Oe-Cusse Ambeno

|

Rejiaun Administrativa Espesiál de Oe-Cusse Ambeno (tetum) Região Administrativa Especial de Oe-Cusse Ambeno (Portuguese) |

||

|

||

|

||

| Data | ||

| Capital | Pante Macassar | |

| surface | 813.62 km² (8.) | |

| Population (2015) | 68,913 (7.) | |

| Population density | 84.70 inh / km² (4.) | |

| Number of households (2015) | 14,345 (6.) | |

| ISO 3166-2: | TL-OE | |

| Administrative offices | Residents | surface |

| Nitibe | 12,273 | 299.50 km² |

| Oesilo | 11,481 | 97.39 km² |

| Pante Macassar | 37,280 | 356.56 km² |

| Passabe | 7,879 | 60.18 km² |

| map | ||

|

||

The Oe-Cusse Ambeno Special Administrative Region ( Portuguese Região Administrativa Especial de Oe-Cusse Ambeno RAEOA, also Oecusse RAEO) is an exclave of East Timor on the north coast of the otherwise Indonesian West Timor . Culturally, economically and also in terms of family there are close ties between Oe-Cusse Ambeno and the rest of West Timor. On the coast of Oe-Cusse Ambenos, the Portuguese were the first Europeans to land on the island of Timor in 1515 . Here they founded Lifau, their first capital of the colony. The Topasse , a mixed European-Malay population from Flores and Solor , built up their power base in the empires that gave them their name, Oecusse and Ambeno . For a long time they controlled the profitable sandalwood and beeswax trade and in 1769 even drove the Portuguese to Dili . Later, the territory of the two empires returned under Portuguese suzerainty and remained so after the Dutch incorporated the surrounding land into their colony of Dutch East Indies . The later resulting Indonesia occupied the exclave as the first area of Portuguese Timor in 1975 , before the great invasion of the rest of East Timor began a few months later. The area largely spared by the guerrilla war of the East Timorese independence movement was destroyed by the Indonesian army and pro-Indonesian militias as a result of the East Timor referendum on independence in 1999 . After three years of UN administration , East Timor became independent and Oe-Cusse Ambeno its westernmost province.

Oe-Cusse Ambeno is granted a special administrative and economic status in the East Timor constitution . In 2014, the authority of the Special Administrative Region Oe-Cusse Ambeno ( Portuguese Autoridade da Região Administrativa Especial de Oe-Cusse Ambeno , ARAEO) was created to implement the special status . In addition, a special zone for social market economy ( tetum Zona Espesial Ekonomiko Sosial no Merkadu , ZEESM) was set up, which also includes the island of Atauro ( municipality of Dili ).

Surname

As is not unusual in East Timor, there are numerous different spellings for the name of the region: Oe-Kusi, Oecusse, Ocussi, Oecússi, Oecussi, Oekussi, Oekusi, Okusi, Oé-Cusse . The spellings with "k" are mostly derived from Tetum or other Austronesian languages . With "c" are spellings that are based on Portuguese . In the meantime, the double name Oecusse-Ambeno (also Oecussi-Ambeno, Ocussi-Ambeno, Oecússi-Ambeno, Oe-Kusi Ambenu ) is used again in official usage instead of Oecusse alone. The exclave is seldom called just Ambeno (Ambenu) , as it was during the Indonesian occupation .

The historical Timorese empire, which occupied most of the territory of today's Special Administrative Region, was called Ambeno and had its centers in Tulaica and Nunuheu . Oecusse is the traditional name of today's capital Pante Macassar and its surroundings. Here was the second traditional empire of the exclave with its seat in Oesono .

"Oecusse" and "Ambeno" were already used as synonyms for the exclave in the Portuguese colonial times. Later the double name Oecusse-Ambeno came up. In the official list of all administrative units of East Timor from 2009, the district at that time is only referred to by its short name "Oecusse". There is no real political division of the Special Administrative Region along the borders of the old empires. "Oe-Cusse Ambeno" is again officially stated in the Ministerial Diploma 16/2017.

The name "Oe-Kusi" comes from the local Baikeno dialect. "Oe" means "water". There are different interpretations for “Kusi”. It is often equated with the name of a certain type of traditional clay jug, which means “Oe-Kusi” roughly means “water jug”. Other sources indicate that Kusi was a native ruler of Ambeno. “Ambenu” also consists of two words. "Ama" or "am" means "father" or "king". "Benu" is the name of two legendary rulers of the region.

geography

Overview

Oe-Cusse Ambeno has an area of 813.62 km². The Special Administrative Region is completely surrounded by Indonesian territory , except in the north, where it borders on the Sawu Sea . The rest of East Timor's territory is 58 kilometers to the east as the crow flies; on the road, the distance is over 70 kilometers. The coastline of Oecusses is about 50 km long, the land border about 300 km. To the east and south is the Indonesian administrative district of North Central Timor . In the far west, Oe-Cusse Ambeno extends to the government district of Kupang . There were still arguments about two border areas with Indonesia until 2019: the Área Cruz ( Passabe administrative office ) and the 1069 hectare Citrana triangle with the town of Naktuka (Nitibe administrative office). In the case of the island of Fatu Sinai , 12 km off the coast of the westernmost point of the Special Administrative Region, East Timor has waived further claims. From Oe-Cusse Ambeno, border crossings at Bobometo (Oesilo administrative office), Sacato ( Pante Macassar administrative office ) and Passabe (Passabe administrative office ) lead to West Timor. However, only Bobometo and Sacato are legal transitions.

Oe-Cusse Ambeno is divided into four administrative offices (Posto Administrativo) with a total of 18 sucos and 63 aldeias . The administrative offices are Nitibe , Oesilo , Pante Macassar and Passabe. The capital Pante Macassar (Pante Makasar, Oecussi) is located in Suco Costa , which is classified as urban and is 281 km west of Dili.

The main river is the Tono . It rises in the Oesilo administrative office and flows into the Sawusee near Lifau . Outside of the rainy season, however, the river falls dry. Aside from the Tonos, the Special Administrative Region consists of a landscape with arid hills from 800 to 900 m high. The northeast Oe-Cusse Ambenos forms the youngest and wildest surface structure of the entire island and is of volcanic origin. Here lies in the administrative office Pante Macassar with 1259 m one of the highest points of Oe-Cusse Ambenos, the Sapu (Fatu Nipane) . In Passabe the land rises continuously and reaches the highest point of the special administrative region at the southwest tip of the administrative office with the Bisae Súnan at 1560 m . Other mountains are the Manoleu ( 1171 m ) in the northwest of Nitibe and the Puas ( 1121 m ) in Passabe. In Oesilo there are several mud volcanoes south of the town of Saben (Suco Bobometo) .

geology

Regionally, the island of Timor is located in the area of the Outer Banda Arch . The Banda arc was created when the Australian and Eurasian plates collided . Since the late Miocene, distal (distant) sediments of the Australian continental margin have been pushed south onto proximal (near-land) rock complexes . Individual rock blocks from the subsurface are attached (aggregated) to existing arch rocks in the course of the subduction processes. The complex fold and thrust belt continues to develop up to the present time, as the Australian plate pushes northwards under the Eurasian plate at an average of 70 millimeters per year. Numerous earthquakes in this region are an expression of these plate tectonic processes . Tectonostratigraphically, Oe-Cusse Ambeno can be subdivided into three units.

The oldest unit that can be genetically assigned to the Australian continental margin unit is formed in Oe-Cusse Ambeno in the south of the Sucos Naimeco by the Triassic Aitutu formation . The light to dark gray, carbonate - clayey alternation is characterized by finely to coarsely stratified rocks in which numerous carbonate and chert nodules as well as numerous fossils are embedded. The hard radiolarian calcilutite , which makes up 80% of the formation, forms rugged cliffs on which only sparse vegetation grows. 15% of the rock of the Aitutu Formation consists of fossil shells and 5% is formed by calcarenites , schill limestones , quartz arenites, radiolarites and rocks with a high content of bitumen .

In the east of Nitibe, limestones of the Dartollu Formation are exposed in some areas , which were formed in the shallow ocean waters of the Australian continental slope in the Eocene . The mostly honey-brown biocalcarenites are formed from a mixture of granular, calcareous skeletal fragments in a matrix of micrite . This rock formation is characterized by the appearance of numerous cave systems that go back to intensive karstification .

