al-Haram mosque

| al-Haram mosque | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Coordinates : 21 ° 25 ′ 21.1 ″ N , 39 ° 49 ′ 34.2 ″ E | |

| place | Mecca |

| Laying of the foundation stone | 638 |

| Direction / grouping | Islam |

| Architectural information | |

| Details | |

| capacity | Two million (planned) |

| Property | 400,000 m² |

| Minarets | 13 (planned) |

| Minaret height | 89 m |

The al-Haram Mosque ( Arabic المسجد الحرام al-Masjid al-Harām , DMG al-masǧid al-ḥarām ), also known as the Holy Mosque and Great Mosque , in the Saudi Arabian Mecca is the largest mosque in the world. Even before the Prophet's Mosque in Medina and the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, it is considered the most excellent mosque in Islam . In their courtyard are the Kaaba , the central sanctuary of Islam, the Zamzam fountain and the Maqām Ibrāhīm. A special feature of the al-Harām mosque is that not only prayer and chutba take place here, as in other mosques , but also the tawāf , i.e. the ritual around the Kaaba. According to the Manāsik rules, anyone who enters the al-Harām mosque must first perform a tawāf to greet the Kaaba.

The building history of the al-Haram mosque goes back more than 1,300 years. The most important expansion steps took place in the early Abbasid period in the 8th to 10th centuries, during the Ottoman period in the 16th century and from 1955 under Saudi rule. The Masʿā, i.e. the ritual running route between as-Safā and al-Marwa , has also been part of the al-Harām mosque since the 1960s . The current structure extends over an area of 400,000 m² - including the inner and outer prayer areas - and can accommodate more than a million believers during the Hajj . The mosque is currently being expanded again; after completion of the construction work it will have a total of 13 minarets . Since the previous building was almost completely demolished during the Saudi redesign of the mosque, the earlier building history can only be reconstructed using text and a few image sources. From the 16th to the 18th centuries, depictions of the al-Haram mosque were a popular motif in Islamic art .

Numerous hadiths underline the high religious value of ritual prayer in the Holy Mosque. Its organization, however , has repeatedly caused problems and has been reformed several times due to the existence of different Islamic schools of instruction , which provide different ritual regulations for prayer and which sometimes compete with one another. In addition, the Holy Mosque has been a place for the cultivation of the religious sciences of Islam since the early days of Islam. The term Haram is also used as a short form for the al-Haram Mosque , but the actual Haram of Mecca is a considerably larger district, which covers an area of around 554 square kilometers around the city. The al-Haram mosque has been undergoing extensive renovation and expansion since 2007.

Building history

Earliest construction history: the layout of a building around the Kaaba

Regarding the earliest architectural history of the Holy Mosque, the Meccan historian al-Azraqī (died 837) quotes a report by the Meccan scholar Ibn Juraidsch (died 767). According to this, the Meccan sanctuary was originally not surrounded by walls, but enclosed on all sides by houses with gates between them through which one could get to it. The Banū-Shaiba gate, which was located in the courtyard of the mosque until the late 1950s and is named after the Kaaba guard Shaiba ibn ʿUthmān (died 677) and his descendants, marked the location of the most important of these passages. It is said to have been used by the Prophet Mohammed when he went to the Meccan sanctuary.

As the space in front of the Kaaba became too narrow for the people over time, the caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb (r. 634–644) bought some of the closest houses and tore them down. Since some owners did not give up their houses voluntarily, he expropriated them and deposited the money for them in the treasury of the Kaaba, where they gradually picked it up. He justified his actions to them by saying that the Kaaba had been there earlier and that they had wrongly built up their courtyard with their houses. ʿUmar also had a low wall built around the Kaaba. In doing so, he laid the foundation stone for the al-Haram mosque as an independent building. According to at-Tabarī , this took place in the Rajab of the year 17 (= July / August 638), when ʿUmar came to Mecca for the ʿUmra and spent 20 nights there.

As the number of visitors to the Holy Mosque continued to increase in the following years, the caliph ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān (r. 644–656) had their court expanded again. According to at-Tabarī, this took place in the year 26 of the Hijra (= 646 AD). Those who did not want to give up their houses and protested against the expropriation had ʿUthmān thrown into prison. At the intercession of the governor ʿAbdallāh ibn Chālid ibn Usaid, however, they were released again. Al-Azraqī quotes his grandfather as saying that the Holy Mosque at the time of ʿUthmān consisted only of a curtain wall without a roof. The people, he is supposed to have said, sat around the mosque in the early morning and in the evening and followed the shadow. When the shadow shortened, one rose.

ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair , who ruled from Mecca as caliph from 683 to 692, expanded the mosque on the eastern, northern and southern sides, for which he again bought the nearest houses. In a southerly direction he extended it to the wadi at as-Safā. The houses that were torn down included the house of the al-Azraq family, from whom the historian al-Azraqī was descended from. It bumped into the mosque and opened towards the gate of the Banū Shaiba. Anyone entering the Holy Mosque would have it on their left. ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair bought it from the family for more than 10,000 dinars . On the north side, ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair extended the wall behind the Dār an-Nadwa , so that it was now inside the mosque and its door opened towards the cream . It is possible that ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair already built a simple roof over the mosque. As al-Azraqī reports, this belonged to his grandfather. The mosque was now so spacious that some people could sleep in it. However, it was smaller than Kufa's . Zādān Farrūch, who kept the land register for al-Hajjaj ibn Yūsuf , is quoted as saying: "The mosque of Kufa has nine jaribs , that of Mecca only a little more than seven."

The Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik , who ruled Mecca from 692, had the wall of the mosque raised and covered with a teak roof . His son al-Walīd (r. 705–715) tore down what his father had built after al-Azraqī and rebuilt the mosque, equipping it with marble columns for the first time. He had the building clad with marble slabs, covered with a roof made of decorated teak and equipped with battlements . The capitals of the columns were covered with gold plates and the areas above the column arches were decorated with mosaics .

The building of al-Mansūr: extension on the west and north sides, addition of minarets

The Abbasid caliph al-Mansūr (r. 754-774) had the mosque expanded on the north and west sides and provided with minarets for the first time . The west side was laid out in such a way that it reached from the Banū-Jumah-Gate to the Banū-Sahm-Gate, where the one minaret was erected. The north side was designed as a single-row arcade , which led past the house of Zubaida, the Dār al-ʿAdjala and the Dār an-Nadwa and extended to the house of Schaiba ibn ʿUthmān, where another minaret was built. This north side was decorated with mosaics because it served as the front of the mosque. This north side was then laterally connected to the east side of the building from al-Walīd. The expansion doubled the size of the mosque. The construction work lasted from the Muharram of the year 137 (= July 754) to the Dhū l-Hiddscha 140 (= April / May 758).

The building of al-Mahdī: expansion on the east and south sides, construction of three-row arcades

Al-Mansūr's son al-Mahdī (ruled 775–785) came at the beginning of his reign to make a pilgrimage to Mecca and had the mosque extended to the east. He gave the order for this to the Qādī of Mecca Muhammad al-Machzūmī, nicknamed al-Auqas. He had the houses adjoining the mosque bought and demolished and placed the Masʿā further east. He also had three-row arcades with marble columns built on the east and west sides . The marble blocks required for this were transported by ship from Syria and Egypt to Jeddah and from there on wagons to Mecca. On both sides, grid-like foundations were laid out of walls, the spaces between which were filled with mortar, ashes and rubble. The columns were then placed on the intersections of the grid. Around 780 al-Mahdī came to Mecca again for an ʿumra . On this occasion he noticed that the Kaaba was not in the center of the mosque. So he gave the order to expand the mosque again, this time in a southerly direction, where the waterway was, over which the flash floods ran off when it rained. To make the expansion possible, he had the waterway moved further south and the houses that stood there demolished. Al-Mahdī also had this side furnished with columns made of marble that were brought from Syria and Egypt. When al-Mahdī died in 785, the building was not quite finished. The construction work was now accelerated, but no longer continued with the same care as before.

The extension of the mosque was now 404 cubits in an east-west direction and 304 cubits in the north-south direction (in the middle) and 278 cubits (at the edges). According to the Meccan historian Taqī ad-Dīn al-Fāsī (died 1429) it was each hand cubit (= 0.4512 m). Accordingly, the dimensions of the mosque were converted into the metric system 182 × 137 or 125 meters. Of the 484 columns that enclosed the mosque in three rows, 103 were on the east side, 105 on the west side, 135 on the north side and 141 on the south side. Each pillar was ten cubits high and three cubits around. Some pillars were a little larger and thicker. The distance between the pillars was six cubits and thirteen inches. A total of 498 arches were stretched across the pillars . 321 pillars had a gilded base . Most of the columns were made of marble, but the 44 columns that al-Hādī had added after al-Mahdī's death were made of simple stone.

