Geneva Conventions

The Geneva Conventions , also known as the Geneva Conventions , are intergovernmental agreements and an essential component of international humanitarian law . In the event of a war or an international or non-international armed conflict, they contain rules for the protection of persons who do not or no longer take part in the fighting. The provisions of the four conventions of 1949 concern the wounded and sick of the armed forces in the field (Geneva Convention I), the wounded, sick and shipwrecked of the armed forces at sea (Geneva Convention II), prisoners of war (Geneva Convention III) and civilians in wartime (Geneva Convention IV).

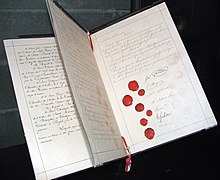

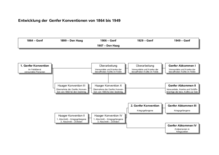

On August 22nd, 1864, twelve states adopted the first Geneva Convention “Relieving the Lot of Military Personnel Wounded in the Field Service” in the town hall of Geneva . The second agreement from a chronological point of view was the current Third Geneva Convention, which was adopted in 1929. Together with two new agreements, both conventions were revised in 1949. These versions came into force one year later and represent the currently valid versions. They were supplemented in 1977 by two additional protocols which for the first time integrated rules for dealing with combatants and for detailed requirements for internal conflicts in the context of the Geneva Conventions. In 2005, a third additional protocol was adopted to introduce an additional trademark .

Switzerland is the depositary state of the Geneva Conventions ; only states can become contracting parties. At present, 196 countries have acceded to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and 174 and 168 countries respectively to the first two additional protocols of 1977, 72 countries have ratified the third additional protocol of 2005. The only control body explicitly named in the Geneva Conventions is the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The Geneva Conventions are unilaterally binding law for the signatory states . The law agreed therein is applicable to everyone.

history

Beginning in 1864

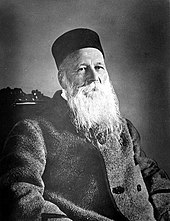

The development of the Geneva Conventions is closely linked to the history of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The Geneva Conventions, like the ICRC itself, have their origins in the experiences of the Geneva businessman Henry Dunant after the Battle of Solferino on June 24, 1859, which he published in 1862 in a book entitled A Memory of Solferino . In addition to the description of his experiences, the book contained suggestions for the establishment of voluntary aid societies and for the protection and care of the wounded and sick during the war.

The implementation of Dunant's proposals led in February 1863 to the establishment of the International Committee of Aid Societies for the Care of the Wound , which has been called the International Committee of the Red Cross since 1876 . As part of these efforts, the first Geneva Convention was passed on August 22, 1864 at a diplomatic conference.

Twelve European countries were involved: Baden , Belgium , Denmark , France , Hesse , Italy , the Netherlands , Portugal , Prussia , Switzerland , Spain and Württemberg . In December of the same year, the Scandinavian countries Norway and Sweden were added. Article 7 of this convention defined a sign to identify the persons and institutions under their protection, which became the eponymous symbol of the newly created movement: the red cross on a white background. The Geneva lawyer Gustave Moynier , who in 1863, as chairman of the Geneva Public Benefit Society, initiated the establishment of the International Committee, played a major role in drafting the convention .

Why the convention was passed in a relatively short time after the book was published and why the convention spread rapidly in the following years is historically incomprehensible. It can be assumed that at that time in many countries among politicians and military officials the opinion was widespread that the near future would bring a series of inevitable wars. This position was based on the ius ad bellum (“right to wage war”), which was generally accepted at the time , which viewed war as a legitimate means of resolving interstate conflicts. The idea behind the acceptance of Dunant's proposals may therefore have been that the inevitable should at least be regulated and “humanized”. Second, the very direct and detailed description in Dunant's book may have for the first time brought before some leading figures in Europe the reality of war. Thirdly, in the decades following the founding of the International Committee and the adoption of the Convention, a number of nation states in Europe emerged or consolidated. The resulting national Red Cross societies also created identity in this context. They often achieved a broad membership base within a short period of time and were generously promoted by most states as a link between the state and the army on the one hand and the population on the other. In a number of states, this also took place under the aspect of a transition from a professional army to general conscription . In order to maintain the will of the population to go to war and to support this step, it was necessary to ensure that the soldiers were given the best possible care.

Not among the first to sign were the United Kingdom , which took part in the 1864 conference but did not join the convention until 1865, and Russia , which signed the convention in 1867. It has been reported that a British delegate said during the conference that he could not sign the convention without a seal. Guillaume-Henri Dufour , General of the Swiss Army, member of the International Committee and chairman of the conference, then cut a button from his tunic with his pocket knife and presented it to the delegate with the words “Here, Your Excellency, you have Her Majesty's coat of arms ". Austria , under the influence of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, acceded to the convention on July 21, 1866, the German Empire , founded in 1871, on June 12, 1906. However, important forerunner states had already become party to it. For example, Hesse ratified the convention on June 22, 1866 after it had already been signed in 1864, and Bavaria joined on June 30. In both cases this happened as a direct consequence of the war between Prussia and Austria. Saxony followed on October 25, 1866. The USA , which had also been represented at the conference, had great reservations for a long time , particularly because of the Monroe Doctrine, and did not join the convention until 1882. The work of Clara Barton , the founder of the American Red Cross , had a great influence . In total, the convention was signed by 57 states in the course of its history, 36 of them within the first 25 years from 1864 to 1889. Ecuador was the last state to enter into force on August 3, 1907, just six days before the revised version of 1906 came into force Convention of 1864 at.

Further development up to the Second World War

As early as 1868, additional articles to the Geneva Convention were proposed for the first time in order to extend its scope to include naval warfare. Despite being signed by 15 countries, this proposal was never ratified by any country and therefore never implemented due to a lack of support. Only the USA became a party when it joined the Geneva Convention in 1882. Nevertheless, the conflicting parties in the Franco-Prussian War (1870 to 1871) and in the Spanish-American War of 1898 agreed to observe the rules formulated in the additional articles. At the end of the 19th century, on the initiative of the Swiss Federal Council, a corresponding draft was drawn up again by the International Committee. At the first Hague Peace Conference in 1899, the Hague Convention III was concluded without the direct participation of the ICRC , with 14 articles adopting the rules of the Geneva Convention of 1864 for naval warfare. Under the influence of the sea battle at Tsushima on May 27 and 28, 1905, this convention was revised during the second Hague Peace Conference in 1907. The Convention, known as Hague Convention X, adopted the 14 articles of the 1899 version almost unchanged and, with regard to the enlargement, was essentially based on the revised Geneva Convention of 1906. These two Hague Conventions were the cornerstone for Geneva Convention II of 1949. The most important An innovation in the revision of the Geneva Convention in 1906 was the explicit mention of voluntary aid organizations to support the care of sick and wounded soldiers.

The further historical development of international humanitarian law was primarily shaped by the reactions of the international community and the ICRC to concrete experiences from the wars since the conclusion of the first convention in 1864. This applies, for example, to the agreements concluded after the First World War , including the 1925 Geneva Protocol in response to the use of poison gas . Contrary to popular belief, this agreement is not an additional protocol to the Geneva Convention, but belongs in the context of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Instead of the ICRC, the League of Nations, which was established in 1920, was largely responsible for its creation ; France is the depositary state of this Protocol. The most important impact of the First World War on the Geneva-based part of international humanitarian law was the Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War in 1929 as a reaction to the massive humanitarian problems involved in dealing with prisoners of war during the First World War. With this convention, the International Committee was explicitly mentioned in international humanitarian law for the first time. Article 79 gave the ICRC the opportunity to propose that the conflicting parties set up and organize a central office for the exchange of information on prisoners of war .

The first convention was also revised again that year, but not as extensive as the 1906 version of 1864 compared to the previous version. An important change, however, was the removal of the so-called all -participation clause ( clausula si omnes ), which was introduced in 1906 in the form of the article 24 had been newly included. According to her, the convention should only apply if all parties to a conflict had signed it. Although the clause would have been relevant when Montenegro entered the First World War, for example, no country ever invoked it during its validity from 1906 to 1929. Since it actually did not correspond to the humanitarian concerns of the Geneva Convention and had always been rejected by the ICRC, it can only be assessed as a wrong decision in retrospect and was consequently deleted from the convention during the revision in 1929.

A second major change was the official recognition of the Red Crescent and the Red Lion with the Red Sun as protective symbols with equal rights in Article 19 of the new version of the first Geneva Convention. The red lion, used exclusively by Iran, has not been in use since 1980, but must be respected as a still valid trademark if it is used. In addition, in its declaration of September 4, 1980, Iran reserved the right to reuse the Red Lion in the event of repeated violations of the Geneva Conventions in relation to the other two symbols.

At the 15th International Red Cross Conference in Tokyo in 1934, a draft for a convention for the protection of civilians in times of war was adopted for the first time. This followed the decisions of previous conferences which, based on the experience of the First World War, had asked the ICRC to take appropriate steps. The diplomatic conference of 1929 also voted unanimously in favor of such a convention. A conference planned by the Swiss government for the adoption of the draft in 1940 did not take place due to the Second World War. Appeals by the ICRC to the conflicting parties to voluntarily respect the Tokyo draft were unsuccessful.

Geneva Convention of 1949

In 1948, under the influence of the Second World War , the Swiss Federal Council invited 70 governments to a diplomatic conference with the aim of adapting the existing regulations to the experiences of the war. The governments of 59 countries accepted the invitation, twelve other governments and international organizations, including the United Nations , participated as observers. The International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies were called in as experts by decision of the conference. During the conference from April to August 1949, the two existing conventions were revised and the rules for naval warfare that had previously existed as Hague Convention IV were incorporated into the Geneva Conventions as a new convention. The Geneva lawyer and ICRC employee Jean Pictet played a major role in the preparation of the drafts submitted by the ICRC , making him the spiritual father of the 1949 agreements. The legally fixed mandate of the International Committee was significantly expanded by the four conventions. At the end of the Diplomatic Conference, the agreements were signed by 18 states on August 12, 1949.

The conclusion of the Geneva Convention IV “on the protection of civilians in times of war” was the most important extension of the scope of the Geneva Conventions; it is a direct result of experiences with the devastating effects of the Second World War on the civilian population and is essentially based on the 1934 draft. One year after the conference, the four currently valid agreements came into force on October 21, 1950. Austria and Switzerland , like the USA , were among the signatory states on August 12, 1949. Switzerland was the first country in the world to ratify the agreements on March 31, 1950, Austria followed on August 27, 1953. Until the conventions came into force on October 21, 1950, in 1950, Switzerland was followed by Monaco on July 5 and Liechtenstein on May 21. September and Chile on October 12th with further ratifications, India also joined the agreement on November 9th of the same year. The Federal Republic of Germany became a contracting party in a single legal act on September 3, 1954, with no distinction between signature and ratification, and the German Democratic Republic followed on August 30, 1956 . In the same year the number of 50 contracting parties was reached, eight years later 100 states had already acceded to the 1949 conventions.

Additional protocols from 1977

Due to the wars in the 1960s, such as the Vietnam War , the Biafra conflict in Nigeria , the wars between the Arab states and Israel and the wars of independence in Africa , the General Assembly of the United Nations passed resolution 2444 (XXIII ) "Respect for Human Rights in Armed Conflicts". This resolution reaffirmed the general validity of three fundamental principles of international humanitarian law: (1) the existence of restrictions on the choice of means of warfare; (2) the prohibition of attacks against the civilian population; (3) the obligation to distinguish between combatants and the civilian population and to spare the civilian population as much as possible. In addition, this resolution called on the UN Secretary General to investigate, in cooperation with the ICRC, to what extent the applicability of the existing provisions of international humanitarian law could be improved and in which areas an expansion of international humanitarian law through new agreements would be necessary. This was the impetus for the Diplomatic Conference from 1974 to 1977.

At the end of this conference, two additional protocols were adopted, which came into force in December 1978 and brought essential additions in several areas. On the one hand, both protocols integrated into the legal framework of the Geneva Conventions rules for permissible means and methods of warfare and thus above all for dealing with people involved in combat operations. This was an important step towards standardizing international humanitarian law. The rules of Additional Protocol I also specified a number of provisions of the four conventions of 1949, the applicability of which had proven inadequate. Paragraph 2 of Article 1 of the Protocol also adopted the so-called Martens' clause from the Hague Land Warfare Regulations, which specifies the three principles of custom , humanity and conscience as standards of action for situations that are not expressly regulated by written international law . Additional Protocol II was a response to the increase in the number and severity of non-international armed conflicts in the post-World War II period, particularly in the context of the liberation and independence movements in Africa between 1950 and 1960. It achieved one of the longest-running goals of the ICRC. In contrast to Additional Protocol I, Additional Protocol II thus represents less a supplement and specification of existing regulations than an expansion of international humanitarian law to a completely new area of application. In this sense, it can be used more as an independent and additional convention and less as an additional protocol be considered. Austria and Switzerland signed the protocols on December 12, 1977. Ghana were the first countries in the world to ratify the two additional protocols on February 28, and Libya on June 7, 1978. El Salvador followed suit on December 7 of the same year September 23rd. Ratification by Switzerland took place on February 17, 1982, Austria followed on August 13, 1982. Germany signed the protocols on December 23, 1977, but only ratified them about 13 years later on February 14, 1991. In 1982 there were 150 states Contracting parties to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. Additional Protocols I and II recorded 50 contracting parties in 1985 and 1986 respectively, and just six years later the number of 100 was reached.

Developments and problems after 1990

The renewed increase in independence efforts after the end of the Cold War and the rise of international terrorism , both combined with a significant increase in the number of non-international conflicts involving non-state conflict parties, presented the ICRC with massive challenges. Inadequacies in the applicability and enforceability of the two additional protocols of 1977, in particular, as well as a lack of respect for the Geneva Conventions and their symbols on the part of the parties involved in the conflict led to the fact that the number of delegates killed in their operations has increased significantly since around 1990 and that the authority of the ICRC has been increasingly in danger since then. Mainly due to the dissolution of the former socialist states of the Soviet Union, ČSSR and Yugoslavia after 1990, the number of contracting parties to the Geneva Conventions and their additional protocols rose sharply with the accession of their successor states. In the ten years from 1990 to 2000 alone, 27 countries acceded to the agreement, including 18 former republics of Eastern European countries.

In March 1992, the International Humanitarian Inquiry Commission based on Article 90 of the First Additional Protocol was constituted as a permanent body. At the beginning of the 1990s, the international community began to believe that serious violations of international humanitarian law pose a direct threat to world peace and can therefore justify intervention under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter . This was expressed in several resolutions of the UN Security Council , for example in 1992 in resolution 770 with regard to Bosnia-Herzegovina and resolution 794 with regard to Somalia and in 1994 with resolution 929 with regard to Rwanda . An important addition to international humanitarian law was the adoption of the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court in The Hague in 1998 and the entry into force of this agreement four years later. For the first time, a permanent international institution was created which, under certain circumstances, can prosecute serious violations of international humanitarian law.

During the US military operations in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (since 2003), the US government was repeatedly criticized for non-compliance with the Geneva Conventions, in particular when it came to dealing with prisoners in the Camp X-Ray prison camp at the US military base Guantánamo Bay in Cuba . After legal opinion of the US government is in the interned there prisoners from the ranks of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda to "unlawful combatants" (English. Unlawful combatants ) and not prisoners of war within the meaning of the Geneva Convention III. However, only a few countries around the world recognize the term “ illegal combatants ” as part of military and martial law. In addition, the United States has not yet fulfilled the obligation arising from Article 5 of Geneva Convention III to hold a competent tribunal that has to decide on the status of prisoners of war on a case-by-case basis. Likewise, it has not yet been clarified which prisoners would be protected by Geneva Convention IV if Geneva Convention III were inapplicable and to what extent its provisions will be fully complied with. Repeated allegations by released prisoners regarding serious violations of the rules of both conventions have not yet been publicly confirmed by an independent institution.

Following the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in the case v Hamdan. Rumsfeld on June 29, 2006, the US Secretary of Defense Gordon R. England announced in a memorandum dated July 7, 2006 that all prisoners of the US Army from the war on terror strictly according to the rules of common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions to be treated. In addition to the 450 prisoners in Guantánamo Bay at the time, this also applies to around 550 prisoners in other prisons, the existence of which has thus been explicitly confirmed by the United States authorities for the first time.

Third Additional Protocol from 2005 and Red Crystal

The controversy surrounding the Red Star of David, which is used by the Israeli society Magen David Adom instead of the Red Cross or the Red Crescent, led to considerations regarding the introduction of an additional protective symbol , according to an article published in 1992 by the then ICRC President Cornelio Sommaruga . It should be devoid of any actual or perceived national or religious meaning. In addition to the controversy about the sign of Magen David Adom, such a symbol is also of importance, for example, for the national societies of Kazakhstan and Eritrea, which, due to the demographic composition of the population in their home countries, strive to use a combination of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent.

The introduction of a new trademark through the adoption of a third additional protocol was originally intended to be implemented as early as 2000 as part of a diplomatic conference of all the signatory states to the Geneva Conventions. However, the conference was canceled at short notice due to the start of the Second Intifada in the Palestinian Territories. In 2005 the Swiss government again invited the signatory states to the Geneva Conventions to such a conference. It was originally supposed to take place on December 5th and 6th, but was then extended to December 7th. After Magen David Adom signed an agreement with the Palestinian Red Crescent a few days before the conference, which recognized its jurisdiction in the Palestinian territories and regulated the cooperation between the two organizations, Syria requested a similar agreement during the conference for the access of its national Red Crescent Society to the Golan Heights . Despite intensive negotiations and a compromise offer by the ICRC to Syria, which provided for the construction of a hospital on the Golan under the supervision of the ICRC, such an agreement was not concluded.

Contrary to previous practice, the third additional protocol was therefore not adopted by consensus, but after a vote with the necessary two-thirds majority. Of the states present, 98 voted for the protocol, 27 against and ten abstained. The official name for the new symbol is "Sign of the Third Additional Protocol", while the ICRC favors the name "Red Crystal" as a slang term. Switzerland and Austria, along with 25 other countries, signed the protocol on the day it was adopted, Germany on March 13, 2006. The first ratification took place on June 13, 2006 by Norway, the second on July 14, 2006 by Switzerland. The protocol entered into force six months after its second ratification on January 14, 2007. Austria became a contracting party on June 3, 2009, Germany on June 17, 2009.

Validity of older versions

Compared to the first convention of 1864 with ten articles, the existing agreement from the four conventions and their three additional protocols comprises over 600 articles. Even after new versions of the existing conventions were signed, the old versions remained in force until all contracting parties to the old version had signed a newer version. This is why, for example, the Geneva Convention was in effect from 1864 until 1966, when South Korea became a party to the 1949 Geneva Convention, succeeding the Republic of Korea. The 1906 version remained in force until the 1949 version was signed by Costa Rica in 1970. For the same reason, the two Geneva Conventions from 1929 were still legally valid until 2006, when the 1949 agreements achieved universal acceptance with the accession of Montenegro .

The Hague Conventions II and IV are still legally in force today. In addition, the Hague Land Warfare Regulations are also regarded as customary international law , i.e. generally applicable international law. This means that it also applies to states that have not explicitly signed this convention, a legal opinion that was reinforced, among other things, by a ruling by the International Military Court of Nuremberg in 1946.

Important provisions

Common Article 3

The text of Article 3 ( common article 3 ), which is identical in wording in all four conventions, reads:

- In the event of an armed conflict which is not international in character and which arises in the territory of one of the High Contracting Parties, each of the parties to the conflict is required to apply at least the following provisions:

- 1. Persons not directly participating in the hostilities, including members of the armed forces who have surrendered and persons incapacitated as a result of illness, injury, capture or any other cause, should at all costs Humanity shall be treated without any discrimination on grounds of race, color, religion or belief, sex, birth or property, or for any similar reason. For this purpose, it is and will be prohibited at any time and anywhere in relation to the above-mentioned persons:

- a. Assaults on life and limb, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;

- b. Capture of hostages;

- c. Impairment of personal dignity, in particular degrading and degrading treatment;

- d. Convictions and executions without prior judgment by a duly appointed court that offers the legal guarantees recognized by civilized peoples as essential.

- 2. The wounded and sick should be rescued and cared for.

- An impartial humanitarian organization such as the International Committee of the Red Cross can offer its services to the parties involved in the conflict.

- On the other hand, the parties involved in the conflict will endeavor to implement the other provisions of the present agreement in whole or in part by means of special agreements.

- The application of the above provisions has no influence on the legal status of the parties involved in the conflict.

On the one hand, the principle mentioned in point 1 of this article clarifies the common spirit of the four conventions. In this sense it can be briefly summarized as “Be human even in war!” . From a legal point of view, however, Article 3 above all represents the minimum consensus of humanitarian obligations for non-international armed conflicts, as the first sentence of the article makes clear. Until the adoption of Additional Protocol II, this article was the only provision in the Geneva Conventions that explicitly referred to domestic armed conflicts. Article 3 was therefore partly viewed as a “mini-convention” or “convention within the convention”. In a non-international conflict, it also applies to non-state parties to the conflict, such as liberation movements, which, due to the conception of the Geneva Conventions as international treaties, cannot be a party. In addition, Article 3 also obliges states to meet certain minimum standards in dealing with their citizens in the event of an internal armed conflict. It thus touches a legal area that was traditionally regulated solely by national law. The concept of human rights , which only began to have a universal dimension with the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the UN General Assembly on December 10, 1948, thus also became part of international humanitarian law. The aspect of human rights within international humanitarian law was expanded further by Additional Protocol I of 1977, which in Articles 9 and 75 provides for equal treatment of war victims regardless of race, skin color, gender, language, religion or belief, political or other views, national or social origin, assets, birth or other position or any other similar distinguishing feature based on disadvantageous distinction .

More common rules

Article 2, which is contained in all four conventions with identical wording, defines the situations in which the conventions are to be applied, on the one hand “... in all cases of declared war or any other armed conflict ... that arises between two or more of the High Contracting Parties ... " and on the other hand " ... even if the territory of a High Contracting Party is fully or partially occupied ... " . In addition, in the event that a power involved in the conflict is not a party to the contract, it explicitly rules out a restriction on validity that is comparable to the all-participation clause valid from 1906 to 1929. Article 4 of the individual agreements defines the persons protected in each case.

One of the provisions that already apply in peacetime is the obligation on the signatory states to ensure the widest possible dissemination of knowledge about the Geneva Conventions, both among the armed forces and among the civilian population (Articles 47, 48, 127 and 144 of Geneva, respectively Agreements I, II, III and IV, as well as Articles 83 and 19 and 7 of Additional Protocols I, II and III). In addition, the contracting parties undertake to criminalize serious violations of international humanitarian law through appropriate national laws (Articles 49, 50, 129 and 146 of Geneva Conventions I, II, III and IV and Article 86 of Additional Protocol I).

A contracting party may terminate the Geneva Conventions (Articles 63, 62, 142 or 158 of Geneva Conventions I, II, III or IV and Articles 99, 25 and 14 of Additional Protocols I, II and III). It must be reported to the Swiss Federal Council in writing and it will inform all other contracting parties. The termination takes effect one year after the notification, unless the terminating party is involved in a conflict. In this case, the termination is ineffective until the end of the conflict and the fulfillment of all obligations arising from the agreement for the terminating party. The four Geneva Conventions also contain a reference in the named articles to the validity of the principles formulated in Martens' clause even in the event of termination. In the history of the Geneva Conventions to date, however, no state has ever made use of the option of termination.

Geneva Convention I

Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 for the Improvement of the Lot of the Wounded and Sick of the Armed Forces in the Field

Injured and sick members of the armed forces are to be protected and cared for by each party involved in the conflict (Article 12) without distinction. In particular, their killing, use of force, torture and medical experiments are strictly prohibited. Personal information on injured or sick relatives of the opposing side must be registered and passed on to an international institution such as the ICRC Prisoner of War Agency (Article 16).

Attacks on medical facilities such as military hospitals and hospitals that are under the protection of one of the symbols of the Convention are strictly prohibited (Articles 19 to 23), as are attacks on hospital ships from land. The same applies to attacks on persons who are solely responsible for the search, rescue, transport and treatment of injured persons (Article 24) as well as for members of the recognized national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and other aid organizations recognized by their government who act analogously (Article 26). In Germany, in addition to the German Red Cross as the national Red Cross Society, the Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe and the Malteser Hilfsdienst are also recognized as voluntary aid organizations under Article 26. The persons named in Articles 24 and 26 are to be held in custody only as long as the care of prisoners of war makes it necessary, and otherwise released immediately (Article 28). In such a case, you are under the full protection of Geneva Convention III, but without being classified as prisoners of war yourself. In particular, they may not be used for activities other than their medical and religious tasks. Transports of wounded and sick soldiers are under the same protection as fixed medical service facilities (Article 35).

As a protective symbol in the sense of this convention, the color reversal of the Swiss national flag, the red cross on a white background (Article 38). Further protective symbols with equal rights are the red crescent moon on a white background and the red lion with the red sun on a white background. These protective symbols are to be used by authorized institutions, vehicles and people as flags, permanent markings or armbands.

Geneva Convention II

Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 for the Improvement of the Lot of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked in the Armed Forces at Sea

The Geneva Convention II is closely based on the Geneva Convention I in terms of its provisions, also because of its history. However, with regard to applicability, a clear distinction is made between members of the land and naval forces (Article 4). Members of the naval forces who landed on land for whatever reason are immediately protected by Geneva Convention I (also Article 4).

The protection provisions for sick, wounded and shipwrecked members of the armed naval forces are formulated analogously to the provisions of Geneva Convention I, including the obligation to provide indiscriminate aid and care (Article 12) and to register and transfer data to an international institution (Article 19) . The term “shipwrecked” also includes members of all branches of the armed forces, provided that they have landed on the water with or from an aircraft (Article 12).

The parties to the conflict can ask ships of neutral parties as well as all other accessible ships for help in taking over, transporting and caring for sick, wounded and shipwrecked soldiers (Article 21). All ships that comply with this request are under special protection. Specially equipped hospital ships , the sole purpose of which is to provide assistance to the named persons, may under no circumstances be attacked or manned (Article 22). The names and other information to identify such ships must be communicated to the opposing party at least ten days prior to commissioning. Attacks from the sea on facilities protected under the Geneva Convention I are prohibited (Article 23). The same applies to fixed facilities on the coast that are used exclusively by hospital ships to carry out their tasks (Article 27). Hospital ships in a port that falls into the hands of the opposing side are to be allowed free exit from that port (Article 29). Under no circumstances may hospital ships be used for military purposes (Article 30). This includes any hindrances to troop transport. All communication from hospital ships must be unencrypted (Article 34).

For the staff of hospital ships, protective provisions apply analogous to the staff of the sanitary facilities on land, as set out in Geneva Convention I. The same applies to ships that are used to transport wounded and sick soldiers (Article 38). The protection symbols as laid down in Geneva Convention I (Article 41) are used to identify protected facilities, ships and people. The outer hull of hospital ships is to be made completely white, with large dark red crosses on both sides and on the deck surface (Article 43). In addition, they should clearly display both a Red Cross flag and the national flag of their conflicting party.

Geneva Convention III

Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 on the Treatment of Prisoners of War

Important for the applicability of the Geneva Convention III is the definition of " prisoner of war " (English. Prisoner of War , POW) 4. Article prisoners of war are therefore all persons who have fallen into the hands of the other side and to one of the following groups belong:

- Members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict as well as members of militias and volunteer units, provided that they are part of the armed forces or of the naval position.

- Members of other militias and volunteer units, including armed resistance groups, belonging to a party to the conflict, provided they are under the uniform command of a responsible person, can be identified by a recognizable identifier, bear their weapons openly and behave according to the rules of martial law.

- Members of other regular armed forces who are subordinate to a government or institution that is not recognized by the capturing party.

- Individuals accompanying the armed forces without belonging to them, including civil members of the crew of military aircraft, war correspondents and employees of companies contracted to supply the armed forces or similar services.

- Members of the crews of merchant ships and civil aircraft of the parties involved in the conflict, unless they enjoy further protection under other international regulations.

- Residents of unoccupied territories who, without organizing themselves in regular units, spontaneously offered armed resistance when the opposing side arrived, provided they openly bear their weapons and behave according to the rules of martial law.

If there is any uncertainty about the status of a prisoner, he or she must be treated according to the provisions of Geneva Convention III until the status has been clarified by a competent tribunal (Article 5).

Prisoners of war are to be treated humanely under all circumstances (Article 13). In particular, their killing, any endangerment to their health, use of force, torture, mutilation, medical experiments, threats, insults, humiliation and public display are strictly forbidden, as are reprisals and reprisals. The life, physical integrity and honor of prisoners of war must be protected under all circumstances (Article 14). Prisoners of war are only obliged to give their surname and first name, their rank, their date of birth and their identification number or equivalent information (Article 17). The parties to the conflict are obliged to provide prisoners of war with an identity document. Items in the personal possession of prisoners of war, including rank badges and protective equipment such as helmets and gas masks, but not weapons, as well as other military equipment and documents, may not be confiscated (Article 18). Prisoners of war are to be accommodated as quickly as possible with sufficient distance from the combat zone (Article 19).

The accommodation of prisoners of war in closed camps is permitted, provided this is done under hygienic and non-health-endangering conditions (Articles 21 and 22). The conditions of accommodation must be comparable to the accommodation of the troops of the capturing party in the same area (Article 25). Separate rooms are to be provided for women. The supply of food and clothing must be sufficient in quantity and quality and should take into account the individual needs of the prisoners as far as possible (Articles 26 and 27). POW camps are to be provided with adequate medical facilities and personnel (Article 30). Prisoners of war with medical training can be used for corresponding activities (Article 32). Persons with special religious powers are to be granted the freedom to exercise their activities at any time; they are also to be exempted from all other activities (Articles 35 and 36). Canteens (Article 28), religious facilities (Article 34) and opportunities for sporting activities (Article 38) must be provided.

Lower ranks prisoners of war are obliged to show the officers of the capturing party the due respect (Article 39). Officers among the prisoners are only obliged to face higher-ranking officers and, regardless of their rank, the camp commandant. The text of the Geneva Convention III must be made available in a place accessible to every prisoner at all times in his mother tongue (Article 41). All prisoners are to be treated according to military practice according to their rank and age (Article 44). Lower ranks prisoners of war may, depending on their age and physical condition, be used for work (Article 49), NCOs, however, only for non-physical activities. Officers are not obliged to work, but they must be given the opportunity to do so if they so wish. Permitted activities are, for example, construction and repair work in the warehouse, agricultural work, manual labor, trade, artistic activity and other services and administrative activities (Article 50). None of these activities may have a military benefit for the capturing party or, as long as a prisoner does not give his consent, be dangerous or harmful to health. Working conditions should be comparable to those of the civilian population in the same area (Article 53), and prisoners should be adequately remunerated for their work (Articles 54 and 62).

The capturing party shall grant prisoners of war a monthly payment which, depending on their rank, should correspond to an amount in the national currency worth eight Swiss francs for soldiers of lower ranks, twelve francs for non-commissioned officers and between 50 and 75 francs for officers of various ranks ( Article 60). Prisoners of war are to be given the opportunity to receive and send letters and to receive money and goods. Prisoners of war may elect representatives to represent them vis-à-vis the authorities of the capturing party (Article 79). Prisoners of war are fully subject to the military law of the capturing party (Article 82) and are treated on an equal footing with the relatives of the opposing party with regard to their legal rights. Collective punishment and corporal punishment are prohibited as sanctions (Article 87). Penalties for successful escape attempts are inadmissible in the event of re-arrest (Article 91). An attempt to escape is considered successful if a soldier has reached his own armed forces or that of an allied party or has left the territory controlled by the other side.

Seriously wounded or seriously or terminally ill prisoners of war should, if possible, be brought to their home countries before the end of the conflict, if their condition and the circumstances of the conflict permit (Article 109). All other prisoners are to be released immediately after the end of the fighting (Article 118). For the exchange of information between the conflicting parties, they are obliged to set up an information office (Article 122). In addition, a central agency for prisoners of war must be set up in a neutral country (Article 123). The ICRC can propose that the conflicting parties take over the organization of such an agency. The national information offices and the central agency are exempt from postal charges (Article 124).

Geneva Convention IV

Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 for the Protection of Civilians in Time of War

The provisions of Geneva Convention IV apply to all persons who, in the event of an armed conflict, fall into the hands of a party to the conflict or an occupying power to whose nationality they do not belong, regardless of the circumstances (Article 4). This does not apply to nationals of states that are not parties to the Geneva Conventions, as well as nationals of neutral and allied states, if their home country has diplomatic relations with the country in whose hands they are. The Geneva Convention IV also does not apply to persons who are under the protection of one of the three other Geneva Conventions. Persons who are guilty of hostile acts or who have engaged in espionage or sabotage, or who are suspected of doing so, are not under the full protection of Geneva Convention IV if this would impair the security of the opposing side. However, they must be treated humanely under all circumstances. As soon as the security situation permits, they are to be granted all rights and privileges resulting from the agreement.

Civil hospitals must not be attacked under any circumstances (Article 18). They must also be marked with one of the protective symbols of the Geneva Convention I. Likewise, people who work exclusively or regularly as medical and administrative staff in hospitals are particularly protected (Article 20). The same applies to the transport of injured and sick civilians with the help of road and rail vehicles, ships and aircraft, if these are marked with one of the protective symbols (Articles 21 and 22). The contracting parties are obliged to ensure that children younger than 15 years of age who are permanently or temporarily without the protection of their families are not left to fend for themselves (Article 24). If possible, these children should be cared for in a neutral country for the duration of the conflict.

The persons protected under the Geneva Convention IV are entitled under all circumstances to respect for their person, honor, family ties, their religious beliefs and customs and other customs (Article 27). They are to be treated humanely without any distinction under all circumstances and protected from violence, threats, insults, humiliation and public curiosity. Women are to be given special protection against rape, forced prostitution and other lewd attacks against their person. However, the presence of a protected person does not mean that a particular place is protected from military operations (Article 28). Torture and blackmail of protected persons for the purpose of obtaining information is prohibited (Article 31). Looting, retaliation and hostage-taking are prohibited (Articles 33 and 34).

Protected persons have the right to leave the country in which they are, as long as it does not prejudice the security interests of the country (Article 35). The security and care of protected persons during the departure must be guaranteed by the country of destination or by the country of the nationality of the departing persons (Article 36). Protected persons should, as far as possible, receive medical care from the country in which they are located at a level comparable to the inhabitants of that country (Article 38). The internment of protected persons or their placement in assigned areas is only permitted if it is absolutely necessary for the security of the country concerned (Article 42). Internment for protection, at the request of the persons concerned, should be carried out if this is necessary due to the security situation. The extradition of protected persons to states that are not party to the Geneva Convention IV is not permitted (Article 45).

The right to leave the country under Article 35 also applies to residents of occupied territories (Article 48). Expulsion or deportation from an occupied territory against the will of the protected persons concerned is prohibited regardless of the reason (Article 49), as is the resettlement of civilians who are nationals of an occupying power to the territory of an occupied territory. Residents of an occupied territory may not be forced to serve in the armed forces of the occupying power. The destruction of civil facilities and private property in the occupied territory is prohibited unless it is part of necessary military operations (Article 53). The occupying power is obliged to ensure the supply of food and medical articles for the population of the occupied area and, if it is unable to do so, has to allow relief deliveries (Articles 55 and 59). The activities of the respective national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and similar aid organizations must not be restricted by the occupying power (Article 63). Recognition under Article 63 applies in Germany to the organizations already mentioned in the Geneva Convention I, as well as to the Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund , the Deutsche Lebens-Rettungs-Gesellschaft e. V. , the technical relief organization and the fire services . The criminal law of the occupied territory should remain in force, unless this represents a threat to the security of the occupying power or an obstacle to the implementation of Geneva Convention IV (Article 64).

Similar rules apply to the internment of protected persons as to the accommodation of prisoners of war (Articles 83, 85–94). Protected persons within the meaning of this convention are, however, to be accommodated separately from prisoners of war (Article 84). Educational opportunities must be ensured for children and adolescents. Protected persons may only be called upon to work at their own request (Article 95). An exception to this are people with medical training. Personal property of interned protected persons may only be confiscated by the occupying power in exceptional cases (Article 97). Interned persons may elect a committee to represent them vis-à-vis the authorities of the occupying power (Article 102). You must also be granted the right to receive and send letter post and to receive parcels (Articles 107 and 108).

For crimes committed by internees, the law of the area in which they are located applies (Article 117). Internment is to be terminated when the reasons for internment no longer exist, but at the latest as soon as possible after the end of the armed conflict (Articles 132 and 133). The interning party must bear the costs of repatriation (Article 135). As in Geneva Agreement III, all parties involved in the conflict must set up information offices and a central agency for the exchange of information (Articles 136–141).

Additional protocol I.

Additional Protocol of June 8, 1977 to the Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 on the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict

Additional Protocol I supplements the provisions of the 1949 versions of the four Geneva Conventions. In terms of its validity, it therefore refers in Article 1 to Article 2 of the four Geneva Conventions. Paragraph 4 of Article 1 also supplements the scope of Additional Protocol I to include armed conflicts in which peoples fight against colonial rule and foreign occupation as well as against racist regimes in exercising their right to self-determination , based on the corresponding contents of the Charter of the United Nations . Article 5 introduces the so-called protecting power system to monitor the application of and compliance with the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I, i.e. the designation of a protecting power by each of the parties involved in the conflict, and authorizes the ICRC to mediate in the search for all parties to the conflict accepted protecting powers. In addition, the ICRC and other neutral and impartial humanitarian organizations are given the opportunity to act as a substitute protective power.

Part II of Additional Protocol I contains provisions for the protection of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked. The definitions contained in Article 8 do not differentiate between military and civilians. The named persons are to be spared and protected, treated humanely and medically treated, looked after and cared for according to their needs (Article 10). Articles 12 to 15 extend the protection of medical units to civil units and define corresponding rules and restrictions. Article 17 contains provisions on the participation of civilians in aid measures. Hospital ships and other watercraft that are used in accordance with Geneva Convention II are, according to Additional Protocol I, under the protection of this Convention for the transport of wounded, sick and shipwrecked civilians (Article 22). Articles 24 to 31 contain regulations on the use and protection of medical aircraft. Measures for the exchange of information on missing persons and the handling of mortal remains are defined in more detail in Articles 32 to 34.

Part III contains regulations on methods and means of warfare. Article 35 restricts the parties to the conflict in choosing these methods and means, and in particular contains a ban on materials and methods that are likely to cause unnecessary injury or suffering or that are intended or that can be expected to do so cause widespread, long-lasting and severe damage to the natural environment . The prohibition of treachery contained in Article 37 goes back to comparable regulations contained earlier in the Hague Conventions, as does the prohibition of the order not to let anyone live (Article 40). Attacks against an incapacitated enemy are strictly prohibited (Article 41). This includes soldiers who have either surrendered, are wounded, or have been captured. Articles 43 to 45 contain provisions defining combatants and prisoners of war. This does not apply to mercenaries (Article 47).

Part IV contains supplementary rules for the protection of the civilian population. Article 48 lays down the principle that a distinction must be made between the civilian population and combatants at all times and that acts of war may only be directed against military targets. Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited (Article 51). Article 53 contains basic rules for the protection of cultural property and places of worship; Article 55 contains corresponding regulations for the protection of the natural environment. Attacks against installations or facilities containing dangerous forces (dams, levees and nuclear power plants) are prohibited, provided that such an attack can cause serious casualties among the civilian population (Article 56). This prohibition also applies if these facilities are military targets. In addition, a symbol consisting of three orange circles arranged in a row is defined to identify corresponding systems. Article 57 lays down precautionary measures to protect civilians when planning an attack. Undefended places and recognized demilitarized zones must not be attacked (Articles 59 & 60). Articles 61 to 67 contain rules on civil protection. For example, Article 66 defines an international symbol for the identification of personnel, buildings and materials of civil protection organizations, which consists of a blue triangle on an orange background. Articles 68 to 71 define aid measures for the benefit of the civilian population.

Articles 72 to 79 supplement the provisions of Geneva Convention IV on the protection of civilians who are under the control of one of the parties to the conflict. Refugees and stateless persons are now protected accordingly (Article 73), as are journalists (Article 79). Articles 80 to 84 define implementing provisions for the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I. Article 81 is explicitly dedicated to the activities of the Red Cross and other humanitarian organizations. Rules on penalizing violations of the Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocol are contained in Articles 85 to 91. The establishment of an international investigative commission (Article 90) is particularly important .

The final provisions of Additional Protocol I, such as regulations on entry into force, accession, amendments and termination, are contained in Articles 92 to 102. Appendix I defines ID cards, protective symbols and labels as well as light and radio signals used as identification signals for various applications.

Additional protocol II

Additional Protocol of June 8, 1977 to the Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 on the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflict

Additional Protocol II defines rules for all armed conflicts that are not covered by Article 1 of Additional Protocol I. These are conflicts that take place on the territory of a Party to the Additional Protocol between its regular armed forces and breakaway armed forces or other organized armed groups (Article 1).

Part II defines basic rules for human treatment. All persons who do not participate directly or no longer in hostilities have the right to respect for their person, their honor and their convictions and are to be treated with humanity under all circumstances. The order not to let anyone live is forbidden (Article 4). Attacks on the life, health and well-being of these persons, especially deliberate homicide and torture, are explicitly prohibited. Article 6 regulates the prosecution of offenses related to the armed conflict. Part III contains provisions for the treatment of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked. These are similar to the corresponding rules of Additional Protocol I (Articles 7 and 8), also with regard to the protection of medical personnel and the corresponding means of transport (Articles 9 to 12). Part IV defines regulations for the protection of the civilian population. Here, too, these regulations are similar to those of Additional Protocol I, including the protection of systems and facilities that contain dangerous forces (Article 15) and the protection of cultural property and places of worship (Article 16).

The final provisions of Additional Protocol II, including distribution, accession and entry into force as well as amendments and termination, are contained in Part V.

Additional protocol III

Additional protocol of December 8, 2005 to the Geneva Agreement of August 12, 1949 on the acceptance of an additional trademark

The sole aim of adopting Additional Protocol III was the introduction of a new protective symbol in addition to the protective symbols of the Red Cross, the Red Crescent and the Red Lion with the Red Sun already defined by the Geneva Conventions.

According to Article 2, the new trademark enjoys the same status as the three existing symbols. It is in the form of a square, pointed red frame on a white background. An illustration of the symbol is included in the appendix to Additional Protocol III. The conditions for the use of this symbol are the same as for the three existing symbols, in accordance with the provisions of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the two additional protocols of 1977. The contracting parties may at any time, even temporarily, use a symbol that deviates from their commonly used trademark use if this increases the protective effect. Article 3 regulates the use of the new trademark as a mark (for indicative purposes). For this purpose, either one of the three existing protective symbols or a combination of these symbols may be affixed inside the symbol. In addition, symbols that have been effectively used by a contracting party and the use of which was transmitted to the depositary state before Additional Protocol III came into force may also be used within the new symbol.

Article 4 contains provisions on the use of the new symbol by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. According to Article 5, the medical and pastoral staff of missions under the supervision of the United Nations may also use one of the three existing or the new protective symbols. Article 6 obliges the contracting parties to prevent misuse of the new trademark. Articles 7 to 14 contain the final provisions of Additional Protocol III.

Implementation in practice

Penalty for violations

The Geneva Conventions on their own are voluntary commitments of the signatory states and do not contain any stipulations on sanctions for violations. However, as already mentioned, the agreements contain an obligation to criminalize serious violations of international humanitarian law. Violations of the Geneva Conventions and other rules of international humanitarian law are, for example, punishable in Germany by the International Criminal Code that came into force in 2002 . Article 25 of the Basic Law also integrates “the general rules of international law” into federal law and gives it priority over national laws. Similar provisions can be found in Art. 5 Para. 4 and Art. 191 of the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation . Special provisions on the punishment of violations of the Geneva Conventions are contained in the sixth section of the Swiss Military Criminal Law passed in 1927, currently in the 2007 version. In Austria , the Geneva Conventions and their two additional protocols have become part of Austrian law through publication in the Austrian Federal Law Gazette. The legal basis for the criminal liability of violations are in particular Article 9 of the Federal Constitutional Act and Section 64 of the Criminal Code . In the GDR, § 93 StGB (GDR) of January 12, 1968 regulated the criminal liability of war crimes and § 84 StGB (GDR) a corresponding exclusion of the statute of limitations . The obligation, which is also contained in the agreements, to disseminate knowledge about the contents of the conventions is known as dissemination work and is usually taken on by the national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Both the reinforcement of punishments at the national level and the education of the broadest possible public through dissemination work are seen by the ICRC as necessary measures to increase the enforceability and acceptance of the agreements.

In order to investigate allegations of serious violations of the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I, the International Humanitarian Investigation Commission based on Article 90 of the Additional Protocol has existed as a permanent body since 1991 . However, it has purely investigative powers and no powers to prosecute states or individuals. The International Criminal Court based in The Hague with the entry into force of the Rome Statute- the possibility of war crimes to prosecute as its basis in international law since 1 July 2002 under certain conditions. Article 8 of the Rome Statute defines war crimes in paragraph 2, among other things, as "serious violations of the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949", as "serious violations of the laws and customs applicable within the established framework of international law in international armed conflict" , including violations of important provisions of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations, as well as armed conflicts without an international character as "serious violations of the common Article 3 of the four Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949". The International Criminal Court only becomes active with regard to criminal prosecution if there is no adequate national jurisdiction or if this is not able and willing to prosecute the offenses concerned. However, for various reasons the International Criminal Court is not recognized by a number of countries. These include the USA, Russia, the People's Republic of China, India, Pakistan and Israel.

International acceptance and participating organizations

The only institution that is explicitly named as a controlling body in the Geneva Conventions is the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). As a rule, the ICRC treats its reports on the control missions and the results of its delegates' investigations as confidential and only forwards them to the relevant party. On the basis of likewise confidential communication, the ICRC then tries to persuade the responsible party to eliminate existing violations of the provisions of the Geneva Conventions and to enforce the prosecution of serious violations. From the ICRC's point of view, this confidentiality is a basic requirement for maintaining its strict impartiality and neutrality and thus its authority as an intergovernmental mediation and control institution. The committee therefore only publishes its reports if a partial publication by a party concerned produces a falsified picture that grossly misrepresents the situation of the protected persons concerned and thus seriously endangers their status. The aim of the publication is then political and diplomatic pressure on the responsible party from the national and international public.

Switzerland is the depositary state of the Geneva Conventions . With currently 196 signatory states, the Geneva Conventions of 1949 are the most widespread international treaties in the world and the first and so far only international agreements that have achieved universal acceptance. The number of contracting parties is currently higher than the number of member states of the United Nations and the states recognized by the UN. On April 2, 2014, Palestine was the last country to join the agreement. The contracting parties of the first two additional protocols from 1977 are 174 and 168 states respectively, the third additional protocol from 2005 has been ratified by 72 countries. Changes and extensions to the conventions and their additional protocols can only be decided by a diplomatic conference with the participation of all signatory states.

Only states can become official contracting parties. Non-governmental organizations such as liberation movements can, however, voluntarily and unilaterally undertake to comply with the conventions. An example of this was the declaration of compliance with the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Additional Protocol I of 1977, which the African National Congress (ANC) made on November 28, 1980 for its armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe ("The Spear of the Nation") at the ICRC deposited. There were similar voluntary commitments from the Pan-African Congress (PAC) and the South West African People's Organization (SWAPO), which is active in Namibia . The Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) issued a similar declaration on compliance with the four Geneva Conventions and their two additional protocols on June 21, 1989 . However, it did not make this declaration in the form of a voluntary commitment to the ICRC, but rather as an application to join the Swiss Department for Foreign Affairs , since the PLO saw itself in the role of the government of the State of Palestine. In this way she hoped to be recognized as an official contracting party. On September 13, 1989, the Swiss government informed the other contracting parties that, due to the legal uncertainty surrounding the existence of the State of Palestine, it was unable to decide whether to recognize this declaration as official accession. The acceptance of such declarations by the ICRC was not without controversy, as it was seen in part as a de facto recognition of these movements and thus as a violation of the impartiality and neutrality of the ICRC. Despite such voluntary commitments, the enforcement of the Geneva Conventions and in particular the Additional Protocol II in non-international armed conflicts is associated with particular problems, since the non-state conflicting parties involved in such situations are not bound by them as contracting parties to the Geneva Conventions.

Relations with the Hague Land Warfare Regulations

Within humanitarian law developed in addition to the codified in the Geneva Conventions Geneva law nor the so-called Hague law . Based on its historical origins, Geneva law primarily regulates how to deal with so-called non-combatants, i.e. persons who are not involved in the fighting in the event of an armed conflict. These are wounded, sick and captured soldiers and civilians. In contrast, the Hague Law mainly contains provisions on permissible means and methods of warfare and thus above all rules for dealing with the people involved in the fighting, the combatants. The basis of Hague Law is primarily a series of Hague Conventions concluded at the International Peace Conferences in The Hague in 1899 and 1907 , the most important of which is the Hague Land Warfare Regulations of 1907.

Essential parts of the original Hague law have been integrated into Geneva law in a significantly expanded form in the form of the convention " on the treatment of prisoners of war " of 1929 and 1949 and the two additional protocols from 1977. Even the Geneva Protocol of 1925 is now often viewed as part of Geneva law, although due to its history and content it is actually part of the Hague tradition of international humanitarian law. In addition, the separation of these two areas with regard to the treatment of combatants and non-combatants was not strict and consistent from the start. This can be seen, for example, in the rules on the treatment of civilians in the Hague Land Warfare Regulations, which also formed the basis for an extension of Geneva law in the form of the 1949 Geneva Convention “on the protection of civilians in times of war” . The Geneva Conventions III and IV stipulate in Art. 135 ff. And Art. 154 that the rules contained in them should supplement the corresponding sections of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations. How this should be done in individual cases on the basis of generally applicable principles of interpretation such as lex posterior derogat legi priori (“the later law takes precedence over the earlier”) and lex specialis derogat legi generali (“the special norm takes precedence over the general law”) remains open .

literature

German-language books

- German Red Cross (Ed.): The Geneva Red Cross Agreement of August 12, 1949 and the two additional protocols of June 10, 1977 as well as the Agreement on the Laws and Customs of Land War of October 18, 1907 and Annex (Hague Land Warfare Regulations). 8th edition. Writings of the German Red Cross, Bonn 1988.

- Horst Schöttler and Bernd Hoffmann (eds.): The Geneva additional protocols: comments and analyzes. Osang Verlag, Bonn 1993, ISBN 3-7894-0104-8 .

- Jana Hasse, Erwin Müller, Patricia Schneider: Humanitarian international law: political, legal and criminal court dimensions. Nomos-Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2001, ISBN 3-7890-7174-9 .

- Hans-Peter Gasser: Humanitarian international law. An introduction. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2007, ISBN 978-3-8329-2802-5 .

English language books

- Jean Simon Pictet (Ed.): The Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949: Commentary. Four volumes. ICRC, Geneva 1952–1960.

- Geoffrey Best: Humanity in Warfare: The Modern History of the International Law of Armed Conflicts. Columbia University Press, New York 1980, ISBN 0-231-05158-1 .

- Frédéric de Mulinen: Handbook on the Law of War for Armed Forces. ICRC, Geneva 1989, ISBN 2-88145-009-1 .

- Dieter Fleck (Ed.): The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-923250-5 .

- International Committee of the Red Cross: Handbook of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. 13th edition. ICRC, Geneva 1994, ISBN 2-88145-074-1 .

- François Bugnion: The International Committee of the Red Cross and the protection of war victims. ICRC & Macmillan, Geneva 2003, ISBN 0-333-74771-2 .

- François Bugnion: Towards a comprehensive solution to the question of the emblem. 4th edition. ICRC, Geneva 2006.

- Frits Kalshoven , Liesbeth Zegveld : Constraints on the waging of war: an introduction to international humanitarian law. 3. Edition. ICRC, Geneva 2001, ISBN 2-88145-115-2 , pdf .

- Angela Bennett: The Geneva Convention. The Hidden Origins of the Red Cross. Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire 2005, ISBN 0-7509-4147-2 .

- Derek Jinks: The Rules of War. The Geneva Conventions in the Age of Terror. Oxford University Press, New York 2006, ISBN 0-19-518362-2 .

- Marco Sassòli, Antoine A. Bouvier: How does law protect in war? Cases, documents and teaching materials on contemporary practice in international humanitarian law. 2nd Edition. ICRC, Geneva 2006.

French language books

- Eric David: Principes de droit des conflits armés. 3. Edition. Emile Bruylant, Brussels 2002, ISBN 2-8027-1685-9 .

items

- Cornelio Sommaruga: Unity and Plurality of the emblems. In: International Review of the Red Cross. 289/1992. ICRC, pp. 333-338, ISSN 1560-7755 .

- René Kosirnik: The 1977 Protocols: a landmark in the development of international humanitarian law. In: International Review of the Red Cross. 320/1997. Ikrk, pp. 483-505, ISSN 1560-7755 .

- Jean-Philippe Lavoyer, Louis Maresca: The Role of the ICRC in the Development of International Humanitarian Law. In: International Negotiation. 4 (3) / 1999. Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 503-527, ISSN 1382-340X .

- Dietrich Schindler : Significance of the Geneva Conventions for the contemporary world. In: International Review of the Red Cross. 836/1999. IKRk, pp. 715-729, ISSN 1560-7755 .

- François Bugnion: The Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949: from the 1949 Diplomatic Conference to the Dawn of the New Millennium. In: International Affairs. 76 (1) / 2000. Blackwell Publishing, pp. 41-50, ISSN 0020-5850 .

- Howard S. Levie: History of the law of war on land. In: International Review of the Red Cross. 838/2000. ICRC, pp. 339-350, ISSN 1560-7755 .

- Dietrich Schindler: International Humanitarian Law: Its Remarkable Development and its Persistent Violation. In: Journal of the History of International Law. 5 (2) / 2003. Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 165-188, ISSN 1388-199X .

- Gerrit Jan Pulles: Crystallising an Emblem: On the Adoption of the Third Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions. In: Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law. 8/2005. Cambridge University Press, pp. 296-319, ISSN 1389-1359 .

Web links

German language versions of the current agreements

- Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 for the Improvement of the Lot of the Wounded and Sick of the Armed Forces in the Field

- Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 for the Improvement of the Lot of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked in the Armed Forces at Sea

- Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 on the Treatment of Prisoners of War

- Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 for the Protection of Civilians in Time of War

- Additional Protocol of June 8, 1977 to the Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 on the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I)

- Additional Protocol of June 8, 1977 to the Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949 on the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II)

- Additional Protocol of December 8, 2005 to the Geneva Agreement of August 12, 1949 on the Acceptance of an Additional Protective Symbol (Protocol III)

Further information

- DRK - Geneva Agreement Information from the German Red Cross

- Austrian Red Cross - What is humanitarian international law? ( Memento of August 20, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) WCC factsheet (PDF; 440 kB)

- International Humanitarian Law - Treaties & Documents Text of all conventions in the previous versions (English)

- List of signatory states to the Geneva Conventions of August 12, 1949

- Additional emblem for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement Information on the additional symbol

- Conférence diplomatique sur la réaffirmation et le développement du droit international humanitaire applicable dans les conflits armés (1973–1979) in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives