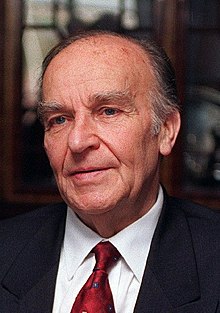

Alija Izetbegović

Alija Izetbegović [ izɛtˈbɛ̌ːgɔvitɕ ] (born August 8, 1925 in Bosanski Šamac , Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes ; † October 19, 2003 in Sarajevo , Bosnia and Herzegovina ) was a Bosnian politician , Islamic activist, founder and party leader of the Democratic Party Aktion (1990–2001), first President of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1990–1995) and leading member of the collective state presidency (1996–2000).

In 1992 he declared his country's independence from Yugoslavia as a result of an internationally monitored referendum .

In 1993 he received the King Faisal Prize for services to Islam.

Life

Alija Izetbegović was born as the son of an accountant in the northern Bosnian town of Bosanski Šamac in a respected but impoverished family of originally noble origins. When Izetbegović was two years old, his father, who had fought in the First World War in the Austro-Hungarian army on the Italian front and returned seriously injured, had to declare bankruptcy, and the family moved to Sarajevo. Alija Izetbegović grew up there in a secular atmosphere and attended a German school. During World War II , at the age of fifteen, he joined the group of Young Muslims ( Mladi Muslimani ), a politico-religious group based on the Muslim Brotherhood movement of Egypt that was divided over the course of the war over whether it was the SS-Handschar or the royalist Chetniks should support. At that time, Izetbegović sided with the SS Handschar and was captured by the Chetniks in the summer of 1944, but released by their commander Dragutin Keserović .

After the end of the war, Izetbegović began studying law at the University of Sarajevo . Under the communist government formed by Tito in Yugoslavia in 1946, he was sentenced to three years in prison by a military court for his war activities. The Croatian-British historian Marko Attila Hoare, however, takes the view that the real reason for his condemnation was his opposition to the new communist government.

Izetbegović completed his law studies in Sarajevo in a record time of only two years. He married his childhood sweetheart Halida Repovac and remained politically active. In 1956 his son Bakir was born. In addition, Izetbegović had two daughters. After graduating, he worked for a construction company in Montenegro for seven years and also wrote political and religious works.

Political career

In 1970, Izetbegović published the Islamic Declaration Manifesto , which rejected the "modernists" in the Islamic world as clearly as they did the "western civilization". The main demand of the declaration was the “Islamization of the secularized Muslims” on the model of Pakistan . The author speaks out clearly and unequivocally for the incompatibility of Islam with any other religious and social order, while at the same time turning away from the principle of the separation between state and religion :

“ The first and foremost [knowledge] is certainly that of the incompatibility of Islam with non-Islamic systems. There is no peace or coexistence between the "Islamic faith" and non-Islamic societies and political institutions. (…) Islam clearly excludes the right and the possibility of activities of a foreign ideology in its own field. Therefore any secular principles are out of the question, so the state should be an expression of religion and it should support its moral concepts. "

The declaration also called for a pan-Islamic state in which Muslims should merge into a community in which Islam would be the ideology and pan-Islamism would be the policy. It also says: “Our goal: the Islamization of Muslims. Our motto: Believe and Fight. ”In 1980, his book Islam between East and West was published , in which he tried to define the place Islam occupies among other great ideas. Because of his writing Islamic Declaration , which was banned in Yugoslavia and therefore circulated illegally, he was sentenced in 1983 to 14 years in prison. The Yugoslav government accused him of conspiratorial plans to establish an Islamic state. However, he was released from political detention in 1988 to calm the tense situation in Kosovo at the time .

In 1990 Izetbegović, u. a. together with the previously loyal businessman Fikret Abdić , who later became his rival, the Party of Democratic Action (SDA) . The SDA did not have a national name in its name, but emerged as the winner of the elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina on November 16 as a representative of the Muslim ethnic group - like the nationally oriented parties of the Croatian population ( HDZ ) and the Serbs ( SDS ). Although Abdić got the most votes in the presidential elections taking place at the same time, Izetbegović took over this office after internal discussions. In a coalition of the three leading national parties aimed at achieving a balance between the ethnic groups, Izetbegović became President of Bosnia-Herzegovina; next to him, the SDS of Radovan Karadžić provided the President of Parliament and the HDZ BiH, which is aligned with the HDZ of the Croatian President Franjo Tuđman , provided the Prime Minister.

Bosnian War

After the Slovenian War and the beginning of the Croatian War, the European Union recognized Slovenia and Croatia on January 15, 1992 as sovereign states and also promised Bosnia-Herzegovina recognition on the condition that the population would vote for independence in a fair referendum . During this phase, Izetbegović signed an agreement on February 23, 1992 to form a confederation with the Bosnian Serbs and Croats .

After representatives of the Bosnian nationalist parties HDZ and SDS met on February 26, 1992 to negotiate the division of the territory, he revised this position. On February 29, he had the referendum proposed by the EU held. The ethnic groups of Croats and Bosniaks voted with over 90% in favor, the Serbs boycotted the vote. The EU recognized the independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina on April 6th.

During the war in Bosnia that broke out and cost more than 100,000 lives by 1995 and led to the displacement of around two million people, Izetbegović lived under precarious circumstances in besieged Sarajevo . He showed himself unwilling to allow the sovereignty of Bosnia or the ethnic division of the country according to the plans of the Serbian and Croatian nationalists, especially since his side - also through massive international support - was growing in strength. After initially half-hearted promises and aid measures by the UN and the international community, the USA under Bill Clinton and the international community increased their military pressure on Milošević and Karadžić after the Srebrenica massacre in July 1995, and also put Izetbegović under political pressure. The Dayton Agreement was negotiated over weeks on a military base in Dayton , in which US negotiator Holbrooke Izetbegović urged him to give way to the interests of the Serbian and Croatian presidents. In the end, the Bosnian leadership was ready to sign the peace treaty in Paris together with the Croatian President Tuđman and the Serbian President Milošević.

post war period

Alija Izetbegović was confirmed in the first post-war elections on September 18, 1996 and, as President of Bosnia, represented his party SDA in the collective state presidency of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which he perceived together with the national representatives Krešimir Zubak HDZ and Momčilo Krajišnik SDS until 2000 withdrew for health reasons. Izetbegović became honorary chairman of his party SDA and remained so until his death.

On September 10, 2003, the 78-year-old Izetbegović suffered a fainting attack after falling in his house and suffered four broken ribs and internal bleeding. His health deteriorated on October 16, 2003 and he had to be transferred to a hospital intensive care unit. The incumbent Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan traveled to Sarajevo to speak with him again. On that day, Izetbegović called for reconciliation in a telephone interview with the private TV broadcaster Hayat in Sarajevo and warned that the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina would only survive if the hatred between the peoples was overcome. At the same time, Izetbegović urged the unity of the state of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks should remain true to their ethnic identity, but “they should all be Bosnians”. About 100,000 people attended Izetbegović's funeral on October 22nd.

The international “High Representative” appointed by the UN after the Dayton Agreement, the former chairman of the British Liberals, Paddy Ashdown , praised Izetbegović's political work with reference to his nickname Dedo (grandfather), whom Izetbegović had among his supporters: “He was in the truest sense the father of his people; without him Bosnia-Herzegovina would probably not exist ”. At the same time, Ashdown called on the Bosnians to continue working on the future of their country as a legacy of Izetbegović.

criticism

Esad Bajtal accused Alija Izetbegović of taking no action against crimes committed by mujahideen units .

"Izetbegović and Rasim Delić , who were in command of these troops, must be accused of having done nothing against the mujahideen and their crimes," said the social scientist, who worked as a journalist in the Breza front town during the war and for a long time later Years of the socially critical writers group 99 chaired. “Now we Bosniaks have to answer for these people.” Sefer Halilović , the first commander of the ARBiH , confirms this criticism. He had been removed from his post because Izetbegović had pursued the Islamization of the Bosnian Defense Forces. The mujahideen and the elite unit "Black Swans" were then also under its direct command.

literature

- Marie-Janine Calic : War and Peace in Bosnia-Hercegovina. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-518-11943-5 .

- Marie-Janine Calic: History of Yugoslavia in the 20th Century. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60646-5 .

- Misha Glenny: The Fall of Yugoslavia. Penguin Group, London 1996, ISBN 0-14-026101-X .

- Hannes Hofbauer : Balkan War. Ten years of destruction of Yugoslavia. Promedia Verlag, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-85371-179-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ J. Millard Burr, Rachel Ehrenfeld: The Muslim Brotherhood: Breaking Rice Bowls , July 22, 2014.

- ^ A Biographical Encyclopedia of Contemporary Genocide. Paul R. Bartrop , p. 140.

- ↑ a b David Binder: Alija Izetbegovic, Muslim Who Led Bosnia, Dies at 78. In: nytimes.com. October 24, 2010, accessed March 13, 2017 .

- ^ Marko Attila Hoare: Bosnian Muslims in the Second World War: A History . Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-932785-0 , pp. 12 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Marie-Janine Calic: War and Peace in Bosnia-Hercegovina. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996, p. 77.

- ^ Translation from the English copy, p. 30; Source see links. Wording in the Bosnian original: “Prvi i najvažniji takav zaljučak svakako je zaključak o nespojivosti islama i neislamskih sistema. Nema mira ni koegzistencije između "islamske vjere" i neislamskih dru štvenih i političkih institucija. … Polažući pravo da sam uređuje svoj svijet, islam jasno isključuje pravo i mogućnost djelovanja bilo koje strane ideologije na svom području. Nema, dakle, laičkog principa, a država treba da bude izraz i da podržava moralne koncepte religije. "Source: " Islamic Declaration " , scribd.com, p. 25.

- ^ Marie-Janine Calic: History of Yugoslavia in the 20th century. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2010, p. 245.

- ^ Marie-Janine Calic: History of Yugoslavia in the 20th century. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2010, p. 325.

- ↑ Bosnian war crimes probe mars Izetbegovic's funeral ceremony. (No longer available online.) In: Ekathimerini English Edition. October 23, 2003, formerly in the original ; accessed on November 16, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Erich Rathfelder: Intersection Sarajevo. Bosnia and Herzegovina ten years after Dayton: Muslims, Orthodox, Catholics and Jews are building a common state . Verlag Hans Schiler, 2006, ISBN 978-3-89930-108-3 , pp. 117 ( preview in Google Book search).

Web links

- Literature by and about Alija Izetbegović in the catalog of the German National Library

- English translation of the Islamic Declaration (PDF file; 3.12 MB)

- Islamic Declaration in the "Open Library" (including Library of Congress number BP163.I9413 1990b)

- Islamic declaration in the original Serbian language

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Izetbegović, Alija |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Bosnian politician and Islamic activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 8, 1925 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bosanski Šamac |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 19, 2003 |

| Place of death | Sarajevo |