Sinan

Sinan or Sinān , probably with full name Yusuf Sinan (or Sinanüddin ) bin Abdullah (or Abdülmennan , Abdurrahman , Abdülkerim , born around 1490 probably in Ağırnas near Kayseri ; died on July 17, 1588 in Istanbul ) was the most important Ottoman architect at the time of the Sultans Selim I , Suleyman I , Selim II and Murad III. In this capacity he received honorary degrees such as Koca Mimar Sinan Ağa ( Ottoman قوجه معمار سنان آغا İA Ḳoca Miʿmār Sinān Āġā ). He became generally known under the short name "Architect Sinan" (Mimar Sinan) .

The work of Sinan, who also worked as a civil engineer and town planner , is considered to be the highlight of classical Ottoman architecture . Sinan's importance is made clear by designations such as "Euclid of his era" or "Michelangelo of the Ottomans" by contemporaries and specialist literature. He is considered one of the greatest architects of all time. Some of its mosques are considered by art historians to be the most perfect of the pre-industrial times in their congruence and harmony of internal and external effects.

Life

Sinan's exact date of birth is unknown. The incomplete and sometimes contradicting information about his family and his life is largely based on written oral communications from Sinan by his friend, the poet Mustafa Sâ'î Çelebi , as well as the correspondence from his time as general builder , his foundation charter ( Vakfiye ) and the epitaph on his Tomb .

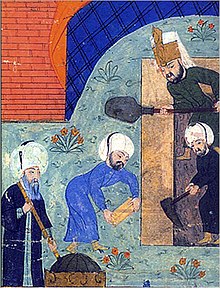

Sinan grew up as the son of Greek Orthodox Christians who were possibly Turkish-speaking , in the Cappadocian village of Ağırnas near Kayseri and was probably baptized in the name of Joseph or Yusuf. Whether he was born in Ağırnas is just as unknown as the ethnic origin of his family, which could have been of Greek or Armenian origin. In Ağırnas he possibly became a stonemason . He came to Istanbul as a young man in 1512/13/14 through an unusually late boy harvest and was trained as a master carpenter as well as in the military ( acemi ocağı ). In the following decades he took part in most of the campaigns under the sultans Selim I and Suleyman I ( Çaldıran , Damascus, Cairo, Belgrade, Rhodes, Mohács , Vienna, Tabriz, Baghdad, Corfu, Apulia, Moldova, etc.) and learned thus know the most diverse architectural traditions.

During the capture of Belgrade in 1521 he was accepted by the Janissaries under the name Sinān b (in) ʿAbdüʾl-Mennān . From 1523 to 1526 he was Atlı Sekban (or Atlı Seğmen = mounted "dog guard"; mounted hunter; Janissary officer) and after 1526 he was promoted to Yayabaşı (infantry captain ). He then commanded the 82nd Corps ( ocak ) as Zemberekçibaşı (= commander of the artillery) and was appointed Haseki (colonel of the imperial bodyguard ) after the Iraq campaign in 1535 . At the same time, he served as a military engineer from the 1920s onwards, later his talent in building fortresses, bridges, etc. earned him the post of chief mechanic in the 1530s. Between the campaigns he also erected some civil buildings, so that in 1537/38/39, after the death of his predecessor Acem Ali, he received the title "Ser-Mimâr-ı Mimârân-ı Hassâ" (= head of the court builders).

With the construction or completion of the Haseki Hürrem Sultan Mosque (1538/39) one of the most remarkable careers in architectural history began. His first major work was the Şehzade Mosque in Istanbul (built 1543–1548). Other major works are the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul (1550–1557) and the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne (1567 / 68–1574 / 75). The otherwise unconfirmed opinion goes back to the travel writer Evliya Çelebi that Sinan himself described these three mosques as “apprentice's piece” (Şehzade mosque), “journeyman's piece” (Suleymaniye mosque) and “masterpiece” (Selimiye mosque). But even between these major works, numerous secular and religious buildings of exquisite quality and originality were built. After the Selimiye Mosque, he created numerous mosques that again showed new solutions for over-coupling on hexagonal or octagonal support systems.

As chief architect of the court building authority, Sinan was not only responsible for the building structure, but also often designed the interior, for example by accentuating tile panels . During his 50-year tenure, due to the enormous construction work, the number of architects under him increased from 17 to over 30 - more than a third were unconverted Christians. In addition, he trained 250 students in the course of his 50 years as chief architect, of which one student, Yusuf, served under the Mughal ruler Akbar I the Great in India. His student Mimar Hayreddin was the architect of the old Stari most bridge over the Neretva in Mostar . The planning of the neighboring, smaller Kriva Ćuprija bridge over the Radobolja brook is attributed to him.

Little is known about his family. The deed of his foundation established between 1583 and 1585 shows that he was married, had a son who had died during Sinan's lifetime and was known as a martyr, two daughters, a grandson, a Christian brother and a brother who had converted to Islam, as well as two nephews and three great nieces .

Sinan died in 1588 and is buried on the northern edge of the Külliye of the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul in a simple Türbe designed by himself .

In memory of the great master builder, the Mimar Sinan University in the Fındıklı district of Istanbul was named after him.

Buildings

There are five autobiographies or catalog raisonnés in which Sinan's buildings are listed: Teẕkiretüʾl-Ebniye, Tuḥfetüʾl-Miʿmārīn, Adsız Risale, Risāletüʾl-Miʿmāriyye and Teẕkiretüʾl-Bünyān . These documents, which go back to Sinan himself, list not only the structures Sinan designed and built, but also works for which he was responsible for the renovation, such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

In total, these directories contain an oeuvre of 471 to 477 buildings. Of these 477 buildings, 29 cannot be identified or assigned to Sinan, 172 - mostly wooden structures - have been destroyed due to fire, earthquakes, overbuilding, entosmanization, etc., 49 have been fundamentally renovated so that Sinan's building fabric is barely there, 23 only exist still as a ruin (as of 1985). 204 of Sinan's buildings are originally preserved.

Of the 477 buildings, 319 are in Istanbul and at least 50 others are within 250 km. Some of his buildings are likely to be based only on Sinan's plans, he left the execution on site to his assistants. This conclusion can be drawn if one examines structural details that sometimes show a somewhat unsatisfactory solution (such as the Molla Çelebi mosque ). Sinan can hardly be ascribed to their execution, as he gives typical architectural answers for these details in other important buildings. Other buildings, on the other hand, were not personally supervised by him on site because he would hardly have had time for all the necessary trips to the borders of the world empire (such as the Tatar Khan mosque / Ukraine) or it is known that assistants were sent from Istanbul were or local builders took over the execution. We know, however, that Sinan traveled to Mecca , for example , where he supervised work.

Some smaller structures are not on the lists, such as fountains, certain schools, shops, etc. Some larger structures that are not on the lists are still considered to have been built by Sinan (such as two of the minarets of Hagia Sophia and the poor kitchen the Haseki Hürrem Külliye).

All in all, Sinan is valued very highly: “[...] in the scope of his oeuvre [he] was not surpassed by any other architect in any country or any culture, and hardly anyone was able to implement his ideas as consistently as he was, and no one found such generous builders as the sultans and statesmen of the Ottoman Empire. "

The enormous number of buildings is also due to the fact that the Ottoman founders mostly had non-profit buildings built next to a Friday mosque . This is how a whole socio-economic building complex, called Külliye , was created. There were almost endless financial resources available, which in the case of the sultan's mosques and külliyen were supposed to consist exclusively of booty money and tribute payments from the "infidels".

The structures are broken down as follows (in brackets the numbers of Sinan's buildings, which today are preserved in their original structure):

- Friday mosques (Cami): 107 (64)

- Everyday mosques ( mescite ): 52 (7)

- Mausoleums ( Türbe ): 45 (32)

- Universities ( Madrasa ): 74 (35)

- Koran schools ( Darülkurra ): 8 (4)

- Primary schools ( Sıbyan Mektebi ): 6 (5)

- Dervish monasteries ( Tekke ): 6 (2)

- Hospitals ( Darüşşifa ): 3 (3)

- Poor kitchens ( İmaret ): 22 (7)

- Caravanserais / Hane: 31 (11)

- Palaces ( Saray ): 38 (2)

- Pavilions ( Köşk ): 5 (1)

- Magazines: 8 (2)

- Public baths ( Hamam ): 56 (13)

- Bridges: 9 (9)

- Aqueducts / hydraulic structures: 7 (7)

Total: 477 (204 still preserved today)

Sinan and his biographer Mustafa Sâ'î Çelebi stated that the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul served Sinan as a great model that he tried to surpass. Sinan was also inspired by other buildings: in Istanbul the church of Hagioi Sergios and Bakchos ( Küçük Ayasofya Camii ), the Sultan Beyazıt Mosque , the mosque Mehmed the Conqueror and the Zincirlikuyu Mosque, in Bursa the Great Mosque and in Edirne the Üç- Şerefeli Mosque .

One of the characteristic features of Sinan's buildings is the inclusion of the urban context and the surrounding area, both in the building design of the complex and in the design of the external appearance of the facades.

Buildings in and around Istanbul

- Haseki Hürrem Sultan Complex ( Haseki Hürrem Sultan Külliyesi ) - Sinan's probably first major commission as a court architect. The one-dome mosque was completed in 1538/39 - later it was expanded to include a college (1539/40), a poor kitchen (1550) and a hospital (Darüşşifa. 1557 (?); At least after 1550) - the latter a unique, very original building with an octagonal courtyard, which is interpreted as reminiscent of ancient Roman buildings. map

- Barbaros-Hayrettin-Pascha-Mausoleum - 1541/42. map

- Mihrimah Sultan Mosque ( İskele Camii , Mihrimah Sultan Camii ) in Üsküdar - 1543 / 44–1547 / 48. The double portico used here will from now on appear in variations in numerous mosques. Four-pillar mosque with three half-domes. map

- Şehzade Mosque ( Şehzade Mehmet Camii , Prince Mosque ) - 1543–1548. An early masterpiece, according to Evliya Çelebi by Sinan himself as his “apprentice piece ”, in Sinan's autobiography Teẕkiretüʾl-Bünyān, on the other hand, referred to as “a building like paradise” (binā-yı cennet-nişan-ı). The mosque is Sinan's first monumental building, probably planned as the actual first "Sultan Suleyman Mosque". It marks a turning point in Ottoman architecture thanks to the model, centrally symmetrical four-pillar system with four half-domes. This is where the later typical dome cascade, made up of the main dome, half-domes and third-domes, appears for the first time. The courtyard becomes an architectural part of the whole. In addition to all monumentality, it preserves a human scale, achieved for example by the outer galleries. In the Şehzade Mosque, Sinan experiments with an ornamentation of the surface that is reminiscent of Selschuk ornamentation. A few years later, he no longer repeats this architectural decoration. map

- Sultan Selim I Medrese ( Yenibahçe Selim Medresesi , Halıcılar Köşkü ) - 1548/49. Typical U-shaped medrese. map

- Rustem-Pascha-Medrese - 1550. College with octagonal inner courtyard. map

- Rustem Pasha Caravanserai ( Rustem Paşa Kervansarayı, Kurşunlu Han ) - 1544–1550. Narrow Han, in whose open courtyard a staircase leads to the upper floor. map

- Hadim Ibrahim Pasha Mosque ( Hadim Ibrahim Paşa Camii ) - 1551. One-dome mosque. map

- Sinan Pasha Mosque ( Sinan Paşa (Beşiktaş) Camii ) - 1554–1555 / 56. Six-pillar mosque with four diagonal domes and numerous strong bonds from the Üç Şerefeli mosque in Edirne. map

- Haseki Hürrem Sultan Hamam ( Ayasofya Hürrem Sultan Hamamı ) - 1556/7. Twin bath complex, mirrored on the west-east axis and 75 meters long. map

- Suleymaniye Complex ( Sultan Suleyman Külliyesi ) - 1550–1557. Another masterpiece, also in terms of urban development, as the complex accepts the topography with the hill and the streets as a challenge and comes up with original solutions. According to Evliya Çelebi by Sinan himself, the mosque is called his “journeyman's piece ”, whereas in Sinan's autobiography Teẕkiretüʾl-Bünyān it is referred to as “a joyful abode equal to paradise” (Cennet-āsā bir maqām-ı dilgüşa). The third and fourth madrasahs ( râbi and sâlis medresesi ), completed in 1558/59, with their terraces facing the Golden Horn , are also masterly . The monumental Külliye has a similar urban and imperial claim as the Külliye around the mosque Mehmed the Conqueror . The Suleymaniye Mosque is a four-pillar mosque with two shield walls and two axial half-domes, similar to the Sultan Beyazıt Mosque and Hagia Sophia. Sinan, however, arrives at a completely different model of a central building and a congruence of external and internal effects. Inside, the famous Bolus Red is used in the İznik tiles for the first time . Sinan's tomb is just outside the mosque walls. map

- Şehzade-Cihangir Mosque ( Şehzade-Cihangir Camii ) - 1559–1560. The complex built for Cihangir, the son of Sultan Suleyman I, who died in 1553, in Tophane included the mosque, a primary school, a soup kitchen and a dervish convent. The modest dimensions corresponded to the minor importance of the physically handicapped prince in the dynastic hierarchy. The mosque had a hipped roof, the minaret only a gallery. A garden plot served as building site, on which Cihangir had built a pavilion and hoped that an elegant prince's mosque could be built on this exposed spot. Among other things, two fires ensured that nothing of the entire system was preserved. Instead, a new building from 1889–1890 rises here.

- Molla Çelebi Mosque ( Fındıklı Camii , Molla Çelebi Camii ) - 1561 (?) Or around 1570–1584. Six-pillar mosque with four diagonal domes. Example of a mosque planned by Sinan, the execution of which he probably did not personally monitor, as some structural details show. map

- Rustem Pasha Mosque ( Rustem Paşa Camii ) - around 1561–1563. A first masterful eight-pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes. The mosque rises above its surroundings on substructures and thus offers space for shops under the prayer room. Atypical for a mosque, it is lavishly furnished with Iznik tiles, which are among the most beautiful examples at the beginning of the heyday of Ottoman ceramic production. map

- Mağlova Aqueduct ( Mağlova / Moğolağa / Muğlava Kemeri ) - 1553–1564. Probably the most beautiful aqueduct of the Sinan's water supply system. 36 meters high, 258 meters long. The typical two-dimensional, arched wall front is expanded by a third dimension in an expressionist manner through horizontal structures, whereby the statics of the building with its tensile forces become visible in an original way. This masterpiece of engineering is part of a new water supply system with aqueducts, pipes, dams, cisterns, etc., commissioned by Sultan Suleyman for the rapidly growing capital, with a total cost of 40,263,063 Akçes . map

- Long aqueduct ( Uzun / Petnahor Kemer ) - 1553–1564. 711 meters long, 26 meters high. map

- Bent aqueduct ( Eğri / Kovuk Kemer ) - 1553–1564. 342 meters long, 35 meters high. Surname

- Mihrimah Sultan Mosque ( Mihrimah Sultan Camii ) in Edirnekapı - 1562 / 63–1565 or 1570 (?). This light-flooded masterpiece of a four-pillar mosque is equipped with four shield walls. map

- Sultan Suleyman Mausoleum - 1566/67. Remarkable mausoleum inspired by the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, the mausoleum of the Roman emperor Diocletian in Split (Croatia) and by Rum-Seljuk tower tombs. It has a double-skinned dome, which is rarely used in Ottoman architecture, as well as a splinter of the black stone from the Kaaba (Mecca) in the entrance area . map

- Sokollu-Mehmet-Pascha-Medrese in Eyup - 1568/69 map

- Kara Ahmed Pasha Mosque ( Kara Ahmet Paşa Camii ) - after 1558, perhaps 1565–1571 / 72. It is a six-pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes to span the rectangular space, similar to the model of the Üç-Şerefeli mosque in Edirne, but with a completely different effect. map

- Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Complex ( Kadırga Sokollu / Sokullu Mehmet Paşa Külliyesi ) in Kadırga - around 1567 / 68–1571 / 72. It is a six-pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes and one of the most beautiful examples of a successful combination of the building structure with the decoration with tiles and paintings. Some of the most beautiful tiles and some of the most beautiful Ottoman stone glass windows adorn this Sinan's masterpiece, as do two slivers of black stone from the Kaaba in Mecca. Sinan includes the hill on which the complex stands in his construction plan by providing the entrance with a staircase on which the lecture hall is enthroned. This shows the increasing complexity of the solutions found, a high degree of spatial homogeneity, in which the transverse rectangular floor plan is retained, but the verticality is emphasized: an innovation in Islamic architecture . map

- Piyâle Pascha Mosque ( Piyâle (Mehmet) Paşa (Tersane) Camii ) - around 1565–1573 / 74 (?), At least before 1578. Sinan's experiment with the Ulu mosque-type with several smaller domes. Here we find some of the most beautiful Iznik tiles from the heyday of production. map

- Sultan Selim II Mausoleum - 1576/77 Here Sinan repeats the plan of the Selimiye Mosque in a simplified manner. map

- Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque ( Azapkapı Camii , Sokollu / Sokullu Mehmet Paşa Camii ) in Azapkapı - around 1573–1577 / 78. A small-scale variation on the Selimiye Mosque. The eight-pillar mosque was built on substructures, located directly on the Golden Horn, with echoes of palace architecture in the exterior. Inside, some of the most beautiful Iznik tiles adorn this little masterpiece. map

- Bedchamber of Sultan Murad III. ( Sultan Murad Köşkü ) in the Topkapı Palace - 1578/79. One of the most beautiful halls in the palace with exquisite Iznik tiles. map

- Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque ( Tophane Camii , Kılıç Ali Paşa Camii ) - 1578–1580 / 81. Although this four-pillar mosque with two axial half-domes is listed in Sinan's work lists, due to the architectural language it is controversial whether the plan came from him himself. The diverse quotations from Hagia Sophia almost seem as if he had taken the Hagia Sophia plan to correct the inadequacies it contained with this mosque. map

- Şemsi Ahmed Pasha Complex ( Şemsi Ahmed Paşa Camii ) in Üsküdar - 1580/81. Picturesque one-domed mosque on the banks of the Bosporus. map

- Valide Sultan Complex ( Valide (Nurbânu) Sultan Külliyesi , Atik Valide Camii ) in Üsküdar - 1571–1583. Extended 1584 / 85-86. This six-pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes forms the center of Sinan's second largest complex after the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul. With its staggering of the various buildings and courtyards, this complex is reminiscent of the Topkapı Palace . map

- Kazasker İvaz Efendi Mosque ( (Kazasker) Ivaz Efendi Camii ) - 1586. An example of a mosque that is not mentioned in the works lists, but “the building breathes the spirit of Sinan […]” and is therefore often it personally attributed. Location on the land wall is quoted by Byzantine masonry. Six-pillar mosque. map

- Zal Mahmut Pascha complex ( Zal Mahmut Paşa Külliyesi ) - from 1580 or 1577–1590 (?). One of Sinan's most experimental works. The nearby land wall probably inspired him to design the outer walls with their alternation of brick and stone, and the hilly location to the asymmetrical distribution of the buildings in the complex. Four-pillar mosque. map

Buildings in Edirne

- Kanuni Bridge - 1553–1554. map

- Yalnizgoz Bridge - 1567. Map

- Rustem Pasha Caravanserai - 1560/61 (?). map

- Adalet Kasrı - 1561

- Sokollu-Mehmet-Pascha-Hamam - 1568/69. map

- Semiz Ali Pasha Bazaar - 1568/69. Han with 126 stores and 300 meters in length. map

- Selimiye Complex , ( Selimiye Külliyesi ) - 1567 / 68–1574 / 75. According to Evliya Çelebi, Sinan called this eight-pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes his “masterpiece”. Here Sinan has designed a sophisticated support system that has no predecessor, neither in the Roman, Byzantine nor in the Iranian architectural tradition. For the first time, the complex is grouped symmetrically in the axial direction among Sinan's larger complexes. Here the end point of Sinan's lifelong search for the perfect central building has been reached. All structural elements are subordinate to the huge dome. There is a perfect unity of internal and external effects in this highly developed work of Sinan. In addition, the finest interior design ingredients decorate the prayer room, such as Iznik tiles from the artistic and manual heyday of the manufactories. map

Other structures in Europe

- Bosnali Mehmed Pasha Mosque in Sofia ( Bulgaria ) - 1547/48. One-dome mosque, rebuilt into a church by Jurdan Popow and Petko Momchilow between 1899 and 1903 , and extensively converted inside and out. map

- Juma Jami Mosque in Evpatoria ( Ukraine ) - 1552 (?). Four-pillar mosque with a semi-dome over the mihrab . map

- Karađozbeg Mosque ( Karagöz Mehmed Paşa Camii ) in Mostar ( Bosnia and Herzegovina ) - 1557/58. One-dome mosque. map

- Kanuni Sultan Suleyman Bridge (Büyükçekmece Bridge) in Büyükçekmece ( Turkey ) - 1565–1567 / 68. A 638 meter long masterpiece of engineering, erected on difficult, swampy terrain. Sinan therefore distributes the weight of this bridge over a large area and divides it into four bridge sections with a technical sophistication that allowed the bridge to survive almost undamaged for 400 years. map

- Sokollu Mehmet Pasha complex in Lüleburgaz ( Turkey ) - 1565–1569 / 70. This four-pillar mosque is part of a complex strategically built on one of the Reich's arteries , which was primarily intended to serve travelers and trade. The individual structures are not very spectacular, but the construction plan is remarkable, because here the buildings are grouped around the two main axes for the first time. map

- Semiz Ali Pasha Mosque in Babaeski ( Turkey ) - from the 1560s, maybe 1569–1575. In this six-pillar mosque with four diagonal half-domes, Sinan perfects the hexagonal principle. The space and the structural elements form a unit. map

- Drina Bridge ( Sokollu-Mehmet-Pascha Bridge ) in Višegrad ( Bosnia and Herzegovina ) - 1571–1577 / 78. In contrast to the Kanuni-Sultan-Süleyman Bridge, strong horizontal forces of the river act on the bridge, which Sinan encountered with water-dividing projections similar to a ship's bow. 185 meters long. map

- Muradie Mosque ( Muradiye Camii ) in Vlora ( Albania ) - 1537. One-domed mosque. map

Other structures in Asia

- Tekkiye Süleymans ( Takiyya Sulaymaniyya , Sultan Süleyman Mosque, Tekkiye Mosque, Sultan Süleyman Dervish Monastery) in Damascus ( Syria ) - 1554/55 or 1554–1558/59. Medrese completed in 1566/67. The alternation of layers of light and dark stones in this single-dome mosque shows the influence of the local building tradition. The 100 by 150 meter building complex was used by travelers and pilgrims, among other things, as it was on one of the important transit routes. map

- Sultan Selim II Mosque in Karapınar - 1560–1563 / 64. One-dome mosque with a generously dimensioned complex. Coordinates: map

- Behram Pasha Mosque in Diyarbakır - around 1564 / 65–1572 / 73 - the color changes of the rows of stones in this single-dome mosque show local building traditions.

- Sokollu Mehmet Pasha complex in Yakacık (Payas) around 1567–1574 / 75. Rare cruciform plan of a mosque.

- Sultan Murad III Mosque in Manisa - 1583–1586 / 87. Construction probably not supervised by Sinan on site, but by his students Mahmud Ağa and Mehmed Ağa. T-shaped mosque with three curved roofs instead of domes.

- Lala Mustafa Pascha caravanserai in Ilgin - 1584 (?). The extraordinary double caravanserai is part of a Külliye. The associated one-dome mosque was inaugurated in 1576/77.

- Khosreviye complex ( Hüsreviye Külliyesi ) in Aleppo (Syria) - 1546. One dome and several smaller domes.

- Adlijje Complex ( Adliye Külliyesi , Dukaginzâde Mehmet Pasha Mosque) in Aleppo - 1556. Several small domes and a large ornate main entrance.

See also

- Mosques in Istanbul (list, sorted by district)

literature

- Augusto Romano Burelli , Paola Sonia Genaro: The mosques of Sinan . Tübingen 2008

- Howard Crane, Esra Akin, Gülru Necipoğlu: Sinan's Autobiographies: Five Sixteenth-Century Texts. Leiden 2006

- German Architecture Museum (Ed.): Becoming Istanbul . Frankfurt 2008

- Ernst Egli : Sinan. The builder of the Ottoman heyday . Erlenbach-Zurich, Stuttgart 1976 ISBN 3-7249-0476-2 .

- John Freely : Istanbul. A leader . Prestel, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-7913-0098-9 .

- Aptullah Kuran: Sinan. The Grand Old Master of Ottoman Architecture. Washington DC / Istanbul 1987

- Wolfgang Müller-Wiener : Pictorial dictionary on the topography of Istanbul. Tuebingen 1977

- Gülru Necipoğlu: The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton 2005

- Luca Orlandi: Il paesaggio delle architetture di Sinan. Istanbul 2017, ISBN 978-605-9680-62-2

- John Marshall Rogers: Sinan . Oxford 2006, ISBN 1-84511-096-X

- Heinz Jürgen Sauermost, Wolf-Christian von der Mülbe: Istanbul mosques . Munich 1981

- Metin Sözen: Sinan - Architect of Ages. Volume 1. Istanbul / Ankara 1988

- Metin Sözen, Suphi Saatçı: Mustafa Sai Çelebi: Mimar Sinan and Tezkiret-ül Bünyan. Istanbul 1989

- Henri Stierlin: Turkey. From the Seljuks to the Ottomans. Cologne 1998

- Ulya Vogt-Göknil : Sinan . Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-8030-0156-0

- Stéphane Yerasimos: Constantinople. Istanbul's historical heritage . Cologne 2000

items

- Maurice M. Cerasi: Place and Perspective in Sinan's Townscape . (PDF; 8.14 MB) In: Environmental Design. Journal of the Islamic Environmental Design Research Center 1-2, 1987, pp. 52-61

- Stefan Giese: Mimar Sinan Published in the World Wide Web (PDF). In: Karl-Eugen Kurrer , Werner Lorenz , Volker Wetzk (eds.): Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History . Neunplus, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-936033-31-1 , pp. 697-704.

- Godfrey Goodwin: Sinan and City Planning . (PDF; 6.94 MB) In: Environmental Design. Journal of the Islamic Environmental Design Research Center 1-2. 1987. pp. 10-19

- Klaus Kreiser : Sinan . In: Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe . Volume 4. Munich 1981, p. 127 f.

- Aptullah Kuran: Form and Function in Ottoman Building Complexes . (PDF; 6.17 MB) In: Environmental Design Journal of the Islamic Environmental Design Research Center 1-2 , 1987, pp. 132-139

- Aptullah Kuran: Sinan the Magnificent. The work of the great Turkish architect lives on, four centuries after his death . In: UNESCO Courier . March 1988.

- Gülru Necipoğlu: Challenging the Past: Sinan and the Competitive Discourse of Early-modern Islamic Architecture . (PDF; 2.76 MB) In: Muqarnas. An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture . 10, 1993, pp. 169-180

- Gülru Necipoğlu-Kafadar: The Süleymaniye Complex in Istanbul. In terms of interpretation . (PDF; 6.2 MB) In: Muqarnas. An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture . 3, 1985, pp. 92-117

Web links

- Exhibition with floor plans, side views and drawings of Sinan's buildings in the Istanbul Museum of Architecture

- Sinan's biography on archnet.org

- Sinan. In: Encyclopædia Britannica . (English).

- Sinan: A Great Ottoman Architect and Urban Designer . Foundation for Science Technology and Civilization, muslimheritage.com, June 3, 2007

- Giese, Stefan: Mimar Sinan (1490–1588). In: Great Engineers , 2008.

- Francine Giese-Vögeli: Sinan between vision and commissioned work . bauforschungonline.ch, June 7, 2006

- Mimar Sinan and his works (Turkish)

- Website in memory of Sinan of the Republic of Turkey (+ documentary film) (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu, Princeton 2005, pp. 131f.

- ↑ Cafer Çelebi: Risale-i-mimariye . 1623.

- ↑ Attilio Petruccioli (Ed.): Mimar Sinan: The Urban Vision. Environmental design. in: Journal of the Islamic Environmental Design Research Center 1-2 1987. on archnet.org ( Memento of the original from May 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Doğan Kuban: The Style of Sinan's Domed Structures . ( Memento of the original of June 24, 2004 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 5.2 MB) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Muqarnas. An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture . 4, 1987, p. 77.

- ^ Franz Babinger: The Turkish Renaissance. Comments on the work of the great Turkish master builder Sinan . In: Contributions to the knowledge of the Orient and sources for Ottoman art history , in the yearbook of Ottoman art . 1924.

- ^ Sheila S. Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom: The art and architecture of Islam - 1250-1800. New Haven et al. a. 1995, p. 218.

- ↑ a b Howard Crane, Esra Akin, Gülru Necipoğlu: Sinan's Autobiographies: Five Sixteenth Century text. Leiden 2006.

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu, Princeton 2005, pp. 147–152; John Marshall Rogers, Oxford 2006, p. XVf.

- ^ Britannica.com

- ↑ JM Rogers: Sinan. (Makers of Islamic Civilization). New York / London 2007. p. 11.

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu, Princeton 2005, pp. 129-131.

- ^ Talbot Hamlin: Architecture Through the Ages . Putnam Adult. 1953, p. 208. Benjamin Walker: Foundations of Islam: The Making of a World Faith . Peter Owen Ltd. 1998, p. 275.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia Britannica; A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information . Encyclopaedia Britannica. New York 1910, p. 426.

- ↑ John Marshall Rogers, Oxford 2006, p. 11

- ↑ Stéphane Yerasimos: Constantinople. Istanbul's historical heritage. Cologne 2000, p. 253. Oylar Saguner: The Selimiye Mosque and the appearance of the Ottoman court architect Sinan - a cultural-historical consideration of the development of Ottoman architecture in the 16th century . ( Memento of the original from January 20, 2012 in the Internet Archive ; PDF) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Dissertation. Duisburg / Essen 2005. p. 23.

- ↑ a b c d Gülru Necipoğlu, Princeton 2005, p. 145.

- ↑ Aptullah Kuran: Ottoman Classical Mosques in Istanbul and in the Provinces. ( Memento of the original from May 26, 2006 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 1.5 MB) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Margaret Bentley Sevcenko (Ed.): Theories and Principles of Design in the Architecture of Islamic Societies . Cambridge MA 1988.

- ↑ Mimar Hajrudin on the Structurae website .

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu, Princeton 2005, p. 148.

- ↑ Stéphane Yerasimos: Constantinople. Istanbul's historical heritage . Cologne 2000. p. 280; Encyclopaedia of Islam . Brill, Leiden 1997. p. 629.

- ↑ a b Aptullah Kuran: Sinan: The Grand Old Master Of Ottoman Architecture. Washington DC / Istanbul 1987.

- ^ John Freely: Istanbul . Munich 1986. p. 585.

- ↑ Heinz Jürgen Sauermost, Wolf-Christian von der Mülbe: Istanbul Mosques . Munich 1981, p. 28.

- ^ 945 nd Hijra . The date of the inauguration of the mosque is always taken here for a complex

- ^ Howard Crane, Leiden 2006, p. 144.

- ↑ Semester paper Yavuz Sultan Selim Medrese ( Memento of the original from June 8, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Howard Crane, Leiden 2006, p. 150.

- ↑ Gülru Necipoğlu, Princeton 2005, pp. 203 f.

- ^ Henri Stierlin: Turkey. From the Seljuks to the Ottomans . Cologne 1998, p. 178.

- ↑ Fountain in the Ottoman capital İstanbul on the website of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism

- ↑ Heinz Jürgen Sauermost, Wolf-Christian von der Mülbe: Istanbul Mosques . Munich 1981, p. 198.

- ↑ Karapınar Sultan Selim Külliyesi'nde yolculara mahsus mekanlar ve vakıfları in Osmanlı Araştırmaları (Turkish)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sinan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Mimar Sinan; Koca Mimar Sinan Ağa |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Ottoman architect |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around April 15, 1489 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ağırnas at Kayseri |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 17, 1588 |

| Place of death | Istanbul |