims had subsided, their naval forces were in decline, and relations were particularly good with the Fatimids. The last Arab raid on an area under the empire was reported by the Cyclades in 1035 , but the attackers were defeated the following year. Another Russian attack in 1043 was easily repulsed, and apart from a short-lived attempt to regain Sicily under Georg Maniakes , no major offensive undertakings were carried out. The long period of peace and prosperity led to a climate of overconfidence and a decline in the armed forces. The defense of the Adriatic was entrusted to the Venetians during the reign of Basil II . Under Constantine IX. The army and navy were downsized, as many citizens of the empire bought themselves out of military service and thus led to an increased dependence on foreign mercenaries. The large themed fleets fell into disrepair and were replaced by smaller squadrons that were subordinate to the local military governors. This form of organization was more suitable for fighting pirates than for confronting a well-armed enemy at sea.

In the last quarter of the 11th century the Byzantine navy was only a shadow of itself due to lack of money, neglect and incompetent officers. The writer Kekänkeos lamented in 1078 that "(the Byzantine ships) under the pretext of sensible patrols really do nothing else, when wheat, barley, legumes, wine, meat, oil, large amounts of money and much more "transported from the Aegean islands and coasts while they" flee (from the enemy) before they see him, and so on Shame on the Romans ". By the time Kekänkeus wrote these words, the empire had grown up with new and powerful enemies. To the west, the Norman Kingdom of Sicily , which had driven the Byzantines from southern Italy and conquered Sicily , cast an eye on the Adriatic coasts and beyond. In the east, after the catastrophic Battle of Manzikert in 1071, almost all of Asia Minor, which had previously been the mainstay of the Byzantine economy and military strength, was lost, and the Seljuk Turks had founded their own empire there, the capital of which was Nicaea barely a hundred miles south of Constantinople lay.

Attempts to rebuild under Alexios I and John II.

At that time the deplorable state of the Navy was having dire effects. The Norman invasion could not be prevented and the Norman army occupied Corfu , landed unhindered in Epirus and besieged Dyrrhachium . So began the ten-year war that drained the imperial reserves. The new emperor Alexios I was forced to ask for help from Venice, which had held the Adriatic and Dalmatia against the Normans as early as the 1070s. In 1082 he granted the Venetians extensive trading privileges in exchange for their help. With this treaty and its subsequent extensions, Byzantium practically took itself hostage to the Venetians, and later the Pisans and Genoese acted similarly. The historian John Birkenmeier notes:

"The lack of a Byzantine fleet [...] meant that Venice could claim economic privileges, decide whether enemies could invade the empire, and thwart any attempt by the Byzantines to disrupt Venice's trade or shipping."

In the wars with the Normans during the 1080s, the only effective Byzantine naval force was a single squadron, commanded and possibly maintained by Michael Maurex, a veteran of the old days. Together with the Venetians, he initially retained the upper hand over the Norman fleet, but the united squadrons were taken by surprise and defeated by the Normans near Corfu in 1084.

Alexios undoubtedly recognized the need for his own navy, and despite his busy work on land, he made efforts to build a new fleet. His efforts produced some success, in particular succeeded in thwarting the attempts of some Turkish emirs such as Tzachas of Smyrna to set up fleets in the Aegean Sea. The fleet, under the command of Johannes Dukas, was later used to put down rebellions in Crete and Cyprus. With the help of the Crusaders , Alexios was able to recapture the coasts of western Asia Minor and expand his influence further inland. In 1104 a Byzantine squadron of ten ships occupied Laodicea and some other coastal cities as far as Tripoli . Until his death in 1118 Alexios was able to leave a small navy to his successor John II . Like his father, Johannes focused his efforts on the army and the war on land, but was smart enough to maintain the strength and supplies of the navy. In 1122, however, he refused to extend the trading privileges granted to Venice, and the Venetians then plundered some islands in the Aegean Sea without the Byzantine fleet being able to stop them. Finally, in 1125, John had to confirm the Venetian trading privileges. Obviously the navy was not strong enough to take on the Venetians at this point, and there were many other difficulties that sapped the empire's resources. Not long afterwards, on the advice of his finance minister Johannes von Poutze, Johannes is said to have placed the fleet under the army and canceled its grants, ships were now only equipped for a short time.

Marine expansion under Manuel I.

Under Manuel I , the navy celebrated its resurrection again, and the emperor used it as a powerful foreign policy tool in his disputes with the Latin and Muslim states of the eastern Mediterranean. In the first years of his rule the navy was still weak: in 1147 a fleet under Roger II of Sicily and George of Antioch could devastate Corfu and the Aegean and Ionian islands almost unhindered. The next year Byzantium, with Venetian help, sent an army supported by a strong fleet (allegedly 500 warships and 1,000 transport ships) to retake Corfu and the Ionian Islands. At the same time, however, a Norman fleet of forty ships penetrated as far as Constantinople, demonstrated in the Bosporus in front of the Great Palace and plundered the suburbs of the imperial city. On their return journey, however, the Normans were captured and destroyed by a Venetian or Byzantine fleet.

1155 reached a ten-ship strong Byzantine squadron Ancona , which the Norman rebel Robert III. from Loritello should support. It was the empire's last attempt to win back southern Italy after all. Despite some initial successes and incoming reinforcements under the megas doux Alexeios Komnenos Bryennios, the venture ended in failure and four Byzantine ships remained in enemy hands. By 1169, however, Manuel's efforts for the navy had obviously borne rich fruit, for a large and exclusively Byzantine fleet of 150 galleys , twenty large transport ships and sixty horse transporters under the command of megas doux Andronikos Kontostephanos was sent to attack Egypt together with the Kingdom of Jerusalem . The invasion failed, however, and about half of the fleet (around a hundred ships) was lost in a storm on the way back.