The walls of the mosque were 18 to 22½ cubits high on the different sides. There were 272 battlements on its outside . On the inside there were stone benches with arches on the north and south sides. Ibn Battūta (died 1354) reports that he saw an inscription on the top of the wall on the western side that dated the expansion of the mosque by al-Mahdī to the year 167 of the Hijra (= 783/84 AD). Towards the mosque there were 46 arches with 174 battlements on the east side, 46 arches with 147 battlements on the north side, 45 arches with 150 battlements on the south side and 29 arches with 94 battlements on the west side. The roof consisted of an upper and a lower roof. The upper roof was covered with wood from the Yemeni gut tree, the lower roof was made of beautiful teak, was decorated with gold and inscribed with verses from the Koran, blessings for the prophet and supplications for the caliph al-Mahdī. There was a gap of two and a half cubits between the two roofs. The building had a total of 24 gates (see the overview below). Al-Mahdī also provided the mosque with two further minarets, which he erected at the other corners of the building and equipped with battlements.

The layout of the two outer courtyards

The caliph al-Muʿtadid bi-Llāh (ruled 892-902) had the Dār an-Nadwa , the old town hall of Mecca, on the north side of the mosque , torn down and the mosque extended in this direction. The new building, which was erected on the site of the Dār an-Nadwa, was equipped with the same columns, arches and halls as the mosque. To connect this extension (ziyāda) with the rest of the mosque, six new gates were broken on its outer wall. In 918, Muhammad ibn Mūsā, the governor of the caliph al-Muqtadir (r. 908-932), had the wall between the extension and the mosque courtyard torn down and replaced with stone pillars, so that now all who are in the “Dār-an -Nadwa Extension ” (Ziyādat Dār an-Nadwa) who could see the Kaaba. He also provided the extension with its own minaret. As an outer courtyard, the Dār-an-Nadwa extension became an integral part of the Holy Mosque.

In 918, Muhammad ibn Mūsā also had the gate of the grain traders and the gate of the Banū Jumah demolished on the west side of the mosque and set up a colonnade-lined mosque courtyard behind it, which he connected with the great mosque. On the outside of this mosque yard, which was 57 cubits long and 52 cubits wide, he built a new gate called the Ibrahim Gate. The namesake was not Abraham , but a tailor named Ibrāhīm, who had his seat long in front of the gate. The pillars in this western extension were made of plaster.

The fire of 1400 and the repairs that followed

On the night of the 28th Schauwāl 802 (= June 22nd, 1400) a fire broke out in the mosque, in which about a third of the building was destroyed. The trigger for this was that a resident of Ribāt Ramuscht, who was lying on the west side of the Hazwara gate and adjoined the mosque, left a burning light in his cell. A mouse, it was said, had pulled this lamp towards its hole, causing the cell to catch fire. The flames soon burst out of the window and set the roof of the mosque on fire. Since people could not reach up that far because of the height of the building and could not extinguish the fire, the fire spread over the entire west side and soon reached the north side as well. There it reached the ʿAdjala Gate, where a fortunate coincidence prevented it from spreading further: a flood that occurred at the beginning of the same year knocked down two pillars there, causing the roof above to collapse had been brought. This vacant lot stopped the fire and saved the rest of the building from destruction. A total of 131 columns melted into lime in the fire , and the rubble was so high that the Kaaba could no longer be seen behind it. The Meccans viewed the conflagration as a warning omen for a great event that occurred shortly afterwards, namely the bloodshed that Timur caused on the Muslim civilian population there during his campaigns through Syria and Anatolia .

The Egyptian Sultan Faraj (r. 1399–1405) commissioned the leader of the Egyptian pilgrim caravan, Baisaq az-Zāhirī, to clean and rebuild the mosque. That is why he stayed in Mecca after the Hajj in 803, which fell on July 1401. He first cleaned the mosque of rubble and then made new columns from granite , which he had broken on the Schubaika mountain near Mecca. He equipped the west side of the mosque with these columns, each with a marble capital. He built the columns on the north side from pieces of white marble, which he connected with iron bolts . At the end of Shabān 804 (= March 1402), Baisaq was able to complete the repairs; Only the repair of the roof he had to postpone because of the lack of suitable timber. In 807 (1404/05 AD) he returned to Mecca to repair the roof. For this he brought suitable timber from Asia Minor. He also had juniper wood brought in from the area of at-Tā'if . With these timbers he was able to complete the repair of the roof on the west and north sides.

The new Ottoman building with the domed roof

Major structural changes to the mosque did not take place again until the Ottoman sultans in the 16th century. In the 1570s, Sultan Selim II (r. 1566–1574) had a large part of the arcades of the Holy Mosque rebuilt. The reason for this was that the arcades on the east side of the mosque courtyard had sunk more and more, the roof on the other sides was rotten and eaten away by woodworms (araḍa) and, moreover, birds and snakes nested in the space between the upper and lower roof had. As the contemporary historian Qutb ad-Dīn an-Nahrawālī (died 1590) reports, Selīm II gave the order to the Hijra (= 1571/72 AD) in 979 to open the entire mosque from all four sides “to the best and most beautiful way ” (ʿalā aḥsan waǧh wa-aǧmal ṣūra) , whereby firmly bricked domes should be put in place of the double wooden roof . The Ottoman builder Amīr Ahmad Beg, who had previously carried out the final work for the ʿAin ʿArafāt water pipe in Mecca, was commissioned to manage the construction .

In the middle of Rabīʿ I 980 (end of July 1572) Ahmad Beg tackled the renovation of the arcades and began the demolition work. First he exposed the entire east side and examined the foundation. When he found it damaged, he had the foundation walls in the earth, which had the shape of a chessboard, completely removed. On the 6th Jumādā I 980 (September 14, 1572) the laying of the foundation stone of the new building was celebrated in the presence of the great personalities of Mecca. Since it became apparent that the earlier pillars were not strong enough to support the domes, he had pillars made of yellow local Shumaisī stone, four times as thick as the marble pillars, inserted between the white marble pillars. The Shumaisī stone was broken on two small mountains near Shumais on the western border of the Haram on the way to Jeddah . Ahmad Beg had a pillar made of Shumaisī stone follow every third marble column. As a result, enough marble was now available to adapt the western colonnade, which had been filled with granite columns after the fire of 1400, to match the other colonnades and also to provide them with marble columns again.

The new construction of the mosque was only under the rule of Murād III. Completed in 984 (1576/77 AD). So that the pigeons could not sit on the arcades and pollute the mosque with their excrement, their cornices were shod with iron spikes all around . In addition, gilded crescent moons made of copper, which were made in Egypt on behalf of the local Beglerbeg Mesīh Pasha, were attached to the domes . Finally, in 985 (1577/78 AD) between the ʿAlī gate and the gate of the funeral procession an inscription with the names of Allah , Muhammad and the four rightly guided caliphs was placed. A total of 110,000 new gold dinars from the sultan's treasure were spent on the new building, including the canal systems to ward off floods (see below) . This did not include the cost of the lumber sent from Egypt to Mecca, the wooden poles for the building tools, the nails, the iron spikes, and the gilded crescent moons on the domes.

The renovation fundamentally changed the appearance of the central building complex in Mecca. In total, the building now had 152 domes and 232 "pans" (ṭawāǧin) . According to the Ottoman scholar Eyüb Sabri, the "pans" were also a type of domes, which were so named because of their shape. Qutb al-Dīn an-Nahrawālī praises the beauty of the new domes in his chronicle. In his opinion, they looked like the gold-decorated Üskuf hats of janissary officers who stand around the church in a closed row and with the utmost discipline and calm. The pillars in the four halls were also completely rearranged. In total, the new building had 311 marble columns and 244 pillars made of yellow Shumaisī stone.

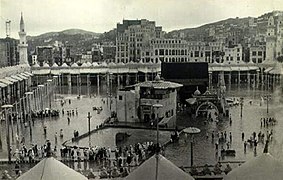

Excursus: Pictorial Representations in Islamic and Western Art

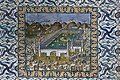

After the Ottoman renovation, the Holy Mosque became a very popular motif in Islamic art. In particular, many Ottoman tiles are designed with representations of the building complex. Such tiles are usually referred to as "Kaaba tiles" in the history of oriental art, but the representation is usually not limited to the Kaaba alone, but includes the entire Holy Mosque. In addition, several works were created on the holy places in Mecca and Medina, which were illustrated with depictions of the Holy Mosque. This included in particular the book Futūḥ al-ḥaramain by Muhyī ad-Dīn Lārī (died between 1521 and 1527), of which there are numerous illustrated manuscripts from Turkey, Iran and India. Various Ottoman buildings are also decorated with depictions of the Holy Mosque. Many of these representations are labeled in Arabic with the names of the gates and buildings in the inner courtyard, so that they could also be used to explain the local conditions on site. In addition, the motif of the Holy Mosque is often found on Turkish prayer rugs from the city of Bursa . The mosque is shown from the east on almost all of the depictions.

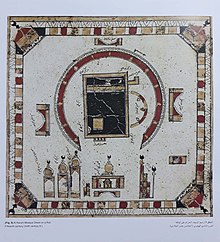

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the mosque was usually shown in a combination of floor plan and elevation , in such a way that the inner courtyard of the mosque was shown from above, while the arcades and the individual structures that stood in this courtyard were folded down were shown in side view. Well-known representations of this type can be found on various tiles from İznik , on two Futūḥ-al-ḥaramain manuscripts from Uzbekistan and India, and on one in the mihrāb of the mosque of the Black Eunuchs in the Topkapı Palace . The representation in the Topkapı Palace consists of a group of individual tiles and fills the semicircular back wall of the mihrāb. The minarets are shown on it disproportionately long. A very similar panel made of tiles , but flat, is in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo . It is dated to the year 1676 and has an area of 2.40 × 1.44 meters. With some early Ottoman representatives of this type of representation, a third type of representation is added because the Kaaba, the arcades and individual other parts of the building are depicted in perspective. This is the case with the images of the Holy Mosque in the Cevahirü'l-Garâib manuscript from 1582 in the Harvard Art Museums and in the Manāsik work by Bahtî from 1646 in the Berlin State Library .

- Representations that combine floor plan and elevation

İznik tile in the Victoria and Albert Museum , 1666

Mihrab in Topkapı Palace , 17th century

Ottoman Manāsik factory in Berlin, 1646

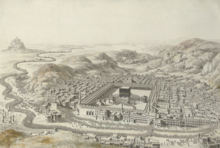

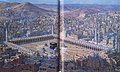

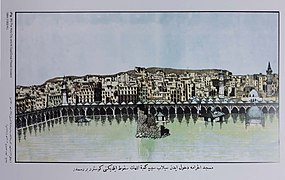

In the early 18th century, depictions of the Holy Mosque from a bird's eye view in oblique parallel projection became more common in the Ottoman Empire . In these representations, the mosque is usually surrounded by other stations of the pilgrimage and the mountains of Mecca, which are inscribed with their names. One of the earliest representations of this kind can be found in an Ottoman collective manuscript from 1709, which is kept in the Berlin State Library. An oil painting on canvas, acquired by the Swedish orientalist Michael Eneman during a stay in Turkey and bought by the library of Uppsala University in 1717, dates from around the same time . It depicts the mosque in a very realistic way. Other well-known depictions depicting the mosque in this way are a tile made in Tekfur Sarayı from 1720–30 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art , a tile panel made at the same location from around 1735 in the Hekimoğlu Ali Paşa Mosque in Istanbul, the interior painting of the lid of a Qibla indicator from 1738 in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul and a panel consisting of twelve tiles in Sabīl-Kuttāb by ʿAbd ar-Rahmān Katchudā in 1744 the al-Mu'izz street in Cairo. The depiction of the Holy Mosque on a copper engraving in the architecture book by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach , which was published in 1721, also follows this pattern, but in contrast to the Ottoman depictions, it is a depiction in vanishing point perspective .

- Illustrations from a bird's eye view

Tile from Tekfur Sarayı , 1720–30

Tiles in the Sabīl-Kuttāb of Katchudā in Cairo, 1744

Blueprint of a historical architecture , Fischer von Erlach , 1721

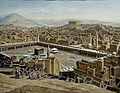

In the 19th century, depictions of the Holy Mosque embedded in the urban ensemble down from the mountain became more common. To some extent, this type of representation can already be found in the Ottoman oil painting from Uppsala and the drawing by Louis Nicolas de Lespinasse (see above), which is dated to 1787 and probably also had an Ottoman model. This type of representation can be found in full development in the panorama-like picture that the Indian painter Muhammad ʿAbdallāh, a grandson of the court painter of Bahadur Shah II , made in Delhi for one of the sheriffs of Mecca . Some of these representations also have photographic originals such as the one by Hubert Sattler from 1897, which is based on a photograph that Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje published in 1889. The French orientalist painter Etienne Nasreddine Dinet (1861–1929) made a similar view in 1918 .

- Panoramic representations down from the mountain

Oil painting by Hubert Sattler , 1897 ...

... and a photographic copy by Snouck Hurgronje , 1889

Extensions under Saudi rule

At the beginning of the Saudi rule, the inner courtyard of the al-Haram mosque was roughly in the shape of a parallelogram . The individual sides had the following dimensions: 164 meters (north side), 166 meters (south side), 108 meters (east side) and 109 meters (west side). The total area of the mosque was 17,902 square meters. From the outside it was about 192 meters long and 132 meters wide.

In the early 1950s, the Saudi King ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Saʿūd commissioned the entrepreneur Muhammad ibn Lādin , who had previously directed the expansion of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina, to plan a comprehensive expansion of the al-Harām mosque. Muhammad ibn Lādin, for his part, commissioned the civil engineer Fahmī Muʾmin, who had designed the mosque in Medina, to work out a design. Some time later he submitted the design for a new rotunda, which, however, was not approved by the king and his advisors. Thereupon Muhammad ibn Lādin commissioned the Egyptian civil engineer Muhammad Tāhir al-Dschuwainī with the elaboration of an alternative design, which provided a rectangular building. As the number of pilgrims rose to more than 200,000 in the mid-1950s, while the mosque could only accommodate around 50,000 prayers, the need to expand the building became more and more noticeable.

First expansion (1955–1969)

After the planning work was completed, King Saʿūd ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (r. 1953–1964) publicly announced his will to expand the al-Haram mosque on August 22, 1955. As the project made it necessary to demolish buildings in the area, the king set up a commission to assess the value of these buildings. The owners of the buildings were compensated according to their assessment. In September 1955 he set up a commission to oversee the construction project. It was placed under the direction of the then heir to the throne Faisal ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz . Construction work began on November 20, 1955 with the demolition of the two outer courtyards, the houses connected to them and the buildings and shops in the vicinity of the mosque. In March 1956, Muhammad ibn Lādin was commissioned to carry out the construction project. The ceremonial laying of the foundation stone took place on 23rd Schaʿbān 1375 (= 5th April 1956).

This officially began the project known as the “First Saudi Enlargement”. This comprised two phases:

- During the first phase (1957 to 1961) the Masʿā, i.e. the ritual running route between as-Safā and al-Marwa, was expanded into two floors. In addition, a dome was built over as-Safā and a new higher minaret next to it.

- During the second phase (1961 to 1969) the mosque was given a second floor and a basement and was connected to the Masʿā. In addition, the buildings in the courtyard of the mosque were (see below) demolished to the surface for the circulation around the Kaaba to increase, and the Zamzam was moved to the ground.

Overall, the area of the mosque was increased to 161,327 square meters through the expansion. A large part of the newly created areas was accounted for by the masʿā, which was considered an integral part of the mosque after the expansion, as well as the cellars built under the arcades. The mosque building could now accommodate a total of 400,000 prayers. The total cost of expanding the mosque during King Saud's reign was one billion Saudi riyals . This amount also included nearly 240 million riyals, which were paid as compensation to the owners of the 1,700 buildings, apartments and businesses that were demolished in the course of the mosque's expansion.

Second expansion (1969–1976)

Under King Faisal ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (ruled 1964–75) the second Saudi expansion of the mosque began. The blueprint of the architect Muhammad Tāhir al-Juwainī actually intended that the old mosque should be completely removed. In 1968/69, however, Faisal changed this plan by decreeing in a royal order that the arcade courtyards from Ottoman times with the domed roof should be preserved, repaired and connected to the new building. The second Saudi enlargement will also be divided into two phases:

- During the first phase (1969 to 1972) the exterior of the mosque was redesigned and a ramp was built at the Safā gate that connects the mosque's ground floor with the Masʿā. In addition, the floor of the mosque was paved with marble slabs, and two new minarets were built on the northwest side by the ʿUmra Gate.

- During the second phase (1973 to 1976) the old building of the mosque with the domed arcade courtyards from the Ottoman period was restored and the north side of the mosque was redesigned. Two new minarets were built on the northeast corner, and two new gates were built on the northwest and northeast sides.

The two outer courtyards of the old mosque building were removed as part of this expansion. In order to improve the flow of traffic and make it easier for pilgrims to access the mosque during peak hours, five spacious spaces with parking spaces were created around the building. The new mosque building comprised almost 70 new prayer rooms and at the end of the second expansion could accommodate a total of more than 600,000 prayers.

Third expansion (1988–1993)

A third expansion of the mosque took place during the reign of King Fahd ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz (r. 1982-2005). The solemn laying of the foundation stone for this extension, named after King Fahd, took place on September 13, 1988. In the course of this extension, which again required the demolition of numerous buildings, a new annex was built on the western side of the mosque, with its own Main entrance and two minarets received. It has two floors and a basement. The outer walls have a uniform height of 22.57 meters. Inside there are 492 columns with a diameter of 81 and 93 centimeters. Three domes 15 meters in diameter and seven meters high were erected on the roof of the new extension. They tower over the central hall of the new building.

In order to improve the use of space in the building, the roof of the mosque and the new annex were made accessible, covered with marble and designed into a contiguous prayer area of 61,000 square meters, which was later covered with prayer rugs. Overall, the prayer area of the mosque was increased to approx. 400,000 square meters and the capacity of the building was increased to more than a million people.

Inside, the mosque building was equipped with 13 escalators , a network of fire protection stations and a modern central air conditioning system. The air conditioning system is supplied with district cooling , which is brought in via an underground pipeline from a refrigeration machine six kilometers away . Numerous water dispensers have also been set up in the mosque , from which visitors to the mosque can draw chilled Zamzam water.

In 1990, on royal orders, a program began to beautify the squares around the mosque, with the aim of making them usable for prayer during rush hours during pilgrimages and Ramadan . A new two-story building with sanitary facilities was built on the square west of the Masʿā, comprising 1,440 toilets and 1,091 places for ritual washing. The square in front of the mosque to the south-west was also provided with underground sanitary facilities and freed from traffic by building a 661-meter-long tunnel. This Sūq-as-Saghīr tunnel connects the area of the Holy Mosque with the eastern quarters of Mecca. In order to reduce traffic in the mosque area, a park-and-ride system with large parking lots in the districts of Kudai and al-ʿAzīzīya, which have around 12,000 parking spaces, was established. From there, pilgrims can get to the mosque in ten to 20 minutes by bus. In May / June 1993 work on the third extension of the mosque was completed.

Fourth expansion (from 2007)

The fourth expansion of the mosque began in 2007 during the reign of King Abdullah ibn Abd al-Aziz (ruled 2005–2015). In order to allow the building complex to expand in a northerly direction, the district of asch-Shāmīya was demolished in 2008. A total of 5,882 buildings were demolished over an area of 300,000 square meters. For the planning of the extension, the Saudi government commissioned 18 international architects and architectural offices, including Zaha Hadid , Tadao Andō , Norman Foster , Santiago Calatrava , Shigeru Ban and Atkins Design , to develop drafts. Most architects could only find out about the site through photos and satellite images, since as non-Muslims they were not allowed to enter Mecca. The designs were presented to the King of Saudi Arabia at the end of November 2008. In the end, a draft from King Saud University prevailed . The designs of the other architectural firms were published in a book by the Saudi Ministry of Culture and Media in 2012.

After the completion of the construction work, which was originally planned for 2020, the building should offer space for 2,000,000 believers. Furthermore, the number of minarets is to increase to 13. The cost of the project is 80 billion Saudi riyals (approx. 20 billion euros). The expansion was justified, among other things, by the fact that by 2025 an increase in the number of pilgrims to up to 17 million annually is expected. Simultaneously with the start of the expansion of the Holy Mosque, the high-rise towers of Abraj Al Bait , which are up to 601 meters high, were built in the immediate vicinity . They now tower above the Holy Mosque, which has fundamentally changed its appearance. The construction management for both projects lies with the Saudi Binladin Group . Workers from various Islamic countries work on the construction sites. Most of them live in very confined conditions on the Saudi Binladin Group's premises.

The expansion project has met with a lot of criticism in the meantime. Hatoon al-Fassi , a professor of history at King Saud University who comes from a respected Meccan family, accused the Bin Ladin Group of wanting to turn Mecca into a Las Vegas . Ziauddin Sardar criticized the “brutalism of hideously ugly right-angled steel and concrete structures” that now surround the Holy Mosque. They would look like downtown office complexes in some US city. It was also criticized that the remaining Ottoman portico should be removed. After protests from the Turkish side in 2013 and subsequent Turkish-Saudi negotiations, the Saudi king finally gave the order to preserve the portico and commissioned the Turkish company Gürsoy Group to investigate and restore it. The company removed the pillar porch in 2015, restored it on a site near ʿArafāt and partially rebuilt it at a greater distance from the Kaaba. However, the original Ottoman brick and stucco domes could not be preserved. The renovation significantly increased the capacity of the inner mosque courtyard. While before 2013 only about 10,000 people per hour could do the tawāf per hour, this has been possible for 30,000 people since the renovation.

In order to maintain the capacity of the mosque during the renovation period and to enable as many people as possible to circulate around the Kaaba at the same time during the Hajj, a temporary matāf bridge made of carbon fibers was erected in the courtyard of the mosque between 2014 and 2016 . On September 11, 2015, one hour before the evening prayer and about ten days before the start of the Hajj, a large crawler crane with articulated boom ( Liebherr LR 11350 ) fell backwards onto the mosque in heavy rain and gusts of wind at speeds of up to 83 km / h and hit the mosque with it a hall roof on the third floor for the guy arms. The top of the mast buckled into the courtyard beyond. At least 107 people were killed and 238 injured.

History of individual components and the infrastructure

The goals

Almost all Meccan historians provide lists of the gates of the Holy Mosque in their works, including al-Azraqī (early 9th century), Taqī ad-Dīn al-Fāsī (early 15th century) and the modern historian Husain Bā-Salāma, the describes the situation in the early 20th century and evaluates the earlier literature. As can be seen from their lists, the number of gates decreased from 24 in the 9th century to 19 in the 15th century and finally increased again to 26 in the early 20th century. The names of the individual gates have also changed several times over the years. In the 9th century, many of the gates were named after the Quraishite clans who lived around the Kaaba in pre- and early Islamic times (e.g. Banū Schaiba, Banū Sahm, Banū Machzūm, Banū Jumah). In later times these tribal names were replaced by other names.

The individual gates were of different sizes: some had multiple arches, others only one. The Al-Safa gate through which the pilgrims usually left the mosque when they after Tawaf for Mas'ā went, was with five arches, the largest gateway. In the 15th century, the mosque had a total of 35 archways. In each archway there was a door with two door leaves . Several gates were also provided with a slip gate . It stayed open when the gate was closed at night.

Since the mosque was about three meters lower than its surroundings on all sides, most of the gates were provided with steps that led down to the mosque. The number of steps for the individual gates varied between nine and 15. However, the surface shape of the mosque had been basin-like since the late Middle Ages: the edges of the mosque were also raised compared to the outside environment. So if you wanted to enter the mosque, you first climbed a few steps up and then down several steps again. This basin-like edge of the mosque was laid out in 1426/27 and served to protect against flooding (see below).

As can be seen from Ibn Jubair's travelogue , it was the rule in the 12th century that pilgrims who came to the ʿUmra in Mecca entered the mosque through the Banū-Shaiba gate, circulated seven times and then through the as-Safā Gate. It later became common for ʿUmra pilgrims to enter the mosque through the Banū Sahm Gate. That is why this gate was called ʿUmra Gate from the 14th century.

|

al-Azraqī (d. 837) |

Taqī ad-Dīn al-Fāsī (d. 1429) |

Husain Bā-Salāma (d. 1940) |

Number of archways |

Remarks | picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East side (from north to south) | |||||

| 1. Banu Shaiba Gate | 1. Salam Gate | 1. Salam Gate | 3 | According to al-Azraqī, the gate was called Banū-ʿAbd-Shams- Gate in pre- and early Islamic times . At the beginning of the 10th century the front was decorated with a mosaic. Ibn Battūta writes that the caliphs used to enter the mosque through this gate. It is not clear why the gate was later called the Salām Gate (Bāb as-Salām) . At the beginning of the 20th century, pilgrims entered through this gate when they wanted to complete the arrival circuit (ṭawāf al-qudūm) . | |

| 2. Dār-al-Qawārīr Gate | 2. Gate of the Qā'itbāy Madrasa | 1 | The Dār-al-Qawārīr ("House of Crystal Glasses"), after which the gate is named, was a palace originally built for himself by the Barmakid Jafar ibn Yahyā. It was later confiscated by the Meccan governor Hammād al-Barbarī, who rebuilt it for Hārūn ar-Raschīd and equipped it with crystal glasses (qawārīr) inside . Around 1480 the Madrasat al-Ashraf Qā'itbāy was built there. Early 20th century the gate consisted only of a small hatch. | ||

| 3. Prophet's Gate | 2. Gate of the funeral procession | 3. Prophet's Gate | 1/2 | The name “Prophet's Gate” (Bāb an-Nabī) comes from the fact that Mohammed is said to have used it when he went from his house to the mosque. The later name “gate of the funeral procession” (Bāb al-Ǧanāʾiz) is explained by the fact that the funeral procession left the mosque through this gate or was carried through this gate into the mosque so that the funeral prayer could be said about them. The gate was enlarged from one to two arches in the Middle Ages. | |

| 4. al-ʿAbbās gate | 3. al-ʿAbbās gate | 4. al-ʿAbbās gate | 3 | The name of the gate came from the fact that al-ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-Muttalib had his house nearby. The fronts and interiors of the three arches were decorated with mosaics in the early 10th century, and the walls were made of white, green, and red marble, as well as gold-plated marble. | |

| 5. Banū-Hashim Gate | 4. ʿAlī gate | 5. ʿAlī Gate | 3 |

|

|

| South side (from east to west) | |||||

| 1. Banū ʿĀ'idh Gate | 1. Bāzān Gate | 1. Gate of the bier | 2 | The name Bāzān-Tor was derived from the fact that the water basin stood here, which was supplied with water by the ʿAin Bāzān . The later name “gate of the bier” (Bāb an-Nuʿūš) comes from the fact that the bier was carried out through this gate to the Jannat al-Muʿallā . | |

| 2. Banu Sufyan Gate | 2. Baghla Gate | 2. Baghla Gate | 2 | It was named after the Banū Sufyān ibn ʿAbd al-Asad. | |

| 3. as-Safā gate | 3. as-Safā gate | 3. as-Safā gate | 5 | The gate was directly at as-Safā and was the largest gate of the mosque. After al-Azraqī, the gate was also called Banū-Machzūm-Tor, after the Quraishite clan of Banū Machzūm, who lived at the gate, or Banū-ʿAdī-ibn-Kaʿb-Tor. The front and the inside of the arches were decorated with mosaics at the beginning of the 10th century, the two pillars of the middle arch were provided with gold-colored inscriptions. The walls of the gate were made of gold-plated marble as well as white, green, and red lapis lazuli-colored marble. |

|

| 4. Banū Machzūm Gate I | 4. Small Ajyad Gate | 4. Small Ajyad Gate | 2 | ||

| 5. Banū Machzūm Gate II | 5. Mujāhidīya gate | 5. Ajyad Gate | 2 | In the time of al-Fāsī, it was also called the Gate of Mercy (Bāb ar-Raḥma) . The name Mujāhidīya comes from the fact that a madrasa was founded here by the Rasulid ruler Mujāhid (r. 1322-1363). |

|

| 6. Banū Machzūm Gate III | 6. Gate of the Adschlan Madrasa | 6. Gate of the Adschlan Madrasa | 2 | In the time of al-Azraqī it was also called the Banū Taim Gate. Later the madrasa of the Sherif ʿAdschlān ibn Rumaitha (r. 1361-1375) gave the name. In the early 17th century it was called the Sherif Gate ( Bāb aš-šarīf ) because the house of the Sherif Surūr was across from it . In the early 20th century, the gate was named after the Egyptian hospice ( Takīya Miṣrīya ) in front of it, also Takīya-Tor. | |

| 7. Umm Hānī Gate | 7. Umm Hānī Gate | 7. Umm Hānī Gate | 2 | It was named after Umm Hānī, a daughter of Abū Tālib ibn ʿAbd al-Muttalib . It was also called the Malāʿiba Gate in the time of al-Fāsī. In the sixteenth century, this is the gate used by Mecca to enter the mosque. In the early 20th century, the gate was also called Hamīdīya Gate, after the Hamīdīya, the seat of the provincial government, which was located here. |

|

| West side (from south to north) | |||||

| 1. Hizāmīya Gate | 1. Hazwara Gate | 1. Farewell gate | 2 | In the time of al-Azraqī, it was also called the Banū-Hakīm-ibn-Hizām Gate or Banū-Zubair Gate. Hazwara was the former market of Mecca. It later became customary for pilgrims to exit the mosque through this gate when they were leaving. Hence the name "Farewell Gate " (Bāb al-Widāʿ) | |

| 2. Grain Merchants Gate (Bāb al-ḥannāṭīn) | 3 | Was demolished in 914 during the expansion of the mosque. | |||

| 2. Ibrāhīm Gate | 2. Ibrāhīm Gate | 1 | The Ibrāhīm Gate, which had a very large arch, was only built in 914 when the mosque was being expanded. It was named after a tailor Ibrāhīm who sat here before it was built. | ||

| 3. Banu Jumah Gate | 2 | The gate had been built by the caliph al-Mansūr, who had a mosaic attached to the front. In 914 it was demolished when the western outer courtyard was being built. | |||

| 3. Nameless Gate | 1 | On the northern side of the Ibrāhīm extension | |||

| 4. Abū-l-Buchturī Gate | 4. Gate of the Ghālib Madrasa | 1/2 | The gate was extended to two archways. | ||

| 5. Nameless Gate | 5. Gate of the Dāwūdīya Madrasa | 1 | |||

| 6. Banū Sahm Gate | 3. ʿUmra Gate | 6. ʿUmra Gate | 1 | This gate was usually from the umra , used -Pilgern, who went out to Tan'im when entering and leaving the mosque. | |

| North side (from west to east) | |||||

| 1. Gate of ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀs | 1. Sudda Gate | 1. al-ʿAtīq Gate | 1 | Named after a notable named Ibn ʿAtīq who lived here. | |

| 2. Nameless gate, locked |

2. Gate of the Zimāmīya madrasa | 1 | |||

| 3. Dār-al-ʿAdjala Gate | 2. Dār-al-ʿAdjala Gate | 3. Bāsitīya Gate | 1 | The Dār al-ʿAdschala, after which the gate was first named, was a palace that ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair had built on this site. The later name Bāsitīya goes back to a madrasa that stood here and was donated by ʿAbd al-Bāsit, an officer of the Mamluk Sultan al- Ashraf Barsbay (r. 1422-38). | |

| 4. Quʿaiqiʿān Gate | 1 | It was also called the Hudjair-ibn-Abī-Ihāb-Tor. In 894 it was demolished in the course of the expansion of the mosque. | |||

| 3rd nameless gate | 4. Qutbi Gate | 1 | On the western side of the Dār-an-Nadwa extension, which was only built in 894. The name Qutbī-Tor is derived from the fact that it was located near the madrasa ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Qutbīs, the nephew of Qutb ad-Dīn an-Nahrawālī . | ||

| 5. Gate of Dār an-Nadwa | Was demolished in 894 during the expansion of the mosque. | ||||

| 4. nameless gate | 5. Ziyāda Gate | 2/3 | On the western side of the Dār-an-Nadwa, which was only built in 894 mosque. The gate was expanded from two to three arches in the 16th century. In the 16th century it was known as the Suwaiqa Gate. | ||

| 6. Gate of the Shaiba ibn ʿUthmān | 1 | Was demolished in 894 during the expansion of the mosque. | |||

| 6. Court Gate | 1 | Was created during the construction of the Madāris Sulaimānīya . Since one of the schools later became the seat of the court, it was called the court gate (Bāb al-Maḥkama) . | |||

| 7. Sulaimānīya Gate | 1 | Around the middle of the 20th century it was also called the Library Gate ( Bāb al-Kutubḫana ) because it was used to get into the library of the Holy Mosque. | |||

| 5. Duraiba Gate | 8. Duraiba Gate | 1 | So called because through this gate a small path ( darb ) led to Suwaiqa. | ||

During the first Saudi expansion, the old gates of the mosque were torn down and new main gates were erected at three corners, each with three entrances, the King ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Gate in the southwest, the dasUmra Gate in the northwest and the Salām Gate in the northeast ( today Fath Gate). The individual entrances are 5.38 meters high and 3.10 meters wide. Each main gate is preceded by a large vestibule, which is followed by a wide passage through which one can get into the interior of the mosque. In addition to these main gates, numerous smaller gates were built, so that the number of gates of the mosque after the first expansion was 61. Some of the old gate names have been retained. As the fourth main gate in the style of the existing gates, the King Fahd Gate was added to the new extension on the western side during the third expansion.

The minarets

The first two minarets of the al-Haram mosque were built at the end of the 8th century by the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur on the north side of the mosque. While the minaret in the northeast corner was demolished during the expansion of his son al-Mahdī, the minaret in the northwest corner at the Banū-Sahm gate remained. Under al-Mahdī, the mosque received three more minarets, which were erected at the other three corners of the building and equipped with battlements . The southeastern minaret was called the Meccans Minaret . For a long time, an ascetic named Abū l-Hajjāj al-Churāsānī lived on the northeastern minaret and prayed there day and night. He only came down on Fridays to attend Friday prayers . In 918, Muhammad ibn Mūsā had a fifth minaret built on the outer courtyard of the Dār-an-Nadwa extension.

Jamāl ad-Dīn al-Isfahānī (died 1164), the vizier of ʿImād ad-Dīn Zengi , had the minaret built by al-Mansūr over the Banū-Sahm- Renew gate. Ibn Jubair , who visited the mosque in the late 12th century, describes that in his time it had seven minarets, four in the four corners, two in the outer courtyards and another small one above the as-Safā gate, which indicated its location , but could not be climbed because of its narrowness. The individual minarets were designed individually, but the lower half consisted of a square base made of finely hewn stones and the upper half of a column made of fired bricks. In the middle and at the top there were two finely crafted wooden balustrades.

The two minarets above the Ibrāhīm gate and the as-Safā gate were later demolished, so that the mosque only had five minarets in the 14th century. The minaret above the Hazwara Gate in the southwest corner collapsed in 1369 without harming people. Al-Ashraf Shabān , Sultan of the Mamluks in Egypt from 1363 to 1377, had it rebuilt the following year. In February 1407, the minaret above the Banū-Shaiba gate in the southeast corner also collapsed. This time, the repairs were carried out by Sultan Faraj ibn Barqūq . It could be completed by April 1409. A new sixth minaret was built by Sunqur al-Jamālī over the Madrasat al-Ashraf Qā'itbāy around 1480 . In May 1504 it was partially destroyed by a lightning strike in a storm, but it was restored in the same year.

In 1524/25 the Ottoman Sultan Suleyman I had the two minarets in the north-west and south-east corners, which were built in the style of the Egyptian minarets, torn down and rebuilt in Ottoman style with a point. A new seventh minaret was built in 1565/66 by the Ottoman builder Qāsim Bey from yellow Shumaisī stone over the Madāris Sulaimānīya . It was also in Ottoman style, had three balconies and was considerably higher than the other minarets. According to their locations, the seven minarets were called 1. Umra Gate Minaret, 2. Salām Gate Minaret, 3. Alī Gate Minaret, 4. Farewell Gate Minaret, 5. Ziyāda Gate Minaret, 6. Sultān-Qā 'itbāy Minaret and 7th Sulaimānīya Minaret. In the early morning, a long series of litanies and praises were usually recited by the muezzins on the minarets. At the end of the morning the call to prayer followed .

During the Saudi expansion of the mosque, the old minarets, which were of different heights, were replaced by seven new minarets in other locations with a height of 95 meters and a uniform appearance. Six of these were put together in pairs at the corners of the mosque, where they flank the three main entrances, the Fath Gate, the ʿUmra Gate and the King ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Gate, the seventh gate being next to the dome of as-Safā built. The minarets were clad with marble slabs on the outside and each have two octagonal balconies, a larger one in the middle and a smaller one at the top, both of which are covered by a canopy with green roof tiles. Inside there are spiral stairs that lead to the balconies. Two more minarets were later built over the King Fahd Gate, increasing their number to nine. Overall, the number of minarets is to be increased to 13 in the course of the expansion currently taking place.

The buildings in the inner courtyard

The central building in the inner courtyard of the mosque was and is the Kaaba with the black stone and the hijr, in which Ishmael's tomb is said to be. In front of the corner with the black stone, the building of the Zamzam fountain was located on an area covered with marble slabs until the middle of the 20th century. This was expanded in 1541/42 by the Ottoman official Emir Hoschgeldi. Since then it has had a second floor with a ceiling made of decorated wood. Above it was a hipped roof with a small dome in the middle.

To the east of the Kaaba were the building of the Maqām Ibrāhīm, the Banū-Shaiba gate and the minbar for the Chutba until the middle of the 20th century . The Banu Shaiba Gate consisted of an arch that rested on two marble pillars. On it the Quranic claim “Enter into them safely and in peace” (Sura 15:46) was appropriate. In addition, pavilions were set up around the Kaaba, where the believers from the four different Sunni schools of law performed in separate prayer groups (see below). In the time of Ibn Jubair these consisted of two wooden pegs each, which were connected to each other like a ladder by rungs and were fixed on plaster plinths that barely rose from the ground. A crossbeam was nailed to the top of this structure, to which iron hooks for the glass lamps were attached. In between there was a prayer niche . At the beginning of the 15th century, the pavilions were expanded and the wooden pegs were replaced by stone pillars. The upper level of the Hanafite pavilion, which was particularly large, served during the Ottoman time also as a stand of the so-called mukabbirūn , the mosque employees who during prayers from an elevated location from the Takbeer so that the praying more distant knew the Imam according repeated, when to continue with their prayer movements.

On the eastern side of the Zamzam building, a qubba-shaped building was built in the fourth century of the hijra (= 10th century AD) , which was used to store equipment. Candles, cushions for the minbar, candlesticks and copies of the Koran were kept here. The building is already mentioned by Ibn Jubair as the "Jewish Qubba", but it is not explained how this name came about. Later this building was called Qubbat al-farrāšīn ("Qubba the carpet -broader "). Behind this qubba another qubba was built in 1404/05, which was called the ʿAbbās potion (siqāyat al-ʿAbbās) . Inside it was a basin that was connected to the Zamzam building by a pipe. The zamzam water was poured into this pipe so that people could drink it in the potion. However, this custom was abandoned in the 17th century. Immediately behind this building was another smaller building, in which devices for lighting and extinguishing the lamps, the monthly lamp oil and additional lamps, which were lit on the maqam on especially holy nights, were kept. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Ottoman master builder Hasan Pascha built a new building near the Baghla Gate to store the lamp oil and the lamp lighters. From then on, the original building for their storage was used for the storage of the Surr, i.e. the donations for the residents of Mecca, for several years. However, this reorganization did not prevail.

During the rule of the Ottoman sultan Abdülmecid I (r. 1839–1861), the ʿAbbās trough was converted into a small library and furnished with valuable books. The other Qubba building was used for timing and star observation. After a flood severely damaged the two Qubba buildings and the items they contained, they were demolished in 1883/84. In this way, more space was created for those praying at the same time. The books of the ʿAbbās potions were moved to the library of the Madāris Sulaimānīya .

The other buildings near the Kaaba were demolished in the middle of the 20th century during the extensive expansion of the mosque under King Saud ibn Abd al-Aziz, as the Matāf, i.e. the place on which the circulation around the Kaaba The Maqāme of the Hanbalites, Malikites and Hanafis were removed in 1957, the building of the Zamzam Fountain, on which the Maqām of the Shafiites was located at that time, in 1963, and the gate of the Banū Shaiba in 1967. The Zamzam fountain was relocated to an air-conditioned basement room under the matāf, which had an area of about 100 square meters, had separate entrances and areas for men and women, and was accessible via a staircase from the eastern part of the mosque courtyard.

As a replacement for the Hanafi maqām, which had also served as a stand for the Mukabbirūn, the Mukabbirīya was built in 1967 on the south side of the mosque as a new rectangular building with two floors. It also served as the starting point for the transmission of the call to prayer and as a broadcasting center for the transmission of radio and television programs from the Holy Mosque to the Islamic world. In order to increase the area for the tawāf again, the entrance to the Zamzam cellar was relocated again in 1979 to the eastern edge of the mosque courtyard. In this way, the area of the Matāf was increased from 3298 to 8500 square meters. The Zamzam basement was expanded at the same time to an area of 1210 square meters so that it could now accommodate 2500 people.

The minbar

After al-Azraqī, Muʿāwiya ibn Sufyān was the first to equip the mosque with a minbar. He is said to have brought this minbar, which had three steps, with him from Syria when he went on a pilgrimage. When Hārūn ar-Raschīd went on a pilgrimage later, his governor in Egypt, Mūsā ibn ʿĪsā, gave him a new, large carved minbar with nine steps, which from then on served as the minbar of Mecca, while the old minbar was brought to ʿArafāt. Later, various Abbasid caliphs had new wooden minbars built for the mosque. However, when in 1077 the vizier al-Muqtadīs sent a new splendid minbar to Mecca, on which was engraved that al-Muqtadī was the "commander of the believers", this was burned in Mecca because the Sherif of Mecca shortly before Assumed Fatimids . Ibn Jubair , who visited the Holy Mosque at the end of the 12th century, describes that the minbar was in front of the Maqām Ibrāhīm and stood on four wheels. Other new wooden minbars were donated by the Mamluk rulers of Egypt in the 14th and 15th centuries. Around the middle of the 15th century, the Chutba was kept on a minbar that al-Mu'aiyad Sheikh had sent to Mecca along with a Kaaba staircase during the Hajj in 1416.

All of these wooden minbars were movable. For the Chutba they were pushed directly against the Kaaba wall between the Black Corner and the Yemeni Corner. After the end of the Chutba, they were pushed back to their place next to the Zamzam well. In 1558/59 Sultan Suleyman then sent a very finely crafted marble minbar to Mecca, which was firmly anchored in the ground. It remained in the mosque courtyard until the middle of the 20th century. In 1963 it was moved seven meters further outwards as part of the expansion of the Matāf. It was dismantled and reassembled at the new location. In 1977 or 1978 he was transferred again when the Matāf was expanded, this time to the area outside the mosque courtyard. Finally, it was badly damaged during the occupation of the Holy Mosque in 1979 . The remains have been deposited and are to be exhibited in the Haram Museum in the future. A small wooden minbar on wheels was then used as a replacement, which, as in pre-Ottoman times, was pushed near the Kaaba for the Chutba. In 2002/2003 King Fahd had a new marble minbar built on wheels with seven steps and a two-winged door. It has been used in the Holy Mosque ever since.

Flooring

As the Meccan historian al-Fākihī (9th century) reports, the floor of the mosque was littered with pebbles for an amount of 400 dinars or less annually until the middle of the 9th century . Taking any of the pebbles from the mosque was not allowed. The Meccan scholar Mujahid ibn Jabr (died 722) is quoted as saying that one should shout when someone violates this commandment. After the Tālibide Ismāʿīl ibn Yūsuf had instigated an uprising in 865, the annual sprinkling of the ground with pebbles ceased. Only when a certain Bishop al-Chādim came to Mecca in 870, this maintenance measure was carried out again. However, the gravel floor was completely washed away in 875 after rains that flooded the mosque. A certain Muhammad al-Lutfī, who had camels in Mecca, then had new gravel brought in from a place called ʿAly and covered the floor of the mosque with it. Al-Fākihī reports that when people settled in the mosque they usually spread felt mats (lubūd) or velvet rugs (ṭanāfis) among themselves.

When Ibn Jubair visited Mecca in the late 12th century, the place where the tawāf was performed was covered with smooth, interlocking stones of various colors (black, brown and white) that looked as beautiful as marble. The rest of the floor of the mosque with the porticoed halls was covered with white sand. In 1426/27 the two Egyptian officials Saʿd ad-Dīn al-Fūwī and Shāhīn al-ʿUthmānī had the entire floor of the Holy Mosque plowed with cattle. The earth was cleared, piled in piles and taken to the lower part of Mecca by workers on donkeys. The floor of the mosque was then re-covered with finely sieved gravel from Dhū Tuwā in the lower part of Mecca and from Wadi at-Tunbudāwī.

In 1594 the matāf, i.e. the place where the tawāf was performed , was paved with real marble. In addition, four walkways were laid that connected the Matāf with the Peace Gate, Safā Gate, ʿUmra Gate and Hazwara Gate. When Johann Ludwig Burckhardt visited Mecca in 1814, the number of these sidewalks had already increased to seven. They were wide enough for four to five people to walk on them, and were about nine inches above the ground. Like the floor in the arcades, they were paved with plaster stones.

On the ground between the sidewalks, which was still covered with pebbles, jugs of Zamzam water lay in long rows during the day. The water that came out of these jugs caused grass to grow in places. The gravel was also often soaked with cleaning water. As the afternoon prayer approached, the Mutauwifs spread kilims and prayer rugs on the gravel for the pilgrims to perch on. However, some people also sat directly on the gravel and spent several hours on it while they waited for the Friday prayer and the chutba . It was not until 1979 that the mosque courtyard was completely paved with stone slabs, so that now its entire area could be used for the tawāf.

Flood prevention devices

A climatic peculiarity of Mecca is that it often comes to heavy rains with floods of great extent. Many of these floods also submerged the Holy Mosque. It was particularly prone to such floods because it is located at a particularly low point in the city, which belongs to a wadi , the so-called Wādī Ibrāhīm. As can be seen from the Chronicle of al-Azraqī , there were already several flash floods (suyūl) triggered by rainfalls in early Islamic times , which submerged the Holy Mosque.

The mosque's susceptibility to flooding increased when, when al-Mahdī expanded the mosque to the south in 780, the original water bed, over which these flash floods ran, was covered and incorporated into the mosque. As al-Azraqī reports, the builders had therefore raised strong objections to the plan to expand the mosque in this direction, but the caliph disregarded these concerns. In order to keep the damage as low as possible, the gates for the expansion of the mosque were laid out in such a way that in the event of flash floods coming from the Wādī Ibrāhīm from the north, the water could flow through the mosque as far as possible without touching the Kaaba: It was supposed to flow in through the Banū-Hāshim gate and drain through the Hizāmīya gate on the opposite side. Later, a canal was built below the Banu Jumah Gate through which the water could drain underground. This underground canal continued to exist after the western outer courtyard was built and was renewed several times, for example at the beginning of the 16th century. The Egyptian official Shāhīn al-ʿUthmānī also had steps built from the outside at the gates of the mosque in 1426/27 to protect the mosque from flooding. The flood protection of the Holy Mosque often did not work, however, because the lower, western part of Mecca was flooded by another torrent during heavy rainfalls, so that the water could not flow away in this direction and was stuck in the mosque. This resulted in severe flooding of the Holy Mosque roughly once every ten years, which required extensive cleaning and repair measures.

Another problem was that during floods, the street south of the mosque, through which the floodwater flowed, was regularly covered with mud, which over time caused a sharp rise in the ground here. Of the 15 steps that you originally had to climb to the mosque, only about three were visible in the 1570s. So it happened that during a heavy rain on 10th Jumādā I 983 (= 17th August 1575) the Holy Mosque was flooded again, even before the Ottoman work on its redesign was completed. The water penetrated into the mosque courtyard and rose so far that it covered the black stone . The water in the mosque yard stood for a day and a half, so that no prayers could be held there during this time. In order to avoid future floods, the Ottoman master builder Ahmad Beg had the floor of the street on the south side of the Holy Mosque, which served as a drainage channel for flood water, lowered at his own expense. In addition, the houses and madrasa schools standing there , which obstructed the drainage of the water, were demolished in order to enlarge this canal . One of the buildings that fell victim to this action was a ribāt belonging to the Bahmani Sultan of Gulbarga . Ahmad Beg also had a wide underground canal called al-ʿInaba built on the north side of the mosque at the Ziyāda gate, where the rainwater from the mountains Quʿaiqiʿān, al-Falaq and al-Qirāra, which drains the water from them when there is a flood Bergen drained underground to the Ibrāhīm Gate, from where it could then flow into the lower part of Mecca. This was to prevent water from entering the mosque from this side during flash floods.

Qutb ad-Dīn an-Nahrawālī, who witnessed these construction works, pointed out in his chronicle the need to inspect the two drainage channels every two or three years and to clean them of accumulated soil in order to prevent future flooding of the Holy Mosque. He also recommended that the Ottoman Sultan stipulate this in a law so that he would not have to reorder it every time. Apparently, his recommendations were not followed, because in the period that followed, the Holy Mosque was repeatedly flooded. One of the worst floods occurred in 1630. During this flood, the Kaaba was badly damaged and some of it collapsed. After a flood in 1681 that flooded the Holy Mosque again, the steps on the outside of the mosque were raised to prevent water from entering the mosque in the future. But this measure did not have much effect either. Other severe flash floods that submerged the Holy Mosque occurred in 1696, 1861, 1909 and 1941.

During the first Saudi expansion of the mosque, a new covered drainage channel was built to ward off floods. It is five meters wide and four to six meters high and directs the water of the flash floods coming from the Wādī Ibrāhīm south of the mosque.

lighting

The Meccan historian al-Azraqī reports that his ancestor ʿUqba ibn al-Azraq was the first to introduce lighting for those who went around the Kaaba at night. He was able to do this because his house was right next to the Kaaba. He put a large lantern on the wall. The caliph Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān (r. 661-680) then regularly allocated lamps and oil to the mosque from the state treasury. When Chālid al-Qasrī took over the governorship of Mecca under ʿAbd al-Malik, he installed a lamp at the Zamzam spring and at the same time forbade the ʿUqbas family to continue lighting their house.

The early Abbasids attached much greater importance to the lighting of the mosque: It was now illuminated at night with a total of 455 hanging lamps. The caliph al-Wāthiq (r. 842–847) had ten long brass pillars built around the Kaaba on which lamps for the people who performed the tawāf were hung. They came from the castle of the Bābak in Armenia, where they had lit the courtyard of his house. After the execution of Bābak in 838 they were sent to Mecca by al-Muʿtasim (r. 833-842). Al-Wāthiq also had eight brass chandeliers hung in the Holy Mosque, two on each side. They were only put into operation in Ramadan and during the pilgrimage season.

Around the middle of the 14th century, 32 new columns were erected around the Matāf, the place where the Tawāf was performed. 18 of them were made of plaster-covered bricks, 14 of finely chiselled stone. Wooden poles were attached to these pillars from which lamps were hung. Overall, however, the illumination of the mosque at this time was considerably more modest than in the early Abbasid period. Taqī ad-Dīn al-Fāsī (died 1429) reports that in his day it was only lit with 93 lamps. Thirty of them hung on the pillars around the Matāf, eleven on the north side of the mosque, eight on the south side and seven on the east and west sides respectively. Five more hung on each of the four maqāme (see below ), four on the maqām Ibrāhīm, three in the Dār-an-Nadwa outer courtyard, one in the outer courtyard on the west side and one from the outside at the Banū-Shaiba gate. In Ramadan and during the pilgrimage season, however, the number of lamps was increased. For example, 30 additional lamps were hung on the pillars of the Matāf. In the last ten nights of Ramadan, the night before the festival, as well as in the new moon nights of the months Rajab and Rabīʿ I , torches were also lit on the four maqāmen.

In the year 932 (= 1525/26 AD) Sultan Suleyman I had the stone columns around the Matāf replaced by a series of thin copper columns. The pillars were now connected to each other by wire to which the lighting was attached. In the Ottoman period, the mosque seems to have been illuminated more strongly again. As the Meccan historian ʿAlī ibn ʿAbd al-Qādir at-Tabarī (died 1660) reports, there were again 450 lamps in the mosque during his time. 224 of them were on the edge of the Matāf, the rest were in the arcades. The 224 lamps of the Matāf were grouped in 32 candlesticks of seven lamps each. Five of the lamps were lit only for ' Isha ' prayer and then extinguished. The other two burned until morning. When the Fajr prayer was called to prayer , the remaining five were lit again. After the prayer of the Hanafi prayer group, all lamps were then extinguished. In addition to the lamps, 24 candles were lit each night, two for each of the four maqāme and the others around the matāf. On the full moon nights around the middle of the month, however, these candles were not used. The daily consumption of the lamps of the Holy Mosque was 32 to 40 ratls of oil. However, this also included various lamps in religiously significant places outside the mosque. The oil for this was brought from Egypt.

The Meccan historian Muhammad as-Sabbāgh (died 1903) reports that in the late 1830s the mother of the Ottoman Sultan Abdülmecid I sent six brass columns to Mecca that were five cubits long and had a palm-shaped top. They were distributed in the Holy Mosque and placed on stone pedestals. Six lamps were attached to each column. These lamp holders, called “trees” (šaǧar) , remained in the mosque until the early 1940s. In addition, all the domes of the roof were fitted with chains that were lowered and from which glass pots with lamps were hung. Abdülmecit also had iron crossbars attached to the front pillars of the arcades, each with five lamps. These burned from the beginning of the month of Ramadan until the 20th Dhū l-Hiddscha . There were a total of 600 lamp pots. There were also 384 lamps in the porticoes, 283 lamps around the matāf and the lamps on the maqāmen, the domes, the gates, the lamp trees and the minarets. In the time of Abdülhamid II (reigned 1876–1909) a total of 1872 lamps were lit in the mosque during the Hajj .

According to Muhammad Tāhir al-Kurdī (died 1980) the lamps used in the Holy Mosque consisted of hemispherical glass vessels with a small base and a wide upper opening without a lid that was easily accessible by hand. A glass was placed in the cavity of each of these vessels, half of which was filled with water and a quarter filled with oil, with the oil floating on top. In the middle of the glass was a fine wick that was lit when night fell. At the edge of the opening of the vessel were three handles with chains attached to hang the lamps.

After the Sherif Husain ibn ʿAlī had made himself independent from the Ottoman Empire in 1916, he replaced the oil lamps in the mosque with kerosene lamps from the Joseph Lucas & Son company . In 1920 he introduced electric lighting in the mosque by illuminating the matāf with 105 light bulbs . They were powered by a generator with an output of 3 kilowatts , which was installed in the Umm-Hānī-Madrasa. In 1921 this generator was replaced by a generator that was twice as powerful and could supply a total of 300 lamps in the mosque with electricity. In 1927 an Indian trader from Rangoon donated a new generator with 30 kilowatts to the mosque, which went into operation that same year. Since its output was insufficient to supply 1000 lamps with electricity as planned, another generator with 13½ HP was purchased in 1930 on the orders of the Saudi King Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud . In 1934, the Indian Zamindar Muhammad Muzammilullah Khan (died 1935) finally donated a new generator to the mosque, which was powered by a 52 hp engine. She was picked up by the Meccan electrical engineer Ismāʿīl Dhabīh in India. He also brought cables, lamps, chandeliers, and spotlights that Muslims from Lucknow , Kanpur, and Karachi had donated to the Holy Mosque. The new plant was put into operation at the end of 1934. The output of the new generator was sufficient to operate 1,300 electric lamps. They had the luminosity of around 35,000 candles and thus illuminated the mosque 20 times more than the oil lamps that had been in use 20 years earlier.

After the Saudi Electricity Company was founded by the Juffali brothers and a general electricity network was set up in Mecca, the al-Haram Mosque was connected to this electricity network on Safar 14, 1373 (= October 23, 1953), thereby creating the possibilities for electrical power Illumination of the building complex was once again enlarged. During the third expansion after 1988, the mosque was fitted with chandeliers, lanterns and fluorescent lamps inside , and particularly powerful spotlights were attached to the edges of the roof to illuminate the inner courtyard and roof surfaces, “which turns night into day”.

Sun protection devices

Since the solar radiation is particularly strong in Mecca, efforts have been made again and again to shield the mosque courtyard with shady elements. For example, as early as the late 7th century, the companions of ʿAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair pitched tents in the mosque courtyard to protect them from the sun . And during the caliphate of Hārūn ar-Rashīd (r. 796–809), sun protection devices for the muezzins were installed at the mosque . So far, they had been sitting in the sun on the roof of the mosque during the Friday service in summer and winter. Hārūn ar-Rashīd's governor ʿAbdallāh had a shade roof (ẓulla) built for them on the roof , from which they could sound the call to prayer while the Imam was on the minbar. The caliph al-Mutawakkil had this shade roof torn down during a renovation of the mosque in 854/55 and rebuilt in a larger form.

The Meccan historian ʿUmar Ibn Fahd (died 1480) reports that in 1406 the Sultan of Cambay in Gujarat sent a number of tents as a gift to the Sherif of Mecca . In an accompanying letter, he said that he had heard that the people in the Holy Mosque on Friday would not find anything that could give them shade while listening to the Chutba . Since a number of scholars would have found it good that people could take this opportunity to protect themselves from the sun, he sent the tents. The Sherif had the tents pitched around the Kaaba for a short time. Then there were complaints because people stumbled over the tent ropes, whereupon they were brought to him. In the early 15th century, some pilgrims put up tents again in the mosque yard to protect themselves from the sun. However, since there were mixed societies of men, women and children in these tents, some of whom were very noisy, the tents were banned.

The setting up of tents in the mosque courtyard was briefly revived at the beginning of the Saudi rule. When the number of pilgrims was particularly high in the Hajj of 1927, which fell in June, and the space in the mosque became narrow, the Saudi king had such tents set up in the mosque courtyard so that the prayers could be protected from the prayers during the midday and afternoon prayers Could find sun. More than 10,000 pilgrims prayed in these tents. In the years that followed, ʿAbd al-Azīz had awnings set up on the four sides of the courtyard during the pilgrimage season to provide shade for the pilgrims from the midday heat. They were removed after the pilgrims left. After the first expansion of the Holy Mosque, these sun protection devices were completely removed.

Buildings adjacent to the mosque

In order to offer accommodation to pilgrims who stayed in Mecca after the end of the pilgrimage to study religious sciences in the Holy Mosque, various Muslim rulers and private individuals had madrasas built on the sides of the mosque from the 13th century . Among the most significant madrasas that were built around the Holy Mosque were three dedicated to the four Sunni disciplines , namely:

- the Ghiyāthīya madrasa in the southwest corner of the mosque. It was founded in 1410 by the Bengali sultan Ghiyāth ad-Dīn Aʿzam Schāh (r. 1390-1410).

- the Madrasat al-Ashraf Qā'itbāy between the mosque and the Masʿā, i.e. the running route between as-Safā and al-Marwa . It was founded in 1480 by the Mamluk sultan al-Malik al-Ashraf Qā'itbāy (r. 1468-1496) and received a sabīl , a minaret, a ribāt and a library .

- the Madāris Sulaimānīya on the north side of the mosque between the northeast corner and the Bāb az-Ziyāda. It was built between 1565 and 1570 by order of the Ottoman sultan Suleyman I (r. 1520–66).

Evliya Çelebi (died 1683) mentions that in his time there were a total of forty madrasas on the four sides of the Holy Mosque. However, these facilities soon lost their function as educational institutions because they were misused as hostels or their foundation assets were misappropriated. Administrators and officials made their own homes in the buildings, renting out the apartments, valued because of their proximity to the mosque, to distinguished pilgrims or wealthy residents of Mecca, so that only the names remained of these institutions. When Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje stayed in Mecca for several months at the end of the 19th century, many Meccans advised him on arrival to rent one of the available madrasas in whole or in part. He sums up the situation of the Meccan madrasas in his time with the words: