Ainaro (Municipality)

|

Munisípiu Ainaru (tetum) Município de Ainaro (port.) |

||

|

||

| Data | ||

| Capital | Ainaro | |

| surface | 802.59 km² (9.) | |

| Population (2015) | 63,136 (10.) | |

| Population density | 78.67 inhabitants / km² (6.) | |

| Number of households (2015) | 10,601 (9.) | |

| ISO 3166-2: | TL-AN | |

| Administrative offices | Residents | surface |

| Ainaro | 16,121 | 237.65 km² |

| Hato-Udo | 10,299 | 246.99 km² |

| Hatu-Builico | 12,966 | 129.34 km² |

| Maubisse | 23,750 | 191.60 km² |

| map | ||

|

||

Ainaro ( tetum Ainaru ) is a municipality in East Timor . It is located south of the state capital Dili and extends from the central ridge of the island of Timor with almost 3000 m to the alluvial plains on the south coast of the Timor Sea . The Mambai are the dominant ethnic group in Ainaro. Bunak , Kemak and Tetum also live there .

The name of the community is derived from Ainaru , the Mambai word for "high tree".

geography

Overview

Like the other communities in East Timor, Ainaro was still referred to as a " district " until 2014 . Subordinate to it are the “ administrative offices ”, which were previously called “ sub- districts ”. The municipality of Ainaro is divided into the administrative offices of Ainaro , Hato-Udo , Hatu-Builico and Maubisse . During the Indonesian occupation around 1977, the then sub- district Turiscai was separated and attached to the Manufahi district , for which Hato-Udo moved from Manufahi to Ainaro. In 2003, the Mape-Zumalai sub- district was separated from Ainaro and added to the Cova Lima district.

The capital of the municipality is the Ainaro of the same name . The sucos Ainaro and Maubisse are defined as " urban ". 13,066 inhabitants (2010) live in the two cities together.

Since the territorial reform of 2015, Ainaro has an area of 802.59 km² (before 869.79 km²) and is located on the south coast of East Timor, on the Timor Sea. In the southeast is the Ponta Lalétec . In the north it borders on the municipality of Aileu , in the east on Manufahi , in the south-west on Cova Lima , in the west on Bobonaro and in the north-west on Ermera . In the north and in the center of Ainaro there is mountainous terrain with several high elevations, such as the Suro-lau ( 1388 m ), the Mamalau ( Manlau , 1400 m ) and the Cablac ( 2180 m ). Towards the south the land slopes down to the sea and becomes flatland savannas. 45% of the area of the municipality is over 1000 m , another 36% over 100 m . From the administrative office of Hatu-Builico an ascent route leads to the Tatamailau ( 2963 m ), Timor's highest mountain, the summit of which lies across the border in neighboring Ermera. The area around the Tatamailau is classified as an Important Bird Area because of its importance for the bird world . Since 2000 the summit of Saboria (over 2000 m ) and the surrounding forests have been a wildlife sanctuary. To the east of the capital, Ainaro, is the Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão National Park , which extends to the neighboring municipality of Manufahi.

The most important river is the Belulik ( Bé-lulic ), which flows through most of the municipality from north to south and whose numerous source rivers arise in the Ainaro mountains. In the southeast, the Caraulun ( Carau-úlun ) with its numerous river islands forms the border with Manufahi. Some of its source rivers arise in the Maubisse administrative office, in the north of Ainaros. In the west, the Mola flows along the border to Cova Lima, before turning there.

Hut at about 2500 m altitude on the Tatamailau

The Cablac

climate

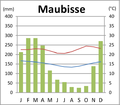

The rainy season falls between October and June. At around the same time, temperatures also rise. The coldest month is August. In the capital Ainaro, temperatures can then drop to almost 15 ° C, in the mountainous Maubisse even lower.

- Climate diagrams

fauna

Some conspicuous representatives of Timor’s reptiles , such as the Timor kite , the Elbert emerald skink or the tokeh , are missing in Ainaro. This was found in Maubisse previously unknown types of Smooth Nachtskinke ( Eremiascincus ) and rainbow skink ( Carlia ), and unspecified Waldskinke ( Sphenomorphus ). In keeping with the name, the flower pot snake ( Indotyphlops braminus ) was dragged into the mountains of Maubisse in plant tubs.

Among the amphibians of Timor , the otherwise common rice frogs ( Fejervarya ) are missing in Ainaro . The black- scarred toad ( Bufo melanostictus ) that has immigrated to Timor in recent years has not yet reached Ainaro. The whitebeard rowing frog ( Polypedates leucomystax ) could be detected for this.

Residents

63,136 (2015, 2011: 62,171 inhabitants) live in the Ainaro administrative office, with the northern administrative offices being much more densely populated than the southern flatlands. The total population density is 78.67 inhabitants per square kilometer. The average age is 16.7 years (as of 2010). Between 1990 and 2004 the number of inhabitants grew by 1.36% annually. In 2004, every woman in Hato-Udo had an average of 6.03 children, the number rose to the north over 8.09 children in Ainaro and 8.38 children in Hatu-Builico, up to 9.35 children per woman in Maubisse (national average 6 , 99). In 2002, child mortality in Hatu-Builico was 186 deaths per 1,000 live births (1996: 193), in Maubisse 122 (188), in Hato-Udo 98 (115) and in Ainaro 79 (141). The national average was 98. The Ainaro Administration Office can point to one of the largest declines in child mortality in the country.

62.4% (2015 census) of the population speak the national language Mambai as their mother tongue. 29.1% of the residents of Ainaros speak Tetum and 7.5% speak Bunak , especially in the Sucos Cassa , Mau-Nuno and Foho-Ai-Lico . About 400 inhabitants (0.7%) name Kemak as their mother tongue. They live mainly in the sucos Mau-Ulo and Leolima . If the second languages are also taken into account, in 2015 92.9% spoke Tetum, 30.6% Bahasa Indonesia, 30.1% Portuguese and 13.3% English .

In the south of Ainaro, the Bunak live mainly with the Mambai. The dialect of the Bunak shows that they come from the northeast of their language area. Due to the close contact with the Mambai, most of the Bunak here are bilingual with this Malayo-Polynesian language and their mother tongue also shows influences from the Mambai.

In Mau-Nuno, 60% Tetum with 30% Bunak and 10% Mambai live in a village that was only combined from three villages during the Indonesian occupation . In Suco Cassa, the Bunak form the majority with a 55% population, along with Tetum and a small Mambai minority. In Foho-Ai-Lico , too , the Bunak make up the majority. According to oral tradition, they originally come from the western Ainaro, which they left due to conflicts with other Bunak during the Portuguese colonial period. The linguistic peculiarities of the three Bunak groups in Ainaro suggest a common origin.

This origin is controversial. While parts of the Bunak state that they immigrated to the region later, others claim that they were the original inhabitants. However, all Bunak settlements have Austronesian place names, which would indicate an original Malayo-Polynesian settlement. Place names that begin with Mau (Mau-Nuno, Mau-Ulo , Maubisse ) are typical for the settlement areas of the Mambai, Kemak and Tokodede . In the heartland of the Bunak further west there is no such thing. Other place names are clearly of Mambai origin, such as Beikala . At means "grandparents", kala "ancestors".

In addition to the three main groups of the Bunak in Ainaro, there are two other, smaller groups that were only relocated here from the region around Zumalai ( Cova Lima municipality ) during the Indonesian occupation . The first group lives in the villages Civil (Sivil) and Lailima (both in Suco Cassa). In Suco Leolima , Hutseo and Hutseo 2 Bunak live surrounded by Mambai settlements. The inhabitants of the four villages speak the northeast dialect, with the variations typical of Zumalai.

In 2004, 98.3% of the population were Catholics , 0.9% followers of the traditional, animistic religion of Timor , 0.6% Protestants and 0.1% Muslims . In 2015 there were 99.1% Catholics, 0.9% Protestants, 0.03% Muslims and only 19 animists. The influence of the old faith is more evident in customs and traditional festivals than in the actual creed. The Protestants have their centers in Faulata and the city of Ainaro (Administrative Office Ainaro), in Tolemau (Administrative Office Hatu Builico) and in Foho-Ai-Lico (Administrative Office Hato-Udo). The relationship between the various groups is neighborly.

Holy House ( Uma Lulik ) in Nuno-Mogue

Inside a holy house in Tartehi

In 2015, 40.3% of residents aged three or over attended school. 23.2% had left school. 35.1% have never attended school, which is around 6% above the national average. 5.4% of the residents of Ainaro have only attended pre-school, just under a third only attended primary school. Just under a quarter of the population have completed secondary schools. Only 2.7% have a diploma or a degree; here, too, the numbers are worse than the national average. The illiteracy rate in 2015 was 24.8% (women: 24.7%; men: 24.9%). In 2004 it was still 63.0%.

| Education | Graduation | ||||||||||

| at school | Finished school | never in a school | Preschool | primary school | Pre- secondary |

Secondary | Diploma / University of Applied Sciences |

university | No graduation | ||

| Women | 39.2% | 21.5% | 38.0% | 5.0% | 26.3% | 12.4% | 11.6% | 0.5% | 1.8% | 1.5% | |

| Men | 41.4% | 24.9% | 32.3% | 5.8% | 30.4% | 12.5% | 11.9% | 0.6% | 2.5% | 1.2% | |

| total | 40.3% | 23.2% | 35.1% | 5.4% | 28.4% | 12.4% | 11.8% | 0.5% | 2.2% | 1.4% | |

history

Portuguese colonial times

With the introduction of the colonial administration, the area of Ainaro was assigned to the Alas military command , which included areas from today's Cova Lima to Manufahi. In 1883 the areas were separated to the west and merged with today's Bobonaro.

In 1902 an uprising against the Portuguese colonial rulers in Ainaro failed . Five years later, Nai-Cau , Liurai of Soro, rebelled against the superior ruler of Atsabe . In September he achieved the independence of his territory within the Timorese rule system. Soro's territory stretched from Atsabe in the northwest to Manufahi in the east and south. When the Manufahi rebellion broke out in 1911 , Nai-Cau was on the side of the colonial rulers and Soro became one of the bases of the Portuguese in the fight against Manufahi. Maubisse in turn supported Dom Boaventura , the rebellious Liurai of Manufahi. In 1912 Boaventura attacked the Portuguese military post in Ainaro, but was repulsed with the support of Nai-Cau. On May 27, there was a great battle between the colonial troops and the Boaventura at Cablac. The Timorese rebels had holed up here taking advantage of the rugged landscape, but were defeated by the overwhelming strength of the Portuguese and their allies and forced to flee. Since then, the Cablac has been transfigured as Manufahi's holy mountain.

During the Second World War , Portuguese Timor was occupied by the Japanese from 1942 and was the scene of the Battle of Timor , in which Australian commandos and part of the population fought against the occupiers using guerrilla tactics . The non-Christian population of Maubisse sided with the other side and used the Japanese occupation to attack the Portuguese and Christianized, pro-Portuguese Timorese of Ainaro and Same . During the Maubisse rebellion on August 11th, a Portuguese official was killed by the Colunas Negras , but the colonial power and the Moradores allied with them were able to drive the rebels into the mountains. Dom Aleixo Corte-Real , nephew and successor of Nai-Cau as Liurai von Soro, sent his son with 350 men to take action against the Colunas Negras . From March 1943, the Japanese began air raids against Ainaro and 7,000 to 8,000 Colunas Negras invaded to fight anti-Japanese forces.

In May, Dom Aleixo and his people had to flee Soro and retreat to Hato-Udo, where they met Quei-Bere, the boss of Foho-Ai-Lico. Quei-Bere had already switched to the Japanese side. He offered Dom Aleixo protection and took him to Hato-Udo , where they arrived on May 5, 1943. 500 Colunas Negras and regular Japanese troops reached the village on the same day and surrounded Dom Aleixo. The warriors from Ainaro ran out of ammunition and had to surrender. Dom Aleixo, his family, Nai-Chico (head of Hato-Udo) and other men were arrested. Legend has it that he refused to recognize Japanese authority and refused to surrender the Portuguese flag he was hiding.

Dom Aleixo saw no chance to escape. According to Japanese reports, he said goodbye to his children, told them to protect their mother and face his death. Then he tried to kill the Japanese guard at the entrance. After a brief struggle, Dom Aleixo was stabbed in the chest with a sword. Nai-Chico was shot dead by another Japanese man. The children of Dom Aleixos also intervened in the kamof and perished in the process. In the end, 80 men from Ainaro were dead, only three remained alive. The women were put in charge of Quei-Bere. A Timorese named Siri-Buti cut off Dom Aleixo and Nai-Chico's heads according to the Timorese war tradition ( Funu ) and brought them to Betano . Portuguese sources state that Dom Aleixo and his family were executed.

Even in the Portuguese colonial times, Dom Aleixo was stylized as a folk hero. A memorial commemorates him in the municipality capital Ainaro. Evaristo de Sá Benevides, ruler of Maubisse, was also killed by the Japanese in 1943. A memorial in Maubisse commemorates him today

After the war, the area of Ainaro was part of the district ( Portuguese Conselho ) of Suro until 1967 when the Ainaro district was created as a separate administrative unit and separated from Manufahi in the east.

Indonesian occupation

|

District President (Bupati) |

|

| Moisés da Silva Barros ( APODETI ) | May 1976-1984 |

| Lieutenant Colonel H. Hutagalung (military) | 1984-1994 |

| José AB dos Reis Araújo ( APODETI ) | 1994-1999 |

| Norberto de Araújo ( APODETI ) | 1999 |

| Evaristo D. Sarmento ( UDT ) | 1999 |

|

Administrador |

|

| João de Corte Real Araújo | around 2008 |

| Manuel Pereira | around 2011 |

| Manuel Ramos Pinto | currently (at least since 2014) |

After East Timor's declaration of independence in 1975 , Indonesia began a large-scale invasion of the neighboring country . Maubisse was conquered in January 1976, then a battle broke out over the important Fleixa Pass . It was not until February 23 that the Indonesians reached the town of Ainaro, where they joined forces with troops that had landed in Betano . Ainaro was conquered by the Indonesians on February 23, 1975 . Until October 1976, the towns of Ainaro, Maubisse, Hato-Udo and Zumalai, as well as the most important highways, were under Indonesian control. In the mountains, the population was initially spared from the invaders, while the population in bases de apoio fled from the large towns , such as Catrailete , near the Tatamailau in Ermera, in Mape-Zumalai or the neighboring regions. A large Indonesian military base was built in Ainaro, from where action was taken against the FALINTIL operating in the Ainaros mountains . From September 1977 the Indonesian army began to occupy the region by area, which was completed in February 1978. The resistance bases were destroyed, the residents dispersed or taken prisoner.

Nevertheless, the FALINTIL under Xanana Gusmão , who later became president of the independent East Timor, continued to fight against the occupiers in the mountains of Ainaros. On August 20, 1982, FALINTIL fighters attacked the Koramil in Dare , Koramil and police in Hatu-Builico and the Hansip (civil defense) in Aituto . This was part of the Cabalaki uprising in which several Indonesian bases in the region were attacked at the same time. The Indonesians immediately sent more troops to the region. In Dare houses were burned down, schools closed and women and children were forced to keep watch in military posts. There were also forced relocations, pillage, looting and rape. Military posts were set up in every Aldeia in the region, plus eight community posts around Dare. FALINTIL fighters and much of the population fled the area.

In the event of forced resettlements, the residents of Maubisse were temporarily deported to Aileu, which led to conflicts with the local population who were traditionally hostile to them. In order to better control the occupied territory, in Ainaro, as in other parts of East Timor, pro-Indonesian militias ( Wanra ) were set up to support the military, such as the Mahidi , who were based in Cassa. These militiamen and the Indonesian soldiers stationed in Ainaro committed a large number of crimes during Operation Donner in the vicinity of the independence referendum on August 30, 1999, and ultimately destroyed more than 95% of the buildings in the city of Ainaro. The population in the then sub-districts of Hato-Udo and Hatu-Builico was no better off. Only in Maubisse was the destruction not quite as extensive. Many residents have been displaced and fled to West Timorese refugee camps or into the wilderness. For example 1,200 residents of Mau-Nuno who fled to the woods on August 11th for fear of their lives. Others formed small groups to defend themselves against the militias. It was not until the international intervention force INTERFET ensured that peace and order were restored until East Timor was given independence again in 2002.

Ainaro in independent East Timor

On June 11, 2006, riots broke out in Maubisse. The place was considered a stronghold of the rebellious soldiers under Alfredo Alves Reinado , who at the end of April sparked the worst unrest in East Timor since independence. Street fighting also broke out in Maubisse on November 22nd.

politics

The administrator of Ainaro is appointed by the state government in Dili. In 2003/2008 this was João de Corte Real Araújo , in 2011 Manuel Pereira . The current administrator is Manuel Ramos Pinto (January 2016).

In the elections for the constituent assembly , which later became the national parliament, FRETILIN in Ainaro won the most votes with 27.56%. The direct mandate went to Mário Ferreira (FRETILIN) with 34.63% of the votes. In the 2007 parliamentary elections , the Coligação ASDT / PSD managed to become the strongest force in Ainaro with 29.13% of the vote. In the parliamentary elections in 2012 , the CNRT received the most votes with 37.2%, as well as in 2017 with 30.3%. In the early elections in 2018 , the Aliança para Mudança e Progresso (AMP) , to which the CNRT now belonged, received 57.2% of the vote.

In the first round of the presidential elections in 2007 , Francisco Xavier do Amaral from the Associação Social-Democrata de Timor (ASDT) in Ainaro was able to unite the most votes, but was eliminated in third place nationwide. In the second round in Ainaro, the non-party José Ramos-Horta won with 76.2% . All opposition parties had united against the FRETILIN candidate behind Ramos-Horta. 2012 won Fernando de Araújo in Ainaro, with 39% of votes, but lost again as the nation's fourth place beaten. The second round in Ainaro went to election winner Taur Matan Ruak with 67.2%. In the 2017 presidential elections , António da Conceição of the PD in Liquiçá won the most votes, but only finished second nationwide.

Economy and Infrastructure

| Share of households with ... | ||

| agriculture | ||

| Field crops | Share 2010 | Production 2008 |

| Corn | 74% | 1,221 t |

| rice | 11% | 2,934 t |

| manioc | 58% | 2,604 t |

| coconuts | 27% | not specified |

| vegetables | 53% | 1,732 t (with fruit) |

| coffee | 58% | not specified |

| Livestock | ||

| Livestock | Share 2010 | Number of animals 2010 |

| Chicken | 72% | 32,142 |

| Pigs | 73% | 16,466 |

| Bovine | 17% | 6,435 |

| Water buffalo | 16% | 4,958 |

| Horses | 38% | 6,382 |

| Goats | 24% | 6.317 |

| Sheep | 3% | 1,095 |

| Furnishing | ||

| Furnishing | Share 2010 | Number of households |

| radio | 40% | 3,847 |

| watch TV | 11% | 1,070 |

| Telephone (mobile / landline) | 45% | 4,350 |

| fridge | 2% | 199 |

| bicycle | 5% | 437 |

| motorcycle | 14% | 658 |

| automobile | 2% | 196 |

| boat | 1 % | 84 |

According to the 2010 census, 48% of all residents who are ten years or older work (national average: 42%). 5% are unemployed (5%). 80.0% of households practice arable farming, 86.8% cattle breeding (as of 2010). The mountainous region is rich in water and is one of the most fertile regions in the country. The most important staple food is maize, which is grown by three quarters of households. More than half grow cassava. Other agricultural products include vegetables, fruits, beans, vanilla and olives. Rice is also grown in the southern part of Ainaros. Coffee is grown in the highlands for resale. Almost every third household has coconut palms.

The main animals kept are chickens and pigs (every third household). Horses serve as a means of transport for more than a third of households in the highlands. There are also buffalo, cattle, goats and sheep. There is fishing on the south coast. The former commercial timber industry has been banned since the end of the Indonesian occupation.

The spectacular mountain world has tourist potential. So far this has been limited due to the poor infrastructure. Tourist accommodations are available in Maubisse , Hatu-Builico and Manutaci .

97% of Ainaro's households live in their own home. Only about a sixth of all residential buildings are made of bricks or concrete. Most of the buildings are still made from natural materials such as bamboo or palm fronds. Half of the roofs are made of zinc and iron sheets that aid organizations had distributed after Operation Donner for quick reconstruction. However, over 40% of the houses are still covered with palm fronds or straw. In almost four fifths of the houses the floor is made of tamped clay, only one sixth is made of concrete or tiles. Overall, the natural materials in Ainaro are far more widespread than in other countries. Around 50% of households have access to clean drinking water sources (less than the national average), with only 15% having the water on or in the house. The residents of the other households have to get the drinking water from public pipes, wells, springs or bodies of water. Almost all households use wood for cooking. The national average is less. More than two thirds use petroleum to generate light, only one sixth use electricity. In the national average, half use petroleum and over a third use electricity.

Three highways connect the main towns of Ainaros with each other and with the centers outside the municipality. The A02 comes from Dili in the north, passes Maubisse and Ainaro and turns west at Cassa to the municipality of Cova Lima. The A05 splits off from the A02 at Lientuto and goes south-east to Same (Manufahi municipality). The A13 runs from Cassa as part of the southern coastal road east towards Dai-Sua and Betano (Manufahi municipality). Another main route connects Hatu-Builico with the A02 in the east and another Maubisse with Turiscai in Manufahi. There are other smaller roads and slopes, but they are in very different conditions. In the rainy season, road closures due to flooding, demolitions and landslides are normal. The unpaved roads are then often no longer passable, which is why Timor ponies are still very important as a means of transport. Public transport between the locations is carried out by trucks and minibuses ( microléts ). There are no airfields in Ainaro, if necessary air transport is carried out by helicopters. There are no anchorages on the coast, as is the case in Bonuc , the only coastal town.

There are two municipal radio stations in the municipality of Ainaro. Lian Tatamailau (FM 98.1 MHz) broadcasts from Ainaro and Radio Maubisse Mauloko (FM 89.7 MHz) from Maubisse . The FRETILIN radio station Radio Maetze can be received on FM 97.9 MHz. 40% of households have a radio, 11% a television.

| Share of households with ... | ||||||||

| ... house walls made of ... | ||||||||

| Brick / concrete | Wood | bamboo | Clay | Iron / zinc sheet | Palm fronds | Natural stones | Others | |

| 15% | 5% | 43% | 5% | 3% | 26% | 1 % | 2% | |

| ... roofs made of ... | ... floors made of ... | |||||||

| Palm fronds / straw / bamboo | Iron / zinc sheet | Roof tiles | Others | concrete | Tiles | Soil / loam | Bamboo / wood | Others |

| 44% | 54% | 1 % | 1 % | 11% | 4% | 78% | 4% | 3% |

| Drinking water supply through ... | ||||||||

| Pipe or pump in the house | Line or pump outside | Public pipeline, well, borehole | protected source | unprotected source | Surface water | Others | ||

| 3% | 12% | 18% | 16% | 32% | 16% | 3% | ||

| Energy source for cooking | Light source | |||||||

| electricity | petroleum | Wood | Others | electricity | petroleum | Wood |

Light nut / candle berry |

Others |

| 1 % | 4% | 95% | 1 % | 15% | 76% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

Web links

- Ministry of State Administration and Territorial Management: Ainaro

- District Profile 2012 (tetum, PDF file)

supporting documents

literature

- Geoffrey C. Gunn: History of Timor. Technical University of Lisbon (PDF file; 805 kB)

- Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq: The homeland and expansion of the Bunaq in central Timor. In: Andrew McWilliam, Elizabeth G. Traube: Land and Life in Timor-Leste: Ethnographic Essays. 2011

Web links

- Ainaro District Development Plan 2002/2003 ( Memento from November 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (English, PDF file; 1.16 MB)

- Ministry of State Administration and Territorial Management : Plano Estratégico de Ainaro , January 8, 2016 (tetum) , accessed on May 7, 2016.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Direcção-Geral de Estatística : Results of the 2015 census , accessed on November 23, 2016.

- ↑ Geoffrey Hull : The placenames of East Timor , in: Placenames Australia (ANPS): Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey, June 2006, pp. 6 & 7, ( Memento of February 14, 2017 in the Internet Archive ). September 2014.

- ↑ Plano Estratégico de Ainaro, p. 19.

- ↑ Highlights of the 2010 Census Main Results in Timor-Leste English ( Memento from August 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 4.5 MB)

- ↑ a b c d Direcção Nacional de Estatística: 2010 Census Wall Chart (English) ( Memento from August 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2.7 MB)

- ↑ Plano Estratégico de Ainaro, p. 70.

- ↑ UNTAET Regulation No. 2000/19 - On protected places ( Memento from October 18, 2000 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 39 kB)

- ↑ UNTAET Regulation No. 2000/19 - On protected places ( Memento from October 18, 2000 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 39 kB)

- ^ Government of Timor-Leste: Timor-Leste builds National Park Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão , October 26, 2015 , accessed on November 11, 2015.

- ↑ a b Timor-Leste GIS Portal ( Memento from June 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Plano Estratégico de Ainaro, p. 25.

- ↑ a b Mark O'Shea et al. a .: Herpetological Diversity of Timor-Leste Updates and a Review of species distributions. In: Asian Herpetological Research. 2015, 6 (2): pp. 73-131., Accessed on July 17, 2015.

- ↑ Direcção Nacional de Estatística: Timor-Leste in figures 2011. (PDF; 3.8 MB) Archived from the original on February 19, 2014 ; Retrieved May 5, 2013 .

- ↑ a b Census of Population and Housing Atlas 2004 ( Memento of February 4, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 14 MB)

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 177-178.

- ^ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. Pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Results of the 2010 census for the Suco Mau-Nuno (tetum; PDF; 8.2 MB)

- ↑ a b c d Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq. P. 179.

- ↑ Results of the 2010 census for the Suco Cassa ( Memento of April 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) ( tetum ; PDF; 8.2 MB).

- ↑ District Pritory Tables: Ainaro 2004 ( Memento from November 17, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 20 MB)

- ↑ Ainaro District Development Plan 2002/2003 p. 8

- ↑ Monika Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. A critical study of the Portuguese colonial history in East Timor from 1850 to 1912. pp. 134-136, Abera, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-931567-08-7 , (Abera Network Asia-Pacific 4), (also: Heidelberg, Univ., Diss ., 1994).

- ↑ Dom Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo : 150 Anos da criação de distritos em Timor , Forum Haksesuk, October 27, 2010 , accessed on May 11, 2016.

- ↑ Gunn p. 89.

- ↑ Gunn p. 95.

- ↑ a b Plano Estratégico de Ainaro, p. 17.

- ↑ Gunn p. 97ff.

- ↑ Kisho Tsuchiya: Indigenization of the Pacific War in Timor Island: A Multi-language Study of its Contexts and Impact , p. 13, Journal War & Society, Vol. 38, No. February 1, 2018.

- ↑ a b c AICL Colóquios da Lusofonia: D. ALEIXO CORTE REAL, UM EXEMPLO DE FIDELIDADE E PATRIOTISMO , 23 September 2011 , accessed on 7 May 2018.

- ↑ a b c Kisho Tsuchiya: Indigenization of the Pacific War in Timor Island: A Multi-language Study of its Contexts and Impact , pp. 17-18, Journal War & Society, Vol. 38, No. February 1, 2018.

- ↑ Gunn, p. 121ff.

- ↑ "Part 4: Regime of Occupation" ( Memento of January 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) from the "Chega!" Report of the CAVR (English)

- ↑ "Part 3: The History of the Conflict" (PDF; 1.4 MB) from the "Chega!" Report of the CAVR (English)

- ↑ a b "Chapter 7.3 Forced Displacement and Famine" ( Memento of November 28, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.3 MB) from the "Chega!" Report of the CAVR (English)

- ↑ "Chapter 7.4 Arbitrary detention, torture and ill-treatment" ( Memento from February 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2 MB) from the "Chega!" Report of the CAVR (English)

- ↑ 6.4 Mauchiga case study: a quantitative analysis of violations experienced during counter-Resistance operations ( Memento from February 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 456 kB) from the final report of the Reception, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of East Timor (English)

- ↑ Chapter 7.7: Sexual Violence ( Memento of February 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.2 MB) from the final report of the Reception, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of East Timor (English)

- ^ East Timor Government: East Timor Districts , accessed April 10, 2016.

- ^ New riots in East Timor . In: Blick , June 11, 2006

- ↑ Four believed dead in more Timor violence . ( Memento from March 14, 2007 in the web archive archive.today ) The Australian, November 16, 2006

- ^ Kolimau 2000 Group Attacks Martial Arts Group . ( Memento of September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) UNOTIL, November 17, 2006

- ^ One killed, two injured in fresh E Timor violence . ( Memento of January 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) ABC news, November 22, 2006

- ↑ World Bank: Participation List Timor-Leste and Development Partners Meeting 3-5 December 2003 , accessed April 27, 2020.

- ↑ Despacho Nº .: 74 / MAEOT / 2008 ( Memento of February 3, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Website of the government of East Timor: The population of Hatubuiliku appreciated the NSDP (English)

- ↑ Descentralização Administrativa na República Democrática de Timor-Leste: Ainaro , accessed on February 7, 2014

- ↑ Plano Estratégico de Ainaro, p. 6.

- ↑ Lurdes Silva-Carneiro de Sousa: Some Facts and Comments on the East Timor 2001 Constituent Assembly Election ( Memento of October 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) ( RTF ; 199 kB), pp. 299-311, Lusotopie 2001.

- ↑ CNE - official results on 9th July 2007 ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 118 kB)

- ↑ CNE: CNE 2017

- ↑ CNE: Munisipios , accessed May 30, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Direcção Nacional de Estatística: Suco Report Volume 4 (English) ( Memento from April 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 9.8 MB)

- ↑ a b Direcção Nacional de Estatística: Timor-Leste in Figures 2008 ( Memento from 7 July 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.7 MB)

- ↑ UNMIT: Timor-Leste District Atlas version 02, August 2008 ( Memento from December 3, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 583 kB)

- ^ Road map of East Timor, 2001.

- ↑ ARKTL - Asosiasaun Radio Komunidade Timor-Leste (English)

Coordinates: 8 ° 59 ′ S , 125 ° 30 ′ E