Siege of Sarajevo

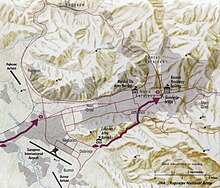

The siege of the city of Sarajevo by the army of the Bosnian Serbs (VRS), units of the remaining Yugoslav federal army and paramilitaries was one of the central events in the Bosnian war . It followed the declaration of independence of the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina with its capital Sarajevo from Yugoslavia .

It began with the capture of the international airport in the suburb of Ilidža by the Yugoslav People's Army on the night of April 4th to 5th, 1992 and ended on February 29th, 1996 with the intervention of western states. At 1,425 days, it was the longest siege in the 20th century . The airlift , which was maintained to supply hundreds of thousands of trapped people, lasted longer than the Berlin airlift .

It is estimated that around 11,000 people (including 1,600 children) were killed and 56,000 injured, some seriously, during the siege.

course

Start of conflict

On the Serbian side, March 1, 1992 is often cited as the beginning of the fighting in Sarajevo. On that day, the Bosnian soldier Ramiz Delalić shot a wedding party in the historic Baščaršija district , killed the 55-year-old Serb Nikola Gardović and injured a priest. Delalić was not arrested after the fact, but was later given the command of the 9th Brigade of the Bosnian Army. He was only charged with murder in 2004, but no verdict was reached because Delalić was murdered by unknown perpetrators in front of his home on June 27, 2007.

From a Bosnian perspective, it is officially April 5, 1992, when snipers from the Kovačići district shot at a crowd of demonstrators on the Vrbanja Bridge , killing the 25-year-old Bosnian Muslim medical student Suada Dilberović and the 34-year-old Croatian Olga Sučić . The bridge on which both were killed now bears their names. The two women were out with other demonstrators for a peace demonstration on the forecourt of Parliament. Another demonstrator died on the bridge and four were injured. Shortly thereafter (2 p.m.) snipers from the Vraca district above opened fire on the bridge to the west (today Hamdije Čemerlića Bridge), injuring a civilian so seriously that he later died in hospital. The demonstrators were not deterred by this, penetrated the parliament building and declared it an "open people's parliament". In the course of the afternoon, more and more residents flocked to the peace demonstration and kept parliament occupied during the night, which is why Radovan Karadžić ordered some parts of the city to be closed on April 6th. When Karadžić received information that the assembled crowd was considering a peace march into the Serbian-dominated district of Vraca, he threatened to continue using firearms if he entered "Serbian territory". Although the march to Vraca did not take place, around 2 p.m. snipers from the Hotel Holiday Inn across from Parliament opened fire on the peace demonstration and injured seven people. The Holiday Inn was the headquarters of Karadžić's Serbian Democratic Party at the time . When the Bosnian police began to arrest several armed Serbs found at the hotel, Serb paramilitaries stormed the city's police academy, took several hostages and forced the alleged perpetrators to be released.

By the beginning of April 1992, units of the Yugoslav Federal Army had gathered hundreds of artillery pieces, tanks and mortars on the ridges around the city. In April 1992 the Bosnian government requested the withdrawal of these troops. The Milošević government promised the withdrawal of the non-Bosnian-Herzegovinian fighters, a rather insignificant number. The Bosnian-Serb units of the Yugoslav Federal Army were added to the army of the Republika Srpska , which proclaimed its independence from Bosnia and Herzegovina only a few days after Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence. The Croatian President Franjo Tuđman , however, continue to let Croatian Defense Forces ( Croatian vijeće obrane ) on the part of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Croats station.

The 4th Corps of the Federal Army, which had concentrated in the surrounding hills of the city, became the Sarajevo-Romanija Corps of the Army of the Republika Srpska . The Sarajevo-Romanija Corps took over all heavy weapons of the 4th Corps and was brought back to normal strength through the integration of paramilitaries from Serbian-controlled areas. In addition, troops of the federal army took over the international airport on the night of April 4 to 5, 1992 and handed it over to the Serbian troops. Thus Sarajevo was surrounded by Serbian troops.

Blockade and siege of the city

On May 2, 1992, the Bosnian-Serb forces officially blocked the government-controlled part of Sarajevo. The main arterial roads to the city center were closed and the city was no longer supplied. The water and electricity supplies were cut. In terms of armament and numbers, the Serbian fighters around the part of Sarajevo controlled by the government troops were far superior to the defenders. Nevertheless, the goal of conquering the city was not achieved.

The second half of 1992 and the first half of 1993 were the climax of the siege of Sarajevo. Violent military conflicts took place. Meanwhile, some Serbian residents of the city had begun openly supporting the besiegers. The city's most important defenses and weapons depots were in Serb hands. A number of districts with a high Serbian population, such as Novo Sarajevo, were captured by Serbian associations.

At that time, many civil buildings were attacked. According to reports, 35,000 buildings across Sarajevo had been destroyed in September 1993 and nearly all the rest were more or less damaged, including hospitals, media and news centers, industrial plants, government buildings, barracks and United Nations bases . Among the more important of these buildings was the presidential residence of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the national library with thousands of irreplaceable works, which burned down on August 25, 1992 after targeted fire.

The shelling of the city cost many lives. Dozens were killed and hundreds injured in individual bombardments. The besiegers complained to the UN authorities that they had been shot at from the city and that for this reason they had returned fire.

The 800 meter long Sarajevo tunnel was completed in mid-1993. He made it possible for people (e.g. injured) to leave the trapped city, as well as to provide food, medicine and weapons.

Capture of the president and attack on withdrawing JNA troops

The Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović was on his way back from peace talks with the European Community in Lisbon on May 2, 1992 , when he and his daughter and his bodyguard were captured by Bosnian Serb troops at Sarajevo Airport and taken to the barracks of the Federal Army Serbian occupied Lukavica was spent. The order for this had been given by the commander of the Federal Army in Bosnia, General Milutin Kukanjac , who at that time was with about 270 men in the headquarters of the Federal Army in the city center and was besieged by Bosnian government troops .

In a televised telephone conversation between General Kukanjac, President Izetbegović and Bosnian Vice-President Ejup Ganić , General Kukanjac called for himself and his men to withdraw freely from Sarajevo under UN protection. Until then, the president was being held for his own safety . Izetbegović entrusted Ganić with government affairs until further notice and gave his consent for the general to leave. The withdrawal of his men was to be renegotiated at a later date. Ganić was furious about the president's arrest and called for his immediate release.

With the help of the UN, an agreement was reached the next morning; President Izetbegović was to be brought in a UN convoy from the barracks in Lukavica through the Serbian-controlled area and past the Bosniak troops to the grounds of the army headquarters in the city center, where General Kukanjac was to board. The President and the General were then to be brought to the front line at the Bosnian Presidium and received there by their own troops.

But after the UN convoy arrived at the army headquarters, Kukanjac suddenly asked for all soldiers from the headquarters to be withdrawn and for their equipment, weapons and files to be taken with them. However, UN Commander Lewis MacKenzie was only prepared for the safe transport of individual people, which is why renegotiations were carried out on site. Finally it was agreed that the soldiers of the Federal Army should follow the armored UN vehicles in their vehicles. Izetbegović and the commander of the Bosniak armed forces, Sefer Halilović , promised their protection.

But shortly after departure, the convoy was completely surrounded by Bosniak troops and brought to a standstill. The combat troops ( 1st Corps ) under Jovan Divjak allegedly did not yet know about the renegotiations due to communication problems and refused to allow those people to withdraw who had ordered and directed the attack on Sarajevo the day before. The Bosnian Serb soldiers in their vehicles were forced to surrender their weapons and equipment, and there were occasional assaults and murders. The Bosniak commanders on the spot had difficulty stopping their men’s attacks. In front of the camera, Commander Divjak tried for about half an hour by radio and loudspeaker to stop the attacks by the Bosniak troops and to set the convoy back in motion, which he finally succeeded in doing. The President and General were then brought to safety and received by their troops.

Snipers

In the besieged city acted snipers . They positioned themselves mainly in the tall buildings on the wide main road Zmaja od Bosne and shot at random vehicles and people. This street was therefore often called "Sniper Alley" (Bosnian: Snajperska aleja ). Mountains near the city were also used as sniper sites. Signs reading Pazi - Snajper! ( Caution - sniper! ) Were common. Objects (for example, containers or wooden walls) were placed on some stretches of the road, and they could be used as a privacy screen.

According to data collected by the ICTY , the snipers killed 253 civilians and 406 soldiers between September 10, 1992 and August 10, 1994 alone. Over 60 children were among those killed. During the same period, 1,296 civilians and 1,815 soldiers were injured by sniper gunfire. The victims included not only local men, women and children, but also journalists, members of aid and rescue organizations and UN soldiers . In particular, the area around the Hotel Holiday-Inn , which was considered a shelter for numerous war reporters and journalists, received the reputation of a "death zone". Between Bosnian (e.g. Dobrinja) and Serbian (e.g. Grbavica) parts of the city there were duels by snipers, and in isolated cases targets were shot at from both sides. The recovery of the wounded and dead often took hours, in some cases even days, as the rescue teams arriving also came under fire.

The two commanders of the Bosnian Serbs ( Stanislav Galić and Dragomir Milošević ) were massively accused of planning and ordering the use of regular army snipers against civilians. They claimed, however, that the Bosnians would fire shots at compatriots themselves in order to induce the UN to intervene against the Serbs. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia acknowledged that Bosnian soldiers may on occasion have tried to gain international sympathy by ambushing compatriots themselves, blaming the Serbian attackers. However, most of the attacks have been shown to have been carried out from Serb-held positions.

Grenade fire

During the siege, an average of 329 shells hit Sarajevo every day . The peak of 3,777 shell impacts was recorded on July 22, 1993. The bombardment caused immense damage, especially to civil and cultural property and values. Armed forces of the Bosnian Serbs and the Bosnian Army bombed civil targets of the other ethnic group in Sarajevo, including hospitals, markets, mosques and churches.

On May 27, 1992 a mortar shell hit the market in Vase Miskina Street . 22 people were killed and around 60 others were seriously injured. The attack came to be known as the "Breadline Massacre" because it only affected civilians waiting for bread to be distributed.

On June 1, 1993, two 82 mm mortar shells struck a group of football fans watching a game in the Dobrinja district, killing 15 spectators and injuring another 100. On July 12, another 82 mm mortar shell struck Dobrinja district and killed twelve people waiting for water to be distributed. 15 other people were injured.

The most lossy shell impact occurred on February 5, 1994, when a 120 mm mortar shell struck the crowded Markale market square, killing 68 people and injuring 144. On August 28, 1995, five more mortar shells struck, among other things, the street leading past the market, killing 37 people, and injuring 90 others ( Markale massacre ).

Falconara – Sarajevo airlift

An international airlift began on July 3, 1992, to supply hundreds of thousands of trapped people. The UNPROFOR had previously taken control of the airport on June 29 1992nd The Falconara – Sarajevo airlift from Ancona Airport in Italy lasted until January 9, 1996. From April 8 to September 15, 1995, the flights were suspended for safety reasons. From July 1992 to January 3, 1995, German, French, British, American and Canadian transport planes carried 11,312 flights to Sarajevo with almost 126,000 tons of food and 14,000 tons of medical supplies. They also transported blankets, tents, sheeting (to replace the window panes that had been destroyed everywhere), gas and water pipes.

On September 3, 1992, an Italian Aeritalia G.222 was shot down over Jasenik, around 20 miles west of Sarajevo, killing the four crew members. The machine was approaching the city and was probably hit by an anti-aircraft missile. At the time of the shooting down, fighting was raging between Croatian and Serbian troops in the area. Italy then stopped further aid flights to Sarajevo.

The German Bundeswehr also used C-160 Transall transport machines , which flew 1,412 missions to transport around 10,800 tons of relief supplies and to move 3,875 people. On February 6, 1993, a Transall of Lufttransportgeschwader 62 was shot at on approach for landing and a crew member was seriously wounded. During the relief flights, the landing maneuver, later known as the Sarajevolandung , was also carried out by the Transall aircraft: the Transall flew very steeply to Sarajevo airport from an altitude of 6,000 meters. Only shortly before the ground did the pilot intercept the machine and touch down on the runway. This had the advantage of being out of the range of handguns for as long as possible.

On January 4, 1996, a Transall of the German Air Force flew the last aid flight.

Intervention by NATO

On May 6, 1993, the United Nations Security Council decided to declare the cities of Bihać , Goražde , Sarajevo, Tuzla and Žepa besieged by Bosnian-Serb troops as UN protection zones . All warring parties were asked to end the armed attacks and hostile acts in these areas and to regard the protected areas as safe areas. The United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), resolved in February 1992, was deployed to secure the protection zones , made up for the most part of French and British as well as smaller contingents from around 20 other countries.

During the siege, UNPROFOR's tasks included maintaining the airlift over the airport and supplying the population with relief supplies, as well as taking other measures to protect the civilian population in the city. Armored vehicles helped pedestrians pass dangerous sniper lanes. In addition, barricades were erected to protect against snipers by driving trams into position or bringing containers, board walls, trucks or destroyed vehicles into position. UN vehicles were one of the few modes of transportation in the city. Electric lines were also repaired and rubbish was removed.

From June 1993 onwards, UNPROFOR had two options on the basis of Security Council Resolution 836 to react to attacks and threats with NATO air strikes. The first was close air support . This could be requested if a UN target should be exposed to a direct attack. It had to be verifiable which gun had fired. In general, an unequivocally identified “ attack of smoking guns ” was required . The close air support soon proved to be almost useless as the chain of command was far too long and the besiegers developed tactical defensive measures. A request from six leading people in three countries had to be approved before a Forward Air Controller (FAC) was allowed to mark the identified target with a laser. The average time between requests for help and approval of the attack was about twelve hours. The Serbs thus had more than enough time to regroup their forces after an attack and move the tank or gun that had fired out of sight of NATO.

The second variant was the air raid . In contrast to close air support, air strikes were not limited to a specific target, but enabled attacks on the entirety of a military machine. These included, for example Military vehicles and troops as well as barracks, bridges, supply routes, ammunition and fuel stores. However, these air strikes were intended only as a deterrent and a last resort so as not to escalate the conflict. Above all, acts of revenge against the numerically and technically inferior UN soldiers were expected. This reluctance, however, strengthened the besiegers in their offensive approach.

In August 1992, the Serbian troops were on the verge of taking the Igman mountain south of Sarajevo , over which the only road to the capital still controlled by Bosniak troops ran. Only when the USA threatened air strikes did the Serbian troops withdraw again. As the city's only lifeline at times, the road over the mountain, monitored by UN troops, remained a thorn in the side of the Serbs.

On February 5, 1994, the infamous Markale massacre occurred in Sarajevo city center . A mortar shell had detonated near the Markale market hall, killing 68 people and injuring 144 others. As a result of this massacre, for which Serbs and Bosniaks accused each other, an ultimatum from the UN Security Council followed four days later to withdraw all heavy weapons within ten days from a radius of 20 km from Sarajevo's city center or to place them under UN supervision, which was initially respected by the Serbs.

On August 5, 1994, despite the threat of NATO air strikes, Serbian troops stole heavy weapons from a UN depot in Ilidža within the exclusion zone. This was followed by the first NATO air strike in the Sarajevo area; two US warplanes destroyed a Serbian tank destroyer, whereupon the weapons were returned. On September 22, 1994, however, the Serbs once again disregarded the exclusion zone, stole tanks from UN depots and shot at NATO troops. After the threat of air strikes, the Serbs withdrew again. There continued to be isolated intrusions by Serbian tanks, artillery pieces and mortars, which opened fire on targets in the city and then withdrew from the prohibited zone. These attacks had almost no consequences for the Serbs.

On May 7, 1995, the Butmir exit of the Sarajevo tunnel was shot at from the prohibition zone , killing ten civilians. Thereupon the Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović sent a protest note to the UN Secretary General , recalling the existing resolutions as well as the numerous attacks by the Serbs from within the prohibited zone, which went unpunished, and called the UN's failure to intervene a shame. The next day, General Rupert Smith demanded, in retaliation for the previous day's attack, air strikes on a heavy mortar, multiple rocket launcher and a Serb command bunker, but received no clearance. On May 22, 1995, Serbian troops again transport heavy weapons from a UN weapons depot. On May 25, after the Serbs ignored an ultimatum to return heavy weapons, Smith ordered an air strike on two Serb ammunition dumps near Pale that same day. The Serbian answer was harder than expected; UN soldiers have been taken hostage by Serbs and barrages have started on UN protection zones across the country. In a single shell hit in Tuzla alone , 71 civilians were killed and 173 were injured. 53 of those killed were younger than 25 years. After the shelling of Tuzla, NATO launched another air raid on ammunition stores, air defense positions and communications facilities near Pale. The Serbs then took 370 UN soldiers hostage and chained them to strategically important positions in order to prevent further air strikes. If air strikes continued, there was an open threat of murder of UN troops.

The first state to take more decisive action against the Bosnian Serbs was France, which feared for its reputation after the capture of French UN soldiers. Another slap in the face was on May 25, 1995, when Serbian troops captured the UN post at the strategically important Vrbanja Bridge in the city center without a fight and captured twelve French UN soldiers. The Serbs had previously captured French uniforms and vehicles to deceive the French. On the same day, the French counterattacked across the bridge and retook the post after a long skirmish, killing four Serbian soldiers and capturing four more. The French had two killed and 17 wounded. On August 24, 1995, a Serbian barrage hit the city in which 49 civilians were killed or injured and six UN soldiers were seriously wounded. As a result, French UN troops fired for the first time with heavy artillery at the Serbian firing position determined by radar.

On August 28, 1995, Serbian troops fired five mortar shells from the protection zone on Markale market, killing 37 civilians and injuring 90. Now, NATO decided to take more forceful action against the Serbs and two days later launched Operation Deliberate Force , during which numerous Serbian targets were bombed in the hills and mountains around Sarajevo. On August 30, the Serbs succeeded in shooting down a French Mirage 2000 fighter plane , the pilots of which both got out with the ejector seat and were captured by the Serbs. The French then bombed Pale. By September 21, 1995, Serbian command structures, ammunition depots, barracks, strategically important bridges and air defense positions were eliminated.

Electricity and water supplies could be restored in the Bosniak part of the city. In October 1995 a ceasefire was first agreed and the Dayton Treaty was later signed.

Even if this was followed by a period of stability and normalcy, the Bosnian-Herzegovinian government only officially declared the end of the siege of Sarajevo on February 29, 1996.

literature

- Historijski muzej Bosne i Hercegovine , (City) Sarajevo (Ed.): Opkoljeno Sarajevo . Sarajevo 2003. (Booklet to the permanent exhibition, Bosnian / English).

See also

- Roses from Sarajevo

- Vedran Smajlović (also known as the cellist of Sarajevo )

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Final report of the United Nations ( Memento of the original from March 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved March 15, 2011

- ↑ http://www.krone.at/Welt/Ausloeser_des_Bosnien-Krieges_getoetet-Unterwelt-Boss-Story-72298 "Trigger" of the Bosnian War killed.

- ↑ How the Civil War Started in Bosnia. srebrenica-project.com, January 7, 2009

- ^ Holm Sundhaussen: Sarajevo. The story of a city. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2014, p. 324 f .

- ^ Gustav Chalupa: War and media in the Balkans. P. 150

- ^ Holm Sundhaussen: Sarajevo. The story of a city. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2014, p. 317 .

- ^ Robert J. Donia Sarajevo: A Biography. P. 297

- ↑ http://www.sarajevo-airport.ba/tekst.php?lang=eng&id=6&kat=2 Short historical overwiev.

- ↑ Radha Kumar: Divide and Fall - Bosnia in the annals of partition. P. 54

- ^ Jeanne M. Haskin: Bosnia and beyond. P. 65

- ↑ http://www.slobodan-milosevic.org/documents/P3731.pdf Population Losses in the Siege of Sarajevo.

- ↑ http://www.cpj.org/killed/europe/bosnia/ 19 Journalists Killed in Bosnia since 1992.

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/serb-snipers-attack-sarajevo-civilians-1441973.html Serb snipers attack Sarajevo civilians.

- ↑ Emma Daly: Sniper takes aim at Sarajevo and claims first victim of truce. The Independent, February 17, 1994

- ^ Muslims not welcome, not matter where they come from. www.sense-agency.com

- ^ Kurt Schork's signature dispatch from siege of Sarajevo. http://www.ksmemorial.com

- ↑ 20 years imprisonment for Serb general. Wirtschaftswoche, December 5, 2003

- ↑ 20 years imprisonment for the commander of the snipers in Sarajevo. Die Welt, December 6, 2003

- ↑ http://www.literaturkritik.de/public/rezension.php?rez_id=12819 Art as a unifying force against horror.

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/world/1993/jun/02/warcrimes.fromthearchive Blood and tears end a soccer game which no one could win.

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/serbs-kill-12-waiting-in-queue-for-water-1484593.html Serbs kill 12 waiting in queue for water .

- ↑ http://www.scribd.com/doc/38928955/General-Michael-Rose-Serbs-Responsible-for-Markale-Market-Shelling Serbs Responsible for Markale Market Shelling.

- ↑ PA_FOC: UN AIRBRIDGE: Lifeline for Sarajevo. In: Focus Online . January 9, 1995, accessed October 14, 2018 .

- ↑ Chuck Sudetic: UN Relief Plane Reported Downed on Bosnia Mission. New York Times, September 4, 1992