Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March was a war crime committed in 1942 by Japanese soldiers against American and Filipino prisoners of war in the early stages of the Pacific War ( World War II ) in the Philippines .

prehistory

After the Japanese fleet attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 , the Japanese forces began invading several countries in the Southeast Asian region at the same time . This led to the invasion of the Philippines .

The Filipino and U.S. soldiers were overrun, prompting the U.S. Department of War to recall General Douglas MacArthur from the Philippines and appoint him Commander in Chief of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific. He has been replaced by Jonathan Wainwright . Around 14,000 US Marines and 2,000 Filipino tank soldiers were able to form a final nest of resistance on the Bataan Peninsula and the offshore island of Corregidor .

surrender

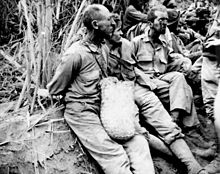

On April 9, 1942, Major General Edward P. King , who was now in command on Bataan, and around 70,000 of his troops, which consisted of Americans and Filipinos, had to surrender to the Japanese attackers under Homma Masaharu , as there was hardly any drinking water and food available stood. Some defenders were able to save themselves into the sea, where they were taken on board by an American gunboat and taken to Corregidor. Those who remained on land destroyed their ships and weapons as far as possible and fell into the hands of the Japanese. As a result, they were confronted with an unexpectedly high number of starved, sick and emaciated prisoners, which far exceeded the number of their own troops.

The march

The prisoners were forced to march north to the railway loading station at San Fernando , nearly 100 km long and six days . From there it went north to Tarlac Province to the Camp O'Donnell prison camp .

What went on during the march was later cited as one of the greatest war crimes committed by the Japanese in World War II . Since Japan had not signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, they did not feel bound by it. In addition, in the eyes of the Japanese, prisoners of war had lost their honor because they did not fight to the death like themselves. The Japanese treated their prisoners accordingly. Anyone who stopped from exhaustion or fell to the ground on the march was shot, beheaded or stabbed with a bayonet . Individual prisoners or entire troops were randomly exposed to the oriental sun treatment : They had to sit down on the floor without covering their heads and sit there for several hours in the blazing sun. Anyone who fell over was killed. The whole day had to be marched. Those who did not keep to the set pace were harassed by the guards to go faster. At night, the prisoners could lie down in the open field. A wake-up call came early in the morning and the trek moved on.

During the whole march there was hardly any food or water from the Japanese. Locals who tried to give the prisoners food were shot. As the train passed a river, many soldiers ran to the fresh water. All of them were shot. Only for the last two days did the guards hand out rice balls , one for each man per day.

While the prisoners supported each other at the beginning, for example by laying sick and injured people in blankets and being carried on by comrades, towards the end it was all about survival for everyone. It happened that the last American bastion on Corregidor began to fire grenades at Bataan. Many of the marchers fell victim to their own fire.

Diseases such as malaria and dysentery began to spread among the prisoners . Many fell victim to dehydration and hunger. Of the original 66,000, only just under 54,000 reached the destination. The survivors of the death march were used for forced labor . After the war ended, only 15,000 GIs returned to the US.

Aftermath

On June 6, 1942, the Japanese occupying forces pronounced an amnesty against the Filipino prisoners and released them. The American soldiers were transferred to the Cabanatuan prison camp in Nueva Écija province .

After some time in this camp, the captured soldiers were loaded onto eleven ships that were later referred to as ships of hell . They were supposed to take the prisoners to Busan , Korea . The soldiers had to spend 33 days cooped up on board during the crossing. Dutch submarines , whose crews did not know about the prisoners of war on board, attacked the ships and sank six of them.

After the war ended, an American court martial sentenced Japanese commander Homma Masaharu to death for serious war crimes . It could not be determined whether he had given direct orders for abuse. At least he tolerated the inhumane acts of his subordinates and did not stop them. Homma was executed outside Manila on April 3, 1946 .

memory

In Barangay O'Donnell (municipality Capas ) in 1991 by the Philippine president was Corazon Aquino , the national memorial Capas National Shrine (Capas Paggunita Sa) inaugurated. It commemorates the death march of the American and Filipino soldiers in 1942. Every year on April 9, a memorial service is held in honor of the dead.

In addition, the Bataan Memorial Death March has been held annually on the White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) since 1989 . In commemoration of the death march, the participants cover a distance of 26.2 miles (42.16 km - Green Route) and 14.2 miles (22.85 km - Blue route) in different categories (civil, military, with and without luggage) Route) back on foot through the dusty and dry and hot desert of New Mexico, overcoming approx. 550 positive vertical meters.

Filipino director Adolfo Alix Jr. made a war film about the death march from Bataan entitled Death Marsh , which was shown in the 2013 Cannes Film Festival in the Un Certain Regard section .

literature

- James Bollich: Bataan Death March: A Soldier's Story. Pelican Publishing Company, 2003, ISBN 1-58980-167-9 .

- Wm. E. Dyess, Charles Leavelle, Stanley L. Falk: Bataan Death March: A Survivor's Account. University of Nebraska Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8032-6633-2 .

- Kristin Gilpatrick: Footprints in Courage: A Bataan Death March Survivor's Story. Badger Books, 2002, ISBN 1-878569-90-2 .

- Joseph Quitman Johnson: Baby of Bataan: Memoir of a 14 Year Old Soldier in World War II. Omonomany, 2004, ISBN 1-59096-002-5 .

- Donald Knox: Death March: The Survivors of Bataan. Harvest / HBJ Book, 2002, ISBN 0-15-602784-4 .

- Michael and Elizabeth M. Norman: Tears in the Darkness. The Story of the Bataan Death March and its Aftermath. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2009, ISBN 978-0-374-27260-9 .

- Hampton Sides : The Ghost Squad. 1945 in the jungle of Asia: the story of a highly dramatic rescue operation. Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-442-15189-9 .

- Lester I. Tenney: My Hitch in Hell: The Bataan Death March. Brassey's Inc, 2000, ISBN 1-57488-298-8 .

Web links

- Bataan, Corregidor, and the Death March: In Retrospect ( Memento of July 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- Project page by Elizabeth Marie Himchak ( Memento from October 16, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- A survivor of the death march reports (English)

- Bataan Memorial Death March (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ US prisoners of war had to build kamikaze planes , welt.de, July 16, 2015

- ↑ Prisoners of War: Unbearable Sufferings , Spiegel Online , July 16, 1984

- ↑ The Second World War. GEO Epoche Panorama, No. 6, Hamburg 2015, p. 71.

- ↑ Bataan's death march nominated in Cannes In: Euronews , accessed on May 27, 2019.

- ↑ Joachim Kurz: Death March. In: kino-zeit.de. May 20, 2013, archived from the original on October 11, 2013 ; accessed on November 3, 2019 .