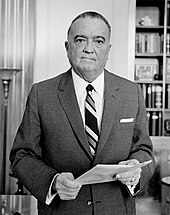

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover , known as J. Edgar Hoover and as Edgar Hoover , (born January 1, 1895 in Washington, DC ; † May 2, 1972 ibid) was the sixth director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) from May 10, 1924 and from March 23, 1935 until his death, the first director of the now renamed Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Life

Hoover was the youngest of four children of Dickerson Naylor Hoover (1856-1921) and Anna Marie Scheitlin (1860-1938). Both his father and grandfather worked in the state bureaucracy. His brother Dickerson N. Hoover Jr., who was 15 years older, also pursued a career in the civil service with police functions ; he was 1926 Supervising General Inspector of the Steamboat Inspection Service ("Inspector General of the Steamship Authority"). Hoover's eldest sister Lillian was born in 1882; after her marriage she was called Robinette. The second sister, Sadie Marguerite Hoover, died of diphtheria before Hoover was born in 1893 at the age of three .

Hoover grew up in Washington, DC and the neighborhood was dominated by civil servants. His parents were conservative and Christian religious, the mother was the dominant person in the household. Hoover spoke little of his life about his father, who suffered from severe depression and was therefore often admitted to psychiatric hospitals. In contrast, he had a close relationship with his mother, with whom he lived until her death in 1938.

In elementary school , Hoover was seen as a "mother's boy". But he prevailed at Central High School , where he was involved in the debating club and as captain of the Cadet Corps and achieved an above-average degree, but without significantly gaining self-confidence .

Hoover remained unmarried; he only entered into romantic relationships with a few women, including Lela Rogers, mother of film star Ginger Rogers , and actress Dorothy Lamour . Helen Gandy was his personal assistant from 1918 until his death .

His close relationship with deputy Clyde Tolson sparked rumors that Hoover was homosexual , but these remained unconfirmed. Hoover bequeathed most of his fortune to Tolson. In public, Hoover held puritanical views on sex.

Career

Hoover initially wanted to be a Presbyterian pastor, but then studied law at George Washington University ; he financed his studies with a job at the Library of Congress .

1917 to 1924: early career

After graduating, J. Edgar Hoover began working for the US Department of Justice in 1917 . In connection with the Russian Revolution of 1917, he soon became head of the section for the registration of enemy foreigners . In 1919 he became head of the newly established General Intelligence Division under Alexander Mitchell Palmer , in which he quickly acquired the reputation of an anti-communist by promoting the policy of the “hard hand”, including the deportation of Emma Goldmans and Alexander Berkmans , which he ordered . Along with Palmer organized Hoover at the height of the Red anxiety ( Red Scare ) in January 1920, the largest mass arrest in US history, the Palmer Raids , where about 10,000 suspected members and sympathizers of the Communist Party of the United States were imprisoned. The broad US public, to whom the suspects were presented in so-called perp walks , initially assessed these arrests positively.

In 1921, Hoover moved to the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) as Assistant Director ("Vice Director" ).

Mid-twenties to mid-thirties: building the FBI

In 1924 the BOI had a bad reputation and only around 650 employees who were not an effective federal police force. Under United States Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty , Director William John Burns had willingly used agents of the BOI to hinder the investigation of Daugherty and his fellow party members into a corruption affair, to intimidate journalists and to prepare the planned blackmail of a senator. When this was revealed, the Daugherty Burns scandal caused the BOI to lose its reputation. The newly appointed Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone when Calvin Coolidge took office recognized this and dismissed Director Burns. On May 10, 1924, he put Hoover in his place, who held this position until his death in 1972. Hoover expanded the organization and its sphere of influence enormously during his long tenure.

Hoover's most important goal in the first few years was to professionalize the BOI. It had two thrusts: on the one hand, the staff should pursue a professional ethos of incorruptibility and meticulousness , on the other hand, the forensic methods used should be scientifically sound. To achieve the latter, Hoover introduced a centrally administered file for fingerprints in 1925 , created a forensic laboratory, and established a training academy.

He recognized the importance of the mass media early on , which he cleverly used for his goals through a mixture of coercive measures and arrests of well-known gangsters , which were staged in an effective manner . In the mid-1930s, he became something of a movie star in the United States. Hoover rarely drew broad media criticism; Probably the most spectacular case occurred in the spring of 1934 in the Little Bohemia hotel complex in Manitowish Waters , Wisconsin, when five high-profile gangsters were released from captivity by FBI agents and two agents and one civilian were killed. Hoover professionalized the public relations division of the Bureau, since the early 1930s, today sponsored External Affairs Division a range of gimmicks and promotional items of the " G-Men ", the chewing gum cards, FBI badges, radio broadcasts, to the television series The FBI was enough, which - with Hoover as a consultant - should bring it to 240 episodes within nine years.

In 1935 the Bureau of Investigation was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation .

The time around and during World War II: international expansion

Even before the USA entered the war, J. Edgar Hoover's work shifted to defending against possible "enemies of the state", including in particular many intellectual dissidents. For example, Hoover personally appointed the FBI agent responsible for monitoring Klaus Mann . From 1939, the FBI was responsible for domestic intelligence work.

Furthermore, Hoover expanded its international sphere of influence during the Second World War . In 1940 he founded the Special Intelligence Service , which carried out extensive espionage operations in Mexico and Latin America until its dissolution .

The enormous efforts in the search and prosecution of subversives and radicals resulted in a neglect of the FBI's investigative work. In particular, the mafia networks of the American Cosa Nostra and Kosher Nostra remained undisturbed for a long time. Hoover publicly denied the existence of such networks, internally hindered their prosecution and also asserted his extensive influence over presidents, attorneys general and members of Congress in this direction.

In 1946 he received the Medal for Merit , at that time the highest civilian honor in the USA.

Post-war years: fight against communism

With the onset of World War II, and especially the Cold War , the FBI went to great lengths to track down spies and extremists , especially communists , who were widely believed to be subverting American politics and society. Hoover worked closely with members of the House Un-American Activities Committee and the Senate's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations ( Joseph McCarthy ) . According to reports from the New York Times , in 1950 Hoover made a list of 12,000 people who were "disloyal" to the American state and pleaded for their internment . However, this was not done.

In 1956, Hoover institutionalized COINTELPRO, a program to persecute (alleged) communists.

Sixties: fight against the civil rights movement

With the rise of the civil rights movement , Hoover turned increasingly against its leader; he feared the rise of a "black messiah" and made no secret of his aversion to Martin Luther King .

After the assassination attempt on John F. Kennedy in November 1963, Hoover personally took over the investigation by the FBI.

Hoover's relationship with Kennedy's successor Lyndon B. Johnson was far more relaxed than it was with Kennedy. Despite the differences on some political issues (Johnson advocated equality for African Americans and, unlike Hoover, initially had a good relationship with Martin Luther King), both were said to have had a good relationship. When Hoover was threatened with forced retirement for reasons of age, President Johnson issued a special decree to exempt him from this regulation. This enabled Hoover to remain in office and continue to exercise it after 1969, when Richard Nixon took over the presidency, with whom he - unlike Johnson - had a more differentiated relationship.

death

J. Edgar Hoover died while sleeping of heart failure on May 2, 1972 in Washington, DC. As the first unelected civil servant and the 22nd person ever, he was honored to have his body laid out in the Capitol on the Lincoln catafalk , which was originally built for Abraham Lincoln's coffin . He was buried next to his eldest sister in his parents' family grave.

Posthumous effect

The FBI headquarters in Washington, DC is named after J. Edgar Hoover. Even decades after his death, however, Hoover divided public opinion, due to Hoover's illiberalism, for example, the Democratic Senator Howard Metzenbaum wanted to cancel the dedication of the FBI building in 1993. In 1980 Hoover's assessment had become so bad that serious observers stated that he had "created a blueprint [...] for American fascism".

evaluation

Hoover has polarized the public throughout his life and beyond. From 1935 at the latest, he enjoyed a high reputation in the USA that could hardly be damaged. In Middle America in particular , Hoover was traded as a "demigod".

Hoover's reputation deteriorated rapidly after his death; while in 1965 84% of the population rated Hoover as "highly beneficial", in 1975 that number had dropped to just 37%. Hoover gained a place in American pop culture as "the phone bugger, bedroom bugger, blackmailer, scandal dealer, racist, character killer, poisoner of the source of intellectual and political freedom." The Palmer Raids , in which Hoover played a central role for the first time, are now interpreted as the first step into a surveillance state.

Hoover's almost complete control of the FBI is attributed to his manipulative tactics; Hoover tied people to himself through small favors - for example, FBI agents took over the organization and cost of travel for US Congressmen - and leaked information to the press that was glorified by the FBI and himself.

Secret dossiers

It is known that Hoover had numerous people observed and wiretapped because they had different political or moral ideas than he did. Although his relations with numerous top politicians in the United States - such as the Kennedy brothers - were extremely bad, he managed to maintain his post as head of the FBI (or its predecessor agency) over the terms of eight US presidents ( Calvin Coolidge to Richard Nixon ) to keep. This is why Hoover has sometimes been called the most powerful man in the United States. Characteristic in this context - regardless of whether he actually uttered it - is the saying ascribed to Hoover: "I do not care who is President below me."

Hoover's most important instrument for maintaining power is considered to be extensive dossiers on countless public figures in the United States such as Frank Sinatra and Charlie Chaplin , but above all on high-ranking politicians from the two major parties. These dossiers, in which Hoover recorded especially morally piquant misconduct and criminal involvement of the persons concerned, he systematized with the help of an encrypted system of order that he had designed himself and that was based on special file numbers. These file numbers - peculiar numerical and letter codes - were composed in such a way that they only made sense to himself, but only seemed like cryptic “letter salad” to other people and were accordingly inscrutable for them. The purpose of this special encryption was to ensure that only he (and a few confidants) knew where in the FBI's archives, which comprised millions of files, the files on a particular person could be found.

Fonts (selection)

- Persons in Hiding (1938)

- Masters of Deceit (1958)

- A Study of Communism (1962)

- Crime in the United States (1963)

Movies

- In The X-Files: The FBI's Scary Cases (1994) Season 1 Episode 19 - Transformations : Founder of the X-Files. The first X-File was created in 1946 by J. Edgar Hoover personally.

- In The Untouchables , Washington Post Vice President Ben Bradlee (Jason Robards) says that as a young reporter he was told that a successor to J. Edgar Hoover was being sought. He believed and wrote it, whereupon President Johnson then made Hoover a life official at a press conference (despite his old age) and then mocked Bradlee. Bradlee brings this example to show what can happen when you report “the truth”. Chronologically it doesn't quite fit because it happened only a few years ago and not when he was a "young man".

- In the 1971 film Bananas , Dorothi Fox plays FBI man Hoover in a Woody Allen comedy .

- The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover ( I'm the boss - scandal at the FBI ), USA 1977, directed by Larry Cohen , with Broderick Crawford in the role of elder and James Wainwright in the role of the younger Hoover.

- In Oliver Stone's biopic Nixon (1995) about Richard Nixon's political work , Hoover was portrayed by Bob Hoskins .

- In The Rock (1996), the British spy John Patrick Mason (Sean Connery) stole a microfilm containing American government secrets while J. Edgar Hoover was still alive, but was caught on the Canadian border and spent years in jail without charge. At the end of the film, after a hint from Mason, the microfilms come into the hands of the main character Dr. Stanley Goodspeed (Nicolas Cage).

- In Michael Mann's Public Enemies (2009) , Hoover was played by Billy Crudup .

- In 2011, director Clint Eastwood filmed the life of J. Edgar Hoover with Leonardo DiCaprio in the lead role under the title J. Edgar .

- 2013 The Curse of Edgar Hoover by Marc Dugain with Brian Cox as John Edgar Hoover and Anthony Higgins as Clyde Tolson . The documentary fiction thematizes the FBI's involvement in US politics.

- In 2014, Hoover, played by Dylan Baker , made a few appearances in the film Selma , which is mainly about the black protest marches to gain the right to vote. His aversion to Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement is made particularly clear here.

- 2018 The Man in the High Castle (TV series) , from season 3 - played by William Forsythe , Hoover takes on the role of director of the American Reich Bureau of Investigation (fictional counterpart to the FBI) in the dystopian alternative world scenario.

literature

- William Beverly: On the Lam: Narratives of Flight in J. Edgar Hoover's America . University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, MS 2003, ISBN 1-57806-537-2 .

- William B. Breuer: J. Edgar Hoover and His G-Men . Praeger, Westport, CT 1995, ISBN 0-275-94990-7 .

- Douglas Charles: J. Edgar Hoover and the Anti-interventionists: FBI Political Surveillance and the Rise of the Domestic Security State, 1939-1945 . Ohio State University Press, Columbus, OH 2007, ISBN 978-0-8142-1061-1 .

- Marc Dugain : La malédiction d'Edgar . Gallimard, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-07-033967-X ( German : "Der Fluch des Edgar Hoover", Frankfurter Verlagsanstalt, Frankfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-627-00147-6 ).

- Curt Gentry: J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets . WW Norton, New York, NY 1991, ISBN 0-452-26904-0 .

- Richard Hack: Puppetmaster: The Secret Life Of Edgar Hoover . Phoenix Books, 2007, ISBN 1-59777-512-6 .

- Mike Forest Keen: Stalking the Sociological Imagination: J. Edgar Hoover's FBI Surveillance of American Sociology . Greenwood Press, Westport, CT 1997, ISBN 0-313-29813-0 .

- Richard G. Powers: Secrecy and Power: The Life of J. Edgar Hoover . Simon & Schuster, New York, NY 1987, ISBN 0-02-925060-9 ( German : "The power in the background: J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI", Kindler, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-463-40088-X ) .

- Anthony Summers: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover . GP Putnam, New York, NY 1993, ISBN 0-575-04236-2 ( German : "J. Edgar Hoover, Der Pate im FBI", Langen / Müller, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7844-2472-4 .).

- Athan Theoharis, John Stuart Cox: The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition . Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA 1988, ISBN 0-87722-532-X .

- Tim Weiner: FBI. The real story of a legendary organization . S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-10-091071-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about J. Edgar Hoover in the catalog of the German National Library

- Biography on Spartacus Educational (English)

supporting documents

- ^ A b c Curt Gentry: J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets . WW Norton, New York, NY 1991, pp. 62 f .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Maurer, David: J. Edgar Hoover: Fighting Crime, Threatening Presidents, and Intimidating Just About Everyone . In: Biography . tape 7 , no. 9 , 2003, p. 76-96 .

- ^ Arthur W. MacMahon: Selection and Tenure of Bureau Chiefs in the National Administration of the United States II . In: The American Political Science Review . tape 20 , no. 4 , 1926, pp. 770-811, p. 782 , JSTOR : 1945424 .

- ↑ Theoharis, Athan G., Tony G. Poveda, Susan Rosenfeld & Richard Gid Powers: The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide . Greenwood, Westport, CT 1998, pp. 332 .

- ^ Curt Gentry: J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets . WW Norton, New York, NY 1991, pp. 63 .

- ^ Curt Gentry: J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets . WW Norton, New York, NY 1991, pp. 65-67 .

- ↑ Bullough, Vern L .: Problems of Research on a Delicate Topic: A Personal View . In: The Journal of Sex Research . tape 21 , no. 4 , 1985, pp. 375-386, p. 383 , JSTOR : 3812371 .

- ^ Stanley Coben: J. Edgar Hoover . In: Journal of Social History . tape 34 , no. 3 , 2001, p. 703-706, p. 704 , JSTOR : 3789824 .

- ↑ a b Theoharis, Athan G. Tony G. Poveda, Susan Rosenfeld & Richard Gid Powers: The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide . Greenwood, Westport, CT 1998, pp. 334 .

- ↑ Bullough, Vern L .: Problems of Research on a Delicate Topic: A Personal View . In: The Journal of Sex Research . tape 21 , no. 4 , 1985, pp. 375-386, p. 382 , JSTOR : 3812371 .

- ^ Kurt A. Schmautz: Review of "J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets by Curt Gentry ” . In: Michigan Law Review . tape 90 , no. 6 , 1992, pp. 1812-1818, p. 1813 , JSTOR : 1289450 .

- ^ A b David Williams: The Bureau of Investigation and Its Critics, 1919–1921: The Origins of Federal Political Surveillance . In: The Journal of American History . tape 68 , no. 3 , 1981, p. 560-579, p. 561 , JSTOR : 1901939 .

- ↑ Perp Walk: The History Of Parading Criminal Suspects National Public Radio , July 7, 2011 (English)

- ↑ David Williams: The Bureau of Investigation and Its Critics, 1919-1921: The Origins of Federal Political Surveillance . In: The Journal of American History . tape 68 , no. 3 , 1981, p. 560-579, p. 562 , JSTOR : 1901939 .

- ^ A b History of the FBI: Lawless Years: 1921–1933. Federal Bureau of Investigation, archived from the original August 4, 2002 ; Retrieved March 11, 2008 .

- ^ A b c Curt Gentry: J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets . WW Norton, New York, NY 1991, pp. 124-127 .

- ^ A b David Cunningham: The Patterning of Repression: FBI Counterintelligence and the New Left . In: Social Forces . tape 82 , no. 1 , 2003, p. 209-240, p. 211 , JSTOR : 3598144 .

- ↑ Kenneth O'Reilly: The Roosevelt Administration and Black America: Federal Surveillance Policy and Civil Rights during the New Deal and World War II Years . In: Phylon . tape 48 , no. 1 , 1987, pp. 12-25, p. 14 , JSTOR : 274998 .

- ^ Claire Bond Potter: "I'll Go the Limit and Then Some": Gun Molls, Desire, and Danger in the 1930s . In: Feminist Studies . tape 21 , no. 1 , 1995, p. 41-66, p. 41 , JSTOR : 3178316 .

- ^ Richard Gid Powers: One G-Man's Family: Popular Entertainment Formulas and J. Edgar Hoover's FBI In: American Quarterly . tape 30 , no. 4 , 1978, p. 471-492, p. 471 , JSTOR : 2712296 .

- ↑ Andrea Weiss: Communism, Perversion, and Other Crimes Against the State: The FBI Files of Klaus and Erika Mann . In: GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies . tape 7 , no. 3 , 2001, p. 459-481, p. 474 .

- ^ W. Dirk Raat: US Intelligence Operations and Covert Action in Mexico, 1900-1947 . In: Journal of Contemporary History . tape 22 , no. 4 , 1987, pp. 615-638, p. 629 , JSTOR : 260813 .

- ↑ HSCA III, 460, Congressional Special Committee on the Assassination attempt on John F. Kennedy, Robert S. Blakey ; Victor Navasky , Kennedy Justice , Atheneum, 1971, pp. 44-45; Salerno / Thompkins, The Crime Confederation. Cosa Nostra and Allied Operation in Organized Crime, Doubleday, NY, 1969, pp. 306 f.

- ↑ Victor Navasky , Kennedy Justice , Atheneum, 1971, p. 168 (Hoover dismisses FBI report on mafia as "bullshit"). Victor Navasky , Kennedy Justice , Atheneum, 1971, pp. 44-45; Salerno / Thompkins, The Crime Confederation. Cosa Nostra and Allied Operation in Organized Crime, Doubleday, NY, 1969, pp. 306 f .; see also HSCA III 460 (Hoover publicly denies a spectacular Mafia raid by the New York FBI). Victor Navasky , Kennedy Justice , Atheneum, 1971, pp. 44-45 (Hoover rejects the recommendations of a federal special commission on organized crime and is successful in dissolving them).

- ↑ HSCA III, 460, Special Congressional Committee on the Assassination attempt on John F. Kennedy, Robert S. Blakey, Hoover's Influence on Presidents, Attorney General, and Congress

- ↑ John Stuart Cox, Athan G. Theoharis: The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition . Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA 1988, pp. 312 .

- ↑ David Cunningham: Understanding State Responses to Left- versus Right-Wing Threats: The FBI's Repression of the New Left and the Ku Klux Klan . In: Social Science History . tape 27 , no. 3 , 2003, p. 327-370, p. 361 f .

- ↑ The thickest question mark in the world , article from March 16, 1992 by Rudolf Augstein on Spiegel Online

- ↑ Johnson's hidden loyalities ( Memento from September 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The life and carreer of J. Edgar Hoover ( Memento of November 21, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Michael R. Belknap: Secrets of the Boss's Power: Two Views of J. Edgar Hoover . tape 14 , no. 4 , 1989, pp. 823-838, p. 823 , JSTOR : 828541 .

- ↑ David Johnston: Senator Wants Hoover's Name Off FBI Building . In: The New York Times . September 26, 1993, p. 1/32 ( query.nytimes.com ).

- ^ Frank J. Donner: The Age of Surveillance: The Aims and Methods of America's Political Intelligence System . Albert Knopf, New York, NY 1980, pp. 125 (English): “Hoover […] forged […], a blueprint for American fascism.”

- ↑ Neil J. Welch, David W. Marston: Inside Hoover's FBI: The Top Field Chief Reports . Doubleday, Garden City, NY 1984, ISBN 0-385-17264-8 , pp. 198 f .

- ^ Richard G. Powers: G-Men: Hoover's FBI in American Popular Culture . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, IL, pp. 225 (English): “the phone tapper, the bedroom bugger, the blackmailer; the scandal monger, the racist; the character assassin; the poisoner of the well of intellectual and political freedom. "

- ^ Gilbert Geis, Colin Goff: Lifting the cover from undercover operations: J. Edgar Hoover and some of the other criminologists . In: Crime, Law and Social Change . tape 18 , no. 1 , 1992, p. 91-102, p. 92 .

- ↑ J. Edgar Hoover's brutal empire of paranoia , article of March 13, 2012 by Jan Küveler on Welt Online

- ↑ "American Gestapo" , Interview by Holger Stark with Tim Weiner from March 12, 2012 on Spiegel Online

- ↑ X-Files S01E19 (minute 14:30)

- ↑ The Man in the High Castle (TV series). Amazon Prime Video, accessed February 15, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hoover, J. Edgar |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hoover, John Edgar (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Founder and Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 1, 1895 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Washington, DC , United States |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 2, 1972 |

| Place of death | Washington, DC , United States |