Prisoners of war of the Second World War

There were prisoners of war in World War II on the side of the Allied forces and the Axis powers . The Second World War began with the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. On September 2, 1945, the Second World War ended with the surrender of Japan . Internment must be distinguished from captivity .

Legal status

“Prisoner of war” represents a status under international law that is intended to protect prisoners. The group of people includes combatants of the enemy armed forces, but also doctors, paramedics and clergy, insofar as they belong to them. This protection was regulated and contractually agreed in the Hague Land Warfare Regulations , the Hague Agreement , the Geneva Protocol and the Geneva Conventions .

In Europe, the situation in the eastern theater of war differed from that in the western theater of war in that the conduct of the war did not seek compliance with the Hague Land Warfare Regulations and the two Geneva Conventions on the Treatment of Prisoners of War and the Wounded by the German Reich and the Soviet Union. The “Soviet regulations on the treatment of prisoners of war”, however, corresponded in many respects to international war law, even though the Soviet Union, unlike the German Reich, had not acceded to the Geneva Convention on POWs or the Hague Land Warfare Regulations.

According to Art. 75 of the Geneva Convention of 1929 "the repatriation of prisoners of war had to take place as soon as possible after the conclusion of peace". With the formal legal objection that the state of war persisted even after the unconditional surrender of the German armed forces , a large number of German prisoners of war were held in Allied custody beyond May 8, 1945. In addition, the Control Council Proclamation No. 2 of September 20, 1945 imposed on the German authorities to carry out all measures prescribed by the Allied representatives for restitution, reinstatement, restoration, reparation, reconstruction, support and rehabilitation. This also included providing means of transport, systems, equipment and materials of all kinds, manpower , personnel and professional and other services for use within and outside Germany . At the Yalta conference in February 1945, the great powers had already decided that prisoners of war could be obliged to perform work after an armistice and that reparations would be demanded from Germany not only in the form of deliveries in kind, but also through the use of German labor.

At the Moscow conference in April 1947, the Allied Foreign Ministers decided to release all German prisoners of war by the end of 1948, which the Soviet Union subsequently underwent by sentencing numerous prisoners of war as alleged war criminals to long prison terms, so that the last prisoners did not return home until 1955 Ten thousand returned to Germany. Since 1950, the Central Legal Protection Agency represented the interests of Germans who were still in Allied custody.

Third party help

States and international organizations not involved in the war provided assistance in accordance with the rules of international martial law to ease the fate of prisoners of war . The assistance included:

- Representation of interests by a protecting power

- Supervision by the International Committee of the Red Cross

- Exchange of prisoners of war and wounded

- Mediation of prisoner-of-war mail

Axis soldiers

Axis prisoners of war in custody by the Western Powers

About 3,630,000 Wehrmacht soldiers were in British camps in Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Canada, Malta, Madagascar and other countries. Among them were 58,600 Austrians.

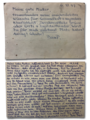

Approximately 3,100,000 German prisoners of war were in US camps, including around 371,000 in the USA . 135,000 were captured in Tunisia in 1943 , 10,000 in Italy and 182,000 in the 1944 invasion of Normandy . Every prisoner of war received a postcard immediately after his capture and with every change of address on which he could give his relatives information about his state of health as well as his current address and prisoner number (see images). The prisoners were distributed to numerous camps. “ Fraternization ” was not wanted; in the southern states the men were employed in agriculture, where they competed in part with African Americans, who often worked in poor working conditions, with low prestige and low wages. Many prisoners of war developed an "almost friendly" relationship with the US guards; the farmers often thanked them with small gifts or invitations to eat; many stayed in letter contact with the farmers after the repatriation and also received parcels. The food in the camps was initially better than before in the Wehrmacht and also better than for the US civilian population; After the end of the war from July to August 1945, the rations were drastically reduced, cigarettes and alcohol were not available, but were then increased again. The Germans received American army clothing marked “POW” (prisoner of war); But they also had the right to wear their uniform, badges and medals. They could organize sporting events, form theater and music groups.

Many had come with reservations "against the allegedly cultured and superficial America" and now also had other experiences. The US authorities began a reeducation and a small number of volunteers enjoyed special training in order to be able to participate in the construction of the country as the “vanguard of the new, democratic Germany” after their return. After the end of the war, many of the Germans became potential competitors of the demilitarized US veterans on the labor market and were therefore quickly repatriated. The United States began releasing prisoners of war from mid-May 1945, but also transferred 740,000 prisoners to France, 123,000 to Great Britain, 14,000 to the Netherlands, 30,000 to Belgium and 5,000 to Luxembourg due to labor requirements. Prisoners were also handed over to Poland and Czechoslovakia to make amends. France forced around 50,000 German prisoners of war to do high-risk forced labor as deminers. General George S. Patton wrote: "I am also opposed to sending PW's to work as slaves in foreign lands [in particular, to France] where many will be starved to death." In the spring of 1946 the ICRC was finally allowed to visit and To give limited amounts of food to prisoners of war in the American Zone.

During the Moscow Conference in March and April 1947 there were 435,295 prisoners in Great Britain, 641,483 in France and 14,000 in the US. The conference agreed to release all prisoners to Germany by December 31, 1948. German prisoners of war in France had the opportunity to continue working as a freelance civilian worker for a year, e.g. B. in agriculture.

Losses among German prisoners of war

The following table shows the number of Wehrmacht and Waffen SS prisoners of war in captivity in each country and the number of prisoners of war who perished in captivity. The figures show that the death rates for prisoners of war on the Eastern Front were immensely high compared to the death rates in the camps of the Western Allies. But there were also clear differences among the Western Allies. The death rates of German prisoners of war in the custody of the Free French , especially in North Africa, were significantly higher than in the camps in the USA or Great Britain.

| Land of captivity | Wehrmacht and SS prisoners of war |

Losses absolutely |

Losses in percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 937,000 | 24,178 | 2.6 |

| USSR | 3,150,000 | 1,094,250 | 34.7 |

| Eastern and Southeastern Europe | 289,000 | 93,028 | 32.2 |

| Great Britain | 3,635,000 | 1,254 | 0.03 |

| United States | 3,097,000 | 5,802 | 0.2 |

| other | 76,000 | 675 | 0.9 |

| total | 11,094,000 | 1,219,187 | 11.0 |

According to the information from the tracing service of the German Red Cross , the fate of a further 1,300,000 German military personnel is unclear, they are considered missing .

In American camps in France and Germany (for example in the Rhine meadow camps ) there was a death rate of 0.5 to 1 percent due to insufficient care and accommodation, but these camps were closed very quickly. Mortality rates were much lower in prison camps in the United States.

German soldiers in Soviet custody

Between 1941 and 1945 an estimated fell from 3.2 to 3.6 million soldiers of the Wehrmacht in Soviet captivity . 1.11 million were killed or never returned. During the First World War , the death rate of German prisoners of war in Russian hands was 40 percent.

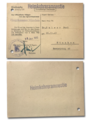

Prisoners of war of the Soviet Union were registered after being brought to a camp and a personal file was created according to the example shown here. The personal files that were closed when the prisoners returned are in the safekeeping of the Federal Archives Service of Russia - Reich Foundation - Russian Reich War Archives (RGWA) in Moscow . The published figures do not always make a clear distinction between prisoners of war and civilians and other internees who were held captive by the Red Army or Soviet authorities until 1956.

On the occasion of the Moscow Foreign Ministers' Conference in March 1947, the Allies agreed the release of all prisoners of war by the end of 1948. According to Soviet information, 890,532 German prisoners of war were in the Soviet Union at that time, and 1,003,974 had been released since May 1945 and sent back to Germany. Between March 1, 1947 and December 1, 1948, 447,367 prisoners returned from the USSR. Contrary to the agreements of March 1947, 443,165 were still in prison at the beginning of 1949. On January 24, 1949, the USSR responded to an inquiry from the Western Allies about the fate of these prisoners with the announcement that "the repatriation will come to an end in the course of 1949".

On September 28, 1949, the Politburo of the CPSU decided to release all prisoners of war, with the exception of those convicted of military tribunals, by January 1, 1950. Thereupon the Ministry of the Interior (MWD) issued an order on November 28, 1949 for the conviction of

- Members of the general and Waffen SS units

- Military personnel in POW and other camps as well as in police units and army judicial service had served

- Employees of enemy intelligence and defense organs of the Wehrmacht.

After 1112 prisoners of war had been convicted of war crimes committed in the Soviet Union by April 1948, and 3750 judgments had been passed between October 1947 and June 1949 (6036 investigative proceedings were still ongoing in June 1949), 13,603 prisoners of war were convicted in November and December 1949 alone, among others The investigation had not been completed by January 1, 1950, about 7,000 cases. Another 1,656 convictions took place in January 1950. Almost 86% of the judgments were for 25 years in a camp.

On May 4, 1950, the USSR declared that the repatriation (retrieval) of German prisoners of war from the Soviet Union was now completely completed. A total of 1,939,063 prisoners of war have returned to their homeland since Germany's surrender. According to this, 9,717 people convicted of war crimes remained in the Soviet Union, 3,815 people against whom proceedings are pending and 14 sick people who cannot be transported.

The last major release of prisoners of war from the Soviet Union (" Return of the Ten Thousand ") took place in 1955. This was preceded by a state visit by the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer from September 8 to 14, 1955 to establish diplomatic relations and the release of German prisoners of war. Likewise, the last homecoming train arrived in Austria only after the conclusion of the State Treaty of 1955 .

German soldiers in Yugoslav custody

According to an analysis by Böhme, around 80,000 German and Austrian soldiers died in Yugoslav captivity. Due to the confusing situation of the last days of the war, the number of soldiers captured during the surrender of the Wehrmacht units in Yugoslavia cannot be precisely determined. Schmider, who relies on the Böhme figures, estimates that it was between 175,000 and 200,000. If one takes into account that the Red Cross counted only about 85,000 returnees in 1948/1949 , less than half of the prisoners of war survived captivity.

Japanese soldiers in Allied custody

The first Japanese prisoner of war in the Pacific War was Sakamaki Kazuo .

Fred Fedorowich names between 19,500 and 50,000 Japanese prisoners of war that Australia and the United States took in the Southwest Pacific between 1942 and 1945.

Yamamoto Taketoshi counts around 208,000 Japanese prisoners of war in total, including prisoners of the communist and nationalist armies of China and the Soviet Union.

About 600,000 Japanese were captured by the Soviets at the end of World War II as part of Operation August Storm ; Many of them perished while working in Siberian mines.

Allied soldiers

Soviet soldiers in German custody

Between 1941 and 1945 well over 5 million Soviet soldiers fell into German captivity . 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war perished. Approximately 80,000 Jewish prisoners of war members of the Red Army were murdered. For other prisoners of war, the death rate was a maximum of two percent.

Work assignments of Soviet prisoners took place even before the Fuehrer's order of October 31, 1941. Although in March 1941 the Wehrmacht High Command had expected two to three million Soviet prisoners of war for the weeks after the attack, the summer and autumn of 1941, no at least reasonably adequate preparations had been made for their living accommodation and supplies. Most of the prisoners camped outdoors in the most disastrous conditions. In addition, there was an absolutely inadequate diet, poor hygiene and hardly any medical care, so that many died of diseases such as dysentery and typhus epidemics . Even before the war began, the starvation of so many Soviet soldiers had been factored into the so-called hunger plan . The Zeithain camp z. B. is also called death camp, since the wounded or sick in hospitals who were no longer able to work were still undersupplied. Soviet prisoners of war were also imprisoned in German concentration camps, for example in Sachsenhausen concentration camp . They were murdered in numerous ways, such as: B. by means of a shot in the neck , hanging, lethal injections of various substances and mass shootings ( Dachau concentration camp , Buchenwald concentration camp ). Human experiments with Soviet prisoners of war have been documented for the Neuengamme concentration camp ( tuberculosis ) and for the Auschwitz concentration camp (attempted poisoning of 600 prisoners with Zyklon B ).

Hundreds of thousands of them - as well as fallen soldiers of the Red Army and Soviet forced laborers during the Nazi era - are lying in Soviet war cemeteries in Germany , and countless were buried in mass graves. Some of their corpses gradually come to light.

The number of Soviet prisoners of war handed over to the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD as "politically intolerable" by the Wehrmacht after July 1941 is estimated to be well over 140,000 (see also Commissar Order ) .

1,836,000 Soviet prisoners of war returned to the Soviet Union. Since Stalin viewed the capture as treason, some of these returnees were subjected to repression. 16–17 percent of them were integrated into punitive battalions and a further 16–17 percent were imprisoned in the GULag camps. About two thirds of the former prisoners of war were therefore not punished. However, some of them had difficulty finding jobs or were expelled from the Communist Party .

In his speech at the end of the war, Federal President Joachim Gauck paid tribute to the Soviet prisoners of war on May 6, 2015. Her suffering was never properly recognized in Germany. On May 20, 2015, the German Bundestag decided to financially compensate the surviving former Soviet prisoners of war who were only fully rehabilitated in their home countries after the end of the USSR. It is assumed that there were around 4,000 former soldiers. The relevant resolution states: "Former Soviet prisoners of war should be granted a symbolic financial recognition amount without recognition of a legal obligation / legal reason."

Western Allied soldiers in German custody

These soldiers came in particular from Belgium, France, Holland, Norway, Poland, Great Britain, the USA, Serbia and, after the break of the alliance, also from Italy.

In contrast to the treatment of Soviet prisoners of war, the treatment of West Allied prisoners of war was generally good and the Geneva Convention was adhered to. Of the 232,000 US, British, Canadian and other soldiers, 8,348 did not survive the war, which is 3.5%.

The names " Stalag " ( prisoner-of-war team main camp , mainly subordinated to the Wehrmacht), " Stalag Luft " ( Luftwaffe prisoner-of-war team main camp , subordinate to the Air Force) and "Marlag" ( navy prisoner-of-war team main camp , subordinate to the General Marine Main Office ) , also “ Oflag ” ( prisoner of war officers camp ), “Dulag” ( prisoner of war transit camp ), “Heilag” ( prisoner of war returnees camp ) and “ Ilag ” ( internment camp ).

In some cases, after being released pro forma from captivity, some of the Allied soldiers were shot under conditions and regulations that were contrary to international law ( Aktion Kugel ) or taken to concentration camps .

Employment in industries, mining, or cleaning up was common. Their work in the armaments industry violated international law.

According to Hitler's command of October 18, 1942, members of commando units were to be killed down to the last man, contrary to international law, and if, in exceptional cases, prisoners were taken, they would have to be handed over to the Reichsführer SS security service for later execution .

Most of the soldiers' prisoner-of-war mail was handled by Switzerland. The PTT took on a proactive mediating role and there was intensive communication with the Deutsche Reichspost and the French Post. On October 24, 1939, the first shipment of prisoner-of-war mail from Germany to the south of France arrived in Basel 17 Transit . There were 200 postcards from French prisoners of war who wrote on preprinted postcards that they had been captured and that they were doing well.

From December 1, 1939, a car with German prisoner-of-war mail from France rolled via Basel 17 Transit to Frankfurt every day . In the opposite direction, the mail from French prisoners of war was handed over by the Deutsche Reichspost to the Basel Transit post office, where it was reloaded by the PTT and forwarded to France via Geneva. From 1940 the PTT also brokered postal traffic between Germany and Great Britain and their colonies. In order to avoid the chaos of war, detours were accepted. The prisoner of war mail between Germany and Great Britain was partly processed via Spain (Gibraltar) .

Allies in Japanese custody

During the Pacific War , British, Dutch, Australian, New Zealand and American soldiers became Japanese prisoners of war. Since the Japanese did not recognize the Second Geneva Convention of 1929 or the Hague Land Warfare Regulations , they treated their prisoners of war according to their own regime. Prisoners of war were considered to be without honor because they had not fallen in honor for their country, that is, they had not fought to the death. As a rule, they were therefore to be entrusted with "inferior work", which was important to the Japanese, but in their eyes could only be carried out by dishonorable people. A large number of Allied soldiers died in the Japanese prison camps due to a lack of water and food, as well as inhuman treatment.

Japanese war crimes against Allied prisoners:

- Bataan death march - around 16,000 dead

- Death Railway - approx. 16,000 Allied and approx. 100,000 Asian dead

- Sandakan POW Camp / Sandakan Death Marches - approx. 2,700 Australian and British dead

More soldiers

Polish soldiers in Soviet custody

After the USSR attacked Poland on September 17, 1939, more than 240,000 Polish soldiers were captured. Around 42,400 ordinary soldiers and NCOs were released within the first three weeks, and another 43,000 were transferred to the German Wehrmacht because they lived in the western part of Poland, which had been conquered by the German Reich during the attack on Poland .

In April 1940, between 22,000 and 25,000 career and reserve officers, policemen and other Polish citizens were shot.

Polish soldiers in German custody

Around 400,000 Polish soldiers (including around 16,000 officers) were taken prisoner by Germany. Furthermore, 200,000 Polish civilians were arrested on alleged suspicions. About 10,000 Polish prisoners of war died. The German Reich took the position that the Polish state had perished and was therefore no longer a subject of international law , and consequently the Geneva Conventions on the Treatment of Prisoners of War of 1929 did not apply to them. The Polish prisoners of war lost the protection of this convention and were only civilians from the Nazi perspective. 200,000 were then used as forced laborers who were discriminated against under the racist Poland decrees .

Italian soldiers in German custody

600,000 Italian soldiers were interned between September 1943 and May 1945. Captured Italian soldiers were murdered in the massacres on Kefalonia and Kos . The German Reich denied the soldiers of the former ally Italy the status of prisoners of war, granted them the status of military internees and used them as forced laborers. Around 45,000 Italian prisoners of war lost their lives.

Documentation and commemoration

Scientific processing

In 1957, the then Federal Ministry for Expellees founded the Scientific Commission for the Documentation of the Fate of German Prisoners of War in World War II , chaired by Erich Maschke . Between 1962 and 1974, the so-called Maschke Commission published 22 volumes, 10 of which deal with captivity in the Soviet Union.

Up to the present day the issue of prisoners of war is the subject of scientific research from the German, Western Allied and Soviet point of view, since since the collapse of the Soviet Union, especially in Eastern European archives, new research possibilities have emerged.

The Joint Commission for Research into the Recent History of German-Russian Relations also deals with the fate of Soviet prisoners of war in German hands.

The Scientific Service of the German Bundestag has produced various summaries on the topic over the years.

Exhibitions on prison conditions

In contrast to many literary testimonies, relatively little has been preserved of the camps in which the prisoners of war were housed. The finds in "Haus Molz" were more of a chance find in the course of its relocation to the folklore and open-air museum Roscheider Hof in the early 1990s. In the course of further research, it was also possible to use preserved images to prove that this house was a branch of the Trier prisoner of war camp - mainly for French prisoners of war - during the Second World War. As a result, a thematic exhibition was set up in the hall of the house in 2008. On the upper floor, the grating of the windows and the furnishing of the bedroom with beds made of raw wood for the prisoners of war were reconstructed according to old photographs.

Many recent exhibitions such as the Valentin submarine bunker (opened as a memorial in 2015) mix the subject of prisoners of war with the subject of forced laborers .

Search for former prisoners of war

The German Office (WASt) had been providing information about the fate of German Wehrmacht members and prisoners of war since 1939. After 1945, registration and research were among the main tasks of the DRK tracing service . Since 2000, the Dresden Documentation Center ( Saxon Memorial Foundation ) has been providing information on Soviet prisoners of war in German captivity. In November 2009, the Documentation Center published a database on its website that can be used to search for Soviet prisoners of war from World War II.

Artistic reception

literature

The captivity of German soldiers as prisoners of war and their return home was often dealt with in literary terms . The drama Outside the Door by Wolfgang Borchert is well known . A well-known autobiography comes from Helmut Gollwitzer , which is based on his diary entries from 1945–1950. The Association of Returnees (VdH) also published a number of testimonials.

Movie

The situation in prisoner-of-war camps during World War II was depicted in the following films (selection):

- The bridge on the Kwai

- Stalag 17

- Broken laces

- Colonel of Ryan's Express

- as far as your feet take you

- The tribunal

- Unbroken

- Trautmann

The American sitcom A Cage Full of Heroes deals - without claiming historical accuracy - with Allied prisoners of war in a German camp.

Various documentaries such as

- Love unwanted , three-part documentary film (topic: secret love affairs between German prisoners of war in France and French women).

- Captivity of war (1/4): Displaced and exploited. Production Austria 2011. Shown in 3sat on January 20, 2013, from 8:15 pm to 9:05 pm. (French and Soviet prisoners of war, forced laborers in war production, children of pregnant forced laborers deliberately disadvantaged with a high mortality rate, Soviet prisoners of war continued in Soviet camps after liberation).

- Captivity (2/4): the golden west? Production Austria 2011. Shown in 3sat on January 20, 2013, from 9:05 pm to 10:00 pm. (German prisoners of war treated in the USA according to the Geneva Convention. After the end of the war in UK, F, Soviet Union used to repair war damage).

- Captivity of war (3/4): Siberia terminus? Production by ORF and preTV 2012. Shown in 3sat on January 21, 2013, from 8:15 pm to 9:05 pm. (German / Austrian prisoners of war to the Soviet Union for forced labor).

- Captivity (4/4): homecoming. Production by ORF and preTV 2012. Shown in 3sat on January 21, 2013, from 9:05 pm to 10:00 pm. (Soviet prisoners of war and forced laborers again in forced labor and ostracism after the end of the war in the USSR. French prisoners of war suspected of collaboration in France after the end of the war. German / Austrian returnees from the Soviet Union can no longer find work in their homeland).

literature

- Kurt W. Böhme, Erich Maschke (Hrsg.): On the history of the German prisoners of war of the Second World War . Scientific Commission for German Prisoner of War History. 15 volumes. Verlag Ernst and Werner Gieseking, Bielefeld 1962 to 1974.

- Hans Coppi : Soviet prisoners of war in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In: Yearbook for research on the history of the labor movement . Issue I / 2003.

- Renate Held: Captivity in Great Britain: German soldiers of the Second World War in British custody. ed. from the German Historical Institute London . (= Publications of the German Historical Institute London. 63). Oldenbourg, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58328-1 .

- Alexander Haritonow, Klaus-Dieter Müller: The total number of Soviet prisoners of war - A question that remains unsolved. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . Vol. 58, No. 3, pp. 393-401. R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2010, ISSN 0042-5702 (PDF)

- Andreas Hilger , Ute Schmidt , Mike Schmeitzner (eds.): Soviet military tribunals (= writings of the Hannah Arendt Institute for Totalitarian Research . Volume 17). Volume 1: The sentencing of German prisoners of war 1941–1953 . Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2001, ISBN 3-412-06701-6 .

- Sophie Jackson: Churchill's Unexpected Guests: Prisoners of War in Britain in World War II. The History Press, Stroud 2010, ISBN 978-0-7524-5565-5 .

- Rolf Keller : Soviet prisoners of war in the German Reich 1941/42: treatment and labor between the politics of extermination and the economic constraints of the war. Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8353-0989-0 .

- Rolf Keller, Silke Petry (ed.): Soviet prisoners of war on the job 1941–1945: Documents on living and working conditions in Northern Germany. Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8353-1227-2 .

- Contacts contact e. V. (Ed.): I will never forget it. Letters from Soviet prisoners of war 2004–2006. Berlin 2007. (first anthology in German).

- Klaus-Dieter Müller , Konstantin Nikischkin, Günther Wagenlehner (eds.): The tragedy of captivity in Germany and the Soviet Union 1941–1956 (= writings of the Hannah Arendt Institute for Research on Totalitarianism . Volume 5). Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-412-04298-6 .

- Reinhard Otto: Wehrmacht, Gestapo and Soviet prisoners of war in German Reich territory in 1941/42. (= Series of the quarterly books for contemporary history . Volume 77). R. Oldenbourg Verlag , Munich 1998, ISBN 3-486-64577-3 .

- Rüdiger Overmans : The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. In: The German War Society 1939–1945. Volume 9, second half volume: exploitation, interpretations, exclusion. (= The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 9 / 1–2). Published by Jörg Echternkamp on behalf of the Military History Research Office . DVA , Munich 2005, ISBN 3-421-06528-4 , pp. 729-875.

- Rüdiger Overmans, Andreas Hilger, Pavel Polian (eds.): Red Army soldiers in German hands. Documents on the captivity, repatriation and rehabilitation of Soviet soldiers of the Second World War . Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2012, ISBN 978-3-506-76545-1 .

- Robin Quinn: Hitler's Last Army: German POWs in Britain. The History Press, Stroud 2015, ISBN 978-0-7524-8275-0 .

- Matthias Reiss: “The blacks were our friends.” German prisoners of war in American custody 1942–1946. Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2001, ISBN 3-506-74479-8 .

- Dmitri Stratievski: Soviet prisoners of war in Germany 1941–1945 and their return to the Soviet Union. Osteuropa-Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-940452-51-1 .

- Alfred Streim : The treatment of Soviet prisoners of war in the "Barbarossa case". A documentation. CF Müller Juristischer Verlag, Heidelberg / Karlsruhe 1981, ISBN 3-8114-2281-2 - supplement to dispute because of the strong involvement of German criminal proceedings.

- Christian Streit: No comrades. The Wehrmacht and the Soviet prisoners of war 1941–1945. Publishing house JHW Dietz. Nachf., Bonn 1997, ISBN 3-8012-5023-7 . Updated new edition of the standard work from 1978.

- Gabriele Hammermann (Ed.): Evidence of captivity: from diaries and memories of Italian military internees in Germany 1943–1945. de Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-036373-9 .

- Dmitri Stratievski: Soviet soldiers in German captivity. Human fates in personal testimonies. Anthea-Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-943583-64-9 .

- Jon Sutherland, Diane Sutherland: Prisoner of War Camps in Britain During the Second World War. Was in Britain Series. Golden Guides Press, Newhaven 2012, ISBN 978-1-78095-013-6 .

Web links

- Stefan Manners: The Demographic Dimension of Migration in Germany 1945.

- Prisoners of War: Many did not come back. In: Stern. Issue 11/2005

- POW camps: literature. in the Moosburg citizen network

- German prisoners of war in foreign custody in GenWiki

- Literature collection of the Saxon Memorials Foundation

- High Command of the Wehrmacht, orders for the treatment of Soviet prisoners of war in all prisoner-of-war camps, September 8, 1941 , in: 1000dokumente.de

- Berlin association that campaigns for the rights of former Soviet prisoners of war and publishes their memories and scientific articles on the subject

- Documentation Office Dresden: Information on Soviet prisoners of war

- Tanja Penter : Late compensation for the victims of a calculated extermination strategy in Zeitgeschichte-online , November 2015

- Help for prisoners of war in Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania . In: Resistance in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Teehaus Trebbow memorial.

- Peter Steinbach : "The bridge has been built": The confrontation of German prisoners of war with democracy in American and British captivity. In: Historical Research. Vol 22, No. 3/4, 1997, p. 277. (ssoar.info)

- ^ Rüdiger Overmans , Andreas Hilger, Pavel Polian: Red Army soldiers in German hands. Documents on the captivity, repatriation and rehabilitation of Soviet soldiers of the Second World War . Schöningh, Paderborn 2012, p. 15; See also Rüdiger Overmans: The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. In: The German War Society 1939–1945. Second half volume: Exploitation, Interpretations, Exclusion. (= The German Reich and the Second World War. Volume 9/2). Published by Jörg Echternkamp on behalf of the Military History Research Office. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2005, pp. 729–875, here pp. 799–804.

- ^ Agreement on the Treatment of Prisoners of War of July 27, 1929, RIS , accessed on October 6, 2016.

- ^ Arthur L Smith Jr.: The German prisoners of war and France 1945-1949. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . 1984, pp. 103-121.

- ↑ Control Council Proclamation No. 2. Additional demands made on Germany of September 20, 1945, Section VI, No. 19a. Verassungen.de, accessed on October 6, 2016.

- ↑ Prisoners of war as slaves. In: The time . March 24, 1949.

- ↑ Reinhart Maurach: The war crimes trials against German prisoners in the Soviet Union. Hamburg 1950.

- ↑ Barbara Brooks Tomblin: GI Nightingales: The Army Nurse Corps in World War II. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington 2003, p. 124.

- ↑ Reiss, p. 48.

- Jump up ↑ 48.

- ^ Rip 316

- Jump up ↑ 119

- ^ Rip 322

- ↑ Rip 321

- Jump up ↑ 155

- Jump up ↑ 144

- Jump up ↑ 165.

- ↑ Rip 321

- ^ Rip 282

- Jump up 99

- ↑ Georg Bönisch: Forced labor as a mine clearer: Rudi was completely riddled with holes. In: Der Spiegel. 35/2008. Online at one day on Spiegel Online , August 27, 2008.

- ↑ George Smith Patton, Martin Blumenson: The Patton Papers: 1940-1945. P. 750.

- ^ Staff, ICRC in WW II: German prisoners of war in Allied hands. February 2, 2005.

- ↑ Love undesirable. three-part documentary film: 1. Prisoner of war in France. Shown in: Phoenix on February 20, 2010, from 8:15 pm to 9:00 pm.

- ↑ all figures from Rüdiger Overmans, Die Rheinwiesenlager 1945. In: Hans-Erich Volkmann (Ed.): End of the Third Reich - End of the Second World War. A perspective review . Published on behalf of the Military History Research Office, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-492-12056-3 , p. 278.

- ^ Rüdiger Overmans: Die Rheinwiesenlager 1945. In: Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): End of the Third Reich - End of the Second World War. A perspective review . Published on behalf of the Military History Research Office, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-492-12056-3 , p. 277.

- ↑ Klaus-Dieter Müller: Soviet and German prisoners of war in the years of the Second World War : In: Vjačeslav Dmitrievič Selemenev (ed.): Sovetskije i nemeckije voennoplennye v gody Vtoroj Mirovoj Vojny / Soviet and German prisoners of war in the years of the Second World War . Saxon Memorials Foundation to commemorate the victims of political tyranny. Dresden 2004, ISBN 3-934382-12-6 , pp. 293-360, here p. 293.

-

^ Albrecht Lehmann : Captivity and Homecoming. German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union . CH Beck, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-406-31518-6 , p. 29.

Soviet Union: Don't forget anything. In: Der Spiegel . 27/1983, July 4, 1983, pp. 90-92. - ↑ Rüdiger Overmanns: The other face of the war: life and death of the 6th Army. In: Jürgen Förster (Ed.): Stalingrad. Event - Effect - Icon . Munich 1992, p. 447.

- ^ Scientific Service of the German Bundestag : German Prisoners of War in Soviet Custody 2011

- ↑ a b M. Zeidler: Stalin justice versus Nazi war crimes. 1996, p. 11 ff.

- ^ A b Manfred Zeidler : Stalin justice versus Nazi war crimes. (PDF) Hannah Ahrendt Institute for Totalitarianism Research TU Dresden, 1996, p. 34 ff. , Accessed on February 11, 2018 .

-

^ Hanns Jürgen Küsters: Moscow tour 1955 . Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung , accessed on November 17, 2015.

Eliese Berresheim: Diplomacy 1955: Adenauer's trip to Moscow was a good move. In: Welt Online . September 8, 2009. - ↑ Marc von Lüpke, Jerome Baldowski, Axel Krüger: "And then the judge read me my death sentence". In: t-online / history. t-online.de, December 30, 2019, accessed on January 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Kurt W.Böhme: The German prisoners of war in Yugoslavia. Volume I / 1 of the series: Kurt W. Böhme, Erich Maschke (Hrsg.): On the history of the German prisoners of war of the Second World War. Bielefeld 1976, ISBN 3-7694-0003-8 , pp. 42-136, 254.

- ^ Klaus Schmider : The Yugoslav Theater of War (January 1943 to May 1945). In: Karl-Heinz Frieser (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 - The War in the East and on the Side Fronts. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2 , p. 1069.

- ↑ Fred Fedorowich: Understanding the Enemy: Military Intelligence, Political Warfare and Japanese Prisoners of War in Australia, 1942-45. In: Philip Towle, Margaret Kosuge, Yōichi Kibata: Japanese prisoners of war. London 2000, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 1-85285-192-9 , p. 61. (books.google.com.au)

- ^ Brian Victoria: Zen War Stories. Routledge, 2012, ISBN 978-1-136-12762-5 , p. 106. (books.google.com.au)

- ^ Sean Brawley, Chris Dixon, Beatrice Trefalt: Competing Voices from the Pacific War. Greenwood Press / ABC-CLIO, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84645-010-5 , p. 196. (books.google.com.au)

- ↑ Fumiko Halloran: Review of the book "Japanese POWs in Siberia, Unfinished Tragedy". by Toshio Kurihara and Iwanami Shinsho. 2009, ISBN 978-4-00-431207-9 . (japansociety.org.uk)

- ^ Christian Streit: No comrades. The Wehrmacht and the Soviet prisoners of war 1941–1945. Publishing house JHW Dietz. Nachf., Bonn 1997, p. 10.

- ↑ Yad Vashem: Resistance and Struggle - Jewish Soldiers in the Allied Armies. accessed January 29, 2015.

- ↑ Andrea Grunau: Nazi crimes against Soviet prisoners of war. DW interview with historian Rolf Keller . In: Deutsche Welle. May 6, 2015, accessed June 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Reinhard Otto: Wehrmacht, Gestapo and Soviet prisoners of war in the German Reich territory 1941/42. Munich 1998.

- ↑ Rüdiger Overmans: The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. In: The German War Society 1939-1945. Second half volume: Exploitation, Interpretations, Exclusion. (= The German Reich and the Second World War. Volume 9/2). Published by Jörg Echternkamp on behalf of the Military History Research Office. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2005, pp. 729–875, here pp. 804 f.

- ↑ Timothy Snyder : Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin . CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-62184-0 , pp. 188-198.

- ↑ V. Selemenov, Ju. Zverev, K.-D. Müller, A. Haritonow (ed.): Soviet and German prisoners of war in the years of the Second World War. 2004, ISBN 3-934382-12-6 .

- ^ Hans Coppi: Soviet prisoners of war in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In: Yearbook for research on the history of the labor movement . Issue I / 2003.

- ^ WDR: Liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp: Systematic mass murder. accessed on January 29, 2015.

- ↑ Mario Bandi: The metal of war or: 100 letters from Pleskau. Deutschlandfunk , Feature , September 12, 2014. (deutschlandfunk.de)

- ^ Christian Streit: No comrades. The Wehrmacht and the Soviet prisoners of war. ( Memento from July 28, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) at: kontakte-kontakty.de , accessed on June 21, 2010.

- ↑ Miriam Dobson: Prisoners of War and Purge Victims: Attitudes Towards Party Rehabilitation, 1956–1957. In: The Slavonic and East European Review. Volume 86, No. 2, April 2008, pp. 328-345, here p. 331.

- ^ Severin Weiland: World War Memorial: Gauck recalls the suffering of Soviet prisoners of war. In: Spiegel online. May 6, 2015, accessed June 22, 2019 .

- ↑ 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. In: www.bundespraesident.de. May 6, 2015, accessed June 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Soviet prisoners of war receive compensation. In: sueddeutsche.de. May 20, 2015, accessed August 16, 2015 .

- ↑ Germany compensates Soviet prisoners of war. In: zeit.de. May 20, 2015, accessed August 16, 2015 .

- ↑ Germany compensates Soviet prisoners of war. In: handelsblatt.com. May 20, 2015, accessed August 16, 2015 .

- ↑ Michael Burleigh : The Third Reich — A New History . Hill and Wang, New York 2000, ISBN 0-8090-9325-1 , pp. 512-513 .

- ↑ Bern, PTT archive: P-00 C_0040_01 War measures, war timetable, 1939 .

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE: Second World War in Asia: When the Japanese thought they were a master race. Retrieved December 8, 2019 .

- ^ Natalia Sergeevna Lebedeva: The Deportation of the Polish Population to the USSR, 1939-41. In: Alfred J. Rieber (Ed.): Forced Migration in Central and Eastern Europe, 1939–1950. London / New York 2000, ISBN 0-7146-5132-X .

- ↑ Rüdiger Overmans: The prisoner-of-war policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. In: The German War Society 1939-1945. (= The German Reich and the Second World War. Volume 9/2). DVA, Munich 2005, pp. 729-875, here p. 755.

- ↑ Origin and number of foreign civil workers and forced laborers. Wollheim Memorial, accessed January 29, 2016.

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: judgments in Italy on compensation for victims of National Socialism are ineffective. ) AFP, February 2, 2012.

- ↑ Rüdiger Overmans: The Prisoner of War Policy of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. 2005, p. 836.

- ↑ Birgit Schwelling: Contemporary history between memory and politics. The Scientific Commission for German Prisoner of War History, the Association of Returnees and the Federal Government 1957 to 1975. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . 2008, pp. 227-263.

- ↑ K.-D. Müller: German prisoners of war. Comments on the state of research and future perspectives. In: Soviet and German prisoners of war during the Second World War. 2004, pp. 293–360, website of the Saxon Memorials Foundation , Documentation Center Dresden, accessed on October 7, 2016.

- ↑ Michael Borchard: The German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union. On the political significance of the prisoner-of-war question 1949–1955 . Univ.-Diss., Düsseldorf 2000.

- ^ Andreas Hilger: German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union 1941–1956. Everyday life in prisoners of war, camp politics and memory. University dissertation, Essen 2000.

- ↑ Alexander Epifanow, Hein Mayr: The tragedy of the German prisoners of war in Stalingrad from 1942 to 1956 according to Russian archive documents. Osnabrück 1996.

- ↑ Alexander Epifanow, Erwin Peter: Stalin's prisoners of war. Their fate in memories and in Russian archives. Graz 1997.

- ↑ Norbert Haase, Alexandr Haritonov, Klaus-Dieter Müller, Jens Nagel (eds.): Memorial book of Soviet prisoners of war. 2 volumes. Dresden 2005, ISBN 3-934382-15-0 .

- ↑ Example: German prisoners of war in Soviet custody in 2011 , others can be found using the search term

- ↑ Barbara Johr , Hartmut Roder : The bunker: An example of National Socialist madness. Bremen-Farge 1943-45 . Edition Temmen , Bremen 1989, ISBN 3-926958-24-3 .

- ^ Information on the database of Soviet prisoners of war. on: dokst.de

- ↑ Public database on Soviet prisoners of war. on: sz-online.de , November 16, 2009.

- ↑ Clarification of the fate of prisoners of war. on: goerlitzer-anzeiger.de

- ↑ A list against oblivion: The Dresden Foundation for Sächsische Gedenkstätten gives people who have been rehabilitated a name. on: mdz-moskau.eu , December 4, 2009.

- ↑ Helmut Gollwitzer: and lead where you don't want to . Frankfurt am Main 1954. With a foreword by Theodor Heuss .

- ^ Association of returnees, prisoners of war and members of missing persons in Germany (ed.): Evidence of captivity. Bad Godesberg 1962.

- ↑ in particular using the example of the three 'Russian camps' of the Wehrmacht in the Lüneburg Heath: Bergen-Belsen , Fallingbostel-Oerbke and Wietzendorf