Architecture of East Timor

The architecture of East Timor reflects the traditions of the country's various ethnic groups and the times of foreign rule. Even today, huts made of wood, palm fronds, bamboo , straw, clay and other local materials are built in the traditional style, although more and more modern materials are used, such as roofs made of zinc sheet. Stone are Tranqueiras ( German cover, entrenchment ), old fortifications, built by the Timorese to protect their settlements. The differences in the available materials also have an impact on the local structures, as does the different climate in the individual regions of East Timor. Nevertheless, similarities can be seen.

Traditional architecture

Traditional architecture is defined as all ancestral constructions whose constructive techniques have been passed on from generation to generation.

Huts

In the traditional huts, a distinction is made between sleeping houses ( tetum Uma tidor ) and holy houses ( tetum Uma Lulik ). The Uma Lulik had almost all disappeared during the Indonesian occupation (1975–1999) and especially the wave of violence in 1999. They have been rebuilt since independence, as have the traditional holy houses of the other ethnic groups.

According to official statistics from 2015, 13% of households only have one room, 30% two rooms and 27% three rooms. The houses serve as a dining area and sleeping area, with the sleeping area sometimes being in a separate room with the fireplace.

In traditional building methods, stones are almost only used in the foundation to avoid damage by water, although suitable stones are available. Vegetable building materials predominate. Even clay is usually only used in better buildings. Fixed pillars are missing. Wood is increasingly being dispensed with in newer buildings in favor of concrete, steel and glass, provided that the financial means are available. The wood is taken from the local forests. There you will also find high-quality types of wood, such as sandalwood , red cedar , mahogany , rosewood and teak . Bamboo is abundant in East Timor. It is used in Bobonaro, Cova Lima and Viqueque for structural elements, walls, floors and roofs. Construction takes place in the dry season, when the field work has stopped and there is no rain to hinder the construction work.

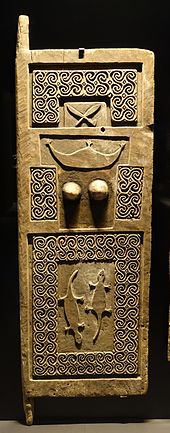

The decorations on the outside of the house are often borrowed from Timorese mythology and provide information about the residents and their social status. The motifs also include water buffalo , roosters, trees (as the origin of life and center of the world) and the crocodile from the Timorian creation myth .

Stilt houses are common among several ethnic groups. There are two different basic types of these. Both basic types have in common the piles, a raised floor and a sloping roof. The first type includes the buildings of the Fataluku and Makasae , the two ethnic groups in the far east of the country. The huts have three levels: foot, room and roof. The roof is divided into two levels with different slopes. The second basic type can be found in Mambai , Bekais , Tetum Terik , Bunak , Kemak and Makalero . The derived types Manatuto and Lefo are also included. This type has at least three different types of piles that support the ground and the roof. Several rings of peripheral bars form the circular roof. In comparison to the neighboring ethnic groups, the traditional round huts of the Mambai, which are still widely used as residential houses, are striking. Otherwise, the traditional huts have a square or rectangular floor plan and a floor area of around 15 m². The entrance consists of two door posts and steps that lead into the living room. Furniture or decorations are rather sparse in the residential buildings.

In 1987, Ruy Cinatti architecturally divided East Timor into seven regions: Bobonaro , Suai ( Cova Lima ), Viqueque , Maubisse , Baucau , Lautém and Oe-Cusse Ambeno . He also took into account the characteristics of the settlements. As a rule, the houses are traditionally very scattered, only sometimes they are grouped around a dense core that is surrounded by stone walls. Elsewhere, the houses stand in clearings and are connected by forest paths. The local type of agriculture also has an influence.

In mountainous Bobonaro, the houses are scattered or in small groups of six to 20 buildings. The rectangular floor plan is about eleven meters long and seven meters wide. The buildings stand on numerous pillars, two sacred pillars stand in the building: the “Pillar of the Earth” and the “Pillar of the Sea Floor”. They delimit the three interior rooms: the entrance area, the central main room (which is twice as large as the other rooms) and the family room, the size of which depends on the needs of the family.

