Urban morphology

Urban morphology is a research area in urban planning , urban planning and urban geography .

Urban morphology deals with the forms of settlement and town as well as with the physical formation processes within the settlement bodies. The object is therefore the structure of the development, the formation of parcels as the basis for buildings, the building typology and the networks of development.

A special focus is on the historical analysis of the development and transformation of urban structures. Questions such as “Which types of construction have a long service life and why?” Or “How elastic is the existing structure to adapt to new needs?” And “Are the features of the existing structure also a benchmark for new buildings?” Are just a few aspects which urban morphologists deal with.

The term “morphology” (the theory of shapes) taken up is a genetic term that goes back to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , who introduced it for the study of the genesis of forms. In language, morphology means the theory of forms, which, based on the word, includes the analysis of the inflected forms and the parts of speech and can also include word formation. In the field of physical geography , geomorphology deals with shapes and form-forming processes on the surface of the earth and celestial bodies.

Further explanation of the term urban morphology

The morphological approach to settlements and cities is an old field of activity in urban history research and geography. In 1997 a scientific dialogue center was developed with the journal Urban Morphology . It is published by the International Seminar on Urban Form (ISUF) at the University of Washington, Seattle. In addition to the magazine, which appears twice a year, annual conferences in different countries are meeting points for scientists from many countries who present studies and discuss methods. The scientific field of urban morphology is little developed in Germany. Strong research groups can be found in England, USA, France and Italy.

Urban morphology is understood to be the form principles according to which city floor plans are built and according to which they were created. Important aspects are the conditions of origin and the spatial characteristics. The shape of the city is determined by the political, social, economic and technical conditions of the time. Often, older structures are retained and re-shaped in the process. One possible approach to urban planning is to look at the city through time.

The shapes can be regular or irregular: regular shapes tend to indicate planned, irregular shapes that have arisen in small steps or even unplanned. An irregular urban morphology is often found in a moving topography, because regular road networks would often lead to uneven gradients there.

Old city plans often contain information from the time the city was built and from times of significant changes. These can be recognized by changes in the geometry of the urban layout, changes in the routing of streets and house fronts, and in the alignment and size of parcels . The material structure of city plans therefore contains valuable city-historical information which, in addition to the literary and pictorial traditions, is the basis of a spatial, technical and social city history .

The current discussion is strongly influenced by the English school of thought, which focuses on a rather small-scale consideration of city quarters or small towns. Three theoretical approaches dominate this discussion:

- Figure and ground (Figure and Ground)

- Structure theory or theory of spatial connection (linkage theory)

- Theory of the place (Place theory)

The figure-ground theory examines the relationship between the built-up areas (figure) and the areas left free by buildings (ground). The structural theory is derived from the lines or connections that link the individual structural elements with one another (streets, paths, open space), and from the connections that the predominant forms enter into with one another. This also includes “remaining spaces” as intermediaries between non-connectable forms. The term "Schwarzplan" is also used for this in urban planning. Recently, a team of architects, u. a. Inspired by this article, an "Atlas of Urbener Structures" with the title "The DNA of the City" was published for numerous German cities using the method of Figure Ground Plans.

The theory of the place relates to a. on the “conscious handling of specific places”, their “cultural charges” and their development potential (E. Raith). In this context, a school of thought developed in human geography in the course of the 1990s that regards the cultural landscape as "text". It is assumed here that a meaning is inscribed in the built environment that can be read out in a scientific analysis: In this understanding, a city can also be read as text: “City as text”.

A more recent research field based on urban morphology is urban space history , which examines the development of urban space in the respective socio-economic and cultural context and considers urban space as the main source.

Concept and phenomenon of the city

Cities have existed for over 5000 years ( Mesopotamia , Indus region Mohenjo-Daro ). In the Mediterranean region, urban development first developed from east to west ( Mesopotamia , Jordan Valley (Jericho), Egypt, today's Turkish region, Greece, Italy, Spain) and then from mainland Europe to the north (France, Germany, British Isles, Scandinavia). From around 1150 a planned expansion of the city system began - mainly supported by locators (city founders) and trading companies ( Hanseatic League ) as well as by the Teutonic Knights Order eastwards along the Baltic Sea and into the areas of today's Eastern Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria and Hungary.

The first cities were regularly created "planned cities". The Roman cities also followed a fixed plan. In the Middle Ages, a second type of city developed: the “irregular city”, the floor plan of which you can often clearly see the history of development from an older core to several rings or extensions. The irregularity is due to the topography (e.g. mountain towns in Italy), or from the gradual growth around castles , rivers and valleys, but also from the often round wall rings and the limitation of the number of gates to the necessary minimum. This made bends and forks of inner roads necessary, which had to be fed through the gates onto the main roads into the surrounding area.

From the beginning, cities are associated with civilizational features such as security ( city fortifications ), means of payment (regional, local currency), legal system ( city law ) and obligations for residents and city citizens: defense, taxes, services for the general public.

From the Middle Ages onwards, a spatial division of labor had developed between town and country : the surrounding country supplied the town with food , building materials and fuel , and in return the town supplied the surrounding area with specialized goods and services.

