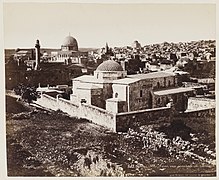

Muslim Quarter of Jerusalem

The Muslim Quarter of Jerusalem ( Arabic حارة المسلمين, Hebrew הַרֹבַע הַמֻוסְלְמִי) is the largest and most populous of the four quarters of the old city of Jerusalem . It covers 31 hectares in the northeast of the old town. In the north and east, the city wall or the outer wall of Haram esch-Sharif forms the border. The Christian quarter borders in the west, the Jewish quarter in the south.

The Muslim quarter has 22,000 inhabitants.

history

Early Roman Imperial Era

The area of today's Muslim Quarter was outside the city limits of the Persian and Hellenistic Jerusalem, but was included in the New Town at the time of Herod (third wall). Different ponds and water reservoirs were characteristic of the use of this area: Struthion ⊙ , Schafteich, Bethesda ⊙ . In ancient times there was a large water basin ⊙ directly north of the Herodian Temple , which was necessary for cult activities. Even after the temple was destroyed, it retained its importance as a water reservoir for the population. The complex was given the Arabic name Birket bani Israel , " Pool of the Sons of Israel ," in early Islamic times.

At the northwest corner of the temple area there was already a castle (Baris) in the Hasmonean period, which Herod had expanded ( Castle Antonia ). This was completely destroyed in the Jewish War, except for the rock pedestal ⊙ on which it was built, and played no role in the following centuries.

Late antiquity, Byzantine and early Islamic times

The Roman destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 represents a deep turning point in the city's history. The newly built road network of Aelia Capitolina is still understandable in the Muslim Quarter, less so in the other three quarters. Two main axes of the late antique and Byzantine city form the borders of the quarter:

- the Cardo maximus (= Suq Chan ez time ) in the west;

- the Decumanus (= Tariq Bab as-Silsila ) in the south.

The Cardo secundus ran in the city valley and lives on in Tariq Al Wad Street , the main street of the Muslim Quarter that runs in north-south direction. There were cross streets between Cardo primus and Cardo secundus, one of which is the Via Dolorosa. But the streets leading east from the forecourt of Damascustor and their cross streets also have late antiquity forerunners.

The Jewish bathing complex in Bethesda was abandoned after the city was destroyed in AD 70; in the 3rd / 4th In the 19th century there was a cult place of Asklepios / Serapis . The Christian Jerusalemites based the story of the healing of the paralyzed man (Jn 5) on the two water basins here. In Byzantine times this local tradition was combined with a (dominating) Marian tradition. A basilica was built in honor of Mary, while the neighboring ancient swimming pool was described by the pilgrims of Piacenza (around 570) as a cesspool. Their severe damage during the Persian invasion led to further decline and finally to the abandonment of the church.

The early Islamic period (638-1099) left hardly any architectural traces in the Muslim Quarter.

Latin Kingdom (1099-1187)

The northeastern part of Jerusalem was sometimes referred to as Judaria or Juvrie during Crusader times , suggesting that a Jewish population lived here from around 1050 to 1099, who were murdered when the city was conquered. Baldwin I settled here in 1115 Syrian Orthodox Christians from the Kerak area . Documents from the Crusader era Jerusalem mention numerous Christians with Syrian names. The "Syrian Quarter" was characterized by church buildings of this Christian denomination, for example:

- St. Maria Magdalena, Church and Monastery. After taking the city, Saladin gave the church building of St. Maria Magdalena to an Amir, who set up the madrasa al-Maʾmunija in it. In ruins since the 15th century, it was built over in 1887 by the Maʾmunija school, which has stood on this site ever since.

- St. Elias. Completed shortly before the Muslim occupation of the city, the church was integrated into the construction of the al-Maulawija mosque .

However, the church landscape in this district was not exclusively Syrian Orthodox. In keeping with older local traditions, the crusaders built a three-aisled church on the site of the Byzantine St. Mary's basilica. It was dedicated to the memory of the legendary parents of Mary, Joachim and Anna. It is known from literature that a noble women's convent belonged to this St. Anne's Church . The inscriptions Sca Anna on several consoles in the Suq al-Aṭṭarin still document that these shops belonged to the Benedictine monastery.

