Social inequality

In sociology, social inequality describes the unequal distribution of material and immaterial resources in a society and the resulting different opportunities to participate in them. The designation can be used descriptively or normatively .

As a normative term, it implies a social criticism ; Social inequality is seen by sociology as a social problem. Social inequality is thus to be distinguished from the more neutral concept of social differentiation and from judgmental concepts such as “social imbalance” and social cuts . Often these terms focus on financial factors (for example, wage cuts, elimination of monetary benefits, changes in social security / social security ).

A lack of intergenerational equity can also be seen as a form of social inequality. Children have no way of combating social inequality; they experience it in their living environment (e.g. neighborhood, kindergarten, school).

General

Certain social groups have different options for using social resources. These differences, known as “social inequalities”, can determine the desires, actions and conflicts of the actors . The causes and characteristics of social inequality can vary and be interpreted differently in different societies and throughout history. The term must not - as is often the case in everyday language - be equated with the term “ injustice ”, although it addresses problems of justice.

Determining factors

According to Stefan Hradil (2001), “social inequality” occurs when people regularly receive more than others from the “valuable goods” of a society (1) than others (2) (Hradil 2001, p. 30).

- Valuable goods: The term refers to “goods” that are considered valuable in a society. The more the individual has of these “goods”, the better their living conditions. "Insofar as certain 'goods' thus [...] represent conditions of life and action that serve to achieve generally widespread goals of a society, they can be considered manifestations of social inequality" (Hradil 2001, p. 28). Such goods can be money, a (non-terminable) job, educational qualifications, living and working conditions or power.

- Distribution: A socially unequal distribution of “valuable goods” in a society exists when one member of society regularly receives more of these goods than another (“absolute inequality”). “In sociological terminology, inequality is always spoken of when“ goods ”that are regarded as“ valuable ”are not distributed in an absolutely equal manner” (Hradil 2001, p. 29).

- Regularly unequal distribution due to the position in the social relationship structure: Not all advantages and disadvantages, not all better or worse positions are manifestations of social inequality, but only those that are distributed in a socially structured, comparatively constant and generalizable form. Their attachment to relatively constant social relationships and positions distinguishes social from other inequalities (Hradil 2001, p. 29).

history

Social inequality exists and has existed in all known societies and is - although it therefore often appears to be natural - always a socially generated fact .

Premodern explanatory models often saw social inequality as being based on facts of nature or the will of a god . So said z. B. Aristotle , free and slaves give it by nature ( physei ). Ancient, like Indian caste society , saw inequalities as natural. Ever since Rousseau's treatise on the origins and foundations of inequality among people in 1755, and at the latest since Karl Marx , the “program of equality” was and is a frequent political goal. According to Karl Marx, social inequality (in his eyes resulting from ownership of the means of production) ultimately leads to the leveling of social differences in a classless society ( communism ). This contrasts with the concepts of liberalism . Adam Smith (1723–1790) was not concerned with the question of equality or inequality; for him, the focus was on overcoming poverty . His main work An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations appeared in 1776.

Social inequality is a consequence of income inequality. Jörg Baten and Ralph Hippe (2017) came to interesting insights into the causes of regional income differences within Europe : They identify the agricultural structures in the 19th century as a decisive factor. The decisive factor is the size of the farms at the time, which in turn was influenced by the nature of the soil. In the smaller farms, the farmers attached greater importance to the fact that their children were educated, as they would later take over the farm. This was u. a. typical for north and north-west Europe around 1900. However, if the soil and climate were favorable for large wheat fields and thus large estates, political elites often developed, which hindered access to education for rural workers. The resulting educational differences had an impact on general economic development.

Effects

Social and Political Impact

The social and political effects of social inequality are widely studied in sociology and political science . They are also the subject of social philosophy , legal philosophy and economics (VWL) and the field of social policy . The macroeconomic effects of unequal distributions are controversial in economics. In political discussions ( economic policy , social policy, family policy, etc.) a positive function of social inequality is asserted. This view assumes that complete social equality cripples competition and reduces the incentive to improve personal performance. Concepts e.g. B. Ordoliberalism and liberal socialism developed ideas here that seek to limit the social inequality seen as worthy of criticism but inevitable in economic policy optimally. The communism , however, necessarily calls for social equality and is based on progress . There should be planning and control processes ( planned economy ) for the allocation of resources with which decisions made should be implemented.

In 1973, Amartya Sen cited a perceived feeling of inequality as a frequent contributor to uprisings in societies.

At the end of the 1990s, the German sociologist Ulrich Beck coined the term Brazilianization for what he assumed was the social change in Europe towards increasing social inequality. Material inequality alone, as an element of social inequality, leads to unequal opportunities for citizens to participate in democracies , i.e. to political inequality . This can be a self-reinforcing and difficult to reverse process.

In his book The Price of Inequality, the American economist Joseph E. Stiglitz highlighted the asymmetrical influence of interest groups on public opinions and perceptions. The top one percent in particular have the means to influence politics for their own benefit through party donations , media control and lobbying .

Economic impact

According to a study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from 2014, faster and sustained economic growth occurs in states that show low inequality after taxes (i.e. usually after redistribution ), in contrast to states with high inequality. In general, redistribution through progressive taxation and government investment in health and education has beneficial effects on economic growth; only in extreme cases is there some evidence that redistribution could have negative effects:

"Still, it would be a mistake to focus on growth and leave inequality to its own devices, not only because inequality might be morally undesirable, but also because the resulting growth might be small and unsustainable."

The OECD notes in its study All on Board: Making Inclusive Growth Happen (2014) states:

“Social inequality undermines people's wellbeing, it hinders economic growth and yet it is more pronounced in many countries than it has been for decades. Political measures aimed at closing the gap between rich and poor will only be successful if, in addition to income distribution, they also take into account access to good education, health and public infrastructure. "

According to the OECD Social Report of May 21, 2015, inequality in the OECD countries has continued to rise and is now higher than ever:

- “Rising inequality not only affects society, it also affects a country's economic prospects, according to the report. If the bottom 40 percent of a society is left behind - including larger parts of the middle class - then economies only use part of their potential. "

And:

- “OECD analyzes show that increasing inequality has no significant effect on formal education and skills of people from relatively wealthy families. For socially disadvantaged families, however, it goes hand in hand with a shorter educational period and often with poorer results in terms of the skills ultimately acquired. "

Because:

- “Our research shows that inequality harms economic growth. So politics not only have social reasons to tackle inequality, but also economic ones. If the governments do not act, then they weaken the social fabric of their countries and, in the longer term, growth as well. "

But:

- “Redistribution via tax and social systems is important here; taken alone, however, it is neither effective nor sustainable. That is why the report also calls for promoting equal opportunities in the labor market, creating high-quality jobs and investing in education and skills. "

- - OECD authors 2015

Social inequality in Germany

In the Federal Republic of Germany, social inequalities are found both between groups of people and in or between certain areas.

Inequality has many dimensions that need to be assessed as a whole. The same facts are therefore assessed differently by economists. In a 2016 interview with economists Marcel Fratzscher and Clemens Fuest , Fratzscher said that in Germany, inequality in life income has doubled over the past 40 years, and inequality in private wealth is the highest in the euro zone. From 2005 to 2015, the inequality of disposable incomes decreased in Germany , which also include state transfers such as the earnings of the unemployed, but not the inequality of opportunities, wages and assets during this period. Since 2000 employees have had to accept real income losses in many cases. Overall, inequality in terms of life chances, social mobility, wealth and income has increased sharply over the past few decades. Fuest emphasized that wealth inequality in Germany had not changed since 2000 and that many unemployed had found a job since 2005. Fratzscher and Fuest disagreed on the extent to which social inequality gives rise to concrete political election decisions.

Distribution of income

The lowest and highest incomes in Germany have diverged since the 1990s, and inequality has increased. At the same time, the middle class has shrunk. While the (annual) average income according to the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) remained largely constant in the 1990s (or even declined by 4.8% in real terms from 2002 to 2005) it rose

- the top 10% by 6%,

- the top 0.01% by 17%,

- the wealthiest 650 Germans by 35% and

- the 65 richest by 53% to € 48 million.

According to social class

According to a study published by DIW in 2008 , the middle class in Germany has been shrinking for years; its share of the total population fell from 62% in 2000 to 54% in 2006. The proportion of the population at the edges of the income distribution has risen accordingly. The share of the income poor (with less than 70% of the annual median income) climbed from 19% in 1996 to 25% in 2006, the share of the high income (with more than 150% of the annual median income) rose from 19% in 1996 to 21% in 2006. In the middle class, downward mobility was therefore more pronounced than the rise to higher income groups. The poorer sections of the population showed a clear consolidation of their condition and thus reduced the chances of moving up to better income classes. A new study by the DIW from 2010 shows a significantly higher relative income poverty than ten years ago. Around 14% of the total population had their disposable income below the risk of poverty threshold. These mainly include households with children and young adults.