In the wake of the nationwide arrest and incarceration of all Venetians in March 1171, the Byzantine Navy was strong enough to prevent a direct attack by the Venetians, who instead sailed to Chios and tried to negotiate. Manuel sent them a fleet under the command of Kontostephanos, which successfully used delaying tactics until the Venetians, weakened by epidemics, had to retreat and were followed by Kontostephanos' ships. It was a remarkable turnaround considering the humiliation of 1125. In 1176 another 150 strong fleet sailed under Kontostephanos' command to Acre to attack Egypt again together with the King of Jerusalem. However, they turned back after Count Philip of Flanders and many other powerful nobles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem refused to participate in the enterprise. Towards the end of Manuel's reign, however, the effects of years of uninterrupted fighting on all fronts and the emperor's great projects became apparent: the historian Niketas Choniates attributes the increase in pirate activity in the later years of Manuel's government to the diversion of funds intended for the maintenance of the fleet in the imperial budget.

Decline

Under the Angeloi dynasty

After the death of Manuel I and the subsequent decline of the Komnenen dynasty until 1185, the navy quickly fell into disrepair. The maintenance of the galleys and the cost of professional crewing were very high, and neglect could quickly rob the fleet of its combat capabilities. As early as 1182 Byzantium had to hire Venetian mercenaries to man some of its galleys, but in the course of the 1180s, when the Komnenian facilities and crews were still in place, there was talk of undertakings with seventy to one hundred ships.

In 1185 , Emperor Andronikos I was still able to pull together a hundred warships to first keep a Norman fleet in check in the Sea of Marmara and finally destroy it. Nevertheless, the subsequent peace treaty contained a clause in which Sicily was obliged to provide the empire with a fleet. Together with a similar agreement that Isaac II Angelus entered into with Venice the next year, according to which the republic would provide forty to a hundred galleys within six months in exchange for favorable trading conditions, it can be assumed that the inadequacy of the own sea armor was well aware. In 1186 Isaac II sent eighty galleys to Acre to help his brother Alexeius III. Free Angelos who was being held prisoner there. However, the fleet was destroyed near Cyprus by the Norman pirate Margaritus of Brindisi, and a fleet of seventy ships sent to Cyprus the next year to recapture the island from Isaac Comnenus met the same fate. In an attempt to regain some territories in the Holy Land, the emperor also agreed in 1189 to send a hundred galleys to Antioch to assist Saladin in conquering the city.

The decline accelerated in the 1190s. According to Choniates, the then megas doux , Michael Stryphnos, got rich by selling the equipment of the warships for his own account, so that by 1196 only about thirty galleys remained. Byzantium had to watch helplessly as Genoese and Venetians operated unhindered in the Aegean Sea, devastating the coasts and islands and dictating their conditions to the empire. The empire tried to help itself by hiring western privateers to fight for Byzantium. When the Fourth Crusade arrived off Constantinople, only twenty galleys were left, and moreover, they were so rotten that seventeen of them could only be used - unsuccessfully - as fires against the Venetian fleet.

Nikaia and the palaeological period

After the Fourth Crusade , the Crusaders divided the empire among themselves, while Greek successor states emerged, all of which claimed the imperial dignity for themselves. Of these states, the despotate of Epirus and the Empire of Nikaia were the most powerful. Epirus did not maintain any warships, however, while Nikaia initially pursued a policy of consolidation and built a navy for coastal defense. Under John III. Vatatzes foreign policy became more aggressive, and in 1225 the Nika fleet was able to occupy the islands of Lesbos , Chios, Samos and Ikaria . However, they were no match for the Venetians, and in an attempt to block Constantinople, the Nika navy was defeated by a much smaller Venetian fleet in 1235, a similar project also failed in this way in 1241. Nika attempts to instigate an uprising against the Venetians in Crete in the 130s were also only partially successful, so that the last Nika soldiers had to leave the island in 1236. Emperor Michael VIII. Palaiologos was well aware of the weakness of his fleet and therefore concluded the Treaty of Nymphaeum with Genoa in March 1261 , with which he secured their help at sea against the granting of trade privileges.

After the reconquest of Constantinople a few months later, Michael VIII was able to devote himself to building his own navy. Byzantine naval forces were still weak in the early 1260s, as evidenced by the defeat of a combined Byzantine-Genoese fleet of 48 ships against a much smaller Venetian squadron in 1263. In the slipstream of the war between Genoa and Venice, Michael was able to put together a fleet of eighty ships by 1270, which also included some Latin privateers under the imperial flag. In the same year a squadron of twenty-four galleys besieged the city of Oreos on Evia and defeated a Latin fleet of twenty ships. This victory was the first independent Byzantine naval undertaking in a long time and the prelude to an organized campaign in the Aegean that brought many islands back under the rule of the empire - even if only temporarily - during the 1270s.

However, the time of relative strength at sea was soon over. After the death of Charles of Anjou in 1285 and the end of the danger of an invasion from Italy, Michael's successor Andronikos II Palaiologos assumed that he could rely on the strength of his Genoese allies at sea and dissolved the expensive navy. Instead he took fifty to sixty Genoese mercenary galleys under pay. Andronikos found himself exposed to harsh criticism from his contemporaries almost immediately because of the cuts in the military budget, which also extended to the army. The results of this policy soon became evident: during Andronikos' long reign, the Turks gradually brought the entire Anatolian coast of the Aegean under their control, without the empire being able to do anything about it, and one intervened in 1296 and 1297 Venetian fleet to Constantinople and plundered the suburbs unhindered. The historian Nikephoros Gregoras wrote: "If they [the Byzantines] had still owned a fleet, the Latins would never have behaved in this arrogant manner towards them, and the Turks would never have seen the beaches of the [Aegean] Sea ..."

After 1305 the emperor belatedly began to rebuild the navy by putting twenty new ships under construction, but his efforts failed. His grandson and heir Andronikos III. Palaiologos also tried again to restore the strength of the fleet and personally led them on expeditions against Latin possessions in the Aegean Sea, but these efforts failed to slow the general decline. After his reign, the highest number of Byzantine warships named in traditional sources is rarely more than ten, but together with merchant ships confiscated at short notice, fleets of one hundred to two hundred ships could still come into being.

During the civil war of 1341-1347 , the navy was very active and its commander, megas doux Alexios Apokaukos , played a major role. After the end of the civil war, Emperor John VI tried . Kantakouzenos to increase the strength of the war and merchant navy again in order to reduce both the dependence on the Genoese colony in Galata and to block the Dardanelles against the passage of Turkish ships. For this purpose he asked the Venetians for help, but in March 1349 his newly built fleet of nine larger and about a hundred smaller ships got into a storm near the south coast of Constantinople. The inexperienced crews panicked and their ships were either sunk or captured by the Genoese. In 1351, John VI. with only fourteen warships participated in the war of Venice and Aragon against Genoa, but he was soon defeated and had to make an unfavorable peace.

John VI was the last emperor who still had the means to attempt to rebuild a powerful navy. After his reign, the fall of the empire accelerated, which became weaker and weaker due to civil wars and constant territorial losses. It is characteristic of the thinking of the time that the scholar Gemistos Plethon the Despot Theodore II. Palaiologos discouraged in a 1418 memorandum written by the maintenance of naval forces, as the scarce resources were insufficient for the Army and Navy at the same time. During the brief usurpation John VII. In 1390 was Manuel II. Only five galleys and four smaller vehicles (some came from the Knights of St. John in Rhodes) match to Konstantin Opel reclaim his father, John V. to free. Six years later, Manuel agreed to equip ten warships in support of the Nicopolis crusade , and twenty years later he personally commanded four galleys and two other vehicles that had infantrymen and cavalrymen on board and saved the island of Thasos from invasion. In a very similar way, ten Byzantine warships supported the Ottoman pretender Mustafa against Sultan Murad II in 1421.

The last recorded Byzantine naval victory was in 1427 in a battle near the Echinades place when Emperor VIII John. Palaeologus the superior fleet of the Count Palatine of Cephalonia and despots of Epirus , Carlo I Tocco , defeated and forced him thus, all the possessions in the Morea to To cede Byzantium. The Byzantine Navy played its last role in the siege of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II. Fatih , when a mixed fleet of Byzantine, Genoese and Venetian ships (their strength varies between ten and thirty-nine ships) defended against the Ottoman Navy. During the siege, the last surviving Byzantine naval battle took place on April 20, 1453 (nine days before the fall of the city) when three Genoese galleys successfully escorted a Byzantine transport ship through the vastly superior Ottoman blockade fleet and into the Golden Horn .

organization

Early Byzantine Period (4th - mid 7th century)

After the time of the imperial crisis of the 3rd century , Emperor Diocletian strengthened the navy from 46,000 to 64,000 men, a number that is probably the greatest numerical strength of the late Roman navy. By the 4th century, the empire's large, constantly maintained fleets had broken up into many smaller squadrons, and the structure of the naval forces of that time remains unclear in the 4th and 5th centuries. The Danube fleet ( Classis Histrica ) with its legionary auxiliary flotillas is well documented in the Notitia Dignitatum , and its increased activity is mentioned by Vegetius . Some river fleets are still mentioned in the west, but the old standing Praetor fleets have disappeared, and even the remaining fleets of the western provinces seem far too weak and unable to face serious barbarian threats. In the east, it is known that the fleets of Syria and Alexandria existed until around 400, and there is also mention of a fleet in Constantinople itself, possibly composed of the remnants of the Praetorian fleets. However, its strength is not known and it is not mentioned in the Notitia .

For companies in the Mediterranean, larger associations seem to have been put together only briefly in the 5th century and then dissolved again after the end of the campaign. The first standing Byzantine fleet can be traced back to the 6th century, when Anastasius I created a fleet to counter that of the rebel Vitalian. This fleet persisted and developed under Justinian I and his successors into a professional and well-equipped armed force. In the absence of any threat at sea, the navy had shrunk significantly by the end of the 6th century, with several small flotillas on the Danube and two larger fleets in Ravenna and Constantinople. Additional squadrons must have existed in the larger maritime and economic centers of the empire; in Alexandria it was used to escort the grain transports to Constantinople, while that in Carthage watched over the western Mediterranean. The long-established nautical tradition of these regions made it easier to maintain a fleet, and in the event of a larger undertaking, a large force could quickly be assembled by confiscating the numerous civilian merchant ships.

Middle Byzantine Period (late 7th century - 1070s)

Nautical themes

As a reaction to the Arab conquests of the 7th century, the entire military and administrative system of the empire was reformed and the so-called themed constitution was introduced. The empire was divided into several themes , representing regional administrative and military districts. Under the command of a stratēgo , each subject maintained its own military units recruited from the local population. After a series of uprisings through thematic units, the major issues of the early period were divided into smaller districts under Constantine V. At the same time, an imperial army of elite regiments ( tagmata ) was set up, which was stationed in or near Constantinople and, supported by the thematic units, from then on served as the central reserve and core of larger armies.

The Navy went through a similar process. In the 660s, Constans II established the Karabisianoi (Greek Καραβισιάνοι, "men of ships"), possibly from the remains of the questura exercitus or the army of the master of Illyricum . It was commanded by a stratēgos ( stratēgos tōn plōimatōn ) and included the south coast of Asia Minor from Miletus to Seleucia in Cilicia, the Aegean islands and the imperial possessions in southern Greece. The headquarters were originally on Samos, with a subordinate command under a droungarios in Cibyrra in Pamphylia . As the name suggests, it comprised a large part of the empire's standing naval forces and faced the greatest maritime threat: the Arab fleets of Egypt and Syria.

During the Middle Byzantine period, the major themes of the early days were gradually subdivided, and others emerged as the marches of conquest of the 9th and 10th centuries. Although most of the topics with coastal strips had their own ships, there were only three topics primarily devoted to seafaring from the 8th to the 10th century (θέματα ναυτικᾶ):

- The theme of the Kibyrrhaioten or Kibyrrhaiotai (θέμα Κιβυρραιωτῶν) arose from the Karabisianoi fleet , and he was responsible for the defense and administration of the south coast of Asia Minor. The exact time of its creation is unclear, assumptions range from around 690 to after 720. The seat of his stratēgos , first mentioned around 734, was initially in Cibyrra and later in Attaleia . His main lieutenants were the katepano ō the Mardaiten, a ek prosōpou (deputy) in Syllaeum and a droungarios on Kos . As it was closest to the Muslim Levant , it provided the empire's main fleet for centuries until its importance declined with the disappearance of the Arab threat. The fleet is last mentioned in 1043, after which the topic became a purely civil administrative unit.

- The subject of the Aegean (θέμα Αἰγαίου) was separated from the subject of the Kibyrrhaotai in 843, presumably as a reaction to the new threat from the emirate on Crete, and included all Aegean islands except for the Dodecanese .

- The theme of Samos (θέμα Σάμου) was separated from the Aegean theme in 882 and included the Ionian coast with its capital, Smyrna .

In addition, the central imperial fleet (βασιλικόν πλώιμον, basilikon plōimon ) was strengthened in Constantinople and played a prominent role, especially in defending against the Arab sieges of the capital. Because of its main base, it was also known as the Strenon's fleet , after the Greek name for the Dardanelles . In contrast to the Roman fleet, in which the provincial fleets achieved only a small strength and comprised lighter ships than those of the central fleets, the Byzantine themed fleets were probably also combat units of considerable strength on their own.

Other issues with major naval forces were:

- The theme of Hellas (θέμα Ἑλλάδος), which was set up by Justinian II around 686–689 and comprised the imperial possessions in southern Greece with its capital Corinth . Justinian settled 6,500 Mardaites there, who served as rowers and garrison soldiers. Although it was not exclusively dedicated to the navy, it had its own fleet. In 809 it was divided into the smaller themes Peloponnese and the new theme Hellas, which included central Greece and Thessaly . Both then also had smaller fleets.

- The theme of Sicily (θέμα Σικελίας) was responsible for Sicily and the possessions in southwestern Italy ( Calabria ). Once the pillar of Byzantine naval power, it was already very weak in the late 9th century and completely disappeared with the fall of the last Byzantine possession of Taormina around 902.

- The Ravenna theme roughly encompassed the Exarchate of Ravenna until its fall in 751.

- The subject of Kephallenia (θέμα Κεφαλληνίας), which controlled the Ionian Islands , moved from the Archonate to the subject in 809. The new possessions in Apulia were added to him in the 870s, before they became a separate subject Langobardia in 910.

- The theme of Paphlagonia (θέμα Παφλαγονίας) and the theme of Chaldia (θέμα Χαλδίας) were separated from the theme of the Armenian deacon by Emperor Leo V around 819 and received their own naval forces, probably to protect against attacks by the Rus.

Team strength and size

As with its counterpart on land, it is difficult to quantify the exact strength of the Byzantine naval forces and the number of their units and is the subject of numerous debates, not least because of the few and differently interpretable sources. The numbers from the late 9th and early 10th centuries are an exception, for which we have a more precise breakdown that goes back to the campaign against Crete in 911. The lists state that the strength of the Navy during the reign of Leo VI. 34,200 rowers and possibly up to 8,000 marines. The imperial central fleet came to 19,600 rowers and 4,000 marines, who were under the command of the droungarios of the basilikon plōimon . These four thousand marines were professional soldiers who were first set up by Basil I in the 870s. They were of great value to the imperial fleet, as they had previously had to resort to soldiers of the subjects and tagmata for these tasks. In contrast, the new imperial marines represented a better trained and more reliable combat unit that was available to the emperor at all times. The high rank of these soldiers is evident from the fact that they were assigned to the imperial tagmata and were organized in a similar way. The Aegean theme is numbered with 2,610 rowers and 400 marines, the Kibyrrhaeoten fleet with 5,710 rowers and 1,000 marines; the fleet of Samos then comprised 3,980 rowers and 600 marines, while the theme Hellas provided 2,300 rowers and 2,100 of his theme soldiers who were also serving as marines.