A large part of Oe-Cusse Ambenos consists of rocks of the so-called Bobonaro complex. These rocks were formed as a result of the collision of the two continental plates. This allochthonous rock formation is not only found in the nearest East Timorese municipality of Bobonaro , but is also one of the most common rock formations on the entire island. Embedded in a matrix of claystone are chaotically embedded, lithologically extremely different, angular to rounded boulders from older geological formations ( Permian to Lower Miocene ) that were formed on the Australian continental slope. While the predominantly dark, brown and green clay matrix represents the sedimentation in the basin during formation, the rocks, released from the continental slope by submarine earthquakes, were stored in the soft clay matrix. Different types of rock can be distributed very irregularly in the clay matrix. Such formations are genetically referred to as olisthostromes . Violent ground movements and tectonic unrest during the formation of the Olisthostromes from the late Miocene onwards are indicated by the intensive flaking of the rocks and the formation of numerous armor stripes on the embedded boulders ( olistholiths ). The much harder olistholites form more than 90% of the rocks in the region. The size of the stored foreign rock ranges from a few millimeters to 500 meters in diameter.

The most recent deposits can be found at the mouths of the Tono in the center and Noel Besi on the western border, which have been deposited in syn- and post-orogenic sedimentary basins since the Youngest Miocene. This and the coast of Pante Macassar are covered with young alluvial soils (alluvial land). In the north of Pante Macassar and on the western border there are still various areas for which there is no datable geological data.

During a raw material prospecting in 2002, various minerals and natural resources were mapped in Oe-Cusse Ambeno. In Usitaco there are basalt and diorite deposits that are suitable as stone. Various metal deposits can be found on the coast: gold in Nipane , iron in Beneufe and copper in various places . The latter was checked for recycling by a multinational company back in the 1980s. Other usable raw materials in the Special Administrative Region are gypsum , kaolin , limestone , clay, sand , bentonite , marl and gravel . Pante Macassar produces sea salt .

climate

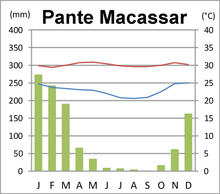

The dry season is between May and November. On the coast, the rain does not start until January. In the rainy season there is heavy rainfall, especially in the highlands, which leads to flooding on the rivers, especially in Citrana and Passabe. During this time Passabe is completely cut off from the outside world. The annual amount of precipitation here is between 2000 and 2500 mm. In Oesilo and Nitibe about 1500 and 2000 mm of rain fall annually, in Pante Macassar it is 1000 to 1500 mm. In the rainy season, the risk of malaria increases. Just one month after the end of the rainy season, the landscape is losing its green color again and withering up. The highest temperatures are measured in November with up to 32.4 ° C, the lowest in July with 22.4 ° C.

fauna and Flora

The native frog world consists mainly of representatives of the rice frogs Fejervarya and a frog that resembles the white-bearded rowing frog ( Polypedates cf. leucomystax ). The black- scarred toad ( Bufo melanostictus ) introduced by humans a few years ago is also numerous . The Timor kite ( Draco timorensis ), which can sail from tree to tree with its flight membranes, is striking . Geckos include the tokeh ( Gekko gecko ), the Asian house gecko ( Hemidactylus frenatus ), the fringed-tailed house gecko ( Hemidactylus platyurus ), the roti house gecko ( Hemidactylus tenkatei ) and an undetermined species of bow-fingered geckos ( Cyrtodactylus ). A scientific expedition in 2010 reported three types of skink in Oe-Cusse Ambeno: an unspecified type of rainbow skink ( Carlia ), multi-striped skink ( Eutropis cf. multifasciata ) and Elbert's emerald skink ( Lamprolepis cf. smaragdina ). In addition, the giant snake reticulated python ( Malayopython reticulatus ) and the sea snake adder flattail ( Laticauda colubrina ) were found. The Timor water python ( Liasis mackloti ) may also be found here.

Two wetlands in Oe-Cusse Ambeno are important for waterfowl and coastal birds: the mouth of the Tono in Lifau with 10 hectares and a marshland near Pante Macassar with 200 hectares. Here, in addition to various types of duck , live little terns ( Sterna albifrons ), reef triele ( Esacus giganteus ), black plover ( Charadrius peronii ) and king spoonbill ( Platalea regia ).

A total of 30.8% of the Special Administrative Region is covered with forest, which is mostly flat dry forest. In the west there are the last remains of original coastal forest. The Suco Beneufe , which rises quickly to an altitude of 300 m , has the greatest variety of deciduous trees in Oe-Cusse Ambeno due to the low population density and poor accessibility. Pterocarpus are most common here . Gyrocarpus americanus can be found in dry places and Corypha utan near water . Hardwoods such as teak can still be found in Bobometo (Oesilo administrative office). 52% of the forest is classified as threatened because of slash and burn and illegal logging. Eucalyptus alba is widespread . The last stocks of the sandalwood tree ( Santalum album ) disappeared during the Indonesian occupation. During this time, the export volume from Oe-Cusse Ambeno increased tenfold compared to that in the Portuguese colonial period.

On the lower reaches of the Tono and a small section of the Noel Besi, the wetlands are used for rice cultivation, the other arable land is mostly in the center of Oe-Cusse Ambenos. There are also smaller savannah areas, the largest south of the capital Pante Macassar.

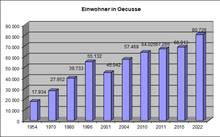

Residents

For 2015, a population of 68,913 is given. In 2011 there were 67,266 inhabitants. Most of them live on the banks of the Tono. The population density in the Special Administrative Region is 84.70 inhabitants / km². At the beginning of 2014, the population was already estimated at 70,350. The population is expected to double by 2025. Between 1990 and 2004 the number of inhabitants grew annually by 1.16%, between 2001 and 2004 even by 8.21%. In 2004 every woman in Passabe had an average of 5.54 children, the number rose to over 5.92 in Pante Macassar and 6.76 in Oesilo, up to 6.88 children per woman in Nitibe (national average 6.99). The infant mortality rate in 2002 in Passabe was 80 deaths per 1000 live births (1996: 78), in Oesilo 115 (133), in Nitibe 119 (137) and in Pante Macassar 122 (119). The national average was 98. Pante Macassar and Passabe are two of 14 subdistricts at the time , in which child mortality rose contrary to the national trend. The average age in Oe-Cusse Ambeno is 18.8 years (2010).

Most of the inhabitants belong to the Atoin Meto (Atoni) , the largest ethnic group in West Timor. In the special administrative region, a distinction is made between the inhabitants of the highlands and the lowlands. The relationship between the groups is mostly peaceful, but tensions come to the fore from time to time. The spoken language is mostly Uab Meto (Dawan) , which is also the most common language in the Indonesian part of West Timor. In 2004, 59.7% named Baikeno , a dialect of Uab Meto, as their mother tongue in Oe-Cusse Ambeno . The Baikeno speakers form the largest population group in the administrative offices of Pante Macassar and Passabe, while the Atoni dialect predominates in Nitibe and Oesilo . However, with this information from censuses, one must take into account that many residents of Oe-Cusse Ambenos use the terms Uab Meto, Baikeno and Dawan as synonyms and make no distinction between language and dialect. In 2015, no distinction was made between the various names in the census, so that 98.1% of Baikeno native speakers were registered. Tetum, Indonesian and Portuguese are also widespread, but only 1.6% of the population name Tetum as their mother tongue, and native speakers of Bahasa Indonesia and Portuguese are a tiny minority. If the second languages are also taken into account, in 2015 54.7% spoke Tetum, 34.5% Bahasa Indonesia, 24.2% Portuguese and 9.6% English .

Anyone who wears European clothing is simply referred to as a malai ("foreigner"), which is also common in other parts of Timor. The terms Kaes muti and Kaes metan are complicated . Kaes actually means “stranger” in Uab Meto, but in Oe-Cusse Ambeno it rather refers to someone who is different and sometimes supreme. A woman can call her husband that, or a villager can call an officer or someone from another village. Muti means "white" and metan means "black". The definitions of who is white and who is black are generally very complex in West Timor. Timorese allies with the Dutch Kaes muti wore white stripes on their clothing, in contrast to the black of the Timorese of Portuguese descent. Black was also the color of Wehales , the ancient cultural center of Timor. White is associated with the outside, black with the inside. In rituals, black is considered attractive, white as repulsive. For example, waving a black cloth is supposed to bring rain, a white cloth stops the precipitation. In Oe-Cusse Ambeno, colors cannot be used to describe skin color. Kaes muti are called non-Timorese, regardless of skin color. When UN forces from Africa and Oceania were in the country after the Indonesian occupation , they too were referred to as white foreigners.

Kaes metan are called in Oe-Cusse Ambeno the inhabitants of the lowlands (sometimes this is also a name), while the highland dwellers see themselves as Atoni. Both groups speak different dialects: Baikeno is spoken on the coast, Atoni in the highlands. The social distinction goes so far that some families in the highlands forbid marrying members of a certain lineage of the Kaes metan . Due to conflicts in the past, this ban was extended to all Kaes metan . Even if Kaes metan move into the mountains, the cultural distinction remains across generations. With the Kaes metan , land and other property are traditionally passed on in the female line, with the youngest being preferred over older children. Up until the previous generation, men always moved to the wife's family after the wedding ( matrilocal ). In the highlands, the oldest child has the privilege, regardless of gender.

The 2010 census found that 99.3% of the population are Catholics and 0.6% Protestants . There were also 36 Hindus , 21 Muslims , 10 followers of the traditional Timorese religion and one Buddhist in Oe-Cusse Ambeno . The 2015 census recorded 99.50% Catholics, 0.39% Protestants, 44 Hindus, 16 Muslims, four Buddhists and no longer any official adherents of the old faith. 12 people gave different information. Every year there is a Good Friday procession (Procissão do Ama Senhor Morto) in Lifau , to which more than a thousand Christians come, including from the Indonesian West Timor. The crucifixion of Jesus is re-enacted in a play.

In contrast to the rest of East Timor, cases of leprosy still occur here , partly because residents reject modern treatment methods. According to the International Leprosy Mission , Oe-Cusse Ambeno had the highest infection rate worldwide in 2003 . Other common diseases are malaria and tuberculosis . In contrast to other regions of Timor, dengue did not occur in Oe-Cusse Ambeno in recent years.

The illiteracy rate in 2015 was 30.3% (women: 31.0%; men: 29.6%), the highest in the country. In 2004 it was 61.9%. In 2015, 34.7% of residents aged three or over attended school. 21.8% had left school. 40.8% have never attended school; the national average is 28.9%. 3.0% of the residents of Oe-Cusse Ambeno only attended pre-school, just under a third only attended primary school. Secondary schools have completed 17.5% of the population. 3.3% have a diploma or a degree, which is less than half the national average. In the Special Administrative Region, 525 teachers and 40 people work in the school administration of the Special Administrative Region. There are 68 primary schools and four secondary schools. Problems are caused by the fact that most teachers do not speak Portuguese. Not many speak Uab Meto either, although there has been a requirement since 2012 that lessons should be in the mother tongue. Most teachers use Tetum or Indonesian.

| Education | Graduation | ||||||||||

| at school | Finished school | never in a school | Preschool | primary school | Pre- secondary |

Secondary | Diploma / University of Applied Sciences |

university | No graduation | ||

| Women | 33.4% | 20.7% | 43.2% | 2.8% | 31.0% | 9.1% | 8.1% | 0.4% | 1.9% | 0.3% | |

| Men | 35.9% | 22.9% | 38.5% | 3.2% | 32.8% | 8.1% | 9.7% | 0.7% | 3.6% | 0.2% | |

| total | 34.7% | 21.8% | 40.8% | 3.0% | 31.9% | 8.6% | 8.9% | 0.5% | 2.8% | 0.3% | |

Culture

Overview

Oe-Cusse Ambeno is considered very traditional. Adat , the old cultural code, has even more influence here than in the regions of East Timor. The mountain region in particular is very isolated. Sometimes there was first contact with the modern world only in the 1950s and in some villages you have never seen a Portuguese or Indonesian official. Even the civil administration of the independent East Timor did not reach the mountain residents until 2003.

Many residents or their ancestors in the lowlands of Oe-Cusse Ambenos only moved from the mountains to the coast a few decades ago. However, the highlands remain the cultural center for these people. Here are ritual houses and holy places like the graves of the ancestors. They return to their region of origin in the mountains for traditional festivities. The festivals include the annual fertility rites, the ritual preparation of the cemeteries, offerings in case of illness or the burying of the umbilical cord of newborns. The festivities fall in the dry months from July to October, when field work comes to a standstill. Weddings in particular take place then, but this time is also used for building a house. Regionally, names, dates and rites at traditional festivals can vary greatly.

A specialty of Oe-Cusse Ambeno is the common food taboo . Depending on the clan affiliation ( kanaf or fama ), certain foods are not eaten, which can affect seafood, coconuts or eggs, and one reason for this is that fishing is underdeveloped here. Basic foods are rice, cornmeal (U-saku) , cassava, sago , sorghum and sweet potatoes. Beans, salads and fruit complete the menu. Meat is almost only eaten on festive occasions. Chewing betel nuts is widespread .

Each clan worships certain plants and animals and has a sacred place where the first ancestors have their graves. The sapu , which unites the clans of a sucos , is ordered over the clan . There are cultural differences between the Sapus in Oe-Cusse Ambeno and the Baikeno dialect of the region also differs in accent from Suco to Suco. Some clans are divided by the border with Indonesia, but keep in touch and carry on their common traditions.

Traditional clothing such as the beti , the woven wraparound skirt for men or tais for women are still everyday clothing today, while this is decreasing in the other regions. The colors and patterns represent the origins of the 18 different sucos. Beit Bose , a special form of the Tais, is only worn by the Liurai (title of the Timorese tribal prince, regionally also called Usif here ). The Beit Bose originally comes from Naimeko , but today it can also be found in other sucos .

Early on in their presence in Timor, the Portuguese gave military ranks to the rulers and other authorities of the various empires. So the ruler of Oe-Cusse Ambeno received the rank of tenente general ( German lieutenant general ). The aim was to integrate them as vassals into a colonial structure and establish hierarchies. Even today, both in East and West Timor, people use inherited honorary titles such as "Cornel" (from Coronel , German colonel ) or "Tenenti" (from Tenente , German lieutenant ). In Oe-Cusse Ambeno this is seldom the case. Use declined after the Portuguese left Oe-Cusse Ambeno to establish their new colonial capital in Dili. The Topasse rulers used the local rank designations.

architecture

Most of the houses in Oe-Cusse Ambeno are simple huts that are still built from materials from nature (see table in the Infrastructure chapter ). The traditional houses have thick, cylindrical roofs made of palm fronds of the Gewang ( Corypha elata ) or the Alang-alang grass ( Imperata cylindrica , German silver hair grass ) . The palm fronds are mainly used on the coast, but also a few kilometers inland, as the grass alone is not particularly suitable as a roofing material. Both materials are used together, especially along the main roads. In the extreme south there are almost only grass roofs, as the transport of palm fronds from the coast is more complex than that of Alang-alang from the highlands. The roof top is partially covered with bark. The roof reaches almost to the ground. Only a low base wall made of clay, branches, bamboo and rocks forms the lower part of the house. Bending down, you enter the house through a small, low wooden door. The rooms in the house are dark, smoky, but spacious. In rural regions, people usually sleep on the floor. Otherwise, beds and baskets of rice or corn are set up along the outer wall. In the center is the hearth with a constantly smoldering fire that blackens the roof inside. In the upper part of the roof, above the fireplace, there are one or two floors where further food supplies are stored. The smoke from the fire keeps bugs and pests away. In contrast to the rest of East Timor, the holy houses of Oe-Cusse Ambeno cannot be distinguished from residential houses from the outside.

Differences between the houses in the Oe-Cusse Ambenos regions are not noticeable to outsiders, but locals can clearly see them from the way the walls are built. One exception concerns the lowlands in the regions that are regularly flooded by the rivers. In the past, houses were built in a pavilion style along the streets . Suspended, woven straw mats served as walls. For the mountain people of Oe-Cusse Ambeno, the former construction is a sign that the flatland inhabitants did not originally come from Oe-Cusse Ambeno. In fact, the rice farmers in the Tono floodplains are mostly descendants of immigrants from southwest Timor and the neighboring islands. In the 1980s, the huts were replaced by houses with solid walls and cement floors.

In the highlands, the parents' house and the children's houses form small hamlets. In the meantime, these often consist of a mixture of traditional and “modern” buildings. In addition to the traditional huts, there are rectangular houses built from a wide variety of materials: brick, cement, clay, stone blocks, wood or bamboo. International aid organizations brought zinc roofs to Oe-Cusse Ambeno between 2001 and 2003 to provide shelter for the many homeless people after the wave of violence in 1999. This has greatly changed the appearance of the highlands. Sometimes you take years to complete these new buildings, also because the material for the walls is missing. They often stand there as a kind of pavilion, only with a roof and cement floor and they are used during the day for weaving or as protection from the sun and rain. If you have the choice, you usually prefer the traditional round huts to the new buildings for sleeping and cooking. They are warmer and the highland people find them more familiar. Whole villages used to consist of individual family clans, but the Indonesian resettlement policy tore these family ties apart. Today, most people settle along the streets without paying attention to living next to their closest relatives if possible.

history

Early and colonial times

| Ruler of the Topasse, later Usif of Oecusse | |

|---|---|

| 1665 † | Simão Luis |

| 1666-1669 | Antonio da Hornay |

| 1670-1673 | Mateus da Costa (from 1671 general captain) |

| 1673 | Manuel da Costa Viera (interim) |

| 1673–1693 † | Antonio da Hornay |

| 1693-1696 | Francisco da Hornay (captain general from 1694) |

| 1697–1722 (?) † | Domingos da Costa |

| 1722-1730 | Francisco da Hornay II |

| 1730-1734 | João Cave |

| 1734–1749 / 1751 † | Gaspar da Costa |

| 1749 / 51-1757 | João da Hornay |

| 1757-1777 |

Francisco da Hornay III. and Domingos da Costa II (at least until 1772) |

| 1782-1796 | Pedro da Hornay (from 1787 again under Portuguese suzerainty) |

| from 1816 | José da Hornay |

| from around 1835 | Filippe da Hornay |

| 1868-1879 | João da Hornay Madeira |

| after 1893-1896 | Domingos da Costa III. |

| after 1898 | Pedro da Costa |

| after 1911-1948 | Hugo Hermenegildo da Costa |

| 1948-1999 | João Hermenegildo da Costa (until 1990) and (from 1949) José Hermenegildo da Costa († November 4, 1999) |

| since 1999 | Antonio da Costa |

Even before the Europeans, Chinese , Malay and Arab traders traded with the inhabitants of Oe-Cusse Ambenos. Place names like Pante Macassar (beach of the Macassars ) or Kolam Cina (Chinese basin) still bear witness to this today. For centuries, the Chinese were the only foreigners who dared to venture into the interior of the island. Otherwise, the traders stayed on the coast in seasonal settlements and waited for the southwest monsoon to return home. Above all, sandalwood and beeswax were popular commodities, for which there were repeated armed conflicts between the region's empires. The sandalwood tree (Santalum album) is therefore called in Uab Meto hau lasi (tree of dispute), hau nitu (devil's tree ) and hau plenat (government tree). Before trading with the outside world, sandalwood, paradoxically, had no particular use for the Timorese. Only the Chinese asked about the sandalwood. As a rule, they asked the Usif for the goods, who commissioned the Naijufs with the delivery and they had the trees procured by the Tobes . Beeswax was important to the Catholic Church. This is how the custom of the ninik-abas (wax-cotton tribute) arose later , which was given to the Usifs of Oecusse and Ambeno before Easter. Much of the wax was then given to the church for Good Friday candles.

A memorial plaque on a replica of Padrão dos Descobrimentos , six kilometers west of today's Pante Macassar, marks the point where Portuguese Dominicans first set foot in Timor on August 18, 1515 . The monument is a symbol of the Special Administrative Region. In November 2015, the Lifau Monument was inaugurated in the form of a replica of a caravel and eight life-size, golden bronze statues. Here the Portuguese founded Lifau in 1556 . This first European settlement on Timor was supposed to secure Portugal's sandalwood trade, while during this time the regional center of the Portuguese was on the neighboring island of Solor. In 1641 the Liurai of Amanuban (Amanubang) , ruler of the area around Lifau, converted to Christianity, had several churches built and formed an alliance with the Portuguese.

In 1642 the Topasse Francisco Fernandes led a Portuguese expedition into the interior of Timor against the previously dominant kingdoms of Sonba'i and Wehale . Fernandes gained dominance in Timor with his victory for Portugal. After that, the immigration of the Topasse (also called black Portuguese ) to Timor increased. The topasses were descendants of Portuguese soldiers, sailors and traders who married women from Solor. They decisively determined the developments on Timor in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Topasse were supported by the Dominicans. The center of Topasse became Lifau, the main base of the Portuguese on Timor. From here the Topasse spread further inland to Kefamenanu and Niki-Niki and founded their own empires, which they ruled as Liurais. Two empires controlled the area of what is now the Special Administrative Region and later gave its name to it: Oecusse on the coast in the northeast of today's exclave and Ambeno in the mountainous west and south. Oecusse was ruled by the Topasse, while Ambeno was ruled by local rulers until the 20th century. Although a Portuguese administrator (captain general) was appointed to the colony in 1642, real power lay with two Topasse family clans who vied for power: the Hornay (Ornai) and the Costa . The Costas still provide the Usif of Oecusse, among other things. The Hornay line is considered to be extinct in Oecusse. But even today, during the Good Friday celebrations in front of the church on the coast of Pante Macassar, next to bamboo pillars (um-uma) with beeswax candles for the Costas and the Cruz (the Ambeno dynasty) one for the Hornays is also set up. Farmers from Suco Lifau also pay a rice distribution to the Hornays. He is now accepted by the ruler of the Costas. A river in Pante Macassar is said to have marked the border between the two families in the past. After the Hornays became extinct, the Costas extended the territory of their empire from Oecusse in the west to Lifau.

In 1663 a Topasse was appointed general captain for the first time. 1701 was Manuel de Santo António by Pope Clement XI. appointed Bishop of Malacca and resided in Lifau until 1722. He is considered the first bishop on Timor. After two governors had previously failed in their attempt to regain control, in 1701 Portugal sent António Coelho Guerreiro (1702 to 1705) again a governor to Timor , who began his service in Lifau on February 20, 1702. The Dominicans were officially released from the administration of the property. Guerreiro remained in office until 1705 before he was expelled from the Topasse. The Portuguese returned to Lifau, but their power remained limited. The Topasse continued to control the sandalwood trade in the interior of the island. Bishop Manuel de Santo António was banished from the island in 1722 by Governor António de Albuquerque Coelho . Two other bishops of Malacca resided in Lifau: António de Castro (1738–1743), who founded Timor's first seminary in Lifau in 1738, and Geraldo de São José (1749–1760), both died in Lifau.

The Topasse saw themselves threatened from several sides: once by Portuguese traders, who received permission from the Crown to take control of the sandalwood trade, and then by the Dominicans, who tried to build their own independent power base in Timor, and also the Local petty kings rebelled regularly, both against Topasse and Portuguese. However, the struggle against the expansion of the Dutch, who had settled in Kupang , on the western tip of Timor, in 1640, united everyone .

|

|

|

|

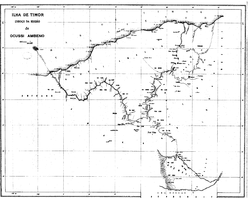

Cards Oe-Cusse Ambeno (1914). On the left map, on which Noimuti is also drawn, Naktuka and Fatu Sinai belong to Portugal. The map is based on the agreement of 1899, on which East Timor's claim to the areas is based. The right map shows the different demarcations of the two colonial powers in Nipane , in the east Oe-Cusse Ambenos.

|

||

When Governor António Moniz de Macedo took office for his second term in 1734, he was greeted surprisingly friendly by the Topasse leader and Capitão-Mor Gaspar da Costa . Gaspar also made it possible to build the first seminary on Timor in Lifau. At that time he resided in Animata , a place with 1,800 huts, a few kilometers south of Lifau, where Portuguese and locals lived. Another alliance between the Portuguese and Topasse came about in 1737, even if there were again unrest in Oecusse in 1741. The Topasse also tried three times to drive the Dutch from Timor. However, when an attack by the Portuguese and Topasse on Kupang in 1749, despite their superior strength, ended in disaster, the rule of both in West Timor collapsed. Many Topasse leaders were killed at the Battle of Penfui (now where Kupangs Airport is located ).

Most of the regional rulers of West Timor concluded an alliance with the Dutch East India Company in the Treaty of Paravicini in 1756 . Some of the resulting Dutch claims were extremely questionable. The contract was also signed by a Nai Kobe as King of Tabenoe (Ambeno is meant) and Sitenomie as King of Liphoa (Lifau). However, both territories were firmly in the hands of the Topasse, allied with the Portuguese. On the other hand, the Portuguese claimed the entire area controlled by the Topasse far into the mountains in the interior of the island, south of Oecusse. This included not only the Noimuti exclave located there , but also regions in which a Portuguese had never set foot before. With an estimated 2,461 km², the area was more than three times the size of today's exclave.

In 1759, Governor Vicento Ferreira de Carvalho (1756 to 1759) decided to give up due to the situation and sell Lifau to the Dutch on his own initiative. When the Dutch wanted to take possession of the place under the German commandant Hans Albrecht von Plüskow in 1760 , they were faced with a Topasse force. From Plüskow was the Topasse rulers Francisco da Hornay III. and António da Costa murdered. To what extent the new Portuguese governor Sebastião de Azevedo e Brito (1759 to 1760) was involved in the defense is stated in the sources contradicting itself.

On August 11, 1769, the Portuguese governor António José Teles de Meneses was forced to leave Lifau at the end of the Cailaco rebellion through the Topasse. Dili became the new capital of the Portuguese on Timor. Even so, the Portuguese flag continued to fly over Oecusse and Ambeno. In 1785, the Topasse ruler Pedro da Hornay again concluded an alliance with the white Portuguese and João Baptista Vieira Godinho , their governor in Dili. Pedro da Hornay was awarded the title of lieutenant general (tenente general) . In 1790 Pedro da Hornay and his brother-in-law, the ruler of Ambeno, once again swore their allegiance on a trip to Dili Portugal. A priest had moved the two rulers to do so.

In 1848 Governor António Olavo Monteiro Tôrres was forced to ask the ruler of Oecusse for help in the fight against rebels. Oecusse then attacked the rebel empire of Balibo. On this occasion, the troops of Oecusses in Janilo (Djenilo) , between Batugade and Oecusse, the Portuguese flag, which in turn called the Dutch on the scene, who feared that the river port of Atapupu would lose its connection with the interior. Negotiations to settle the border disputes were unsuccessful. At the same time rulers of Pantar and Alor complained that Oecusses rulers would intervene in internal conflicts on the neighboring islands and claim them for Portugal. Tôrres revoked these claims.

It was not until 1859 that the island was contractually divided between the two colonial powers into a Dutch western part and a Portuguese eastern part and Oecusse also officially came under Portuguese control (see Treaty of Lisbon ) . In 1863 the area was declared the eleventh military command of Portuguese Timor as Oecussi . Now that the conflict with the Dutch was largely resolved, Portugal was able to use its forces to expand control over the local rulers. This led to numerous uprisings in Portuguese Timor between 1860 and 1912 . During the rebellion in Cová (1868–1871), Oecusse and Ambeno supported the Portuguese. However, the two empires had not paid tribute or taxes to the Portuguese colonial administration since 1861. Only at the instigation of the missionary Francisco Xavier de Mello did Oecusse and Ambeno send representatives to Dili in August 1879 to renew the oath of allegiance. The two princes (principaes) Domingos da Costa and Alexandre Hornay dos Santos Cruz came from Oecusse because the ruler João da Hornay Madeira was too sick to travel. The ruler Pedro Paulo dos Santos Cruz came from Ambeno , along with five princes. The Portuguese gave the ruler of Oecusse the title rei ( German king ), while Pedro Paulo dos Santos Cruz got the subordinate title coronel rei ( German roughly king colonel ). The colonial power made the hierarchy between the two domains in the exclave clear. The princes and other dignitaries Oecusses and Ambenos received further military titles.

At the beginning of the 1880s, Fatumasi (in today's municipality of Liquiçá ) belonged to the empire of Oecusse as an enclave in the kingdom of Motael and produced a lot of coffee.

Troop support from Oecusses and Ambenos to Portugal in the Manufahi War (1896) and other conflicts were one of the reasons why Governor José Celestino da Silva (1894–1908) abandoned the idea of exchanging the exclave for the port of Atapupu. Nevertheless, the two empires still had a reputation for questionable trustworthiness among the Portuguese in the 1880s. In fact, in May 1912, during the great Manufahi rebellion, there was also an uprising against the colonial rulers in Ambeno. All Portuguese in the empire who were not church members were brought to the seat of government by João da Cruz, Usif of Ambeno, and executed. Oecusses ruler Hugo Hermenegildo da Costa , who remained loyal to Portugal, had to leave his empire at that time. The gunboat Pátria brought African soldiers and 150 Moradores stationed in Timor to Ambeno under the command of Capitão Pimenta de Castro. The rebellion was put down, including the destruction of the church of Oecusse. João da Cruz fled to the Dutch part of Timor and Nunuheu lost his status as the seat of the ruler of Ambeno. João da Cruz's relatives, newly appointed by the Portuguese, settled in Tulaica. In addition, the kingdom of Ambeno was now finally subordinated to the kingdom of Oecusse and Hugo da Costa. Many of the Naijufs involved in the rebellion also fled to Dutch Timor. The Portuguese replaced Chefes de Suco , who swore allegiance to the Portuguese state. The result is that there are two Naijufs in some villages. It is controversial what the trigger for the rebellion was. On the one hand, he is associated with the Manufahi rebellion and the rebellion against poll tax and forced labor. Locals today point to traditional rulers who were disadvantaged when the new colonial administrative structure was introduced and therefore revolted. The then Portuguese chronicler Jaime do Inso , however, speaks of the old rivalry between Costas and Hornays, which escalated again here.

The demarcation between the colonial powers continued to be controversial. In 1899 armed clashes broke out between the locals on both sides of the eastern border to Tunbaba , where there were still abundant sandalwood deposits . In addition, the ruler claimed Oecusses the Bikomistreifen (Bicome) in the southeast, to connect to the enclave Noimuti to provide. Offers from the Netherlands to buy Oecusse were rejected by the Portuguese. In the treaty of 1904 the Dutch were assured of the disputed areas in Tunbaba and the acquisition of Noimuti and the Bikomi Strip as soon as the borders of Oecusses were defined. In 1913 the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague was finally called upon to resolve the dispute. In principle, both colonial and local representatives were asked about the drawing of boundaries. However, since the inner Timorese disputes were viewed as too full of conflict, the court of arbitration oriented itself to the existing colonial circumstances. The result was that a later military administrator reported that the border was of no great concern to the local population, as friends and relatives of the people of Oecusses often lived in the areas ceded to the Netherlands.

The final border between the Dutch and the Portuguese was contractually established in The Hague in 1916 . Oecusse and Ambeno were already separated from east Timor by the Treaty of Paravicini. Now the Portuguese exclave Noimuti, south of Oe-Cusse Ambeno, has been exchanged for the Dutch possession of Maucatar .

In 1926, in view of the dwindling stocks, Portugal issued a ban on the trade in sandalwood, but in 1929 the Portuguese eased the ban on the Oe-Cusse Ambeno exclave. It had simply been impossible to monitor compliance here. The trees were illegally felled and simply smuggled overland into West Timor, the Netherlands. Therefore, locals were allowed to fell mature trees, only young trees and their roots remained under protection. The stocks continued to decline

During the Second World War , the Japanese occupied the entire island between 1942 and 1945. Although the Portuguese landed in Timor for the first time in this region, it was a few remote villages in the Oe-Cusse Ambenos mountains that were the last to come into contact with the Europeans in Timor. Europeans first came to some mountain villages in the 1950s. At that time, the priest Norberto Parada began missionary work in the mountains, for the first time with the help of local missionaries. At that time the colonial administrator of Nitibe only ventured into this “wild” region with six to ten armed guards.

In the 1960s, the Bobos and Mekos clans from Usitasae migrated to Lifau due to overpopulation. During this time, residents of the Indonesian village of Manusasi ( West Miomaffo District , North Central Timor Governorate ) began to lay claim to the Bisae Súnan and the fertile area northeast of it. The residents of Haemnanu opposed this. The conflict escalated. In 1965, Portuguese police officers killed an Indonesian as a result. The dispute over the area smoldered to this day.

In December 1966 there were clashes between Indonesian and Portuguese armed forces. The Indonesians burned down some villages in Oe-Cusse Ambeno and shot at the Portuguese territory with mortars. Only the quick reaction of the Portuguese army seems to have deterred the Indonesian troops from further attacks.

In August 1973, the Oecusse military command was transformed into the district (conselho) Oecussi-Ambeno .

Indonesian occupation

In the turmoil of the final months of Portuguese rule over East Timor, Indonesia occupied Oe-Cusse Ambeno on June 6, 1975. The soldiers were disguised as fighters of the UDT who were in conflict with the dominant party FRETILIN . In October, the invasion of the East Timorese border regions of Bobonaro and Cova Lima followed . When FRETILIN finally declared East Timor independent from Portugal on November 28, 1975 , the Indonesian flag was raised in Pante Macassar the next day . The invasion of the rest of East Timor began on December 7, 1975. During the Indonesian occupation, Oe-Cusse Ambeno remained part of the province of East Timor ( Timor Timur in Indonesian ) as Kabupaten . At the beginning of the 1980s, part of the population was forcibly relocated from the mountainous interior, where they traditionally lived due to heat, malaria and raids from the sea, to the coast between Citrana and Sacato , which had been largely uninhabited until then. Only on the banks of the Tonos were there the lowland dwellers who were culturally different from the mountain dwellers and who cultivated rice in the flood zones. After all, the region was spared the fighting of the War of Independence. There were no fighting units of the East Timorese FALINTIL in Oecussi-Ambeno, but there was a wide network of resistance. While the administrative management continued to take place via Dili, the goods traffic now ran via the neighboring towns of Wini , Kefamenanu and Kupang in the Indonesian part of West Timor. The sandalwood stocks, which in contrast to most other areas of Timor still existed here in 1975, mostly disappeared in the first years of the Indonesian occupation. At least there has been progress in education, infrastructure and health programs and the movement of goods and people to West Timor has been made easier.

|

District President (Bupati) |

|

|---|---|

| Jaime dos Remedias Oliveri ( UDT ) | May 1975-1984 |

| Lieutenant Colonel Imam Sujuti (military) | 1984-1989 |

| Vicente Tilman PD ( APODETI ) | 1989-1994 |

| Filomeno Sequeira (APODETI) | 1994-1999 |

In the 1999 independence referendum , the people of East Timor opted for complete independence from Indonesia. A final wave of violence followed by Indonesian security forces and pro-Indonesian militias . Around September 18, 1999, houses were set on fire at random. Only Citrana, Bebo , Baocnana (Nitibe administrative office), Mahata (Pante Macassar) and Passabe were spared . The Sakunar militia and the Indonesian army carried out several massacres of the population, the most momentous in Tumin and Passabe. 4,500 residents were forcibly deported to Indonesia on trucks. 10,000 people fled to the mountains.

At the end of September 5,000 refugees gathered in a camp in Cutete . The American pastor Richard Daschbach has been running the Topu Honis Kutet children's home here since 1988 and was previously a priest in Lelaufe . In his work he had earned the reputation of having great lulik (magic), which is why the people here hoped for protection from the militias. But on September 23, the Sakunar attacked Cutete. The accommodations were burned down, two people were shot and the refugees were driven away. The 14-year-old Fredolino José Landos da Cruz Buno Sila (Lafu) was then sent off by supporters of the Cutete independence movement to get help. A letter to the UN mission in East Timor was hidden in the soles of his flip-flops . The boy crossed the Indonesian West Timor on foot and finally reached an Australian post of the international intervention force INTERFET on the border between West Timor and Bobonaro. Lafu was brought to Dili by helicopter, where he could deliver his message. However, INTERFET did not immediately send soldiers to Oe-Cusse Ambeno, but taught the boy how to operate a radio. Then he was dropped off on the beach at Pante Macassar, where most of the refugees had gathered and were besieged by the militia. When the situation became precarious, Lafu notified INTERFET by radio that the militia attack was imminent. The next morning INTERFET soldiers landed in Pante Macassar with helicopters. Daschbach continued his work in Oe-Cusse Ambeno in the later years.

From October 23, INTERFET again ensured peace and order in Oecussi-Ambeno on behalf of the United Nations . On December 20, UN workers found mass graves of victims of violence. In total, at least 164 people were murdered by the militias in the East Timorese exclave. There were also many deaths due to the flight of the civilian population. 90% of the houses in Oecussi-Ambeno were destroyed, as was the rest of the infrastructure. Some of the destruction was more serious than in other parts of the country, also because INTERFET intervened here later. Many militiamen who had withdrawn from other parts of East Timor before INTERFET came to Oe-Cusse Ambeno and joined the Sakunar here.

Independent East Timor

In 2002, East Timor became an independent state with Oe-Cusse Ambeno as an exclave. UN troops from Australia, New Zealand , Fiji and, until 2003, from Japan and South Korea supported the new administration in the then district . There were also international military observers from the United Nations (UNMO) who monitored the border with Indonesia. After their departure, only the East Timorese National Police and their border unit Unidade da Polícia de Fronteiras ensure security in Oe-Cusse Ambeno. Soldiers from the Defense Forces of East Timor are not stationed here.

In the disputed area of Naktuka with Indonesia , there have been repeated incidents with the Indonesian army since independence. In September 2009, a group of Indonesian soldiers drove to the East Timorese village of Naktuka and began taking photos of newly constructed buildings. They were thrown out by the residents and sent back across the border. On May 26, 2010, 28 armed soldiers from the Indonesian armed forces broke into Beneufe and raised their flags in Naktuka , one kilometer from the border. On May 29, 2010, they destroyed the two houses of two social institutions in Suco. On June 24, an armed unit of the Indonesian army again entered the Naktuka area one kilometer, but withdrew when they encountered a unit of the East Timorese border police. Residents see a connection with the unclear demarcation between the countries. This was the worst incident between the two countries since East Timor's independence in 2002. On March 4, 2011, Indonesian soldiers violated the border again and drove residents from the disputed strip of land. On October 28, 2011, Indonesian soldiers shot at East Timorese who had illegally crossed the border in a car. At the end of 2012, Fisen Falo, a Lian Nain , was found murdered in Naktuka. Some houses are also said to have been burned down by strangers. According to press reports, he was kidnapped by strangers while working in the fields and tortured to death. Indonesian soldiers were rumored to be suspected. Francisco da Costa Guterres , East Timor's Secretary of State for Security, dispatched an investigation team. The border was closed in the area for the time being.

politics

Regional administration

In Article 71 of the East Timorese Constitution, point 2:

"Oe-Cusse Ambeno rege-se por uma política administrativa e um regime económico especiais."

"For Oe-Cusse Ambeno a special regulation applies to administration and business."

The first few years, however, lacked the actual implementation of this constitutional article. In the I (2002–2006), II. (2006–2007) and IV. East Timor governments (2007–2012) there was a separate State Secretary for Oe-Cusse Ambeno. As in the other districts of East Timor at that time, the district administrator was appointed by the national government , as were the administrators of the sub-districts. With the law 03/2014 of June 18, 2014, the Autoridade da Região Administrativa Especial de Oecusse (ARAEO) was created. Marí Alkatiri , General Secretary of FRETILIN and former Prime Minister , was appointed President of ARAEO on July 25th. The appointment was made by President Taur Matan Ruak , on the proposal of Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão .

On January 23, 2015, the Fifth Constitutional Government of East Timor decided at a special meeting in Pante Makassar to transfer powers to Alkatiri in order to comply with the special constitutional status of Oe-Cusse Ambenos. The ceremonial delivery took place on January 25th. Also at the meeting, three new members of the ARAEO were appointed by the cabinet. Arsénio Paixão Bano comes from Oe-Cusse Ambeno. The former minister for “Labor and Solidarity” is vice-chairman of FRETILIN. Leónia da Costa Monteiro from the municipality of Manatuto was Central Finance Officer in the State Secretariat for Security in 2003 . Pedro de Sousa Xavier was formerly Director of the National Directorate for Land and Property ( Portuguese Director Nacional de Terras e Propriedades Timor-Leste DNTP), which reports to the Ministry of Justice .

The other members of the authority were proposed by President Alkatiri and approved by Government Resolution No. 21/2015 appointed on May 19, 2015. In the state budget for 2015, 81.93 million US dollars are earmarked for the special administrative zone Oe-Cusse Ambeno and the special trade zones Oe-Cusse Ambeno and Atauro in order to enable the economy and the development of the basic infrastructure .

In 2017 Alkatiri became Prime Minister of East Timor and was replaced by Arsénio Bano as President of the regional authority. After being voted out of office in 2018 as head of government, Alkatiri returned to head of ARAEO and ZEESM.

Alkatiri's term of office ends on July 25, 2019. On July 8, 34 members of parliament voted , without dissenting, for the amendment of Law 3/2014 on the Oe-Cusse Ambeno Special Administrative Region. This withdrew the President's participation in the appointment of those responsible in the authority. The president of the authority is now appointed by the government by resolution for a maximum of twice five years. The FRETILIN MPs left Parliament at the beginning of the discussion, those of the PD right before the vote. With the change in the law, President Francisco Guterres should be deprived of the opportunity to block the removal of his fellow party member Alkatiri. On July 12th, Guterres demonstratively received the traditional dignitaries Oe-Cussi Ambenos as representatives of the Atoni people, who urged him to prevent the law from being changed and to grant Alkatiri another term of office. Alkatiri finally decided not to extend his term of office and Arsénio Bano was again interim president of ARAEO and ZEESM. On November 6, 2019, the East Timorese Council of Ministers nominated José Luís Guterres as the new President. After criticism of his administration and the shift in the balance of power in the 8th government in favor of FRETILIN, José Luís Guterres was dismissed as president on June 10, 2020. Guterres had not appointed members of the regional government within seven months. It was also criticized that he spent a lot of time out of town. The appointment of various advisors was also commented negatively. On June 12th, Arsénio Bano was officially appointed President of the Palestinian Authority.

In 2014, the districts across East Timor were transformed into "parishes" and the sub-districts into "administrative offices". Oe-Cusse Ambeno received the designation "Special Administrative Region" according to a special status.

|

Administrador |

||

| Francisco Xavier Marques | around 2003 and 2005 | |

|

José Anuno | 2007-2013 |

|

Salvador da Cruz | around 2014 |

|

José Anuno | around 2015 |

|

Presidente |

||

|

Marí Alkatiri | 2014–2017, 2018–2019 |

|

Arsénio Bano | 2017–2018, 2019 |

|

José Luís Guterres | 2019-2020 |

|

Arsénio Bano | since 2020 |

Status 2005:

- District Administrator: Francisco Xavier Marques

- Vice District Administrator: Francisco Bano

- District Development Officer: Domingos Maniquin

- Head of Education: Venancio Lafu

- Head of the health department: Manuel da Cunha

- Head of the Department of Agriculture: José Oki

- District Police Commander: Mateus Mendes

- Pante Macassar Sub-District Administrator: Jose "Camada" Martins

- Administrator of the Oesilo sub-district: Lamberto Punef

- Passabe Sub-District Administrator: Adelino Cau

- Nitibe Sub-District Administrator: Miguel Busan

- Chef Emnasi: António Bobo

2007 to 2013:

- District Administrator : José Tanesib Anuno

Status 2014:

- District Administrator: Salvador da Cruz

Status 2015:

- District Administrator: José Tanesib Anuno

- Assistant District Administrator: Francisco Bano

- Administrator of the Pante Macassar Administration Office: Gonçalo Eko

- Administrator of the Oesilo Administrative Office: Alberto Punef Nini

- Administrator of the Passabe Administrative Office:?

- Administrator of the Nitibe Administration Office: Eurico C. Babo

- President of ARAEO: Marí Alkatiri

- Members of the ARAEO:

- Regional Secretary for Education and Social Solidarity: Arsénio Paixão Bano

- Regional Secretary for Finance: Leónia da Costa Monteiro

- Regional Secretary for Land Planning and Cadastral: Pedro de Sousa Xavier

- Regional Secretary for Administration: Francisco Xavier Marques

- Regional Secretary for Agriculture and Rural Development: Régio Servantes Romeia da Cruz Salu

- Regional Secretary for Health: Lusia Taeki

- Regional Secretary for Municipal Tourism: Inácia da Conceição Teixeira

2017-2018, 2019:

- President of ARAEO: Arsénio Bano

2018-2019:

- President of ARAEO: Marí Alkatiri

- Deputy: Leónia da Costa Monteiro

since 2019

- President of ARAEO: José Luís Guterres

since 2020 President Bano was appointed on June 12, 2020. His regional secretaries received the appointment on July 27th.

- President of ARAEO: Arsénio Bano

- Regional Secretary for Education and Social Solidarity: Avelina da Costa

- Regional Secretary for Finance: Elisa Manequim

- Regional Secretary for Land and Property: António Hermenegildo da Costa

- Regional Secretary for Administrative Affairs: Martinho Abani Elu

- Regional Secretary for Agriculture: José Eta

- Regional Secretary for Health: Manuel da Costa

- Regional Secretary for Trade and Industry: Pedro da Cunha da Silva

- Deputy Regional Secretary for Institutional Strengthening: Leónia da Costa Monteiro

- Deputy Regional Secretary for Social Affairs: Maximiano Neno

Traditional ruling structures

The Liurai ( called Usif here ) is a traditional ruler who officially no longer has power, but is still a person of great respect and influence today. His office is inherited. There are several liurais, but each has a different status.

Two Usif are the traditional rulers in the Special Administrative Region who still have a strong influence. The Usif from Oecusse come from the Topasse family of Costa . Only to them the dynasty of the Usif of Ambeno, called Cruz , is subordinate . In addition to the Usif , the Tobe , the traditional ritual chief, who is an authority over the land, the forest and the water, is also of great importance . The traditional village chief is called Naijuf . Even today dignitaries of the various villages bring tributes to the seat of the Costas in Oesono (Suco Costa) and to the ruler's seat of Ambeno in Tulaica (Suco Lifau) in the pre-Easter period . In some cases tribute payments are even made to Ambeno by villages in the Indonesian part of West Timor. There are certainly voices calling for a stronger role for the monarchs in the Oe-Cusse Ambeno of independent East Timor.

The Costa retinue consists mainly of Kaes metan , lowland dwellers . The Ajantis , servants and palace guards, are alternated annually by four individuals from Cunha and Lalisuk. The family of the Costas themselves are considered to be black Portuguese , who gained their legitimacy through centuries of marriage into the local ruling families .

- Usif of Oecusse: António da Costa

- Usif of Ambeno: Carlos da Cruz

National elections

In the elections to the constituent assembly , from which the national parliament later emerged, FRETILIN in Oe-Cusse Ambeno received the most votes with 38.60%, as it did nationwide. The direct mandate at the time went to António da Costa Lelan , an independent candidate. He was the only one in the country who did not belong to FRETILIN. This had not put up a candidate of its own in Oe-Cusse Ambeno, but Costa Lelan supported the party. In the parliamentary elections in 2007 , FRETILIN in Oe-Cusse Ambeno lost a lot and only got 27.2%. The strongest party was now the Congresso Nacional da Reconstrução Timorense (CNRT) with 34.2%. In the parliamentary elections in 2012 , the CNRT received 39.0% and the FRETILIN only 18.6%. In 2017 , FRETILIN became the strongest force with 39.3%. The CNRT received 29.3%. In the early elections in 2018 , FRETILIN had to accept such heavy losses that the party suspected election fraud, which was rejected by the Tribunal de Recurso de Timor-Leste . The FRETILIN only got 28.4% (more than 3000 votes less), while the Aliança para Mudança e Progresso (AMP) , to which the CNRT now belonged, got over 58.9%. The local FRETILIN boss Arsénio Bano took personal responsibility and apologized publicly on Facebook.

In the presidential elections in Oe-Cusse Ambeno, Fernando de Araújo of the Partido Democrático (PD) won the most votes in the first ballot . But he retired as third nationwide. In the runoff election, the independent José Ramos-Horta prevailed against the FRETILIN candidate Francisco Guterres in both Oe-Cusse Ambeno and East Timor . In 2012 , the later election winner Taur Matan Ruak received the most votes in the first ballot, as well as in the second ballot with 75.92%. In the 2017 presidential elections , António da Conceição from the PD in Oe-Cusse Ambeno, just ahead of the election winner Francisco Guterres from FRETILIN, won the most votes.

Symbols

The profile of the district Oecusse from 2012 of the Direksaun Nacional Administrasaun Local names the monument commemorating the first landing of the Portuguese in Lifau as the symbol Oecusses. It is modeled on a padrão , a stone pillar with which the Portuguese sailors documented the claims of ownership of newly discovered areas for the Portuguese crown.

With the creation of the ARAEO special administrative region and the ZEESM special zone for social market economy, two logos were introduced. In the office of President Alkatiri, in addition to the national flag of East Timor, there is also a flag with the ARAEO logo on a green background and a white flag with the green letters of ZEESM.

Economy and Infrastructure

Oe-Cusse Ambeno's economy is characterized by agriculture and animal husbandry. The household budget is improved only to a small extent by weaving, pottery, baking, small shops and salt extraction.

Agriculture

| Share of households in 2010 in administrative offices with ... | ||

| Administrative office | agriculture | Livestock |

| Nitibe | 78.1% | 74.5% |

| Oesilo | 86.2% | 87.8% |

| Pante Macassar | 82.7% | 86.5% |

| Passabe | 95.6% | 94.2% |

| Share of households with ... | ||

| agriculture | ||

| Field crops | Share 2010 | Production 2008 |

| Corn | 81.3% | 15,232 t |

| rice | 78.0% | 8,994 t |

| manioc | 70.6% | 4,452 t |

| coconuts | 72.0% | - |

| vegetables | 68.6% | 449 t (with fruit) |

| Fruit (temporary) | 72.0% | - |

| Fruit (permanent) | 68.5% | - |

| coffee | 19.9% | - |

| Livestock | ||

| Livestock | Share 2010 | number |

| Chicken | 73.8% | 46.158 |

| Pigs | 72.1% | 25.004 |

| Bovine | 48.3% | 16,562 |

| Water buffalo | 3.8% | 1,791 |

| Horses | 5.0% | 1,372 |

| Goats | 36.4% | 13,344 |

| Sheep | 1 % | 1,027 |

| Furnishing | ||

| Furnishing | Share 2010 | Number of households |

| radio | 23% | 3,192 |

| watch TV | 11% | 1,538 |

| Telephone (mobile / landline) | 24% | 3,332 |

| fridge | 3% | 425 |

| bicycle | 9% | 1,235 |

| motorcycle | 10% | 1,454 |

| automobile | 2% | 239 |

| boat | 2% | 319 |

According to the 2010 census, 46% of all residents who are ten years or older work, 4% are unemployed. 84.0% of households practice arable farming, 85.4% cattle, with agriculture being practiced least often in Nitibe and most frequently in Passabe (status: 2010). Four fifths of households in the Special Administrative Region grow rice. Most of the harvest comes from the growing areas on the banks of the Tono in Lifau and Padiae . Corn, cassava and coconuts are also frequently grown food crops. More than two thirds of households grow vegetables such as sweet potatoes, beans, soybeans, peanuts and various pumpkins. Betel, tobacco, tomatoes, shallots, garlic and salads are also grown for trade. In no other region of East Timor do so many households plant crops and livestock is also practiced here more than average. Usually this is for self-sufficiency. Only coffee is grown much less often in Oe-Cusse Ambeno. Only a fifth of households have coffee plants. Almost half of it is in the southern, high-altitude Passabe administrative office, where 67% of households grow coffee.

Slash and burn is widespread, in which the fields are changed annually. It is harvested once a year between March and May. The new field is then selected in June and cleared of vegetation in September or October. It is then dried out due to lack of rain and easy to burn down. Tree stumps are slowly levered out of the ground with long poles. After the first rain in November to January, plants are planted and weed once or twice at the height of the rainy season. Wild monkeys and birds endanger the harvest and can plunder entire fields. The field work is carried out jointly by men and women. The irrigation systems in the Special Administrative Region have a total length of 140 kilometers and supply the fields of 5000 families. Although the majority of the plants are owned by the government or local communities, mismanagement means that, given the amounts of water and fertile land, the crop yields are below the possibilities. Between October / November and the harvest from March onwards, there is a food shortage in most of the villages in the Special Administrative Region because the harvest from the previous year is insufficient. Three fifths of children under the age of five suffer from constant malnutrition. There is also a lack of proteins and vitamins in the daily diet. Famine loomed in early 2010 when a drought led to crop failures. Most families try to get extra food by gathering wild plants. For this you wild beans (coto, ipe) , Palmfarnsamen (peta) , sago, tamarind and others. After all, the supply situation for the population has improved in the last few decades to the extent that food can be supplied on the markets. A large part of the staple food, such as sugar, rice, flour, cooking oil or noodles, is imported from Dili or Indonesia, which increases prices noticeably. The import tax for everyday necessities from Indonesia alone is 5%. Prices continue to rise when the goods are brought to the administrative offices outside Pante Macassar.

Since 2008 cattle breeding has been in decline. In 2008 they still operated 65% of households, in 2010 it was less than half. The number of animals fell by a third from 25,089. The Cooperativa Café Timor (CCT) has been working on a cattle breeding program since 2009. It organizes the purchase and export of around a third of the fattened cattle and buffalo to Indonesia. Before that, the breeders worked independently. Several cooperatives are also active, for example, in the field of fishing and weaving of tais . Three quarters of households keep chickens and almost as many pigs, which is not uncommon for East Timor. In comparison, the proportion of households with goat husbandry is relatively high, while water buffalo and sheep hardly play a role. 5% of households in Oe-Cusse Ambeno keep horses , which in view of the road conditions still have their right to exist as a means of transport in the Special Administrative Region. Fishing plays only a minor role.

Industry

In Naimeco there is a quarry and an asphalt mixing plant . In Cunha there are other rock deposits that are suitable as building materials. Construction sand can be found in Kinloki . There are also some cement brick factories, rice mills, carpentry shops and tais are woven in homework . But there is often a lack of investment capital and a trained workforce. Added to this is the dependence on deliveries of raw materials and raw materials from Dili or Indonesia. Even so, there are around 600 companies in Oe-Cusse Ambeno, more than half of them micro-businesses and mostly in Pante Macassar.

A special zone for social market economy (ZEESM) is planned on 107 to 300 hectares in the Sucos Costa and Nipane (administrative office Pante Macassar) . Companies are to settle here near the seaport and the airport . There are also two tourist resorts with a marina and golf courses. Value is placed on corporate social responsibility. The facility requires investments of $ 4.11 billion over 20 years, of which $ 2.75 billion from private sources and $ 1.36 billion from the state. On May 25, 2014, the construction work for the infrastructure of the special zone officially began. In 2015, on the 500th anniversary of the first Portuguese landing, the basic systems should be ready.

trade

The cattle trade with Indonesia has been a major source of income for the residents of the Special Administrative Region in recent years. However, the conditions for East Timorese to cross the border are a problem. Passport and visa must be applied for in the state capital Dili, both with a high financial outlay for the local conditions. The cattle export therefore often runs without paying attention to the official import / export routes, to the detriment of the East Timorese treasury. In general, smuggling via the “mouse paths ” (jalan tikus) is a serious problem. In addition to the cattle trade, distilled palm wine is said to be one of Oe-Cusse Ambeno's main exports to neighboring Indonesia and Dili.

The most important market in the region takes place once a week in Pasar Tono . Other markets take place every six weeks. In addition to fruit and vegetables, local baked goods, tobacco, betel, palm wine, dried fish, eggs and goods from Indonesia such as clothing and household items are traded here. Carrots, cauliflower, large onions, cabbage and potatoes also mostly come from the Indonesian part of West Timor and are accordingly significantly more expensive. The only artisanal products made from Oe-Cusse Ambeno in the markets are woven cloths, betel boxes and clay jugs. The import of goods from Indonesia has increased over the years. The East Timorese treasury was able to collect 15,873.26 US dollars in 2008 through import duties, and in 2010 it was 60,317.86 US dollars.

In addition to a branch of the Central Bank of East Timor, the Banco Nacional Ultramarino (BNU) and the Banco Nacional Comercial de Timor-Leste (BNCTL) are represented in the Special Administrative Region . Among other things, the central bank takes care of exchanging foreign currencies, while the two commercial banks offer, for example, loans from US $ 80 to set up a business. At the BNCTL, 1191 customers in Oe-Cusse Ambeno have loans, 3261 have a savings account (as of 2014).

Infrastructure and traffic

The Inur-Sacato power plant in Sacato has been in operation since 2015. It was built by the Finnish company Wärtsilä . By 2016 it was to be supplemented by a gas and steam combined cycle power plant in order to also supply the new ZEESM buildings. The $ 37 million power plant has four generators with an output of 17.3 kW and is intended to supply the entire Special Administrative Region. The plant is currently operated with light oil ; a switch to natural gas is possible. Before that, only five of the 18 sucos were connected to the electricity grid. Electricity was only generated by diesel generators for a few hours during the night, provided the ferry had brought enough fuel to Oe-Cusse Ambeno. Most often, kerosene lamps are used as a light source.

Almost all households use wood for cooking. The water supply is inadequate, even if over 60% of households have access to clean sources of drinking water. Only 20% have the water on or in the house. The residents of the other households mostly have to get their drinking water from public pipes, wells, springs (89 in the entire Special Administrative Region) or bodies of water. In rural regions, the per capita water consumption is 30 to 60 liters per day, in the city it is 60 to 120 liters. Of this, however, only five liters are drinking water, which always has to be boiled before use. The Indonesians, who in 1999 destroyed or dismantled and removed almost the entire electricity and water network, as well as metal roofs, solar cells and vehicles, are partly to blame for the inadequate infrastructure. 35% of urban and 18.9% of rural households have working toilets.

94% of the Oe-Cusse Ambenos households live in their own home, with 3% the house belongs to the family. Only a fifth of all residential buildings are made of brick or concrete, the majority of the buildings are still made of natural materials such as bamboo, palm fronds or clay. The roofs also mostly consist of palm fronds, with a third of the houses now having roofs made of zinc and iron sheet. The problematic asbestos, which was used during the Indonesian occupation, is only used by 45 houses. Only a fifth of the residential buildings have concrete or tile floors. Otherwise, tamped clay is the predominant building material.

| Share of households with ... | ||||||||

| ... house walls made of ... | ||||||||

| Brick / concrete | Wood | bamboo | Iron / zinc sheet | Palm fronds | Clay | Others | ||

| 20% | 12% | 17% | 2% | 45% | 2% | 2% | ||

| ... roofs made of ... | ... floors made of ... | |||||||

| Palm fronds / straw | Iron / zinc sheet | Roof tiles | Others | concrete | Tiles | Soil / loam | Bamboo / wood | Others |

| 65% | 34% | 0.2% | 0.8% | 16% | 3% | 77% | 1 % | 2% |

| Drinking water supply through ... | ||||||||

| Pipe or pump in the house | Line or pump outside | Public pipeline, well, borehole | protected source | unprotected source | Surface water | Others | ||

| 2% | 18% | 15% | 28% | 34% | 3% | 1 % | ||

| Energy source for cooking | Light source | |||||||

| electricity | petroleum | Wood | Others | electricity | petroleum | Wood | Candles | Others |

| 1 % | 3% | 95% | 1 % | 19% | 77% | 3% | 0.4% | 0.6% |

From Sacato, the A19 highway leads west along the coast to Pante Macassar. The A18 continues to the Indonesian border. The A17 leads from Pante Macassar to Passabe and then north again to Nitibe. Smaller towns are connected to the outside world by poorly developed roads and slopes. Oe-Cusse Ambeno has a total of 350 kilometers of roads, 23 kilometers of which are local roads (2014). The roads are covered with gravel at best, but mostly they are the simplest slopes. The public transport of people between the places is mostly carried out by minibuses with nine seats (Mikroléts) or trucks. Since 2004 there have also been motorcycle taxis in Pante Macassar.