Kemak

The Kemak ( Ema , Port .: Quémaque ) are an ethnic group with over 69,000 members in the north of Central Timor .

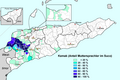

Settlement area

For the most part, the Kemak live in the East Timorese administrative offices of Atabae , Cailaco , Maliana ( municipality of Bobonaro , 39,000 Kemak) and Atsabe (municipality of Ermera , 18,500 Kemak), but partly also in the municipality of Cova Lima (2,100) and in the Indonesian administrative district ( Kabupaten ) Belu . According to the 2015 census, 68,995 East Timorese speak Kemak as their mother tongue. In 1970 there were 45,084.

history

Atsabe-Kemak

Atsabe was one of the centers of Timor under the Koronel messenger of Atsabe-Kemak even before the colonial era, which dominated all of the areas in East Timor inhabited by Kemak until the colonial era. The Kemak areas in the north of today's Bobonaro , in the northern Ainaro and in the area of Suai were tributary to Atsabe. The small Kemak empire of Marobo had a peripheral location, which is why the Kemak mixed with the neighboring Bunak there for generations . Atsabe was part of the complex alliance system of rituals, marriage and trade that the Tetum Empire of Wehale had linked with its capital, Laran . Laran was also the spiritual center of the entire island. In addition to Tetum and Kemak, Bunak and the Mambai of Aileu were also part of this alliance system. Together with the east of the island, the Portuguese called this area Belu (also Belos or Behale).

According to oral tradition, the Atsabe-Kemak came under Portuguese colonial rule relatively late . One reason could have been the far-reaching dispersal of the inhabitants and the impassability of the mountainous landscape. It was not until the 19th century that Portuguese - Angolan troops are said to have penetrated the area for the first time. The then Koronel messenger Dom Tomas resisted the invaders. Dom Tomas was defeated, however, and had to flee to Atambua in west Timor. Portuguese sources do not actually mention the region of Atsabe and a Liurai there until the middle of the 19th century. The Atsabe rulers had a reputation for being particularly inclined to rebel against the colonial rulers and their presence. Two of Dom Toma's grandchildren, Nai Resi and Nai Sama later fought for power. While Nai Resi turned against the Portuguese colonial rulers, Nai Sama supported the Portuguese. Nai Sama was eventually executed by his own men, while Nai Resi was captured by the Portuguese in Hatulia and also executed.

The Portuguese were initially seen as another people with their own coronel messenger . After the resistance against them failed, the Kemak accepted the leaders of the Portuguese in their hierarchy as higher up with a larger army and holy men, the Catholic priests, with a larger luli . The flag of the Portuguese and even the flagpole were considered sacred objects . The coronel messengers confirmed as administrators of Portugal were legitimized again by handing over the flag.

The Kemak's acceptance of introduced Catholicism was closely related to their understanding of holiness personified. The imported holiness was seen as a stronger extension of the local, traditionally existing luli . The Catholic priests were given land to build chapels and missionary work was allowed. Less because of friendliness or because of successful conversion than from the calculation of being able to increase one's own spiritual powers.

Nai Resi's son Dom Siprianu became Atsabe's coronel messenger in 1912 . During the Japanese occupation of Timor , he and the people of Atsabe offered passive resistance. Siprianu was therefore taken hostage by the Japanese along with six relatives and later executed.

Since the Portuguese education system was reserved for the ruling class, it was also able to secure the leading posts in the colonial administration. The same was true later during the Indonesian occupation, whereby the boundaries between collaboration and apparent cooperation for the protection of the own population were fluid. The East Timorese resistance also found partial support here.

The son of Siprianu and the last coronel messenger from Atsabe, Dom Guilherme Maria Gonçalves , was a co-founder of the pro-Indonesian party APODETI in 1974 , which called for East Timor to join Indonesia. During the Indonesian occupation, Dom Guilherme was the Indonesian governor of Timor Timur between 1978 and 1982 . He later distanced himself from Indonesia and went into exile in Portugal. After the people of East Timor voted for independence from Indonesia in a 1999 referendum, pro-Indonesian militias attacked family members and allies of the Koronel offer . The reasons are presumed to be the support of the independence movement by the Coronel messenger , but also envy of the family's economic prosperity.

Other Kemak groups

In the spring of 1867, the Kemak from Lermean (today the municipality of Ermera) , who were under the sovereignty of Maubara, rose against the Portuguese colonial rulers. Governor Francisco Teixeira da Silva put down the resistance in an unequal battle. In the decisive battle, which lasted 48 hours, the rebels had to defend themselves against a superior force that was superior to firepower. 15 villages were captured and burned down. The number of victims among the Timorese is not known, the Portuguese put their own casualties at two dead and eight wounded. The territory of Lermeans was divided among the neighboring kingdoms.

In 1868 the Portuguese sent a force to Sanirin (Sanir, Saniry) in the Batugade military command , whose Liurai refused to pay taxes. The Kemak of Sanirin were officially tributaries to Balibo .

Between 1894 and 1897, several empires rebelled in the west of the Portuguese colony. Several Kemak empires, such as Sanirin , Cotubaba and Deribate, were practically wiped out in the Portuguese punishment . Thousands of residents fled to West Timor in the Netherlands and settled there in Belu. More followed in the years between 1900 and 1912. Studies assume at least 12,000 refugees.

Religion and social structure

Like the other ethnic groups of East Timor, the Kemak are today largely followers of the Catholic faith. Almost all residents of the Atsabe administrative office are Catholics. It spread particularly during the Indonesian occupation (1975-1999) as a demarcation from the predominantly Muslim invaders. The church offered protection, criticized the brutal actions of the occupiers and represented a means of peaceful protest. The devotion to Mary is particularly pronounced , which is particularly evident in small towns through a large number of statues of Mary in churches and grottos.

Nevertheless, traces of the animistic , traditional religion can still be found in Christian rites today. Components of the old religion are ancestor cult , relic worship and the concept of holy (kemak: luli , tetum : lulik ) places. One of them is Mount Dar Lau , which is considered the mythical place of origin of the Atsabe- Kemak . According to the legend, earth and heaven were connected to one another at this point. Christian priests, like animist priests before, are venerated as holy men with spiritual powers ( luli ). These powers are passed on through the blessing. These forces are not only derived from office. Rather, men who are said to have spiritual powers take over the priesthood.

There are slight variations in the ceremonies between the various Kemak groups, such as the Atsabe Kemak and the Marobo Kemak .

Society is characterized by a hierarchical division into families and houses . The house of the Koronel messenger (Tetum: Liurai ), the traditional king, drew its authority from its origins from the founding fathers and their luli . The latter could reside in a person as well as in sacred objects. The same applies to the traditional priests ( Gase ubu ), who claimed their position based on their origins and ritual knowledge. They were the keepers of sacred history and lore. Only the king surpassed her in holiness. He preserved most of the sacred objects that descended from the founding fathers. But the authority of the priests was limited to the ritual. It was possible, however, for a person to have both worldly power, for example as a village chief, and be a priest at the same time. The king of Atsabe held both authorities. In addition, the house of the king secured its position of power through a strategic marriage policy , the exchange of women and material goods and the formation of an army to fight in regional feuds and for headhunting .

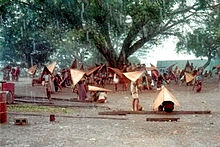

The holy houses are built together by all men belonging to a lineage. To do this, they meet on a weekend, once a month, for eleven months. At the end of the monthly work, there is always a small, ritual festival. The holy houses consist of seven levels, each of which has four steps. Access is restricted depending on the degree of kinship to the line. Simple guests are only allowed to go to the lowest level of the house, friends at least to the second level, relatives by marriage to the third, relatives from neighboring villages to the fourth and sometimes to the fifth, those who are married to the village are allowed to the sixth and only the Lulik Nain ( German Lord of the Holy ) to the seventh level. He is the keeper of the house and the sacred objects that are kept here. When the house is inaugurated, a buffalo is sacrificed and a great festival is celebrated.

The Kemak funeral ceremonies

The Kemak ( Tau tana mate ) burial ceremonies are divided into three phases: Huku bou , Leko-cicir lia and Koli nughu . The funeral ceremonies are called black rituals ( Metama no ). It is one of the occasions on which the living come into contact with their ancestors, which also leads to the renewal and restructuring of social ties between the living and the dead and between allies linked by marriage. The house of the “bride-giver” ( ai mea ) and that of the “bride-acceptor” play central roles in burial ceremonies, just as they do in other major events. The ritual cannot begin until all relatives have arrived. The blood of the sacrificial animals donated by the Ai mea is used to paint ritual objects and the grave. In the times of polygamy, the presence of second wives and their houses (by -by ) was an absolute duty. In addition there are the entire sidelines, such as those houses of the older and younger ( ka'ara-aliri ), those connected by marriage, and friends and allies.

With the Atsabe Kemak , the first phase of burial, the huku bou , consists of the sacrifice of at least five water buffalo and several goats and pigs . The deceased is then buried in a Christian grave. The second phase, the Leko-cicir lia , is the most expensive ritual of the Kemak culture. This is usually done together for several deceased. Only the dead in high positions, such as a coronel messenger , receive a separate ritual. The ritual is usually performed before the start of the planting season (August to September), as it is connected with the request to the ancestors for a rich harvest. According to traditional beliefs, without the second rite, the soul of the deceased remains near his home and village (Asi naba coa pu) . The later the Leko-cicir lia takes place, the more the lonely soul should long for company and therefore call for the souls of the living. An accumulation of deaths within a house is considered a sign of such an event. Nevertheless, the ritual is usually only performed years after the first phase, as the house of the dead must first restore the economic conditions for the expensive ritual. It is particularly complex due to the concept of the second burial . The bones of the deceased are dug up, cleaned and reburied, while the soul of the dead is led through ritual chants ( nele ) of the priest to the village of the ancestors on Tatamailau , East Timor's highest mountain. The chants can last up to 14 hours. During the ritual, mainly water buffalo are again offered as animal sacrifices. At the end of the ceremony, the severed sexual organs of all sacrificial animals are brought deep into the sacred grove (Ai lara hui) and deposited there in front of Bia Mata Ai Pun (the origin of spring and the trees). The ancestors are conjured up by a song, through animal sacrifices to transfer the souls of the dead to the ancestors. At the end, the dead man's bones are buried again. Nowadays, the conclusion is a Christian mass, the only reference to the new faith.

Web links

- Joanna Barrkman: Reaffirming the Kemak Culture of Marobo then and now ( Memento December 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Timor Aid, 2013.

supporting documents

- Andrea K. Molnar: Died in the service of Portugal : Legitimacy of authority and dynamics of group identity among the Atsabe Kemak in East Timor, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore. 2005.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Direcção-Geral de Estatística : Results of the 2015 census , accessed on November 23, 2016.

- ^ Brigitte Renard-Clamagirand: Marobo, Une Sociiti Ema de Timor Central. Priface de G. Condominas Ase12 (Langues Et Civilizations de L'Asie Du Sud-Est Et Du Monde In) , 1982, ISBN 9782852971233 (French)

- ↑ Statistical Office of East Timor, results of the 2010 census of the individual sucos ( Memento of January 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Geoffrey C. Gunn: History of Timor , p. 86. ( Memento of the original of March 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - Lisbon Technical University (PDF file; 805 kB)

- ↑ Andrey Damaledo: Divided Loyalties: Displacement, belonging and citizenship among East Timorese in West Timor , ANU press, 2018, limited preview in Google Book Search

- ↑ Matthew Libbis BA (Hons) Anthropology: Rituals, Sacrifice & Symbolism in Timor-Leste , accessed February 18, 2015.

- ^ Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University - East Timor People and Culture