The following table provides estimates of the number of rowers throughout the history of the Byzantine Navy:

| year | 300 | 457 | 518 | 540 | 775 | 842 | 959 | 1025 | 1321 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rowers | 32,000 | 32,000 | 30,000 | 30,000 | 18,500 | 14,600 | 34,200 | 34,200 | 3,080 |

Contrary to the assumption often found in lay circles, slaves were not used as rowers, neither by the Byzantines nor by the Arabs or their Roman or Greek predecessors. During the entire existence of the empire, the occupations consisted mainly of free lower social classes who, as professional soldiers, did their legally prescribed military service ( strateia ) in return for money payments or land grants. In the first half of the 10th century, the value of the allocated land is given as around two to three pounds (0.91–1.4 kg) of gold for sailors and marines.

In the year 949, according to Emperor Konstantin Porphyrogennetos , the central imperial fleet alone comprised 100, 150 or 250 warships (the differences result from the possibilities for interpreting the original Greek text). Based on the mean of 150 ships, the historian Warren Treadgold extrapolated, adding the themed fleets, a total navy strength of 240 warships, which was increased from 960-961 to 307 for the Crete enterprise. The latter number is believed to represent the approximate strength of all continuously maintained fleets in the Byzantine Navy (including the smaller squadrons) during the 9th and 10th centuries.

Rank structure

Although the nautical themes were organized very similarly to their land counterparts, there is some confusion in the Byzantine sources as to the exact hierarchy structure. The common term for an admiral was stratēgos , the same term used for generals who commanded matters on land. The stratēgos were subordinate to two to three tourmarchai (roughly vice admirals), who in turn were in command of a number of droungaroi (roughly rear admirals ). Until the middle of the 9th century, the governors of the Aegean and Sami themes were referred to as droungaroi , as their areas of command were split off from the larger themes of the Kibyrrhaoten, but they were later also elevated to stratēgos . The commander of the Imperial Fleet, however, remained known as droungarios tou basilikou plōimou (later with the prefix megas , "large"). His title can still be found in the Komnen period, even if only as the commander of the imperial escort squadron, and survived until the palaeologists' days, when he appears in a "book of offices" of pseudo-codinos from the 14th century. The post of deputy named topotērētēs is also mentioned in connection with the imperial fleet, but his role remains unclear in the sources. He could have held a rank similar to that of a port captain . Although some of these senior officers were professional seafarers who had made their way up from the lower ranks, most of the fleet commanders held high court positions and had to rely on their experienced subordinates for nautical questions.

Since the admirals also acted as civilian governors, they were supported in this capacity by a prōtonotarios , who was in charge of the civil administration of the subject. Other staff officers were the chartoularios, to which the naval administration was subordinate, the prōtomandatōr ("Supreme Messenger"), who acted as chief of staff, and a number of komētes ("counts", analogous to the English count and the French comte ) including the komēs tēs hetaireias , the led the droungarios ' bodyguard . Squadrons of three or five ships were commanded by a komēs or droungarokomēs , and the commander of a ship was called kentarchos ("centurio"), although literary sources give them archaic titles such as nauarchos or even trierarchos .

The crew of each ship consisted of one to three ousiai (ούσίαι, sing. Ούσία; roughly "guard") of 110 men , depending on its size . As officers were subordinate to the commander of the bandophoros ("banner bearer"), who served as first officer, two helmsmen, who were referred to as prōtokaraboi ("heads of the ship") (sometimes they are also called archaic kybernētes ), and a bow officer, the prōreus . Most of these posts were occupied by several officers who took turns in shifts. Most of the officers served up from the crew stand, and De Administrando Imperio speaks of first rowers ( prōtelatai ) who made it to prōtokaraboi of the imperial yachts and later held even higher posts - Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos was safe among them the most prominent. There were also a number of specialists on board, such as B. the two bow rowers and the siphōnatores , who served the siphons used as a launching device for the Greek fire. A boukinatōr ("trumpeter") is also mentioned in the sources, who passed orders to the rowers ( kōpēlatai or elatai ). Since the marine infantry was organized according to the same guidelines as regular army infantry , their ranks were also used for the marines.

Late Byzantine Period (1080s - 1453)

Reforms of the Comnen period

After the decline of the navy in the 11th century, Alexeios I rebuilt the fleet according to new specifications. Since the themed fleets were all destroyed, their remains were combined into a single imperial fleet, whose command was assigned to the newly created office of the megas doux . The megas droungarios of the fleet, once the commanding officer of the entire navy, was placed at his side as his first assistant. The megas doux was also the governor of southern Greece, the area of the ancient Themata Hellas and Peloponnese, which were divided into districts ( oria ), which supplied the fleet. Under John II, the Aegean Islands were also required to maintain, manning and supplying warships, and contemporary sources proudly report that the great fleets of Emperor Manuel were manned by "native Romans", even though mercenaries and allied squadrons continue to be used found. Nevertheless, the fact that the entire fleet was now stationed in Constantinople and that the themed fleets had disappeared also had serious disadvantages, since areas further away, especially in Greece, were now more vulnerable.

