History of East Timor

The history of East Timor encompasses developments in the area of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste from prehistory to the present. It is characterized by a long period of foreign rule. The Portuguese ruled the east of the island for 450 years , constantly harassed by the Dutch and the Topasse . Indonesia occupied the country nine days after East Timor was proclaimed independence in 1975 . Almost 200,000 people were killed as a result of the Indonesian occupation , which lasted 24 years. After three years of administration by the United NationsEast Timor was given independence in 2002. This made East Timor the first state to become independent in the 21st century. While internal conflicts caused new crises in the first few years, the country has stabilized since the collapse of the rebel movement in 2008. On December 31, 2012, the mission of the United Nations security forces and the International Stabilization Force ( ISF) ended. International troops and police officers were withdrawn. Since then, the country has experienced a significant upswing, which has been clouded by political disputes between the parties.

Mythical origin of Timor

According to legend, a young boy helped a baby crocodile find its way into the sea. In return, the crocodile took the boy on long journeys across the sea. When the crocodile died, his body became the island of Timor , which was colonized by the boy's descendants. Even today the crocodile has great symbolic importance in East Timor. It is traditionally referred to as “grandfather” and there is a custom of shouting “crocodile, I am your grandson - don't eat me” when crossing rivers.

Before the colonial era

background

The coastline of the Southeast Asian island world changed considerably over the millennia, which had an impact on possible settlements by immigrants. If the sea level rose sharply about 70,000 years ago, it fell about 30,000 years ago during the last glacial maximum . About 18,000 years ago the sea level rose again and land masses such as Sundaland and Sahul were again divided by the water. Further major changes in the coastline took place 14,500, 11,500 and 7,500 years ago, creating today's island world and the continent Australia, which is separated from Asia . Despite this erratic change in geography, Timor has remained an island all along with no land connection to the rest of the world. Only the distances to be overcome shrank considerably at times.

The people of Timor came to the island as part of the general settlement of the region. Anthropologists assume that the descendants of at least three waves of immigration live here, which also explains the ethnic and cultural diversity of Timor. Interestingly, all ethnic groups in Timor refer to themselves as immigrants who originally moved to the island from elsewhere. According to myth, the earlier the immigration took place, the higher the status in the traditional power structures on Timor.

The Timorese peoples originally knew no script. Hence, there are no written records of history before European colonization . There is a rich tradition of oral traditions, such as that of the Bunak people in the center of the island. The stories were recited in repetitive rhymes and alliterations . In every village, the elders taught the young people the legends of the clan, but there are also the Lian Nain (roughly lord of words ), bards, and ceremonial dignitaries who can recite verses for hours. Most often, two-line verses are used, with each line made up of two sentences. The first sentence of the second line repeats the content of the last sentence of the first line in other words. The languages are rich in metaphors and symbols from the animistic culture of Timor. Legends such as the creation myth of the crocodile were also depicted and used decoratively.

It is sometimes not easy to collect local knowledge about history. In Oe-Cusse Ambeno there are traditional restrictions on the transmission of historical knowledge. This is usually only allowed for two or three people in each village. However, they are only allowed to report on the history of their own village, you are not allowed to tell anything about the history of other villages, if this is known at all. Even today, many of the inhabitants of Oe-Cusse Ambenos do not leave their village for almost all of their lives and at best only know the neighboring villages. The consequence is that the information often contradicts each other from village to village. No information about the past may be given about two specific villages in the municipality . There is a taboo about this. If you want to find out information about the history of the local empire, there are only a few who are allowed to provide information.

The first settlers

The oldest traces of human settlement on Timor are between 43,000 and 44,000 years old as of 2017. They were discovered in the Laili cave near Laleia ( Manatuto municipality ). In 2006, traces of 42,000 years old were found in the Jerimalai limestone cave near Tutuala in the far east of Timor. In addition to stone tools and mussel shells, which were used as jewelry, the remains of turtles, tuna and giant rats were found that had served as food for the cave dwellers. These findings support the theory that Australia was settled via the Lesser Sunda Islands . There seem to be no more traces of this wave of settlement in the present-day population of Timor. Half of the remains of the fish come from species that only live in the high seas. This proves for the first time that people were able to fish far away from the coast 42,000 years ago. In addition, a fish hook about four centimeters long was found , which was made from the shell of a sea snail . It is estimated to be between 16,000 and 23,000 years old, making it the oldest known fish hook in the world. The hook was used to catch fish in the coastal waters, which at that time became richer in fish due to the formation of the coral reefs. Small plates with holes drilled from the shell of the common pearl boat (Nautilus pompilius) , the oldest known pieces of jewelery in East Asia and the Pacific region, are 38,000 to 42,000 years old .

A 35,000-year-old piece of bone was found in Matja Kuru , which was used to attach harpoon tips to the wooden shaft. It is the oldest evidence of this complex binding technique, which is known throughout Australia and Melanesia, but the oldest evidence of which was only a few hundred years old.

Archaeologists have also struck gold in other caves near Tutuala. Settlement remains were found in the Lene Hara cave , which have been dated to between 41,000 and 43,000 years ago. The multicolored murals depicting boats, animals, and geometric structures are only 2000 years old. The paintings in the O Hi and Ile Kére Kére caves are estimated to be 5000 years old, the stone engravings showing faces are even estimated to be 10,000 years old. Further rock paintings can be found on the cliffs of Tutuala and Tunu Taraleu , in Lene Kici , Lene Cécé and Vérulu (all near Tutuala), in Uai Bobo (in Venilale , Baucau municipality ), Lie Siri , Lie Kere , Lie Kere 2 and Lie Baai (on the high plateau of Baucau ) and in the region of Baguia (also municipality of Baucau).

There are basically two zones in the rock paintings: those on the Baucau plateau and those in the vicinity of Tutuala . Pigments in black, red, yellow and green are used for a variety of motifs: lines and geometrical figures, circles surrounded by rays (referred to as suns or stars), lifelike and X-ray-style images of animals, people, anthropomorphs and boats. Most of the pictures are but the Neolithic " Austronesian attributed painting tradition" (Austronesian painting tradition APT). On the northeastern Kisar there are wall paintings, some of which show striking similarities to paintings on the eastern tip of Timor. They are more than 2500 years old and suggest that there was already close contact between the two islands at that time.

In addition, some hand outlines are known, in which the artist pressed his hand onto the rock as a template and blew pigments over it. Such handprints are less common here than in neighboring regions, which is a special feature of the rock paintings on Timor compared to the other islands in Southeast Asia. O'Connor grouped hand stencils next to simple red-figurative, filled-in motifs in a series of portraits, which differ from the APT due to their location in deeper but accessible cave parts. Until 2020, however, there were no indications that these images came from a different era. Then hand outlines of the Lene Hara cave were described for the first time, probably from the Pleistocene . They resemble portraits in Australia and also support the theory of the settlement route of Australia via Timor in terms of their estimated age.

What is striking is the extensive lack of motifs of large animals, as often occurs in rock art from the Pleistocene. This can be explained by the fact that large animals are largely absent from Timor’s fauna . The resident dwarf form of a stegodon died out well before the first humans arrived on the island.

The Australo-Melanesian immigration

It is believed that Australo-Melanesian peoples (also called Vedo-Austronesian ) were around 40,000 to 20,000 BC. Reached Timor from the north and west during the last ice age. At that time, the Great Sunda Islands were connected to the Asian continent by land bridges and the way across the sea to Timor was significantly shorter. Their descendants, the Atoin Meto (Atoni) , probably represent the original population of Timor and are characterized by very dark skin and straight, black hair. They make up the majority of the population in the west of the island, also in the East Timorese exclave Oe-Cusse Ambeno .

Genetic studies published in 2015 suggest a wave of immigration from the east. According to these results, the first settlers moved from the west to New Guinea 40,000 to 60,000 years ago, and 28,000 years ago people returned to Timor from New Guinea (see map A on the right). Further genetic evidence suggests the immigration of other groups who moved from Taiwan to Timor 4,000 to 8,000 years ago (Map B). A third proven group probably came from today's island of Borneo and reached Timor 10,000 years ago (Map C).

If one assumes that the pirogue was not used until 7000 BC. Was invented, one can assume that the stretches across the sea were made with rafts . The people lived together in small clans or tribes who moved around as hunters and gatherers without permanent settlements. Already 9000 years ago people brought the Gray Couscous from New Guinea to Timor, which became the main prey of the local hunters.

The Melanesians

Around 3000 BC Melanesians came from the west with a second wave of immigration and brought the oval-ax culture to Timor. Pottery, hatchets and shell pearls appeared for the first time on Timor during this time, and traces of agriculture can be identified. Were introduced millet , Gourd , coconuts and other fruits. The remains of domestic dogs and pigs can also be found on the eastern tip of Timor for the first time from the same period. After the arrival of the Melanesians, the Vedo Austronesians withdrew into the mountainous interior of the country without any major intermingling.

The direction of immigration from the west is surprising, as the descendants of these immigrants are related to the ethnic groups in Papua New Guinea , Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands in the east. These regions were settled by the Melanesians 30,000 to 40,000 years ago. The Melanesians in Timor include the Fataluku , Makasae , Makalero and Bunak. Their languages belong to the Papuan languages .

However, recent linguistic studies suggest that at least the Fataluku settled on the eastern tip of Timor only after the Austronesian immigration from the east. There they have almost completely assimilated the local Malayo-Polynesian Makuva over the past few decades . Such a scenario is also speculated among the Makasae.

The Austronesians

There are different statements as to the number of waves in which the Austronesians reached Timor.

Austronesian groups from southern China and northern Indochina probably reached Timor around 2500 BC. They spread across the Malay Archipelago under the pressure of the expansion of today's East Asian ethnic groups . About 1000 to 2000 years ago, metal processing began on Timor. At the same time, the local giant rats, such as the Musser Timor rat ( Coryphomys musseri ) , probably died out. It is assumed that with the introduced metal tools, large areas of the island were deforested for the first time, which led to the extinction of the giant rats, which are popular as prey. Australian and Portuguese researchers were able to prove the existence of a prehistoric copper industry on Timor. Pits and simple tunnels were discovered in which copper ore was mined, and artifacts confirmed the smelting and manufacture of copper tools on the island.

Some scientists assume that around 500 AD more Austronesians, who were more clearly influenced by East Asian influences and who became the dominant population group in the entire archipelago, also reached Timor. This ethnic group is unmistakable on the main islands of Indonesia, but there is still no agreement on the original population on Timor, but it has a much more Asian appearance than the original Austronesian immigrants.

It was not until the 14th century that the Malayo-Polynesian Tetum immigrated to Timor. Today, with 100,000 members, they form the largest ethnic group in East Timor. According to their stories, they come from Malacca , from where they came to Timor. First the Tetum settled in the center of the island and displaced the Atoin Meto in the western part of Timor. Later they also advanced into the eastern part and founded a total of four empires, of which Wehale was the most powerful.

Merchants and kings

In 2015, when a house was being built on the Raumoco River in Suco Daudere (Lautém municipality), a bronze drum from the Dong Son culture (around 800 BC to 200 AD) from what is now Vietnam was discovered . The 80 kg heavy and approximately 2000 year old artifact is one of the best preserved of only about 20 bronze drums that were found along the ancient shipping lanes in Southeast Asia. The top piece of such a drum was found in East Timor before 1999. A spout hatchet from the Dong Son culture was discovered near the town of Baucau .

Hinduism came to Timor in the 1st century AD and Buddhism from the 5th century. Neither of them left much of a mark.

Although some Indonesian publications of the 1970s state that Timor belonged to the Srivijaya Empire (7th century to 13th century), there are no sources to prove this. Even Bali and the east of Java did not belong to this empire, although they were west of Timor and were Hindu and Buddhist. Presumably, Javanese kingdoms prevented the Srivijaya Empire from expanding eastward. Possibly, however, merchants reached Srivijayas Timor. Dutch historians report that Timorese sandalwood was transported through the Malacca Strait to China and India as early as the 10th century .

In East Timor there are several hills with the remains of stone fortifications that once protected settlements. It is believed that these fortifications were built during times of climatic changes. Some emerged around AD 1000 when rains became less frequent and the environment changed dramatically. Other remains of the wall are dated to the time after 1300 AD, when the change to the Little Ice Age began. In both periods there was probably a scarcity of resources due to climate change and increased conflicts between different groups, although other reasons for the new need for fortified settlements may also have existed, for example the emerging trade in sandalwood.

The Chinese overseas trade official Zhao Rukuo named Timor a place rich in sandalwood in 1225. The sandalwood tree (Santalum album) is not only found on Timor, but also on various Pacific islands , Madagascar , Australia and India, but only Timor, Sumba and Solor provided the highest quality of white sandalwood .

In addition to Malay and Chinese traders, Arab traders later traveled to Timor to buy sandalwood, slaves and honey , which they exported via Java and Sulawesi to China and India. Beeswax for batik dyeing in Java and later for the local Catholic Church as candle wax was another valuable commodity. As local trade flourished, local royal families emerged. The traders did not settle on Timor, which is far from the trade routes between China, India and the large islands, but only stayed as long as they had to to do their business.

In 1292 the Mongols failed with an invasion of Java. Out of the successful defensive struggle, the Hindu-influenced Majapahit Empire emerged, which reached its peak in the middle of the 14th century. In the Nagarakertagama , the heroic epic of that time, a long list of tributary vassal states of Majapahit is given. Timor is one of them. However, the Portuguese scribe Tomé Pires noted in the 16th century that all the islands east of Java were named Timor, as the local language uses the word "Timor" to denote the east. Even today, "East" in Bahasa Indonesia means timur . Be that as it may, after a century, Majapahit's power fell apart due to disputes between the Hindu princes and the spread of Islam in Malaya , north-east Sumatra and north Java. In 1409 the king of Malacca converted to Islam. Other rulers on Sumatra, Kalimantan , Java, the Moluccas and the Philippines followed. This change did not reach Timor. Muslim Malacca gained power, so that the Javanese ports also lost importance. The Chinese traders disappeared almost simultaneously between 1368 and 1405. The reason was China's self-chosen isolation from the outside world . When China banned its traders from foreign trade for a second time between 1550 and 1567, the Portuguese initially took over the trade routes between the Middle Kingdom and Timor.

The earliest European explorers reported a number of small tribal areas and empires in Timor, created through trade and ruled by Liurais , the traditional rulers. The population lived primarily from slash-and-burn farming . The relationships between these domains were extremely complex through rituals, marriage, and trade. According to legend, all peoples descend from an ancestor who divided the island between his three descendants into a west, an east and a central area. In the center of the island stood the empire of Wehale with its allies among the tribes of the Tetum, Bunak and Kemak tribes . The Tetum formed the core of the empire. The capital, Laran, in what is now West Timor , formed the spiritual center of the entire island. The west was dominated by Sonba'i , the east by Likusaen (today: Liquiçá ) or Luca . This ritual hierarchy of the individual empires and the placing in front of Wehale, Sonba'i and Likusaen did not mean any real power, but the prestige of the three rulers could support the formation of alliances.

Antonio Pigafetta , a member of the Magellan Expedition , visited Timor briefly in 1522. He reports that there were four main Timorese kings who were brothers: Oibich, Lichisana, Suai and Canabaza. Oibich was the chief of the four. Oibich could be assigned to Wewiku , which is referred to in later sources as the Wehales base. Suai is the capital of today's East Timorese community of Cova Lima and probably formed a double empire with Camenaça (Kamenasa, Canabaza, also Camenaça or Camenasse). Lichisana is equated with Liquiçá. Since Lichisana and Suai-Canabaza Wehale had to pay tribute and all these empires were in the center and east of Timor, they were later summarized by the Portuguese as the province of Belu (also: Belos or Behale ). Iron was known, but no script was in use. The population practiced traditional, animistic practices .

Western Timor was named Servião after the dominant Sonba'i ( Dutch : Zerviaen or Sorbian ). In 1563 Servião first appeared as Cerviaguo in the reports of the Portuguese as an important trading point for sandalwood on the north coast of Timor. However, since there is no place there to which this name can be assigned, it is assumed that this was an outpost of Sonba'i, which first appeared on the Portuguese map of Manuel Godinho de Erédia in 1613 as the Kingdom of Servião . Servião consisted of most of the Atoin-Meto area in West Timor. Luca can also be found on the map in the far east, especially highlighted.

The tribes on the western edge of the area of influence of Wehale simultaneously maintained alliances with Sonba'i and Oecussi , the tribes in the east with eastern Timor and its centers Atsabe and Lospalos . In this way, from the point of view of many Timorese, the island formed a unit that was only destroyed by the colonial split between the Dutch and the Portuguese (see Mandala (political model) ). From this arose the concept of " Greater Timor " in the 20th century , which propagated the unification of the island in one state. Despite the many ethnic and linguistic differences between the people of Timor, their social structures were very similar, which made contact between the peoples easier. But this should not hide the fragmentation of the island. A Portuguese list from 1811 lists a total of 62 kingdoms in Timor (16 in Servião and 46 in Belu). Ultimately, the number cannot be precisely fixed, as it was constantly changing due to wars, mergers and splits, and some empires were subordinate to others.

The population of Timor was divided into different social classes, the lowest of which were the slaves. Some of these were also traded, so that in the 17th century Timorese slaves also got to Makassar and from there to Palembang , Jambi and Aceh as well as to the pepper plantations on southern Borneo . At this time, however, Batavia , today's Jakarta , became the main customer . Almost every ship that reached the port from Timor had slaves on board. The Dutch and Portuguese operated a slave trade well into the 19th century, which also affected the neighboring islands. So the topasse also caught people as a commodity on Roti .

The introduction of maize as a food crop in the middle of the 17th century had a major impact on the Timorese population, because the otherwise common, labor-intensive cultivation of rice field terraces (sawah) was only possible to a limited extent. The population growth also depended on the availability of valuable resources such as sandalwood or honey. Trading with them boosted local wealth. Paradoxically, before foreign trade began, sandalwood had no use or significance for the Timorese.

Island of the headhunters

Oral traditions from the Atsabe Kemak from the Ermera community tell of feuds , wars, conquests and headhunters . Such outbreaks of violence arose for a variety of reasons, such as the dispute over fertile land, borders, wedding agreements or just perceived disregard. Every year battles broke out over areas with bees in order to secure the valuable commodity beeswax. Sandalwood was also coveted and contested for trade. Even between the individual village communities ( sucos ) that were ruled by a dato , there were fights over arable land, because no Timorese were allowed to cultivate land in the neighboring territory, because then on the one hand the tribute to the dato and on the other hand the jurisdiction could not be assigned in the event of a dispute. This meant that especially sucos with high population pressure always tried to enlarge their areas. The constant conflicts gave rise to a culture of ritual warfare, which in Timor is called Funu . Around Tutuala there are still remains of several old fortifications ( Portuguese : Tranqueira , fataluku : lata irinu ), with which the Fataluku protected their settlements.

One could not go to war without the consent of the ancestral spirits . For this purpose the priest ( Dato-lulik ) sacrificed a buffalo and questioned the spirits. One could only go to war if the spirits regarded the cause of war as justified. If the spirits did not accept him, one had to change the reasoning until the spirits agreed. Then each man had to slaughter a chicken in front of the priest . If the chicken stretched its right leg up, the man would have to go into battle; if the chicken stretched its left leg, it was meant to protect women and children at home. The latter could consult the oracle a second time if they wanted. If you were then allowed to fight, but there was a high probability of being wounded or killed, while the elect from the first round were, according to the faith, invulnerable to all weapons.

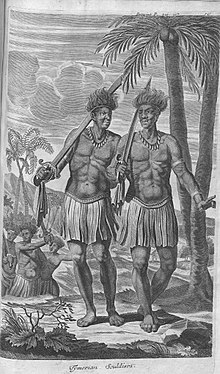

Before a battle, the magnificently decorated so-called Meos stood in front of the warriors and began to stir up the atmosphere with war dances, to extol the courage of their tribe and to insult their opponents. Then they withdrew and the opposing parties began shooting at each other from a great distance - initially with a bow and arrow, later with firearms. As soon as a man was killed in the process, the fight ended. This type of warfare seemed strange to European observers of the time, but field battle was not the main objective. The actual war consisted more of ambushes and raids, in which the attempt was made to capture as many heads as possible of opposing warriors, women and children as slaves and cattle, and sometimes also to devastate the opponent's land. Women were only beheaded when they tried to flee from villages that had already been conquered, as this was contrary to morals.

The returning warriors were greeted by the women with the traditional Likurai dance, in which the captured heads were displayed. Those who captured a head were honored, with those heads captured in battle bringing more honor than those caught in an ambush. The successful headhunters received the title Assuai (the brave) . The head trophies were cleaned, dried and then hung in the hut of the Assuai. The head had to be offered something to eat at every meal. Eventually the head was given to the Liurai or Dato who kicked him during a victory ceremony. As a sign of victory, the Assuai was given a bracelet or a metal, round breastplate ( belak ), which he wore around his neck.

The captured heads were carefully kept so that if a peace agreement was made, they could be returned to the dead man's family with great weeping and lamentation. If a head was missing, substantial compensation had to be paid. After a peace agreement, neither side harbored grudges against the other. The peace was usually strengthened with a wedding or with blood brotherhood. This then required armed support in the event of war.

Headhunting and internal battles did not end until the Portuguese finally had unrestricted rule over the country after the suppression of the last rebellion in 1912 and were able to prevent hostilities between and against the Timorese.

Scientists, based on research in New Guinea , where similar traditions existed, see a form of population control in the strongly ritualized wars - not primarily through the victims of the war, but through the devastation of the cultivated areas. Slash and burn zones had to be abandoned by the losers before the soil was depleted, and the victors could not use them immediately for fear of the revenge of the ghosts and taboos. The now fallow areas had the opportunity to regenerate. In addition, the form of war increased the child mortality rate among girls, which is why - also due to the low number of victims among the warriors - the balance between the sexes was kept regionally. The more warriors an empire had, the better it could protect its population and expand its territory. Male offspring were therefore of great importance.

Portuguese colonial times

Arrival of the Portuguese

The Portuguese Afonso de Albuquerque conquered the Sultanate of Malacca on August 15, 1511 . This made Portugal an important base for trade with the Lesser Sunda Islands and especially the Moluccas, the main goal of Portuguese expansion in Southeast Asia. In order to find the islands known as the Spice Islands, an expedition of three ships was sent in the following November under António de Abreu , who had already distinguished himself during the conquest of Malacca. After reaching the Moluccas, the ships turned to the southwest and in 1512 were the first Europeans to reach Timor, Solor and Alor (Ombai) . It is not certain whether the Portuguese entered Timor at that time. Documents from the beginning of colonization were lost in a fire in the Dili archive in 1779. Some historians believe that the discovered Timor was only noted on a map and a landing only occurred on the island of Solor, northwest of Timor. A Portuguese settlement is said to have been founded here, the nucleus of the Portuguese colonies on the Lesser Sunda Islands. Timor appears for the first time in a Portuguese document dated January 2, 1514. In a letter to King Manuel I , Rui de Brito Patalim mentioned the island. It is certain that the Portuguese first landed on Timor by 1515. A plaque on a replica Padrão dos Descobrimentos marks the place in Oe-Cusse Ambeno , where Portuguese Dominicans entered Timor as missionaries on August 18, 1515 . For the 500th anniversary, the Lifau Monument was inaugurated, with a replica of a caravel and life-size, bronze figures that recreate the encounter between the Portuguese and the Timorese. It is unusual that there are no reports of any occupation of the island by the setting up of a padrão. More detailed descriptions of the island are also missing until Pigafetta landed on January 26, 1522 on board the Spanish ship Victoria near Batugade and stayed for 18 days.

In 1556, the Portuguese settled on Timor for the first time in the area of today's East Timorese exclave Oe-Cusse Ambeno. Here, as on the neighboring island of Solor, the Dominicans founded a settlement to secure the sandalwood trade. In Timor it was the place Lifau (Lifao) , 6 km west of today's Pante Macassar . At the same time, the Dominican António Taveira began proselytizing Timor. The focus was on the kingdoms on the north and south coast in the late 16th century. In 1566 a fortress was built on Solor, which became the center of the surrounding trade. Solor had the advantage that, unlike Timor, there was no malaria here. Apart from the missionaries, most of the Portuguese did not yet settle in Timor, but instead called at various points on the island, such as Kupang , Lifau or Mena (east of today's Oe-Cusse Ambeno). Sandalwood was exported annually from Timor via Solor, mainly to Macau . Macau was the link to Portugal, even if Goa was officially the competent administrative center for Timor during most of the colonial period .

In the 16th century, the trade routes were heavily dependent on the season. The caravels left Goa in September with the monsoons blowing southwards . From Malacca Indian goods were then exchanged for Chinese copper coins in Java. For this, further east on Sumbawa rice and simple cotton fabrics were obtained, which in turn were exchanged for spices on the Banda Islands and Ternate . Some of these commercial travelers also came to Solor and Timor to purchase sandalwood. Between May and September one returned to Malacca with the southwest monsoon. The fact that the ships had to wait a long time at Solor and Timor due to the wind conditions favored the establishment of permanent settlements. At the end of the 16th century there were Portuguese bases in Lifau, Mena and Kupang. The first church on the island was built in Mena in 1590. The profit was evident. For a picul (62.5 kg) of sandalwood, the equivalent of five réis was paid in Timor in 1613 . In China you could get 40 Réis for a picul.

Initially, the Portuguese had no administration, military garrisons or trading posts on Timor. These were built up gradually in response to the threat posed by the Dutch, who continued to expand their influence in the region. In the first years some soldiers were hired under a captain for Solor. From 1575 an armed ship with 20 soldiers was stationed here and from 1595 Goa officially assigned the post of captain, who took over the duties of governor for the region - much to the displeasure of the Dominicans, who saw their rights restricted. The first Capitão Goa was Antonio Viegas.

In 1586 large parts of Timor were declared a colony of Portuguese Timor . Portugal now also used the colony as a place of exile for political prisoners and ordinary criminals. This practice continued into the 20th century.

Race for Timor

On April 20, 1613, the Dutch under Apollonius Schotte conquered the fortress on Solor. The Portuguese evaded to Larantuka in the east of Flores . Solor changed hands several times over the next few decades, while Larantuka became the new Portuguese center of the region. From Larantuka, the Topasse controlled the trade network in the region, especially the lucrative sandalwood trade. The topasse, also called Bidau, Larantuqueiros or black Portuguese , were descendants of Portuguese soldiers, sailors and traders who married women from Solor and Flores. According to Dutch reports, the Topasse ruled the ports on the north coast of Timor from Larantuka as early as 1623.

On June 4, 1613, the Scots landed in Mena. The rulers of Mena and Asson were moved to form an alliance with the Dutch and guarantee supplies of sandalwood. After that, Schotte drove further along the coast and concluded several treaties with local rulers, which later formed the basis of all Dutch claims in West Timor. Finally he also conquered the Portuguese fort near Kupang and left behind a small occupying force, just as in Mena. But in 1615 the Dutch gave up Solor, and in 1616 their bases on Timor and Flores.

With the restoration of independence from the Spanish crown in 1640, Portugal was able to become more involved in Southeast Asia again. However, a revolt of the Macassars against the Portuguese broke out and Karrilikio (also called Camiliquio or Karaeng Makkio ), the Muslim sultan of Tallo (Tolo) on Sulawesi , attacked the north and south coast of Timor with a total of 150 ships and 7,000 men. After three months of raids, he withdrew. When António de São Jacinto , Dominican and Vicar General of Solor, reached Mena with a force, he found the place destroyed. The Muslim occupation fled inland. The dead king had been replaced by his wife. With their support, the Portuguese regained control of Mena in 1641. The queen and her people converted to Christianity . The Liurai of Amanuban (Amanubang) , a brother-in-law of the Queen of Mena and ruler of the area around Lifau, also converted to Christianity and had several churches built. On May 26, 1641 Francisco Fernandes defeated a force of the Liurais von Wehale on the border with Mena. The Portuguese then began a large-scale military operation under Fernandes to extend their control to the interior of the island. This procedure was justified with the protection of the Christianized rulers of the coastal region. The previous Christianization supported the Portuguese in their quick and brutal victory, as their influence on the Timorese had already weakened the resistance. Fernandes carried out the campaign with only 90 Portuguese musketeers. But he was supported by numerous Timorese warriors. Fernandes first moved through the area of Sonba'i and by 1642 conquered the kingdom of Wehale, which was considered the religious and political center of the island. Members of the Wehales royal family fled to the east and married into ruling families there. Many noble families therefore still claim their descent from Wehale today, even if this is in part very questionable. Several rulers in West Timor subsequently converted to Christianity and swore an oath of loyalty to the Portuguese crown, for example the ruler of Kupang. Timor was then given the name Ilha de Santa Cruz (Island of the Holy Cross), which the island kept for a long time. By 1640 a handful of priests had already founded ten missions and 22 churches in Timor. In 1644 the Liurais of Luca and Açao were also Christianized. In 1647 António de São Jacinto was also Vicar General for Timor. In 1698 the Dominican Manuel de Santo António came to Timor. Through his successful missionary attempts around 1700, Luca and his neighboring empires in the southeast of the island also came under Portuguese influence. 1701 he was by Pope Clement XI. appointed Bishop of Malacca and resided in Lifau until 1722. Manuel de Santo António is therefore considered to be the first bishop in Timor. Missionary work and economic interests went hand in hand. The Dutch, on the other hand, had no problems working with rulers who also used violence against the Christianization of Timor.

Supremacy of the topasse

After the victory against Wehale, the immigration of the Topasse increased further. By 1642 a large number of Topasse were already living in Timor, the center of which became Lifau, the main Portuguese base on the island. Their leader, who later carried the title of captain general (Capitão-mor) , also resided in Lifau, at least for a time. Originally the area belonged to the empire of Ambeno , but the empire of Oecussi, which was ruled by Topasse, arose here under the toleration of the Timorese on the northeast coast of today's exclave. The mountainous west and south of the East Timorese Oe-Cusse Ambeno remained until the 20th century as the Empire of Ambeno under the leadership of local rulers, hence the common double name of the exclave. From Oecussi the Topasse made alliances with the former vassals Wehales by oaths of blood. The blood of the oath partners was mixed and drunk. As a token of the covenant, the Timorese rulers were given a flag of Portugal , a sword and pieces of armor, which, according to traditional beliefs, represented sacred symbols of Portugal's strength. By handing over to the Liurais, part of this strength should also pass to the local rulers. The sovereignty of the Portuguese crown was recognized, but this did not go hand in hand with the transfer of political or economic power. The Liurais remained the real rulers of their empires. But even if these empires were now nominally allies of the Portuguese, in reality the Topasse held all the strings of power together. In the 17th century there were never more than 50 Europeans in the Portuguese sphere of influence of Timor. The expansion and rule came from the black Portuguese .

In 1640 the Dutch built their first fortress on Timor near Kupang and the political division of the island began. The bay of Kupang was considered the best natural harbor of the island. From 1642 a simple fort again protected the Portuguese post. Two Dutch attacks failed because of him in 1644. For better defense, the Dominicans under António de São Jacinto built a new fortress in 1647. In 1653 the Dutch destroyed the Portuguese post, which was then re-established. In 1655 the ruler of Sonba'i, who had been allied with Portugal, rose up against the Portuguese. He killed all the Portuguese in his area and set fire to their houses and churches. Then Sonba'i allied itself with the Dutch, a loss for the Portuguese, because the empire was one of the most prestigious in the west of the island. The background to the rebellion seems to be the personal aversions of the Liurai von Sonba'i, described as aggressive, towards the Portuguese. In addition, the attack turned against the proselytizing of the animist residents. On January 27, 1656, the Dutch finally captured the Portuguese post in Kupang with a strong force under General Arnold de Vlamigh van Outshoorn. However, due to heavy losses, they had to withdraw from the fortress immediately after they had followed the Topasse outside Kupang. The Dutch suffered a bitter defeat in 1658 when the Portuguese and Topasse completely destroyed the kingdom of Sonba'i. Some residents of Sonba'i then settled with the Dutch in Kupang. When Liurais fell from the Portuguese, they sent allied Timorese warriors, such as those from Amarasi . Here the colonial power used the Timorese tradition of headhunting, which meant a constant state of war between different empires; a measure that was used until the 20th century. Like Sonba'i, other empires who rebelled against the Portuguese and Topasse, such as Taebenu , were particularly affected in 1658, 1683 and 1688 . Its inhabitants had to flee their homeland and moved to Kupang. The Dutch recruited new allies from them without much effort. By 1688 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) concluded treaties with the five small rulers in the area of Kupang, the "five loyal allies" in Sonbai Kecil , Kupang- Helong , Amabi (1665), Amfo'an (1683) and Taebenu (1688). In 1661 the VOC first signed an agreement with Portugal in which - in return for the Dutch post at Kupang - the company recognized Portuguese sovereignty over most of Timor. The Dutch sphere of influence was temporarily limited to this region of Timor, apart from Maubara , which allied itself with the Dutch in 1667. In 1688 the Dutch finally succeeded in conquering Kupang. The Atoni empires of Amanuban and Amarasi, which were allied with Portugal by the Topasse and were at constant war with the five loyal allies, initially stood in the way of further expansion.

In 1650, the Portuguese warned Christian Timorese not to trade with anyone other than themselves. Between 1665 and 1669, several empires were attacked by the Portuguese who had political or economic ties with the Dutch or Makassar merchants. In 1665 Wehale tried to win the Makassar traders as allies and further east they had a great influence in Ade (today Vemasse ) and Manatuto , which also set the Dutch flag, until 1668/69 . A fleet of the Topasse ended this alliance and conquered Ade and Manatuto, whereby they again belonged to Portuguese sovereignty. With the loss of Malacca in 1641 and Makassar in 1665, Macau became more and more important for the Portuguese on Timor as a connection to the outside world. Around 20 junks called the island annually and brought rice and barter goods. Chinese traders established trade relations with the Timorese in the pacified areas and also began to settle in Timor - first in Kupang and Lifau, and later also in Dili. They controlled much of the trade with Macau, including heavy smuggling. From the 1740s on, they traded directly with the Timorese, breaking the Topasse's trading power. For Macau, trade with Timor became the main source of income, especially since the lucrative trade with Japan had been lost in 1639. Until 1695, the Macau Senate issued trading licenses, known as pautas do navio . Then the hold of the ships was divided. One third was available to the shipowner, while two thirds were loaded for the benefit of various Macau citizens, from the captain general to widows and orphans. This system was seen as an advantage by shipowners and lasted for almost a hundred years.

In the late 17th century, several attempts by the Portuguese crown to gain control of all of Timor were foiled. In 1665 (1664?) The Portuguese commander Simão Luis was appointed the first Capitão-Mor of Solor and Timor, but the Larantuka-born died before the official inauguration. He was followed by António da Hornay , a captain of the Topasse, with which the title holder was practically equated with the ruler and commander-in-chief of the Topasse. The Topasse family clans of the Hornays (also Ornai , Horney ) and the Costas became the real rulers in the colony. The Portuguese took advantage of the rivalry between the two clans. The Portuguese viceroy in Goa had also sent the same letter to António da Hornay and Mateus da Costa in 1666, declaring them Capitão-Mor and his representative, provided that they were in power. At the time, this was with António, but Mateus did not accept this and relied on an earlier appointment. Between 1668 and 1670 Mateus da Costa subjugated several kingdoms of the Tetum in the coastal area of Belus for Portugal. From 1671 Mateus was also able to claim the title of Capitão-Mor for himself, but he died in 1673. After a brief interlude by Manuel da Costa Vieira, António da Hornay regained the title in the same year and ruled de facto as prince over Larantuka, Solor and parts of Timor. He is described by the Dutch as so ruthless that they hoped the Timorese would turn against him and the Portuguese because of it. Instead, the Dutch faced one of the few rebellions in their field at the time. In 1678, Raja Ama Besi of Kupang allied with the pro-Portuguese Amarasi to attack the successor to his throne. After the death of António da Hornay in 1693, he was replaced by Father António de Madre de Deus and finally by his brother Francisco da Hornay . Finally, the Hornays and the Costas were united through the marriage of Francisco da Hornay to a daughter of Domingos da Costa , the son of Mateus.

The Topasse were threatened from several quarters, once by Portuguese traders, who were given permission by the Crown to take control of the sandalwood trade, then by the Dominicans, who tried to build their own independent power base in Timor, and finally by local people Rulers who regularly rebelled against both the Topasse and the Portuguese. However, all were united by the struggle against the expansion of the Dutch. Most of the time, the Topasse succeeded in defeating rebellious rulers through repeated alliances. A VOC report from 1689 states:

“The Capitão-mor […] sometimes distributes some clothes and other things to important kings. If a rebellion breaks out here and there, he uses the soldiers in the war, together with other Timorese, because there are many kings on this island, each of whom has his own district. So he [the Capitão-mor] can use them more easily when these or others stand up to bring them back to their senses, without having to raise excessive costs. In addition, he shares the small and large booty with the above-mentioned warriors, so that all those who have followed his call to arms and taken against the rebels have a use. In this way they [the topasse] (if they are not attacked by an outside enemy) can keep the districts around here, and especially on the island of Timor, in strict loyalty without needing any help from the white Portuguese . "

Even if one called oneself “subject to the Portuguese king”, the Topasse ruled over the property, not Portugal. Portuguese officers in Timor received only a license from the Capitão-Mor to extract sandalwood and a small tribute that the local population had to pay. These tuthais consisted of rice, pigs and other natural products. European Portuguese made up a tiny minority in Timor anyway. The English traveler William Dampier observed in 1699:

“... although they value being called Portuguese and respect their religion, most of the men and all women who live here are Indians [Southeast Asians]; and there are very few real Portuguese on the whole island. But of those who call themselves Portuguese there are thousands; and I believe that they owe their strength more to their numbers than to good weapons or discipline. "

In 1695, the viceroy in Goa tried to regain control and was the first governor of Solor and Timor António de Mesquita Pimentel (1696-1697). But it quickly drew the anger of the locals. Pimentel shamelessly plundered them and murdered two of Francisco da Hornay's children. In 1697 Domingos da Costa became the new Capitão-Mor. He finally had Pimentel chained and sent back to Goa. Pimentel's successor André Coelho Vieira was captured by Domingos da Costa in Larantuka in 1698 and had to drive back to Macau. Only António Coelho Guerreiro (1702–1705), sent by the Viceroy in Goa in 1701 , was able to establish himself in Lifau with the support of Bishop Manuel de Santo António, even if the majority of the Topasse were hostile to him. Although Guerreiro ensured peace and order within Lifau, during his three-year tenure he was practically constantly besieged by the Costas. But Domingos da Costa was repeatedly threatened by various rivals.

|

|

|---|

| See List of Governors of Portuguese Timor |

On February 20, 1702, Guerreiro began his service in Lifau. The Dominicans were officially released from the administration of the property. Guerreiro built up a colonial administration and gave the Liurais the military rank of Coronel (colonel) - a tradition that was continued in Timor until the end of the Portuguese colonial era in 1975. Guerreiro held out until 1705 before he had to leave. After Manuel de Santo António (1705) Lourenço Lopes (1705-1706) took over the administration of the colony. He was followed by Manuel Ferreira de Almeida (1706-1708 and 1714-1715), who does not appear in the official list of governors and was probably a rival of Domingos da Costas. The Portuguese returned to Lifau, but their power remained limited. Manuel de Santo António ensured at Domingos da Costa that the new Portuguese governor Jácome de Morais Sarmento (1708-1710) was recognized again. But there was a dispute between Morais Sarmento and Manuel de Santo António. Morais Sarmento had Dom Mateus da Costa, the Liurai of Viqueque , arrested against all rights in 1708 and humiliated him. Manuel de Santo António himself had converted the ruler to Christianity, but Morais Sarmento felt that he was “too independent” and wanted to replace him. Domingos da Costa then besieged Lifau until 1709. Manuel de Santo António saved the situation by going to the camp of Domingos da Costa and persuading the Topasse ruler to put himself back under the Portuguese crown. The subsequent governor Manuel de Souto-Maior (1710-1714) rehabilitated Dom Mateus, but the alliance between the clergy and the civil administration was destroyed. The topasse continued to dominate the sandalwood trade in the interior of the island. Sometimes the Portuguese and the Dutch worked together to bring Topasse and Timorese back under control.

Topasse rule collapses and the Portuguese are driven to Dili

After another interlude by Manuel Ferreira de Almeida, which ended fatally, Domingos da Costa (1715-1718) had control of the colony himself until it was again taken over by the new governor from Portugal Francisco de Melo e Castro (1718-1719) has been. In 1719 the Liurais of a dozen or so rich met in Camenaça to make a blood pact. The aim of the federal government was to expel the Portuguese and Christianity as a whole. The Camenaça Pact (Camnace Pact) is considered to be the beginning of the Cailaco Rebellion (1719–1769). Governor Melo e Castro had to flee and Bishop Manuel de Santo António took over the official duties (1719-1722). But there was also an open conflict between Manuel de Santo António and the Topasse. In 1722 the bishop sent Arraias , as Timorese auxiliary troops were called, from Amakono (Groß-Sonba'i) against the Topasse. The amakono were slaughtered. At the same time, other Arrais fought against rebels in Belu. Luca warriors attacked a squad of Moradores who were collecting the Fintas and were on their way from Lifau to Cailaco . Fintas were tribute payments from the kingdoms allied with Portugal in the form of natural produce, as was common between the Timorese rulers. The trigger was less the obligation to pay, which was introduced between 1710 and 1714, than the violence with which the taxes were collected. Only Governor António Moniz de Macedo (1725–1728 and 1734–1741) was supposed to set a regulation in writing for the first time on July 10, 1737 about the collection of Fintas. Until then, the levies were levied quite arbitrarily and in some cases the income did not even cover the costs of collection. The idea of a poll tax was initially abandoned and only taken up and implemented again at the beginning of the 20th century.

1722 met the new Portuguese governor António de Albuquerque Coelho (1722-1725) in Lifau. This exiled bishop Manuel de Santo António, who was considered a difficult character, from Timor. He was not to return to the island until his death in 1733. The banishment of Manuel de Santo António created problems because many Timorese allies had little interest in fighting for a governor who had sent their venerable bishop away. Albuquerque Coelho was besieged for three years by the Topasse under Francisco da Hornay II in Lifau, as was his successor Macedo for a long time. Even later, the bishops of Malacca repeatedly resided in Lifau. In 1739, Bishop António de Castro came to Timor and founded the first seminary here in 1742. In 1743 he died at the age of 36 due to the climate. His remains were interred in Lifau. In 1749 Bishop Geraldo de São José came to Lifau. He is said to have died under mysterious circumstances in 1760.

Long decision-making processes were a major problem for the administration of the colony. In 1723 traders from Macau complained to the Viceroy in Goa that taxes that Albuquerque Coelho had introduced on the sandalwood trade would make the trip to the islands unprofitable. The complaint was forwarded to the king in Portugal, who only referred it to the Council of Ministers in the Overseas Ministry for examination in August 1725, through his State Secretary. After the latter assessed the taxes as excessive, the viceroy in Goa was finally instructed on March 23, 1726 to abolish the taxes.

In 1725 the rebellion broke out with all its might when the Liurai of Lolotoe refused to pay his fintas and the Portuguese collectors found it difficult to flee to Batugade. Under the leadership of Camenaça, churches were destroyed and missionaries and converted Timorese were murdered. The newly arrived Macedo first tried to negotiate with the rebels, but then sent troops to Cailaco, which was considered the rebel headquarters. The Pedras de Cailaco (Rock of Cailaco), the steep cliffs of Mount Leolaco ( 1929 m ), offered the empire a natural fortress and were considered impregnable. The Portuguese besieged Cailaco for over 40 days from October 23 to December 8, 1726, but then had to give up, also due to heavy rainfall. On January 13, 1727, some rebel leaders gave in and signed a new alliance with the Portuguese. In 1730, Governor Pedro de Melo (1728–1731) moved to Manatuto and had to repel an attack by 15,000 warriors there. After 85 days he managed to break the siege. Although he was unable to drive the rebels out of this region, he made alliances with the Liurai of Manatuto and other local rulers - a circumstance that should facilitate the later relocation of the colonial capital from Lifau to Dili. On his return Melo found that Topasse and Timorese were again besieging Lifau. Only the timely arrival of Melo's successor Pedro de Rego Barreto da Gama e Castro (1731-1734) prevented the Portuguese from having to give up Lifau. Gama e Castro managed to make peace with Camenaça and others by 1732, but new rebellions kept breaking out. When António Moniz de Macedo took up his second term in 1734, he was greeted surprisingly friendly by the Topasse leader and Capitão-Mor Gaspar da Costa . Another alliance between the Portuguese and Topasse came about in 1737.

The Topasse tried three times to drive the Dutch from Timor: 1735, 1745, 1749. In 1748 Amfo'an attacked the Topasse, whereupon they devastated Amanuban and Amakono. Both then moved to the VOC warehouse. Amakonos ruler fled with his men to Kupang, which is considered to be one of the triggers for the joint attack by the Portuguese and Topasse on October 18, 1749 on Kupang. This ended in disaster despite the overwhelming power. The Dutch had called on their Timorese allies and Marjdikers of Solor, Roti and Semau for help. The Marjdikers were a mixed population of different "Indian peoples" who, unlike the Topasse, did not admit to the Catholic faith . They established themselves in inter-island trade and supported the Dutch. At the battle of Penfui (now where Kupang's airport is located ) on November 9, 1749, a last attempt to drive the Dutch out of Kupang failed. A force of 50,000 men led by Gaspar da Costa did not succeed in defeating the 23 European soldiers and several hundred local defenders. Gaspar da Costa and many other Topasse leaders were killed. A total of 40,000 warriors of the Topasse and their allies are said to have perished. Other literature sources speak of only 2,000 deaths. As a result of the defeat, the rule of the Portuguese and Topasse in West Timor collapsed. Even Amarasi, one of the Portuguese 'most loyal allies, switched sides. In April 1751 Liurais rose again from Servião ; According to a source, Gaspar is said to have died here.

In the years that followed, the Dutch's new allies wavered again. Topasse and Portuguese were able to move the empires of Amarasi and Amakono back to an alliance with great promises. According to Dutch sources, Catholic priests worked with "the most beautiful promises" and "the darkest threats".

In March 1752, the Dutch commander of Kupang, the German Hans Albrecht von Plüskow , attacked the empire of Amakono and shortly afterwards also Amarasi and the Topasse empire of Noimuti . The Emperor of Amakono was exiled to Batavia. The Liurai of Amarasi, surrounded by enemies, had themselves and all women and children killed by their own people. Over a hundred people died. In Noimuti Plüskow took 400 prisoners and captured 14 cannons.

At the instigation of the VOC diplomat Johannes Andreas Paravicini , 48 rulers of Solors, Rotis, Sawus , Sumbas and a large part of West Timor concluded alliances with the Dutch East India Company in 1756. This was the beginning of Dutch rule in what is now Indonesian West Timor. Among the signatories was a certain Jacinto Correa (Hiacijinto Corea) , "King of Wewiku-Wehale" and "Grand Duke of Belu", who also signed the dubious Treaty of Paravicini on behalf of 27 empires under his control in central Timor . Fortunately for the Portuguese, Wehale was no longer powerful enough to pull all local rulers to the side of the Dutch. So 16 of the 27 former vassals of Wehales in the east remained under the flag of Portugal, while Wehale itself fell under Dutch rule. However, the Dutch did not really enjoy their land gain, as they still had little access to the lucrative sandalwood. They never succeeded in making profits comparable to those of the Portuguese or Chinese in the sandalwood trade.

When Francisco da Hornay III. took over the management of the Topasse from his late father João da Hornay in 1757, there was a dispute with the Costas over the claim. The dispute ended with the marriage of Francisco with the sister of Domingos da Costa II and the appointment of Domingo as lieutenant general. António da Costa, Domingos' younger brother, became ruler of Noimuti. Larantuka was controlled by Dona Maria, João's sister. The Dutch took the opportunity. They persuaded Maria to marry an attractive Dutch official and thus brought Larantuka into the sphere of influence of the VOC.

In 1759, the governor Vicento Ferreira de Carvalho (1756-1759) decided to give up and sell Lifau to the Dutch. When the Dutch wanted to take possession of the place under Hans Albrecht von Plüskow in 1760, they were faced with a Topasse force. From Plüskow was from Francisco da Hornay III. and António da Costa murdered. The extent to which the new Portuguese governor Sebastião de Azevedo e Brito (1759–1760) was involved in the defense is contradictory in the sources. The relationship between the governor and Dominicans had deteriorated significantly by this time. Finally, the Dominican Jacinto da Conceição had the governor Azevedo e Brito arrested and deported him to Goa. Brother Jacinto da Conceição took over the administration of the colony (1760–1761) together with a councilor (Conselho Governativo) with Vicente Ferreira de Carvalho and Dom José, the Liurai of Alas . But Jacinto da Conceição was murdered by a co-conspirator. From 1762 the government council of brother Francisco de Purificação and Francisco da Hornay III. guided. 1763 the new governor Dionísio Gonçalves Rebelo Galvão arrived on Timor, but he died on November 28, 1765. He was by Francisco da Hornay III. poisoned. Again the Dominicans took over the administration of the colony , this time under António de São Boaventura with José Rodrigues Pereira. Since Francisco da Hornay III. was excluded from power, he besieged Lifau from 1766. With his relative António da Hornay II, Francisco made an alliance and ended the temporary division of the Topasse with the aim of driving the Portuguese from Timor for good.

In 1768, the new Portuguese governor António José Teles de Meneses (1768–1776) landed in Lifau with a battalion that was recruited in Sikka. But even this reinforcement did not bring about a turning point. In view of the ongoing siege, Teles de Meneses finally gave up Lifau on August 11, 1769 and left Lifau on ships with 1,200 people heading east. On October 10th, the governor began expanding Dilis into the new administrative center. Shortly afterwards, 42 Liurais swore allegiance to Portugal, including the influential Dom Felipe de Freitas Soares, ruler of Vemasse , and Dom Alexandre, ruler of Motael , who contractually transferred the entire plain from Dili to the surrounding mountains to Portugal. Due to the previous contacts of the Dominicans with the Timorese rulers, with missions in Manatuto and Viqueque already being founded, Portugal was able to rely on a relatively large amount of support from the Liurais at this time. This was later no longer the case. Francisco da Hornay offered Lifau to the Dutch, but they refused after careful consideration.

The struggle for the ultimate limit

When Dilis was founded, there was a balance of strength between the Portuguese, Dutch and Topasse in Timor. Portugal ruled the north coast of Timor from Batugade to Lautém , with the exception of Maubara, where the Dutch had built a fort in 1756 . Portuguese rule relied on native allies. South of Dili there were Motael, Dailor , Atsabe and Maubisse . To the west, the kingdoms of Ermera , Liquiçá and Leamean supported the Portuguese. In the east they found allies in Hera and Vemasse. The border with West Timor was secured by the empires of Servião , Cowa and Balibo, and in the southeast, across the mountain range, the empires of Samoro , Lacluta and Viqueque were allies of Portugal at that time . However, there were gaps in the alliance system on the south coast and in the east. Basically Timor was now divided into a sphere of influence of the Dutch in the west, with the exception of the Topasse area, and a Portuguese sphere of influence in the east.

The sandalwood deposits on the island had already decreased significantly by 1710 due to excessive deforestation. The Cailaco rebellion and the entry of Chinese traders from Canton into trade between China, Timor and Batavia in 1723 made trade from Macau unprofitable. And the Dutch East India Company also decided in 1752, faced with significant losses, to give up its monopoly on the sandalwood trade and to allow anyone against a commission to cut sandalwood. The result was that the sandalwood trade finally fell under the control of Chinese traders. Only one or two schooners a year came to Kupang from Batavia and brought various materials which they exchanged for wax, turtle shells, some sandalwood and beans. According to a French report from 1782, the profit was just enough to cover the costs. Governor João Baptista Vieira Godinho (1785-1788) tried to break the Chinese monopoly by advocating free trade between Timor and Goa. In 1785 Dili had, at least nominally, sovereignty over the trade tariffs in Portuguese Timor. This was important because the salaries of the governor and officials were paid for by them - a circumstance that would later lead to payment difficulties. Several customs stations were built on the north coast, which also documented the Portuguese claim to ownership. As a result of the trade facilitation, more Portuguese and Armenian families also settled here .

In 1779, Governor Caetano de Lemos Telo de Meneses (1776 to 1779) was exiled to Mozambique . He was accused of causing the fire in the Dili archives through criminal negligence, which destroyed much of the colony's records. In addition, there were massive complaints about the administration, for example by the Bishop of Macau, who complained in a letter in 1777 about the scandalous behavior of the governor. In 1777 (according to other sources 1776, 1779 or 1781) the empire of Luca rose up due to repression against the animistic religion in a revolt against the Portuguese colonial rulers that lasted until 1785, the " war of the mad " ( Portuguese guerra de loucos , also called guerra dos doidos ). A "prophetess" had announced to the warriors that the ancestors would support them to shake off the yoke of the strangers. The warriors considered themselves invulnerable. Viqueque supported the Portuguese in suppressing the rebellion. Similar groups who try to protect themselves with magical rituals in battle can still be found in East Timor today. The rebellion was successfully put down by Governor Godinho. Lifau was also able to persuade Godinho to return to Portuguese rule in 1785. On Solor he guaranteed the Topasse leader Pedro da Hornay his title and status as lieutenant general ( tenente general ), as did his nephew Dom Constantino do Rosario , the king of Solor. Dom Constantino then guaranteed his loyalty to Portugal and offered assistance in the defense of Dilis. Pedro da Hornay took military action against the Dutch due to the alliance with Godinho, but this was not approved by the Viceroy of Goa at the time. Godinho, widely regarded as a capable governor, was dismissed early. A step that Goa later regretted. His successor, Governor Feliciano António Nogueira Lisboa (1788 to 1790) soon got into a dispute with the representative of the Catholic Church in Manatuto, the monk Francisco Luis da Cunha . Both accused each other of robbery and the theft of customs revenue, among other things. To get rid of the governor, the monk incited the people of Manatuto to rebellion. Christianized Timorese threatened to spread the revolt to all of Belu. Finally, the Viceroy of Goa took action, had both men arrested and deported from Timor. The new governor Joaquim Xavier de Morais Sarmento (1790 to 1794) brought the situation back under control. In the meantime, the Topasse ruler Pedro da Hornay attacked Maubara unsuccessfully on behalf of Portugal in 1790, with which he only managed to get the empire west of Dili to renew its alliance with the Netherlands and to set the flag of the Netherlands as a symbol . The Dutch also struggled with rebellions in the 1750s and 1780s. Worst of all was the renewed loss of Great Sonba'i, which now moved as an independent empire between the Dutch and the Portuguese.

By 1800 Portugal had about 40 military posts along the coast and a military camp with 2,000 local soldiers, who were commanded by Portuguese officers. Some of these were also Indian sepoys . Most of the 50 to 60 officers lived in Dili, but some were also stationed in the outposts. First and foremost, they were intended to prevent Dutch ambitions in East Timor, but for a long time the fortifications of Dilis were inadequate and the cannons were mostly in poor condition. A company of Moradores was stationed in Manatuto to secure Portugal's influence in the important center of the domain. Due to the chronic staff shortage, even deportees from Goa were used for the lower ranks in the administration . But Timorese came to Goa unintentionally during this time. Dom Felipe de Freitas , the illegitimate son of the Liurais of Vemasse, was exiled to Goa in 1803 by Governor João Vicente Soares da Veiga (1803 to 1807) as the first Timorese rebel . Until then, this punishment had not been common. A revolt broke out in Venilale in 1807 when the Liurai Cristóvão Guterres was unjustly arrested. Only in Goa was he acquitted by a court. After the death of Governor António Botelho Homem Bernardes Pessoa , in his first year in office, the post of governor was vacant from 1810 to 1812 and a Conselho Governativo led the fortunes of the colony. Power was in the hands of Dom Gregório Rodrigues Pereira , the Liurai of Motael , Lieutenant Colonel ( tenente-coronel ) Joaquim António Veloso and José de Anunciação , the bishop who was residing in Manatuto at the time . The new governor Vitorino Freire da Cunha Gusmão (1812 to 1815) first had to assert himself against these parties . In the meantime Lacluta, Maubara and Cailaco rebelled against the tribute payments in 1811.

Great Britain occupied the Dutch possessions on Timor between 1811 and 1816 in order to prevent French attempts to establish themselves here during the Napoleonic Wars . Indeed, at the end of the 18th century there were already considerations in France to acquire territories in the region, but in the end these efforts were never pushed beyond a few research expeditions. After the return of the Orange to the Dutch throne, the Dutch received their Timorese possessions back on October 7, 1816. Portugal, allied with the British, took the opportunity to renew its claims to the river port of Atapupu , between Oe-Cusse Ambeno and Batugade, and took control in 1812. Atapupu became a major source of customs revenue for the Portuguese colony.

In 1814, several Portuguese possessions on the Lesser Sunda Islands were administered from Dili. In addition to Portuguese Timor, these were the realms of Sikka , Larantuka and Noumba on Flores, Solor, the two realms of Alor, Lembata (Lomblen) , Pantar , Adonara and a few other smaller possessions. Governor José Pinto Alcoforado de Azevedo e Sousa (1815 to 1820) had to put down a rebellion in Batugade. He was just as unable to prevent the Dutch from occupying the island of Pantar as the occupation of Atapupus on April 20, 1818 by 30 Dutch soldiers who, on behalf of Hazaert , their commander in West Timor, took possession of the river port and the Portuguese flag replaced by the flag of the Netherlands . Behind the occupation were the ambitions of Chinese traders from Kupang who wanted to save the tariffs demanded by Portugal in this way. Atapupu was an important port for smaller ships and a major source of customs revenue for the Portuguese. Governor Alcoforado de Azevedo e Sousa complained in Batavia about Hazaert's arbitrary occupation, his efforts to conquer Batugade and to stir up the local rulers and the Chinese traders against the Portuguese. Alcoforado de Azevedo e Sousa threatened to take troops against the Dutch in Timor and demanded financial compensation. However, the commission found that the Portuguese had incorrectly stated the facts and rehabilitated Hazaert, who returned to his office in Kupang in 1820. It is believed that Portugal retaliated for the loss by providing men and arms to the rebellious ruler of Amanuban in West Timor.

In 1832 the long-time governor Manuel Joaquim de Matos Góis (1821 to 1832) died in Dili. A Conselho Governativo took over the administration, to which Francisco Inácio de Seabra , brother Vicente Ferreira Varela and José Pereira de Azevedo belonged. In the same year the new governor Miguel da Silveira Lorena arrived in the colony, but he too died shortly after his arrival. Again the Conselho Governativo took over , but a dispute broke out. Vicente Ferreira Varela had the other two members of the council arrested and now ran the business alone until the new governor José Maria Marques (1834 to 1839) arrived in Dili.

In 1838 the British founded the settlement of Port Essington in what is now the Australian Northern Territory . The settlers faced many difficulties. After they had previously supplied themselves with food from the Dutch colony on Kisar , in early 1839 they brought water buffalo, Timor ponies and some English newspapers from Dili to Port Essington. On February 13, the British commander Sir James J. Gordon Bremer visited Dili and secured further help from the local governor Frederico Leão Cabreira (1839 to 1844) for the new settlement due to the old alliance between the two colonial powers. Even if Port Essington was given up again by the British in 1849, the renewal of the alliance with the British meant additional support for Portugal against the expansion pressure from the Dutch in this region.

On September 20, 1844, Macau, along with Portuguese Timor and Solor, was separated from Goa as a separate general government. In the same year, the Portuguese ports of Timor were declared free ports, which means that ships from other nations were now allowed to dock in the ports to trade. Dili benefited from the import and export duties. In 1846 the Netherlands began talks with Portugal about taking over Portuguese territories, but Portugal initially turned down any offer. In 1847 there was a dispute over the belonging of the islands of Pantar and Alor. The Liurai von Oecussi from the Hornay clan claimed it as part of his dominion, which thus fell under Portuguese suzerainty. The Dutch from Kupang, in turn, claimed the two islands. Governor Julião José da Silva Vieira (1844 to 1848) rejected this and supported the Liurai in his claim. Both sides strengthened their troops on Timor, but it was clear that Portugal was losing out here, both financially and in terms of strength. In 1850 the Netherlands proposed again negotiations on the demarcation of the boundary on the Lesser Sunda Islands.

But the military weakness of the Portuguese was also evident in protecting the colony from external threats. In 1847, for example, Buginese pirates or slave hunters probably attacked a place in what is now Lautém , which was not unusual at that time. Governor Silva Vieira sent a military expedition, but it was defeated by the pirates. Three soldiers were killed in the process. For another four and a half months, the 70 Buginese managed to defend themselves against a siege by 3000 warriors who had drawn the local rulers together.

The subsequent governor António Olavo Monteiro Tôrres (1848 to 1851) faced an uprising by an apostate Moradores in Ermera with only 120 (mostly Timorese) soldiers. 6000 warriors devastated Ermera and killed the local Liurai and 60 of his followers. Governor Tôrres was forced to seek help from the Liurai of Oecussi, who then attacked the rebel empire of Balibo. On this occasion, they raised the Portuguese flag in Janilo ( Djenilo ), which in turn attracted the Dutch, who feared that the port of Atapupu would lose its connection with the interior. Negotiations to settle the border disputes led by José Joaquim Lopes de Lima on the Portuguese side were unsuccessful. At the same time rulers of Pantar and Alor complained that Oecussi's rulers would intervene in internal conflicts on the neighboring islands and claim them for Portugal. Tôrres revoked the claims.

On October 30, 1850, the Portuguese possessions on the Lesser Sunda Islands received the status of an autonomous province that was directly subordinate to Lisbon. The reason for this is said to have been the appointment of José Joaquim Lopes de Lima (1851 to 1852) as governor of the colony, who arrived in Dili on June 23, 1851. He was previously the provisional governor general of Goa (Governador Geral Interino) , an appointment as simple district governor (Governador Subalterno) would have been equivalent to demotion. Another reason was the distance to Macau, which made quick decisions impossible. The colony was placed under the direct control of the central government, a government and finance council was founded in Dili and two Timorese were accepted into the colonial government.

Lopes de Lima sent a punitive expedition against the empire of Sarau , which was suspected of collaborating with the Buginese pirates. The retaliatory action over eight months, in which the gunboat Mondego was also used, ultimately brought in compensation of 2,000 rupees. The heads of the fallen opponents were brought back to Dili and displayed at the Likurai dance. The Timorese practice was repeatedly used by the Portuguese to deter rebellions in the following years.

In 1851 the Dutch and Portuguese sent a commission to clarify the property disputes. In July Lopes de Lima reached an agreement with Baron von Lynden , the Dutch governor of Kupang, in Dili on the colonial borders in the region, but without authorization from Lisbon. In it, the Portuguese claims to most of West Timor were finally given up in favor of the Dutch, for which the Dutch exclave Maubara in the east should go to Portugal. Solor, Pantar, Alor and the eastern part of Flores that remained in Portugal were sold to the Dutch. The reason for Lopes de Lima's arbitrary decision was the bankruptcy of the Portuguese colony. The officials had not received a wage for two years, the warship Mondego was in need of repair and Lopes de Lima wanted to buy some schooners to get the trade going again. Therefore, he also requested an immediate payment of a first installment of 80,000 florins of the 200,000 florins total. Lopes de Lima must also be credited with the fact that the properties on Flores were more of a losing proposition and that economic relations with the other islands only existed vaguely.

As might be expected, the Portuguese governor fell out of favor when Lisbon learned of the treaty, even if the territories sold were more of a burden than a gain for the Portuguese colonial empire. On September 8, 1852 Lopes de Lima's successor Manuel de Saldanha da Gama (1852 to 1856) arrived on board the Mondego in Dili, had his predecessor arrested and sent him back to Lisbon. Lopes de Lima died of a fever on the return journey in Batavia.

On September 15, 1851, the colony was returned to Macau's sovereignty, but the agreements with the Dutch could not be reversed, even if the treaty on the borders was renegotiated from 1854 and only finally signed as the Treaty of Lisbon in 1859 . The various small kingdoms of Timor were divided under Dutch and Portuguese authority. The Dutch ceded Maubara to the Portuguese (April 1861) and recognized their claims to Oecussi and Noimuti. In return, the Portuguese accepted the Dutch sovereignty over Maucatar and Lamaknen . This meant that the treaty had some weak points. With Maucatar and Noimuti, an enclave without sea access each remained in the territory of the other side. In addition, the imprecise borders of the Timorese empires and their traditional claims formed the basis for the colonial demarcation.