The three-aisled market hall can be easily recognized by its groin vaults as an ensemble of buildings that originated in the time of the Latin Kingdom, when this was the central business area of the city ( Forum rerum venalium ). The central alley ⊙ , today Suq al-Aṭṭarin "Market of the Spice Merchants ", was once called cuisinat ; there were barbers and cookshops for the pilgrims. The western alley ⊙ , today Suq al-Lachamim , "meat market", was the market for herbs, fruits and spices during the crusader era . In the eastern alley, Suq al-Chawadschat " Merchants ' Alley", the Latin (Western European) fabric dealers had their shops at that time.

With Josephus' book on the Jewish War as background information, Theodericus searched for and found Antonia Castle in 1172. All that was left was the solid rock on which the ancient castle had stood. A few years later, the Antonia was identified with the official seat (praetorium) of Pontius Pilate , creating an important constellation for Christian passion piety. The crusaders built a "Chapel of Rest" ( Le repos ) at this point to commemorate the night that Jesus Christ spent in custody (archaeologically proven, later transformed into an Ayjubid cave grave). This is where the Crusader Way of the Cross began and led over the Haram to the Bab al-Qaṭṭanin ⊙ (= Porta dolorosa ) gate and from there on towards the Church of the Holy Sepulcher - a completely different course than today's Via Dolorosa .

Another Christian place of remembrance in the northeast of the city was the house of Herod odes : a chapel from the 12th century (square four-pillar room with crossing dome), almost unrecognizable due to restoration in 1905; today Greek Orthodox Nicodemus Chapel.

Ayyubid period (1187-1260)

After taking Jerusalem, Saladin took measures to give the city a distinctly Islamic character. He initiated construction projects on the Haram . He also claimed two previously Christian building ensembles and converted them into a Sufi settlement ( Tekke ) and a madrasa :

- Chanqah aṣ-Ṣalaḥija (in the Christian Quarter), the former seat of the Greek, then Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, who formed a building complex with the Church of the Holy Sepulcher . Saladin equipped the Sufi convent located here with a bathing facility ( Ḥammam al-Baṭraq , "patriarchal bath ") and other properties.

- Madrasa al-Ṣalaḥija, a law and theological college in the former St. Anne's Church of the Crusaders. In the tympanum of the main portal you can read Saladin's donor inscription, who dates the madrasa to the year 1192/93.

Amir Berke Chan, whose Chwaresmian mercenaries conquered Jerusalem in 1244 and ended a brief interlude of the Crusader rule (1229–1244), received a mausoleum ⊙ ( Turbat al-Amir Berke Chan ) on Kettentorstraße , which shows how strong the formal language of the Romanesque in southern France up to was received in the early Mamluk period. The mausoleum as such is a converted shop vault from the crusader era, as can be seen from the secondary walled pointed arches.

Mamluk period (1260-1517)

Under the rule of the Mamluks, the furnishing of Jerusalem with Islamic buildings continued. Pious foundations or aristocrats acted as builders. The new buildings were mainly built where there was no inner-city development, and since the west side of the Haram was separated from the residential development by a 30-60 m wide, undeveloped strip, this area was ideal for representative building projects. Residential houses of the upper class followed. While there were two western approaches to the haram at the beginning of the Mamluk era, at the end of this period there were eight; this shows how strongly the sanctuary, which was previously just outside the city, was now linked to the residential development.

Construction activity was particularly brisk under the rule of Sultan an-Nasir Muhammad . The Suq al-Qaṭṭanin ⊙ , "Market of the Cotton Merchants ", the largest Mamluk building complex in Jerusalem should be emphasized . It consisted of shops with mostly apartments on the upper floor, as well as two bathhouses ( Ḥammam al-Ain , Ḥammam al-Shifa ) and a caravanserai ( Chan Tankiz ). As the building inscription on the gate wings indicates, the 95 m long market hall was completed in 1335/36 by Saif al-Din Tankiz al-Naṣiri, the governor of Damascus, and was intended to serve as the center of business life in the Mameluk city. The lease income from this market hall was intended to maintain religious institutions in the neighborhood, which the same donor had built in Kettentorstrasse: the Madrasa al-Tankizija (oldest surviving madrasa in Jerusalem, today the Israeli police station), and a quarters for Muslim pilgrims ( Ribaṭ al-Nisaʿ ). The particularly ornate Haram gate Bab al-Qaṭṭanin is closed today and can therefore not be viewed in the context of the souq, but only from the inside.

In the 13th century, Muslims came to believe that Jerusalem was the place of the Last Judgment . For this reason, tombs were built in the city center near the Haram. The oldest example is Turbat al-Amir Berke Chan (1246) on Kettentorstrasse ( Tariq Bab as-Silsila ). At the end of the century, a mausoleum was built right next to the Haram: Turbat al-Malik al-Awhad . A total of eight other Mamluk mausoleums directly border the Haram, and six more are located on Kettentorstrasse.

Jerusalem became an important Muslim pilgrimage destination in Mamluk times. This gave rise to another type of building, the pilgrim hostel (ribat). An example is Ribat al-Mansuri (1282/83) on Tariq Bab al-Nazir Street . The ensemble consists of vaulted rooms of different sizes, which are grouped around a rectangular inner courtyard. Through the portal one enters an anteroom, which is not only a passage to the inner courtyard, but also to a large hall with a rectangular floor plan.

In the Ottoman Empire (1517–1917)

Infrastructure

The outstanding construction project of the Ottoman government was the city wall of Jerusalem . Suleyman I. commissioned the architect Sinan Pascha to do this. In the years 1537 to 1541, the old town wall, which is over 4 km long and has 35 towers or wall projections, was built on remains of the Crusader and Ayjubid wall.

The water supply was also improved by repairing the water reservoirs of the ponds of Solomon and the Birket es-Sultan ; this corresponds to representative fountains in the city. A total of thirteen Ottoman wells have been preserved in Jerusalem, six of which were donated by Suleiman himself.

Similar to Nablus , there was a flourishing soap industry in Jerusalem in the 16th century, but it deteriorated more and more into the 19th century. The soap industry had settled at the Suq Chan ez period (“market for olive oil”), and there is also the only architectural monument of an Ottoman soap factory ( maṣbana ) in Jerusalem at no Remains of two stoves and chimneys can be seen.

Christian sites

If you compare historical maps of Jerusalem, you can see that the number of Christian pilgrimage sites increased significantly in the period from 1870 to 1930. Many were newly created. Numerous European Christians have visited Jerusalem since the 1840s. European governments supported Christian building projects that were also built in the Muslim quarter because there was building land there, e.g. B. on Tariq al-Wad Street. Titus Tobler wrote about them: "Now it is one of the most deserted streets, although easily accessible for the Franks."

- Flagellation Chapel (Flagellatio), 2nd station on Via Dolorosa. Ibrahim Pascha handed the site over to the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land in 1838 , and with financial support from Duke Max Joseph in Bavaria , adjacent properties were acquired. The new building of the Flagellatiokapelle (1839) included walls from the Crusader era.

- Austrian hospice for the Holy Family , near the 3rd station on Via Dolorosa. The large plot of land in the Muslim quarter made a representative building possible that would not have been possible in the small Christian quarter. The Austrian Vice Consul Josef Graf Pizzamano described the advantages of the property in 1854: “Austria would have such a proud building in Jerusalem, where every nation makes every effort to own a hand's breadth of land and Austria has so far nothing, despite the large amount of Austrian money that arrives here. "

- Ecce Homo Basilica : Marie-Alphonse de Ratisbonne acquired land on the Via Dolorosa in 1856, to which no Christian traditions adhered at the time. Excavations took place in the 1860s and a type of bricolage technique was used to create a new pilgrimage tradition that brought three elements together: parts of a Roman arched monument called “ Ecce Homo ”, a piece of ancient pavement called Lithostrotos, and an ancient cistern identified with the Struthion reservoir mentioned by Flavius Josephus . A new pilgrimage site in the monastery of the Zion Sisters was created with the approval of the church.

- St. Anna: The Turkish pasha of Jerusalem donated the church ruins to the French consul Napoleon III in the name of Sultan Abdülmecid I. as thanks for the support in the Crimean War . The former crusader church served as a madrasa from 1192/93 to 1761, since then it has been unused. Christophe Édouard Mauss restored church and crypt. In 1878 the French government left the facility to the White Fathers .

Jewish sites

The large Jewish population in this part of the old town had their own religious institutions. So there was a Kollel Hungarian Jew named Schomrei haChomos ⊙ (שומרי החומות "keepers of the walls"), the students of the Chatam Sofer had founded in 1862 and received its own teaching building in the street Tariq al-Wad in the 1870s. Against resistance from the Turkish authorities, the parishioners built an upper floor as a prayer room in 1904, and from then on the ground floor was dedicated to the 24-hour Torah study, in which the students took turns in shifts.

In the 19th century, the Jewish businessman Mosche Wittenberg bought a house ⊙ on Tariq al-Wad Street. Due to a lack of space, the street was spanned with a stone vault, as has been the case several times in the old town, and the living rooms were built above it. The building was used alternately, as a hotel, synagogue, library. Jews lived here until the riots of 1929.

Consulates

The French consulate was initially located in the Christian Quarter, but was then moved to the Muslim Quarter, near the Damascus Gate. The Austrian consulate was a little further south.

population

The Ottoman administration divided Jerusalem into neighborhoods (the well-known "quarters" of the Old City are a simplified model that was popularized by pilgrimage and travel guide literature, but represents a view from the outside). The demarcation and naming of the neighborhoods was in constant change.

The 1905 census gives the number of families by neighborhood and religious affiliation for the (approximate) area of today's Muslim Quarter as follows:

| neighborhood | location | Jews | Muslims | Christians |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ḥārat Bāb al-ʿAmūd | East of the Suq Chan ez time | 15th | 112 | 469 |

| Ḥārat as-Saʿdīya | Then to the east to the Herodestor | 1 | 161 | 124 |

| Ḥārat Bāb Ḥuṭṭa | North-east corner of the old town | 7th | 595 | 12 |

| Ḥārat al-Wād | On both sides of Tariq Al Wad Street | 388 | 383 | 91 |

There are several neighborhoods of ethnic minorities in the Muslim Quarter, and various theories exist about their immigration to Jerusalem. According to one thesis, they are descendants of contract workers who, during the British mandate, e.g. B. were recruited to build railways; Others see in them descendants of Mecca pilgrims who wanted to visit the Muslim shrines in Jerusalem as part of the Hajj and stayed there. Among them are Africans from areas of origin in Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan and Chad, who traditionally worked as guardians of the haram. Today they live in the historic pilgrimage quarter Ribat al-Mansuri , which was an Ottoman prison for death row inmates and execution site during the Arab uprising of 1914–1917. Other neighborhoods are Palestinians with an Indian, Afghan, Moroccan or Domari background.

British mandate (1917–1948)

The British administration placed the old city of Jerusalem practically a listed building. New buildings were not permitted, only renovations for which modern building materials such as asbestos, steel beams or corrugated iron roofs were prohibited. The old town should retain its traditional architectural character with the typical flat domed roofs. Upgraded as a “holy city”, the old town developed in the direction of an open-air museum. It was a Protestant vision of the Holy City, which was to be experienced as the place of activity of Jesus of Nazareth and the first Christians. A “cleaning” of later, especially Ottoman architecture therefore seemed necessary - paradigmatic for this is the uncovering of the old town wall by demolishing residential houses built on it.

The ever-precarious water supply in Jerusalem was addressed from the very beginning of the British administration. In order to improve the water quality, she gradually replaced the cisterns with a network of water pipes. In order to fight malaria, it was necessary to remove breeding grounds for mosquito larvae. That concerned z. B. the ancient water reservoir Birket bani Israel in the Muslim quarter. After archaeological research made it clear that it was not the biblical site of Bethesda, the pond lost interest and was filled in for hygienic reasons in the 1930s.

At the site of the ancient Antonia Castle (= 1st station of the Via Dolorosa) there was an Ayjubid madrasa, later a Mameluk governor's seat, which was converted into a barracks under Ibrahim Pasha in 1835. The British authorities tore down the barracks and built the ʾ Umarija elementary school on the site in 1923/24 . During the construction work, Louis-Hugues Vincent examined the crusader era chapel Le repos in 1920 . The building was in three parts: an inner chamber that bordered the Herodian wall of Antonia and probably represented the prison of Christ, a small vestibule and a vestibule; the latter collapsed in an earthquake in 1927. The rest is still there and serves as an office for the school.

Other European states reduced their previous commitment to Christian sacred buildings in Palestine during the mandate, with the exception of Italy. This period is characterized by brisk Roman Catholic church building, mostly according to plans by the Franciscan architect Antonio Barluzzi. In 1927/28 he restored the Flagellatiokapelle (= 2nd station of Via Dolorisa) in the Muslim Quarter so comprehensively that the small remains of an apse dating from the Crusader era can no longer be identified. A. Gerardi designed the western front and the portal with a mix of Crusader-era architectural motifs, apparently inspired by illustrations in a work by Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé about the churches of the Holy Land (1860).

Jordanian administration (1948–1967)

in the 1920s Bertha Spafford Vester (American Colony) founded a children's hospital in Ḥārat as-Saʿdīya, halfway between Damascus and Herod's Gate. After 1948 it was the only such facility for the residents of Jerusalem's Old City. Opposite, directly at the old town wall (Ibn Jarah st.), There was a camp of the Jordanian army, the only open space in the densely built Muslim quarter.

Israeli administration (since 1967)

The Muslim Quarter is overpopulated. The legal status of East Jerusalem offers advantages in the Israeli labor market, particularly in the wake of the Oslo Accords in the 1990s. That is why Palestinian families do not move to the West Bank, even if they live very cramped in the old city of Jerusalem, and especially in the Muslim Quarter. This is at the expense of the historical building fabric. Typically, kitchens or sanitary facilities are built in the inner courtyards and on the roofs without building permits. Fearful of losing their homes in the event of a renovation, Palestinian families often do not apply for such measures for which the funds are actually available. Some houses have also been locked since the owners fled into exile in 1967, and with no way of returning they invest nothing in the decaying buildings.

Attempts to establish an Israeli-Jewish presence in the Muslim Quarter are concentrated on the main street of this neighborhood: Tariq Al Wad . This street runs parallel to the wall of the Haram and has always been used by Jews and Christians for religious reasons. For Orthodox Jews from the western part of Jerusalem who enter the Old City through the Damascus Gate, it is a direct route to the Western Wall; for Christians, a short stretch of Via Dolorosa runs along this street. At the same time, tourists are less to be found here, and the residents dominate the streetscape.

The Wittenberg House ⊙ , confiscated as "enemy property" under Jordanian administration, has been held in trust since 1967, and since 1986 by a trust called Wittenberg-Hekdesch, backed by the Ateret Kohanim organization. She settled Jewish families in the Wittenberg House, and it developed into a center of the Jewish community in the Muslim Quarter. Ariel Sharon , who was a member of the cabinet at the time, moved into his second home here in 1987.

In 2008 the Roi House was inaugurated, named after Roi Klein, who died in the Second Lebanon War and was built with financial support from the US businessman Irving Moskowitz. Since the children of the Jewish families who moved in here cannot play on the street, there is a secure playground for them on the flat roof of the house.

The Ohel-Jitzchak Synagogue on Al-Wad Street refers to the Kollel Schomrei haChomos, completed in 1904 . A hundred years later, the Ateret Kohanim organization began renovating and expanding the building, which was inaugurated as a synagogue in 2008 and has been managed by the Western Wall Heritage Foundation ever since . From Ateret Kohanim's point of view, the synagogue is the center of a Jewish community in the Muslim Quarter. Because of its proximity to the Western Wall and the direct vicinity of the historic Maghrebian district (now Western Wall Plaza) that was demolished by Israel in 1967, this project has potential for conflict. Groups of Israeli soldiers regularly visit the Ohel Yitzchak Synagogue, which is known as an information event.

Attractions

- much of the Via Dolorosa ,

- the St. Anna Church ,

- the pool of Bethesda ,

- the flagellation chapel ,

- the condemnation chapel ,

- the Ecce Homo Basilica ,

- the Austrian pilgrim hospice and

- the Antonia Castle .

literature

- Johannes Becker: Locations in the old city of Jerusalem: life stories and everyday life in a narrow urban space . transcript, Bielefeld 2017.

- Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 . Magnes Press, Jerusalem 2001.

- Max Küchler : Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Guide to the Holy City . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, SS 207–220. 311-408. 518ff. 534-537.

- Nimrod Luz: The Mamluk City in the Middle East: History, Culture, and the Urban Landscape . Cambridge University Press, New York 2014.

- Nimrod Luz: Reconstructing the Urban Landscape of Mamluk Jerusalem: Spatial and Social-political Implications . In: Reuven Amitai, Stephan Conermann (Ed.): The Mamluk Sultanate from the Perspective of Regional and World History . V&R unipress, Göttingen 2019, pp. 126–148.

- Alexander Schölch : Jerusalem in the 19th century (1831–1917 AD) . In: Kamil Jamil Asali (ed.): Jerusalem in history . Olive Branch Press, New York 1990.

- Scott Wilson: Jewish Inroads in Muslim Quarter . Washington Post , February 11, 2007

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 312 f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 1117.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, pp. 325–334.

- ^ Katharina Galor , Hanswulf Bloedhorn: The Archeology of Jerusalem: From the Origins to the Ottomans . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2013, p. 180 f.

- ^ Adrian J. Boas: Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City under Frankish Rule . Routledge, London / New York 2001, p. 88.

- ^ A b Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 349.

- ↑ Four of these inscriptions are in situ, another was used during the restoration of the church in the tympanum of the western main portal. See Denys Pringle: The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem . Volume 3: The City of Jerusalem . Cambridge University Press, New York 2007, p. 154.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 334 f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 521. Klaus Bieberstein : On pilgrims' tracks. A stroll through the Jerusalem of the Crusaders . In: World and Environment of the Bible 3/2003, pp. 8–13, here p. 10.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 357.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 348.

- ↑ Nimrod Luz: Reconstructing the Urban Landscape of Mamluk Jerusalem: Spatial and Social-political Implications , Göttingen 2019, p. 141.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 482.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 336.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 212 f.

- ↑ Nimrod Luz: Reconstructing the Urban Landscape of Mamluk Jerusalem: Spatial and Social-political Implications , Göttingen 2019, pp. 141 f.

- ^ A b Andrew Petersen: Dictionary of Islamic Architecture . Routledge, London / New York 1996, p. 136.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 218 f. 536 f.

- ^ Katharina Galor, Hanswulf Bloedhorn: The Archeology of Jerusalem: From the Origins to the Ottomans . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2013, p. 228 f.

- ^ Katharina Galor, Hanswulf Bloedhorn: The Archeology of Jerusalem: From the Origins to the Ottomans . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2013, p. 215.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 98 f.

- ^ Katharina Galor, Hanswulf Bloedhorn: The Archeology of Jerusalem: From the Origins to the Ottomans . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2013, p. 241 f.

- ^ Amnon Cohen: Economic Life in Ottoman Jerusalem . Cambridge University Press, New York et al. 1989, p. 152.

- ↑ Vincent Lemire : Jerusalem 1900: The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities . University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London 2017, p. 52.

- ↑ Tituus Tobler: Topography of Jerusalem and its surroundings . Volume 1: The Holy City . Berlin 1853, p. 202.

- ↑ a b Denys Pringle: The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem . Volume 3: The City of Jerusalem . Cambridge University Press, New York 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Helmut Wohnout: The Austrian Hospice in Jerusalem: History of the pilgrim house on the Via Dolorosa . Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2000, p. 33 f.

- ↑ Vincent Lemire: Jerusalem 1900: The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities . University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London 2017, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Max Küchler: Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Travel Guide to the Holy City , Göttingen 2007, p. 336.

- ↑ Dovid Rossoff: Where Heaven Touches Earth: Jewish Life in Jerusalem from Medieval Times to the Present . Guardian Press, Jerusalem 1998, p. 345 f.

- ^ A b c Nir Hasson: The Street That Encapsulates Jerusalem . In: Haaretz , November 11, 2015.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 58.

- ↑ Johannes Becker: Locations in the Jerusalem old town: life stories and everyday life in a narrow urban space , Bielefeld 2017, p. 118.

- ^ Ilan Ben Zion: The Old City's African secret . In: The Times of Israel, April 6, 2014.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, pp. 179-181.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, p. 188.

- ^ Kathryn Blair Moore: The Architecture of the Christian Holy Land: Reception from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance . Cambridge University Press, New York 2017, p. 294.

- ↑ Ruth Kark, Michal Oren-Nordheim: Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948 , Jerusalem 2001, pp. 138 f.

- ↑ Denys Pringle: The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem . Volume 3: The City of Jerusalem . Cambridge University Press, New York 2007, p. 134.

- ^ The Spafford Childrens' Center: History .

- ^ The Jerusalem Foundation: Spafford Community Center - Abna El Quds .

- ^ John Reed: Jerusalem: City of ruins . In: Financial Times , October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Wendy Pullan, Maximilian Sternberg, Lefkos Kyriacou, Craig Larkin, Michael Dumpe: The Struggle for Jerusalem's Holy Places . Routledge, London / New York 2013, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Wendy Pullan, Maximilian Sternberg, Lefkos Kyriacou, Craig Larkin, Michael Dumpe: The Struggle for Jerusalem's Holy Places . Routledge, London / New York 2013, p. 173.

Coordinates: 31 ° 47 ' N , 35 ° 14' E