Nikaische Navy

With the decline of the Byzantine navy in the late 12th century, the empire increasingly had to resort to the fleets of Venice and Genoa. However, after the sack of Constantinople in 1204, sources already report a comparatively strong fleet under the command of the first Nika emperor Theodor I. Laskaris , although further details are not known. Under John III. and Theodore II , the navy had two primary areas of operation: the Aegean Sea, where operations against the Greek islands (mainly Rhodes) and the transport and supply of armies fighting in the Balkans predominated, as well as the Sea of Marmara, where the Nicaians lay in wait for Latin ships, and Constantinople threatened. For the Aegean Sea, Smyrna was the main base, another in Stadeia was added, while the main base for the Sea of Marmara was Holkos near Lampsakos on the other side of the Gallipoli peninsula .

Paleological Navy

Despite all their efforts, the Nika emperors could not break the supremacy of Venice in the Aegean and Black Seas, so they had to ask Genoa for help. After the reconquest of Constantinople in 1261, Michael VIII set about reducing this dependency by setting up a "national" navy, and created a number of new units for this purpose: the Gasmouloi (Γασμοῦλοι) were men of mixed Greco-Latin descent from the vicinity of the capital, while the Lakōnes (Λάκωνες, "Laconians") or Tzakōnes (Τζάκωνες) were colonists from Laconia and served as marines. They were the foundation of the Byzantine Navy's personnel reserve in the 1260s and 1270s. The rowers, called Prosalentai or Prosēlontes , were also grouped together in a separate unit. Each member of these groups was given a small piece of land to cultivate in exchange for their services, and grouped into small colonies. The Prosalentai received settlements in the coastal areas of the northern Aegean Sea, while Gasmouloi and Tzakōnes mostly found their home around Constantinople and Thrace . These units remained, albeit in reduced strength, for the remainder of the empire's existence (the Prosalentai are mentioned for the last time in 1361, the Gasmouloi around 1422). Throughout the entire palaeological epoch, the main naval base was the Kontoskalion port on the Sea of Marmara in Constantinople, which had been re-dredged and fortified by Michael VIII. Monemvasia in the Peloponnese was probably the most important of the naval bases in the province .

At the same time, Michael and his successors continued the best practice of hiring foreigners in the Navy. In addition to the unreliable Italian city-states, with which the alliances constantly changed, mercenaries were increasingly employed over the past centuries, often rewarded with fiefs for their services . Most of these mercenaries, such as Giovanni de lo Cavo (Lord of Anafi and Rhodes ), Andrea Moresco (successor to de lo Cavo in Rhodes) and Benedetto Zaccaria (Lord of Phocaea ) were Genoese, the most important ally of Byzantium during this period. Under Michael VIII. B. for the very first time a foreigner was given the title of megas doux , namely the Italian privateer Licario , who also received Euboea as a fief. At the same time, the new rank of amiralios (ἀμιράλιος or ἀμιράλης) was introduced, who was third in the naval hierarchy after megas doux and megas droungarios .

Ships

The dromone and its descendants

The most important warship type of the Byzantine Navy up to the 12th century was the dromone (δρόμων) and its related modifications. Apparently they were an evolution of the light Liburnians of the Roman fleets, and the name first appears in the late 5th century to serve as a name for a specific type of war galley in the 6th century. The term dromōn is derived from the Greek word δρομ- (άω) 'run' and thus means something like ' runner ', and authors of the 6th century such as Prokop particularly emphasize the speed of these ships. Over the next centuries, as the dispute with the Arabs at sea increased, heavier versions with two or even three rows of oars developed. Finally, the term was used quite generally for any type of "warship" and was often used freely interchangeably with another Byzantine term for large warships, that of the chelandion (χελάνδιον, formed to kelēs , roughly `` warhorse ''), which first appeared in 8th century appears.

The appearance and development of medieval warships is the subject of heated debate and speculation: until recently, no examples of rowed warships from ancient times or the early Middle Ages have been found, and information about them could only be obtained through the evaluation of written sources, the interpretation of inaccurate visuals and the remains of a few merchant ships are recovered. It was not until 2005 and 2006 that archaeological excavations of the Marmaray project in the area of the Eleutherios port (today's Yenikapi) revealed the wrecks of more than twenty Byzantine ships from the 6th to 10th centuries, including galleys.

The generally held view is that the main developmental steps that distinguished the early dromons from the Liburnians and henceforth characterized medieval galleys, the introduction of a continuous deck ( katastrōma ), the abandonment of the classic ram in favor of a smaller spur above the waterline, and the gradual introduction a Latin rigging . The exact reasons for the omission of the ramspur (Latin: rostrum , Greek: ἔμβολος) remain unclear. Illustrations of upwardly pointing ship's beaks in the 4th century Vergilius Romanus manuscript could indicate that this development had already found its way into the late Roman navy. One possible reason is that the change to the smaller overwater spur occurred at the same time as a gradual further development of the ancient ship construction, in which the hull was first built and then the frame structure was drawn in, towards a method in which the load-bearing parts were built first. The classic ram was very effective against hulls of the traditional construction, while ships built according to the new method were stronger and more flexible and thus less prone to ramming. It seems certain that at the beginning of the 7th century the original purpose of the ram's spur was forgotten, if one can take seriously the comment of Isidore of Seville , who assumed that the ram was a protection against collision with underwater rocks. Some authors have suspected in the past that Latin rigging was introduced by the Arabs in the Mediterranean, who in turn may have brought them from India . With the discovery of new image and text sources in recent decades, however, the scholars have brought the emergence of the Latin sails forward to the late Hellenistic or early Roman era. Not only triangular, but also square Latin sails were known, which for centuries (mostly on smaller vehicles) were used in parallel with conventional rectangular sails. Belisarius's invasion fleet in 533 was probably at least partially rigged in Latin, which makes it likely that Latin sailing had already become standard for the dromons by that time, while the traditional rectangular sail was slowly falling out of use.

The dromons that Prokop describes had only one row of rowers of about 50 oars, with 25 oars on each side. In contrast to the warships of the Hellenistic period, which used outriggers ( parexeiresiai ), the straps of the dromons protruded directly from the side walls. On later double-row dromons of the 9th and 10th centuries, the two rows of oars ( elasiai ) were separated from one another by the deck - the upper row was thus on deck, the lower below deck; and the rowers in the upper row fought together with the marines during boarding maneuvers. The total length of the ships was probably about 32 meters. Although most vehicles this time, only one pole ( histos or Qatar tion led), the larger double-dromons need probably at least two masts in order to effectively maneuver, if it is assumed that a single lateen unmanageable for a ship of this size dimensions would have achieved. The ship was steered with two rudders at the stern ( prymnē ), where there was also the tent ( skēnē ) that protected the commander's bed ( krab (b) at (t) os ). At the bow ( prōra ) there was a raised front fort ( pseudopation ), under which the siphon for hurling the Greek fire protruded - additional siphons could also be led amidships on both sides. A bulwark ( kastellōma ), on which the marines could attach their shields, ran around the entire deck and gave protection to the crew there. Larger ships also had wooden defense towers ( xylokastra ) on either side between the masts, similar to those ascribed to the Roman Liburnians. They served as elevated combat platforms for controlling one's own and opposing ships during boarding maneuvers and provided an excellent shooting position for archers. The bow spur ( peronion ) was supposed to shear off the oars of an opposing ship and immobilize it so that it was helplessly exposed to projectiles and boarding attempts.

By the 10th century, three main types of double-row dromons had emerged, as the detailed records for the Crete ventures in 911 and 949 indicate: the chelandion ousiakon (χελάνδιον οὑσιακόν), named after the number of their rowers, which is 108 almost exactly the one ousia ('guard') corresponded to; the chelandion pamphylon (χελάνδιον πάμφυλον) with a crew of 120–160, whose name either originated in the Pamphylia region or had a handpicked crew (from πᾶν + φῦλον 'all tribes'); and the ordinary dromone with a crew of two ousia . Ships with heavier crews of up to 230 rowers and 70 marines are also described, but they probably only refer to redundant crew members. Smaller, single-row ships, monērēs (μονήρης 'one-row') or galea (γαλέα, from which the name “galley” comes from) with a crew of about 60 were used for reconnaissance purposes and took wing positions in naval battles. Three-row (" Triremen ") dromons are described in a work of the 10th century, which was dedicated to the parakoimōmenos Basileios Lakapenos . This work, which only came to us in fragments, relates to a large extent to descriptions of the appearance and construction of classical triremes and should therefore be treated with caution if one wishes to use it to describe warships of the Middle Byzantine period. The existence of three-row warships, however, is passed down from the navy of the Fatimid Caliphate of the 11th and 12th centuries, and that of Leo VI. The aforementioned large Arab warships of the 10th century could also have been triremes.

For the transport of goods and men, the Byzantines usually confiscated civilian cargo ships for use as troop transporters ( phortēgoi ) or supply ships ( skeuophora ). These ships were mostly sailed and not rowed. Both Byzantines and Arabs used special horse transporters ( hippagōga ), which could either be sailing ships or galleys; The latter with modifications to accommodate the animals. If one assumes that the chelandia originally appears to have been a rowed horse transporter, one can assume that it had constructional differences from the common dromome, whereby the terms in the sources are used indiscriminately alongside one another. While the Dromone was developed exclusively as a war galley, the Chelandie would have had a special cargo hold amidships for the transport of horses, which would have increased its width and hold.

Western models of the last centuries

The exact time at which the dromone was ousted by galleys of Italian origin is unclear. The term remained in use until the 12th century, with Byzantine scholars not distinguishing between the different types. Contemporary Western sources used the term to describe large ships, which were usually transporters, and there is evidence that the new meaning was also adopted by the Byzantines. The description that William of Tire made of the Byzantine fleet in 1169 refers to very large transport ships as "dromons", which are clearly distinguished from the double-row warships, which could indicate that the Byzantines were already using the western types at that time . From the 13th century onwards, the term dromon disappears and is replaced by the word katergon (κάτεργον, roughly "conscripted"), a word from the late 11th century that originally described the occupation that was recruited from the conscripted population . During the late Byzantine period, the Byzantine warships were based on Western models: the term katergon is used for both Byzantine and Latin ships, and the horse transporter Chelandie was taken over by the Western type of Taride (from Arabic ṭarrīda, into Greek as tareta , ταρέτα). A similar process can be observed in sources from Angevin Sicily, where the term chelandre was replaced by taride , with both terms coexisting for some time. Constructive differences between the two types are not mentioned, both relate to horse transporters ( usserii ) with a capacity between 20 and 40 animals.

The double-row Italian galleys remained standard in the fleets of the Mediterranean until the late 13th century, although contemporary sources are usually silent about construction details. From then on, galleys generally became triremes; H. with three men on deck on a single level, each rowing a different oar - the so-called alla sensile system. The Venetians also developed the so-called large galley, which was an enlarged type with more space to carry cargo.