In the region around Maubisse, the settlements consist of three to four houses and outbuildings, which are irregularly distributed from hill domes and mountain peaks down into the valleys. The huts have a circular or elliptical floor plan and a steep roof tapering to a point. The floor of the only room in which people sleep, cook and eat is lowered to protect the residents from cold winds and from outside. Utensils Food and clothing are kept on tables.

The house type of the Baucau region looks like thatched roofs without walls, which stand on eight edge stilts (which creates the octagonal floor plan) and four inner stilts. In the interior, the attic, which rests on four pillars, is also separated. Everyday objects, goods and sacred items are kept in the attic. The 50-centimeter-thick outer covering of Palapa forms the entire outside and protects against rain and heat. The construction time for such huts is three to four months. For the inauguration of the building, the souls of the deceased ancestors are transferred in a ceremony from the old to the new house.

The old settlements in Lautém are larger and more compact compared to other regions and consist of 40 to 50 houses. They are called in Fataluku Lee-teinu ( German "Houses on legs" ). The distinctive huts with the steep pyramidal roofs and square floor plan, which have become the national symbol for all of East Timor, stand on four pillars. They can be up to twelve meters high. The roof is richly decorated with shells, carvings and other symbols of power. The outer walls made of wooden boards are painted. The floor, which is three meters high, rests on a complex frame system.

In the regions of Viqueque where Tetum Terik is spoken, two to ten houses form scattered settlements, each inhabited by only one family. As a rule, they are grouped around clearings in the woods. At 15 meters long and seven meters wide, the houses are larger than in other parts of East Timor. The entrance is on the narrower side. The hut floor is supported by its own structure, while the roof is supported on the outside by its own stilts. The interior is divided into a women's bedroom, the men's bedroom and a kitchen. The storage rooms are located above.

In Cova Lima, where the Suai house type can be found, the houses are in the neighborhood, but the gaps are relatively large and hedges delimit the properties. The rectangular houses stand on stilts with three levels, 80 cm, 100 cm and 150 cm high. The central room, the only one with walls, is the heart of the house, where the owners and the elderly live and cook. Woven straw mats attached to the roof protect the rooms around them from the sun. There are shelves between the rooms, on which food and cooking utensils are stored.

There are two different types of houses in Oe-Cusse Ambeno. In the mountains inland, the settlements are scattered and the houses are single-story and conical. Cinatti called them "the most primitive in all of Timor ". There are larger settlements on the coast. Suspended, woven straw mats served as walls here. Cinatti believed to recognize commonalities with the style Suais and Viqueques and an influence of the Tetum . Local lore reports, however, that the coastal inhabitants are immigrants from southwest Timor, from where they brought their architectural style with them. The seven meter wide and 10 meter long houses stand on two pillars and have a cover of over 50 cm. Mats divide the interior space into a main room and two smaller partitions. The double outer walls are made of two different plant materials.

Tranqueiras

The Tranqueira are the only large historical complexes that were created by the people of Timor.

The majority of them were built between 1150 and 1650 AD, most of them were built between 1450 and 1650. Similar structures from the period between 1300 and 1700 AD are also known from other parts of the Malay Archipelago and Oceania . During this time the El Niño was very effective , which often resulted in droughts in Timor. It is believed that this resulted in famine and conflict between the island's tribes. The walls of the Tranqueiras were built from stacked limestone on top of hills. Within the fortifications there are still platforms and small stone walls. The outer walls usually have an opening or passage. Sometimes walls towards the entrance form a winding corridor.

Colonial architecture

Only a few buildings from the period before 1900 have survived; much of the battle for Timor (1942–1945) between the Japanese and the Allies and the crisis in East Timor in 1999 fell victim. Some buildings were renovated quite idiosyncratically after the independence of East Timor, such as the city market of Baucau . Other colonial buildings are falling into disrepair. From the end time of the colonial era come as a representative of modern architecture , the Banco Nacional Ultra Marino and the Associação Comercial, Agrícola e Industrial de Timor (ACAIT). In these buildings, it is easy to see that the climatic conditions are taken into account through sun protection and ventilation.

Architecture of the Indonesian Occupation

The highlight of the Indonesian occupation is the cathedral of Dili , which the Indonesian dictator Suharto gave to the East Timorese in the 1980s. In contrast to many other buildings, it was spared the wave of violence after the independence referendum in East Timor in 1999 .

During that time, the use of modern materials, such as concrete and zinc sheet, continued to increase, especially in Dili. More than 1000 houses in East Timor are still contaminated with asbestos from this period. To better control the population, many East Timorese were forcibly relocated to new settlements, which led to a de-characterization of traditional architecture. The climatically unfavorable buildings led to a greater demand for electricity due to the air conditioning systems that were now required. A sensible introduction were roofs with two different angles of inclination, which proved themselves with the heavy rainfall in the rainy season.

Modern architecture in East Timor

The steep roofs of the Fataluku houses also serve as a model for modern buildings. The terminal of the Presidente Nicolau Lobato airport and the Catholic Church of Lospalos were built under the Portuguese, while the Indonesians contributed the Tasitolu chapel . After independence, for example, the presidential palace was added, which was built with Chinese help. Several large churches were built in the years after independence. For example in Ossu (2012), Viqueque (2015) and Suai (2012).

Around half of the population still lives in huts, which are often a mixture of traditional and modern building materials. Zinc sheets, for example, are covered with palm fronds, the rest of the structure is often made of concrete, wood or bamboo. Bricks and cement stones are being used more and more in cities. Sloping roofs are preferred among the wealthier population. In any case, the houses are either built according to the western model or owed to the available financial resources. The rural exodus led to urban settlements lacking access to electricity, water and sewerage. There is no overriding planning or regulation.

| Share of households in 2015 (change compared to 2010) with ... | ||||||||

| ... house walls made of ... | ||||||||

| Brick / concrete | Wood | bamboo | Clay | Iron / zinc sheet | Palm fronds | Natural stones | Others | |

| 33% (+ 8%) |

4% (± 0%) |

25% (−6%) |

1% (−2%) |

5% (+ 4%) |

25% (−3%) |

1% (± 0%) |

1% (± 0%) |

|

| ... roofs made of ... | ... floors made of ... | |||||||

| Palm fronds / straw / bamboo | Iron / zinc sheet | Roof tiles | Others | concrete | Tiles | Soil / loam | Bamboo / wood | Others |

| 22% (−9%) |

75% (+ 9%) |

1% (± 0%) |

2% (+1%) |

39% (+ 13%) |

9% (+ 2%) |

46% (−13%) |

4% (± 0%) |

2% (−2%) |

literature

- Ruy Cinatti, Leopoldo de Almeida and António de Sousa Mendes: Arquitetura Timorense , 2016, ISBN 9789898052940 .

Web links

- Património de Influência Portuguesa (English, Portuguese)

- Resoluçâo do Governo 25/2011: Relativa à Protecção do Património Cultural (Government Ordinance on the Protection of Cultural Property; Portuguese, tetum)

supporting documents

Web links

- Eloisa Maria Gago Agostinho de Pina: Arquitetura Sustentável em Timor-Leste , June 2016.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Pina 2016, p. 15.

- ↑ a b c Pina 2016, p. 18.

- ↑ a b A preliminary study on the construction systems of house types in Timor-Leste (East Timor) in: Vernacular Heritage and Earthen Architecture, accessed December 27, 2013.

- ↑ a b c Direcção-Geral de Estatística : Results of the 2015 census , accessed on November 23, 2016.

- ↑ a b c Pina 2016, p. 16.

- ↑ Pina 2016, p. 17.

- ^ Tony Wheeler, East Timor , Lonely Planet, 2004, p. 93.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Sapo: Arquitetura Timorense: Miniaturas do Mundo , accessed on June 6, 2018.

- ↑ Pina 2016, p. 19.

- ^ Laura Suzanne Meitzner Yoder: Custom, Codification, Collaboration: Integrating the Legacies of Land and Forest Authorities in Oecusse Enclave, East Timor. Dissertation, Yale University, 2005 ( PDF file; 1.46 MB ( memento of March 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ a b c d Frédéric B. Durand: History of Timor-Leste , pp. 18 & 30, ISBN 978-616-215-124-8 .

- ↑ a b Lape p. 287.

- ↑ Pina 2016, p. 20.

- ↑ UCAnews, November 9, 1988, Soeharto inaugurates new cathedral and other development projects ( Memento from April 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Pina 2016, p. 21.

- ↑ Pina 2016, p. 22.

- ↑ Direcção Nacional de Estatística: Suco Report Volume 4 (English) ( Memento of the original from April 9, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 9.8 MB)