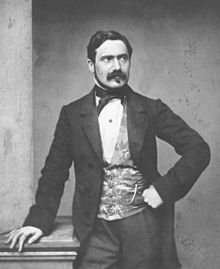

Max von Pettenkofer

Max Josef Pettenkofer , von Pettenkofer since 1883 (born December 3, 1818 in Lichtenheim near Neuburg an der Donau , † February 10, 1901 in Munich ), was a Bavarian chemist . He founded the hygiene institute named after him posthumously and is considered to be the first hygienist in Germany.

Life

Pettenkofer was born on the Einödhof Lichtenheim near Lichtenau on the northern edge of the old Bavarian Donaumoos as the fifth of eight children of the farmer Johann Baptist Pettenkofer (1786–1844) and his wife Barbara Pettenkofer (1786–1837). The family conditions were very poor. To attend school he was given to Munich in the care of his uncle Franz Xaver Pettenkofer , who was a royal Bavarian court and personal pharmacist. In 1837 Max Pettenkofer passed the final examination at Munich's old grammar school . He began studying natural science, pharmacy and, from 1841, medicine and chemistry at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . It was also his uncle who started an apprenticeship as a pharmacist from 1839 onwards. He then continued studying in 1841 and graduated there in 1843 with the doctorate to the doctor of medicine, surgery and obstetrics from. At the same time he acquired the license to practice as a pharmacist . Its first publication came out in 1842. In it he described a method for the detection of arsenic and for the separation of arsenic and antimony. He then worked on chemistry at the Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg and then moved to the Hessian Ludwig University in the laboratory of Justus von Liebig .

In June 1845 he married his cousin Helene (1819-1890). The marriage resulted in five children, three of whom died prematurely. Maximilian Pettenkofer (1853–1881) and their daughter Anna married developed independently. Riediger (1838-1882).

Since Max Pettenkofer could not find a job after graduating in Giessen, he returned to Munich and initially devoted himself to poetry. The result was the "Chemical Sonnets", which appeared in print in 1890. In 1845 he took a job at the Bavarian Main Mint . Here he dealt with processes for the refined extraction of gold, silver and platinum in the coinage of the Kronentaler . In 1847 he was appointed associate professor for pathological-chemical investigations at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich (LMU). His lectures from this time were titled “Dietetic-Physiological Chemistry” and “Public Health Care”. Important inventions from this time were his proposals for an improved method for the production of cement in 1849 . A year earlier he had invented the copper amalgam tooth filling. When his uncle died in 1850, he also took over the management of the court pharmacy. Here “Liebig's meat extract” was successfully produced and sold. In 1852 he was able to persuade Maximilian II Joseph (Bavaria) to call Justus von Liebig to Munich. In the same year Pettenkofer became full professor . In 1862 he took part in a very successful company. It imported meat extract from Uruguay under the name "Liebigs Extract of Meat Companie" with its headquarters in London. In the years 1864/65 he held the office of Rector of the University of Munich. In the same year he became the first German professor for hygiene and the first professor of this subject in Munich ; from 1876 to 1879 the first hygiene institute was built.

Max Pettenkofer presented Ludwig II. (Bavaria) to a private audience in 1865 with his ideas for keeping people healthy and urban hygiene. Ludwig then brought about a ministerial resolution, with which the scientific subject "Hygiene" was appointed on September 16, 1865 as a nominal subject. In the following years he fought for the hygienic renovation of the city of Munich. By 1883 he achieved that an exemplary drinking water supply and an efficient sewage system ( alluvial sewerage ) were set up, which brought significantly improved living conditions in the city. In 1882, King of Bavaria raised Max Pettenkofer to hereditary nobility .

From 1890 to 1899 he was President of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences . End 1893 emeritus , he gave in 1896 to his work at the court pharmacy. Towards the end of his life, however, he was increasingly sidelined because he did not want to recognize Robert Koch's bacteriological findings in cholera research . Although he had already put forward the thesis in 1869 that cholera and typhus are caused by specific microorganisms and poor environmental conditions, he was unable to prove it. When Robert Koch (1843–1910) found the pathogen of cholera in Vibrio cholerae in 1892, Pettenkofer experimented on himself with a Vibrio culture without becoming too seriously ill. He wanted to prove that these bacteria alone are not enough to trigger the disease.

Plagued by increasing pain and severe depression, Max von Pettenkofer shot himself at the age of 82 in his court pharmacist's apartment in the Munich residence. The autopsy revealed chronic meningitis and cerebral sclerosis .

Burial site and estate

His grave is located in the Old Southern Cemetery in Munich (grave field 31 - row 1 - place 33/34) ( location ).

His estate is kept in the Bavarian State Library and is scientifically maintained.

Services

Pettenkofer's most recognized field of work was the science of hygiene, which he himself defined and filled with content. He established hygiene as an independent area of medicine and also recognized the related economic aspects. Therefore, he also approached administration and engineers and developed a health technology that was used, for example, in the renovation of Munich. Munich owes Pettenkofer its sewer system and a central drinking water supply. Towards the end of the 19th century, Munich was considered one of the cleanest cities in Europe.

At the beginning of his professional career, chemistry and physiology were the preferred areas of work. One of the most important achievements of Pettenkofer is the discovery of periodic properties in chemical elements (1850). He thus created an essential basis for the development of the periodic table of the elements (according to Mendeleev's own statements, the work had an influence on him). He went beyond the triad classification of Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner , which was already widespread at that time , and discovered regularities with periods 8 and 16 (in other groups of 5). Due to a lack of support from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences , he was unable to continue his research. At Justus von Liebig he developed the bile acid detection and worked at the Royal Main Mint , where he used improved methods of precious metal smelting and coin production (1848–1849). In 1844, Pettenkofer discovered creatinine , an important metabolic product in muscle tissue . In 1857 he described the production of luminous gas from wood ( wood gas ) for the cities of Basel and Munich (1851) and examined (around 1860 and later at the Hygiene Institute) together with the physiologist Carl Voit (1831–1908) metabolic balances . From this, the two researchers developed the theory of the structure of all living things from three organic compounds that are essential for nutrition: protein , fats and carbohydrates . To this day, ventilators are built according to the "Pettenkofer principle". The meat extract (“ soup cubes ” according to Liebig) developed by Justus von Liebig and Pettenkofer was produced on an industrial scale with South American beef.

With Carl Voit, the pathologist Ludwig Buhl and the botanist Ludwig Radlkofer , he published the journal for biology from 1865 . Pettenkofer accompanied them as editor for 18 years.

Later Pettenkofer devoted himself to epidemiology . In contrast to his earlier work, these investigations have only historical value. Pettenkofer did not believe that the cholera , which also broke out in Munich in 1854, was triggered by a pathogen alone, but rather attributed the main importance to the soil and groundwater quality ( investigations and observations on the spread of cholera , 1855). He held this view for decades, u. a. at scientific "cholera conferences" such as the one in Weimar in 1867, and he stuck to it even after Robert Koch's discovery of the pathogen in 1884. In connection with the famous dispute with Robert Koch over the cause of cholera, Pettenkofer even swallowed a culture of cholera bacteria on October 7, 1892 . He got away with mild diarrhea , possibly because he was still resistant to the pathogen due to his illness in July 1854 . Pettenkofer took the view that the environmental conditions are of much more importance for the development of a disease than the mere presence of pathogens. He and some of his students who repeated the experiment did not get sick or only slightly, which confirmed Pettenkofer. However, he was wrong to the extent that he assumed a certain " contagious element Y" ( miasm ), which - like a chemical reaction - made the development of a disease possible in the first place. The site inspection that is common in epidemiology today and extensive statistical recording and evaluation of the epidemic was introduced by Pettenkofer and his students.

With regard to epidemic hygiene measures, Pettenkofer spoke out against the senseless restriction of public life in the event that the epidemic had already reached nationwide proportions. "Free movement is such a great good that we couldn't do without it, not even at the price that we were spared cholera and many other diseases."

Pettenkofer worked strictly scientifically and experimentally and is considered the founder of experimental hygiene ("conditional hygiene "). His investigations into clothing , heating , ventilation , sewerage and water supply were also experimental. Like his teacher v. Liebig Pettenkofer was a positivist , that is, he only recognized visible facts , for example, obtained in experiments , as a source of knowledge.

Pettenkofer made a mistake that continues to have an effect today, in that many people believe there is a " breathing wall ": he found early air change measurements in a room that after all the joints had supposedly been sealed, the air change rate decreased less than expected. From this he concluded that there was a significant exchange of air through the brick walls. Presumably he never thought of sealing the chimney of a stove in the room. According to Pettenkofer, the exchange of air through the room walls makes a significant contribution to cleaning the room air .

Pettenkofer published a total of more than 20 monographs and 200 original articles in scientific and medical journals. His services as the founder of hygiene, pioneer of environmental medicine , experimental field researcher, chemist and nutritional physiologist were and are recognized worldwide. The medicinal chemistry also owes him useful detection methods for arsenic ( Marsh test ), sugar and urine contents. For his scientific achievements, he was accepted on January 24, 1900 in the Prussian order Pour le Mérite for science and the arts.

The traditional hygienic indoor air value for CO 2 is named after Pettenkofer - the Pettenkofer number. Pettenkofer gave their limit value as 0.10%.

Memberships and honors

- Bavarian Academy of Sciences , extraordinary member (1846), full member (1856), president (1890–1899)

- Member of the Leopoldina (1859)

- External member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences (1874)

- Honorary Member ( Honorary Fellow ) of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1895)

- Foreign member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences (1898)

- Bavarian hereditary nobility (1883); Title excellence (1896); Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown (1900)

- Bunsen-Pettenkofer Honor Roll of the DVGW (1900)

- Honorary Citizen of the City of Munich (1872); Golden Citizen Medal of the City of Munich (1893); Gold Medal of the City of Munich (1899)

- Member of the Senior Medical Committee (1849)

- Member of the Munich Casual Society (1852)

- Harben Medal from the Royal Institute of Public Health , England (1897); Gold Medal of the Chemical Society

Names after Pettenkofer

- On the occasion of his 150th birthday, the Federal Republic of Germany issued a 5 D-Mark commemorative coin .

- The Max von Pettenkofer Institute (Institute for Hygiene and Medical Microbiology of the University of Munich ) at the Munich University is named after Max von Pettenkofer .

- In Munich Ludwigsvorstadt is Pettenkoferstraße named after him.

- One type of bacteria is named after Pettenkofer: Staphylococcus pettenkoferi .

- In Berlin-Friedrichshain a primary school and a street is named after Pettenkofer.

- The Bunsen-Pettenkofer Honor Roll of the German Gas and Water Association is named after him and Robert Bunsen .

- The "Pettenkofer process" , a painting restoration technique and a regeneration process for varnish that has gone blind .

- The Pettenkofer School of Public Health (PSPH) is named after Max von Pettenkofer . The PSPH LMU is supported by the Medical Faculty of the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich as well as by the two cooperation partners, the Helmholtz Center Munich and the State Office for Health and Food Safety.

Fonts

- Safe and easy way to clearly distinguish the arsenic from all other similar phenomena. In: Repert. for pharmacy. 77, 1842, p. 289.

- About Mikania Guaco. Dr. C. Wolfsche Buchdruckerei, Munich 1844, OCLC 311961721 (Dissertation University of Munich: Inaugural treatise by Max Pettenkofer, doctor of medicine, surgery and obstetrics and licensed pharmacist. 1844, 38 pages digitized from the Bavarian Library, call number Diss 2126/3 (2012 ), free of charge, 42 pages in the MDZ reader, no full text available, PDF on request).

- On the occurrence of a large amount of hippuric acid in human urine. In: Annals of Chemistry and Pharmacy . 52, 1844, pp. 86-90.

- Note of a new reaction to bile and sugar. In: Annals of Chemistry and Pharmacy. 52, 1844, pp. 90-96.

- About the refining of gold and about the widespread use of platinum. In: Munich. learned scoreboard. 24, 1847, pp. 589-598.

- About chemistry in its relation to physiology and patology. 1848.

- About the regular intervals between the equivalent numbers of the so-called simple radicals. In: Munich. Scholarly Scoreboard. 30, 1850, pp. 261-272, Ann. d. Chemistry and Pharmacy. 105, 1858, p. 187.

- About the difference between air heating and stove heating in their development on the composition of the air in the heated rooms. In: Polytechn. Journal. 119, 1851, pp. 40-51, 282-290.

- Studies and observations on the way in which cholera spreads. Munich 1855.

- About the most important principles of the preparation and use of the wood fluorescent gas. In: Journal for practical chemistry . 71, 1857, pp. 385-393.

- About the air exchange in residential buildings . Munich 1858. (online)

- About the haematonin of the ancients and about aventurine glass. In: Repert for Pharmacy. 73, 1857, pp. 50-53.

- About the air exchange in residential buildings. 1858.

- Reports on ventilation equipment. In: Treatises of the scientific-technical commission at the royal Bavarian academy. 2, 1858, pp. 19-68 and 69-126.

- About the determination of the free carbon dioxide in drinking water. In: J. f. practical chemistry. 82, 1861, pp. 32-40.

- About a method to determine the carbon dioxide in the atmospheric air. In: Journal for Practical Chemistry. 85, 1862, pp. 165-184. (babel.hathitrust.org)

- About respiration. In: Annals of Chemistry and Pharmacy. Suppl. 2, 1862/1863, pp. 1-52.

- About the function of clothes. In: Journal of Biology. Issue 1, 1865, pp. 180-194.

- Investigation of the substance consumption of normal people. In: Journal of Biology. No. 2, 1866, pp. 459-573.

- About the consumption of substances in sugar urine. In: Z. f. Biol. 3, 1867, pp. 380-444.

- Soil and groundwater in their relationship to cholera and typhus . Munich 1869.

- Relationship between air and clothing, home and soil: three popular lectures held at the Albert-Verein in Dresden on March 21, 23 and 25, 1872 . 1872. (full text)

- About food in general and about the value of meat extract as a component of human food in particular. In: Ann. d. Chemistry and Pharmacy. 167, 1873, pp. 271-292.

- Lectures on canalisation and drainage . Munich 1876.

- The soil and its connection with human health. In: Dtsch. Rundschau. 29, 1881, pp. 217-234.

- The Hygienic Institute of the Königl. bayer. Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich. 1882. (online)

- Handbook of Hygiene and Industrial Diseases. ( Second part (online) ), 1882.

- Lighting of the royal residence theater in Munich with gas and electric light. In: Arch. F. Hygiene. 1, 1883, pp. 384-388.

- Etiology of abdominal typhoid. In: Public Health Archives. 9, 1884, pp. 92-100.

- The cholera. 1884.

- Munich, a healthy city. 1889

- The pollution of the Isar by the flood system of Munich . Munich 1890.

- About the self-cleaning of the rivers. In: German medical weekly. 17, 1891, pp. 1277-1281.

- Cholera explosions and drinking water. In: Munich medical weekly. 48, 1894, pp. 22-223 and 248-251.

literature

- Otto Neustätter: Max Pettenkofer (= Master of Medicine . Volume 7 ). Julius Springer, Vienna 1925, DNB 361948220 .

- Edgar E. Hume: Max von Pettenkofer . New York 1927.

- Karl Kißkalt : Max von Pettenkofer (= great natural scientist . Volume 4 ). Scientific publishing company, Stuttgart 1948, DNB 452425700 .

- Alfred Beyer : Max von Pettenkofer . People and Health, Berlin 1956, DNB 450438716 .

- Claude E. Dolman: Pettenkofer, Max Josef von . In: Charles Coulston Gillispie (Ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography . tape 10 : SG Navashin - W. Piso . Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1974, p. 556-563 .

- Harald Breyer: Max von Pettenkofer. Doctor in the run-up to the illness (= humanists indeed ). Hirzel, Leipzig 1985, DNB 850561493 .

- Karl Wieninger : Max von Pettenkofer . Hugendubel, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-88034-349-7 .

- Eberhard J. Wormer : Pettenkofer, Max Josef. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 20, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-428-00201-6 , pp. 271-273 ( digitized version ).

- Gregor Raschke: Max von Pettenkofer's cholera theory in the crossfire of criticism - The cholera discussion and its participants . Dissertation. Technical University of Munich, 2007, DNB 989042227 . online (PDF)

- Martin Weyer-von Schoultz: Max von Pettenkofer (1818-1901): The emergence of modern hygiene from empirical studies of the basis of human life . Peter Lang, 2005, ISBN 3-631-54119-8 .

- Nadine Yvonne Meyer: The hygiene institute of the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich under Max von Pettenkofer as an international training and research facility. Dissertation. LMU Munich 2016. online (PDF)

- Werner Köhler: Pettenkofer, Max von. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. Volume 3, De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-019703-7 , p. 1132

Web links

- Literature by and about Max von Pettenkofer in the catalog of the German National Library

-

Works by and about Max von Pettenkofer in the German Digital Library

- Max von Pettenkofer - Cholera in Munich ( Memento from May 14, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Article by / about Pettenkofer, Max Josef von in the Polytechnisches Journal

- Max von Pettenkofer of the Donaumoos largest son in the Karlskron community, accessed on March 20, 2018.

- Estate of Max von Pettenkofer (1818–1901) Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, accessed on March 20, 2018.

- Marko Rösseler: December 3rd, 1818 - Max von Pettenkofer's birthday at WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

- Video at ARD-Alpha, 16 min. (Online until May 11, 2022) Stories Great minds: Necessity makes inventive Max Josef von Pettenkofer (1818–1901 / surgeon and founder of modern hygiene), Dr. Hope Bridges Adams-Lehmann (1855–1916 / first practicing doctor in Munich) and Johann Nepomuk von Nussbaum (1829–1890 / Chirung) discuss on a stage in the old southern cemetery.

Footnotes

- ↑ a b c d Volker Klimpel : About the scientific relationships between Max von Pettenkofer and Rudolf Biedermann Günther. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 11, 1993, p. 333 f.

- ↑ a b c Dieter Wunderlich: Max von Pettenkofer. 2006.

- ↑ Werner Köhler : Pettenkofer, Max von. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1132.

- ^ Max Leitschuh: The matriculations of the upper classes of the Wilhelmsgymnasium in Munich. 4 volumes. Munich 1970–1976; Volume 4, p. 10.

- ↑ Peter Styra: The Berching family Pettenkofer. Oberpfäelzer Kulturbund, p. 4.oberpfaelzerkulturbund.de (PDF; 1.54 MB, accessed on March 20, 2018)

- ↑ In 1849 he was the first to precisely describe the process of making Portland cement . He specifically affirmed the importance of sintering. See Christoph Hackelsberger: Concrete: Philosopher's Stone ?: Thinking about a building material. Vieweg publisher, Braunschweig / Wiesbaden 1988, p. 62.

- ↑ Heinz Seeliger : 100 years chair for hygiene in Würzburg. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 6, 1988, pp. 129-139, here: p. 130.

- ↑ Pettenkofer, Max von (1818–1901) Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (short biography + list of links), accessed on March 20, 2018.

- ^ Lexicon of Researchers and Inventors. Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Reinbek 1997, ISBN 3-499-16516-3 , p. 348/349.

- ^ Entry in the OPACplus of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek , accessed on October 23, 2013.

- ↑ see his report from 1869: Das Kanal- or Siel-System in Munich

- ↑ Eric R. Scerri: The periodic table, its story and its significance. Oxford Univ. Press, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-530573-9 , pp. 50ff.

- ^ Otto Westphal , Theodor Wieland , Heinrich Huebschmann: life regulator. Of hormones, vitamins, ferments and other active ingredients. (= Frankfurt books. Research and life. Volume 1). Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1941, p. 39.

- ↑ Axel Stefek: The Weimar barrel system as a measure of urban hygiene. In: Axel Stefek (Ed.): Water under the city. Streams, canals, sewage treatment plants. Urban hygiene in Weimar from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Weimar 2012, DNB 1027249310 , pp. 75–123, here pp. 88–91.

- ↑ Volker Klimpel: About the scientific relationships between Max von Pettenkofer and Rudolf Biedermann Günther. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 11, 1993, p. 338.

- ^ Gregor Raschke: Max von Pettenkofer's cholera theory in the crossfire of criticism - The cholera discussion and its participants. (PDF; 1 MB). Dissertation. Institute for the History and Ethics of Medicine at the Technical University of Munich - Klinikum rechts der Isar, June 25, 2007, accessed on March 20, 2018.

- ^ Max von Pettenkofer: What can be done against cholera. Munich 1873, p. 6 Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, accessed on June 25, 2020.

- ↑ JE Herberger, FL Winckler (Red.): Yearbook for practical pharmacy and related subjects. Palatinate Society for Pharmacy and Technology. Verlag Baur, Landau 1843, p. 193. (books.google.de)

- ↑ The Orden pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts. The members of the order. Volume II: 1882-1952. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-7861-1125-1 , p. 158.

- ↑ Holger Krahnke: The members of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen 1751-2001 (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, Volume 246 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Mathematical-Physical Class. Series 3rd volume 50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-82516-1 , p. 188.

- ^ Fellows Directory. Biographical Index: Former RSE Fellows 1783–2002. (PDF file) Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ One hundred and fifty years of the casual society of Munich 1837–1987. University printing and publishing house Dr. C. Wolf and Son, Munich 1987, OCLC 165901936 .

- ^ Max von Pettenkofer Institute

- ^ Pettenkofer's method. In: The large art dictionary by PW Hartmann .

- ↑ Mikania Guaco , contains among other things the bitter substance " guacin ", In: Lexicon of medicinal plants and drugs. Spectrum , Heidelberg.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Ignaz von Döllinger |

President of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences from 1890 to 1899 |

Karl Alfred Ritter von Zittel |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Pettenkofer, Max von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Pettenkofer, Max Josef von |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German chemist and hygienist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 3, 1818 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lichtenheim near Neuburg on the Danube |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 10, 1901 |

| Place of death | Munich |