Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (initially often referred to as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Research ) was an institute of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science in Berlin-Dahlem, founded in 1917 . While the institute initially only served financial research funding , it was expanded into an independent research institute in the 1930s . During the Second World War , employees of the institute were significantly involved in research on the German uranium project. According to the formulation of the science historian Horst Kant"It remained a certain curiosity for almost 20 years (after it was founded)" because apart from the director and his deputy it had no scientific staff and the "institute address (...) was the private address of the director". With the transfer of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes to the Max Planck Society in 1948, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics became the Max Planck Institute for Physics , from which several other Max Planck Institutes emerged in the course of its history .

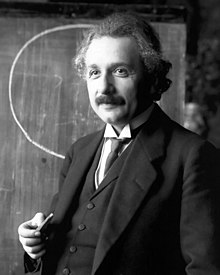

After Albert Einstein (director 1917 to 1933), directors of the institute were Peter Debye (1935 to 1940) and Werner Heisenberg (from 1942).

founding

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science was founded on January 11, 1911 with the aim of founding non-university research institutions dedicated exclusively to basic research. While the state bore the salaries of the scientists and employees, the individual institutes were mostly financed by private foundations.

When it was founded, it was agreed that the institutes of the society should also include an institute for physical research. Since there were already three research institutions in Berlin with the physics institutes of the university and the technical university as well as the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (PTR) founded in 1887 , the establishment of a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics was made however, initially not classified as of the utmost urgency.

When the banker Leopold Koppel , who had already made generous donations available for the establishment of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, agreed to grant funding for physical research as well, Max Planck , Walther Nernst , Fritz Haber , Heinrich Rubens and Emil Warburg founded a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for physical research at the Senate of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in early 1914. They suggested that the institute should only have a small building available in which there should be the possibility for meetings as well as space for an archive, a library and a warehouse for physical equipment. The aim of the facility was to give scientists from various fields and various institutions the opportunity to meet for a limited period of time in order to work together on a specific scientific question. Compared to a conventional institute with a permanent staff, it was hoped that this would not only save costs but also have a stimulating effect on scientific work. Albert Einstein was proposed as director of the institute .

On July 27, 1914, one day before the outbreak of the First World War, Finance Minister Hermann Kühn refused to provide the funds for the state's necessary one-third stake in the institute. A few years later, however, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society was able to raise the funds that were lacking due to the refusal of state funding itself through a donation from the Berlin manufacturer Franz Stock amounting to 500,000 marks. The Senate of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society decided on July 6, 1917 - in the middle of the First World War, to found the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for physics on October 1, 1917.

In addition to Albert Einstein, whose position was initially designated as Permanent Honorary Secretary and only later as Director, the Board of Directors also included the five scientists who had signed the founding application. The institute's board of trustees consisted of representatives from the government, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and several representatives from the Koppel Foundation .

The institute under Albert Einstein

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics did not initially have its own institute building; the address of the institute was Albert Einstein's private address at Haberlandstrasse 5 in Berlin-Schöneberg . Scientists were able to apply to the institute for financial support for the purchase of apparatus and equipment as well as grants for the performance of certain physical investigations. It was the task of the board of directors to examine the applications received and then to make a recommendation to the board of trustees, which ultimately decided on the financial allocations. The only criterion for awarding the funds was the revival of physical research, which had come to a complete standstill during the First World War.

The equipment and instruments acquired through financial support from the institute remained the property of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, which later loaned them to other scientists if required. By skillfully using the available resources, the institute made it possible to work on numerous basic physical questions at various institutes, so that it was able to make a significant contribution to physical research in the post-war period. The original idea that scientists from different research institutions should come together in the institute in order to work on certain scientific questions together for a limited time, however, was never realized, probably also because Albert Einstein, as director, was not very interested in the associated increase in administrative work .

In the period between 1918 and 1920, the astronomer Erwin Freundlich , who was working on the examination of general relativity , was the institute's only research assistant.

In 1921 Max von Laue was elected to the directorate of the institute, who was appointed deputy director a short time later. Einstein, who from October 1922 to the beginning of 1923 undertook a lecture tour to the Far East, to China and Japan, Palestine and finally Spain and who had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics for 1921 on November 9, 1922 , gradually left him the management of the institute. While Einstein, as director, received a salary of 5,000 marks per year, Laue, who was a full professor at the University of Berlin, received no salary for his work at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics.

The funds available to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics shrank due to inflation . In 1920 the Emergency Association of German Science was founded, which increasingly took on the task of financial research funding. As a result, the importance of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics as a funding institution for physical research steadily decreased in the course of the 1920s.

So that the institute could continue to be of use to basic physical research, on von Laue's initiative, the board of directors submitted an application in 1927 for the establishment of a Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for theoretical physics, which would be achieved by expanding the existing Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics should be implemented. In the application, the directorate stated that theoretical physics is dependent on experimental facilities that were not available at the other physical institutes in Berlin. However, since the Kaiser Wilhelm Society lacked the necessary financial resources at this point in time, the application had to be rejected first.

In November 1929 the board of directors, in which Erwin Schrödinger was now represented as Emil Warburg's successor, made another attempt via the Berlin Academy. Emil Warburg's son, the biochemist Otto Warburg , who had worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin-Dahlem since 1918, received an offer from the Rockefeller Foundation to finance his own institute for cell physiology in Germany while on a lecture tour in the USA. Since Warburg expected a great advantage for his own research work from a close collaboration with scientists from the field of physics, he advocated that part of the money provided was used for the planned Institute for Physics.

Einstein, who himself was not interested in the position of director of the new institute, urged von Laue to take on this task. However, necessary budget cuts in the Kaiser Wilhelm Society meant that it was unable to cover the running costs, so that the establishment of the institute had to be postponed first. Max Planck, who had been President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society since July 1930, and the physicists of the university institute aimed for close collaboration between the newly founded institute and the university institute for physics on the Reichstagufer, which is why they agreed that after When Walter Nernst retired as full professor of physics at the Berlin University in 1933, the two director positions should be filled by a single person. While Planck favored James Franck , Hans Geiger from Tübingen and Otto Stern from Hamburg were on the appointment list of the University .

The Nazi takeover of power in January 1933 ruined these considerations, James Franck and Otto Stern, both of Jewish descent, emigrated to the USA, as did Albert Einstein. Max von Laue turned down the position as director in view of the changed political circumstances. Planck then offered the post of director to Professor Peter Debye from Leipzig, who had been rejected in 1932 as Walter Nernst's successor on the grounds that his field of theoretical physics at Berlin University was already occupied by other scientists. In Debye, Planck, who foresaw the future importance of atomic research, saw the most suitable scientist for the position of director at the new physics institute.

An objection from the President of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt Johannes Stark , who tried not to let theoretical physics become too strong, delayed Debye's appointment, but ultimately could not prevent it. Debye only found out in December 1933 that the post of director at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was also linked to the physics professorship at the university. Since he had hoped, freed from the obligations of a professorship, as director of the institute to devote more time to research, and also insisted on being able to keep his Dutch citizenship, the appointment negotiations finally dragged on until the end of 1935. Debye was finally appointed director of the institute and professor at the university in March 1936 with retroactive effect from October 1, 1935.

The institute building

As early as 1930, a plot of land in the immediate vicinity of Otto Warburg's Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Cell Physiology in Berlin-Dahlem was planned as a building site for the institute. After the Rockefeller Foundation had promised to pay out a sum of $ 360,000 in 1935, construction of the new institute building began in 1936. The research work could already be started in the spring of 1937, the official handover of the keys to Peter Debye took place on May 30, 1938 during the 27th general meeting of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in Dahlem.

Even before the negotiations with the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, Debye had agreed to hold a visiting professorship in Liège from October 1934 to April 1935 . After his return he took an active part in the construction planning for the institute, supported by his assistant from Leipzig Ludwig Bewilogua . It was important to him that the laboratories were equipped in such a way that they were suitable for scientific experiments in as many areas of physics as possible. In accordance with the planned future research focus of the institute in the field of nuclear physics as well as work in the low temperature range near absolute zero , he also provided special structural equipment. At the west end of the main wing, an approximately 20 m high tower with a diameter of 15 m, which was later often referred to as the “tower of lightning”, was built in which a high-voltage system from Siemens & Halske was housed. This facility, which was financed by the German Research Foundation and is unique in Germany, was intended to investigate atomic conversion processes. In addition, a refrigeration laboratory was set up, which was separated from the main building for safety reasons and in which liquid air and liquid hydrogen could be produced from mid-1937. After the completion of a second expansion stage, temperatures below the helium temperature could also be generated here at the end of 1938 using magnetocaloric processes .

In the run-up to the opening, there were disputes about the naming of the new institute. Based on the Harnack House , the society house of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, some senators had suggested that the new institute be named "Max Planck Institute" in honor of the Society's president. The Reich Minister for Science, Education and Public Education Bernhard Rust only found out about this project in May 1937 through a protest submitted by Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark, saw it as an affront to party politics and protested against the nomination. Since representatives of the Rockefeller Foundation were also present at the inauguration of the institute in 1939, Rust was no longer able to intervene publicly, so that the institute was publicly named the Max Planck Institute . This name was written in large letters above the entrance to the institute, while the official name of Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics was engraved on the plaster next to the door .

The institute under Peter Debye

In addition to Peter Debye as director, Max von Laue as his deputy and Hermann Schüler , head of the spectroscopic department , two other professors were employed at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute . In addition, six scientific assistants and a team of technical staff worked here with Ludwig Bewilogua , Wilhelm van der Grinten, Wilhelm Ramm, Friedrich Rogowski, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Karl Wirtz . Four of the scientific assistants were already involved in the establishment of the institute; Bewilogua had been a PhD student with Debye in Leipzig and was in charge of setting up the refrigeration laboratory in Berlin; Ramm, whom Debye had also brought from Leipzig, and van der Grinten, whom he had brought from Liège, were involved in setting up the high-voltage laboratory; and Rogowski was responsible for setting up the spectroscopic department. Von Weizsäcker and Wirtz did not come to the institute until 1937.

Between 1936 and 1939, numerous visiting scholars from various countries worked at the institute. During this time, among others, Heinz Haber , Horst Korsching and Georg Menzer worked as doctoral students at the institute.

Debye, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1936, was considered a liberal director who gave his scientific staff a great deal of freedom in setting the priorities of their research work. The award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Carl von Ossietzky in 1935 prompted the National Socialists to campaign against the prize, which culminated in an Adolf Hitler decree in January 1937 in which Germans were banned from accepting the Nobel Prize. In the activity report of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society published in June 1937, the award of the Nobel Prize to Debye was nevertheless proudly highlighted, which was only possible because Debye had retained his Dutch citizenship. Debye later adhered to a confidential communication from the Reich Ministry of Education in October 1937, in which he was prohibited from submitting proposals for candidates who were officially entitled to him as a prize winner, and did not submit any proposals to the Nobel Prize Committee.

During his time as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, Peter Debye worked on three subject areas of physics: on the dielectric properties and "quasi-crystalline structures" of liquids, on the theory of the isotope separation process developed by Klaus Clusius and Gerhard Dickel in 1938 , and on low-temperature physics .

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in World War II

Confiscation by the Army Weapons Office

In December 1938 Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann , who worked at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, succeeded in nuclear fission of uranium , which opened up previously undreamt-of possibilities for generating energy. Physicists around the world also recognized the possibilities for military use of this technology in the form of the atom bomb. In April 1939, the Göttingen scientists Georg Joos and Wilhelm Hanle informed the Reich Ministry of Education about possible areas of application for uranium fission; it then called a meeting of experts in Berlin on April 29, 1939, attended by Walther Bothe , Gerhard Hoffmann and Peter Debye, among others . It was decided to set up a uranium project to research nuclear energy production; Hanle, Joos and their Göttingen colleague Reinhold Mannkopff were entrusted with the research.

The outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939 increased interest in the development of an atomic bomb. The Heereswaffenamt therefore decided to monitor the project, which was classified as extremely urgent, more intensively. In order to clearly answer the question of the technical feasibility of energy generation through nuclear fission and its possibilities for military use, a secret uranium project based at the Army Weapons Office was to be initiated, which is why the Göttingen scientists were withdrawn from their research assignment by the Army Weapons Office in August Moved into military exercises in 1939.

Kurt Diebner , the head of the Army Weapons Office, wanted to concentrate the project in one place. The scientists who came together for a working meeting prevailed with their suggestion that the project should be located at several different institutes. In addition to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, the Berlin Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, the Gottow Army Research Center , the Institute for Physical Chemistry at the University of Hamburg under the direction of Paul Harteck , the Department for Physics at the Heidelberg Kaiser Wilhelm Institute Institute for Medical Research under the direction of Walther Bothe , the Vienna Institute for Radium Research under the direction of Georg Stetter and the Physical Institute of the University of Leipzig with Werner Heisenberg and Robert Döpel included. The overall management of the project was with Kurt Diebner, who designated the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics as the central seat of the project.

Peter Debye was given leave of absence at the request of the Ministry of Education and the Army Weapons Office. When he refused to take on German citizenship, he was banned from instituting. He then decided to accept an invitation from Cornell University in Ithaca for a six-month visiting professorship. He left Europe by ship in mid-January 1940 and used the official stay in the USA, which was initially only planned for a limited period, to settle there permanently with his family. He took on the US citizenship in 1940. Finally, in mid-1941, he got a permanent position in the chemistry department at Cornell University. Until almost the end of the war, he was only listed as "on leave" in the personnel files of the Berlin University as well as at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Since he was officially able to leave Germany due to his Dutch citizenship, he is not considered to have emigrated before the National Socialists.

After Debye's departure, most of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was confiscated and, on January 1, 1940, placed under the formal management of the Army Weapons Office. Diebner, who set up his own office in the institute, took over the management of the Heereswaffenamt together with the Oberregierungsrat Walter Basche, the management of the rest of the institute, which was left with the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, was transferred to Debye's former assistant Ludwig Bewilogua transfer. Horst Korsching, Carl-Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Karl Wirtz were assigned to the uranium project by Debye's former employees, and the working group was soon reinforced by Fritz Bopp , Paul Müller and Karl-Heinz Höcker . Max von Laue and Hermann Schüler including their assistants were assigned to the department that remained with the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and were able to continue working on their original research topics.

In total, a little over 100 scientists worked on the uranium project in the participating institutes. While the nuclear research of the western allied countries primarily focused on the military application possibilities, the German researchers initially focused on the fundamental question of the manufacture of a reactor and the possibilities of procuring the uranium required for it. Heisenberg, who made important advances in the theory of reactor design in Leipzig, was already involved in the reactor tests at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics as a theoretical advisor from 1940, and from 1941 he took over their full theoretical support and evaluation. Finally, in 1941, together with Otto Hahn from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, he was appointed overall scientific director of the project.

The institute under Werner Heisenberg

Since it was no longer believed that nuclear technology could be used for military purposes in the short term, the Army Weapons Office was asked by the highest level in May 1942 to hand over the uranium project. The Kaiser Wilhelm Society saw this as an opportunity to get their physics institute back and at the same time continue to be involved in the project. The employees of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, together with Otto Hahn and Adolf Butenandt, campaigned for Werner Heisenberg to be appointed as the new director of the institute, who was ultimately able to prevail over Walter Bothe as another applicant. The administrative management of the uranium project was transferred to the Reich Research Council, which at the same time was withdrawn from the Ministry of Education and placed directly under the Reich Marshal Hermann Göring. This in turn appointed Abraham Esau , the president of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt, as his authorized representative for the uranium project.

Although the uranium project was the research project with the highest priority at the institute, Heisenberg endeavored from the beginning to expand the institute's scientific program to include new subject areas in physics and to network the institute with other institutes in various fields. For example, he conducted a biological-physical colloquium on questions of radiation biology and the physics of protein substances , to which, in addition to himself and his colleagues Wirtz and von Weizsäcker, Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for physical and electrochemistry and Nikolai Timofeeff-Ressovskyn from Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research gave lectures at the institute. With a further, multi-semester colloquium on cosmic radiation , he brought his previous focus topic closer to the scientists at the institute, as he intended to continue his research on this topic later in Berlin. The lectures were later published in a book that was valid for many years and was also translated into English after the war. Only part of the research on the use of nuclear energy was kept secret; overall there was great scientific interest in research on this topic. Heisenberg therefore held a series of lectures at the Technical University of Berlin on the possible applications of this technology in physics, chemistry and medicine, which also resulted in a book.

Overall, the scientific work at the institute was made increasingly difficult by the effects of the Second World War. In order to be able to manufacture an energy-generating reactor, large-scale experiments had to be carried out. A separate bunker laboratory was built for these on the premises of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Heisenberg succeeded in establishing a close collaboration with his previous competitor Walter Bothe, who was working on the production of a cyclotron in Heidelberg , so that he temporarily left some of his scientific staff, including Ewald Fünfer, to him.

From the summer of 1943, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics was gradually relocated to Hechingen in Baden-Württemberg , as the location in the capital of Berlin had become too dangerous due to bombing. The reactor was housed in a rock cellar under the Haigerloch Castle Church, where, in addition to the employees from the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics around Werner Heisenberg, scientists from Bothe's Heidelberg Institute tried to make it work. However, the end of the war ultimately prevented the imminent success.

The institute after the end of the war

At the end of April 1945 in Hechingen and Urfeld, six employees of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, Erich Bagge, Horst Korsching, Max von Laue, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Karl Wirtz, were captured by members of the ALSOS mission and, together with Kurt Diebner, Otto Hahn, Paul Harteck and Walther Gerlach, who were also involved in the German uranium project, were interned for six months at the English country estate of Farm Hall as part of Operation Epsilon . The conversations between the scientists were listened to in full and recorded in order to gain knowledge about the status of German nuclear research, in particular about its military use.

The troops of the ALSOS mission dismantled the test facilities in Haigerloch and confiscated a number of research reports. The remaining staff and the rest of the equipment were left to the advancing French army.

The institute building in Berlin-Dahlem survived the Second World War largely unscathed. The equipment and instruments that remained there, in particular the refrigeration laboratory, were dismantled by the Red Army after the end of the war and transferred to the Soviet Union. Some employees, including Ludwig Bewilogua, were taken to the Soviet Union as prisoners.

After the war, the institute was initially continued in Hechingen under very limited conditions. After the scientists interned in Farm Hall returned in early 1946, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics was rebuilt in the buildings of the former aerodynamic research institute in Göttingen under the direction of Werner Heisenberg and Max von Laue . Some apparatus from the research institute served as basic equipment.

Since Act No. 25 of the Allied Control Council , which regulated scientific research in post-war Germany, prohibited all investigations that served military purposes and, moreover, generally prohibited research in the field of applied nuclear physics, the work started as part of the uranium project could not be continued become. The law remained in force in West Germany until the Paris Treaties of May 1955. Heisenberg therefore had to define new focus areas for the institute. He established an experimental department headed by Karl Wirtz, which worked on the relatively new field of elementary particle physics , as well as a theoretical department in Theoretical Physics under Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, which was dedicated to the physical fundamentals of star evolution and the related issues of gas dynamics. Max von Laue continued to hold the position of Deputy Director and Bagge and Korsching continued to work as scientific assistants at the institute after their return from England. In 1947 a separate astrophysics department was founded at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, and Ludwig Biermann was appointed to head it.

In February 1948, the Max Planck Society was founded in Göttingen as the successor organization to the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, to which the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes, which were located in the British and American occupation zones, were affiliated. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics was continued as the Max Planck Institute for Physics from this point on.

In 1955 the institute was relocated to Munich at the request of Werner Heisenberg. Since Heisenberg decided to no longer deal with nuclear physics, even after nuclear physics research was permitted again in 1955, the institute was renamed the "Max Planck Institute for Physics and Astrophysics". In 1960 the institute became the independent Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics . In 1991 the Max Planck Institute for Physics and Astrophysics was split into the Max Planck Institute for Physics , the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics and the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics .

The former main building of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics on Boltzmannstrasse in Berlin-Dahlem was rented to the Free University of Berlin after the war , which initially housed the Institute for Physics there. It was later used by the Department of Economics. The "Tower of Lightning" was used by the archive of the Max Planck Society from 1999 . The archive of the Free University is now located in the former bunker laboratory. Part of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science has been housed in the institute's former director's villa since 2009.

literature

- Horst Kant : Albert Einstein, Max von Laue, Peter Debye and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin (1917–1939). In: Bernhard vom Brocke , Hubert Laitko : The Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Society and its institutes - The Harnack principle. De Gruyter-Verlag, 1996, pp. 227-244.

- Helmut Rechenberg : Werner Heisenberg and the research program of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (1940–1948). In: Bernhard vom Brocke, Hubert Laitko: The Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Society and its institutes - The Harnack principle. De Gruyter-Verlag, 1996, pp. 245-262

- Horst Kant: Berlin - Munich - The Max Planck Institute for Physics. In: Peter Gruss , Reinhard Rürup , Susanne Kiewitz (eds.): Places of thought - Max Planck Society and Kaiser Wilhelm Society - Breaks and Continuities, 1911–2011. Sandstein-Verlag, Dresden 2011 pp. 318–323 online .

- Mark Walker : An armory? Nuclear weapons and reactor research at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics , research program History of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society under National Socialism, Series Results, Issue 26, Berlin 2005 online, PDF

- Kristie Macrakis: Research funding from the Rockefeller Foundation in the “Third Reich”. The decision to support the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics financially, 1934–39 , in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft , 12th year, no. 3, Sciences in National Socialism (1986), pp. 348–379

- Werner Heisenberg: Max Planck Institute for Physics and Astrophysics in Munich. In: Yearbook of the Max Planck Society 1961, Volume II, Munich 1961, pp. 632–643 (self-presentation of the history of the institute, including KWI)

- Eckart Henning , Marion Kazemi : Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Institute for Physics (and Astrophysics) , in: Handbook on the history of the institute of the Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science 1911–2011 - data and sources , Berlin 2016, 2 volumes, volume 2: Institutes and research centers M – Z ( online, PDF 75 MB ), pp. 1177–1216.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Horst Kant: Albert Einstein, Max von Laue, Peter Debye and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin (1917-1939). In: Bernhard vom Brocke , Hubert Laitko : The Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Society and its institutes - The Harnack principle. De Gruyter-Verlag, 1996, pp. 227-244

- ↑ see Marion Kazemi , Eckart Henning : Chronicle of the Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science. 1911–2011 (= 100 years of the Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science. Part I). Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-428-13623-0 , page 81

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Helmut Rechenberg: Werner Heisenberg and the research program of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (1940-1948). In: Bernhard vom Brocke, Hubert Laitko: The Kaiser Wilhelm / Max Planck Society and its institutes - The Harnack principle. De Gruyter-Verlag, 1996, pp. 245-262

- ↑ Werner Heisenberg (Ed.): Lectures on cosmic radiation. Berlin 1943. (with contributions from the institute members E. Bagge, Fritz Bopp, Werner Heisenberg, G. Moltere, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Karl Wirtz as well as S. Flügge, A. Klemm and H. Volz (Berlin) and J. Meixner (Aachen )).

- ↑ Werner Heisenberg: The physics of atomic nuclei. Braunschweig 1943

- ↑ a b c d Horst Kant: Berlin - Munich - The Max Planck Institute for Physics. In: Peter Gruss, Reinhard Rürup, Susanne Kiewitz (eds.): Places of thought - Max Planck Society and Kaiser Wilhelm Society - Breaks and Continuities, 1911 - 2011. Sandstein-Verlag and Max Planck Society, Dresden 2011 p 318-323

- ↑ 1948: Foundation of the Max Planck Society. on the homepage of the Max Planck Society, accessed on June 26, 2016

- ↑ Timeline for the history of the institute on the homepage of the Max Planck Institute for Physics, accessed on October 1, 2017