By region

In terms of regional income distribution, one can speak of a three-way division in Germany, with a relatively poorest East Germany with around 20% poverty, a middle area in Northwest Germany with around 15% and a relatively richest Southwest Germany with around 11% poverty. Regional taillight is Vorpommern with about 27% poverty rate, while the Black Forest region-Baar-Heuberg in southwestern Germany has only a proportion of 7.4%.

Fair Income - Perception and Reality

According to a survey by the Humboldt University in Berlin on behalf of the Geo magazine , the majority of the population in Germany assumed in the summer of 2007 that “the gap between rich and poor” was widening. The respondents assumed that the average salaries of the CEOs in 2006 were € 125,000 per month, whereby only a monthly income of € 48,000 per month for the CEOs was perceived as "fair". The monthly income of the CEOs of the DAX stock corporations was € 358,000 in 2006, seven and a half higher than the monthly income for CEOs, which is perceived as "fair". In 2007 they rose to € 374,000 and € 391,000 respectively.

Many employees have such a low income that they receive Hartz IV benefits (unemployment benefit II) in addition to their income (“poor despite work”; top- up ). In 2006 this was 1.09 million employees, of which 38.5% were full-time, 14.1% part-time and 47.4% were marginally employed. Many of them work in the so-called low - wage sector (for example as hairdressers, harvest workers , building cleaners), where hourly wages between € 3 and € 6 are paid. In 2006, a total of 5.5 million employees worked for an hourly wage below € 7.50. In 2004 there were still 4.6 million employees (an increase of 20%). In 2006, 1.9 million employees even worked for an hourly wage of less than € 5. Around 75% of all residents in Germany over the age of 18 have a monthly net income of less than € 2,000.

The psychological approach of cognitive dissonance explains that the actual income differences are higher than those assumed by people with low incomes : “He [the person affected] accepts the situation and belittles the injustice. He underestimates his distance to better off - and thus increases his self-esteem. "

Debates on maximum wages (2007)

In December 2007, the unequal distribution sparked a social debate about a maximum wage.

In addition, the disadvantages in terms of wages and salaries that women have to accept are still considerable in most countries of the world. In Germany in 2010 the “adjusted gender pay gap ” (GPG) was around 8 percent. In the new federal states the PG is smaller than in the old ones.

Jakob Augstein stated in July 2011:

“The economy is doing well, many people are not. It has been a long time since the state of the economy showed how people are doing. Today one has little to do with the other. And whoever says that Germany is doing well is already doing politics. Because it conceals the country's biggest problem: social inequality. "

Minimum wage debate (2011)

Following the real estate / financial crisis , the euro crisis and the Greek financial crisis , in autumn 2011 the demand for a minimum wage flared up again in Germany, which is already in place in many euro countries. Even in Germany there are minimum wages as part of collective agreements, but not in legal form. Presumably in view of the 2013 Bundestag election and the considerable electoral slips of the FDP in various state elections, the introduction of a minimum wage was now publicly discussed. The background is also that the state coffers ( national debt ) are empty and minimum wages mean more tax revenue, which does not restore the financial budgets of the ( over-indebted ) state, nursing, health and unemployment insurance and thus also of the (over-indebted) federal states, cities and municipalities , but would relieve.

Effect of taxes

According to Joachim Wieland , increasing sales tax or lowering income and corporation tax changes the ratio of direct taxes to indirect taxes to the detriment of underperforming taxpayers. Since direct taxes (especially through tax progression ) are based on the efficiency principle and, on the other hand, an indirect tax such as sales tax is the same for everyone, in the cases mentioned the tax revenue is shifted to indirect taxes, which do not take into account the financial strength of the taxpayer.

With the lower tax burden on economically more efficient taxpayers (in the years before 2013), tax equity also decreased. The gap between rich and poor increased accordingly.

Influence in political decisions

According to a research report from 2016 on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs , the preferences of social groups are taken into account to varying degrees in political decisions in Germany. Data from the period between 1998 and 2015 were evaluated. There is a clear correlation between decisions on the attitudes of people with higher incomes, but none or even a negative correlation for those with low incomes.

