Khodja Mahschad

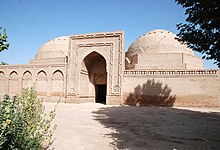

Chodscha Mahschad ( Tajik Хоҷа Маҳшад , Russian Ходжа Машад ), also Chodscha Maschad, Khoja Mashad , is one of the oldest madrasas in Central Asia from the 9th to 12th centuries, which was preserved near the city of Shahritus in the province of Chatlon in southwest Tajik . The restored brick building consists of two domed rooms connected by a portal vestibule; the eastern one is possibly based on a mausoleum built in the 9th century. The complex is one of the most important historical monuments in Tajikistan and was included in the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage in 1999 .

location

Coordinates: 37 ° 13 ′ 12.6 ″ N , 68 ° 8 ′ 53.1 ″ E

From Shahritus, the A384 expressway coming from the state capital of Dushanbe , which is 165 kilometers away , leads further downstream on the right (western) bank of the Kofarnihon to the south to Amu Darya on the border with Afghanistan and along this to Termiz in Uzbekistan . Chodscha Mahschad is six kilometers south of Shahritus on this road, which after another twelve kilometers reaches the small town of Aiwanj (Ayvaj) on the Amu Darya. Five kilometers south of Shahritus the road passes a cemetery with the remains of the Chodscha Sarbos mausoleum (Хоҷа Сарбоз) from the 11th / 12th. Century; after another nearly kilometer, a side road branches off at a school to the east into the center of the village of Sajod (Саёд, Sayyod). The village ( kishlak ) Sajod is the capital of the sub- district of the same name ( jamoat ) of the Shahritus district. After a few 100 meters through the village on the left, you will reach the historic complex at the end of a park with flowers and trees. The adjacent farms are surrounded by vegetable gardens and fruit trees and separated from the road by high walls.

The area in the extreme southwest of Tajikistan is known as the Kubodijon (Qabodiyon) oasis. These include the Kubodijon and Schahritus districts on the Kofarnihon and Nosiri Chusraw (formerly Beschkent) along the Uzbek border. In the broad valley on the lower reaches of the Kofarnihon around the cities of Kubodijon and Schahritus, over 100 historical and cultural sites have been listed, the mostly small remains of which are hardly known. The first archaeological explorations took place between 1946 and 1948. In 1966 the Dushanbe Historical and Archaeological Institute researched the medieval buildings of the lower Kofarnihon Valley. Two mausoleums were made of burnt bricks , the majority of the buildings were made of adobe bricks . These include the ruins of Chodscha Durbod (Хоҷа Дурбод, Khoja Durbad) south of Schahritus, a small square mausoleum made of baked bricks, and the slightly larger, also square mausoleum Tillo Khaloji near Aiwanj. The local population places votive offerings in its upright walls. The pilgrimage site of Chilu-chor chashma ("44 sources") has been worshiped eight kilometers west of Shahritus allegedly since early Islamic times . According to some Arabic sources, the lower Kofarnihon still belonged to the Tocharistan region in the Islamic Middle Ages .

historical development

The first Arab conquests in the regions of Tocharistan and Balkh south of the Amu Darya took place at the time of the Umayyad caliph ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān in the middle of the 7th century. North of the Amu Darya, in the areas of ancient Transoxania (Arabic mā warāʾan-nahr ), the Arabs advanced on a campaign to Sogdia as early as 654 and in 681 Arab troops stayed for the first time in Transoxania over the winter. A few limited forays took place in the intervening years. The Persian historian at-Tabarī (839–923) is one of the main sources for the conquests and the spread of Islam in Central Asia, which was formerly influenced by Buddhism and Zoroastrianism in the 8th and 9th centuries . In the second half of the 8th century there were several uprisings by syncretistic sects influenced by Shiite Islam and Zoroastrianism . Various regional dynasties stood in the 9th / 10th. Century under the rule of the Samanids and in the 10./11. Century of the Seljuks .

The oldest known mosque in the region was built in the second half of the 9th century in Balkh, the former center of Zoroastrianism. The surviving remains of the No Gumbad Mosque show a square building with a side length of 20 meters, the space of which was divided into nine segments by arcades that spanned four mighty brick columns in the center. The oldest mosques in Bukhara date back to the 10th century.

For the first three Islamic centuries, scholars taught in mosques. To accommodate teachers and students, hostels ( han ) were built near the mosques . When classes took place in their own buildings from the 10th century, the madrasa often belonged to a complex with a mosque and a mausoleum; the functional differentiation from the mosque was also small and the madrasa could also serve as a prayer room.

The architecture of the madrasa developed from the end of the Abbasid Caliphate in the eastern Iranian highlands . In Khorasan , Transoxania and Northern Iran, madrasas emerged under the Ghaznavids at the beginning of the 10th century as a further development of teaching in mosques and in the private homes of teachers. Madrasas later came to Syria from the east. W. Bartold recognized the Central Asian Buddhist monastery ( vihara ) as the origin of the madrasa architecture , roughly corresponding to the excavated complex of Adschina-Teppa based on the four- iwan plan . Just as possible, but also unsecured, is André Godard (1951), the derivation of the house style characteristic of Khorasan. A madrasa built under the Samanids in Bukhara was destroyed by fire, presumably because it was mostly made of wood. From the 11th century onwards, madrasas were built in Central Asia from materials that have stood the test of time. Shortly before 1046 , Sultan Tughrul Beg had the first Seljuk madrasa built in Nishapur (northern Iran) in order to spread Sunni teachings and reduce the influence of the Shiites . The oldest famous madrasa - famous because a Nizāmīya ( al-Madrasa al-Niẓāmīya ) founded by Nizām al-Mulk , the vizier of the Seljuks, in Baghdad in 1067 - probably goes back to forerunners in Khorasan and Bukhara, where it is according to contemporary historians there were already 33 madrasas before. From the 10th to the 12th centuries, numerous madrasas were created between Bukhara, Merw (Turkmenistan), Nishapur, Ghazni (northern Afghanistan) and Chuttalan. The latter region roughly corresponds to the present-day Tajik province of Chatlon. According to the Persian historian Abu'l-Fadl Bayhaqi (995-1077), over 20 madrasas (including Chodscha Mahschad) existed there. Contemporary sources report several hundred madrasas for Balch, which existed until the Mongols conquered the city in 1220. Of the madrasas in the Chuttalan region, only Khodja Mahschad survived. This is the only surviving of the numerous madrasas of the 11th / 12th centuries from the entire Seljuk rulership. Century, whose architecture is otherwise not known. In addition to the madrasas built in Samarkand under the Qarakhanid ruler Abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn Nasr (Ibrahim I, r. 1052-1068), Chodscha Mahschad is probably the oldest preserved madrasa of all. The earliest preserved madrasa in Iran is the Madrasa-i Imami in Isfahan from 1325.

architecture

The main building of Chodscha Mahschad consists of two mighty structures vaulted by domes on a square base, which are connected to one another by a gate. A single square domed structure, like the one that remained in ruins in the neighboring Chodscha Sarbos, formed the architectural basis for the Central Asian tombs from the 9th century (Persian gumbaz , Arabic qubba ). Basically, a mosque was never suitable as a burial site, the prayer room and the burial room had to be functionally separated. When many new mausoleums were built in the 11th century with the spread of Sufism , the obligation arose to add another room for prayers ( ziarat. ) In addition to the burial chamber ( gur-chana , from gur , “grave” and chana , “room”) -chana, from ziarat, “to commemorate”, “honor”) or to read the Koran ( dars-chana , from dars, Arabic “lesson”, “teaching”).

Little is known about the history of Khodscha Mahschad. The eastern domed structure was possibly laid out in the 9th century as a mausoleum with several graves. Chodscha Mahschad would then have been an important place for the spread of Islam in the region. In the 11th century, according to this temporal assessment, the western part of the building was added as a mosque. At the beginning of the 11th century, the Persian poet, traveler and missionary Nāsir-i Chusrau (1004-1072 / 78) is said to have received lessons here. The place was a mausoleum, mosque, madrasa and developed into a medieval pilgrimage center. R. Mukimov dates the remaining eastern building to the 11th century and the western extension to the 12th century.

The area of the former entire complex was 68 × 48 meters, the two restored domed buildings together measure around 33 × 15 meters on the outside and around 12 meters high. Each of the rooms is 10.4 × 10.4 meters. In addition, there is a front façade on the entrance side in the south, which protrudes several meters over the building on both sides. The façade is not statically connected to the building wall and towers above the dome. The connecting room with a high Iwan portal forms the central axis in a south-north direction. Almost the same size, the two domes differ in some details of their structure and ornamentation. The outer wall of the eastern rectangular substructure consists of double rows of tiles that are interrupted by a raised truss and laid in a central bond. At the upper edge of the eastern square building ends on three sides with a frieze , which is formed by an inclined row of bricks and above a diamond band. The south facade of the western domed building consists of a series of ogival blind arcades , which after the restoration are filled with bricks in a herringbone pattern and in different diamond patterns, as they were in the 11th / 12th. They were common in the 19th century. The Iwan facade is designed with two circumferential and knotted, double bulges. Originally, the entire space in between must have been decorated with delicate floral patterns, a remnant of which has been preserved at the bottom right. The other outer walls do not have any architectural decorations.

The eastern dome was erected as a free-standing building with entrances in the east wall and the west wall. Inside, two rows of simple grave sites made of piled up clay indicate the function of the building. The transition from the square of the lower wall to an octagonal link is made with small trumpets in the corners and above deep, ogival niches. A high round dome rises above. Small gussets with protruding bricks lead to their base circle in the corners. The western domed building is empty inside. Opposite the only entrance, a prayer niche ( miḥrāb ) is deepened in the west wall . The vault construction corresponds to the eastern part of the building.

In the north of the building, small remains of the mud brick wall have been preserved. They belonged to a series of barrel-vaulted rooms facing an inner courtyard with Iwane in the axes and towers at the corners. The 3.5 to 4 meter long, narrow rooms in the madrasa served as accommodation ( chudschra , also hudschra , khujra ) for the students. With such a facility it is quite possible that it served as the center ( chāneqāh ) of a Sufi brotherhood ( ṭarīqa ) in which Sufis lived, practiced religious rituals ( ḏikr ) and gathered pilgrims. An old cemetery extends behind the complex.

Several state administrative bodies, including the Ministry of Culture, the administration of the Shahritus district ( nohija ), the Sajot sub-district ( jamoat ) and the Sajot mahalla committee, take care of Khodja Mahschad as one of the most important monuments in the country . Independently from each other, Iran and the United States have provided substantial financial aid to rebuild the facility since 2005. From 2005 to 2009 the American embassy in Dushanbe supported the reconstruction project with a cultural program that included the preservation of Sarasm , Old Punjakent , the promotion of the documentation of archaeological sites and Tajik music .

Before the start of the reconstruction, the subsidence and cracks on the foundation caused by different groundwater levels had to be removed with the help of a drainage system. The groundwater, which comes partly from the Kofarnihon and is increased by winter rains, occurs at a depth of 2.2 to 4.2 meters near Chodscha Mahschad. The maximum is reached in summer and the minimum in winter. Work began in 2005 with the construction of a drainage system and the static securing of the existing wall remains. Then the western and later the eastern dome and finally the facade of the Ivan were restored. In July 2010 the restored domed buildings were officially presented to the public.

Cultural meaning

The name of the site is made up of chodscha , a Muslim honorary title in Central Asia, and the name of the northern Iranian city of Mashhad . Legend has it that Chodscha Mahschad was a rich man who came from Iran at the end of the 9th century to found a madrasa here. The mausoleum in which the preacher was later buried is said to have been built by birds overnight by the will of Allah. According to another assessment, however, the place was founded as an Islamic teaching center.

The population of the Kubodijon oasis is ethnically mixed. Although most of the residents see themselves as Tajiks , a distinction is made between the mahalli , who have lived here for centuries, and the agricultural workers from other areas of Tajikistan ( kuhistoni ) and from Uzbekistan who settled in the 1950s for the cultivation of cotton . The mahalli (“indigenous” population) are divided into Tajiks, Arabs (descendants of the Arab immigrants) and sajodis (who trace their descent back to the Prophet Mohammed ). The kuhistoni (Persian kohistan, kuhiston , "land of mountains"), who came from the mountains, established their own settlements alongside the mahalli . For the mahalli , Sajod is one of the oldest settlements in the region. Cotton cultivation is the main source of income around Sajod , so the village's mahalla committee plays a leading political role in the sub- district.

The ethnic groups in the Sayod Sub-District carefully construct their legends of origin and trace back to various eminent men. The mahalli , who see each other in a family relationship, distinguish themselves in particular from the kuhistoni . While the kuhistoni regularly go to their region of origin (often the Rasht Valley ) to practice their religion to reassure their group membership , the mahalli worship the holy places in the area. They include around Shaartuz the "44 springs" ( Tschilu-Chor Chashma ) and the tombs of the "Seven Saints" ( "seven chodschas ", Persian way chodschagan ) including Khoja Sarbos and Khoja Mahschad.

The mahalli in the environment of Khoja Mahschad, so the Chodschamahschadi , their origins - of a legend according to - back to people in Mashhad, which should have come to the region with the earliest spread of Islam. These people would have converted the locals who followed the "pagan fire cult" (Zoroastrianism) to Islam and founded the place Sajod. The families belonging to this origin belong to the Sajodi descent group (Arabic silsila ), take the village name as evidence and derive privileges from it. In the debate about the importance of Khoja Mahschad are the Chodschamahschadis who believe the site created exclusively for their families from a mausoleum, the other mahalli groups compared to, for it is a miraculously overnight Resulting sanctuary for all mahalli is . Residents of the village know from their childhood in the first half of the 20th century that in Chodscha Mahschad, not religious ceremonies, but secular New Years celebrations ( Nouruz ) and certain wedding celebrations were held. It was only after 1960 that, according to the statements, the religious leader of the place (a pīr ) forbade women to hold their wedding celebrations here. This narrative fails to take into account the fact that Khodja Mahschad has always been a religious center. In return, all residents of Sajod agree that the tombs behind Khodscha Mahschad belong to members of the Khodschamahschadis . The tombs in the eastern domed structure come for the Chodschamahschadis from the first Muslim missionaries, other groups refer to archaeological investigations that are supposed to prove pre-Islamic burial rituals.

literature

- Hafiz Boboyorov: Collective Identities and Patronage Networks in Southern Tajikistan. (ZEF Development Studies) Lit, Münster 2013

- K. Baypakov, Sh. Pidaev, A. Khakimov: The Artistic Culture of Central Asia and Azerbaijan in the 9th – 15th Centuries. Vol. IV: Architecture. International Institute for Central Asian Studies (IICAS), Samarkand / Tashkent 2013

- GA Pugachenkova : Transoxania and Khurasan . In: CE Bosworth, MS Asimov: History of Civilizations of Central Asia. The age of achievement: AD 750 to the end of the fifteenth century. Volume IV. Part Two: The achievements. UNESCO, Paris 2000

Web links

- Khoja Mashad Complex . Wonders of Tourism

Individual evidence

- ↑ Mausoleum of Khoja Mashkhad . UNESCO tentative list

- ↑ Hafiz Boboyorov: Collective Identities and patronage networks in Southern Tajikistan, p.176

- ↑ Alijon Abdullayev: Groundwater and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Tajikistan (Kabadian Valley). In: Proceedings of the Regional Workshop "Ground Water and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Central Asia. Samarkand / Bukhara, Uzbekistan, June 14-18, 2000, p. 41

- ↑ K. Baypakov, Sh. Pidaev, A. Khakimov: The Artistic Culture of Central Asia and Azerbaijan, pp. 116f

- ^ Robert Middleton, Huw Thomas: Tajikistan and the High Pamirs . Odyssey Books & Guides, Hong Kong 2012, p. 220

- ^ W. Bartold , CE Bosworth: Ṭuk̲h̲āristān . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Volume 10, 2001, p. 602

- ↑ Étienne de La Vaissière : Sogdian Traders. A history . ( Handbook of Oriental Studies . 8th section: Central Asia , Volume 10) Brill, Leiden / Boston 2005, pp. 265f

- ^ Masjid-i No Gumbad. ArchNet (Photos)

- ↑ Klaus Fischer : Central Asia: Afghanistan, Transoxanien, Turfan . In: Hans-Thomas Gosciniak (Hrsg.): Brief history of Islamic architecture . DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1991, p. 307

- ↑ J. Pedersen: Madrasa. Islamic studies in the mosque: the early period . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Volume 5, 1986, p. 1124

- ↑ Rabah Saoud: Muslim Architecture under Seljuk Patronage (1038-1327). Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilization (FSCE) 2004, p. 8

- ^ André Godard: L'origine de la madrasa, de la mosquée et du caravansérail à quatre īwāns. In: Ars Islamica, Vol. 15/16, 1951, pp. 1-9

- ↑ GA Pugachenkova, AH Dani, Liu Yingsheng: Urban Development and Architecture. In: CE Bosworth, MS Asimov: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, p. 523

- ^ John D. Hoag: Islam. (World history of architecture) Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1986, p. 103

- ↑ AK Mirbabaev: The Islamic Lands and Their Culture. In: CE Bosworth, MS Asimov: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, pp. 38f

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1995, p. 174

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Madrasa. III. Architecture . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . Volume 5, 1986, p. 1137

- ↑ GA Pugachenkova: Transoxania and Khurasan . In: CE Bosworth, MS Asimov: History of Civilizations of Central Asia, p. 524

- ↑ Sergei Khmelnitzkij: The Mausoleum of Muhammad Bosharo . In: Muqarnas, Volume 7, No. 1, 1989, pp. 23-34, here p. 29

- ^ Reconstruction at the Khoja Mashhad Madrassa and Mausoleum, Shahrituz.

- ↑ R. Mukimov: Tajikistan . In: K. Baypakov, Sh. Pidaev, A. Khakimov: The Artistic Culture of Central Asia and Azerbaijan in the 9th – 15th Centuries, p. 116

- ↑ R. Mukimov: Tajikistan . In: K. Baypakov, Sh. Pidaev, A. Khakimov: The Artistic Culture of Central Asia and Azerbaijan in the 9th – 15th Centuries, p. 116

- ↑ Khoja Mashad Complex . ( Memento of the original from January 27, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Wonders of Tourism

- ↑ Hafiz Boboyorov: Collective Identities and patronage networks in Southern Tajikistan, p.183

- ^ Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation . ( Memento of the original from January 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Embassy of the United States, Dushanbe, Tajikistan

- ↑ Alijon Abdullayev: Groundwater and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Tajikistan (Kabadian Valley). In: Proceedings of the Regional Workshop "Ground Water and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Central Asia. Samarkand / Bukhara, Uzbekistan, June 14-18, 2000, p. 42

- ↑ Mausoleum of Khoja Mashhad opens its door to visitors. ( Memento of the original from January 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Khovar, July 2, 2010

- ↑ Hafiz Boboyorov: Collective Identities and patronage networks in Southern Tajikistan, pp 176-180

- ↑ Hafiz Boboyorov: Collective Identities and patronage networks in Southern Tajikistan , S. 186, 190