Qubodijon

|

Qubodijon убодиён |

||

| Basic data | ||

|---|---|---|

| State : |

|

|

| Province : | Chatlon | |

| Coordinates : | 37 ° 24 ' N , 68 ° 11' E | |

| Height : | 402 m | |

| Postal code : | 735140 | |

|

|

||

Qabodiyon ( Tajik Қубодиён ; Russian Кубадиян , Kubadijan ; and Cuba Dijon; English transcriptions Qabodiyon, Kabodion; formerly Mikojanobod / Микоянобод , Russian Mikojanobadski / Микоянобадский ) is a village and capital of the district of the same name ( nohija ) in the province of Khatlon in southwestern Tajikistan . Qubodijon is known as the birthplace of the 11th century Persian poet Nāsir-i Chusrau . The Iron Age , Graeco-Bactrian and medieval fortress town Kala-i Mir (Калаи-Мир, settled from the 7th / 6th century BC to the beginning of the 20th century) in the center has been almost completely destroyed. Their settlement mound was archaeologically examined in the 1950s, as was the fortified settlement Kej-Kobad-Schach (Кей-Кобад Шах, settled from the 3rd / 2nd century BC to the 4th / 5th century AD. ), which was outside the village and is now leveled under a cotton field.

location

Qubodijon is located on the A384 expressway, which leads south from the state capital Dushanbe via Obikiik. Not far from Qurghonteppa the road reaches the valley of the Wachsch and follows it on its west side downstream to the level of the urban settlement Kolkhozobod on the east side of the river. Shortly thereafter, the road changes over an approximately 20-kilometer-wide, almost vegetation-free hilly area into the parallel valley of the Kofarnihon to Qubodijon to the west . The distance from Dushanbe is around 165 kilometers, from Qurghonteppa 81 kilometers and to the next urban settlement Shahritus in the south it is 17 kilometers. The Kofarnihon flows into the Amudarja about 50 kilometers south of Qubodijon , which forms the border with Afghanistan over a long distance . The (little) long-distance traffic on the A384 to the south continues to the Uzbek border crossing and to the nearest city of Termiz .

Until around 1930, the south-west of the country was only accessible by dirt roads. The large-scale cultivation of imported cotton in the 1930s in the valley plains on the lower reaches of the Wachsch and Kofarnihon made it necessary to develop the infrastructure. In 1932 the first narrow-gauge railway line from the loading point Panzi Pojon on Amudarja to Qurghonteppa went into operation. In that year, the first road from Dushanbe to Qurghonteppa was also completed. Today a railway line that was constructed between 1966 and 1980 runs roughly parallel to the A384, from the junction in Termiz via Qubodijon and Qurghonteppa northwards to Jowon (264 kilometers). In 1999 the connection from Qurghonteppa to the east via Danghara to Kulob was added (132 kilometers).

The place is located on the left (eastern) side of the Kofarnihon in a wide valley plain, which is bounded in the east by a north-south running range of hills, the highest point of which reaches 1632 meters nearby. The highest temperatures in the country are measured in the plains in the southwest: the average maximum temperature in Shahritus in July is 37.9 ° C, the average minimum temperature in January - 1.8 ° C. With an annual precipitation of 235 millimeters in Schahritus, which mainly falls in the winter months, agriculture is not possible without artificial irrigation. According to other information, the average rainfall in the Kubodjon district is only 157 millimeters, the average temperature in January is 1–3 ° C and in July 32–33 ° C. There is a subtropical steppe climate.

District

The area has been mentioned in the sources as Qubodijon since the 7th century. When the district ( nohija ) Kubodjon (Ноҳияи Қабодиён) was founded in 1939, it belonged to the Stalinabad Oblast of the then Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic . Between 1930 and 1970 the district and place were called Mikojanobod (Russian: Mikojanabadski) in honor of the Soviet politician of Armenian origin Anastas Mikojan (1895–1978). Between 1944 and 1947 and again from 1977 to 1992 there was a Kurgan-Tjube (Qurghonteppa) oblast, formed from parts of the Kuljab (Kulob) and Stalinabad oblasts, to which the Mikojanabadski district belonged. After the country gained independence in 1991, the administrative units were restructured. At the end of 1992 the Kurgan-Tjube and Kuljab oblasts were united to form the province ( wilojat ) Chatlon. Kubodjon is one of the 24 districts of Khatlon and consists of six sub- districts ( jamoat ).

The Kubodjon district borders in the east on the Jilikul district, in the south on the Afghan province of Kunduz , in the west on the Shahritus district and in the north on the Rudaki district, which belongs to the Nohijahoi tobei dschumhurij region ("districts subordinate to the republic"). The area of the district is 1834.4 square kilometers (according to other information 1878 square kilometers), the population was 145,800 in 2009. The entire area in southwest Tajikistan is known as the Qubodijon oasis. In addition to Qubodijon, these include the districts of Schahritus and Nosiri Chusraw (formerly Beschkent) along the Uzbek border.

Qubodijon is one of the four larger cotton-growing areas in Tajikistan. Cotton is the main agricultural export product and accounts for 20 percent of the country's export revenue, even if production has declined sharply since 2005 and the cultivation of fruit and vegetables is increasing. The decline has been recorded despite the fact that regional administrations are forcing farmers to plant cotton on 70 percent of their arable land and threatening to expropriate the land if they violate it. Cotton is the main source of income for 75 percent of the poor population. The district's utilized agricultural area was 16,001 hectares in 2010, 14 percent less than in 2000 (18,589 hectares). In the cotton fields belonging to large state or private companies, only women work on low wages. Most of the cotton-producing companies in Qubodijon and the neighboring districts are managed by the state investment company TASS. TASS grants land, organizes tax exemptions, regulates debt freezes, and distributes state gifts. Private companies are part of the same patronage network that is under the direct leadership of President Rahmon .

In addition to cotton on 5862 hectares, wheat (80 percent of all grains), corn and rice on 5257 hectares and vegetables on 1433 hectares were grown in 2010, according to the agriculture department of the district administration. According to the same information, 2 tons of cotton per hectare were harvested this year. This amount corresponds to the yield of other developing countries, while for Tajikistan an average of 1.5 to 1.8 tons per hectare is given. In 2004, Qubodijon achieved a yield of 2.3 tons of cotton per hectare under particularly favorable climatic conditions. The area under vegetable cultivation increased in the decade from 2000 to 2010 by 1.48 times, the yield increased by almost three times.

The fields are irrigated through small channels ( arik ) from the Kofarnihon. The irrigation systems in Tajikistan have a long tradition that goes back to the first half of the 1st millennium BC. Goes back to BC. During the Soviet era, the irrigation systems were owned by the state and administered centrally from Moscow. During the civil war in the 1990s, the irrigation systems fell into disrepair and some of them were unusable. Although they have been repaired since then, there is still a lack of adequate maintenance, so that the high evaporation rates lead to increasing salinity of the soil in summer. There are not enough drainage ditches that could counteract the salinisation of the cotton fields. As a result, thousands of hectares in the Qubodijon and Schahritus districts, among others, became unusable for cultivation.

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of livestock in the district increased sharply. The number of sheep (mainly Karakul sheep ) doubled from 35,131 (2000) to 79,320 (2010) and the number of cattle rose from 20,572 to 38,435. A cow produced 670 liters of milk (2000) compared to 1038 liters (2010).

In the 1950s, many Tajiks were forcibly relocated to work in the cotton fields in the south-western plains from the Rasht Valley in the central part of the Rasht Valley, with the main town of Gharm . The newcomers called Gharmi (Ғармӣ) form a separate ethnic group alongside the long-established Tajiks, Uzbeks and a small minority of Arabs. During the Tajik civil war, which lasted from 1992 to 1997, the Gharmis initially occupied most of the public offices in the Qubodijon district. Ethnic tensions arose, especially between Gharmis and Uzbeks, and intense fighting between the groups in late 1992. Uzbeks and long-established Tajiks set fire to their opponents' houses and drove out the Gharmis, most of whom fled to Dushanbe. The following March, many of the displaced were brought back to Qubodijon by rail, where they were prevented by Uzbeks and Arabs from entering the place or from returning to their kolkhozes . According to UNHCR estimates, 5,000 houses were destroyed in 1992/93 in the districts of Shahritus and Qubodijon.

Townscape

The place name Qubodijon is derived from the old city Kej-Kobad-Schach (Kei-Kobad-Schah, "King Kai Kobad", also Kabot Schahnor, short Kaikobad or Kuad). Their name refers to the mythical king Kai Kobad in Iranian mythology , who belonged to the Kayanid dynasty . He appears in the epic Shāhnāme by the Persian poet Firdausi and is said to have lived here. Another place name with reference to this king is Tacht-i Kobad ("Throne of Kobad") around 40 kilometers south of Amu Darya. No other region is so closely associated with the Kayanids in the tradition.

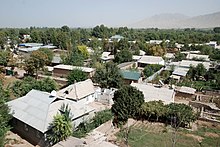

A few shops are lined up along the thoroughfare that runs through the compact town from northeast to southwest. There are restaurants and a market in the center. A network of parallel side streets opens up the agricultural farms, which are surrounded by large gardens with trees.

100 meters east of the road there is an open space in the center with the remains of the Kala-i Mir fortress. In this area, on the opposite side of the street, an alley leads to a private house, of which residents explain that this was the place of birth of Nāsir-i Chusraus. An old tree is shown, near which the poet is said to have been born in 1004. According to Soviet archaeologists, a building with thick walls belonged to a palace from the time of Chusrau. The small remains of a mausoleum (Persian gumbaz , domed structure) have been preserved here.

Excavations

On the lower reaches of the Kofarnihon, around Qubodijon and Shahritus, over 100 historical and cultural sites are listed, of which mostly only small remnants have been preserved. The first archaeological explorations in this area took place between 1946 and 1948. Bronze Age finds in the Qubodijon region come from the Tulchar cemetery, excavated by AM Mandelshtam from 1965 to 1969, in the Beskent valley west of the Kofarnihon (a few kilometers north of Tschilu-chor chaschma ). The pottery found refer to nomadic inhabitants living there who lived in the 1st century BC. Chr. A sedentary culture gave way. In the valley of the Kofarnihon were from the first half of the 1st millennium BC. Chr. Canals built to irrigate the fields around the Iron Age settlements. The settlement of Kala-i Mir was excavated by Soviet archaeologists under the direction of MM Diakonow in 1950–51. Remnants came from around the 6th century BC. When the area belonged to Bactria , it appeared until the 4th century AD, i.e. shortly before, during and after the Kushana rule. In addition to Kala-i Mir, the Achaemenid settlements of Tacht-i Sangin and Tacht-i Kobad in the south of the Kubodijan district on the banks of the Amu Darya were of particular archaeological interest because the Oxus treasure , which was discovered in the 1870s, is believed to have been found in their vicinity .

According to the pottery finds by Kala-i Mir and Kej-Kobad-Schach, Diakonow (1954) identified five phases:

- Kubodiyan I: 6th to 4th century BC BC, Kala-i Mir, “ancient Bactrian culture”, pre-Amenid foundation

- Kubodijan II: 3rd to 1st century BC BC, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom , Kei-Kobad-Shah

- Kubodijan III: 1st century BC BC to 1st century AD, gray pottery

- Kubodijan IV: 2nd century AD, time of King Kanishka , red pottery

- Kubodijan V: 3rd to 4th century AD, late Kushana empire, pottery and coin finds

AM Mandelshtam (1959, 1966) established an independent chronology for Tulchar, which is based on coin finds, because there was no temporal comparison between the ceramic finds of the two excavation sites.

Kej-Kobad-Schach was a fortified Bactrian settlement on the right bank of the Kofarnihon, 1.5 kilometers away from today's place Qubodijon. Century BC Was founded and until the 4th / 5th. Century AD existed. It was discovered by Djakonov in 1949 and excavated in the early 1950s. As the large amount of pottery and the discovery of a gold coin show, the residents were relatively wealthy. The enclosing walls from the 4th to 2nd centuries BC Were regularly repaired, they included a rectangle of 383 × 285 meters. Pillar bases and Corinthian capitals indicate a Hellenistic influence, as do the many Greek letters that were engraved on the bricks of the ramparts. The exactly straight walls each had a gate in the middle. The connecting routes between the gates divided the city into four rectangular districts. Kej-Kobad-Schach belonged to a number of north Bactrian fortified cities, of which Termiz on Amu Darya was the largest and strategically and economically most important. A smaller fortified settlement of this time was Kuchna Kala on the left bank of the Wachsch with a surrounding wall of 250 × 125 meters. The excavation site was leveled before 1970 and disappeared under cotton fields.

From the oldest layer Kubodijan I of Kala-i Mir (from the 7th century BC) ceramics came to light, those from the same period of Gyaur Kala (today Merw in Turkmenistan), Afrasiab (near Samarkand in Uzbekistan) and Resembles Balkh (Northern Afghanistan). Even more than the French excavations carried out in Balch in the 1950s, the investigations of Qubodijon provided information about the Iron Age chronology in eastern Central Asia. The iron and bronze devices found can be compared with those of Jaz Tepe (34 kilometers north-northwest of Baýramaly in Turkmenistan). The finds there are three phases between 900 BC. BC and about 350 BC Assigned. The settlements that were also inhabited in the Hellenistic period (after Alexander's conquest around 328 BC) also include south of the Amudarja Yemschi Tepe (four kilometers northeast of Scheberghan in northern Afghanistan), Tepe Nimlik (36 kilometers west of Balkh in northern Afghanistan) and Delberjin ( 40 kilometers northeast of Balkh).

Diakonow compares the pottery of Qubodijon IV from Kala-i Mir and Kej-Kobad-Schach with the Kushana-period finds of phases I and II of Begam (Afghanistan). Between Qubodijon IV and V he found a 30 to 40 centimeter high, empty layer during excavation IA in 1950, which consisted of an 8 × 10 meter test excavation in Kej Kobad chess. In further excavations in 1953 it turned out that there were no traces of settlement from the 1st century BC at other places in the area either. Existed. In contrast, other places in Bactria experienced a heyday under the rule of the Kushanas. No evidence of a military attack on Qubodijon was found. The residents had evidently moved away during this time, the reasons for this being unknown.

Significant social and economic changes took place in southern Central Asia in the 5th century. Some places survived the transition from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages in a modified form. In the 6th century, the medium-sized fortress town of Kafirkala (in today's Kolchosabod settlement) developed into the political center on the lower Wachsch. Kala-i Mir was also inhabited in Islamic times and for a long time served as the residence of local tribal leaders ( Begs ). The last beginning was expelled by the Soviet troops in 1921 when they conquered Central Asia. He presumably left for Afghanistan.

The visible settlement hill ( Tepe ) of Kala-i Mir rises an average of about ten meters from the plain. The north-south oriented, rectangular settlement area was four hectares. Only on the west side small remains of mud brick wall remains of its mighty fortifications . What was left after the excavations in the 1950s was eroded by high temperature fluctuations and wind.

literature

- Kamoludin Abdullaev, Shahram Akbarzadeh: Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Scarecrow Press, Lanham 2010

Individual evidence

- ^ MV Hambly: Road vs. Rail. A Note on Transport Development in Tadzhikistan. In: Soviet Studies, Vol. 19, No. January 3 , 1968, pp. 421-425, here p. 421

- ^ Railways . In: Abdullaev, Akbarzadeh: Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan, p. 297

- ↑ Sharitus, Tajikistan. weatherbase.com (climate table for Schahritus)

- ↑ Qubodiyon Nohiya . In: Abdullaev, Akbarzadeh: Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan, p. 291

- ↑ Khatlon . In: Abdullaev, Akbarzadeh: Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan, p. 199

- ↑ Qubodiyon Nohiya . In: Abdullaev, Akbarzadeh: Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan, p. 290

- ^ The Economics of Land Degradation for the Agriculture Sector in Tajikistan. A scoping study. UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Initiative in Tajikistan, Dushanbe 2012, p. 71

- ↑ Hafiz Boboyorov: Collective Identities and patronage networks in Southern Tajikistan. (ZEF Development Studies) Lit, Münster 2011, p. 176

- ^ Priorities for Sustainable Growth: A Strategy for Agriculture Sector Development in Tajikistan. World Bank-SECO Report, 2010, p. Viii

- ^ The Economics of Land Degradation for the Agriculture Sector in Tajikistan. A Scoping Study, pp. 20f

- ^ Sophie Roche: Domesticating Youth: Youth Bulges and their Socio-political Implications in Tajikistan. Berghahn, New York / Oxford 2014, p. 44

- ↑ Hafiz Boboyonorov: Masters and networks of knowledge production and transfer in the cotton sector of Southern Tajikistan. ZEF Working Paper Series No. 97, University of Bonn, 2012, pp. 11, 13

- ↑ Frank Bliss: Participation in rural development and water supply in Tajikistan . ( Memento of the original from January 20, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ( Participation in regional development and development cooperation in Central Asia using the example of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan . Project Working Paper No. 5) University of Duisburg Essen 2013, p. 54

- ^ The Economics of Land Degradation for the Agriculture Sector in Tajikistan. A Scoping Study, pp. 71f

- ↑ Rachel Denber: Human Rights in Tajikistan in the Wake of Civil War . Human Rights Watch, New York et al. a., December 1993, pp. 31, 41f

- ↑ Hamid Wahed Alikuzai: Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes: Volume 14 . Trafford Publishing, Bloomington 2013, p. 113

- ^ Robert Middleton, Huw Thomas: Tajikistan and the High Pamirs . Odyssey Books & Guides, Hong Kong 2012, pp. 213, 216

- ↑ Alijon Abdullayev: Groundwater and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Tajikistan (Kabadian Valley). In: Proceedings of the Regional Workshop "Ground Water and Soil Salinity Related Damage to the Monuments and Sites in Central Asia." Samarkand / Bukhara, Uzbekistan, 14.-18. June 2000, p. 41

- ^ Grégoire Frumkin: Archeology in Soviet Central Asia. ( Handbook of Oriental Studies, 7th section: Art and Archeology , 3rd volume: Innerasien, 1st section) EJ Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1970, p. 69

- ↑ Kalai-Mir. In: The Great Soviet Encyclopedia . 3rd edition, 1970-1979

- ↑ Vadim M. Masson: The land of a thousand cities. Bactria - Khorezmia - Margiane - Parthia - Sogdia. Excavations in the southern Soviet Union. Udo Pfriemer, Wiesbaden / Berlin 1987, p. 85

- ^ Edgar Knobloch: Treasures of the Great Silk Road. The History Press, Gloucestershire 2013, p. 61

- ↑ Aleksandr Belenickij: Central Asia. (Heyne. The great cultures of the world. Archaeologia Mundi) Nagel, Geneva 1968, pp. 84f

- ↑ Lazar Israelowitsch Albaum, Burchard Brentjes : Guardian of Gold. On the history and culture of Central Asian peoples before Islam . VEB Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1972, p. 81

- ^ Grégoire Frumkin: Archeology in Soviet Central Asia , p. 67

- ^ Karl Jettmar (ed.): History of Central Asia . ( Handbook of Oriental Studies. First section: The Near and Middle East . Volume 5: Altaic Studies, Section 5.) Brill, Leiden 1966, p. 47

- ↑ André Maricq: The Date of Kaniška. Two Contributions in Favor of AD 78 . In: Arthur Llewellyn Basham (ed.): Papers on the Date of Kaniṣka: Submitted to the Conference on the Date of Kaniṣka, London, April 20-22, 1960 . EJ Brill, Leiden 1969, pp. 191f

- ^ BA Litvinskij, VS Solovjev: Kafyrkala. Early medieval town in the Vachš Valley, southern Tadžikistan. (Materials for general and comparative archeology, volume 28) CH Beck, Munich 1985, p. 89

- ^ Robert Middleton, Huw Thomas: Tajikistan and the High Pamirs . Odyssey Books & Guides, Hong Kong 2012, p. 216