Little is known of the Byzantine ships of this era. The report of a Byzantine delegation who attended the Council of Florence in 1437 and which was written by the Byzantine priest Sylvester Syropoulos and the Greco-Venetian captain Michael of Rhodes reports that most of the ships were of Venetian or papal origin, but it also mentions that Emperor John VIII traveled on an "imperial ship". It is unclear whether this ship was of Byzantine origin or was chartered, and there is no mention of its design. However, it is mentioned that it was faster than the large Venetian merchant galleys that accompanied it, so it was believed to be a light war galley. Michael of Rhodes also wrote a treatise on shipbuilding, which included building instructions and illustrations for both galleys and sailing ships, and which were used by Venice and other seafaring nations in the first half of the 15th century.

Tactics and armament

The Byzantines placed great value on recording and passing on lessons from warfare on land and at sea. These have been summarized in military manuals , and despite their often ancient terminology, these writings form the basis of our knowledge of Byzantine naval affairs. The most important surviving text is the chapters on naval warfare ( peri naumachias ) from the tactica Leos the Wise and Nikephoros Ouranos , the both make strong reference to the 6th century work Naumachiai by Syrianos Magistros and other earlier works. The relevant sections of De administrando imperio by Konstantin Porphyrogennetos and other works by Byzantine and Arab authors serve as a supplement .

Naval strategy, logistics and tactics

When examining ancient and medieval naval operations, it is necessary to first consider the technical limitations of galley fleets. Galleys were not easy to handle in heavy seas and could take over a lot of water due to the waves, which could be catastrophic on the open sea. History tells of countless occasions when galley fleets were lost to severe weather, such as: B. the heavy losses of the Romans in the First Punic War . The shipping season therefore usually extended to the months with good weather from mid-spring to the end of September. The average speed of a galley, even under sail, was limited, as was its ability to carry goods and troops. Drinking water in particular was of paramount importance, and since the rowers used up to eight liters of water a day, the supply of drinking water limited the operational possibilities in the sun-drenched Eastern Mediterranean. Small dromons reportedly could carry enough water for four days. This meant that the galley fleets had to be close to the coast and had to visit the coast regularly to replenish their water supplies and to rest the crew. These circumstances are regularly mentioned in the reports on Byzantine naval operations such as the Belisarius expedition or the landing companies on Crete. For these reasons, Nikephoros Ouranos considers it very important to have experienced seafarers on board, “who have precise knowledge and experience for seafaring [...], which winds stir the water and which blow from the land. You should know both the hidden rocks in the sea and the places with insufficient water depth, the lands to sail along and the nearby islands, the ports and the distances between them. They should also know the country and the water resources to be developed there. "

Medieval naval warfare in the Mediterranean was therefore in the nature of things a fight in the immediate coastal area and on the coast itself, which was waged to conquer the coasts and islands and not to exercise " naval rule " as it is understood today. In addition, with the removal of the ram spur, the only weapon that could reliably sink a ship before the advent of gunpowder and explosive grenades disappeared, so that the fight at sea, in the words of John Pryor, “became more unpredictable. Nobody could still count on being able to achieve a certain success by having a decisive advantage in weapon strength or training level of the crews. ”It is therefore not surprising that Byzantine military manuals place great emphasis on cautious tactics, the primary aim of which is to maintain their own fleet and was collecting reliable intelligence data. The importance of surprise attacks was just as important as the need not to fall victim to them. Ideally, a battle should only be carried out if one could be sure of numerical or tactical superiority. Great importance is also attached to the need to adapt one's own armed forces and tactics to the enemy: Leo VI. lifts z. B. the contrast between the Arabs with their slow and heavy ships ( koumbaria ) and the Slavs and Rus with their small and light vehicles ( akatia , mainly monoxyla ).

For a larger undertaking, the fleet was initially assembled into squadrons in the various fortified bases along the coast ( aplēkta ). Once on the voyage, the fleet then consisted of the main force with the rowed warships and the train ( touldon ) with the sailed and rowed transport ships, which could be sent away in the event of an impending battle. The battle fleet was divided into squadrons, orders were transmitted with the help of signal flags ( kamelaukia ) and lanterns.

An orderly formation was of vital importance on the approach to combat and during the actual fighting. If a fleet got into disarray, the ships could no longer support each other and it would likely lose. Fleets that were unable to maintain an orderly formation or were unable to build up a formation suitable to defend against the opposing order ( antiparataxis ) often refused to fight and withdrew. Tactical maneuvers were therefore mostly aimed at disrupting the opposing formation, including the use of ploys and ruse such as splitting one's own formation with simultaneous flank maneuvers, a fake retreat or hiding a reserve to carry out an ambush. In fact, Leo VI speaks. clearly against direct confrontation and recommends using riot regimes. According to Leo VI. a crescent formation seems to have been common, with the flagship in the center and the heavier ships on the wings to hit the enemy in the flanks. A number of variants of this tactic and suitable defensive maneuvers were available to the admirals depending on the situation.

As soon as the fleets were close enough, they began covering each other with projectiles, from incendiary projectiles to arrows and javelins. The goal was not to sink enemy ships, but to thin the ranks of his crew until one could proceed to the boarding maneuver, which decided the meeting. As soon as the enemy was considered sufficiently weakened, the fleets drew closer, and grappling hooks thrown joined the ships together. The marines and rowers on the upper bank then stormed the enemy ship and went into hand-to-hand combat.

Armament