Wealth distribution

A study by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) from November 2007 comes to the conclusion that the distribution of wealth in Germany is even more unequal than the distribution of income :

- the wealth (excluding physical assets and after deducting debts) of all adults is € 5.4 trillion.

- a tenth of all adults own more than 60% of the wealth (3.24 trillion €). Another two-tenths of all adults own 30% of the wealth (€ 1.62 trillion). Overall, three tenths of all adults own 90% of the wealth (4.86 trillion €). (2014: 10% of all households own 65% of the wealth, another 20% of the households 29% of the wealth, i.e. 30% of the households 94% of the Fortune.)

- seven tenths of all adults own only 10% of their wealth (€ 0.54 trillion) (2014: 70% of all households own only 6% of their wealth).

- the richest 0.1 percent of the population in Germany alone accounted for 16% of the wealth in 2015, as much as the bottom 80%.

- In 2015, 1% of the population owned around a third of all assets in Germany, i.e. more than three times as much as the bottom 70% put together.

- the bottom 80% of the population together own less than 20% of the wealth in Germany. (2014: the bottom 80% of the households together own only 16% of the wealth.)

- In terms of wealth distribution in Germany, one can speak of a small upper class (approx. 10%), a small middle class (approx. 20%) and a large lower class (approx. 70%).

- two-thirds of adults have no or very little wealth.

- the average individual net worth in 2002 was around € 81,000. Due to the very unequal distribution, the median , i.e. the value that separates the rich half of the population from the poor, is only around € 15,000.

- Further social structure analyzes show large differences in individual net wealth between men and women (€ 96,000 and € 67,000 respectively) and between people with and without a migration background (€ 87,000 and € 47,000 respectively).

Even more than unevenly distributed incomes, the increasing wealth inequality contributes to social inequality in Germany.

education

Education is one of the most important dimensions of social inequality in today's industrialized societies . While in feudal society the possession of land was important for financial success and social prestige, today economic and social success is almost unthinkable without education. Education therefore plays a central role in inequality research. Various studies have found an educational disadvantage in the Federal Republic of Germany for workers' and migrant children. This inequality was and is criticized by international organizations such as UNESCO , UNICEF , the EU Commission , the OECD and the UN human rights observer Vernor Muñoz .

health

A socially determined inequality of health opportunities is also found. In particular, children from poor households ( child poverty in industrialized countries ), migrants , single women and the unemployed are at a higher risk of developing the disease. The European Union has initiated a two-stage campaign against social inequality in health, which is also supported scientifically, including through specialist congresses on this topic.

Social spatial separation

The socio-spatial separation between poor and rich households is increasing according to a study by the German Institute for Urban Studies . Accordingly, the effects of the housing market (e.g. gentrification ) and the location of socially supported housing are "displacing" households with poor children in disadvantaged neighborhoods, often high-rise areas on the outskirts. The socio-spatial separation that takes place primarily in large cities and urban regions is often described under the terms socio-spatial polarization or socio-spatial segregation .

Social inequality in the UK

According to Oxfam (March 2014), the five richest families own more than the poorest 12.6 million Britons. (in other words, as the poorest 20 percent of the British). Oxfam is pushing UK politicians to do more to tackle tax avoidance and tax havens , and to introduce a wealth tax.

Great Britain's national debt has risen sharply since 2008 (this year a financial crisis began in many countries , which particularly affected the real economy in 2009/10); for 2014 a net new debt of 111 billion pounds, about 7 percent of GDP, is forecast. Average real (= inflation-adjusted) net income has fallen by 6 percent since the beginning of the crisis. The 'Institute for Fiscal Studies' has been publishing statistics and studies on this subject on a regular basis for decades.

Social inequality in the US

The richest 10% of Americans had nearly half the total income in 2007, at 49.7%. In the 1970s the proportion was still 33%. Several studies also show that social mobility in the USA is lower than in Canada, for example, and than in Europe. One of the reasons is the expensive training system.

According to a study by a team led by Raj Chetty , people in the USA at the age of 30 statistically have a higher income, the higher the income of their parents, although this relationship is even closer for men than for women.

Social inequality worldwide

The decrease or increase in social inequality is one of the most controversial topics in inequality research. With the massive decrease in poverty worldwide, inequality has decreased.

Other studies, however, assume that the gap will widen even further worldwide. According to the World Bank's World Development Report 2000/2001, “ inequality varied widely in the 1980s and 1990s ”. Globally, the inequality of income rose between 1960 and 1998 from around 50% to 70%.

Capital:

- In 2006, 1% of the world's population owned more than 50% of the world's total wealth. The richest 10% accounted for around 85% of global wealth in 2014 (as of 2014), but to be among the richest 10% in 2006, wealth of just € 45,780 was required.

- To belong to the richest 1% of the world population it took a fortune of € 375,250 in 2006.

- 50% of the world's population accounts for less than 1% of global wealth.

- Total global wealth was around $ 280 trillion in 2017, according to the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report (up from $ 125 trillion in 2006).

- According to Forbes, the 1645 US dollar billionaires that existed worldwide in 2014 had a combined fortune of approximately 6.5 trillion US dollars. Thus they owned more than 5 times as much as half of the world's population (around 3.5 billion people) put together.

- Together, 70% of the world's population own about 3.3% of the world's wealth.

- According to the “World Wealth Report” 2008, there were around 10.1 million US dollar millionaires worldwide (826,000 of them from Germany). Together, these 10.1 million millionaires (less than 0.2% of the world's population) had $ 40.7 trillion. That was almost a third of the world's wealth.

Income:

- Over 80% of the world's population lived on less than 10 US dollars a day in 2009.

- Over 50% of the world's population lived on less than US $ 2 a day in 2005

- about 1.4 billion people (over 20% of the world population) lived on less than 1.25 US dollars (or € 1) a day in 2008

- In 2005, 48.3% of the world population (3.14 billion people) had an income of less than US $ 2.5 / day and 21.5% of the world population (1.4 billion people) had an income of less than 1, US $ 25 / day. In 1981, 60.4% of the world population at that time (2.73 billion people) had an income of less than US $ 2.5 / day and 42.2% of the world population (1.91 billion people) had an income of less than US $ 1.25 / day. However, the improvements have been achieved almost exclusively in China. In the other developing countries, only the percentages have been reduced (due to the sharp increase in world population), but the absolute numbers have continued to rise.

- The share of the income poor worldwide (less than US $ 3,470 / year) is 78%. The share of the income rich worldwide (with more than 8,000 US $ / year) is 11%.

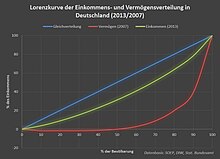

Measure social inequality

Social inequality can be measured. “Measure” is generally understood to mean the assignment of numbers (“measured values”) to objects according to defined rules. The comparison method is used , through which equality or inequality is recognized. The measurement of social inequality can be done at different measurement levels . The degree of unequal distribution is quantified using unequal distribution measures. One example is the Gini coefficient . The simplest measure is the Hoover unequal distribution . Entropy measures such as the Theil index attempt to compare the equalization potentials resulting from unequal distributions in physics and information theory with the effect of unequal distributions of resources in societies.

Political actions for more distributive justice

A number of regional and international initiatives have been launched to politically counteract increasing social inequality. In Great Britain the discussion was driven by the "Equality Trust", which u. a. was founded by British sociologists as a result of their study of the consequences of unevenly distributed wealth . In Germany, the alliance “Redistribute Wealth - A Just Land for All” was formed in 2017, which is organized by unions such as ver.di and GEW , the welfare associations, attac and Oxfam , the BUND for environmental and nature protection and the German Tenants' Association and the like. a. Founded.

See also

- Unconditional basic income

- Marginal tax rate

- Swedish welfare state

- Segregation (sociology)

- Social spatial structure

- solidarity

- Welfare state - a state that takes far-reaching measures to increase the social, material and cultural well-being of its citizens

literature

- Yoram Amiel: Thinking about Inequality: Personal Judgment and Income Distributions , 2000

- Bálint Balla : Sociology of Scarcity. Understanding individual and social deficiencies , 1978

- Eva Barlösius : Struggles for social inequality. Power theoretical perspectives Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften 2004 ISBN 3-531-14311-5

- Monica Budowski, Michael Nollert (ed.): Social inequalities . Zurich: Seismo Verlag, Social Sciences and Social Issues 2010, ISBN 978-3-03777-067-2

- Nicole Burzan : Social Inequality. An introduction to the central theories . 2007, ISBN 978-3-531-15458-9

- Ralf Dahrendorf : About the origin of inequality among people . Mohr (Siebeck), Tübingen ² 1966, ISBN 3-16-517061-4

- James Galbraith : Created Unequal , 1998, ISBN 978-0-684-84988-1

- Alexander Gallas , Hansjörg Herr, Frank Hoffer, Christoph Scherrer (eds.): Combating Inequality. The Global North and South , Routledge , 2015, ISBN 978-1-13-891685-2 ( Look inside )

- Bernhard Giesen , Hans Haferkamp (ed.): Sociology of social inequality , Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag 1987, ISBN 3-531-11897-8

- Karin Gottschall: Social inequality and gender: continuities and breaks, dead ends and knowledge potentials in the German sociological discourse , Opladen: Leske + Budrich 2000

- Alexander Hamedinger: Socio -spatial polarization in cities: Is “neighborhood management” a suitable urban planning answer to this challenge? . In: SWS-Rundschau (42nd year), issue 1/2002, pp. 122-138, Vienna, PDF file in the sws-rundschau.at portal

- Stefan Hradil : Social Inequality in Germany . Opladen: Leske + Budrich 2001

- Ernst-Ulrich Huster: Wealth in Germany - The winners in social polarization , 1998

- Boris Keller: Social Capital and the Illusion of Social Equality. A comparison of Bourdieu, Coleman, and Putnam approaches to explaining social inequality. Scientia Bonnensis, 2007, ISBN 978-3-940766-00-7

- Reinhard Kreckel : Political Sociology of Social Inequality , 3rd, extended edition. Frankfurt a. M./New York: Campus 2004, ISBN 3-593-37598-2

- Niklas Luhmann : Chapter XVI Klassengesellschaft , pp. 1055-1060 (Volume 2) in The Society of Society , 1997, ISBN 978-3-518-28960-0

- Jeremy Saebrook: The No-Nonsense guide to Class, Caste & Hierarchies , 2002, ISBN 978-1-85984-465-6

- Thomas Schwinn : Social Inequality , transcript, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89942-592-5 "social inequality" & f = false

- Amartya Sen : On Economic Inequality , 1973 (Enlarged Edition with a substantial annexe after a Quarter Century with James Foster, Oxford 1997)

- Anja Weiß: Differences that make a difference. Class situations in the theories of Pierre Bourdieu and Niklas Luhmann . , Pp. 208-233 in Nassehi / Nollmann: Bourdieu and Luhmann , 2004, ISBN 978-3-518-29296-9

Web links

- Bernhard Schäfers: Inequality in the concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic

- The fairy tale of the inequality of the century , Clemens Fuest (Ifo Institute for Economic Research) in Die Zeit

- Reinhard Kreckel : Sociology of Social Inequality in a Global Context

- Reinhard Kreckel: Theories of Social Inequality (Lectures 2006)

- Graphic: Distribution of wealth - Germany , from: Facts and figures: The social situation in Germany , www.bpb.de

- Graphic: Income Inequality - Europe , from: Facts and Figures: Europe , www.bpb.de

- Marcel Fratzscher ( DIW ): The elite are closing their eyes (zeit.de December 23, 2016)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wealth and finances of private households in Germany: results of the 2017 wealth survey . In: Deutsche Bundesbank (Ed.): Monthly report . ( online (PDF) ).

- ↑ Everyone is in the middle. In: The time. Retrieved June 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Holger Zschäpitz: Bundesbank study: The fortunes reveal Germany's problems. In: The world. April 15, 2019, accessed June 22, 2020 .

- ↑ After D [etlev] K [rause]: inequality, social. In: Werner Fuchs-Heinritz u. a .: Lexicon of Sociology. 4th edition. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 686.

- ↑ Bernhard Schäfers : Inequality. In: Concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic [1]

- ↑ Eva Barlösius : Equivalent is not the same - ( Memento of the original from June 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Hartmut Esser : Sociology - Special Basics , page 113

- ↑ Hartmut Esser: Sociology - General Basics , page 453

- ↑ Petra Frerichs: Class and Gender as Categories of Social Inequality. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie , Vol. 52, Number 1 / March 2000, doi: 10.1007 / s11577-000-0002-1 .

- ↑ Nicole Burzan: Social Inequality - An Introduction to the Central Theories , page 8

- ↑ Gerd Reinhold, Siegfried Lamnek , Helga Recker: Sociology Lexicon , page 590.

- ^ Martin Greiffenhagen / Sylvia Greiffenhagen: Concise dictionary on the political culture of the Federal Republic of Germany , page 567.

- ↑ Nicole Burzan: Social Inequality. An introduction to the central theories , p. 8.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Müller / Michael Schmid: Hauptwerke der Inequality Research , p. 5.

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education - print version: Concise dictionary of the political system of the Federal Republic (2003) .

- ↑ Baten, Joerg, and Ralph Hippe. "Geography, land inequality and regional numeracy in Europe in historical perspective." Journal of Economic Growth 23.1 (2018): 79-109.

- ↑ ... A perceived sense of inequity is a common ingredient of rebellion in societies ... , Amartya Sen, 1973

- ↑ Ulrich Beck : Full employment - a redefinition of work. The Brazilianization of Western Europe ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Journalistik Journal, vol. 3, no. 1, spring 2001

- ↑ Robert Alan Dahl in the chapters The Presence of a Market Economy (p. 63 ff.), The Distribution of Political Resources (p. 84 ff.) And Market Capitalism and Human Dispositions (p. 87 ff) in On Political Equality , 2006, 120 S., Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12687-7 (Topics of the author, born in 1915, in this book: the foundations of democracy, the importance of political participation for democracy, a scale for the degree the “ polyarchy ”, two future scenarios; categories of the Library of Congress : “1. Democracy, 2. Equality”); German translation: Political equality - an ideal? Hamburger Edition , 2006, ISBN 978-3-936096-72-9

- ↑ Jonathan D. Ostry, Andrew Berg, Charalambos G. Tsangarides: Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth. In: IMF Staffdiscussion Note. International Monetary Fund , February 2014, p. 4, accessed on May 4, 2014 (English; PDF file; 1.3 MB; 320 pages ). Quote p. 25: "It would still be a mistake to focus on growth and let inequality take care of itself, not only because inequality may be ethically undesirable but also because the resulting growth may be low and unsustainable."

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/inclusive-growth/All-on-Board-Making-Inclusive-Growth-Happen.pdf , http://www.oecd.org/berlin/presse/inklusives-wachsen.htm

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/berlin/presse/oecd-sozialbericht-einlösungleichheit-in-deutschland-im-mittelfeld-vermoegensunleichheit-hoch.htm

- ↑ Kolja Rudzio, Mark Schieritz: Rise of the Populists: Is Inequality to Blame? Zeit online, December 15, 2016, accessed March 19, 2017 .

- ^ The 3rd report on poverty and wealth of the federal government. (No longer available online.) In: Bundesanzeiger. June 2008, formerly in the original ; Retrieved August 26, 2008 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c GEO Magazine No. 10/07: GEO survey: What is fair?

- ↑ Shrinking middle class - signs of permanent polarization of disposable income? (PDF; 241 kB) In: DIW weekly report. March 5, 2008, accessed March 9, 2008 .

- ↑ Still high risk of poverty in Germany. Children and young adults are particularly affected. (PDF; 431 kB) In: DIW weekly report. February 2010, accessed February 19, 2010 .

- ↑ Poverty Atlas of the Paritätischer Wohlfahrtsverband. In May 2009, accessed 24 May 2009 .

- ↑ Focus: Salaries of the CEOs of DAX companies [2]

- ↑ - ( Memento of the original from August 23, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Annual Report 2006, p. 45. (No longer available online.) In: Federal Employment Agency. 2007, archived from the original on December 6, 2008 ; Retrieved August 26, 2008 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Thorsten Kalina and Claudia Weinkopf. New calculation of the IAQ on low wages in Germany. Institute for Work and Qualification, University of Duisburg-Essen. (PDF; 91 kB) (No longer available online.) In: Press releases. 2007, archived from the original on November 7, 2011 ; Retrieved August 26, 2008 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ - Statistics monthly net income

- ^ Spiegel: Social imbalance. Germans miss social justice [3]

- ↑ spiegel.de of July 7, 2011: Poor, rich Germany. - Crisis over, economy running, unemployment low. So are you all right? Unfortunately not. The economy is fine, many people are not. All parties must be measured by this.

- ↑ Joachim Wieland: fair taxation instead of national debt | APuZ. Retrieved June 18, 2020 .

- ↑ Lea Elsässer, Svenja Hense, Armin Schäfer: Systematically distorted decisions? The responsiveness of German politics from 1998 to 2015. Ed .: Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (= poverty and wealth reporting of the federal government ). 2016, ISSN 1614-3639 .

- ↑ DIW weekly report: Wealth in Germany is distributed much more unequally than income (PDF file; 329 kB) , November 7, 2007

- ↑ a b Spiegel.de - Inequality in percent

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report March 2016; [4]

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report March 2016; [5]

- ↑ Stefan Bach : Our taxes. Who is paying? How much? For what? , Westend Frankfurt / Main 2016, p. 214 f.

- ↑ Stefan Bach : Our taxes. Who is paying? How much? For what? , Westend Frankfurt / Main 2016, p. 214.

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Report March 2016; [6]

- ↑ Economist Heiner Flassbeck - "The tax system has to be completely readjusted". Retrieved on March 19, 2020 (German).

- ↑ [7]

- ↑ Hartmut Häußermann: The crisis of the “social city” , article from May 26, 2002 in the portal bpb.de of the Federal Agency for Civic Education , accessed on February 16, 2013

- ↑ Antje Seidel-Schulze, Jan Dohnke, Hartmut Häußermann: Segregation, concentration, polarization - socio-spatial development in German cities 2007–2009 . In: Difu-Impulse , 4/2012, ISBN 978-3-88118-507-3

- ↑ spiegel.de March 17, 2014: [8]

- ↑ The Guardian March 17, 2014: Britain's five richest families worth more than poorest 20%

- ^ The Guardian February 5, 2014: Recession has left Britain a much poorer country, says IFS (IFS = Institute for Fiscal Studies)

- ↑ Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2013 (published June 13, 2013), ifs.org.uk: overview; Link list

- ↑ Telepolis : "USA: Income inequality greater than ever" , Florian Rötzer , August 17, 2009

- ↑ "American Dream" in the crisis , orf.at, January 9, 2011

- ↑ Harder for Americans to Rise From Lower Rungs , NY Times, Jan. 4, 2012

- ^ Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Frina Lin, Jeremy Majerovitz, Benjamin Scuder, Working Papers 21936, Childhood environment and gender gaps in adulthood , National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2016. Quoted from: Ben Casselman, Andrew Flowers: Rich Kids Stay Rich , Poor Kids Stay Poor. In: fivethirtyeight.com. February 1, 2012, accessed March 31, 2018 .

- ↑ " Global inequality has fallen sharply ", in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, January 14, 2019. " The rich are getting richer - but so are the poor ", in: Spiegel, June 17, 2017

- ↑ Box 3.5 in Chapter 3 of the World Development Report 2000/2001

- ↑ The percentages are Gini coefficients for a world population divided into three income groups ( http://www.umgabe.de/#global ).

- ↑ Study: One percent of humanity owns half of the world's wealth. In: Spiegel Online . January 20, 2014, accessed June 9, 2018 .

- ↑ a b c spiegel.de: report of December 5, 2006, orf.at: report of December 5, 2006

- ↑ The Gini coefficient is for the global distribution of assets according to these data 85% This is a minimum value because the uneven distribution (i. E. Between the groups within the quantiles ) is not included here.

- ↑ Global Wealth Report 2017 ( Memento of the original from July 12, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Credit Suisse Research Institute, November 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2018

- ↑ http://www.forbes.com/billionaires/

- ↑ n-tv.de: Report from June 24, 2008

- ^ Action by Intel - Report of January 2, 2009

- ↑ Spiegel.de - Report of August 23, 2005

- ↑ zeit.de report of August 27, 2008

- ↑ Shaohua Chen, Martin Ravallion. The developing world is poorer than we thought, but no less successful in the fight against poverty. Policy Research Working Paper 4703, The World Bank Development Research Group, August 2008.

- ↑ United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report. Statistical Annex 2007.

- ↑ Milanovic, Branko and Yitzhaki, Shlomo, 2002. Decomposing World Income Distribution: Does the World Have a Middle Class ?, Review of Income and Wealth, Blackwell Publishing, vol. 48 (2), pages 155-78, June 2002.

- ↑ Schnell, Rainer, Hill, Paul, Esser, Elke: Methods of empirical social research. R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich, Vienna 1999, p. 136

- ↑ Kate Pickett , Richard Wilkinson , “Equality Is Happiness - Why Just Societies Are Better For All,” Tolkemitt at Two Thousand One , 4th Edition, 2010, ISBN 3942048094 .