Bunak

The Bunak (Bunaq, Buna ', Bunake, Búnaque, Búnaque, Mgai, Gaiq, Gaeq, Gai, Marae) are an ethno-linguistic group with around 100,000 members in the mountainous region of Central Timors , on the border between West and East Timor . Its core area is in the East Timorese communities of Bobonaro and Cova Lima . From here they expanded into the surrounding regions, where they sometimes live in close proximity to other ethnic groups. Some Bunak settlements were only founded a few decades ago due to the eventful history of East Timor . The Bunak are one of four ethnic groups in Timor that speak Papuan languages, while the majority of Timorese speak Malayo-Polynesian languages . The Bunak were therefore heavily influenced both linguistically and culturally by their Austronesian neighbors .

Settlement area

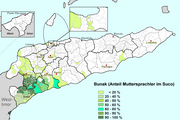

The current settlement area of the Bunak is in the mountains of Central Timor and ranges from the East Timorese city of Maliana in the north to the Timor Sea in the south, where Bunak and Tetum communities often coexist next to each other. There is a linguistic isolation, since the neighboring Kemak in the north, Mambai in the east, Tetum in the south and west and Atoin Meto further in the west all speak Malayo-Polynesian languages, while Bunak belongs to the Papuan languages, even if there are strong influences of the Find neighboring languages again. Papuan languages are otherwise only spoken in the far east of Timor. Due to the difference in their language, the Bunak are mostly fluent in at least one Malayo-Polynesian language ( Tetum is the lingua franca in East Timor ), while their neighbors rarely learn Bunak. In the inaccessible mountains, the Bunak are relatively isolated from their neighbors. In the east their settlement area extends to the west of Manufahi and in the west to the east of the Indonesian administrative districts of Belu and Malaka .

The centers of the Bunak in East Timor are the places Bobonaro and Lolotoe in the municipality of Bobonaro, Tilomar and Zumalai in the municipality of Cova Lima , Cassa in the municipality of Ainaro and Betano and Same in the municipality of Manufahi . In the western border area of Cova Lima, the Bunak form a minority compared to the majority population of the Tetum. The settlement areas are mixed. Between Fohoren and the coast south of Suai , villages of the Tetum and Bunak alternate again and again. A total of 64,686 East Timorese call Bunak their mother tongue.

In the east of the Indonesian administrative district of Belu, the Bunak in the districts ( Kecamatan ) Lamaknen and Südlamaknen form the majority of the population, in the southeast of Raihat a minority. Likewise in the southeast of West Timor, where the Tetum make up the majority of the population. There are individual Bunak settlements between the villages of the Tetum in the Indonesian districts of Rai Manuk (Belu Governorate), Kobalima , East Kobalima and East Malaka (Malaka Governorate). The westernmost Bunak settlements are Haroe (Desa Sanleo , Malaka Timur) and Welaus (Desa Nordlakekun , Kobalima). In the northwest are the isolated Bunak villages of Faturika , Renrua (both Rai Manuk) and Babulu (Kobalima). To the east, the settlements of the Bunak lie along the road to the Desas Alas and Südalas on the border with East Timor.

The largest language groups in the sucos of East Timors

History and expansion

Mythical origin

According to legend, there was a man named Mau Ipi Guloq who was the first to domesticate the water buffalo. One day he and his brother Asan Paran caught two sows, which turned into women. His brother claimed both women for himself, which is why Mau Ipi Guloq separated from him in an argument. One day a crow disturbed his buffalo, so Mau Ipi Guloq shot a golden arrow at the bird. He had borrowed the golden blowpipe from his brother. The crow flew away with the arrow and Mau Ipi Guloq followed her into the underworld, where he met her sick ruler. Mau Ipi Guloq offered his help and discovered that his golden arrow was stuck in the ruler. He traded it for a bamboo arrow, which he soaked in his betel nut bag. The ruler of the underworld recovered and gave Mau Ipi Guloq two oranges from a tree of the underworld, which turned into princesses. Asan Paran asked his brother to swap one of his wives for one of the princesses. But when he refused, Asan Paran made sure that Mau Ipi Guloq fell into a ravine and died. However, the women of Mau Ipi Guloq found him and brought him back to life with an oil from the underworld. He returned home healthy and rejuvenated, where his brother also asked for a bath in the oil in order to become young again himself. The women of Mau Ipi Guloq heated the oil bath so much that Asan Paran died. Mau Ipi Guloq also married his brother's wives and became one of the ancestors of the Bunak.

Overview

None of the Timorese ethnic groups originally had a script. There is therefore only oral tradition of the story before European colonization. There is a rich tradition here, especially among the Bunak. The texts are recited with repetitions, rhymes and alliterations. This will help the lecturer remember the verses.

It is generally assumed that the Melanesians 3000 BC. Immigrated to Timor and from 2500 BC. Were partially ousted by descending Austronesian groups . The Fataluku are now suspected of reaching Timor after the Austronesians from the east and that they displaced or assimilated them instead. Such a scenario is also speculated among the Makasae . With the Bunak, however, only place names that are of Papuan origin can be found in the heartland, so that the Bunak must have settled here before the Austronesians. But since Bunak shares parts of non-Austronesian vocabulary with Fataluku , Makasae and Makalero , there must have been a Proto-Timor-Papua language earlier , from which all the Papuan languages of Timor originate.

The current settlement area of the Bunak is the result of various migrations. Due to population growth, the Bunak were forced to expand again and again to find new farmland. External influences led to refugee movements and forced relocations. This was the case at the beginning of the Portuguese colonization, which began with Timor in the 16th century. The Dutch extended their influence into the Bunak area by the middle of the 18th century, so that it was divided into a western, Dutch and an eastern, Portuguese sphere of interest. However, the predominance of the Europeans, mostly only nominal, remained, which was exercised over the local rulers. It was not until the early 20th century that the two colonial powers succeeded in establishing a real colonial administration. During the Second World War , the Japanese occupied all of Timor from 1942 to 1945, fought by Australian guerrilla forces . After the war the Dutch west became part of Indonesia, the Portuguese east remained a colony until 1975. When the Portuguese began to withdraw from Timor, the Indonesians first occupied the border region of East Timor. Nine days after East Timor's declaration of independence, the full invasion followed and a 24-year struggle for independence. The civilian population that fled the wilderness during the invasion only surrendered gradually to the invaders. Bunak, who had lived in the woods for three years, were the last to stand in 1979. It was not until 1999 that Indonesia withdrew and after three years of UN administration , East Timor finally gained its independence. The settlement area of the Bunak remained divided by the new national border. Since independence, more and more people have moved from rural regions to the capital Dili , including Bunak. Many of the newcomers organize themselves according to their geographical origin. Bunak speakers live in the west of the city in Comoro , Fatuhada and Bairro Pite and in the center in Gricenfor , Acadiru Hun , Santa Cruz and Lahane Oriental . In 2006 riots broke out , especially in Dili East Timorese from the east ( Firaku ) and from the west ( Kaladi ) of the country attacked each other. Bunaks belonging to the Kaladi were also involved in the clashes. Among other things, there was a conflict in Dili between Bunaks from Bobonaro and Ermera and Makasaes from Baucau and Viqueque over dominance in the market.

Heartland

The heartland of the Bunak is located in the middle east of the East Timorese municipality of Bobonaro and in the northeast of the municipality of Cova Lima. While only place names with Bunak origin are to be found here, there are also geographical names of Austronesian origin in the rest of the settlement area and in the peripheral territories only Austronesian names for settlements of the Bunak. It is concluded that the original home of the Bunak is in their heartland, from where they expanded. In the language Bunak there are influences from Kemak and less from Mambai . From this it is concluded that the original Bunak also had contact with Kemak and Mambai, which is geographically applicable to the heartland.

In the northeast, the Bunak even use the words Gaiq or Gaeq as a self-name for themselves and their language , which is derived from Mgai , the foreign name used by the Kemak. According to the oral tradition of the local Bunak, they formerly belonged to the kingdom of Likusaen (Likosaen) , which with today's Liquiçá had its center in the area of the Tokodede and Kemak. This realm is said to be responsible for the strong linguistic influence of the Kemak on the language of the Bunak. In Marobo and Obulo , Kemak mixed with the local Bunak. This led to cultural differences between this Kemak and the neighboring Kemak of Atsabe .

Between Maliana, Lamaknen and Maucatar

In traditions of the Bunak in the northwest it is reported that they originally immigrated from the east to the region south of Maliana and the present-day Indonesian districts of Lamaknen and Raihat. There they mingled peacefully, depending on the source, with the local Tetum or Atoin Meo. Place names of Austronesian origin support the information from these legends. Only in the upper Lamaknen do legends of the Bunak report that they either drove out or killed the Melus people when they came to the region. Research has not yet been able to clarify whether the Melus were Tetum, Atoin Meo or another people. Studies of the Bunak dialects suggest that Bunak from the northeast and southwest met and settled in Lamaknen. According to oral tradition, the region around Lamaknen was an autonomous region of the Tetum Empire of Wehale , which bordered on Likusaen. This influence can still be seen today in the Lamaknen dialect in loan words in ritual formulations from the Tetum.

In 1860 the region around Maucatar became a Dutch enclave, while the surrounding area was claimed by Portugal. The boundaries of the enclave were based on the boundaries of the local Bunak empires. Today the area belongs to the Sucos Holpilat , Taroman , Fatululic , Dato Tolu and Lactos . The area of the then enclave Maucatar is still inhabited by a large majority of Bunak. However, place names can also be found here that have their origin in the Tetum. It is therefore assumed that the Bunak later immigrated to this region and largely assimilated the Tetum, which today only form a small minority here.

In 1897 there were several battles for areas in Lamaknen between the northeastern kingdom of Lamaquitos (Lamakhitu) and the southern Lakmaras , which had its allies with the Bunak in the southwest. The end of this last traditional conflict between the indigenous empires of the region meant that the Bunak in Lamaknen gradually abandoned their hilltop villages and built houses close to water points. Spread over a larger area, the clan members now only come to their clan houses to perform ceremonies. As a result of the various territorial shifts between the Bunak empires, however, the demarcation between the two colonial powers Portugal and the Netherlands remained controversial for a long time and was the subject of lengthy negotiations. In Lakmaras in the same year there were deaths in clashes between Dutch and Portuguese troops. The claim of the Dutch to Maucatar was justified so far with the suzerainty over Lakmaras, which created a connection to Maucatar. In the meantime, however, Lakmaras had become a subject of the kingdom of Lamaquitos and this was part of the Portuguese sphere of influence with the Treaty of Lisbon in 1859. According to the agreements that were valid until then, Maucatar should have fallen to Portugal as an enclave. On the other hand, the realm of Tahakay ( Tahakai, Tafakay, Takay, today in southern Lamaknen) had fallen to the realm of Lamaknen. But Tahakay belonged to the Portuguese sphere of influence, Lamaknen to the Dutch. Portugal resisted this loss in the negotiations of 1902 and therefore now demanded the entire Dutch territory in central Timor. With the The Hague Convention of October 1, 1904, a compromise was reached: Portugal was to receive Maucatar in exchange for the Portuguese enclave Noimuti in West Timor and the border areas of Tahakay, Tamira Ailala ( Tamiru Ailala , today in the Malaka administrative district) and Lamaknen. Portugal ratified the treaty until 1909, but then there was a dispute over the demarcation of the border on the eastern border of Oe-Cusse Ambeno . In 1910 the Netherlands took advantage of the confusing situation after the fall of the Portuguese monarchy to re- appropriate Lakmaras with the help of European and Javanese troops.

In February 1911, following the 1904 Convention, Portugal attempted to occupy Maucatar. However, in June it was faced with a superior Dutch force made up of Ambrose infantry, supported by European soldiers. On June 11th, the Portuguese occupied Lakmaras territory, but on July 18th, Dutch and Javanese troops also invaded the area. After the victory of the Dutch, the Portuguese now sought a peaceful settlement. They soon got into trouble because of the Manufahi rebellion , which made them ready to negotiate. On August 17, 1916, the treaty was signed in The Hague , which largely defined the border between East and West Timor that still exists today. On November 21st, the territories were exchanged. Noimuti, Maubesi , Tahakay and Taffliroe fell to the Netherlands, Maucatar to Portugal, which caused panic there. Before the handover to the Portuguese, 5000 locals, mostly Bunak, destroyed their fields and moved to West Timor. In Tamira Ailala, they would have preferred to stay with Portugal while the rulers of Tahakay welcomed the move to the Dutch.

Only a few generations ago, Bunak from the east founded villages in the lowlands around Maliana, for example Tapo / Memo . Even today these villages have ritual relations with their ancestral villages in the highlands.

After the Second World War, Bunak fled Lebos in what was then Portuguese Timor to Lamaknen. They feared reprisals after collaborating with the Japanese during the Battle of Timor . The then ruler of Lamaknen, the Loroh (Loro) Alfonsus Andreas Bere Tallo, allocated land to the refugees, where they founded the village of Lakus (in today's Desa Kewar ).

From August 1975, as a result of the civil war between FRETILIN and UDT, a movement of refugees came from East Timorese villages on the border. There were also many bunaks among them. They came from Odomau , Holpilat, Lela , Aitoun , Holsa , Memo and Raifun . At the end of August, the conflict also crossed the border. Villages were destroyed on both sides, for example Henes in Desa of the same name on the west Timorese side, which has not been rebuilt since then. The invasion of East Timor by Indonesia, which took place in the following months, forced more Bunak to flee their villages. Some crossed the border, others sought refuge in the woods, where they sometimes spent up to three years. In this way, village communities were torn apart and resettled in different places until 1999. A fate that befell the village of Abis in Lamaknen. Although the residents returned to their village after their escape in 1975, the village near the East Timor border was later burned down. Other refugees came to Lamaknen during the Indonesian Operation Donner in 1999 and some have stayed until today. There were fights with the locals. Fields, huts and roads were destroyed.

Southwest of Cova Lima

The Bunak immigrated to the southwest of Cova Lima in two independent waves only in the recent past. The older group lives in the slightly higher areas in Beiseuc (formerly Foholulik , 2010: 30% Bunak) and Lalawa (35% Bunak). They came in a large stream of refugees from the Bobonaro community when they fled the Japanese army during World War II. Allied guerrilla units had operated against the Japanese from Lolotoe and the town of Bobonaro , whereupon the Japanese troops carried out retaliatory measures against the civilian population in Bobonaro in August 1942. This presumably killed tens of thousands of people and drove others to flight.

Last came those Bunak who settled in the lowlands between Suai and the border. They were forcibly relocated from northern Sucos Cova Limas, such as Fatululic and Taroman, by the Indonesian occupation forces. The official goal was a development program for rice cultivation. But for better control, parts of the population from remote areas were forcibly resettled from 1977 in many places in East Timor in order to prevent support for the East Timorese liberation movement FALINTIL . Indonesia set up so-called "transit camps" for them in East Timor, to which hundreds of thousands of civilians were also brought.

Malaka and southern Belu

The bunak of the village of Namfalus (Desa Rainawe , Kobalima) come from the same wave of flight from the Japanese in World War II as the bunak south of Fohorem . The other bunaks in this region are the descendants of the 5000 refugees from Maucatar who left the former Dutch enclave after it was taken over by the Portuguese. More Bunak joined these villages when they fled the violence in East Timor in 1975 and 1999.

The resettlement of the Maucatar-Bunak led to land disputes with the local Tetum, which is why the Bunak had to keep moving. It was not until the 1930s that the administration succeeded in resettling the refugees where they are today. The Bunak of the individual places still trace their origin to certain places in Maucatar, for example those from Raakfao ( Raakafau , Desa Babulu) on Fatuloro and the Bunak from Sukabesikun (Desa Litamali , Kobalima) on Belecasac . They merge more and more with the neighboring Tetum.

Eastern Cova Lima

The Bunak settlements from Suai to Zumalai were also only recently founded. Before that, the region was uninhabited. These start-ups also have ties to their places of origin. Thus Beco deep relationships with Teda , east of lolotoe, even if the exodus already back several generations. Their dialect is actually close to that of the Lolotoe region, even if some vocabulary has been adopted from the Southwest dialect. Other settlements only emerged during the Indonesian occupation, when entire villages were resettled from the north along the southern coastal road around Zumalai. Their dialect corresponds completely to that of the highlands.

Ainaro and Manufahi

In the south of Ainaro and in the southwest of Manufahi the Bunak live mainly with the Mambai. The dialect of the Bunak shows that they come from the northeast of their language area. Due to the close contact with the Mambai, most of the Bunak here are bilingual with this Malayo-Polynesian language and their mother tongue also shows influences from the Mambai.

In Mau-Nuno , 60% Tetum speakers with 30% Bunak and 10% Mambai live in a village that was only combined from three villages during the Indonesian occupation. In Suco Cassa, the Bunak form the majority with a 55% population, along with Tetum and a small Mambai minority. In Foho-Ai-Lico , too , the Bunak make up the majority. According to oral tradition, they originally come from the western Ainaro, which they left due to conflicts with other Bunak during the Portuguese colonial period. The linguistic peculiarities of the three Bunak groups in Ainaro suggest a common origin.

This origin is controversial. While parts of the Bunak state that they immigrated to the region later, others claim that they were the original inhabitants. However, all Bunak settlements have Austronesian place names, which would indicate an original Malayo-Polynesian settlement. Place names that begin with Mau (Mau-Nuno, Mau-Ulo , Maubisse ) are typical for the settlement areas of the Mambai, Kemak and Tokodede. In the heartland of the Bunak there is no such thing. Other place names are clearly of Mambai origin, such as Beikala . At means "grandparents", kala "ancestors".

In addition to the three main groups of the Bunak in Ainaro, there are two other, smaller groups that were only relocated here from the region around Zumalai during the Indonesian occupation. The first group lives in the villages Civil (Sivil) and Lailima (both in Suco Cassa). In Suco Leolima , Hutseo and Hutseo 2 Bunak live surrounded by Mambai settlements. The inhabitants of the four villages speak the northeast dialect, with the variations typical of Zumalai.

There are four isolated bunak villages in Manufahi. The oldest of them is Loti in the southeast of Suco Dai-Sua . The Bunak here emigrated from Ai-Assa in 1891 after a conflict with the ruler of Bobonaro. According to oral tradition, the residents of Ai-Assa had killed his wife, whereupon Bobonaro requested assistance from the Portuguese in August. After several skirmishes, some of the residents of Ai-Assa fled to Manufahi. They initially settled a little further north of today's Lotis, where they only had contact with Mambai and Lakalei speakers. This resulted in a unique deviation and even word creations of the local Bunak dialect.

After the failed Manufahi rebellion , part of the Bunak of Loti was resettled by the Portuguese to the location of today's Lotis. Others were settled in two new villages in Suco Betano. One is called on Mambai Bemetan and on Bunak Il Guzu (in German "Black Water"), the second is Leo-Ai (Leoai , Leouai) . During the Indonesian occupation, the Bunak that remained in the old Loti were also relocated to the new Loti. These three villages share their extraordinary dialect.

The fourth bunak village in Manufahi is Sessurai (Sesurai) in Suco Betano, on the road between Loti and Leo-Ai. According to their traditions, these Bunak fled from the region around Zumalai to Manufahi during the Portuguese colonial times. Their dialect corresponds to that of Zumalai, but has adopted some words from the Loti-Bunak.

Culture

Social organization

The traditional isolation was also reinforced by the reputation of the Bunak. They have been described as rough and aggressive. This characterization can also be found in a Bunak legend in which the Kemak were said to have long ears and the Bunak short. The metaphorical length of the ears in the Bunak refers to a quick-tempered and impatient temperament, while the Kemak are described as calm and patient.

Although Bunak and Atoin Meto differ culturally, the social organization and ecology of both cultures belong in the same context: the cultures of Atoin Meto and Bunak benefit from each other. The rapprochement of the Bunak in cultural and linguistic terms goes so far that Louis Berthe described them in 1963 as a mixed ethnicity with Papuan and Austronesian roots.

The smallest social unit in the Bunak society is the clan or the house, which is called deu in the upper Lamaknen, for example . Several clans live together in villages (tas) . Each village has its own territory. The clans each have a different level of status. The noble clans are called sisal tul ( German bone pieces ). The name is derived from a ritual in which the bones of the sacrificial animal belong to the noble clan. The highest of the noble houses belongs to the clan of the "female" chief. This man decides if there are problems in the village. The second highest clan is the “male” chief who takes care of the village's relations with the outside world. The village chiefs' advisors come from other clans. Despite their extensive power (oe nolaq) , the two chiefs are subordinate to the ritual chief. He has a limited power (oe til) within the affairs of the clan. Together with one of his sisters, the ritual chief is also the guardian of the sacred objects in the clan house. In Lamaknen the siblings are called the “man who holds the black basket” (taka guzu hone mone) and the “woman who holds the black basket” (taka guzu hone pana) .

The different clans are linked to one another in the system of malu ai . In this case, the malu clan gives women and female goods such as pigs and clothes in a partnership, while the ai baqa clan includes men and male goods. This used to include gold, silver and water buffalo, now replaced by money and cattle. On festive occasions such as funerals or the repair of the clan house, goods are exchanged again between malu and ai baqa . However, women rarely leave their ancestral clan. Most of the Bunak have a matrilineal system of succession. The man traditionally moves to the bride's clan ( uxoril locality ), where the later children also grow up. The husband has to look after his children and the wife as mane pou ("new man"), but is not considered a family member. He also has no claims or rights against his wife and children, even if he had to pay a high bride price. In 1991 it was about $ 5100. If the wife dies first, the widower has to leave the village and his children and return to his old home village. Certain ceremonies can make this necessary. He is not allowed to take material assets with him, so that he has to rely on the help of his ancestral clan and family. As a stranger to the clan, he does not receive any support from his own children. If the woman changes to the ai baqa clan, one speaks of cutting off the woman from her clan. She is accepted into her husband's clan, where the family forms a new line of descent (dil) with the establishment of a new malu – ai baqa relationship. The children also belong to the father's clan. Clans can have 15 malu relationships, but there are never more than three to six dil . They keep their status in the further course of the dam line. The members of the dil bear the name of the maternal clan and retain their property and sacred objects. In Ainaro, however, the influence of the neighboring Mambai has resulted in a patrilinear structure. Mambai and Bunak also share legends here. The Bunak from Mau-Nuno are derived from the same mythical pair of ancestors and the summit of the mountain from which they come has both a Bunak and a Mambai name.

Sacred objects are passed on from men to their sister's sons. The father can only bequeath objects to the son that he has acquired in the course of his life. Other sacred objects belong to the entire clan. They are mostly considered a source of life energy. They are kept in the clan houses, where only the guards live today. In the past, all clan members lived together in the clan house. Sometimes a young couple still lives with the guards to help them with their everyday work. Each clan house has an altar that can be both inside and outside the house. In the house, the altar is on one of the two posts that support the ridge beam (lor bul) . Opposite is the fireplace. All lor bul of the clan houses are aligned with the common altar of the village ( bosok o op , German altar and height ) . The village altar ( bosok o op ) represents the life energy of the residents. It is also called pana getel mone goron - "root of women, leaves of men" - a metaphor for vitality: leaves move and roots enable plants to absorb water. The longer the roots, the longer the plant will live. If Bunak wish each other a long life, they say i etel legul ( German let our roots be long ) or i somewhat huruk ( German let our roots be cool ). Coolness, combined with water, symbolizes fertility; Heat is associated with danger and death. Other altars can be at water sources, others were only used in the event of war.

Rites in agriculture in llama

When the Bunak reached Lamaknen, according to legend, they asked their ancestors in heaven for seeds so they could plant fields. Bei Suri , a man who had joined the Bunak, was sacrificed and burned on a field altar . From the different parts of his body appeared the different crops that the bunak plant. Lore in verse names various forms of rice , which is still used today for ceremonial food. But there are also versions that include corn in the legend, which is the main food source of the Bunak in Lamaknen today. But this was only brought to Timor by the Europeans. The rain is also related to the self-sacrifice of Bei Suri . After his death, he urged people not to cry anymore and took the form of a bird that foretold the rain.

From the 1970s to the early 1980s, the researcher Claudine Friedberg researched the rituals of the Bunak in Abis (Lamaknen) in agriculture and described in detail the ceremonies of the Bunak in this region. However, the place no longer exists and a road now connects the region with the outside world, which at that time could only be reached by horse. Agriculture here is entirely dependent on the amount of monsoon rainfall . The reliability of a sufficient amount of rain is the critical moment of the agricultural calendar at the time of sowing. It takes place in Lamaknen before the rain comes between October and December. By slash and burn the fields are ready, the Lord of the seed and the rice master put the dates fixed for various ceremonies. The Lord of the Saat belongs to the clan to which the legend of the sacrifice near Suris is ascribed. However, it is not one of the noble houses. The rice masters are the guardians of the sacred objects of certain high-ranking clans.

Before the sowing, there is a hunt lasting several days, during which the men mostly kill feral pigs. In the rest of the year, hunted for daily needs. Game has become rare anyway due to the population growth, so that the prey is less important than preventing possible game damage in the fields. The prey is associated with the kukun , those in the dark. This refers to the local spirits of the late Melus , who were once expelled from the region by the Bunak. The kukun are the masters of heaven and earth ( pan o muk gomo ) and the masters of prey. On the other hand, the living stand as the roman , “the clear ones”. For the kukun there are small, inconspicuous altars made of just a few stones scattered around the area. The Bunak connect with the kukun via this muk kukun . The main altar is near the village. On the evening of the first day of the hunt, the Lord of the Seed puts a liana around the broad pile of stones and ties its ends to two wooden stakes that are a few centimeters apart. The liana symbolizes the encircling of the pigs, which can only escape through a narrow gate where the hunters are waiting for them.

On the following day , the rice masters sacrifice betel nuts, some alcohol and feathers from a live chicken on the muk kukun , which is located in the selected hunting area, so that the masters of the country give up the wild pigs. The rice masters lie down in front of the altar and pretend to be asleep so that the pigs should also fall into a deep sleep. This makes it easier for the hunting dogs to scare them off later. The prey from the first day of the hunt is brought back to the village in the evening, where a woman from the clan of the Lord of the Saat greets the prey like a guest with betel. This is followed by “welcoming the smoke of the fire” ( hoto boto hosok ). The master of the seeds and the rice masters recite verses on the village altar about the seeds produced by the body of Bei Suri . One of the Lords of the Word sacrifices a rooster with red feathers by killing it. Usually the sacrificial animal's throat is cut, but here it is feared that the roots of the seeds could be cut with a knife. The Lord of the Word recites a welcome text and prays to the Lord of the village altar. This refers to the Melus , who originally erected the altar, and the first Bunak to take over it. The coming planting season is prophesied from the cock's appendix. The boiled rooster is disassembled and distributed in small baskets of boiled rice. Some of them are offered to the altar and placed on its top. Then they are handed over to the clan of the female chief. Those baskets at the foot of the altar go to the Sabaq Dato clan, the Glan of the female chief of the Melus . A basket is offered to Bei Suri . The Lord of the Seed receives this. The other baskets are distributed among the hunters.

On the night of the third day of the hunt, the lord of the seeds and the rice masters bring the meat, which is believed to contain the seeds of the future harvest, to the lotaq altar on the outskirts of the village. This is done in silence so as not to attract attention in carnivorous animals. At the lotaq , birds, insects and other animals are symbolically fed rice and chicken to keep them away from the seeds. On the afternoon of the third day, the various clans visit their graves and bring them fruit and special cakes. At the graves, you meet with the members of the respective malu clan, who also bring fruit and cakes with them. After being offered to the deceased, the offerings are given to the ai baqa clan.

On the fourth day, after the last hunt, a final ritual is performed together. Women from all the clans in the village bring boiled rice in large baskets to the lord of the seeds at the lataq altar. This is distributed to the hunters who have injured or killed a pig. It is a kind of compensation, because contrary to the usual custom, they do not receive any part of the booty from this traditional hunt. The meat is only consumed by the lord of the seeds and the rice masters within the ritual circle. It is precisely at this point in time that the first heavy rain is expected to fall. It is in the experience of the rite leaders that ritual and rain coincide on the same day and thus the success of the harvest. The final ritual is even more elaborate every three years. This period coincides with the three-year cycle of slash and burn. From the next day onwards, the fields are sown after a piglet and a goat have been slaughtered at the respective field altar. The blood of the piglet is considered cold and is also said to cool the semen. For the bunak, cold is a synonym for fertility, while heat is associated with death, danger and struggle. The goat is said to carry the souls ( melo ) of the felled trees to the afterlife on the tip of its horns . However, Friedberg discovered in 1989 after a visit to the region that this ritual was no longer performed at the field altars. The reason was that there was simply no one left to afford the offerings. Instead, a common cooling ritual for all villagers was held at the village altar. The ritual for the souls of the trees was omitted, possibly because there were simply no more trees in the fields due to the short frequency of slash and burn.

In the fields, the seeds are sown with a digging stick immediately after the slash and burn . The grave stick has an eight to ten centimeter large metal sheet and is also important in the wedding ceremony. There were no irrigated fields in Abis, but in other parts of Lamaknen. These are ordered with the help of water buffalo and cattle.

As long as the crops are not ripe, there are strict harvest bans , which are monitored by the captain and the Makleqat ( see German hear ) who support him . The captain himself is subordinate to the lord of the first fruits ( hohon niqat gomo ), also called lord of the germs, sandalwood and beeswax ( kosoq sable turul wezun gomo ). Sandalwood and beeswax used to be important trading goods, the extraction of which was under the control of the local rulers in order to protect the population. In the Atoin Meto in Oe-Cusse Ambeno, the Tobe has a similar function as the administrator of the resources. The captain and master of the first fruits came from the same clan of the Bunak in Abis, the Sabaq Dato.

Mangoes and light nuts are the first to ripen. The entire harvest of both fruits is collected in the main square of the village. The clans of the female and male chiefs are the first to receive their share from the mangoes, which is also greater than that of the others. Only the female chief receives a share of the light nuts. The rest is kept by the captain for general use.

literature

- Louis Berthe: At Gua: Itinéraire des ancêtres. Myth of the Bunaq de Timor. Texts Bunaq recueilli à Timor auprès de Bere Loeq, Luan Tes, Asa Bauq et Asa Beleq . (= Atlas ethno-linguistique. Series 5, Documents ). Center national de la recherche scientifique, Paris 1972.

- Claudine Friedberg: Boiled Woman and Broiled Man: Myths and Agricultural Rituals of the Bunaq of Central Timor. In: James J. Fox (Ed.): The Flow Of Life. Essays On Eastern Indonesia . (= Harvard Studies in Cultural Anthropology. 2). Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA a. a. 1980, ISBN 0-674-30675-9 , pp. 266-289.

- Claudine Friedberg: La femme et le féminin chez les Bunaq du center de Timor . 1977.

supporting documents

- Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- and Volkenkunde, Rituals and Socio-Cosmic Order in Eastern Indonesian Societies. Part I Nusa Tenggara Timur 145 (1989), no: 4, Leiden, pp. 548-563.

- Geoffrey C. Gunn: History of Timor. Technical University of Lisbon (PDF file; 805 kB)

- Antoinette Schapper: Crossing the border: Historical and linguistic divides among the Bunaq in central Timor.

- Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq: The homeland and expansion of the Bunaq in central Timor. In: Andrew McWilliam, Elizabeth G. Traube: Land and Life in Timor-Leste: Ethnographic Essays. 2011, pp. 163-186.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 164.

- ^ A b Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 163.

- ↑ a b c d Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 175.

- ↑ Direcção-Geral de Estatística : Results of the 2015 census , accessed on November 23, 2016.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 165.

- ↑ Statistical Office of East Timor: Results of the 2010 census of the individual sucos ( Memento of January 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Yves Bonnefoy: Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press, 1993, ISBN 0-226-06456-5 , pp. 167-168.

- ^ Geoffrey C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 4.

- ^ University of Coimbra : Population Settlements in East Timor and Indonesia. ( Memento of February 2, 1999 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Andrew McWilliam: Austronesians in linguistic disguise: Fataluku cultural fusion in East Timor. ( Memento of the original from November 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 171 kB)

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 182.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 182-183.

- ^ A b Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 168.

- ↑ a b c "Chapter 7.3 Forced Displacement and Famine" (PDF; 1.3 MB) from the "Chega!" Report of the CAVR (English)

- ↑ James Scambary: A Survey of Gangs and Youth Groups in Dili, Timor-Leste. 2006 (PDF; 3.1 MB)

- ^ A b Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 169.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 170.

- ^ Andrea K. Molnar: Died in the service of Portugal.

- ↑ a b c Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 171.

- ^ Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. P. 551.

- ↑ a b c d Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 173.

- ↑ a b c d Hague Justice Portal: Island of Timor: Award - Boundaries in the Island of Timor ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English)

- ↑ a b c Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 174.

- ^ A b c Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. P. 550.

- ↑ a b c d Antoinette Schapper: Crossing the border. Pp. 7-8.

- ^ A b Geoffrey C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 77.

- ^ Geoffrey C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 92.

- ↑ "Part 3: The History of the Conflict" ( Memento of the original from July 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. from the "Chega!" report by CAVR (English, PDF; 1.4 MB)

- ^ A b c Antoinette Schapper: Crossing the border. P. 10.

- ^ A b c d e Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. P. 549.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Crossing the border. Pp. 10-11.

- ^ Frédéric Durand: Three centuries of violence and struggle in East Timor (1726-2008). Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, June 7, 2011, ISSN 1961-9898 , accessed May 28, 2012 (PDF; 243 kB).

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 175-176.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 176-177.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 177.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 177-178.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Results of the 2010 census for the Suco Mau-Nuno ( Tetum ; PDF; 8.2 MB)

- ↑ a b c d Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 179.

- ↑ Results of the 2010 census for the Suco Cassa ( Tetum ; PDF; 8.2 MB)

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 180.

- ^ A b Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 181.

- ^ A b Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 179-180.

- ↑ UCAnews: Bunaq men seek emancipation from matriarchal society. August 7, 1991, accessed January 21, 2014.

- ^ A b c Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. P. 552.

- ↑ a b c d e f Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. P. 555.

- ^ A b c d Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. P. 553.

- ^ A b c d Claudine Friedberg: Social Relations of Territorial Management in Light of Bunaq Farming Rituals. P. 556.

- ^ Laura Suzanne Meitzner Yoder: Custom, Codification, Collaboration: Integrating the Legacies of Land and Forest Authorities in Oecusse Enclave, East Timor. Dissertation . Yale University, 2005, p. Xiv. ( PDF file; 1.46 MB ( memento of March 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive )).