Banlieue

The French expression Banlieue [ bɑ̃ˈljø ] (female, French , from Latin bannum leucae , literally: " ban mile ") denotes the urbanized areas outside a city center or the outskirts of a large city, which developed in the 19th century in the course of industrialization and urbanization ( Outskirts migration of industrial companies and industry-dependent population) developed or developed. The term is primarily used in France or in relation to the French city system. Likewise, “Banlieue” is used as a synonym for the individual suburbs or for the suburbs ( “banlieues” ) within this peripheral zone.

Since the 1950s, the French state had large housing estates (high-rise estates; cités ) built in the banlieues of the larger cities of France - Paris, Lyon, Marseille, etc. - in which the (mostly low-skilled) industrial workers found comfortable living space for the time. The massive housing shortage in urban areas should be remedied. It was created by a very old and dilapidated building stock in the core cities and war damage . In addition, in the "Trente Glorieuses" (the economic boom of the thirty "golden" post-war years from approx. 1946 to the 1973/1974 oil crisis ), indigenous rural populations and immigrants from French possessions overseas and from other European countries migrated to the industrial conurbations of the country, especially to Paris. Then there was also a sharp rise in the French birth rate after 1945.

The process of de-industrialization that began in the mid-1970s and resulted in a massive layoff of workers in the secondary sector subsequently led to the impoverishment of the proletarian households concentrated in the cités . The cités developed from “centers of modernity” to “places of social decline” and are still characterized by a high proportion of unemployed and welfare recipients, including a disproportionate number of immigrants, some with and some without a French passport. Sometimes these areas are also socially disadvantaged with problems such as crime and drug use.

Since the 1980s there have been repeated (youth) unrest in the cités , which reached a climax in 2005 .

Concept history and definitions

Dated back to the 12th century in its French spelling, "banlieue" - a compound of the Germanic word "Bann" (in French: "le ban" = the spell) and the Latin word "leuga" (in French: "la lieue “ = the mile, see also Leuge ) - in the feudal - monarchical system of rule, the zonal area of a mile around a city, which was still subject to municipal jurisdiction or the authority of the city lords. The establishment of this so-called " ban mile " was primarily based on economic protectionist objectives; urban trade and domestic trade should be protected from competing foreign traders or providers ( ban right ). Against this background, the (gradual) introduction of freedom of trade at the beginning of the 19th century resulted in the loss of importance of the “banlieue” as an economic protection or prohibition zone.

At the same time, the term received a new connotation in the context of the onset of industrialization and the associated urbanization and urbanization in the course of the 19th century , which is the basis of the modern understanding of the term “banlieue” . In the following, the term is used to denote the urbanized areas outside the centers or to denote the peripheral zone of the (large) French cities.

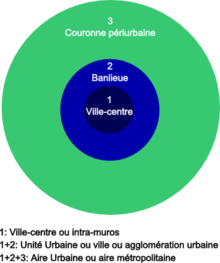

From the side of the spatial science disciplines (spatial planning, geography) the French expression “banlieue” is defined as the “peripheral suburb zone” of an urban agglomeration (primarily in France or the French urban system). "Banlieue" is accordingly the " suburb (zone)", "the surrounding area of a center of large cities", the " suburban district " and / or the " satellite town (zone)". In the model of the urban region, the “banlieue” thus forms the outer edge of the urban agglomeration (city center plus suburban zone ). In the case of the urban region or the greater Paris area, the boulevard périphérique represents the topographical boundary between the core city and the suburban area.

The terminological summary of the individual urbanized areas or communally independent suburbs in the model of the urban region as in the term "banlieue", however, covers the sometimes eminently different nature of the individual areas or suburbs within this zone. Clear differences can be seen with regard to the physiognomic, socio-economic and / or sociological constitution of these communities.

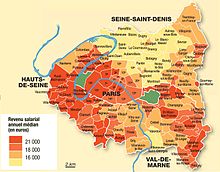

For example, the “Parisian Banlieue” includes, on the one hand, “bourgeois”, “elegant” suburbs in the west of the French capital (e.g. Neuilly-sur-Seine ), which are characterized by an above-average average compared to other municipalities in the agglomeration Household income, homogeneous, wealthy residents who value social distinction (primarily belonging to the upper class and the rich French bourgeoisie) as well as through prestigious residential buildings (such as townhouses - the so-called “ h particôtelulier ”) and luxurious villas with large gardens.

On the other hand, the Paris outskirts also include individual suburbs in the north and east of the "banlieue" (e.g. La Courneuve , Clichy-sous-Bois ), which are made up of terraced and single-family houses for middle-class households as well as high-rise districts or large residential areas with high-rise buildings (so-called . “Cités”), which are primarily characterized by socio-economically weak households (high proportion of social housing in the total housing stock). These cités form structurally weak micro-spaces within the respective suburbs, in which above-average values can be ascertained in terms of the unemployment rate as well as the proportion of recipients of social assistance and social benefits and below-average household incomes (below the poverty line).

Both in scientific publications and in journalistic articles, the term “banlieue” is used as a synonym for a single suburb within the described suburbs of larger cities in France. In the case of reference to several suburbs or suburbs, the plural “banlieues” is used .

Since the 1970s, the conceptual history of the term “banlieue” has also been shortened to “cités” , the large housing estates in some French suburbs, especially on the part of the media and politics . In this context, the term has an increasingly negative connotation and is associated with “ stigmatized problem areas”.

Historical development of the "Banlieue"

19th century - first half of the 20th century

In the course of the industrialization process, different migration flows caused the spatial expansion of the French cities and the emergence of suburbs on the edge of the historic city centers.

The genesis of the “banlieue”, the urbanized areas outside the centers (see above), resulted on the one hand from the migration of some businesses that were formerly located in the city center. The new industrial-mechanical production and distribution methods made a spatial expansion of the production facilities necessary, which could not be realized in the heavily dense historical city centers. The lack of expansion space in the core cities was offset by the locational advantage of the availability of open space on the outskirts, so that numerous industrial companies relocated from the core city to the outskirts. Furthermore, newly founded companies also preferred the peripheral zone.

The outskirts of the larger French cities - Paris , Lyon and Marseille - thus developed into industrial zones in which industrial operations were concentrated. Due to the priority of the state in promoting industrial settlement in the capital region, the local connection to canals and the railroad, mainly in the northern banlieue of Paris, in the area between Paris and the Oise , developed, largely due to the proximity of the Seine bend Valley, “(...) the largest metropolitan area in France for the chemical and metalworking industry; it was called 'the French Manchester' ”.

The resulting resp. The resulting industrial landscapes subsequently act like “magnets” and require the onset of a quantitative, comprehensive rural-urban migration, even if this did not reach the dimensions of similar developments in Great Britain or Germany. The immigrants, who initially came from the French provinces (especially Brittany , Massif Central ), mostly settled in the immediate vicinity of their workplaces; In the banlieue , as early as 1900, numerous new residential quarters or single-family house areas were built as places of residence for the workers. At the same time, the extensive urban redevelopment work carried out by Baron Haussmann and the redevelopment of the core city, in which workers' apartments had to give way to upper-class houses and the few still available inner-city apartments became less and less affordable for proletarian households, had already been emigrating since the 1860s these classes of population into the banlieue result.

The industrialization spurt around the First World War subsequently caused a renewed swelling of the immigrant flows and a further densification of the existing residential areas in the northern and eastern Parisian banlieue as well as a further spatial growth of the same.

Against this background, in the northern, eastern and southern outskirts of the capital, in which industrialization spread or had spread in the form of industrial establishments such as residential areas of the industry-dependent population, around 250,000 - mostly provisional - poor "dwellings" were built in the period from 1920 to 1930 which were set up by workers' households that migrated from the core cities as well as those from the rural regions of the country. In the 1920s, this “zone pavillonnaire” also became the home of numerous immigrants from southern Europe who left their home countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal) for economic hardship (poverty and labor migration) and / or for political reasons (fleeing from the Dictatorships) left or left.

Due to the lack of or only weakly developed urban planning regulation - the settlement in the suburban zone was uncontrolled and uncoordinated - in the predominant part of the suburban zone there was no connection to the core urban supply and disposal (sewerage) and transport infrastructure, so that the hygienic conditions in the Housing estates were blatant.

The catastrophic conditions, especially the sanitary deficits, subsequently became the subject of public discussions. Mainly due to the fact that the communist party took on this problem and, as an “advocate of sanitary reform”, was able to acquire increasing majorities in communities of the banlieue ( “banlieue rouge” or “ceinture rouge” ), which resulted in fears of uprisings and socialist ones on the government side Revolution of the workers' movement (memories of the Paris Commune in 1871), the French government passed a law in 1928 (named "loi Sarraut" after the Interior Minister at the time, Albert Sarraut ), in which an urban planning program (with an emphasis on an orderly Development or containment of the extensive, disordered expansion of the city) as a program for the "sanitation" of the banlieue was called for. The government initiatives that followed were crowned with only modest success; it only succeeded selectively, d. H. in individual communities to improve the hygienic conditions in particular and the living conditions in general.

Development after the Second World War

The emergence of large housing estates (cités) in French suburbs

After the end of the Second World War, there was a massive housing shortage in France, largely due to the war damage and the dilapidated building fabric. It was further accelerated by the ongoing urbanization in the course of the immigration of large parts of the rural population as well as the (labor) migration from other European countries (southern European countries: Spain, Italy, Portugal, Yugoslavia) and from the French overseas territories (former French colonies and Mandate areas in the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa ) as part of the “Trente Glorieuses” (economic upswing in the thirty “golden” post-war years: 1946 to the 1973/74 oil crisis). Since the French state in the immediate post-war period, despite the urgent need for a comprehensive housing policy, concentrated its measures primarily or even exclusively on the reconstruction of the industrial and transport infrastructure, the number of mal-logés ( poorly housed people) grew ) to around eleven million people by the mid-1950s.

“ In the capital the workers lived in miserable conditions. Many apartments had only one room, a third of the apartments were overcrowded, half had no running water and many were dilapidated. Numerous families were accommodated in hotels. Even large parts of the middle class lived in precarious housing conditions. Meanwhile tens of thousands of people, mostly Algerian and other migrants, lived in barracks settlements ( bidonvilles ), which were only disbanded at the end of the 1970s . "

Only the extremely cold winter of 1953/1954 led to a change in state policy in the field of housing, during which numerous fatalities were to be mourned, such as the commitment of Abbé Pierre , who appealed to his compatriots in a radio appeal on February 1, 1954 To provide housing for the homeless. With this impression, the French state subsequently set up a state housing program to alleviate the housing shortage. He saw the construction of large housing estates ( "cités" ) as a suitable means of countering the massive housing shortage in the immediate post-war period. The industrially manufactured large housing estates that were subsequently built in designated urban development areas offered the advantage, from the state perspective, of being able to provide a lot of living space in a relatively short time. For the private, public and semi-public housing companies, economic considerations - such as the moderate costs of this type of construction in relation to the expected high future profits - were in the foreground.

This resulted in some suburbs of major French cities - significantly influenced by the justified already in the 1920s, but only in the post popular nascent concepts of the Bauhaus by Walter Gropius and the urban planning model of Le Corbusier , who in the Athens Charter the had formulated the spatial separation of the functions of living, working, leisure and transport - in the context of social housing construction, pure residential quarters in the form of high-rise towers or blocks ( “ grand ensembles” ), which comprised several hundred, sometimes a thousand identical residential units.

The apartments within these industrially manufactured large housing estates offered - especially in comparison to the condition of the residential buildings or rental apartments in the old stock of the core cities at that time - a high level of comfort at the time (for example due to the presence of modern sanitary facilities), so that here in addition to rural-city hikers and Socio-economically weaker households also settled more socio-economically better-off households of the working class and the middle class who had decided to relocate from the core cities in which the living environment conditions (dilapidated buildings, massive densification of core cities in the urbanization process) had gradually deteriorated.

As a result of the construction of the cités , the number of inhabitants in the corresponding suburbs in the banlieue, in which or on the periphery of which large residential buildings were planned and realized, rose considerably within a very short time. For example, the city of Sarcelles in the north of the Parisian banlieue , which was the first suburb in France to receive a large housing estate, recorded an increase in population from 8,397 to 35,800 in the period from 1954 to 1962 (see chapter on population development in the article Sarcelles ). Row house and single-family house areas of older construction dates such as new high-rise districts now shaped the settlement structure of the corresponding suburbs.

Devaluation and stigmatization of large housing estates since the beginning of the 1970s

While the large housing estates ( cités ) that arose in numerous suburbs of major French cities since the mid-1950s were regarded as attractive residential areas with comfortable living space and facilities, this caused both the deterioration of the poor quality building stock (experimental and rapid construction methods in the period of development) and the deterioration that soon began the conceptually determined lack of supply and leisure opportunities and the inadequate traffic development (road network and connection to the public transport network) a clear loss of attractiveness of the cités as residential locations.

As a consequence, at the beginning of the 1970s, increasing numbers of the socio-economically stronger households migrated from the high-rise estates. On the one hand, they left the cités with the aim of moving to the surrounding area of the cities ( residential suburbanization ), which offered cheap building land with the option of building a home; On the other hand, they moved their place of residence to the central residential districts of the (old) cities, which had undergone a significant upgrade in the course of state renovation measures since the mid-1970s ( gentrification ). The increase in rent levels in the central locations of the cities associated with the inner-city redevelopment and renewal measures, in turn, caused the geographically opposite migration process or the displacement of lower-income households, which in some cases only had the option of "cité" when choosing a residential location.

The process of de-industrialization that began in the mid-1970s , which ended the phase of the economic boom of the Trentes Glorieuses (see above) that had lasted since the end of the war and resulted in a massive layoff of workers in the secondary sector , subsequently led to a pauperization of the proletarian workers concentrated in the cités Households and a further increase in the emigration of wealthier households. As a result, the cités were increasingly characterized by unemployment and poverty.

At the same time, the family reunification made possible as part of the changed state immigration policy , in the course of which, for the foreign workers recruited since the 1950s - who were primarily immigrants from the Maghreb ( see above ), who were initially in transit homes such as Barrack settlements ( bidonvilles ) had found accommodation - the option of having their families join them offered an immigration of these migrant families to the cités , which with their social housing became the refuge for these parts of the population.

Against the background of the outlined development (s), the cités in the banlieue or the banlieues "(...) have been increasingly stigmatized since the 1980s as problem areas, as quartiers sensitive - as places of poverty and decay and from the 1990s - Years as places of insecurity and crime as well as places of (cultural) otherness ”.

Since 1977, the French state has endeavored within the framework of the “Politique de la ville” to promote districts that have socio-economic values that are well below average. The fact that the problems in the cités are far more complex than that they could be solved by urban development measures (e.g. improvement of the building stock, renovation of high-rise buildings) such as the allocation of funds for the social and cultural infrastructure, is proven by the unrest that has been recurring since 1981 cités , which reached a climax in 2005 (see riots in France 2005 ).

On the basis of almost four years of field studies under his guidance, the Islamic scholar Bernard Rougier comes to the conclusion that a parallel society exists here, with a conflict between two opposing worldviews : that of emancipation and enlightenment on the one hand and that of a Salafist understanding of God on the other. Such a phenomenon is sometimes included in France under the negative connotation communautarisme .

See also

Documentation

- From Charlie Hebdo to Bataclan - France's lost youth . Documentation from November 23, 2015, source: WDR .

- The film Swagger , released in 2016, is a documentary about the youth in the banlieues.

literature

On the historical development of the banlieue (s):

- Robert Castel: Negative Discrimination. Youth revolts in the Parisian banlieues . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-86854-201-1 .

- Ronald Daus: Banlieue. Free spaces in major European and non-European cities. Europe: Paris, Berlin, Barcelona . Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-925529-16-0 .

- Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes a. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, pp. 17–25.

- Collective Rage (ed.): Banlieues. The time of demands is over . Association A, Berlin a. a. 2009, ISBN 978-3-935936-81-1 , pp. 59-102.

- Bernhard Schmid: The banlieue problem: The French satellite towns or the ethnicization of the social . In: trendonlinezeitung 2004, No. 12.

- Klaus Schüle: Paris. Foregrounds - backgrounds - abysses. Urban development, urban history and socio-cultural change . Munich 1997, ISBN 3-920041-78-X .

- Luuk Slooter: The Making of the Banlieue: An Ethnography of Space, Identity and Violence. Springer International, Cham 2019, ISBN 978-3-030-18212-0 .

- Jean-Marc Stébé: La crise des banlieues. Paris 2010, ISBN 978-2-13-058271-7 .

- Florian Weber, Georg Glasze a. Hervé Viellard-Baron: Crisis of the banlieues and the politique de la ville in France . In: Geographische Rundschau 2012, issue 6, pp. 50–56.

- Birgit Mennel / Stefan Nowotny (eds.): The languages of the banlieues , transversal texts 2014, ISBN 978-3-9501762-7-8 .

Web links

From the website of the Federal Agency for Civic Education (BpB) (article with a focus on recent developments in the cités, background to the unrest):

- Federal Agency for Civic Education, 2013: Problem area Banlieue. Conflict and exclusion in the French suburbs. ; Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- Federal Agency for Civic Education, 2007: “France's difficulties with the banlieue” ; Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- spiegel.de November 11, 2017: Just before the bang (report)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes u. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, p. 17.

- ^ Heinz Heineberg : Urban geography . Paderborn 2014, p. 47.

- ↑ Bernhard Schmid: The banlieue problem: The French satellite towns or the ethnicization of the social . In: trendonlinezeitung 2004, No. 12.

- ↑ Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes a. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, p. 21.

- ^ Walter Kuhn: The housing market in Paris and its socio-spatial consequences . In: Ludger Basten (ed.): Between Basel, Bochum and Toronto. Insights into the geography of post-industrial urban developments. Berlin u. a. 2011 (= writings of the working group city futures of the German Society for Geography; 11), p. 93.

- ↑ Google Earth 2014.

- ^ Robert Castel: Negative Discrimination. Youth revolts in the Parisian banlieues . Hamburg 2009, p. 23.

- ↑ a b Florian Weber, Georg Glasze u. Hervé Viellard-Baron: Crisis of the banlieues and the politique de la ville in France . In: Geographische Rundschau 2012, issue 6, p. 50.

- ↑ a b Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes u. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, p. 18.

- ↑ a b Ronald Daus: Banlieue. Free spaces in major European and non-European cities. Europe: Paris, Berlin, Barcelona . Berlin 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Alfred Pletsch: Paris: phases of its historical and urban development . In the S. (Ed.): Paris in Transition. Urban development as reflected in school books, science, literature and art . Hamburg 2009 (= studies on international textbook research; 63), p. 38.

- ↑ Ronald Daus: Banlieue. Free spaces in major European and non-European cities. Europe: Paris, Berlin, Barcelona . Berlin 2002, p. 42f.

- ↑ Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes a. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, pp. 17f.

- ^ A b c Alfred Pletsch: Paris: phases of its historical and urban development . In the S. (Ed.): Paris in Transition. Urban development as reflected in school books, science, literature and art . Hamburg 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Christoph Bernhardt: Urban growth between dispersion and integration: The examples of Greater Berlin and Paris 1900–1930 . In: Clemens Zimmermann (Ed.): Centrality and spatial structure of the big cities in the 20th century . Stuttgart 2006 (= contributions to urban history and urbanization research; 4), p. 47.

- ^ A b Christoph Bernhardt: Urban growth between dispersion and integration: The examples of Greater Berlin and Paris 1900–1930 . In: Clemens Zimmermann (Ed.): Centrality and spatial structure of the big cities in the 20th century . Stuttgart 2006 (= contributions to urban history and urbanization research; 4), p. 53f.

- ^ A b c Robert Castel: Negative Discrimination. Youth revolts in the Parisian banlieues . Hamburg 2009, p. 19.

- ↑ Emmanuelle Piriot: The banlieues as a field of political experimentation for the French state . In: Collective Rage (ed.): Banlieues. The time of demands is over . Berlin u. a. 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ a b Emmanuelle Piriot: The banlieues as a political testing ground of the French state . In: Collective Rage (ed.): Banlieues. The time of demands is over . Berlin u. a. 2009, p. 61.

- ^ Robert Castel: Negative Discrimination. Youth revolts in the Parisian banlieues . Hamburg 2009, p. 19 f.

- ↑ a b Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes u. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, p. 18 f.

- ^ Robert Castel: Negative Discrimination. Youth revolts in the Parisian banlieues . Hamburg 2009, p. 20.

- ↑ Emmanuelle Piriot: The banlieues as a field of political experimentation for the French state . In: Collective Rage (ed.): Banlieues. The time of demands is over . Berlin u. a. 2009, p. 62.

- ↑ a b c Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes u. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, p. 19.

- ^ Robert Castel: Negative Discrimination. Youth revolts in the Parisian banlieues . Hamburg 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Robert Castel: Negative Discrimination. Youth revolts in the Parisian banlieues . Hamburg 2009, p. 21f.

- ↑ Florian Weber, Georg Glasze a. Hervé Viellard-Baron: Crisis of the banlieues and the politique de la ville in France . In: Geographische Rundschau 2012, issue 6, p. 51.

- ↑ Georg Glasze, Mélina Germes a. Florian Weber: Crisis of the suburbs or a crisis of society? In: Geographie und Schule 2009, No. 117, pp. 20f.

- ↑ Martin Bohne: Kulturkampf in France Radical Islamists conquer problem areas. In: deutschlandfunk.de. January 22, 2020, accessed January 26, 2020 .