Partitions of Poland

With partitions of Poland , the divisions of the double state are primarily Poland-Lithuania designated end of the 18th century. In the years 1772 , 1793 and 1795 , the neighboring powers of Russia , Prussia and Austria gradually divided the Union state among themselves, so that no sovereign Polish state existed on the map of Europe from 1796 to the end of the First World War in 1918 for over 120 years .

After the victory over Prussia in the Peace of Tilsit in 1807, Napoleon I created the Duchy of Warsaw as a French satellite state from the Prussian partition areas of the second and third division . In the Treaty of Schönbrunn he expanded in 1809 by the Duchy of western Galicia , the Austrian division area of 1795. After the defeat of Napoleon in the Napoleonic wars , the reduced 1815 Congress of Vienna it to Poznan and Krakow . The constitutional " Kingdom of Poland " emerged from the duchy, ruled in personal union by the autocratic Emperor of Russia as the "King of Poland".

Based on the three partitions of Poland, the term Fourth Partition of Poland exists , which was later used for various circumcisions of the Polish state territory .

overview

After the aristocratic republic of Poland-Lithuania was severely weakened in the second half of the 18th century by numerous previous wars and internal conflicts (e.g. by the confederations ), the country came under Russian supremacy from 1768 onwards . Tsarina Catherine II called for the legal and political equality of the so-called dissidents , as the numerous Orthodox East Slavic population of Poland-Lithuania was called at the time, but also Protestants . However, this provoked the resistance of the Catholic nobility (see Confederation of Bar 1768–1772).

The Kingdom of Prussia took advantage of this troubled situation and negotiated a strategy for Poland with Russia. Finally, King Frederick II and Tsarina Katharina II succeeded by purely diplomatic means in having large areas of Poland annexed by Austria, Russia and Prussia. Prussia's long pursued goal of creating a land bridge to East Prussia was achieved in this way in 1772.

The state that remained after this first division implemented various internal reforms , including the abolition of the principle of unanimity in the Reichstag ( liberum veto ), whereby Poland wanted to regain its ability to act. The reforms finally resulted in the adoption of a liberal constitution on May 3, 1791 . Such zeal for reform, shaped by the ideas of the French Revolution , contradicted the interests of the absolutist neighboring powers and parts of the conservative Polish aristocracy (see Confederation of Targowica 1792) and in 1793 encouraged a further division, in which Prussia and the Russian Empire participated .

The renewed division met with fierce resistance, so that the representatives of the small nobility with parts of the bourgeoisie and peasant class joined a popular uprising around Tadeusz Kościuszko . After the Kościuszko uprising had been suppressed by the partitioning powers, Prussia and Russia decided in 1795 - again with Austrian participation - to completely divide the Polish-Lithuanian aristocratic republic.

Poland's weakening since the 17th century

As early as the first half of the 17th century , Poland-Lithuania entered a long phase of mostly involuntary armed conflict with its neighbors. In particular, the recurring clashes with the Ottoman Empire (see Ottoman-Polish Wars ), Sweden (see Swedish-Polish Wars ) and Russia (see Russian-Polish Wars ) put a strain on the stability of the Union state.

Second Northern War

Armed conflicts, which shook the union state badly, began in 1648 with the large-scale Chmielnicki uprising of the Ukrainian Cossacks , who rebelled against Polish rule in western Russia . In the Treaty of Perejaslav , the Cossacks placed themselves under the protection of Tsarist Russia , which triggered the Russo-Polish War 1654–1667 . The victories and the advance of the Russians and the Ukrainian Cossacks under Chmielnicki also caused Sweden's invasion of Poland from 1655 (see Second Northern War ), which in Polish historiography became known as the "Bloody" or "Swedish Flood" . At times the Swedes advanced as far as Warsaw and Cracow . Towards the end of the 1650s, when other powers entered the war, Sweden was weakened and put on the defensive to such an extent that Poland was able to negotiate the status quo ante in the Peace of Oliva in 1660 . The clashes with Russia continued, however, and finally resulted in an armistice agreement in 1667, which was unfavorable for Poland , through which the Rzeczpospolita lost large parts of its national territory ( Smolensk , left bank Ukraine with Kiev ) and millions of inhabitants to Russian tsarism.

Poland was not only weakened territorially. In terms of foreign policy, the Union state became increasingly incapable of acting and economically the consequences of the war meant a catastrophe: Half of the population died in the turmoil of the wars or were expelled, 30 percent of the villages and cities were destroyed. The decline in agricultural products was dramatic, with grain production alone only reaching 40 percent of the pre-war level. By the beginning of the 18th century, Poland fell behind in social and economic development, which it was unable to make up for into the following century.

Great Northern War

Nevertheless, the new century began with another devastating war, the Third or Great Northern War 1700–1721 , which is now often seen as the starting point in the history of the partitions of Poland. The renewed clashes for supremacy in the Baltic Sea region lasted for over 20 years . Most of the neighbors formed the “Nordic League” in the Preobrazhenskoe Treaty and ultimately defeated Sweden. The Peace of Nystad in 1721 sealed the end of Sweden as a major regional power .

The role of Poland-Lithuania in this conflict revealed all too clearly the weakness of the republic. Even before the war began, the aristocratic republic was no longer an equal player among the Baltic Sea powers. Rather, Poland-Lithuania fell more and more under the hegemony of Russia. Nevertheless, the new King of Poland and Elector of Saxony , August II , strove to profit from the disputes over the “ Dominium maris baltici ” and to strengthen his position like that of the House of Wettin . The background to these efforts was probably in particular the intention to set a dynastic symbol in order to force the conversion of the Saxon-Polish personal union into a real union and hereditary monarchy (Poland-Lithuania had been an elective monarchy since its foundation in 1569 ).

After Russia had defeated the Swedish troops at Poltava in 1709, the "Nordic League" was finally under the leadership of the Tsarist Empire. For Poland this decision meant a considerable loss of importance, as it could no longer influence the further course of the war. Russia no longer viewed the dual state of Poland-Lithuania as a potential ally, but only as the “forefront” of its empire. The Russian political calculation envisaged bringing the aristocratic republic under control to such an extent that it remained beyond the influence of competing powers. Poland got into an era of sovereignty crisis.

The situation inside the state was just as difficult as the foreign-political situation: in addition to his attempts to assert himself externally, the Saxon elector August II, as the new Polish king, endeavored to reform the republic in his favor and to regain the power of the To expand the king. But within the republic he had neither house power nor sufficient support to push through such an absolutist reform work against the powerful Polish nobility. On the contrary: as soon as he stepped on the scene with his reform efforts, resistance formed among the nobility, which ultimately led to the formation of the Tarnogród Confederation in 1715 . August's coup led to open conflict. Russia seized the opportunity of the civil war and ultimately secured itself longer-term influence with its intervention.

At the end of the Great Northern War in 1721 Poland was one of the official winners, but this victory belies the ever-advancing process of subordination of the republic to the hegemonic interests of neighboring states, caused and promoted by a " coincidence of internal crisis and foreign policy change of constellation" . De iure , Poland was of course not yet a protectorate of Russia, but de facto the loss of sovereignty was clearly noticeable. In the decades that followed, Russia determined Polish politics.

Dependence on foreign countries and resistance within

How great the dependence on the other European powers was was shown by the decision on the succession to the throne after August II died in 1733. It was not only the Szlachta, ie the Polish landed nobility, who should make this decision. In the follow-up discussion, in addition to the neighboring powers, France and Sweden also intervened, trying to place Stanisław Leszczyński on the throne. The three neighboring states of Prussia, Russia and Austria tried to prevent Leszczyński from ascending to the throne and, even before the death of August II, mutually obliged each other to choose their own common candidate ( Löwenwoldesches Traktat or Alliance Treaty of the Three Black Eagles ). A Wettin candidate should be excluded. However, the Polish nobility ignored the decision of the neighboring states and voted for Leszczyński with a majority. However, Russia and Austria were not satisfied with this decision and pushed through a counter-election. Contrary to the agreements and without consulting Prussia, they nominated the son of the late king, Wettin August III. The result was a three-year war of succession to the throne in which the anti-Wettin Confederation of Dzików was defeated and at the end of which Leszczyński abdicated. On the "Pacific Reichstag" in 1736, the Saxon August III bought himself. With the renouncement of own design options finally the royal title and thus ended the interregnum .

The warring confederations would paralyze the republic for almost the entire 18th century. Different parties with different interests faced each other and made it impossible to carry out reforms in a system based on the principle of unanimity . The “liberum veto” made it possible for every single member of the Szlachta to overthrow a previously negotiated compromise through their objection. Through the influence of the neighboring powers, the internal division of the republic intensified, so that, for example, during the entire reign of August III. between 1736 and 1763 not a single Reichstag could be successfully concluded and thus not a law was passed. In the years before, the balance sheet of the Reichstag shows the crippling effect of the unanimity principle: Of the total of 18 Reichstag from 1717 to 1733, eleven were "blown up", two ended without a resolution and only five achieved results.

After the death of August III. In particular, the two Polish noble families Czartoryski and Potocki strove for power. But as with the Interregnum in 1733, the succession to the throne again became a matter of European dimension. Again, it was by no means the Polish aristocratic parties who determined the successor, but the major European powers, especially the large neighboring states. The result of the election of the king was in the interests of Russia, but Prussia also played a decisive role.

The Prussian King Friedrich II tried harder to pursue his interests. As already described in his wills in 1752 and 1768, he intended to create a land connection between Pomerania and East Prussia , his “kingdom”, by purchasing the Polish “ Prussian Royal Share ” . The importance of this acquisition is shown by the frequency with which Frederick repeatedly renewed this wish. In 1771 he wrote: “Polish Prussia would be worth the effort, even if Danzig were not included. Because we would have the Vistula and the free connection with the kingdom, which would be an important thing. "

Poland under Russian hegemony

Since Russia would not have accepted such a gain in power by Prussia without further ado, the Prussian king sought an alliance with the Russian Empress Catherine II. The first opportunity to forge such a Russian-Prussian agreement was the nomination of the new Polish king in April 1764. Prussia accepted the election of the Russian candidate to the Polish throne. Austria remained excluded from this decision, and so Russia almost single-handedly determined the succession to the throne.

Russia's decision about the heir to the throne had long since been made. As early as August 1762, the tsarina assured the former British embassy secretary Stanisław August Poniatowski of the succession to the throne and reached an understanding with the noble family of the Czartoryski about their support. Your choice fell on a person without power and with little political weight. In the eyes of the tsarina, a weak, pro-Russian king offered "the best guarantee for the subordination of the Warsaw court to St. Petersburg's orders ". The fact that Poniatowski was a lover of Catherine II probably played a subordinate role in the decision. Nevertheless, Poniatowski was more than just an embarrassing choice, because the only 32-year-old aspirant to the throne had a comprehensive education, a great talent for languages and had extensive diplomatic and political theoretical knowledge. After his election on 6./7. September 1764 , which went unanimously through the use of considerable bribes and the presence of 20,000 Russian troops , the enthronement finally took place on November 25th. Contrary to tradition, the place of voting was not Krakow, but Warsaw.

Poniatowski, however, turned out to be not as loyal and docile as the Tsarina had hoped. After a short time he began to tackle far-reaching reforms. In order to guarantee the ability to act after the election of the new king, the Reichstag decided on December 20, 1764 to transform itself into a general confederation, which should only exist for the duration of the interregnum. This meant that future diets would be exempted from the “liberum veto” and majority decisions (pluralis votorum) were sufficient to pass resolutions. In this way the Polish state was strengthened. Catherine II did not want to let go of the advantages of the permanent blockade of political life in Poland, the so-called “Polish anarchy”, and looked for ways to prevent a functioning and reformable system. To this end, she had some pro-Russian nobles mobilized and allied them with Orthodox and Protestant dissidents who had suffered from discrimination since the Counter-Reformation . In 1767, Orthodox aristocrats formed the Confederation of Slutsk and Protestants formed the Confederation of Thorn . The Radom Confederation emerged as the Catholic response to these two confederations . At the end of the conflict there was a new Polish-Russian treaty, which was forcibly approved by the Reichstag on February 24, 1768. This so-called "Eternal Treaty" contained the manifestation of the unanimity principle, a Russian guarantee for the territorial integrity and for the political "sovereignty" of Poland, as well as religious tolerance and legal and political equality for the dissidents in the Reichstag. However, this contract did not last long.

The first division in 1772

Prussian-Russian agreements

Poniatowski's attempts at reform presented Tsarina Katharina with a dilemma: if she wanted to stop them permanently, she had to get involved in the military. But that would provoke the other two great powers bordering on Poland, who, according to the doctrine of the balance of power, would not accept a clear Russian hegemony over Poland. As the historian Norman Davies writes, in order to persuade them to stand still, territorial concessions at Poland's expense were offered as “bribes”. The year 1768 gave a special boost to the First Partition of Poland. The Prussian-Russian alliance took on more concrete forms. Decisive factors for this were the domestic Polish difficulties as well as the foreign policy conflicts with which Russia was confronted: Within the Kingdom of Poland , the resentment of the Polish nobility about the Russian protectorate rule and the open disregard for sovereignty increased. Just a few days after the "Eternal Treaty" was passed, the anti-Russian Confederation of Bar was founded on February 29, 1768, and was supported by Austria and France. Under the slogan of defense of “faith and freedom”, Catholic and Polish republican men came together to force the withdrawal of the “Eternal Treaty” and to fight against Russian supremacy and the pro-Russian King Poniatowski. Russian troops then invaded Poland again. The will to reform intensified as Russia increased its reprisals .

Only a few months later in the fall also a declaration of war the Ottoman Empire to the Russian Tsarist empire (see Russo-Turkish War 1768-1774 ), triggered by the internal unrest in Poland. The Ottoman Empire had long rejected Russian influence in Poland and used the uprising of the nobility to show solidarity with the rebels. Russia was now in a two-front war .

The Prussian calculation , according to which the Hohenzollerns appeared as helpers of Russia in order to get a free hand in the annexation of Polish Prussia, seemed to work out. Under the pretext of containing the spread of the plague , King Friedrich had a border cordon drawn across western Poland. When his brother Heinrich was in St. Petersburg in 1770/1771, the tsarina once brought the conversation to the Spis towns , which Austria had annexed in the summer of 1769. Katharina and her Minister of War, Sachar Tschernyschow , jokingly asked why Prussia is not following this Austrian example: “But why not take away the Principality of Warmia ? After all, everyone has to have something? ”Prussia saw the chance to support Russia in the war against the Turks in return for Russian consent for the annexation. Frederick II had his offer sounded out in Petersburg. Catherine II hesitated, however, in view of the Polish-Russian treaty of March 1768, which guaranteed the territorial integrity of Poland. However, under the increasing pressure of the Confederate troops, the Tsarina finally consented and paved the way for the First Partition of Poland.

Approval despite rejection

Although Russia and Austria initially rejected an annexation of Polish territory in principle, the idea of division moved more and more into the center of considerations. The decisive leitmotif was the will to maintain a balance of power and politics while preserving the “aristocratic anarchy” that manifested itself in and around the Liberum Veto in the Polish-Lithuanian aristocratic republic.

After Russia went on the offensive in the conflict with the Ottoman Empire in 1772 and a Russian expansion in southeastern Europe became foreseeable, both the Hohenzollern and the Habsburgs felt threatened by the possible growth of the Tsarist Empire. Their rejection of such a unilateral gain of territory and the associated increase in Russian power gave rise to plans for all-round territorial compensation. Frederick II now saw the opportunity to implement his agrandissement plans and stepped up his diplomatic efforts. He referred to a proposal that had already been explored in 1769, the so-called "Lynar Project", and saw it as an ideal way out to avoid a shift in the balance of power: Russia should renounce the occupation of the principalities of Moldova and Wallachia , which was primarily in Austria's interest. Since Russia would not agree to this without a corresponding consideration, the Tsarist Empire should be offered a territorial equivalent in the east of the Kingdom of Poland as a compromise. At the same time Prussia was to receive the areas on the Baltic Sea that it was striving for. In order for Austria to agree to such a plan, the Galician parts of Poland were to be added to the Habsburg Monarchy .

While Frederick's policy thus continues on the rounding of the West Prussian aimed territory, the chance offered Austria a small compensation for the loss of Silesia (see. In 1740 Silesian Wars ). But Maria Theresa , according to her own statement, had “moral concerns” and was reluctant to allow her compensation claims to come into effect at the expense of an “innocent third party” and, moreover, a Catholic state. It was precisely the Habsburg Monarchy that prejudiced such a division as early as autumn 1770 with the “re-corporation” of 13 towns or market towns and 275 villages in the Spis County . These towns were ceded to Poland by the Kingdom of Hungary in 1412 and were not redeemed later. According to the historian Georg Holmsten , this military action had initiated the actual partition action. While the head of the House of Habsburg-Lothringen was still consulting with her son Joseph II , who sympathized with a partition, and the State Chancellor Wenzel Anton Kaunitz , Prussia and Russia concluded a separate partition agreement on February 17, 1772, thereby putting Austria under pressure . Ultimately, the monarch's worries about a postponement or even a loss of power and influence and the risk of opposition to the two powers outweighed it. The Polish territory should not be divided among these alone, which is why Austria joined the partition treaty. Although the Habsburg Monarchy hesitated in this case, the State Chancellor von Kaunitz had already made attempts at the end of the 1760s to conclude an exchange deal with Prussia, in which Austria would get Silesia back and in return support Prussia in its plans to consolidate the Polish-Prussia. Austria was not only a silent beneficiary, because both Prussia and Austria were actively involved in the division. The Russian plans suited them in view of the plans that had been circulating years earlier and offered a welcome opportunity to implement their own interests.

On August 5, 1772, the partition treaty between Prussia, Russia and Austria was finally signed. The "Petersburg Treaty" was declared as a "measure" for the "pacification" of Poland and meant for Poland a loss of over a third of its population and over a quarter of its previous territory, including the economically important access to the Baltic Sea with the Vistula estuary. Prussia got what it had been striving for for so long: With the exception of the cities of Danzig and Thorn , the entire area of the Prussian Royal Part and the so-called Netzedistrikt became part of the Hohenzollern monarchy. It received the smallest proportion according to size and population. Strategically, however, it acquired the most important territory and thus benefited significantly from the First Partition of Poland.

“An important desideratum of territorial, state and dynastic prestige was fulfilled. In future, West Prussia should form the indispensable 'tendon' of Prussia in the north-east, both strategically and economically. "

In the future, the king was allowed to call himself “King of Prussia” and not just “King in Prussia”. Russia renounced the Danube principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, but was granted the Polish-Livonia and the Belarusian regions up to the Daugava . Austria secured the Galician territory with the city of Lemberg as the center with parts of Lesser Poland .

For the Kingdom of Poland, the largest country in Europe after Russia, the fragmentation of its territory meant a turning point . Poland became the plaything of its neighbors. The alliance of the three black eagles saw the kingdom as a bargaining chip. Frederick II described the partition of Poland in 1779 as an outstanding success in novel crisis management.

The second division in 1793

Despite the territorial gains of the First Division, those responsible in Prussia were not entirely satisfied with the result. Although the negotiators tried hard to do so, they did not succeed in incorporating the cities of Danzig and Thorn into Prussian territory , as had already been assured by the Polish side in the Polish-Prussian alliance , which is why the Hohenzollern monarchy tried to further consolidate them. Maria Theresa, too, who initially hesitated to split up, suddenly expressed further interest. She was of the opinion that the areas acquired by the division were inadequate in view of the loss of Silesia and the comparatively higher strategic importance of the areas acquired by Prussia.

Domestic disputes

The domestic political situation in Poland was initially still characterized by the rivalry between the king and his supporters on the one hand and the opposition magnates on the other. Russia sought to maintain this rivalry while securing its role as a protectorate power. Poland's weakness should persist. The aim was therefore to keep the opposing aristocratic parties in a stalemate and to maintain the balance of power, whereby the side loyal to the king, especially the Czartoryskis, should have a slight preponderance. The diets of 1773 and 1776 were supposed to institutionalize this and adopt reforms to strengthen the king. However, the aristocratic opposition already refused to strengthen the executive and expand the prerogatives of the king, and thus their resistance to the reforms increased in view of the fact that the resolutions were the result of Poniatowski's cooperation with Russia. The main goal of the magnates was now to reverse the Reichstag resolutions of 1773 and 1776. However, this would only have been made possible by the formation of a Confederate Diet, on which resolutions could be passed with a simple majority without being overturned by a liberum veto . However, such a Reichstag met with considerable resistance from the protector Russia. It was therefore impossible to change the constitution. The magnate opposition was neither able to obtain a revision of the resolutions of 1773 and 1776, nor was Poniatowski possible to push through further reforms, especially since Russia supported the last reforms to strengthen the king, but rejected any action that meant a departure from the status quo. Although encouraged by Catherine II, the Polish king continued to pursue measures to reform and consolidate the Polish state, and for this purpose also sought the formation of a Confederate Reichstag. In 1788 Poniatowski had the opportunity to do so when the Russian troops were involved in a two-front war against Sweden and Turkey (cf. Russo-Austrian Turkish War 1787–1792 and Russo-Swedish War 1788–1790 ), which is why Russia's military resources are less opposed Poles could judge.

The strong reform spirit that was to shape this long-awaited Reichstag revealed the beginnings of a new capacity for action for the aristocratic republic, which could not be in the interests of the Russian tsarina. Klaus Zernack described this situation as the "shock effect of the first division", which "quickly changed into a spirit of optimism of its own". The changes in the administration and in the political system of the aristocratic republic aimed for by Stanisław August Poniatowski were intended to lift the political paralysis of the electoral monarchy, change the country socially, socially and economically and lead to a modern state and state administration. However, Russia and Prussia viewed this development with suspicion. Poniatowski, initially supported by the Tsarina, suddenly turned out to be too reform-minded, especially for Russian tastes, so that Catherine II tried to put an end to the modernization that was being sought. For her part, she therefore reversed the signs and now openly supported the anti-reform magnate opposition.

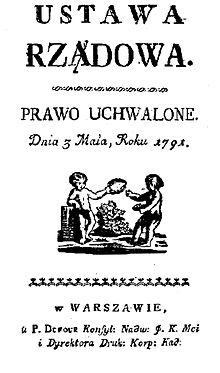

Constitution of May 3, 1791

In view of its negative attitude towards the reforms, Prussia acted contradictingly: After the pro-Prussian sympathies in Poland had quickly come to an end after the First Partition, the relationship between the two states improved. On March 29, 1790, the rapprochements even resulted in a Prussian-Polish alliance. After a few friendly declarations and positive signals, the Poles felt safe and independent from Prussia and even saw Friedrich Wilhelm II as their protector. The alliance should therefore, so the hope of Poland, secure the reforms, especially in foreign policy. The role of Prussia in the First Partition seemed forgotten. But his policy was not as unselfish as hoped, because the following also applied to Prussia: the "aristocratic anarchy" and the power vacuum were quite intentional, which is why it was in both Prussian and Russian interests to counteract the aforementioned reform efforts. The efforts were unsuccessful, however. The most important innovations included the abolition of the aristocratic privilege of tax exemption and the establishment of a standing crown army with 100,000 men as well as the realignment of citizenship law.

Under the constantly increasing pressure from neighboring states, combined with the fear of intervention, the king was forced to implement his further reform projects as quickly as possible. In a session of the Reichstag on May 3, 1791, Poniatowski presented the MPs with a draft for a new Polish constitution , which the Reichstag approved after just seven hours of deliberation. At the end of the four-year Sejm , the first modern constitution in Europe was created.

The constitution, known as the “government statute”, consisted of only eleven articles, which, however, brought about far-reaching changes. Influenced by the works of Rousseau and Montesquieu , the principles of popular sovereignty and the separation of powers were established. The constitution provided for the introduction of the majority principle as opposed to liberum veto , ministerial responsibility and a strengthening of the state executive, especially the king. Furthermore, state protection clauses for the peasant people were passed, which should protect the mass of serf peasants from arbitrariness and squeezing. The townspeople were also guaranteed civil rights. The Catholicism was declared the dominant religion, the freedom of worship of other faiths but legitimized.

In order to ensure the ability of the aristocratic republic to act even after the death of a king and to prevent an interregnum, the parliamentarians decided to abolish the elective monarchy and introduce a hereditary dynasty - with the Wettins as the new ruling family. This made Poland a parliamentary - constitutional monarchy . However, the will to compromise prevented even more far-reaching reforms: the planned abolition of serfdom and the introduction of basic personal rights for the peasantry as well failed due to the resistance of the conservatives.

Influenced by the works of the great state theorists , shaped by the climate of the Enlightenment and its discourses, and impressed by the events of the French Revolution and the ideas of the Jacobins , Poland was to become one of the most modern states at the end of the 18th century. Although the MPs tried to implement the new constitutional principles after the constitution was passed, what they had achieved did not last long.

Reactions from neighboring countries

The constitutional affront soon prompted neighboring states to act. "Catherine II of Russia was furious about the adoption of the constitution and raged that this document was a concoction, worse than the French National Assembly could imagine, and also capable of wresting Poland from the Russian apron." Russia now supported them Forces in Poland who turned against the May constitution and had also fought against the Reichstag resolutions of 1773 and 1776. With the support of the Tsarina, the Targowica Confederation took vehement action against the king and his supporters. When the Russian-Ottoman conflict finally came to an end in January 1792, military forces were released again, which enabled Catherine II to intervene (see Russian-Polish War 1792 ). One year after the end of the four-year Sejm, Russian troops entered Poland. The Polish army was defeated, and the Kingdom of Prussia unilaterally left the Polish-Prussian Defensive Alliance of 1790, which was directed against Russia, and Poniatowski had to submit to the Tsarina. The May 3 Constitution was repealed while Russia regained its role as a regulatory power. In view of the events, Catherine II was now open to a further partition of Poland:

"Poland became unbearable for its neighbors at the moment when it regenerated itself from its powerlessness to such an extent that it was able to become active in foreign policy on its own."

Prussia also recognized the opportunity to take advantage of this situation in order to get possession of the coveted cities of Danzig and Thorn. However, Russia, which alone suppressed the reform efforts in Poland, was little inclined to comply with Prussia's request. Prussia therefore linked the Polish with the French question and threatened to withdraw from the European coalition war against revolutionary France if it was not appropriately compensated. Given the choice, Catherine II decided after long hesitation to maintain the alliance and agreed to a renewed division of Polish territories among Prussia, as “reimbursement of the costs of the war, contre les rebelles français ”, and the tsarist empire. However, at the request of the Tsarina, Austria was left out of this act of partition. In the partition treaty of January 23, 1793, Prussia received control over Danzig and Thorn as well as Greater Poland and parts of Mazovia , which were combined to form the new province of South Prussia . The Russian territory expanded to include all of Belarus as well as large areas of Lithuania and Ukraine . In order to legalize this act, the members of the Reichstag in Grodno were pressured to agree to the division of their country only a few months later, threatened with weapons and heavily bribed by the partitioning powers.

The third division in 1795

After the first partition of Poland it was still in the interests of the neighboring states to stabilize the kingdom again and then to establish it as a weak and incapable remainder of the state, but the signs changed after the second partition of 1793. The question of the survival of the remaining Polish state was not asked. Neither Prussia nor Russia wanted the kingdom to continue to exist within the new borders. The Second Partition of Poland mobilized the kingdom's resistance forces. Not only the nobility and the clergy resisted the occupying powers. The bourgeois intellectual forces and the peasant social revolutionary population also joined the resistance. Within a few months, the anti-Russian opposition pulled large parts of the population on their side. At the head of this counter-movement sat Tadeusz Kościuszko , who had already fought on the side of George Washington in the American War of Independence and who returned to Krakow in 1794. In the same year the resistance culminated in the Kościuszko uprising named after him .

The clashes between the rebels and the partitioning powers lasted for months. Again and again the resistance forces were able to record successes. Ultimately, however, the occupying forces prevailed and on October 10, 1794, Russian troops captured Kościuszko, seriously wounded. In the eyes of the neighboring powers, the insurgents forfeited another right to exist for a Polish state.

"The fact that the Poles dared to determine their own national fate brought the Polish state the death sentence."

Now Russia strove to divide up and dissolve the rest of the state, and for this purpose first sought an understanding with Austria. If Prussia had previously been the driving force, it now had to put its claims aside, as both Petersburg and Vienna were of the opinion that Prussia had so far benefited most from the two previous partitions. On January 3, 1795, Catherine II and the Habsburg Emperor Franz II signed the partition treaty, which Prussia joined on October 24. Accordingly, the three states divided the rest of Poland along the rivers Memel , Bug and Pilica . Russia moved further west and occupied all areas east of Bug and Memel, Lithuania, and all of Courland and Zemgale . The Habsburg sphere of influence expanded to the north to include the important cities of Lublin , Radom , Sandomierz and especially Krakow . Prussia, however, the remaining areas was west of the bow and Memel with Warsaw , which then form part of the new province of East Prussia were, and the north to Krakow New Silesia . After Stanisław August abdicated on November 25, 1795, the partitioning powers declared the Kingdom of Poland to be extinguished two years after the third and last partition of Poland.

“Poland was seen as an available and welcome 'fund', which made it possible to satisfy the territorial profit-seeking of the three powers in the simplest possible way and with the help of which the political differences between Prussia, Russia and Austria were jointly complicit To transform the burdens of an innocent fourth and thus "harmonize" for a while. "

The Poles did not accept the lack of statehood. As part of the preparation of the Polish Legion in the French army in 1797 was the fight song " Still, Poland is not lost ," which in the following century accompanied the various uprisings and finally the national anthem of the wake of the First World War from 1914 to 1918 formed Second Polish Republic was.

Statistics of the divisions

Territorial Statistics

As a result of the partitions, one of the largest states in Europe was wiped off the map. The information on the size and number of inhabitants fluctuates greatly, which is why it is difficult to quantify the losses of the Polish state or the profits of the partitioning powers. Based on the information provided by Roos, Russia benefited most from the partitions in quantitative terms: with 62.8 percent of the territory, the tsarist empire received around three times as much as Prussia with 18.7 percent or Austria with 18.5 percent. Almost every second inhabitant of Poland, around 47.3 percent in total, lived in Russian territories after the partition. Austria had the smallest increase in area, but the newly created Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria was a densely populated region, which is why, at 31.5 percent, almost a third of the Polish population became part of the Habsburg monarchy. Prussia was given a slightly larger area than Austria, although only 21.2 percent of the population was inhabited.

| division | Prussia | Russia | Austria | total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km² | Population (million) | km² | Population (million) | km² | Population (million) | km² | Population (million) | |

| 1st division | 34,900 | 0.356 | 84,000 | 1.256 | 83,900 | 2,669 | 202,800 | 4.281 |

| 2nd division | 58,400 | 1.136 | 228,600 | 3.056 | - | - | 287,000 | 4,192 |

| 3rd division | 43,000 | 1.042 | 146,000 | 1,338 | 51,100 | 1.098 | 240,100 | 3.478 |

| total | 136,300 | 2.534 | 458,600 | 5,650 | 135,000 | 3.767 | 729,900 | 11,951 |

Ethnic composition of the subdivisions

With regard to the ethnic composition, no precise information can be given, as there were no population statistics. What is certain, however, is that the actual Poles made up only a small minority in the areas that came to Russia. Most of the local population consisted of Greek Orthodox Ukrainians and Belarusians, as well as Catholic Lithuanians. In many cities of the Russian partition, such as Vilnius (Polish: Wilno) , Hrodna (Polish: Grodno) , Minsk or Homel , there was a numerically and culturally significant Polish element. There was also a large Jewish population. The “liberation” of the Orthodox East Slavic peoples from Polish-Catholic sovereignty was later brought into the field by the national Russian historiography to justify the territorial annexations. In the areas that came to Prussia there was a numerically significant German population in Warmia , Pomerellen and in the western outskirts of the new province of South Prussia . The bourgeoisie of the cities of West Prussia, especially that of the old Hanseatic cities of Danzig and Thorn, had always been predominantly German-speaking. The annexation of the Polish territories multiplied the Jewish population of Prussia, Austria and Russia . Even when Prussia renounced about half of the territories it had acquired in the partitions in favor of Russia at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, more than half of all Prussian Jews still lived in the formerly Polish areas of Pomerellen and Posen . When, after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, a Kingdom of Poland was re-established in personal union with the Russian Empire (“ Congress Poland ”), it comprised only part of the former Prussian and Austrian division. The territories that came to Russia remained with it. In 1815, 82% of the former Polish-Lithuanian territories fell to Russia (including Congress Poland), 8% to Prussia and 10% to Austria.

research

In German historiography, the partitions of Poland-Lithuania have so far been a marginal topic. Probably the most relevant overview work "The Partitions of Poland" by Michael G. Müller appeared in 1984 and is no longer being reissued. Their historical importance is by no means insignificant. Müller already states: “It is common not only for Polish, but also for French and Anglo-Saxon historians to classify the partitions of Poland among the [...] epoch-making events of early modern Europe, that is, to weight them similarly to the Thirty Years War or the French Revolution. ”Nevertheless, 30 years after Müller's statement, it is still true that“ measured by its objective being affected ”, German historical studies“ took too little interest ”in the partition of Poland. In spite of new research efforts (especially at the universities of Trier and Giessen ), the topic is still in some cases a desideratum of German research. The most recent research results are presented in the anthology The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania from 2013. As expected, the topic is much more widely researched in Polish literature.

In contrast, the sources are much better. The most important holdings can be found in the Secret State Archive of Prussian Cultural Heritage (GStA PK) in Berlin-Dahlem and in the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych (AGAD) in Warsaw . An edited collection of sources is the Novum Corpus Constitutionum (NCC), which can be accessed online and primarily contains public announcements.

The partitions of Poland are well documented on maps . As a result of the extensive territorial changes, there was a great demand for current maps. In the German-speaking area, for example, Johannes Walch's publishing house issued a map of Poland, which he had to adapt to the political situation several times. However, an even approximately complete bibliography of all maps of the Polish partitions is still missing.

Remnants of boundary signs

In the town of Thorn and its vicinity you can still see the remains of the former Prussian-Russian border. It is a 3–4 m wide depression with two high walls on either side.

The place near Myslowitz is called Dreikaisereck , where the borders of Prussia, Austria and Russia collided from 1846 to 1915.

In a village called Prehoryłe in the Hrubieszów district , about 100 m from the Ukrainian border, there is a wayside cross, the lower, long arm of which was an old Austrian border post. In the lower area you can see the word “Teschen”, the name of today's town of Cieszyn , where the border posts were made. The Bug River , which today forms the Polish-Ukrainian border, was the border river between Austria and Russia after the third division of Poland.

See also

literature

- Karl Otmar Freiherr von Aretin : Exchange, division and country chatters as consequences of the equilibrium system of the major European powers. The Polish partitions as a European fate . In: Klaus Zernack (Ed.): Poland and the Polish Question in the History of the Hohenzollern Monarchy 1701–1871 . (= Individual publications of the Historical Commission in Berlin . Volume 33). Colloquium-Verlag, Berlin 1982, pp. 53-68, ISBN 3-7678-0561-8 .

- Martin Broszat : 200 years of German politics in Poland. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1986 (4th ed.), ISBN 3-518-36574-6 .

- Tadeusz Cegielski: "Germany and Poland Policy" in the period 1740–1792 , in: Klaus Zernack (Ed.): Poland and the Polish Question in the History of the Hohenzollern Monarchy 1701–1871 (= individual publications by the Historical Commission in Berlin . Volume 33) . Colloquium-Verlag, Berlin 1982, pp. 21-27, ISBN 3-7678-0561-8 .

- Tadeusz Cegielski: The old empire and the first partition of Poland 1768–1774. Steiner, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-515-04139-7 .

- ACA Friederich: Historical-geographical representation of old and new Poland. With 2 cards. Berlin 1839 ( books.google.de ).

- Horst Jablonowski: The first partition of Poland , in: Contributions to the history of West Prussia , Vol. 2 (1969), pp. 47-80.

- Rudolf Jaworski , Christian Lübke , Michael G. Müller : A little history of Poland. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-518-12179-0 .

- Hans Lemberg : Poland between Russia, Prussia and Austria in the 18th century , in: Friedhelm Berthold Kaiser, Bernhard Stasiewski (Hrsg.): The first Polish partition 1772 (= Studies on Germanism in the East . Volume 10). Böhlau, Cologne 1974, pp. 29-48, ISBN 3-412-02074-5 .

- Jerzy Lukowski: The partitions of Poland 1772, 1793, 1795. Longman, London 1999, ISBN 0-582-29275-1 .

- Jerzy Michalski: Poland and Prussia in the epoch of partitions , in: Klaus Zernack (ed.): Poland and the Polish question in the history of the Hohenzollern monarchy 1701–1871 . (= Individual publications of the Historical Commission in Berlin . Volume 33). Colloquium-Verlag, Berlin 1982, pp. 35-52, ISBN 3-7678-0561-8 .

- Erhard Moritz: Prussia and the Kościuszko uprising in 1794. On Prussian Poland policy during the French Revolution . (= Series of publications by the Institute for General History at the Humboldt University in Berlin . Volume 11). Berlin 1968.

- Michael G. Müller : The partitions of Poland 1772, 1793, 1795. Beck, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-406-30277-7 .

- Gotthold Rhode : The Polish aristocratic republic around the middle of the 18th century , in: Friedhelm Berthold Kaiser, Bernhard Stasiewski (ed.): The first Polish division in 1772 (= Studies on Germanism in the East, Vol. 10). Böhlau, Cologne 1974, ISBN 3-412-02074-5 , pp. 1–26.

- Hans Roos: Poland from 1668 to 1795 , in: Theodor Schieder , Fritz Wagner (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Europäische Geschichte . Volume 4. Europe in the Age of Absolutism and the Enlightenment. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1968, pp. 690-752.

- Anja Ströbel: The Polish partitions. An analytical comparison , in: Riccardo Altieri, Frank Jacob (Ed.): Spielball der Mächte. Contributions to Polish history . minifanal, Bonn 2014, ISBN 978-3-95421-050-3 , pp. 14-36.

- Hugo Weczerka : Putzger wall maps . Poland in the 20th century. The partition of Poland 1772–1795 , vol. 116, Velhagen & Klasing, Bielefeld 1961.

- Klaus Zernack : Poland in the history of Prussia , in: Otto Büsch (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Prussischen Geschichte. Volume II: The 19th Century and Major Topics in the History of Prussia. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, pp. 423-431.

- Agnieszka Pufelska: The better neighbor? The Polish image of Prussia between politics and cultural transfer (1765–1795) . Walter de Gruyter, Oldenbourg, Berlin / Boston 2017. ISBN 978-3-11-051833-7 .

Web links

- Bibliography. LitDok East Central Europe (Herder Institute Marburg)

- The third partition of Poland . deutsche-und-polen.de, to the series Germans and Poles of the RBB

- Agnieszka Barbara Nance: Nation without a State: Imagining Poland in the Nineteenth Century . (PDF; 7.2 MB), Doctor of Philosophy dissertation, University of Texas at Austin , 2004.

- deutschlandfunknova.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ The term Polish partitions is rejected in scientific discourse; the partitions of Poland always refer to the entire state of Poland-Lithuania.

- ↑ Cf. Rudolf Jaworski, Christian Lübke, Michael G. Müller: Eine kleine Geschichte Polens , Frankfurt a. M. 2000, p. 167.

- ↑ For periodization cf. Müller: The partitions of Poland , p. 12 f.

- ↑ Due to the death of the founder of the Rzeczpospolita, Sigismund II. August , a hereditary monarchy until 1572.

- ↑ See Hans Lemberg: Poland between Russia, Prussia and Austria in the 18th century , in: Friedhelm Berthold Kaiser, Bernhard Stasiewski (Ed.): The first Polish division 1772, Cologne 1974, p. 36 f., Or Müller: Die Partitions of Poland , pp. 15–18.

- ↑ Müller: The Partitions of Poland , p. 14.

- ↑ See Müller: The Partitions of Poland , p. 17.

- ↑ Cf. Jaworski, Müller, Lübke: Eine kleine Geschichte Polens , p. 178 f., And Müller: Die Teilungen Poland , pp. 18-20.

- ↑ See Jaworski, Müller, Lübke: Eine kleine Geschichte Polens , p. 181.

- ↑ See Meisner: Judicial System and Justice , p. 314.

- ↑ Cf. Martin Broszat: 200 Years of German Policies , Frankfurt a. M. 1972, p. 45.

- ↑ Quoted in: Broszat: 200 years of German Poland policy , p. 47.

- ↑ a b cf. Hans Roos: Poland from 1668 to 1795 , in: Theodor Schieder, Fritz Wagner (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Europäische Geschichte. Vol. 4: Europe in the Age of Absolutism and Enlightenment , Stuttgart 1968, p. 740.

- ↑ Jaworski, Müller, Lübke: Eine kleine Geschichte Polens , p. 185.

- ↑ Cf. Roos: Poland from 1668 to 1795 , p. 741.

- ↑ See Andrea Schmidt-Rösler: Poland. From the Middle Ages to the Present , Regensburg 1996, p. 53.

- ↑ Norman Davies: In the Heart of Europe. History of Poland . CH Beck, Munich 2006, p. 280.

- ↑ Erhard Moritz: Prussia and the Kościuszko uprising 1794. On Prussian Poland policy in the time of the French Revolution . Berlin 1968, p. 17 f.

- ↑ Heinrich's letter to his brother of January 8, 1771, quoted by Gustav Berthold Volz (Ed.): The works of Frederick the Great in German translation , Vol. 5: Memories from the Peace of Hubertusburg to the end of the division of Poland . Reimar Hobbing, Berlin 1913, p. 27, note 3 ( uni-trier.de , accessed April 1, 2012).

- ↑ Cf. Lemberg: Poland between Russia, Prussia and Austria in the 18th century , p. 42.

- ↑ See Müller: Die Teilteilens Poland , p. 36.

- ↑ Cf. Broszat: 200 years of German Poland policy , p. 46 f.

- ↑ Cf. Lemberg: Poland between Russia, Prussia and Austria in the 18th century , p. 42 and Broszat: 200 years of German Poland policy , p. 48.

- ^ Friedrich von Raumer : Poland's downfall . Brockhaus, Second Edition, Leipzig 1832, p. 50 (= historical paperback , third volume, Leipzig 1832, p. 446.)

- ↑ ACA Friederich: Historical-geographical representation of old and new Poland . Berlin 1839, pp. 418-422.

- ^ Georg Holmsten: Friedrich II. In self-testimonies and picture documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1979, p. 146.

- ^ Broszat: 200 Years of German Policies , p. 49.

- ^ For the takeover of the new acquisition, see Walther Hubatsch: The takeover of West Prussia and the network district by Prussia in 1772 ; in: Friedhelm Berthold Kaiser, Bernhard Stasiewski (eds.): The first Polish partition 1772 , Cologne 1974, pp. 75–95.

- ↑ Cf. Müller: Die Teilteilens Poland , p. 39.

- ↑ Cf. Müller: Die Teilteilens Poland , p. 40 f.

- ^ Nevertheless, Daniel Stone dedicates his own monograph to this period: Polish Politics and National Reform 1775–1788 , New York 1976.

- ↑ Klaus Zernack: Poland in the history of Prussia , in: Otto Büsch (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Prussischen Geschichte . Vol. II: The 19th Century and Great Issues in the History of Prussia , Berlin, New York 1992, p. 424.

- ↑ See Michalski: Poland and Prussia in the epoch of partitions , p. 50.

- ↑ Cf. Jan Kusber: From Project to Myth - The Polish May Constitution 1791 , in: Journal for History Science, 8/2004, p. 685.

- ↑ Further to this: Kusber: From Project to Myth - The Polish May Constitution 1791. P. 685–699. In addition to the content of the constitution, Kusber also presents the elements of dealing with its legacy and takes a look at its current status in the Eastern European context. Also continuing: Helmut Reinalter (Ed.): The Polish constitution of May 3, 1791 against the background of the European Enlightenment. Frankfurt am Main 1997 and Stanislaw Grodziski: The Constitution of May 3, 1791 - the first Polish constitution. In: From politics and contemporary history , Vol. 30–31 / 1987, pp. 40–46.

- ↑ See Müller: Die Teilteilens Poland , p. 23; Broszat: 200 Years of German Policies , p. 56; Michalski: Poland and Prussia in the epoch of partitions , p. 44. Jaworski, Müller, Lübke: Eine kleine Geschichte Polens , p. 189. Roos: Poland from 1668 to 1795 , p. 750.

- ↑ Jan Kusber : From Project to Myth - The Polish May Constitution 1791 , p. 686.

- ↑ Poland between Russia, Prussia and Austria in the 18th century , Cologne 1974, p. 46.

- ^ Hans Roos: Poland from 1668 to 1795. In: Theodor Schieder, Fritz Wagner (Ed.): Handbuch der Europäische Geschichte. Volume 4: Europe in the Age of Absolutism and the Enlightenment. Stuttgart 1968, pp. 690-752, here p. 750.

- ↑ On the importance of the coalition war against France as a diplomatic means of pressure, see: Erhard Moritz: Prussia and the Kościuszko uprising 1794. On Prussian Poland policy during the French Revolution , pp. 28–32.

- ↑ Cf. Broszat: 200 years of German Poland policy , p. 61 f.

- ^ Gotthold Rhode: History of Poland. An overview . 3rd edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft (WBG), Darmstadt 1980, p. 325.

- ↑ For more information see Zbigniew Góralski: The border demarcations in Poland after the third division (1795–1797) . In: Yearbooks for the History of Eastern Europe , Volume 19/1971, pp. 212-238.

- ↑ Cf. Roos: Poland from 1668 to 1795 , pp. 746–751. Roos points out that the digits he used were determined and calculated by himself in various archives.

- ^ Friedrich Luckwaldt: Germany, Russia, Poland. Kafemann, Danzig 1929, p. 12; and Joachim Rogall (ed.): Land of the great rivers. From Poland to Lithuania. ( German History in Eastern Europe , Volume 6) Siedler, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-88680-204-3 , p. 193.

- ^ Müller: The Partitions of Poland , Munich 1984, p. 7.

- ^ Müller: The Partitions of Poland , Munich 1984, p. 11.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg , Andreas Gestrich , Helga Schnabel-Schüle (ed.): The partitions of Poland-Lithuania. Inclusion and exclusion mechanisms - formation of tradition - levels of comparison , Osnabrück 2013.

- ↑ Kazimierz Kozica, Michael Ritter: The "Charte des Koenigreichs Polen" by Johannes Walch. In: Cartographica Helvetica , Heft 36, 2007, pp. 3–10 full text .