Languages of East Timor

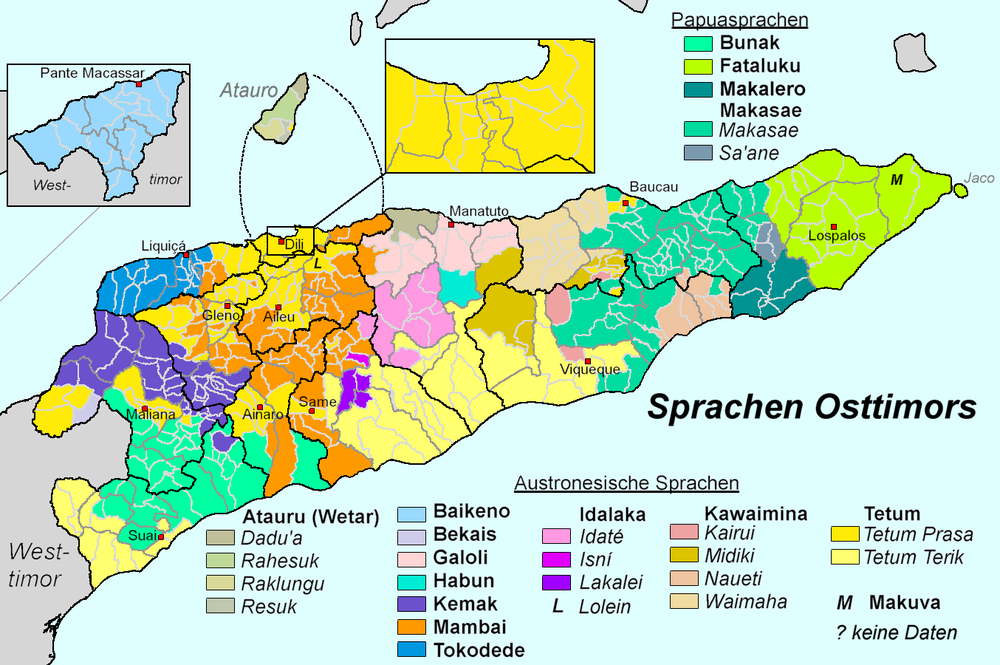

Although the country only has a million people, there are a variety of languages in East Timor . In addition to the long- established Malayo-Polynesian and Papuan languages , several other languages have spread through immigration and conquest over the past 500 years.

Overview

The East Timor constitution distinguishes three categories of the languages of East Timor (number of native speakers as of 2010) .

The official languages are constitutionally the Malayo-Polynesian language Tetum (Tetum Tetun) and Portuguese . 449,085 speak a Tetum dialect as their mother tongue, but only 595 residents speak Portuguese as their mother tongue.

There are also 15 national languages recognized by the constitution (alternative names in brackets) :

-

Malayo-Polynesian languages:

-

Fabronic languages :

- Atauru (Wetar): 8,400 speakers, including the dialects Dadu'a , Rahesuk , Raklungu and Resuk

- Baikeno (Baiqueno, Vaiqueno, Atoni, Dawan, Uab Meto): 62,201 speakers.

- Bekais (Becais, Welaun): 3,887 speakers.

- Galoli (Galóli, Lo'ok, Galole, Galolen, Glolen): 13,066 speakers.

- Habun (Habo): 2,741 speakers.

- Kawaimina (Cauaimina, includes Kairui , Waimaha , Midiki, and Naueti ): 49,096 speakers.

- Makuva (Makuwa, Maku'a, Lovaia, Lovaea): 56 speakers.

- Ramelaic languages :

-

Fabronic languages :

- Papuan languages:

According to Article 159 of the Constitution, Bahasa Indonesia and English are working languages because these languages are still widely spoken. Especially among young people as Portuguese was not allowed during the Indonesian occupation .

The 2010 census also asked about the residents' native language. Since no answers were given to choose from, different names of the languages and dialects were given. The census made no distinction here. In the table below the answers are arranged according to the languages listed in the Constitution. The speakers of Malay and Chinese are also listed. 722 residents call Chinese their mother tongue.

Knowledge of the official and working languages was also asked. Of 741,530 respondents at the 2004 census, 138,027 speak Portuguese and 134,611 can only read it. 599,745 residents speak Tetum, 34,713 can only read it. 66,343 East Timorese speak English, 93,817 can only read it. 808 name English as their mother tongue. In 2010, 36% of the population could speak, read and write Indonesian, another 1% could speak and read, 11% only read and 7% only speak.

Adabe is a Papuan language that is only spoken in Timor and not, as some sources indicate and the alternative name Atauru suggests, on the island of Atauro . The alternative name also leads to confusion with the Austronesian national language of the same name. Adabe has no official status in East Timor. In the 2015 census, 260 people named it as their mother tongue.

history

The diversity of the native languages of East Timor can be explained by the at least three waves of immigration (Veddo-Austronesians, Melanesians and Austronesians), the Timorese settled and the rugged mountains of the island, which often had a dividing effect. The Veddo Austronesians probably reached Timor between 40,000 and 20,000 BC. It is generally assumed that the Melanesians 3000 BC. Immigrated to Timor and from 2500 BC. Were partially ousted by descending Austronesian groups . In the case of the Fataluku, it is now suspected on the basis of recent linguistic research that they might not have reached Timor until after the Austronesians from the east and that they in turn displaced or assimilated them. Such a scenario is also speculated among the Makasae. With the Bunak, however, only place names that are of Papuan origin are found in the heartland, so that the Bunak must have settled here before the Austronesians. Since Bunak shares parts of a non-Austronesian vocabulary with Fataluku, Makasae and Makalero , there must have been a Proto-Timor Papuan language earlier , from which all the Papuan languages of Timor originate.

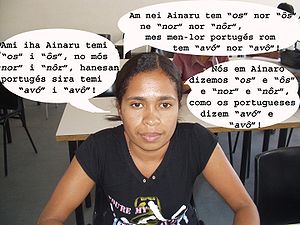

Under Portuguese rule, you could only continue your education in Portuguese, although the Lingua Franca Tetum and the other languages could be used. At the end of the colonial period, around 5% of the population spoke Portuguese. Portuguese had a strong influence on the Tetum dialect Tetun Prasa (Portuguese Tétum-praça ), which was spoken in the state capital Dili , in contrast to the Tetun Terik spoken in the country . Today Tetun Prasa is more widespread and is also taught in schools as the Tétum Oficial .

At the beginning of the 19th century, Malay , the trading language in the eastern part of the Malay Archipelago in Timor, was spoken and used even by the Portuguese and Topasse. Then the language disappeared in Portuguese Timor. Apparently the Portuguese administration took care of this after 1870. Tetum Prasa and Portuguese took over the function of Malay as the language of trade within Timor and abroad. Only among the Arab minority in East Timor did Malay survive as an everyday language and in 1975 in Oe-Cusse Ambeno as a second language. The influence of the surrounding Indonesian West Timor played a role here. But in Oe-Cusse Ambeno of all places, after 16 years of Indonesian occupation, the proportion of Malay / Indonesian-speaking residents was the lowest: 42%. In all of East Timor the average was 60%. 250,000 inhabitants were Indonesian immigrants from Java and Bali . Your mother tongues no longer play a role in today's East Timor. Most of the immigrants left the country with the independence of East Timor.

| Indonesian speaker in 1991 in the districts of East Timor | |

| District | Proportion of Indonesian speakers |

|---|---|

| Aileu | 63.81% |

| Ainaro | 49.81% |

| Baucau | 55.91% |

| Bobonaro | 56.88% |

| Cova Lima | 56.53% |

| Dili | 84.00% |

| Ermera | 55.30% |

| Lautém | 59.97% |

| Liquiçá | 54.33% |

| Manatuto | 68.05% |

| Manufahi | 61.61% |

| Oe-Cusse Ambeno | 42.46% |

| Viqueque | 43.98% |

| total | 60.34% |

The use of Portuguese was prohibited under the Indonesian occupation from 1975 to 1999. The only official language was Bahasa Indonesia, which also replaced the Tetum as the lingua franca for this time. Tetum gained importance when the Vatican approved the language for the liturgy on April 7, 1981 . The result was both a strengthening of the East Timorese's national identity and a further influx of Catholicism.

For many older East Timorese people, Bahasa Indonesia leaves a negative taste, as it is equated with the occupiers, but younger people in particular were suspicious or even hostile towards the reintroduction of Portuguese as the official language. Like the Indonesians in Dutch , they saw it as the language of the colonial rulers. However, the Dutch culture had significantly less influence on Indonesia than the Portuguese in East Timor. The cultures in the eastern part of the island mixed mainly through the marriage of the Portuguese and Timorese. In addition, Portuguese was the working language of the resistance against Indonesia. Young Timorese see Portuguese as a disadvantage and accuse the leaders of their country of favoring people returning to East Timor from overseas. But this is weakened by the fact that older Timorese who were in the resistance and therefore speak Portuguese could not find a job. Many foreign observers, especially from Australia and Southeast Asia , also criticized the reintroduction of Portuguese. Nonetheless, many Australian linguists, for example, worked on the planning for the official language regime, including the introduction of Portuguese. Teachers were sent to East Timor from Portugal and Brazil to teach the population. This turned out to be problematic because the teachers mostly did not know the local languages or cultures. The late Brazilian Sérgio Vieira de Mello , who headed UNTAET and worked closely with the later President of East Timorese Xanana Gusmão , won a lot of respect among the population because he learned Tetum.

Português de Bidau , the Portuguese Creole language of Timor, which had connections with the Malacca Creole , died out in the 1960s. The speakers gradually started using standard Portuguese. Bidau was spoken almost only in the Bidau district in the east of Dilis by the Topasse ethnic group , mestizos with roots from the Flores and Solor region. Macau Creole Portuguese was also spoken in Timor during the heaviest immigration period in the 19th century, but quickly disappeared.

In the last few decades the speakers of the Malayo-Polynesian national language Makuva have been almost completely assimilated by the Papuan language Fataluku. However, Makuva may survive as a secret cult language among some Fataluku clans. Rusenu is already extinct . A linguist only found evidence of this in 2007 in Lautém .

At the beginning of 2012, a heated discussion began about plans by the government and UNESCO to hold classes in the respective national languages in primary schools. According to this, the children should first be taught in their mother tongue and verbally in Tetum in preschool. With the beginning of elementary school, Portuguese follows orally. As soon as the students have mastered their mother tongue in writing (2nd grade), reading and writing should follow in Tetum, later in Portuguese (from 4th grade). This leads to bilingual training in the two official languages, the mother tongue is used for support. Reading skills in the mother tongue should then be further promoted. After all, lessons are only given in the official languages. In the 7th grade, English is added as a foreign language and Bahasa Indonesia as an elective, along with other languages in the 10th grade. While proponents seek to preserve the cultural identity of the country's various ethnolinguistic groups, many perceive the program as a threat to national unity and regionalism.

According to UNESCO, several languages are threatened with extinction in East Timor: Adabe, Habun, Kairui, Makuva, Midiki, Naueti and Waimaha.

distribution

The following maps show the results of the 2010 census. For three sucos the data is missing because the documents cannot be accessed online. When evaluating the information, it should be noted that due to the sometimes very small population figures, individual speakers can make up a measurable proportion in the population of a suco, even if their language is traditionally not spoken there. As a result of the refugee movements and rural exodus in recent decades, native speakers have also moved to other parts of the country. The proportion of immigrants from other communities is particularly high in Dili. In the entire municipality of Dili , the population increased by 12.58% between 2001 and 2004. Almost 80,000 of the residents were born outside of Dilis. Only 54% of the population were born here. 7% were born in Baucau , 5% each in Viqueque and Bobonaro , 4% in Ermera , the rest in the other municipalities or abroad.

Largest language group in the respective Sucos of East Timor according to the results of the census of October 2010. In addition, the two language islands of Lolein (L) and Makuva (M).

- Proportion of native speakers in the sucos of East Timors (2010 census)

literature

- Geoffrey Hull: Timorese Plant Names and their Origins , 2006.

- George Saunders: Tetum for East Timor. Word by word. Reise Know-How Verlag Rump, Bielefeld 2004, ISBN 3-89416-349-6 . (Gibberish Vol. 173).

Web links

- Livru Timor : Books with a Creative Commons license for free download in the languages of East Timor

- Dili Institute of Technology : Center of Language Studies

- Instituto Nacional de Linguística UNIVERSIDADE NACIONAL TIMOR LOROSA'E ( Memento of October 12, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- Dr. Geoffrey Hull : The Languages of East Timor. Some Basic Facts , Instituto Nacional de Linguística, Universidade Nacional de Timor Lorosa'e ( Memento from September 18, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file; 203 kB)

- Languages of Timor Lorosae - part of Ethnologue

- Peneer meselo laa Literatura kidia-laa Timór . The first significant text ever written in Tokodede

- Video for "National Unity Campaign" of UNMIT with different language examples from East Timor

- FEATURE-East Timor drowns in language soup . On the problem of Portuguese as the official language.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Direcção Nacional de Estatística: Population Distribution by Administrative Areas Volume 2 English ( Memento from January 5, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) (Census 2010; PDF; 22 MB)

- ↑ Direcção Nacional de Estatística: Population Distribution by Administrative Areas Volume 3 English ( Memento of October 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (Census 2010; PDF file; 3.38 MB)

- ↑ a b c d e John Hajek: Towards a Language History of East Timor ( Memento of December 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 87 kB), Quaderni del Dipartimento di Linguistica - Università di Firenze 10 (2000): 213- 227

- ^ Population Settlements in East Timor and Indonesia ( Memento of February 2, 1999 in the Internet Archive ) - University of Coimbra

- ↑ a b Andrew McWilliam: Austronesians in linguistic disguise: Fataluku cultural fusion in East Timor ( Memento of November 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 171 kB)

- ↑ Antoinette Schapper: Finding Bunaq: The homeland and expansion of the Bunaq in central Timor ( Memento of October 24, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), pp. 163-186, in: Andrew McWilliam, Elizabeth G. Traube: Land and Life in Timor -Leste: Ethnographic Essays , p. 182, 2011

- ↑ Schapper: Finding Bunaq , pp. 182-183.

- ↑ Herwig Slezak: East Timor twenty years after the Indonesian invasion: A comprehensive review , Master's thesis, September 1995 , p. 18, accessed on January 16, 2019.

- ↑ Australian Department of Defense, Patricia Dexter: Historical Analysis of Population Reactions to Stimuli - A case of East Timor ( Memento of September 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- ↑ Dr. Geoffrey Hull: The Languages of East Timor. Some Basic Facts, Instituto Nacional de Linguística, Universidade Nacional de Timor Lorosa'e.

- ↑ Bruno van Wayenburg: Raadselachtig Rusenu: Taalkundige ontdekt taalgeheimen en secrettalen op East-Timor . VPRO Noorderlicht. April 4, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ↑ Steven Hagers: A forgotten language on East Timor . Kennislink. March 20, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ Ministry of Education and National Education Commission: Mother Tongue-Basemultilingual Education for Timor-Leste National Policy , September 8, 2010

- ↑ UNESCO: Language Atlas , accessed December 21, 2013

- ↑ Census of Population and Housing Atlas 2004

- ↑ Statistical Office of East Timor, results of the 2010 census of the individual sucos ( Memento of January 23, 2012 in the Internet Archive )