Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale [ˈnaɪtᵻnɡeɪl] (born May 12, 1820 in Florence , Grand Duchy of Tuscany ; † August 13, 1910 in London , England ) was a British nurse , statistician , founder of modern western nursing and influential reformer of sanitary and health care in Great Britain and British India . The mathematically talented Nightingale is also considered a pioneer in the visual illustration of relationships in statistics.

Nightingale was of the opinion that there should be independent nursing knowledge in addition to medical knowledge, and also represented this in her writings on nursing, which are considered the founding writings of nursing theory . Among other things, she dealt with the effects of the environment on health. Their training model, known as the Nightingale system , provided for the training of young professionals, primarily by experienced nurses.

During the Crimean War (1853-1856) she led a group of nurses who looked after wounded and sick British soldiers in the military hospital in Scutari, Turkey (today's Istanbul district of Üsküdar ). Since she visited the patients with a lamp in hand on her rounds at night, Nightingale entered British folklore as Lady with the Lamp .

In fact, Nightingale was only marginally involved in the direct care of the injured and sick. Your achievement in Scutari consisted in the creation and maintenance of a rudimentary hospital operation. Nightingale returned to Great Britain chronically ill after the Crimean War and from then on led a secluded life as an invalid. However, through her numerous publications and correspondence, she influenced several health reforms.

Meaning of Nightingale's work

For today's care

The 19th century is also known as the "century of medicine". As a result of the advances in diagnostics and therapy, the "infirmaries" turned into hospitals in the modern sense. People seeking healing began to go to hospitals specifically to receive treatment. Accordingly, trained nursing staff was needed - instead of nurses - who could support the doctors in the therapy and who were more comfortable with the patients.

While in other European countries, especially in France and Germany, Catholic orders made the training of carers their task, little happened in Great Britain. Very few monasteries and orders had survived the English Reformation. The British public became painfully aware of this through publications by Nightingale. The training of nursing staff was then seen as a national task for which donations were collected.

The Nightingale School of Nursing at St Thomas' Hospital in London, founded by Nightingale, became the nucleus of this professionalization. Hospitals in all British regions subsequently requested graduates who were to reform the care system at their own facility and introduce training. Through a kind of pyramid scheme, the Nightingale Nursing spread across the entire Commonwealth. The nursing profession in Anglo-Saxon countries is now more demanding in terms of training - e. Sometimes at university level - and assigns the nurse far more competencies than e.g. B. the health and nurse in Germany.

In contrast to this, the traces of the care of the order can still be seen with us today: Salutation as a “sister”, charity as an essential motivation, low remuneration and low public reputation can also be traced back to the religious origin. Nightingale was instrumental in making nursing a socially respected and recognized career path for women in Great Britain and the countries belonging to the Empire , and set educational standards that were first applied in the nursing school she founded.

For nursing science and statistics

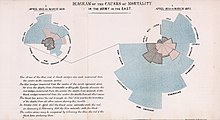

Nightingale is considered to be the inventor of the polar area diagram , a circle diagram with different radius lengths, which she mainly used to depict cyclical processes. She also propagated social science field experiments in her Notes on Nursing .

Much of her work consisted of information gathering and processing as a management task. So she developed questionnaires that were distributed in clinics in order to identify grievances and remedy them verifiably. She has used this scientific approach, using statistical analysis, not only in health care, but also in her efforts to improve living conditions in British India .

Nightingale is the first woman to be admitted to the British Royal Statistical Society ; later she also received honorary membership of the American Statistical Association .

Awards

For her achievements Nightingale was awarded the Royal Red Cross by Queen Victoria in 1883 and in 1907 was the first woman to be accepted into the Order of Merit by King Edward VII . Today, each on her birthday the International Day of Care (also Florence Nightingale Day, Eng. Origin International Nurses Day, IND ) committed, and the International Committee of the Red Cross lends since 1912 in memory of them, the Florence Nightingale Medal , which is considered to be the highest distinction that can be bestowed on caregivers.

International impact and reception

Nightingale's work in the Crimean War (1854-1856) inspired Henri Dunant , co-founder of the Red Cross , in view of the Battle of Solferino (1859).

Life

1820 to 1836: origin and early years

Nightingale's mother Fanny, b. Smith, came from a politically liberal family. The maternal grandfather, the merchant and politician William Smith, campaigned in the British House of Commons for the rights of the lower classes, the worldwide ban on slavery and freedom of religion .

The father was William Edward Nightingale , born in 1794 as William Edward Shore, who had inherited a sizable fortune from an uncle in 1815. According to the provisions of the will, he changed his last name from Shore to Nightingale. He was a school friend of Fanny Smith's younger brother Octavius and met his later wife, who was six years his senior, in 1811.

William Nightingale and Fanny Smith married in 1818 and toured Europe for two years immediately after they were married. Nightingale's older sister Parthenope was born in Naples in 1819 and named after the Greek name of her native city. Florence Nightingale's birthplace was the Villa Colombaia in Florence . As with the older daughter, the Nightingale couple chose a first name based on their place of birth. The family returned to Great Britain in the winter of 1820 and initially settled in Lea Hurst in Derbyshire . However, Fanny Nightingale found the winters there too severe and the opportunities to participate in social life too limited. In 1825, William Nightingale also acquired the Embley Park estate in Hampshire , which became the family's main residence.

Several letters to family members have survived from Nightingale's childhood who, in the opinion of the biographer Mark Bostridge, showed a great linguistic talent and observation at a very early age. By the age of nine, she spoke French so well that she was able to summarize a sermon for her mother in this language. From 1831 the Cambridge- educated father took over a large part of the upbringing of his daughters. He taught them Latin , Greek , German , French and Italian as well as mathematics, history and philosophy . The additionally committed tutor was responsible for teaching drawing and music .

Fanny and William Nightingale were followers of Unitarianism , a liberal and dogma-free Christian denomination, which, among other things, rejected the doctrine of the Trinity of God. Even if Bostridge emphasized Nightingale's faith, which became increasingly heterodox in the course of her life , individual elements of the Unitarian ethos were formative for her: the belief in social progress and in a moral obligation to society as well as the great importance attached to service to the community has been. Letters from the 1830s show that the Nightingale family organized and paid for medical care for the villagers near Lea Hurst during this period. Nightingale gained her first experience in nursing by caring for sick family members, but from a very young age accompanied her mother and her governess on visits to the sick in the surrounding villages. Diary entries by Nightingale, who was only ten years old, about the suicide of a young mother indicate that this gave her an early impression of the living conditions of the poor.

1837 to 1844: Decision for nursing

In January 1837 a flu epidemic struck the south of England. Nightingale was one of the few who stayed healthy and devoted four weeks to caring for the sick. In a letter to her sister, she stated that she acted as a “nurse, governess, assistant pastor and doctor”. During this time there was also a religious awakening experience that was so formative for her that the anniversaries remained a special event for her throughout her life. On February 7, 1837, Nightingale wrote in her diary: “God spoke to me and called me into his service.” The voice did not say what kind of service it was. Nor does she give any indication in her diary of the manner in which this call was expressed. However, there are indications in her notes and diaries that she (also) heard the call of God in later phases of life.

Nightingale's growing social engagement was interrupted by a year and a half family trip through France and Italy. The family returned to Britain on April 9, 1839, and in early May Florence Nightingale was introduced to the court of the young Queen Victoria . Thanks to a cousin who studied mathematics at Cambridge and was a guest at Lea Hurst for a few weeks, she began to deal more and more with mathematics from June 1839.

Her parents were skeptical of her new area of interest, and her mother in particular would have preferred if her daughter, in the eyes of contemporaries, had concentrated on activities that were more appropriate for a woman. However, thanks to the insistence of her aunt Mai Smith, the parents eventually gave in and hired a tutor for their studies. Letters from this time show that Nightingale found her life to be more and more banal. The family lived alternately at Lea Hurst and Embley Park, interrupted by extended visits to relatives or stays in London during the ball season. The mother's hope to receive members of the British aristocracy as house guests at Embley Park was not fulfilled. With the Nightingales, however, frequented a number of respected British politicians such as Charles Shaw-Lefevre and Lord Palmerston , who later became Prime Minister. Over the years, Embley Park has also hosted personalities such as Leopold von Ranke , Charles Darwin , the botanist William Jackson Hooker , Lord Byron's widow Anne Isabella Noel-Byron and her daughter Ada Lovelace .

The acquaintance of the Prussian ambassador Christian von Bunsen , who had suggested the establishment of hospitals in both Rome and London , had a long-lasting influence on Nightingale . Bunsen introduced them to the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Schleiermacher . Inspired by him, she dealt with David Friedrich Strauss ' sensational work Das Leben Jesu, critically edited . Bunsen himself had undertaken comparative religious studies, and his ideas also shaped Nightingale's work Suggestions for Thought , which appeared much later .

In the summer of 1844 Nightingale became certain that she would devote her life to nursing. Crucial for her decision was the meeting with the American doctor Samuel Gridley Howe and his wife Julia , who were guests at Embley Hall during their honeymoon. Howe had established the first school for the blind in the United States. Florence Nightingale asked him whether he thought it inappropriate for a young woman like her to devote herself to nursing in a similar way as these nuns of the nursing congregations do. Howe replied: “My dear Miss Florence, it would be unusual, and in England the unusual is usually felt to be inappropriate. But I would advise you to go this way if you feel called to do so. Act according to your inspiration and you will find out that there will be nothing inappropriate or unladylike about doing your duty for the benefit of others ... "

1845 to 1846: differences with parents

In the summer of 1845 Nightingale first discussed her plans with her family to become active in the nursing sector. After months earlier witnessing a sick person dying as a result of her carer's ineptitude, she had decided that she needed basic nursing training first. So she wanted to do a three-month internship in the Salisbury hospital and then buy a small house in which she would live together in a kind of Protestant sisterhood with women of similar origins and education and care for the sick. The proposal met with strict rejection in her family.

Those who fell ill in Britain in the mid-19th century were usually cared for at home. British hospitals were still charities at the beginning of the 19th century, caring for those in need free of charge if they had a letter of recommendation from one of the facility's supporters. People with tuberculosis , smallpox , or cancer were not admitted, and obstetrics were not given either . It was only in the course of industrialization and the associated urbanization of the population that hospitals in Great Britain gained in importance for general health care. The German Hospital in London, initiated by Christian von Bunsen and visited by Nightingale in June 1846, is therefore almost certainly the first hospital that she ever entered. Hospitals in the modern sense did not develop until after 1846, when the spread of modern anesthesia made other forms of interventions possible, but also required organized and careful all-day care of the patients treated.

The strict rejection of her wish by the family was based, alongside Nightingale's fragile health, on the poor reputation of the nursing profession. The nurses who worked in British hospitals in the first half of the 19th century were usually former servants or widows who could not find other employment and were therefore forced to make a living from this work. No better was the reputation of the nurses who cared for the sick in their homes. Charles Dickens caricatured such a nurse in his novel Martin Chuzzlewit , published from 1842 to 1843 in the character of Sairey Gamp, as incompetent, careless, addicted to alcohol and corrupt. The model of his character was the sister who temporarily looked after a sick servant in the household of his sponsor and friend Angela Burdett-Coutts .

Dickens' account was so apt to his readers that the colloquial term Gamp developed for the two-tone umbrella that Sairey Gamp habitually carries around with him . Indeed, many of the sisters did their ministry under the influence of alcohol, and it was common practice to give them alcoholic beverages or money for their purchases in gratitude for their services. The reputation that especially those sisters who worked during the night also fulfill the sexual wishes of their patients put the profession close to prostitution . However, it should not be overlooked that British society tended to resort to these means of discrediting quickly, especially when it came to the lower classes of society. In addition, the achievements of Nightingale Nursing were to be highlighted later through the degradation of the past.

Nightingale wasn't the only one looking to create a career for women with a nursing calling. As part of the Anglican Oxford Movement , two sororities had been founded, which were based on active congregations of the Catholic Church. Because of their proximity to the Roman Catholic Church , these sororities met with widespread rejection in the British public. Elizabeth Fry , best remembered as a prison reformer , founded the Institution of Nursing Sisters in 1840 . Her students came from the same class of the population that Dickens' fictional Sairey Gamp came from. However, they had to be able to read and write at least, wore uniforms and went through a three-month training course. Fry's sisters were primarily devoted to providing free health care for the poor and were funded by private nursing services in wealthier households and occasional hospital assignments. Fry died as early as 1845, and it is unlikely that Nightingale would ever meet her.

On January 18, 1846, Nightingale made another attempt to get her parents' permission to train in nursing. This time she wrote to her father in writing because she no longer felt able to address this issue directly to her parents without emotion. This time, too, she met with rejection.

As assured to her parents, she did not repeat her wish. She continued to read reports on hospitals and public health. In response to the prevailing economic crisis, a number of possible social reforms were discussed in the 1840s that would improve the living conditions of the lower strata of the British population. Nightingale followed these discussions with great interest since 1840, and it is very certain that, among other things, Edwin Chadwick's Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Laboring Class of Great Britain , which is considered a milestone in public health, was published shortly after its publication in 1842 read.

1846 to 1850: Failed marriage plans

Richard Monckton Milnes was now visiting the Nightingale family more often, and they were obviously considering Florence as a life partner. The philanthropist , man of letters and politician corresponded to the image Fanny Nightingale in particular had of a suitable son-in-law, and Florence valued Milnes' humor and commitment during the great famine in Ireland . Before deciding for or against Richard Milnes, she accompanied the Bracebridge couple, who were friends with their family, on a month-long trip to Rome. The couple gave Nightingale greater freedom than she was used to at home, which she used to visit various Roman hospitals.

Upon her return to the UK, Nightingale turned down Milnes' marriage proposal. The details of the conversation between Milnes and Nightingale are not known. It is possible that she by no means clearly rejected the application, but was misunderstood by Milnes. This would explain why Nightingale kept weighing the pros and cons of marrying Milnes in her diaries over the next two years, and did not stop until June 1851, when Milnes became engaged to Annabel Crewe.

1850 to 1852: Training in Kaiserswerth and Paris

The Bracebridge couple set out on a trip to Egypt and Greece towards the end of 1849 , and Nightingale's parents allowed their daughter to accompany the couple one more time. Nightingale kept two journals during this trip: one apparently meant to be read by her family members, and a second in which she wrote down her growing despair over her meaningless life. During this trip, too, she visited a number of hospitals, including the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris , which was considered one of the world's best hospitals. The way from Greece back to Great Britain should lead via Germany. Selina Bracebridge, who supported Nightingale's plans, changed the route so that her companion could spend two weeks in the Kaiserswerther Diakonie . The change was made at such short notice that it was no longer possible to obtain permission from Nightingale's parents.

Nightingale was familiar with the work of the Kaiserswerth deaconesses , as Christian von Bunsen had been sending her the yearbooks of this institution since 1846. The institution founded by Theodor Fliedner was active in the care of prisoners, the upbringing and education of children and the care of the sick and the elderly. Deaconesses were also trained who wanted to dedicate themselves to the service of people from a Christian vocation and who received training in Kaiserswerth as nurses, community nurses, educators or teachers. Deaconesses did not take any vow comparable to the Catholic religious life and could leave their ministry at any time if they wanted to get married or return to their parents.

In a letter to her father, Nightingale described the Kaiserswerther Diakonie as “poor and ugly” and also noted that the cleanliness left a lot to be desired. But she also stated that diakonia was a model for Great Britain in all essential points. She was impressed by the weekly lecture that Fliedner held for the sisters, and by the strict rules that were supposed to ensure that the sisters behaved properly. In the wards for men, male nurses under the direction of one of the deaconesses looked after the patients, and the nurses were strictly prohibited from entering the wards for men after 8 p.m. She described the working method of Kaiserswerth Diakonie in her first publication, which appeared anonymously in 1851 under the title The Institution of Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, for the Practical Training of Deaconesses .

Since Nightingale first confronted her family with their desire to devote their lives to nursing in 1845, there had been a number of reform initiatives in Britain aimed at improving the education and standing of nurses. Selina Bracebridge took up this change in letters in which she supported Nightingale's wish:

"The world's opinion [...] has changed a lot ... Young women of a standing like Flo are now doing things that were previously unheard of ... They are no longer looked down on because they dedicate their lives to hospitals or patients."

In spring 1851 the ailing Parthenope Nightingale was prescribed a cure. While Fanny and Parthenope stayed in Karlsbad , Florence was allowed to spend three months in Kaiserswerth with the consent of their parents . However, the parents attached great importance to the fact that the daughter's internship would also be kept secret from close friends of the family. The main reason for her approval was that Florence Nightingale, after returning from her trip through Egypt and Greece, fell into such deep depression that her parents began to fear for their lives.

During the three months in Kaiserswerth, Nightingale learned how to care for wounds and how to manufacture medicines, accompanied the dying and assisted with operations. She returned to Britain with the confidence that she would succeed in realizing her life plans. Her parents finally gave in towards the end of 1852. She had always been against the idea, Fanny wrote to her sister-in-law Mai Smith, but gradually she saw that Florence would neither be happy nor contribute to the happiness of the family if she continued her life as usual.

Nightingale was allowed to return to Paris to study the workings of several hospitals and to continue her training in practical nursing with the Vincentians . But she broke it off in March 1853 to look after her dying grandmother.

1853 to 1854: Head of a nursing home

Shortly before leaving for Paris, Nightingale received an offer to run a nursing home in London, the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen. She accepted the offer on April 29, less than a month after her grandmother's death, and began work on October 12, 1853, just before the nursing home moved to a larger ward on Harley Street.

According to its founding statutes, the home, which was founded in 1850, was supposed to accept women from good families who, due to insufficient income, could not afford private care during a long illness. Most of the patients were governesses - one of the few respectable jobs a woman from one of the upper classes could take up. The house was also open to impoverished female relatives of pastors, merchants or officers. Nightingale received no salary; she lived on the five hundred pounds her father paid her as an annual pension. At that time a nurse earned about £ 20 a year, a governess with free board and lodging often only £ 10.

Many friends and acquaintances of the Nightingale family were amazed at the rather mundane task that the younger daughter took on after such a long struggle and intensive preparation. The 27-bed nursing home, which moved to a house on Harley Street when Nightingale began managing , allowed her to use some of the practices from the hospitals she visited. The reputation that the nursing home gained under her leadership led to her being discussed as head of the nurses at King's College Hospital as early as 1854 . This King's College education hospital was in one of the most populous slums in London, and the idea that she would work in this hospital and with the nurses there sparked her family's familiar reluctance.

The management committee of the nursing home, however, responded with understanding to her letter, in which she announced that she would give up the management at the end of 1854. It also gave her a leave of absence from her work during the severe cholera epidemic at the end of August 1854, so that she could look after cholera patients at the Middlesex Hospital .

1854 to 1856: Used in the Crimean War

Military background

The Crimean War broke out in 1853. Participants in the war were the Russian Empire on the one hand, the Ottoman Empire , France , Great Britain and, from 1855, Sardinia on the other . The Crimean War was the first modern trench warfare . It claimed numerous victims, to which epidemics and diseases as well as improper care of the injured played a large part.

The first troops left Great Britain at the beginning of 1854. As early as June 1854, the climatic and sanitary conditions in the Ottoman (now Bulgarian) port of Varna , where 60,000 British and French soldiers were waiting to be deployed, caused numerous cases of illness. The recommendations of the Commission of the Royal Army Medical Department previously sent by Andrew Smith to set up hospitals and sanitary facilities were largely ignored by the army command. As a result, more than twenty percent of British soldiers developed cholera, dysentery and other diarrheal diseases. More than a thousand British soldiers died before their units became involved in an act of war.

British troops were victorious in the Battle of the Alma on September 20, 1854, but here, too, the consequences of poor leadership, poor preparation and logistical incompetence became apparent. In contrast to the French troops, there were no carriers or wagons to transport the wounded from the battlefield. Wounded and sick people waited here for days or weeks for the ships to take them to Scutari - today's Üsküdar , a district of Istanbul on the Asian side - where the central military hospital for the war zone on the Black Sea was set up. The crossing from Crimea to the Bosphorus took between two days and a week, depending on the type of ship and weather conditions. The survivors were then met with a poorly organized transport to the central military hospital on a hill above the harbor.

Care for the sick and injured was probably no worse than during the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815, the last great battle in which the British Army took part. For the first time, however, there were war correspondents who used telegraph to inform the British public about the events in Crimea without any major delay . Drastic reports by Times correspondents William Howard Russell and Thomas Chenery about the inadequate supply stunned the British people. Chenery also confronted his readership with the question of why the French army was able to organize care for their wounded and sick with the help of nuns, while the British army was unable to provide such good care.

Travel preparations

In response to Chenery's reports, Nightingale had initially planned a private relief operation and had already obtained letters of recommendation from Home Secretary Lord Palmerston , Secretary of State Lord Clarendon and Andrew Smith, Director General of the Royal Army Medical Department. Nightingale's closest friends were the Herbert couple, whom she had met in Rome in 1850. Sidney Herbert held the post of Secretary of State in the British War Department in 1854, making him one of the most suitable people to support her in her planned mission. Her letter soliciting his support crossed an official letter from Herbert asking her, as Secretary of State, to take over the leadership of a group of nurses who were to travel to Scutari on behalf of the government. Herbert emphasized in his letter the experimental character that this company would have. Before the British Army set out for the Black Sea , the use of sisters had been discussed, but was almost unanimously rejected by the army command.

Nightingale originally planned to take only twenty sisters with her because she doubted finding a large number of qualified women and foresaw difficulties in leading a larger group. Eventually she agreed with Herbert on forty. In fact, it was not easy to find a suitable number of suitable women. The Institution of Nursing Sisters founded by Elizabeth Fry refused to turn off sisters because they were supposed to work under Nightingale's direction. The Catholic congregations reacted more accommodatingly, not least because at least a third of the soldiers fighting in the Crimea were Irish Catholics and because parts of the Catholic church leadership hoped to counter the anti-Catholic mood that was widespread in the British public. Fourteen suitable candidates were found among the volunteers who cared for the sick during the last cholera epidemic under the direction of the philanthropist Felicia Skene , and among the sororities of the Anglican Oxford Movement. Fourteen other sisters who were to travel with Nightingale were those ill-respected nurses who typically worked in hospitals in the UK. They were supposed to do the simpler work in the Scutari Military Hospital, while the nuns and volunteers were to take care of the sick directly. Letters to the editor that appeared in the Times these weeks show doubts in large parts of the British public as to whether the "Lady" sisters in Nightingale's group in particular are capable of accepting the brutal realities of a military hospital or even the harshness or profanity of a common soldier bear.

Arrival in Scutari

Nightingale set out for Scutari on October 21, 1854 with some of the sisters. Selina and Charles Bracebridge followed with the rest the next day. There was already friction in the group during the crossing, as the nuns in particular were disturbed by the manners and drinking habits of the nurses recruited from the hospitals.

The conditions Nightingale found in Scutari were, indeed, disastrous. The wounded and sick lay in poorly ventilated, unheated and rat-infested wards and corridors. The floors were dirty, the sanitary facilities inadequate, and because of the many diarrhea sufferers, there were also simple wooden buckets that stank unbearably on numerous wards . Many of the sick wore the same clothes for weeks, suffered from fleas and lice, had not been washed since their injury or illness and did not even have a simple straw mattress. There was a lack of pillows, blankets, plates, brooms, cutlery, scissors, towels, trays or wash basins and bandages.

Even during the Crimean War, a commission of inquiry was concerned with the question of how these conditions had come about: The Selimiye barracks , built at the beginning of the 19th century and made available to the British by the Ottoman government as a central military hospital, were pathetic Water supply structurally unsuitable for this. The cause of the poor supply was an excessive procurement bureaucracy. While the respective regiments with their shorter decision-making paths were responsible for the regimental hospitals, the supply of this first central military hospital of the British army was under a department of the finance department and not the war ministry. No fewer than eight departments of London ministries handled a single procurement transaction. This led to the absurd situation that London, for example, refused to buy shirts for soldiers who had been brought in directly from the battlefields without carrying baggage - with the remark that this would be an unjustified purchase.

Thanks to a fundraising campaign by the London Times , Nightingale had sufficient funds available to make decisions unbureaucratically. One of their first moves was shopping for thousands of shirts, drinking cups, and socks. Similarly, she was able to ignore the army’s official contract for washing bedding, bandages and clothes and set up a functioning laundry on site. She showed skill in dealing with the military doctors working in Scutari. At her first meeting with chief doctor Duncan Menzies on November 4th, she stated that neither she nor any of her sisters would enter any of the wards or care for a patient unless requested by the doctor in charge of the ward.

In principle, the younger doctors among the workforce were more inclined to work with her. It also played a role that the funds at her disposal enabled urgently needed purchases and her extensive connections in London gave hope that the necessary changes would be initiated. Because of her close ties to Sidney Herbert, some doctors suspected her of spying on the situation on behalf of the government.

Due to Nightingale's tactics, during their first days in Scutari the nurses were largely limited to making bandages and cleaning the parts of the hospital accessible to them. That changed on November 8, 1854, when the first wounded in the Battle of Inkerman arrived and it was foreseeable that hundreds more injured were to be expected. In consultation with the doctors, 28 nurses were assigned to the wards of the central hospital and another 10 to a neighboring hospital half a mile further north.

Organizational achievement

In the Battle of Inkerman, around 8,000 British soldiers had defended their position for over three hours against an attack by 35,000 Russian soldiers. Only then did the attack by French Zouaves and Foreign Legionaries force the Russian troops to retreat. 480 British soldiers died in this battle and another 1,859 were injured. Most of the injured soldiers, who landed in the hundreds in Scutari from November 8, were severely gunshot wounds, and many of them were already infected with maggots . Up until this point, none of the nurses had experienced a situation in which they had to face such massive injuries and such a large number of dying patients. “I expect to find two more dead when I go on my morning round; it would be eleven out of 30 [patients] in the last two days… ”one of the nurses wrote home.

Nightingale estimated that of the 38 nurses who had escorted her to Scutari, only between ten and sixteen were fit for the job. Concerned that their experiment might fail, Nightingale instructed none of them to enter any of the stations after 8:30 p.m. The nurses who had been recruited from London hospitals had to do their work under the supervision of one of the nuns. They were only allowed to leave the hospital premises in groups of three or under supervision; they were forbidden from accepting gifts as well as from fraternizing with the soldiers. Of both the original and later recruited volunteer and full-time sisters, Nightingale sent several back to the UK in the coming months for being drunk, incompetent and disobedient. Her strict leadership, which the historian Bostridge compares with the self-image with which a woman commanded servants in her social position, sometimes caused considerable dissatisfaction among the sisters.

Although Nightingale initially attended operations, she was mainly concerned with the organization of a basic hospital operation: She procured a sufficient amount of bed frames and bedding, had a wing of the hospital that was then unusable renovated and numbered all beds, and arranged the spacious staircases for everyone On the first floor of the treatment rooms, arranged that all wards were heated and there were enough zinc tubs to wash the patients, organized two kitchens in which special food for the sick was prepared, ordered the purchase of vegetables and, to counteract the common symptoms of scurvy , had boiled lemon juice served .

Peter Benson Maxwell, one of the members of the investigative commission who examined the care of the wounded on Herbert's behalf, wrote in a letter about Nightingale in view of this organizational achievement that she combined the delicacy and goodness of her sex with the cool clarity of a mathematician and was driven from their goal, do not shrink from any obstacle. Lord William Paulet, the commander in chief of the area where the military hospital was located, seriously considered transferring all procurement operations to Nightingale early in 1855. Nightingale never claimed to have significantly reduced the mortality rate in Scutari. Although this decrease occurred in the spring of 1855, it is certainly due to the lower occupancy rate and the better health of the newcomers. In her private letters to the Herbert couple, however, Nightingale claimed to have ensured a functioning hospital for their first four months. Bostridge believes this claim, which she never made publicly, is justified from today's perspective.

In the summer and autumn of 1855 the hospital in Scutari was largely occupied with minor illnesses and convalescents . While Nightingale was still recovering from the serious illness that she had contracted in the early summer of 1855 during a visit to the hospitals in the Crimea, she had reading rooms set up in the hospital and a café nearby, and organized series of lectures, musical evenings and theater performances . Her sister Parthenope organized writing materials, entertainment games, soccer balls, books, sheet music and the like in Great Britain.

Despite the War Minister Lord Panmure's assurance that no British soldier would give up part of his wages, Nightingale successfully continued the work of Reverend Sidney Godolphin Osborne: every Saturday afternoon soldiers could pay her part of their wages; the money was paid to their families in the UK. Because of their success, all these measures were also introduced in other hospitals; from January 1856, several government offices in Scutari and Balaklawa offered soldiers the opportunity to transfer money. Numerous letters of condolence from Nightingale to the relatives of deceased soldiers have also been received. Bostridge believes that Nightingale was the first time during a war with British involvement that someone in an official capacity addressed their bereaved relatives with so much care and compassion. As an example, he cites a letter from Nightingale to the mother of a soldier who died of dysentery , in which Nightingale wrote to the mother that her son had spoken a lot about her, that it was important to him that she found out that he was still entitled to pay, and that he finally died peacefully without much suffering.

The doctors who worked at Scutari had different opinions about the contribution of the nurses to the care of the patients: According to Arthur Taylor, they did a lot of useful work, but they were often in the way. In the opinion of the doctor Greig, a significantly larger number of such nurses would have been necessary in view of the large number of patients. In fact, there is no question that given the 4,000 injured and sick soldiers who were admitted to Scutari between December 17, 1854 and January 3, 1855 alone, the number of sisters was too few and most of the nursing work was done by the orderlies was done. Chaplain John Sabin pointed out, however, the positive influence that the sisters had on the morale of the patients.

Many found the nurses' treatment to be gentler and more comforting than those of the orderlies, who were also said to steal from their patients. In the fever delirium , many of the soldiers mistook the sisters for their female relatives at home: "They hold out their hand & say sister & mother," Charles Bracebridge described their death. The visit of one of the sisters was "like the visit of an angel", described one of the soldiers. This impression was also reflected in the letters of the soldiers to their families in Great Britain and significantly shaped public opinion about the work of Nightingale's sisters, as some of these letters were also published in the British press.

Conflicts in the nursing management

Because he misunderstood a note in a letter as a request for more sisters, Herbert sent a second group of sisters, consisting of 15 Irish nuns, 24 hospital recruits, and 9 volunteers, to Scutari on December 2, 1854. This group was led by Mary Stanley. Nightingale, who only found out about this three days before the arrival of the new sisters, saw her authority threatened, accused Herbert Wortbruch, offered him her resignation and initially refused admission. Any possible collaboration with the new sisters was made more difficult by Matron Frances Bridgeman's refusal to place herself and her nuns under the leadership of Nightingale as unconditionally as the Matron of the Bermondsey nuns had done.

In January 1855 some of these new sisters went to Balaklava, where the military situation had stabilized so that hospitals could be built there. There they were deprived of Nightingale's leadership because their government mandate only related to nurses who worked in British military hospitals in Turkey. The other sisters supported two hospitals in Kuleli, five miles north of Scutari, with the group divided into nuns on the one hand and nurses and volunteers on the other. The Irish nuns turned out to be experienced and good nurses. In the other group, initially led by Mary Stanley, problems arose due to the differences between the sisters, which Nightingale was unable to contain when Stanley returned to Britain sick in April 1855.

On April 20, 1855, Nightingale was expressly released from the leadership of the sisters in Kuleli, in particular because she accused the volunteers there of an unprofessional approach. Bostridge points out, however, that there is no difference between the Kuleli and Scutari hospitals, at least based on the death rate. The experience was repeated in the months to come: Nightingale was the official head of all British nurses working in Turkey, but was unable to exercise this claim to leadership due to the distances between the individual hospitals. Of the 229 or so Sisters sent by Great Britain during the Crimean War, only a small number worked under Nightingale's direction.

Nightingale's most staunch opponents included David Fitzgerald, who officially oversaw all procurement operations for the British hospitals, and John Hall, the chief military doctor. In early 1856, the latter denied the achievements of the Nightingale-led sisters in an official report. There were numerous errors in the report, and Nightingale considered reaching out to the House of Commons to deny the allegations. However, on Herbert's advice, she ultimately refrained from doing so. Within the War Department, she found an advocate in John Henry Lefroy , who believed envy and jealousy were two motifs in the report and advised War Secretary Lord Pemburne to hold on to Nightingale. In the general order of March 16, 1856 she was confirmed in her function. She is the first woman to be mentioned in a British general order.

Public perception

As early as October 1854, after Nightingale had officially been put in charge of the British sisters, reports about them had appeared in British newspapers and journals which historian Helen Rappaport described as hagiographic and Mark Bostridge presented a publicly acceptable alternative to the "angel im House ”, the image of a perfect wife and mother created by the writer Coventry Patmore .

On February 24, 1855, the Illustrated London News published an account of Nightingale visiting her patients in the wards with a lamp in hand during the night. This detail of her work, which was repeatedly taken up visually and linguistically in the weeks and months that followed, developed into part of her personal myth and became a metaphor for an ideal of Christian femininity that she represented in the eyes of the public. The few critical or mocking remarks that appeared in the satirical magazine Punch , among other things , went largely without resonance: Nightingale achieved a fame in Great Britain in the course of 1855 that was only surpassed by Queen Victoria.

As early as August 1855 there were plans to thank Nightingale for her work in the Crimea with a collection that would allow her to set up a nursing school on her return. Nightingale responded politely but not very enthusiastically. When asked to write down a first draft for the construction of such a school, she replied in a letter dated September 27, 1855: “There seem to be people who think that I have nothing else to do at the moment but make plans. “She told Selina Bracebridge that she might want to gain years of experience before taking on such a role.

The collection for the Nightingale Fund is considered to be the first British appeal for donations, which addressed all strata of the population. He was supported by a number of well-known personalities, among others the soprano Jenny Lind gave a benefit concert. General William John Codrington suggested that Army members donate a daily salary, and nearly a quarter of the £ 44,039 raised came from British Army personnel. Most of the donations came from members of the middle and upper classes.

1856 to 1880s: years of reform

Health and lifestyle

Nightingale's health had been compromised since her life-threatening illness in May 1855. Nevertheless, she did not leave Scutari until the end of July 1856, almost four months after the conclusion of the peace treaty between the countries involved in the Crimean War. In the third week of August 1857, she suffered a serious collapse in health. Your doctor diagnosed enlarged heart and neurasthenia . What she actually suffered from cannot be clearly established today.

A range of illnesses is discussed in the literature, ranging from Crimean-Congo fever , lead poisoning and syphilis to a purely psychosomatic response to her workload and her difficult relationship with her mother and sister. In 1995, the scientist David Young argued convincingly in the British Medical Journal that Nightingale most likely suffered from a particularly severe form of chronic brucellosis . This would conclusively explain the multitude of symptoms she had until the end of her life: irregular heartbeat, tachycardia , recurring fever, insomnia, depression and nausea.

From the autumn of 1857, Nightingale led the life of an invalid , who no longer appeared in public and was so ill at times that she herself was important figures for her reforms, such as Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone , General Charles George Gordon , the philanthropist William Rathbone and the Dutch Queen or close friends like Mary Anne Clarke could not receive. From December 1861 she suffered from spondylitis , shortness of breath and muscle cramps. Her health did not improve until the beginning of the 1880s, so that she was again able to cover longer distances on foot.

Nightingale lived for the first few years after her return from the Crimea in a suite in the Burlington Hotel in London's West End , then in quick succession in several houses rented in London. In 1865 her father bought her a house on London's South Street, which she lived in until the end of her life. Their household usually included a cook, a kitchen maid, two housemaids and a maid. Her private letters also mention the numerous cats she kept on South Street.

Working method and publicity

blue: those who died from infectious diseases

red: those who died from wounds

black: other causes of death

Nightingale's illness had a major impact on the way she worked. Unable to get an idea of the situation in a barracks, hospital or poor house for herself, she concentrated on collecting data, processing and analyzing it in order to then draw conclusions. Questionnaires were an essential tool for her, and she also made use of existing data. These included the official government reports , known as the blue books , as well as statements by British authorities. Their collection of material was so extensive that it made the multiple moves in the early 1860s much more difficult.

Nightingale was in correspondence with many people. In the four decades in which she was mainly concerned with reforms in India, this included Indian governors-general , members of the Indian National Congress and officers of the troops stationed in India up to members of the Indian middle class. Nightingale also had many relationships with British politicians and intellectuals. Prime Minister Lord Palmerston was a close friend of her family, Prime Minister Gladstone was her admirer, Sidney and Elizabeth Herbert , Benjamin Jowett , Arthur Hugh Clough and Harriet Martineau .

Some of the people with whom she has worked closely for decades include numerous experts such as the epidemiologist William Farr , the physician John Sutherland or the engineer Arthur Cotton . Like her, they were driven by the fact that they saw an urgent need for action. At the same time, working with her gave them the opportunity to exert an influence that went well beyond their usual sphere. Arthur Cotton, for example, who struggled to get a public hearing with his very far-reaching demands to expand channels, used Nightingale publications to present his ideas to a wider audience.

Nightingale regularly used her popularity, especially in the first years after the Crimean War, to exert pressure on politicians. Her threat to the War Ministry to publish her secret report on her experiences during the Crimean War is often quoted if the convening of the commission of inquiry is further delayed. The number of Nightingale's publications is very large. A characteristic of many of their reports is the visual preparation of statistical material, which also made it possible for those who were less mathematical to understand their conclusions. Her writing style was concise and occasionally sarcastic. It found a large readership because after its service in the Crimean War, it was considered a major authority on health care issues.

As a woman, she was never an official member of a government-appointed commission of inquiry. Due to her influence, however, these were partly occupied by people who were close to her and her reform ideas. For example, Sidney Herbert headed the sanitary investigative commission, and John Sutherland was one of the members. During the work of this commission, her suite in the London Hotel Burlington was jokingly referred to as the little war office because she received individual members there for consultation in the mornings and afternoons. The main driving force behind her committed support was her conviction that because of her illness she would not live long.

UK medical reform

Nightingale's return from her mission in the Crimean War went, as she wished, unnoticed by the public. On August 23, 1856, James Clark , Queen Victoria's personal physician, invited her to spend a few days in September at his house near Balmoral Castle . The invitation came at the request of the Queen, who was able to meet Nightingale informally. In her diary, the Queen noted about the first meeting that she had expected a "cold, stiff and reserved person" and that Nightingale's obliging and ladylike demeanor was pleasantly surprised. As a constitutional monarch , Victoria could not bring about reforms of the British medical system, but at her request, Nightingale extended her stay in Scotland to meet Lord Panmure, Minister of War, in Balmoral.

Contrary to what Nightingale had expected, Lord Panmure not only shared her view that the necessary reform steps should be initiated by a commission of inquiry. He also hired her to present her recommendations in a secret government report and to comment on the plans for Netley Hospital , the first central military hospital on British soil.

Nightingale's analysis for her government report revealed serious problems with military health care: Although British soldiers were typically between 20 and 35 years old, a low-mortality age group, they had a peacetime mortality rate almost twice that of civilians on. Nightingale found clear words for this in her report to the British government. If 11 out of 1,000 civilians died annually, but 17, 19 and 20 out of 1,000 soldiers of the line infantry, artillery and guards stationed in England, then that would be as criminal as taking 1,100 men annually to Salisbury Plain and shooting them there.

Your government report began with a fact-based description of what was going on in Scutari. Based on this, with the help of statistical analyzes, she derived what she saw as the essential steps to improve the living conditions of ordinary British soldiers: In addition to preventive hygiene measures, she emphasized the need for central military hospitals in addition to the regimental hospitals, and called for improved training and transport options for military doctors to get more qualified Recruiting personnel recommended appointing medical inspectors to report directly to the War Department and equipping military hospitals and barracks with adequate sanitation.

The commission of inquiry into the medical system began to publish its results in February 1858. It led to the establishment of a statistical office within the War Department, the establishment of a training facility for military doctors, a revision of the rules for military hospitals and a restructuring of the Royal Army Medical Department. Between 1858 and 1861 every British barracks and every military hospital was examined for the condition of the sanitary facilities, the supply of drinking water and the disposal of sewage and, if necessary, rebuilt.

The appointment of Sidney Herbert as British Secretary of War in 1859 simplified the implementation. However, after his death in 1861, construction work fell significantly again, because the Ministry of Finance protested against the high costs. Only towards the end of the 1870s did the outbreak of a typhus epidemic among soldiers stationed in Dublin lead to a renewed investigation of the living conditions of British soldiers and the initiation of further measures. As early as the 1860s, however, there was a clear decline in the mortality rate among British soldiers; towards the end of the 19th century it was well below that of the civilian population and, in the last decade of Nightingale's life, was only four to five men per 1,000 soldiers a year.

Early publications on hospital construction and care

Nightingale could no longer significantly influence the construction plan of the Netley Hospital, which opened in 1863. On her recommendation, however, at least the corridors of the central military hospital were expanded and more windows were installed. Your Notes on Hospitals (Notes to hospitals) , on which she had written parallel to the work of the Commission of Inquiry, published in the first and second edition in 1859. In it she recommended the installation of hospitals in pavilion style as for example in the Hôpital Lariboisière implemented in Paris had been. The hospital there consisted of individual wings that were only connected by a long corridor. She found support, among others, from George Godwin , one of the leading British architects, who described Nightingales Notes on Hospitals as essential specialist literature for architects.

In January 1860 appeared at the suggestion of Edwin Chadwick her nursing book Notes on Nursing: What It is and What It is Not (Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not) , she wrote for a group of people who at home sick to had to provide. John Sutherland read the first draft in February 1859 and recommended simpler English to Nightingale, suspecting that most of its readers would belong to the simpler classes of the population. The Notes on Nursing therefore features a concise, epigrammatic style with sentences such as “A nurse who makes a noise is the horror of her patients”. The book, only 76 pages long, received much praise in the British press. More than 15,000 copies were sold in the first two months, and her nursing book was in print throughout the Victorian Age .

As early as 1860 she revised the book and published versions that were aimed at different audiences. One version received additional information for professional nurses, and in 1861 the version Notes on Nursing for the Laboring Class appeared , which was linguistically simplified again and addressed a chapter to girls who care for their younger siblings at home had. French, German, Danish and Swedish translations appeared shortly after publication in the UK. The Notes on Nursing also found a large readership in the USA . During the Civil War , women made a significant contribution to the care of the wounded there, and Bostridge describes the veneration that Nightingale received there as almost cult.

Nightingale School of Nursing

By the late 1850s, Nightingale was not sure which form of nursing training would be most appropriate. That, along with her illness and her focus on reforming the British medical system, was one of the reasons the Nightingale Fund had not been touched until 1859. In the public the voices criticizing this increased, so that on June 24, 1860 the Nightingale School of Nursing was opened with 15 nursing students between the ages of 25 and 35 years.

Basically, what is now called the Nightingale system , the training model provided that the training of young professionals should be carried out by experienced nurses and not by doctors. Nightingale did not consider an extensive theoretical training with subsequent exams to be very effective, since from her point of view exams were only a test of memory and did not say anything about the performance of a nurse on the ward. Her training model placed an emphasis on hygiene. It also played a role that Nightingale was a supporter of the miasm theory until the beginning of the 1870s . In her opinion, cleanliness, proper ventilation and adequate nutrition cured most diseases. The training was not confessional, but the nursing supervisor should place value on the character education and moral strengthening of the future nurses.

London's St Thomas' Hospital was chosen as the training hospital , which was temporarily relocated shortly after the nursing school opened to be rebuilt elsewhere. With the move, the number of students rose to 38, who received varying salaries from the Nightingale Fund . In addition to the ordinaries , who received ten pounds a year in addition to board, lodging and service uniform, there were free specials , mostly daughters of clergymen who received little or no salary, and specials who paid 30 or 52 pounds for training. Schoolgirls committed themselves for four, later three years. For a year they were trained at St Thomas' Hospital, the remaining years they worked in a hospital selected by the Nightingale Fund .

After moving to the new building, Nightingale and the board of directors of the Nightingale Fund increasingly found that the nursing training by no means corresponded to Nightingale's expectations. Sarah Wardroper, who was also Nursing Director at St Thomas' Hospital and Nursing School director, was overwhelmed. The doctor Richard Whitfield, who had been paid for regular lectures by the fund since 1860, barely fulfilled this obligation. Of the 180 women whose education was funded by the Nightingale Fund between 1860 and 1870 , 66 dropped out prematurely. More than half of them were fired for misconduct, five of them for being drunk. Four other women died during training. A large number of the schoolgirls showed that their health was not in a position to fulfill their contract.

Some of the sick nurses suffered from syphilis , some were drug addicts ; an indication that Wardroper did not choose the students with the care Nightingale wanted. After lengthy negotiations with the hospital management, the surgeon John Croft was appointed instead of Richard Whitfield to give weekly lectures. Croft fulfilled this task until 1894, the series of lectures he had developed contributed significantly to the long-term success of the Nightingale Nursing School. The schoolgirls began to take part in autopsies, and a standard of care was developed for patients undergoing surgery, giving the trained nurses more responsibility. It is probably due to Croft that Nightingale recognized the miasma theory as wrong and now followed the theory of infection . In her publications in the late 1870s, she increasingly emphasized the value of antiseptic measures.

The different levels of education of the female students caused problems. Especially within the group of the ordinaries , who came from the lower class, many were not sufficiently literate and unable to take notes in the lectures. Therefore, they received additional reading and writing lessons two afternoons a week. However, the students living in a nurses' home were also looked after by a home sister who also took on part of the training.

Nightingale began to take more care of the students. The improvements in the standard of training soon showed success. By the early 1880s, nurses who had attended the Nightingale School of Nursing became nurses at a number of major hospitals in London and the provinces. There they established training programs for nurses similar to that of the Nightingale School of Nursing. The public attention that this training establishment received forced other UK hospitals to also establish training courses and improve the training of their nursing staff.

Reform of poor welfare

Nightingale's contribution to improving poor relief is closely linked to the targeted training of nurses. Since 1834, the British Poor Law made it mandatory that every person in need of assistance was assigned to a workhouse . The degrading, prison-like living conditions of the inmates, which Charles Dickens and Frances Trollope , among others, addressed in their novels, gave rise to a number of initiatives to improve poor welfare.

In January 1864, for example, the philanthropist William Rathbone approached Nightingale with an offer to fund a measure that would help improve nursing at the Brownlow Hill Workhouse Infirmary in Liverpool . Only work house inmates were treated in this hospital. There they were cared for by so-called pauper nurses, inmates who were still able to work and had no training in nursing. Nightingale suggested to Rathbone that the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary should pay for a care manager and twelve experienced nurses. Agnes Jones was selected as the nursing supervisor . Like Nightingale, Jones came from a well-to-do family. After long resistance from her parents, he had worked in the Diakonie Kaiserswerth and then went through the nursing training program at St Thomas' Hospital. Her start at work in Liverpool coincided with a scandal that drew public attention to the care of the impoverished sick: the death of 28-year-old Timothy Daly, an inmate at the Holborn Workhouse in London, was attributed solely to the filth he was in while his illness had left lying. In letters to Jones, Nightingale compared the situation Jones found in Liverpool with that in Scutari and admonished her that, because of this attention, her success could be the starting point for one of the most far-reaching reforms of her age. The report of the Administrative Commission just two years after Jones started working was positive. However, Jones died of typhoid in February 1868.

At the same time as Jones' assignment in Liverpool, Nightingale had offered cabinet member Charles Pelham Villiers , chairman of the Poor Law Board , a deployment of further trained nurses towards the end of 1864 to care for the sick in London poorhouses, as well as several very far-reaching reforms suggested. In London the sick were to be separated from the rest of the occupants of the workhouses, a central administration was to be responsible for all the poor in London, and welfare should be financed by a tax. This was intended to limit the abuse of office by the head of the poor, which led to serious grievances in individual workhouses, and at the same time ensure cost-effective health care.

Nightingale was aware that the poor legislation specifically tied public welfare to such unattractive conditions as admission to workhouses in order to limit the feared abuse. But the moment a caring poor fell ill, she argued, "He's no longer a poor ... [but] he becomes the brother of all of us & like a brother we should care for him." The New Metropolitan Poor Law was passed in 1867 in recognition of Nightingale's contribution. It did not go as far as Nightingale suggested, but provided for the establishment of special hospitals for the feverish and the mentally ill, who had previously also been admitted to workhouses. The newly created Metropolitan Asylums Board , which was funded by the city, was responsible for these hospitals . The act is considered to be the first step in the separation of public health care from public poor welfare and eventually culminated in the creation of the National Health Service , the UK's tax-funded health system that provides free medical care for everyone in the UK.

Reforms in British India

On May 10, 1857, there was a revolt of Hindu and Muslim soldiers against their British commanders in Merath . The so-called Sepoy Rebellion quickly spread across northern India. British troops largely suppressed the uprising during 1858, but disease severely affected the troops' ability to fight. So the first attempt to retake Lucknow had to be canceled because Henry Havelock only had 700 operational men. As Nightingale's later analysis showed, out of 1,000 British soldiers stationed in India, 60 died annually from causes related to unsanitary conditions.

In 1857, the British government again commissioned a commission of inquiry, this time to specifically examine the living conditions of the soldiers stationed in India. Nightingale dealt with health care issues in India from this point until the end of the 19th century, and during this time she developed into a recognized expert on India. The historian Jharna Gourday distinguishes four phases in Nightingale's preoccupation with India:

- from 1857 the attempt to achieve better health care for both members of the army and the Indian civilian population,

- From 1870 Nightingale focused on the causes of the regularly recurring famines,

- from 1879 she dealt with the Indian leasing system,

- from 1886 it concentrated on suggestions for improving health care in Indian villages and the education of Indian women.

Using their data analysis, Nightingale was able to show that the climatic conditions in India were not the real cause of the high mortality among British soldiers. The tropical climate only worsened the consequences of overcrowded barracks and inadequate drinking water supply and sewage disposal. The commission's recommendations were published in July 1863. The new Governor General and Viceroy of India John Lawrence , who was one of Nightingale's correspondents, had the British barracks rebuilt according to the recommendations at an expense of 10 million pounds and wrote her in 1867 that the number of annual deaths among British soldiers was 20.11 per 1,000 men. Nightingale, on the other hand, complained that reforms were being implemented far too slowly. In 1870 she published a paper entitled The Sanitary Progress in India , in which she accused the British administration of having made great efforts to build new barracks, but not sufficiently concerned with problems of drinking water supply and sewage disposal.

Famine and hydraulic engineering

Nightingale first became aware of the recurring famine in India from the famine in the Orissa region , which claimed approximately one million lives from 1865 to 1866. The British administration of the Bengal Presidency had underestimated the magnitude of the famine, misinformed the British Governor General of the situation and was unable to organize relief efforts at the height of the crisis. A British government inquiry led to the dismissal of the governor of the Bengal presidency, but the famine in Orissa was quickly followed by other famines. Today it is assumed that between 1858 and 1947, the years of direct British colonial rule over the Indian subcontinent , around 29 million Indians starved to death.

The numerous famines with climatic influences were officially explained, but the form of the British colonial economy actually meant that the majority of the population hardly had the subsistence level even in good years . Nightingale mainly focused on two topics: the construction of canals and irrigation systems and a reform of the Indian leasing system. Since the late 1860s, she had dealt with hydraulic engineering and had come to the conclusion that irrigation measures would sustainably increase agricultural productivity and that canals would at the same time significantly improve transport options within India. She was not alone in this view, individual measures had already been implemented during the indirect rule by the British East India Company . Your most important partner on questions of hydraulic engineering was the engineer Arthur Cotton , who was significantly involved in the 1850s in developing the Godavari into one of the main waterways on the Indian subcontinent.

In the 1870s, discussions about funding and the question of whether rail transport should be developed instead of building water canals prevented the expansion of irrigation systems and waterways. Nightingale's efforts to convince the cabinet members of Benjamin Disraeli's government to convene a commission of inquiry were in vain. Only after the famine of 1899, which exceeded the previous one in terms of extent and severity, did the Indian Governor General Lord Curzon convene a corresponding commission, which also recommended hydraulic engineering measures as an essential instrument for better supplying the Indian population.

Land rights and health care

Nightingale saw the cause of the poverty of the Indian rural population in the form of leasing. Land tenants, the so-called ryots , were largely unprotected from the arbitrariness of the zamindars , the large landowners. There have always been legislative initiatives aimed at restricting illegal rent surcharges, usurious interest rates and the possibility of eviction of leased land. But these measures remained half-hearted, since European planters as well as the Zamindars were affected by strengthening the rights of the rural population.

Nightingale's endeavors were focused on educating the British public about it and, despite attempts at moderation by her longtime friend Benjamin Jowett , she eventually publicly accused the India Office of disinterest in the living conditions of the Indian population. She associated great hope with the appointment of the liberal Lord Ripon as the new Governor General of India. His inauguration coincided with the publication of the Commission of Inquiry into the Famine of 1877–1878, which recommended a series of measures that Nightingale had promoted since the early 1870s and which Lord Ripon began to implement. Nightingale, who Lord Ripon referred to as his morale-booster , provided him with information and analysis on a wide range of topics. Lord Ripon's accomplishments include drafting the Land Tenancy Bill , which was supposed to strengthen the rights of the Ryots , the establishment of specialist agricultural departments within the British administration, the expansion of transport routes and the creation of reserves in order to be able to react more quickly in the event of famine. Lord Ripon finally resigned in 1884 because of the reaction to the Ilbert Bill submitted by him , which was supposed to expand the rights of the Indian population and, among other things, provided that Indians could also sit in court over British in British India.

Among the members of the Indian National Congress, Nightingale campaigned since the late 1880s for programs to familiarize the rural population with simple health care measures. She also worked closely with Lady Dufferin , wife of the Indian Governor General Lord Dufferin , whose foundation, known as the Dufferin Fund , was supposed to give Indian women access to medical care. The foundation established pharmacies and small hospitals. In addition, she set up wards in larger hospitals that only accepted female patients who were only cared for by women there. The main achievement of the Dufferin Fund consisted in the training of Indian nurses, midwives and doctors. Nightingale's most recent writings include simple primers on health care subjects that have been translated into various Indian languages.

Nightingale and women's emancipation

Although Nightingale chose a path of life outside the social conventions of her class and time, she was not an advocate of the emancipation of women. Historian Melanie Phillipps even describes her as one of her most determined opponents. In the Notes on Nursing , published in 1859, Nightingale opposed, among other things, the demands of women's rights activists to open medical studies to women. Elizabeth Blackwell , one of the first doctors to graduate from college, was one of her friends as early as the 1850s , and both of them occasionally considered working together more closely. In response to John Stuart Mill's critical remarks about Nightingale's attitude towards women's emancipation, she replied that women doctors try to be "men" but at best become third-rate men who have no influence on improving medical care. Both Phillipps and Bostridge see Nightingale's skeptical attitude towards the women's rights movement as rooted in their disappointment that only a few middle-class women could get them interested in nursing. Nightingale firmly believed that women had far more professional opportunities than they used. Her attitudes towards women doctors became less critical over the years, and the last two doctors to care for them were women.

Nightingale, while advocating the right to vote for women, considered it far less important than improving health care. Together with Harriet Martineau , Josephine Butler , Mary Carpenter , Lydia Becker and 135 other women, however, she is one of the women who signed the petition of January 1, 1870 to abolish the Contagious Diseases Acts . This petition, now considered a founding document of modern feminism , spoke out against criminalizing prostitutes while leaving their clients unmolested. The reason for the enactment of the law was the high number of British soldiers suffering from venereal diseases. Nightingale had already opposed this decree in 1864 because, from their point of view, it was not only immoral, but also completely unsuitable for reducing the number of sick people. From their point of view, a more effective measure was the creation of quarters for married soldiers and common rooms, which gave the soldiers the opportunity to spend their free time outside the entertainment district of the respective garrison town. As evidence, she referred to the example of the 5th Dragoon Guards , a cavalry regiment that had such facilities and had a significantly lower number of venereal diseases.

1890s to 1910: last years of life

From 1887 on, Nightingale suffered increasingly from visual difficulties and at the beginning of the 20th century was only able to write or read with great difficulty. From 1895 she also complained of increasing memory loss, and from 1896 she was largely confined to bed. She tried to keep working as long as she could and still took part in the attempt by Lord and Lady Monteagle to establish trained nurses in Irish workhouses. From 1898 onwards only the closest relatives were admitted to her; a companion and a nurse looked after her in her house on South Street.

It is not certain whether she was still aware that King Edward accepted her into the Order of Merit and that shortly afterwards the City of London awarded her the Freedom of the City award. She died in her sleep on August 13, 1910. Since she had refused an official national funeral at Westminster Abbey in favor of a private burial, Nightingale was buried in the family grave as requested. The transfer from London took place with great sympathy from the population.

Nightingale's grave is in the Church of St. Margaret's graveyard in Wellow, Test Valley, Hampshire.

estate

Nightingale's estate includes letters, copies of letters and draft letters, manuscripts, diaries, and notes. The collection of her personal records and documents kept in the British Library is the largest after that of British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone , filling nearly two hundred volumes.

Another extensive collection of sources on Florence Nightingale's life is in Claydon House , the Verney family home, into which Nightingale's older sister Parthenope married. Letters from Florence Nightingale to her parents and sister as well as part of the correspondence of the Nightingale family over a period of more than 100 years are stored here. The extensive collection is in part due to Parthenope Verney failing to grant her sister's request to destroy parts of her correspondence.

A third collection is in the London Metropolitan Archives , focusing on sources on the nursing school at St Thomas' Hospital . Sources on the life of Florence Nightingale are also kept in another two hundred archives worldwide. A total of 14,000 letters from Nightingale alone are known. The oldest is from 1827 when she was seven years old, the youngest letters are from 1907. This makes her life one of the best-documented of the Victorian era.

Medial retrospective

As early as February 1855, the German magazine “ Die Gartenlaube ” published its first - very benevolent - report on Nightingale's work during the Crimean War under the title Hospital-Scenen vom Kriegsschauplatze , which drastically and bluntly portrayed the catastrophic situation of the war wounded.

Nightingale's first biography was published as early as 1855. The thin, 16-page booklet that cost a penny described her early years in a way that was repeated in other biographies that appeared during her lifetime: her early proven sympathy for the Sick people, their care for the poor and their voluntary self-restraint despite their privileged family background. In 1893 some of her writings were edited by L. Seymer.

It was not until Edward Tyas Cook's biography, published in 1913 , that the traditional way of depicting Nightingale's life broke. Although he mentioned the typical narrative canon stories, according to which Nightingale had nursed her dolls "healthy" as a young girl and took care of the injured herding dog Cap, he emphasized his skepticism about the value of such reports, even if they were to be based on actual events. In a letter to Margaret Verney, the daughter-in-law of Nightingale's sister Parthenope, Cook didn't rule out the possibility that he might have overemphasized the more difficult aspects of Nightingale's character. He said it was important to differentiate himself as far as possible from the sentimental biographies that would have made her a “plaster of paris”.