Within the cities, too, specializations in the use of space developed based on the division of labor: administration and trade occupied the city center, craftsmen concentrated in guild streets, disruptive trades were located on the edge or outside the walls. Nevertheless, until the beginning of industrialization, there was a clear boundary between town and country through the town wall , the separating effect of which was mostly retained for a long time after the removal of customs duties and the demolition of the walls. Since the development of mass transport, the city no longer ends at its political borders. Depending on the regional settlement structure, the city's social and economic zone of influence extends far into the surrounding area, including beyond neighboring cities. It is therefore an important task of cities to provide a suitable spatial form of organization for the (local and regional) division of labor and its changes.

Cities are complex phenomena. No theory or combination of analytical methods, however complex, can fully map the diversity of what happens in a larger city. Cities can be described through their history , features of their present , the usage and real structure, through statistical data, accidents and crimes , impressions, the representation of experiences and fates or through the change of certain parts of the city - as Nik Cohn did about change of Broadway using the example of people. In all cases, however, it is a matter of depicting sections of various facets of reality. Even if an army of “ town clerks ” wanted to record all events, the conspicuous would receive an impermissible preponderance over the inconspicuous, the public events would get a dominance over the private ones. It is often the small everyday behaviors and values that influence the development of settlement systems en masse, such as the need for spacious apartments, for living in the country, for individual means of transport . Trends can be influenced locally, but they can hardly be created or brought to an end. For this, value creation and orientation happen far too locally, sometimes in a global process. Public control and planning can therefore, at best, influence certain characteristics of dominant movements.

This was not significantly different in earlier times in the city's history. An example of this is that in the Middle Ages cities were largely determined from outside in their development - for example through the use of almost identical city plans when founding cities in the East Elbe or through the commitment of well-known builders from other places to build churches , town halls and city extensions. Even in the course of the great urban expansions of the last century, attempts were always made to solve local problems to use the knowledge of the respective time - and not just the knowledge on site - at the service of the task.

In this respect, cities are and were on the one hand always focal points of a civilization and at the same time places of its development and further development. This dual character of being both a motor and being moved by external forces leads to ever new demands on the spatial organization of the uses in the city and its surrounding area.

The development of city plans

Urban morphological structure

The persistence and the great inertia of the existing urban structures stand against the dynamics of change . The existing structures oppose the change with a resistance that corresponds approximately to their market value , their political and cultural value or the cost of their removal. Very large technical, legal and financial resources - apart from the time required for preparation and implementation - are required to fundamentally change intact structures. This is why the rates of change - except in pronounced boom times and in authoritarian situations - are generally small in relation to the structural mass.

A key feature of cities is their layout. It is something like the genetic code of the city and shows the “pattern” according to which the elementary building blocks of the city - the buildings and parcels - are arranged. This pattern already defines significant properties: regular or irregular arrangements, shape, scale and hierarchy of the street networks , the density of the building arrangement, the uniform or non-uniform occurrence of repetitive building forms , the distribution and shape of larger squares and open spaces.

The city is not directly comparable to a natural organism , but there are similarities that make it easier to understand. Living organisms renew z. B. permanently part of their cells, but never all at the same time and rarely concentrated in one place; special developmental events often leave traces in the structure of organisms. Matter has developed solidifications, detours, scars or substitute developments to ward off a threatening event. Similar traces have often been preserved in city plans over centuries.

We can also see a permanent “cellular” renewal process in cities. Complex biological and human systems have similarities in the inertia of the system's behavior against sudden changes. There is a certain behavioral autonomy of elementary parts, which relieves the overall system of central rules.

It is therefore of general interest to know more about whether there is such a thing as a built-in logic of development, change and renewal in the order of the morphological structure of city plans. Changes arise from individual and social interests and not from the structure itself. However, the peculiarity of the structure has a certain influence on this.

Grown and planned cities

To simplify matters, a distinction can be made between two morphological structures: those that are based on plans (planned cities ) and those that do not follow any geometric design. While the internal organization and formal order are the focus of the basic geometric shapes, the non- geometric morphological structures react more strongly to the situation. Right from the start, they are a synthesis between internal organizational needs, climate and topography . On the other hand, they have weaknesses in accommodating the increasing spatial and interconnection demands on traffic in the given, mostly confusing and complicated road network structure in later phases of expansion. In contrast, regular networks have no problems with expansion, except for topographical obstacles.

Structure-forming forces

An abstraction of specific cultural, topographical and climatic influencing variables reveals general variables that are behind the design of urban structures:

- The first and most important structure- forming force, which acts almost everywhere regardless of the individual case, is the minimization of the effort required . This includes the physical and psychological as well as the time required to overcome space. Shortening diagonals arise from such collective needs. However, the shortest route is not always the fastest; therefore, longer distances than avoiding obstacles can be shorter or more convenient in terms of time. If the topography is moving, longer routes with pleasant inclines save energy. Saving time and energy conserves resources that can be used for other purposes than overcoming space. Direct consequence thereof, the concentration of uses in places and lines with high accessibility from the center and the surrounding areas or the increasing compaction of the building in central areas of a city. High land values in central city locations have to do with accessibility and this in turn has to do with the minimization of effort and effort. The same applies to the formation of usage agglomerations around locations with easy accessibility, such as B. Commercial centers at motorway junctions on the periphery . This structure-forming force works independently of the means of spatial movement , but generates other spatial patterns that correspond to the respective means. Since the means of locomotion overlap and mix, it depends on the dominance and the persistence of the existing structures which means of transport they are ultimately based on. Inevitably, there are compromises that do justice to the various means. But it can also come back to earlier organizational patterns, if z. B. city centers are redesigned again more related to pedestrians .

- A second structure-forming force is the demands placed on space by important production forces. Since the city lives as an artificial structure from the division of labor production and distribution, the functional conditions always had and still have an influence on the location structure and the shape of the city.

- The need for variety and distinction can be named as the third force . This also includes questions of orientation and the symbolic expression of social differentiation . This results in variations of open spaces, streets, buildings and morphological structures.

- The fourth force is the need for order . Order has an important function in the individual and collective organization of external living conditions. It relieves the perception apparatus, facilitates search processes, and provides a framework for diverging spatial requirements. Since maintaining order also takes time and effort, the order of the structure does not always have the same meaning. When examining city plans over long periods of time , it is noticeable that phases of strong intervention and control are often followed by periods of lesser regulation.

- As a fifth force, the social bond of the person acts on the structure. This leads to certain spatial organizational patterns such as city districts and quarters . But this also gives rise to the significance of the city's history for evaluating the structure: people cannot only live in the present. Past and future are dimensions of life that tie the individual and the existing society into a period of human history, the local expression of which opens up opportunities for identification and bonding.

- The sixth force is the inertia of the physical structure and the spatial form of its organization. It is particularly noticeable in a long-term comparison of urban structures that the development principles laid down in the early phases of development hardly change. Existing structures oppose physical and legal-economic resistance to change. The urban planning therefore and urban policy must expend considerable political, financial, human and temporal power, if it wants to change structures against their inner logic from the outside. This is mostly only possible in a few areas.

- There can also be other forces such. B. economic aspects, competition with other cities, need for self-fulfillment , for loyalty, technical functional requirements , local and national planning and land law are mentioned.

Because the physical structure is long-lived and sluggish, in countries with a long urban culture it forms a stable framework for the life of people in the cities. The living generation must therefore largely come to terms with what the previous generations have left behind. In larger cities, adaptation to new needs is only possible in small steps and only to a limited extent. The structural past is thus an integral part of the present. It is also a measure of the control of the new.

The cultural significance of the historical cores and the extraordinary sensitivity of these areas to major interventions are outstanding and effective in the long term. Over time, an unstable and sensitive balance develops between structures and content, but also between function and shape.

In terms of planning, it is therefore essential to secure poles of stability in addition to areas of change , because they have to do with recognizability, with the image of the city and with its connection between past and future and therefore with the possibilities of identification of its residents . Finally, in the " time lapse " it can be seen that within the apparently firmly established framework of networks and building structures, a permanent, small-scale change takes place, the stable-looking structure is therefore in a permanent movement of micro-adaptation to new requirements and thus creates a renewal of system elements, without which the overall structure would not be able to survive.

At certain intervals, however, the structure is supplemented by major additions and innovations . This is partly due to a need of the generations, at least at some points in the city, to give the zeitgeist and their own urban concepts structural and spatial expression. Together with the persistence of the urban structure, which has a calming and disciplining influence, the necessary experiments and samples of every generation can find space and form in the continuity of the basic organizational structure, as long as the logic built into the structures is observed. In the history of the structure lies the logic of mostly centuries of experience on site, the careless task of which can have significant negative consequences for the overall system.

Organization of the city structure

Urban morphological structures consist of networks and structural elements. Elements are individual buildings, parcels and building blocks. The existing networks have to react to the expansion of cities, to changes in the capacity requirements for the cross-sections and to new transport systems . Since the existing network structure of larger room units can hardly be changed, often only additions, completions or corrections are possible. On the one hand, time-related views prevail - as can be seen on every city map. On the other hand, the time and convenience of the spatial connection have an impact on the network development as a permanent, time-independent component.

The study of the long-term development of larger urban networks therefore provides structural information about the logic of networks that goes beyond the current tasks of a time. This shows that networks develop hierarchical structures with increasing size of a territory . A system of main and secondary lines is created, which have different meanings for the supply of areas. This applies to almost all infrastructure networks ( electricity , water , sewage , roads, railways).

Key elements of such hierarchies are mass transportation lines such as main roads , radials, rings, and tangents. It turns out that, with the exception of cities with spatial restrictions in expansion, the ring-radial development asserts itself as a basic development pattern because it connects the area to be populated and the further periphery to the core in the most favorable way.

Macro Development Factors

Radial development

The radials are the real lifelines of the city. They connect the core with the edge and both areas with the surrounding area. As far as exchange processes are carried out via roads, the radials leading in from the outside are structurally preferred locations. Due to this importance, radials are broadly developed roads, they have good, often the best, public transport service. Due to their linear shape, they offer numerous locations and, with increasing distance from the core, also a different level of soil values. Structurally, they resemble the linear center or the ribbon city, which bring together very different uses on one axis (architecture) . In terms of time, it is easier to look for and find a use on a linear band than in the network of indistinct city districts.

The different types of settlement and building densities affect the radial lines; They also cut the boundaries of built-up areas (parts of the “urban fringe”) and still isolated suburbs and fragmented settlements. In the city center they cut through areas with a high vertical and horizontal density of use, on the periphery they touch loosely built suburbs and villages.

This heterogeneity, which is often perceived as annoying aesthetically, is also an important development factor:

Underused spaces are juxtaposed with organizational areas and open spaces. They are reserves for new uses that give the radial new development impulses. The radials are therefore particularly important basic elements of the settlement structure.

Ring development

If the populated areas have exceeded a certain extent, connection deficits between the peripheral parts arise. In orthogonal networks the diagonals develop , in radial concentric networks the rings. The rings connect the radials with each other and relieve the city center of traffic. The formation of a well-managed system of rings is an indicator of the degree of maturity of a spatial structure.

Ring Radial Development

All observations over many centuries of urban development show that the settlement initially develops along existing access routes to the outside. After that, the available areas between the radials fill up until the demand for a period is sufficiently saturated. Over time, the closest areas are populated both on the radials and in the spaces in between, until the development finally reaches physical or legal limits. In the end, only those areas that do not come onto the property market, that are subject to legal barriers or technical restrictions (poor building site, city walls, city limits) set limits to the expansion. These intermediate zones appear indistinctly in orthogonal access structures, since the basic geometric principle does not result in any residual areas. If the geometry is given up in the periphery, similar patterns develop there.

Urban fringe

Since development is initially concentrated on the major axes, areas that are free or underutilized remain on the periphery of the previous settlement or in poorly developed spaces. These areas have the function of a hidden development reserve. After overcoming the previous limits, they acquire a special strategic development significance in connection with the newly added areas outside the barriers.

The outskirts of the city or “fringe belts” seem to have a corrective and development function at the same time. Their peculiarity is that they, as the periphery, have long been out of consideration and are little involved in the design and network concepts of the urban fabric. Agricultural uses, allotment gardens and low-intensity uses (e.g. storage functions) are often found in an often coincidental “mixture” on the interior spaces that have remained free between the radials. When the uses on the radials have penetrated far enough to the outside, these settlement-structural "rear areas" acquire a new meaning because of their increased relative proximity to the core. Although they are located off the main access roads, they are now closer to the core than the periphery. New residential or commercial areas are now being built here . But they are also important locations for infrastructure facilities that have become necessary as a result of the city's expansion.

The infrastructure locations are worth a closer look. These are locations that lie between the inner, older growth ring and the newly developing outer district or suburb rings. Infrastructures at these locations are therefore in a favorable intermediate location in the catchment area of inner and outer urban areas. Even if they are often not located directly on the radials and are therefore somewhat more difficult to reach, on the other hand they can be found in large and inexpensive areas in relatively quiet locations. If you then examine the locations of larger infrastructure facilities such as railways , schools, universities , parks, cemeteries and sports facilities, they are often located in such intermediate areas. They do not arise there on the basis of models of an optimal location distribution, but in the absence of other alternatives in locations that are absolutely sensible in terms of urban structure.

Structurally particularly interesting are examples in which settlements had already progressed further out and it was only later possible to fill in such spaces. Prominent examples of this are the Ringstrasse in Cologne and Vienna .

Stability and change of location systems

More complex spatial networks in densely populated urban areas are very stable. Due to the high stability of the networks, changes can only be made in small steps over a long period of time or only in "soft spots". Soft spots are rear areas, sparsely populated zones, zones with low land values and zones with disordered and low-value uses. New network capacities, new means of transport and changes in the urban network or building structure therefore find their limits in the monetary, political and temporal costs of their implementation. A long-term view shows that major interventions are usually only carried out in the event of bottlenecks that threaten the overall system, after disasters and during particular periods of upheaval.

The high inertia towards changes also applies to the locations of high local or regional accessibility preferred by the network geometries. Radially concentric networks, preferring a geometrically determined central area, determine the locations for the city center and for district centers. In orthogonal systems, shifting the core areas is much easier. However, this situation changes with the introduction of new network elements (such as tangents, rings) if they create new accessibility and new node areas through better local or regional links. This can partially or fundamentally influence the existing location system. As a result, uses are located at nodes that are now more accessible and often only target spatial market segments of the customer (e.g. hypermarkets), or uses that require a high level of forced contact (e.g. wholesale , hardware stores, specialty trade), and finally Companies whose proximity to efficient roads leading out of the region is important ( freight forwarders , spare parts stores).

Microdevelopment factors

Parcel and building

The macro logic of the structure is supplemented by a 'micro logic'. Both levels of action have a pronounced partial autonomy and both are form-neutral. This means that it is not the random shape that determines its mode of operation, but a structural principle that only uses shape and also overrides inexpedient shapes.

The smallest unit of the city is the parcel. Parcels are parts of urban building land that an owner can dispose of with relative autonomy. Restrictions are given by the legal and neighborhood framework. Within this framework, however, the owner often knows how to stretch, dynamic changes take place on a microscale, such as the change of users and uses, changes to the interior and exterior of the buildings. (The example of Krefeld - in the picture at the bottom right - shows how in the post-war period free-standing buildings in a city with closed street fronts ignored the original context and thus seriously disrupted the structure).

In the case of parcels, we can observe that they tend to be built on more densely in phases of urban growth and rising land values. So there is an increasing utilization. This is also related to the location in the city. With increasing proximity to the core, plots are often built denser and higher. There are exceptions for public buildings and for the renovation of the city center for large-scale uses ( offices , department stores). The compression process can be explained by the fact that open spaces, distances, etc. that were apparently previously considered necessary are finally reduced until a certain minimum of conditions necessary for life is reached. We find this minimum in Arab city plans as well as in those of the late Middle Ages or the 19th century . Since the requirements for the size of parcels and buildings can change over time, especially if the type of use changes, or if an area that was previously on the edge later becomes more central due to urban growth, in addition to the geometric shape and the layout, the The size of the parcels and the size and shape of the buildings are critically important for usability in a changing context.

Hoffmann-Axthelm wrote in the Bauwelt : “The parcel city is a network that carries the content of the city and relates it to them. The individual parcel is the smallest urban unit, the houses, building forms, courtyards, etc. are concrete architectural interior fittings. The basic units can be larger or smaller, even very large and very small. As in biology , it is crucial that these containers exist at all, with their boundaries between inside and outside, their passages and inside-outside effects. The resilience of a city depends on the extent and sophistication of the network. Modern city planning believed that it was sufficient to put ventilated and lighted buildings all around in the area. She saw the parcel division as an old braid that had to be cut off without realizing what services the system provided ... “ According to Hoffmann-Axthelm, the parcel is a distribution grid of different owners, which allows large corporations and property developers to access the city and the resulting monotony avoids an element on which a mixture of functions can take place, a control instrument of urban ecology , a basic social unit, a carrier of typological tradition, but also a historical storage unit and finally a perception unit. Because "in order to be busy, perception needs real separations that include new hires and surprises ."

The parcel and building are therefore the smallest units with a partial autonomy of disposal and - within certain limits - change by owners and users. As a result of this permanent adjustment on the lowest level, the city system is renewed in small steps without the need for central planning processes or decisions. However, not only are corrections carried out, the parcels also function as sensors of an early warning system: the effects of changes in accessibility (traffic routing) or in land values and rents are first felt at the micro level. From here signals are sent to the decision-making bodies, which in turn lead to corrections or fine-tuning of decisions. In this way, the entire urban structure system is in constant interaction between fundamental system decisions and their feedback and correction.

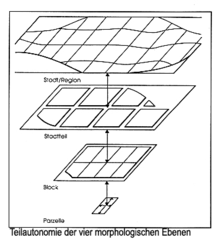

Partial autonomy of urban scale levels

Muratori has worked out a dialectic of four urban morphological levels that have a relative autonomy, but are hierarchically related to one another: These are the building, the quarter, the city and the region, which together form the fabric of the urban morphology. Muratori explains:

“The urban fabric is very inert. Change takes hold more easily on the small scales than on the large ones. Change usually takes place on a small scale, within the scope of the given scope in the buildings, on the property. They are referred to as 'capillary changes', as punctual interventions that use the flexibility of the existing structures. The existing modular systems provide the scope. These are the plot shapes and the house shapes. Changes can be made by adding storeys, building over undeveloped parts of the parcel or by merging parcels. In all cases, the interventions take place within the framework of the predetermined modular system and have a preservative effect on these features. This change does not take place continuously, but discontinuously in different places. The sluggishness of the urban fabric therefore makes it necessary to adapt the change steps when updating the building fabric. The changes to the building must not exceed a certain margin defined by the morphological features of the structure. In certain phases, these small-scale changes are countered by complementary changes in the larger structure, which are not brought about by individual decision-makers but by sovereign planning. This type of shift works over long periods of time. Both processes are not to be regarded as independent of one another. On the contrary, the formation process of settlement structures is an alternation process in which individual practice and collective interventions enter into complementary relationships. "

There are therefore constellations that remain unchanged for centuries without paralyzing the renewal of other elements on other levels of scale; on the other hand, punctual modifications are constantly taking place without all structures being constantly turned inside out. With the concept of the typological process, it can be shown that not only the aggregation of the various settlement components in the space takes place on the basis of a rationally analyzable order, but that the structural change over time and the integration of new elements into the already existing context according to a certain logic and carry it out in a continuity of references. The process-like character of the evolution of types results from the connection of three compelling factors:

- The fact that the different scale levels are nested affects the different characteristics and variation of the different objects.

- The different levels of flexibility with regard to change at each level of scale resist a homogeneous alignment of the system as a whole with the smallest change.

- The fact that settlement structures are the product of a multitude of acting individuals limits the possibilities in which change could take place.

The approach is clearly based on the high cultural importance and homogeneity of the old Italian cities and derives from this in the sense of analysis and design instructions:

- The four levels of scale (building, district, city, region) of the city as well as of building and planning, each of which has its own autonomy and is nevertheless connected to one another.

- Interdependent relationships between these levels, the dialectic between the parts and the whole: the grouping of the houses with one another requires certain combinatorial possibilities from them. Buildings become parts of the neighborhood and the street, neighborhoods become parts of the urban structure, the retroactive influences of which they are exposed to. Likewise, through the interlinking of the levels of scale (house, parcel, quarter, city, territory), each organism is both the starting point and the end of a formation process. Every organism contains elements of lower levels and is itself inserted into an organism of higher levels.

- The typological analysis. It is essential that in the individual periods of urban development, through a filtering process, particularly suitable forms develop for certain construction tasks, which are repeated with slight variations. These types are like the condensate of a certain period.

Continuity and change in the urban layout

Tradition as a mental counterbalance

Times of rapid change can be a mental overload of society. In such times, the continuation of structural and social traditions can be a security platform against the risk of new forms that are still unsettled. The insecure parts of society then seek support in familiar - often outdated - forms. To put it bluntly, one could say that the faster the change in the way of working and living, the more important the inertia of the old routines and forms seems to be as a mental counterbalance, at least in some areas. This was e.g. For example, the 19th century method of masking a familiar decor for the new functions. This was precisely what was criticized for a long time. Although this path has its problems, from today's perspective it must be recognized that the architects of the time were interested in the aesthetic integration of new functions into an existing repertoire of forms in the existing city. Their answers were "ambiguous" in trying to combine new tasks and materials with familiar forms.

The discussion that continues today between representatives of a consistent modernism and representatives of a mediating path that includes the location is - as a look back at the building history of this century shows - both right.

Modernity needs its space, but it is often much more effective in older environments. In this respect, the dialectic between younger and older formal languages is often productive; the consistent, ruthless and massive implementation of modernism, on the other hand, is often problematic (e.g. the rebuilding of Dresden's core city after the Second World War ).

Economy of Continuous Change

Since developments rarely take place abruptly, but rather gradually, an appropriate form of modernization could be seen in a continuous form of renewal. Renewal and change in small steps make it possible to gain experience with the new without giving up too much of the old. The old structures retain their internal logic because they are still dominant. The innovations appear sporadically at first. Reactions to what is available are required of them, which makes them ambiguous in a positive sense. As a result, innovations will not always appear in a pure, but rather in a mediated form. This can make them structurally and socially more compatible. With increasing probation and habituation, contemporary forms can then prevail more consistently.

Innovations as answers to system limits

Every organized system has its own optimum . If the growth (or the intensity of use) goes far beyond this optimum, internal and external bottlenecks, overloads and excessive demands arise, which call the functioning of subsystems or the entire system into question. A situation arises in which it is decided whether a system remains within its limits or whether a higher functional level can be achieved through the use of new technical and organizational means. Innovations in this sense were z. B. the wall rings and bastions to protect the cities, trams , subways and buses to serve the urban structure, water supply , sewage and waste disposal . Today, developments such as traffic-calmed areas or regulations to reduce car traffic in cities can be understood as innovations that are necessary to take the threat of overuse of road spaces and pollutants away from the city system .

History in the city plan

City floor plans are much more durable than the building structures. So are z. For example, traces of Roman roads and the medieval road network are largely preserved in the Cologne floor plan (see picture on the right). This means two things: firstly, the principles of spatial organization were evidently suitable enough to remain in use to this day, and secondly, this part of the city plan is a historical document from earlier periods. Neither the older buildings nor the streets are authentic in detail, but the characteristics have been retained.

This connection between the past and the present is obviously important for societies. No society can only live and act in the now or only in a future-oriented manner. Memories of earlier periods and respect for the achievements of previous generations were part of every culture . Finding identity requires orientation towards the past, present and the future that is emerging. In this respect, the period of reconstruction and structural corrections from 1945 to 1975 resulted in the destruction of historical building structures and their morphological “world” that are painfully recognized today. In many cases, short-lived ideas of modernity were enforced against the bitter resistance of the residents. The results were seldom sustainable.

Urban morphology and models

At all times, humans, as a social species living in groups, have produced their own spatial organization of their living conditions. This organization had to solve the different requirements of climate, security, economic land use, social order and differentiation, representation and the spatial allocation of living and working. Since not only the forms of production, but also the social stratification of society, the forms of representation, living and intercourse have changed significantly over time, it follows that every period that clearly differs in these characteristics is essentially also a period has produced its own urban form. If this is not always evident, a number of factors are responsible. In many European cities, this can be seen through an additive sequence of traces of the urban development models in the city plan, following the growth rings from the inside out . In quick succession we find projects of the garden city movement , the “New Building” of the 20s , the row and row buildings of the 50s-60s and finally the free plastic arrangements of the late 1960s and 1970s. In some cities the city extensions are approaching almost closed rings, in others they concentrate on individual sectors or on a “patchwork” of randomly appearing distributions. Above all, the commercial areas of the post-war period remained without a model, the structures of which were developed by the individual rationality of the investors - and thus according to a random system - and not according to an urban planning concept that also regulates public space.

The readability of the different times in the city plan is used for orientation. Patchwork structures offer a more open pattern to further develop the city in small units. However, because of their lack of order, they also make it easier for investors to access the space and carry the core of anything within them. To some extent, such structures are inevitable. The more homogeneous morphological structures of earlier periods give the urban body support and orientation, the less worrying they are.

Using the example of Dresden's building structure before its destruction (picture on the right) and after reconstruction after 1945, it becomes clear what influence the models of “modernity” had on urban planning. It was only after 1975 that people became more aware that historical city plans preserve the character of a city, even if the buildings are from the present. In the meantime, Dresden has restored the former city plan in the old town - largely with buildings that are partly historic and partly contemporary. What the comparison clearly shows is the “detachment” of the development, the conversion of a dense “pack” of buildings and the uses they contain to a loose, almost suburban development. A fateful misunderstanding of the character of the city promoted worldwide by the Charter of Athens and its application after the Second World War. The mix of uses has always been a core phenomenon in cities. With the horizontal “unpacking” of the originally more vertically assigned mix of uses in the buildings, the cities planned according to this principle lost the core of what defines a city: urbanity , which also always included conflicts, contradictions and areas of transformation . Cities were and are never finished! New answers must always be found to changing conditions. The morphology of the city, consisting of its networks (streets, corridors), its building structures (geometry and density of the building blocks and building areas) and open spaces oppose the change with varying degrees of resistance. Allowing change and still maintaining the areas that shape the city's character is the art of urban development and urban renewal.

See also

literature

- Curdes, Gerhard : Urban morphology as a new research and policy area. In: Seminar reports 24, Ed .: Society for Regional Research, Heidelberg 1988.

- Curdes, Gerhard; Haase, Andrea; Rodriguez-Lores, J .: Urban Structure: Stability and Change . Contributions to urban morphological discussion. Series of publications on politics and planning. Volume 22, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-555-00819-6 .

- Curdes, Gerhard: Urban structure and urban design. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-17-014294-1 .

- Curdes, Gerhard: The development of the Aachen urban space: the influence of models and innovations on the shape of the city. Dortmund sales for building and planning literature, Dortmund 1990, ISBN 3-929797-37-2 .

- Haase, Andrea: The development of Duisburg's urban space: the influence of innovations on spaces and functions. Dortmund sales for building and planning literature, Dortmund 1999, ISBN 3-929797-38-0 .

- Ley, Karsten: Positions on an Urban Space History and Spatium Urbis Genoae . In: Strada Nuova. Typological studies on the architecture of the city of Genoa; Brenner, Klaus Theo , Schröder, Uwe (eds.), Wasmuth, Tübingen / Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-8030-0930-2 , pp. 20–33.

- Ley, Karsten: Methodology of an Urban Space History and Spatium Urbis Catinae. In: Città Nera. Studies on the spatiality of the city of Catania. Schröder, Uwe (ed.), Wasmuth, Tübingen / Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-8030-0934-0 , pp. 30–37.

- Ley, Karsten: Logic of an Urban Space History and Spatium Urbis Neapolis. In: Neapolis. Studies on the spatiality of the city of Naples. Schröder, Uwe (ed.), Wasmuth, Tübingen / Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-8030-0935-7 , pp. 58-64.

- Raith, Erich : Urban morphology - approaches, implementations, prospects , Springer, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-211-83489-3 .

Literature with collections of city plans

- Leonardo Benevolo : The History of the City. 9th edition. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2007 (original title: Storia della città , translated by Jürgen Humburg), ISBN 978-3-593-38492-4 (standard work).

- Jean-Claude Golvin : Metropolises of Antiquity. Theiss, Stuttgart 2005 (original title: L 'antiquité retrouvée , translated by Geneviève Lüscher), ISBN 978-3-8062-1941-8 .

- Charles P. Graves , David Grahame Shane : The Genealogy of Cities. City Atlas with CD-ROM, Kent State University Press, Kent, OH 2009, ISBN 978-0-87338-939-6 ( Shows drawn plans of cities from around the world, English).

- Thomas Hall: Medieval city plans - attempt to provide an overview of the development in Germany and France (= Antikvariskt arkiv , volume 66), Almqvist och Wiksell, Stockholm 1978, ISBN 91-7402-058-7 .

- Thomas Hall: Planning of European capitals: on the development of urban planning in the 19th century (= Kungliga Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Academies: Historie och Antikvitets Akademiens handlingar / Antikvariska series , volume 35), Almqvist och Wiksell, Stockholm 1986, ISBN 91-7402-165 -6 .

- Heineberg, Heinz: Outline of general geography: Urban geography , Paderborn 2001.

- Hotzan, Jürgen: dtv-Atlas Stadt - From the first foundations to modern urban planning , 3rd, updated and ext. Edition. 2004.

- Carsten Jonas : The city and its layout. On the shape and history of the German city after it was demolished and connected to the railway , Wasmuth, Tübingen / Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-8030-0653-0 ; 2nd, expanded edition 2009, ISBN 978-3-8030-0708-7 (with the latest developments).

- Spiro Kostof : The Face of the City - History of Urban Diversity , Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1993.

- ders. The anatomy of the city - history of urban structures , Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1993.

- Frank Kolb : The city in antiquity , Munich 1984, ISBN 3-406-03172-2 .

- Krier, Rob : Urban space in theory and practice (using examples of downtown Stuttgart) , Volume 1 of the series of publications by the Institute for Drawing and Modeling - University of Stuttgart (Ed.), Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-7828-1427-4 .

- Ley, Karsten: The Urban Matrix. Towards a Theory on the Parameters of Urban Form and their Interrelation , FdR, Aachen, 2009, ISBN 978-3-936971-25-5 .

- Lindemann, Hans-Eckhard: City in the square - past and present of a memorable city shape , Bauwelt Fundamente series (Stadtbaugeschichte / Städtebau), Vol. 121, Braunschweig / Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-528-06121-9 .

- Loderer, Benedikt: Stadtwanderers Merkbuch - definition of "urban space" using the example of Fabriano , Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7667-0865-1 .

- Lynch, Kevin: The image of the city , Bauwelt Fundamente series, vol. 16, Ullstein publishing house, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1965.

- Miller, Toni: Thoughts on the Third Dimension in Urban Development - Interplay of Topography and Buildings , Ed. German Academy for Urban Development and Regional Planning, Wuppertal 2003.

- Mueller-Haagen, Inga; Simonsen, Jörn; Többen, Lothar: The DNA of the city. An atlas of urban structures in Germany , Verlag Hermann Schmidt Mainz, 2014.

- Lewis Mumford : The city, history and outlook , volume 1 and 2. 3rd edition, dtv, Munich 1984 (original title: The City in History , translated by Helmut Lindemann), ISBN 3-423-04326-1 (standard work).

- Rauda, Wolfgang: Lively urban development of space - asymmetry and rhythm in the German city , Julius Hoffmann publishing house, Stuttgart no year (foreword 1957), no ISBN.

- Toni Salomon: Building after Stalin: Architecture and urban development in the GDR in the process of de-Stalinization 1954-1960 , Hans Schiller, Tübingen / Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-89930-065-9 (Dissertation TU Chemnitz 2016, VIII, 581 pages with illustrations ).

- Schütz, Franz Xaver: Regensburg and Cologne city plan. A GIS-based study , Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-935052-71-9 .

- Hans Simon: The Heart of Our Cities , Volumes 1 to 7: Drawings of European city centers in the Middle Ages , published by the German Academy for Urban Development and Regional Planning eV, Munich, R. Bacht, Essen 1963–1985, OCLC 769555890 .

- Trieb, Michael: Urban design - theory and practice , Bauwelt Fundamente series (urban development / architecture), Bd. 43, Düsseldorf 1974, ISBN 3-570-08643-7 .

- Valena, Thomas: City and Topography , with Thomas Will, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin 1990

Book title on the genesis of city plans

In Italy there is an excellent book series on the historical development of selected Italian cities and their urban layout, which does not exist in the German-speaking area: Le citta nella storia d'Italia. Published by Cesare De Seta. Publisher: "Editori Laterza". There are: Palermo, Torino, Firence, Genova, Bologna, Venezia, Messina, Padova, Roma, Napoli, Milano, Bari, Perugia, Mantova and others. a. The entire list of titles can be found under “Catalogo” - “Argomento” in the Architettura e Urbanistica section of the Citta d'Italia series.

Urban Morphology journal

An important part of the international discussion on urban morphology is carried out in the English-language journal Urban Morphology . An overview of the most important publications on urban morphology can be found on the ISUF website.

Some selected books with vertical photographs of cities and city sections

- Facio, Mario: Historic city centers of Italy , DuMont Buchverlag Cologne 1980

- Manfred Czerwinski: Aachen from the air , Verlag Wartberg, 1997

- Hanover. Aerial photos of yesterday and today . A comparison by Waldemar R. Röhrbein, Manfred Czerwinski. Wartberg Publishing House, 1997

- Rudolf Schmidt, Manfred Czerwinski: Cologne, aerial photos of yesterday and today , Verlag Wartberg, 1998

- Cologne, the historical-topographical atlas . (Eds. Wiktorin / Blenck / Nipper / Nutz / Zehner). 220 p., Emons Verlag, Cologne 2001

- Andreas Förschler and Manfred Czerwinski: Stuttgart, aerial photos from yesterday and today . Wartberg Publishing House, 1998

- Atlante di Venezia , Salzano, Edoardo (ed.), Marsilio Editori, Comune di Venezia 1989, ISBN 88-317-5209-X

- Link to aerial photographs of German cities ( Memento from February 2, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Link to aerial photos of cities worldwide ( Memento from January 4, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Google Earth has developed into an increasingly better tool for geography and urban exploration in recent years. Using search and zoom functions, city plans and small city sections can be examined quickly and easily. The quality of the map material and how up-to-date it is is very different. But with the effort that Google puts into this field, the quality will improve quickly.

Web links

- Institut der Stadtbaukunst Bremen, stadtbaukunst.com: Dignity of the profane (PDF; 6.92 MB)

swell

- ↑ a b Contents of different volumes of the journal Urban Morphology

- ↑ International Seminar on Urban Form Homepage

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Wolkenkuckucksheim - Cloud-Cuckoo-Land - Vozdushnyi zamok 01/2005 Claus Christian Wiegandt )

- ↑ Karsten Ley: Positions on a history of urban space and Spatium Urbis Genoae. In: Klaus Theo Brenner, Uwe Schröder (Eds.): Strada Nuova. Typological studies on the architecture of the city of Genoa. Wasmuth, Tübingen / Berlin 2015, pp. 20–33.

- ↑ Nik Cohn: The Heart of the World . Munich / Vienna 1992.

- ↑ Hoffmann-Axthelm, Bauwelt 48, 1990, p. 2488ff

- ↑ S. Malfroy: Small glossary on Saverio Muratori's urban morphology . In: Arch + 85, 986, pp. 66-73.

- ↑ Malfroy, 1986, pp. 191f

- ↑ www.laterza.it

- ↑ Bibliography

- ↑ stadtbaukunst.org (August 24, 2017)