Siemens warehouse in Ravensbrück

The Siemens Ravensbrück was a part of the camp complex of concentration camp (KZ) Ravensbruck in the era of National Socialism . It was built from 1942 in the municipality of Ravensbrück (today the city of Fürstenberg / Havel ) in the north of the province of Brandenburg . Female inmates did forced labor for Siemens & Halske (S&H) there.

Planning and construction

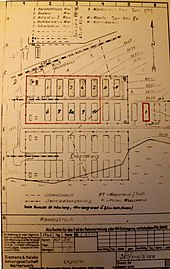

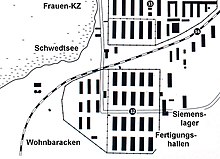

In 1942, foreign forced laborers and prisoners from the concentration camps were to be included in the war economy in order to replace the employees who were called up to the front. From the beginning of 1942 the director of the Wernerwerke, Gustav Leifer, and Friedrich Heinrich Lüschen conducted negotiations with the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Reich Ministry of Aviation on the deployment of concentration camp prisoners . From 1942 to 1944 Siemens & Halske, in cooperation with the SS and the Reich Aviation Ministry, built ten work barracks, each with an area of 675 m² and siding, in a fenced area south of the main camp of the Ravensbrück concentration camp. In these work barracks, female inmates were supposed to do forced labor. The area was bordered to the west and south by the Schwedtsee and the Havel , to the east was a forest area and the Uckermark youth concentration camp . The Siemens camp was to become a model for the deployment of concentration camp prisoners in the war economy. In arms production it was the first time prisoners were deployed directly on a concentration camp site.

The Reich Ministry of Aviation was responsible for the construction of the buildings and all connections with electricity, telephone and water, while Siemens & Halske was responsible for furnishing the buildings and workshops. The work barracks were built by prisoners from the men's camp of the Ravensbrück concentration camp. An expansion of the camp, which was realized in 1943, was already taken into account on the construction drawing for planning the first ten work barracks. At the construction meeting between the Reich Aviation Ministry and Siemens & Halske on April 16, 1942 in Berlin-Siemensstadt, it was agreed that Siemens & Halske would pay the concentration camp management a maximum rent of two Reichsmarks per m² per month. At the end of 1944, around 2500 women and girls were producing components for Siemens- Wernerwerke in the Siemens warehouse .

production

The Siemens operating part Wernerwerk für Fernsprechgeräte (WWFG) started its activity on August 24, 1942 with 20 prisoners (according to another source with 50 prisoners). In a fenced-in barrack, adjustment work was carried out by predominantly German women with black angles as a sign of " anti-social ". In September there were 300 women; By December 1942, around 500 women and girls were employed, and in 1944 over 2000, mainly for winding coils and building relays and telephones.

Prisoners from abroad were increasingly used in production, while German and Austrian prisoners mainly worked in administration. In 1943 more barracks were set up. In October 1944, the Werner factory for measuring devices was relocated here from Metz and in December an ultra-modern electroplating and paint shop was added.

Finally, in the Siemens camp there was the Wernerwerk for telephones with six production barracks , the Wernerwerk for radios with five production barracks and the Wernerwerk for measuring devices with five production barracks. A total of 20 barracks existed for production and shipping, as well as eight, according to other sources, 13 residential barracks for women and girls.

These residential barracks were set up right next to the work barracks at the end of 1944 and the inmates moved into on December 3, 1944. This improved the quality of the products and increased the quantity . At that time, around 80 civilian workers and around 2,400 prisoners were engaged in war-related work in the Siemens camp. It mainly concerned the winding of coils, the production of microphones and electrical switching parts, primarily for air armament. In an effective division of labor with other Siemens factories, the Siemens warehouse in Ravensbrück assumed more and more tasks. The entire production of field telephones was relocated to Ravensbrück. Electrotechnical components for submarines and from 1944 for the V2 rocket program were also produced here . In the neighboring Uckermark youth concentration camp for girls and young women, 100 girls also produced components for Siemens & Halske in two work barracks.

Forced laborers and working conditions

The age of the inmates was between 17 and 48 years. In order to select suitable women, the concentration camp prisoners had to pass a skill test and intelligence test. Since many jobs required good eyesight, visual acuity was determined. In addition, a wire had to be bent into a certain shape and a piece of paper folded according to the prescribed scheme. As in the Siemens works, the work was organized with civilian workers.

The Siemens company paid the SS the monthly rate of initially two and later three or four Reichsmarks for each prisoner deployed. There was a wage scale, as more was paid for skilled workers. The work performed was entered on the wage slips of the individual concentration camp inmates. In addition, the resulting wage (around 40 pfennigs per hour), which corresponded to that of Siemens workers. However, the women in the Siemens camp did not receive this wage. Despite the inadequate nutrition, the prisoner women achieved about the same average performance after an induction phase during the eleven hours of work as the piece workers in Berlin during an eight-hour day. Even high-ranking Siemens representatives from a commission from Berlin were amazed.

These pay slips were used, among other things, to check whether the workload was completed. If the workload was not reached, the master gave a sermon. In the event of a repetition, the SS guard was called in, who distributed "slaps" and wrote a "report" which then led to the punishment block or "bunker". As an incentive for good work, there was an additional slice of bread or sausage, and if the workload was overworked, there were bonuses in the form of fifty-pfennig or one-mark vouchers, which could be redeemed in the prisoner's canteen for salt and fish paste. From 1943, after work, the inmates were shown cultural films as a reward.

According to eyewitness reports, the work in the Siemens camp was the best one could endure compared to the other occupations in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. The high, spacious work barracks were very bright due to the many large windows. Each concentration camp inmate sat at their own workplace, which was also illuminated with strong electric light. Here coils were wound, checked and adjusted, assembly work was carried out and switches and telephones were manufactured. Relays for self-dial telephones and bomb drop devices were assembled, tested and packed. In November 1942 the daily working time was increased from eight hours for Monday to Friday to 10.75 hours and for Saturday to nine hours. Night shifts lasting 10.5 hours were also introduced. The working time in the Siemens camp was initially 48 and from November 27, 1943 by order of the SS 62.2 hours per week.

Construction and occupation of residential barracks next to the work barracks

Initially, the prisoners came from the main camp on foot. Especially in the cold seasons they were hypothermic due to the previous roll calls of up to two hours and the division of the work columns by the SS and the march to the Siemens camp with insufficient clothing and shoes, mostly wooden shoes . Only after a long “thawing time” were they able to carry out the demanding work required in the Siemens warehouse, such as winding coils with very thin insulated wires. At noon the march back to the main camp took place. Since the lunch break from 11:45 a.m. to 12:45 p.m. was too short due to the line-up, controls by the SS and the way to the main camp, the prisoners were often no longer given any food.

That was one of the reasons to set up residential barracks and a kitchen (for residential barracks, see the map of the Siemens camp in Ravensbrück). The other reason was the planned provisional gas chamber and crematorium, which the inmate women would have passed four times a day on the way to the Siemens camp. Six residential barracks that were larger than in the women's camp were set up in the Siemens camp. These barracks were each divided into three rooms and initially there was a separate bed for each prisoner. The residential barracks were secured with a double barbed wire fence and four watch towers.

On December 3, 1944, the approximately 2,100 women prisoners in the Siemens camp moved to the small residential camp west of the company on the Siemens premises. A quieter time began there. The roll calls now only lasted a few minutes and the food was much better than in the main camp. As in the main camp, however, the hygienic conditions with the 32 washing stations and a large outdoor latrine were catastrophic.

Including the Siemens camp in Ravensbrück, a total of 54,000 women and 17,000 men from the Ravensbrück concentration camp had to do forced labor for the SS, business, armed forces and the state in many satellite camps.

Organization of the Siemens warehouse

The Siemens camp was administered by the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office in Oranienburg, the SS supervised and punished the women in the concentration camp and the work instructions were given by the Siemens civilian workers.

Administration by the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office

The Ravensbrück concentration camp and the Siemens camp, like all concentration camps and satellite camps, were centrally administered by the SS Economic Administration Main Office (WVHA). In all concentration camps, the WVHA organized the SS's own satellite camps, industries, trades and businesses (for example Texled, which was founded in 1939 in the Ravensbrück concentration camp) and brought them together to form groups of their own.

The WVHA, founded in March 1942 by SS-Obergruppenführer Oswald Pohl , operated the economic exploitation of prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners through the main office of administration and economy. In 1943/44 there were more than 40,000 concentration camp prisoners who, like in the Siemens camp, had to work in around 30 companies with over 100 factories and who belonged to the economic empire of the SS. From 1944 onwards, the WVHA had set up a central concentration camp prisoner index that was supposed to record all prisoners in the concentration camp system. The WVHA was subordinate to the SS main office. The punch card system from Deutsche Hollerith-Maschinen Gesellschaft mbH ( DEHOMAG ), a subsidiary of IBM, was used for recording . Among other things, this was intended to control the work of the concentration camp prisoners centrally. Oswald Pohl was sentenced to death in the Nuremberg Trial and executed in 1951.

Supervision by SS and guidance and control by Siemens employees

The camp was under the command of SS Hauptscharführer Grabow. From August 1942, production was managed by Siemens & Halske employee Otto Grade. From 1943, Siemens board member Gustav Leifer was responsible for the Ravensbrück production site, among other things. Leifer committed suicide on April 25, 1945. The women in the concentration camps served as replacements for the Jewish workers in Berlin-Siemensstadt, who had to do forced labor here in Siemens factories until they were deported to ghettos and extermination camps.

Shortly after the Siemens camp was established, Margarete Buber-Neumann became the secretary of camp manager Grade, as she mastered shorthand and typewriter as well as the Russian language. Among other things, she conducted the correspondence between Grade and the management of the concentration camp. In October 1942, the Siemens camp was inspected by the concentration camp administration, including the SS superintendent Johanna Langefeld . She made sure that Buber-Neumann came to her office, and in the spring of 1943 Margarete Buber-Neumann was the personal secretary of the SS superintendent Langefeld.

At the end of 1942, around 280 women prisoners were working in the Siemens camp; in February 1945 there were around 2,300 women prisoners, as the table from Bernhard Strebel shows : The Ravensbrück concentration camp . The number of SS guards (1:70 to 1:85) and the number of Siemens employees referred to as civilian workers was dependent on the number of prisoner women.

| Wernerwerk | Aug 1942 | Apr 1943 | Oct 1944 | Dec 1944 | Feb 1945 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for telephones | - | - | 981 | 953 | 954 |

| for radios | - | - | 714 | 762 | 802 |

| for measuring instruments | - | - | 390 | 473 | 542 |

| total | 19-28 | 348 | 2085 | 2188 | 2298 |

The prisoners were instructed and controlled by around 150 civilian foremen, fitters and foremen (civilian workers), who in turn were subordinate to masters from the Siemens works. The civil workers lived in barracks near the factory halls within the area guarded by the SS guard chain.

The SS was responsible for supervision. In Ravensbrück, the superintendent was directly subordinate to the commandant, who was on the same level as the protective custody camp leader. Carrying out the daily roll calls for women in the concentration camps and setting up internal and external work details (as in the Siemens camp) were among their most important tasks. The assignment of around 150 female guards as block leaders and guarding the work details were other tasks.

SS-Oberaufseherin Christine Holtöver was charged in the seventh Ravensbrück trial with six women guards of mistreating Allied prisoners and selecting prisoners for the gas chamber. The trial lasted from July 2 to July 21, 1948, and Christine Holtöver was acquitted for lack of evidence.

The SS supervisor Hertha Ehlert was initially responsible for supervising the Siemens column (until October 1942). She was good-natured, rarely reported prisoners and inconspicuously gave the constantly hungry prisoners food. As a result, she was exchanged for a stricter guard and given a sentence. The way from the Ravensbrück concentration camp led past the pigsty and the nursery over the rails to the Siemens camp. The crematorium built outside the camp walls (1944) and the temporary gas chamber of the concentration camp were later located on the way. The SS supervisors were not members of the SS. They were considered members of the " SS entourage ", but were subject to SS jurisdiction. From the beginning of 1942, the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp served as a central training camp for new SS guards who were later transferred to other concentration camps or satellite camps.

Dissolution and further use of the Siemens warehouse

From the beginning of 1945, the supply of materials kept stagnating, and from April 1945 the shortage of materials became so great that production could no longer be carried out. On the night of April 13-14, the Siemens camp was evacuated by order of the camp management. The remaining women and girls from the Siemens camp had to go back to the main camp as one group on the orders of the SS. The Siemens workers dismantled the machines and dismantled them for transport by water and land.

The barracks were occupied by male prisoners from arriving deportation transports , mainly men from the evacuated Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp . The main camp was now completely overcrowded, as the German extermination camps in eastern Central Europe were evacuated and inmates were distributed to camps in Germany.

Remains of the camp

Today only the foundations of the Siemens warehouse can be seen. There are no more buildings from the time of National Socialism . The area was used by the Soviet Army after 1945 ; The few remaining buildings and garages on the site date from this time. After that there was hardly any public activity at the Siemens camp and entry was forbidden.

In 2013, the Ravensbrück memorial and memorial opened the new permanent exhibition The Ravensbrück Women's Concentration Camp - History and Remembrance in the renovated headquarters in the presence of surviving concentration camp inmates . It gives a comprehensive insight into the development of the concentration camp, the Siemens camp and the Uckermark youth protection camp. On the 2nd floor, a room on the Siemens warehouse was furnished with a few display boards, photos and various documents, and a field telephone from the Siemens & Halske company from that time was also exhibited.

Refurbishment by Siemens

As documented in Forced Labor under National Socialism , Siemens paid seven million DM to Jewish forced laborers in 1962 on the basis of an internal company report from 1945 submitted to the Jewish Claims Conference .

The Werner von Siemens vocational school of Siemens Professional Education Berlin (SPE) launched the siemens @ ravensbrück project in cooperation with the Ravensbrück memorial and memorial site and the Berlin works councils of Siemens AG . As part of the project, which has been running every year since 2010, some students have the opportunity to meet surviving women from the Ravensbrück concentration camp, some of whom, like Selma Velleman from the Netherlands , did forced labor in the Siemens camp. The five-day stay gave them the opportunity to visit the concentration camp, some of which still existed, the exhibition and the remains of the Siemens camp.

Processing by concentration camp inmates

Former inmates of Ravensbrück had sought compensation against Siemens, which was rejected due to the statute of limitations.

Some of the surviving concentration camp inmates compiled reports of their experiences and made them available to the public. This happened either through the contemporary witnesses themselves or through initiatives and schools.

One example is the very detailed description of Erna Korn, born in Kaiserslautern in 1923 (after Erna de Vries married ), who voluntarily accompanied her mother to the concentration camp and after her mother's death in the Ravensbrück concentration camp until it was closed on April 15, 1945 in the associated camp Siemens warehouse Ravensbrück worked. Since 1998 Erna de Vries has been attending schools and educational establishments and telling young Germans her story. With this, Erna de Vries fulfills her mother's mission: “You will survive, and then you will tell what they did to us.” In March 2006 the brave woman received the Federal Republic of Germany's Medal of Merit.

Anna Vavak was sent to the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp in 1942. At that time, inmate women were selected for the Siemens camp in Ravensbrück. Anna Varvak wanted to get in touch with the civilian workers and she volunteered for the armaments factory outside the concentration camp. She was soon working in the Siemens work office, gained insight into important processes and later reported on them in detail.

Selma Velleman , born on June 7, 1922, was Dutch and had Jewish roots and helped the Dutch resistance to hide Jewish families. In June 1944 she was arrested in Utrecht, interrogated in the Amsterdam prison and taken to the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp, which was totally overcrowded at the time, where she was severely mistreated. She worked eight months in the Siemens camp, was liberated by the Swedish Red Cross on April 23, 1945 and came to Stockholm via Denmark and Malmö.

Margrit Wreschner-Rustow was born Marguerite Wreschner in Frankfurt / Main in 1925, grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family and was arrested in the Netherlands. She and her family were deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where they performed forced labor in the Siemens Ravensbrück camp. She and her sister survived and she extensively documented her time in the Ravensbrück concentration camp.

Eva Hesse , a Jew born in Cologne in 1902, had been interned in the Ravensbrück concentration camp since early 1943 and had to do forced labor in the Siemens Ravensbrück camp since the summer of 1944. During night shifts she had to wind capacitors and work on the assembly line. On smuggled work slips from Siemens, she secretly jotted down over 100 recipes from camp inmates from 15 countries. In times of greatest deprivation and hunger, the women captured in the Ravensbrück concentration camp remembered their favorite dishes from home, which Eva Hesse secretly noted down and smuggled out of the camp. After the Second World War , she emigrated to the USA. In the course of working on the publication of the cookbook, she gave the journalist Dagmar Schröder-Hildebrand numerous interviews , from which the author Eva Hesses-Ostwalt's life story in “I'm dying of hunger!” Wrote recipes from the Ravensbrück concentration camp . In 2008 her life story was filmed in America by the American documentarist Michael Marton on behalf of the WDR in the 45-minute film Lust am Leben - At 103 . In the same year, the 60-minute documentary To Live, What Else! about the life of Eva Hesse-Ostwalt, who fought for compensation for forced labor in the Siemens camp in Ravensbrück until old age. In 1999, at the age of 97, she received compensation from the Siemens Humanitarian Relief Fund for Forced Laborers .

literature

- Eugen Kogon : The SS state. The system of the German concentration camps . Nikol, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-86820-037-9 (first edition: 1946).

- Alyn Beßmann, Insa Eschebach (Hrsg.): The women's concentration camp Ravensbrück: history and memory . Exhibition catalog (= series of publications by the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation . Volume 41 ). Metropol-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-122-3 .

- Margarete Buber-Neumann : As prisoners with Stalin and Hitler . 2nd Edition. Seewald Verlag, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-512-00440-7 .

- Silke Schäfer: On the self-image of women in the concentration camp. The Ravensbrück camp. Berlin 2002 (Dissertation TU Berlin), urn : nbn: de: kobv: 83-opus-4303 , doi : 10.14279 / depositonce-528 .

- Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 .

Web links

- Bärbel Schindler-Saefkow: Siemens & Halske in the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp . Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, May 2000.

- Siemens Ravensbrück project . Werner von Siemens Vocational School - independent school from Siemens AG.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Silke Schäfer: On the self-image of women in the concentration camp. The Ravensbrück camp. Berlin 2002 (Dissertation TU Berlin), urn : nbn: de: kobv: 83-opus-4303 , doi : 10.14279 / depositonce-528 , p. 67

- ^ Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 386 .

- ↑ Alyn Beßmann, Insa Eschebach (ed.): The women's concentration camp Ravensbrück: history and memory . Exhibition catalog (= series of publications by the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation . Volume 41 ). Metropol-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-122-3 , pp. 180 .

- ↑ Margarete Buber-Neumann : As prisoners with Stalin and Hitler . 2nd Edition. Seewald Verlag, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-512-00440-7 , p. 226 .

- ↑ Bärbel Schindler-Saefkow: Siemens & Halske in the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp. (PDF) UTOPIE Kreativ, issue 115/116, 2000, accessed on October 18, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Jens Wiesner and Jan Telgkamp: The Siemens warehouse in Ravensbrück. (PDF) project slow motion e. V. , accessed on October 18, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c Alyn Bessmann, Insa Eschebach (ed.): The women's concentration camp Ravensbrück: history and memory. Exhibition catalog (= series of publications by the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation . Volume 41 ). Metropol-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-122-3 , pp. 184 .

- ^ Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 405 .

- ^ A b c Siemens Ravensbrück project: Working conditions. Werner-von-Siemens-Werkberufsschule - Independent School of Siemens AG, 2010, accessed on September 20, 2015 .

- ↑ Alyn Beßmann, Insa Eschebach (ed.): The women's concentration camp Ravensbrück: history and memory. Exhibition catalog (= series of publications by the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation . Volume 41 ). Metropol-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-122-3 , pp. 185 .

- ↑ a b Silke Schäfer: On the self-image of women in the concentration camp. The Ravensbrück camp. Berlin 2002 (Dissertation TU Berlin), urn : nbn: de: kobv: 83-opus-4303 , doi : 10.14279 / depositonce-528 , p. 68.

- ↑ a b Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 408 .

- ↑ Eva Meschede: Model trial for forced labor: Justice, statute-barred. Waltraud Blass against Siemens: after 45 years still no wages. Die Zeit , August 31, 1990, accessed October 19, 2015 .

- ↑ a b Margarete Buber-Neumann : As prisoners with Stalin and Hitler . 2nd Edition. Seewald Verlag, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-512-00440-7 , p. 230 .

- ↑ Alyn Beßmann, Insa Eschebach (ed.): The women's concentration camp Ravensbrück: history and memory. Exhibition catalog . Series of publications by the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation , vol. 41. Metropol-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-122-3 , pp. 129 .

- ↑ Alyn Beßmann, Insa Eschebach (ed.): The women's concentration camp Ravensbrück: history and memory . Exhibition catalog (= series of publications by the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation . Volume 41 ). Metropol-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-122-3 , pp. 128 .

- ↑ [1] , move to the residential camp, accessed on October 7, 2019

- ↑ Alyn Beßmann, Insa Eschebach (ed.): The women's concentration camp Ravensbrück: history and memory . Exhibition catalog (= series of publications by the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation . Volume 41 ). Metropol-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-122-3 , pp. 187 .

- ↑ Margarete Buber-Neumann : As prisoners with Stalin and Hitler . 2nd Edition. Seewald Verlag, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-512-00440-7 , p. 229 .

- ^ Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 402 .

- ^ Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 395 .

- ^ Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 394 .

- ^ Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 398 .

- ↑ a b c Silke Schäfer: On the self-image of women in the concentration camp. The Ravensbrück camp. Berlin 2002 (Dissertation TU Berlin), urn : nbn: de: kobv: 83-opus-4303 , doi : 10.14279 / depositonce-528 , p. 69.

- ↑ Margarete Buber-Neumann : As prisoners with Stalin and Hitler . 2nd Edition. Seewald Verlag, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-512-00440-7 , p. 229 .

- ^ Bernhard Strebel: The Ravensbrück concentration camp . 1st edition. Ferdinand Schöningh, 2003, ISBN 3-506-70123-1 , p. 418 .

- ↑ Peer Heinelt: Compensation for Nazi Forced Laborers. (PDF) wollheim memorial, p. 24 , accessed on October 4, 2015 .

- ^ Project Siemens Ravensbrück. Werner-von-Siemens-Werkberufsschule - Independent School of Siemens AG, 2010, accessed on September 20, 2015 .

- ↑ A century of will to live . In: Der Tagesspiegel Online . March 25, 2008, ISSN 1865-2263 ( tagesspiegel.de [accessed April 24, 2018]).

- ↑ Dagmar Schroeder-Hildebrand: I'm dying of hunger! : Recipes from the Ravensbrück concentration camp . Donat, Bremen 1999, ISBN 3-931737-87-X , p. 237 .

- ↑ Eva Oswalt papers. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed April 24, 2018 .