Chodja Sarbos

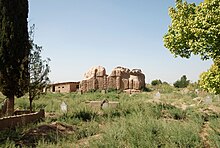

Chodscha Sarbos ( Tajik Хоҷа Сарбоз , Russian Ходжа Сарбоз ), also Khoja Sarboz , is a mausoleum of the 11th / 12th centuries that has been preserved as a ruin made of adobe bricks . Century near the city of Shahritus in southwest Tajikistan . It belonged to the widespread early type of square one-room domed buildings in a form characteristic of southern Tajikistan.

location

Coordinates: 37 ° 13 ′ 51.3 ″ N , 68 ° 8 ′ 11.9 ″ E

From the small town of Shahritus on the right (western) bank of the Kofarnihon , the A384 expressway leads south in the wide valley of the Kofarnihon to the Amu Darya , which forms the border with Afghanistan , and along this river downstream to Termiz in Uzbekistan . The distance from Shahritus to the small town of Aiwanj (Ayvaj) on the Amudarja is 18 kilometers, to Khodscha Sarbos it is 5 kilometers on this route. The ruin is in a large cemetery west of the road behind trees and cannot be seen from the road. To the south of a plantation with apricot trees, at the end of the low surrounding wall of the modern cemetery, an asphalt road branches off, on which the entrance gate of the cemetery is reached after 200 meters. To the south, between bushes and trees along the expressway, some houses belonging to the village of Sajod (Саёд) follow. The center of Sajod is 1.5 kilometers further and east of the road.

The oldest preserved and the only restored medieval building on the lower reaches of the Kofarnihan around Kubodijon and Schahritus is the Madrasa Chodscha Mahschad (Хоҷа Маҳшад) in Sajod: a domed building made of fired bricks, which was built in the 11th / 12th centuries. Century is dated. Other, in most cases little-known remains from the Islamic Middle Ages around Shahritus include Chodscha Durbod (Хоҷа Дурбод, Khoja Durbad), a small square mausoleum made of baked bricks south of Sajod and the slightly larger, also square mausoleum Tillo Khaloji in the Near Aiwanj. The local population places votive offerings in its upright walls. A total of over 100 historical and cultural sites were listed. In the Islamic Middle Ages this area belonged to the Tocharistan region .

architecture

In the 8th and 9th centuries, the Arab conquest and Islamization in southern Central Asia brought about far-reaching social upheavals. In early Islamic times, in the 7th and 8th centuries, according to statements in the Koran, the worship of saints and thus the building of mausoleums was not allowed. The graves of Islamic personalities should be simple. At the beginning of the 9th century, the ban on building family graves was broken for the first time. The Samanids built the first tomb in Central Asia in Bukhara . Then mausoleums (Persian gonbad , Arabic qubba ) developed into one of the main Islamic architectural genres. The building of mausoleums over the graves of prominent political leaders and Islamic saints was promoted in Central Asia, especially under the Qarakhanids , after they declared Islam the state religion in the 11th century. Basic for the architectural style of the mausoleums in Samanid times was the square building consisting of one room and covered by a dome. For the possible origin of this type of building, reference is made to pre-Islamic residential fortresses ( keschk ) built outside of cities . These were monumental two-storey buildings with a residential floor standing on a high platform. Examples are the Sogdian palace fortress Tschilchudschra and the Urtakurgan castle there. Another connection could be to the mausoleums from the 1st millennium BC. Exist: the burial grounds Tagisken-Nord (9th to 8th century BC) and Ujgarak on the lower reaches of the Syrdarja in the province of Qysylorda ( Kazakhstan ) with mausoleums made of mud bricks, Qoy Qırılg'an Qala (4th century BC) BC, in Khoresmia ) and Hirik-Rabat (3rd century BC, on Syr Darja in the desert of Qysylqum, Kazakhstan). The square domed building is next to the circular or polygonal tower one of the two basic forms of Iranian mausoleum architecture and is on as this fire temple serving Chahar Taq the Sassanian attributed time.

Chodscha Sarbos consisted of massive adobe walls on a square base. The entrance portal ( peschtak ) was on the northwest side. The mausoleum represents a special South Tajik architecture school of the 11th / 12th centuries. Century, which is characterized by wide rectangular niches in the middle of the inner walls. The walls were partially preserved up to the level of the trumpets , which led in the corners to the octagonal link below the dome. The remnants of the wall are mostly bricked in horizontal layers and plastered with clay, only the south-east wall consists of rows of alternating inclined bricks in the area of the niche. The dome has disappeared.

The mausoleum was dedicated to one of the seven holy brothers. The part of the name chodscha is a traditional Muslim honorary title in Central Asia. Some chodscha trace their lineage ( silsila ) back to the prophet Mohammed via Fatima bint Mohammed and her husband Ali . Sarbos refers to a regular infantry soldier of the emir in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan .

Today's ruin is exposed to the weather unprotected, it suffers from erosion from strong winds and temperature fluctuations between hot summer and cold winter months. Judging by a row of concrete post foundations running around all four sides, a roof was planned. Adjacent to the west is a new memorial building made of brick walls with a flat roof. The room houses a venerated tomb made of rammed earth that has been whitewashed with a lime plaster. Corn kernels are offered in a hollow at one corner of the tomb.

literature

- K. Baypakov, Sh. Pidaev, A. Khakimov: The Artistic Culture of Central Asia and Azerbaijan in the 9th – 15th Centuries. Vol. IV: Architecture. International Institute for Central Asian Studies (IICAS), Samarkand / Tashkent 2013

- GA Pugachenkova : Transoxania and Khurasan . In: CE Bosworth , MS Asimov: History of Civilizations of Central Asia. The age of achievement: AD 750 to the end of the fifteenth century. Volume IV. Part Two: The achievements. UNESCO, Paris 2000

Individual evidence

- ↑ K. Baypakov, Sh. Pidaev, A. Khakimov: The Artistic Culture of Central Asia and Azerbaijan, pp. 116f

- ^ Robert Middleton, Huw Thomas: Tajikistan and the High Pamirs . Odyssey Books & Guides, Hong Kong 2012, p. 220

- ↑ Alijon Abdullayev: Groundwater and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Tajikistan (Kabadian Valley). In: Proceedings of the Regional Workshop "Ground Water and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Central Asia. Samarkand / Bukhara, Uzbekistan, June 14-18, 2000, p. 41

- ↑ GA Pugachenkova: Transoxania and Khurasan, S. 524f

- ^ Karl Jettmar : Siberia and the steppes of Asia . In: L. Fasani (ed.): The illustrated world history of archeology . Munich 1979, pp. 572-585, here p. 577

- ↑ K. Baypakov, Sh. Pidaev, A. Khakimov: The Artistic Culture of Central Asia and Azerbaijan, p. 15

- ^ Robert Hillenbrand: Islamic Architecture. Form, function and meaning. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 1995, pp. 280, 290

- ↑ James Davidson Deemer: Islamic art resources in Central Asia and Eastern and Central Europe. Proceedings of the Fifth International Seminar for Islamic Art and Architecture, Al al-Bayt University, Mafraq, 19. – 24. April 1996, p. 68

- ↑ Khoja. In: Kamoludin Abdullaev, Shahram Akbarzadeh: Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan . Scarecrow Press, Lanham 2010, p. 201