Rebellions in Portuguese Timor (1860-1912)

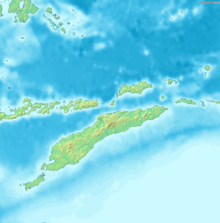

The rebellions in Portuguese Timor (now East Timor ) between 1860 and 1912 were a series of uprisings against the expanding power of Portuguese colonial rule . Up to this period, the European influence was limited to a few small areas of the colony, in the rest of the territory there was only nominal dominance of Portugal over the Liurais , the traditional rulers of the Timorese empires (Reinos) . Two dates mark the delimitation of this period in the history of Portuguese Timor . In the Lisbon Treaty of 1859 , Portugal and the Netherlands first agreed to draw a border between the Dutch western and Portuguese eastern parts of the island of Timor , and in 1912 the Manufahi rebellion, the largest Timorese uprising against Portugal in history, ended. By suppressing the revolts, the colonial power also gained complete control over the interior of the island and the south coast. The Liurais were largely disempowered and the colonial administration expanded.

The uprisings are sometimes also referred to as anti-tax rebellions , since in addition to forced labor, the introduction of poll tax and other compulsory levies led to unrest. The introduction of the poll tax of 1906/1908 is even seen as the main reason for the Manufahi rebellion. However, there were numerous other triggers for the revolts, such as the proclamation of the republic in Portugal, which led to unrest among the Liurais because they also saw their legitimacy at risk, and the extensive development of colonial administrative structures. The rebellions cannot therefore be reduced to just one reason.

backgrounds

Until the middle of the 19th century the empires into which the island of Timor was divided remained de facto independent. The colonial power of the Portuguese was low, especially in the interior, and was mostly limited to low tribute payments (Fintas) . The colonial rulers' income came from the trade in sandalwood and some other export goods. One of the reasons for the weak rule was the constant competition with the Netherlands for supremacy on the Lesser Sunda Islands , which demanded capacities. But in 1859 the first agreement on the drawing of borders was concluded in the Treaty of Lisbon.

Now Portugal could concentrate on expanding and consolidating colonial power. Technical progress and better equipped troops also opened up new opportunities to bring the country under the direct control of Portugal. On the other hand, rebellious Timorese now had the legal and illegal option of obtaining firearms. Thousands of firearms were imported annually. In the 1880s Portugal imposed a trade ban, but it was only with the conclusion of an agreement with the Netherlands in 1893 that the arms trade could be curbed. In addition, the Timorese had a long martial tradition that has its roots in pre-colonial times. In order to create new ways of exploiting the colony (the deposits of the previous main export good, sandalwood were exhausted), the Timorese were also forced to work in road construction and plantations from the 1890s . Even before that, the Liurais were urged to cultivate the coffee introduced in 1815 . The twentieth part of the harvest had to be given up, the rest had to be sold to the colonial rulers at fixed prices. Those rich who could not grow coffee had to deliver a tenth of the rice harvest to the Portuguese. On September 13, 1906 (other sources indicate 1908) the poll tax was introduced for all fathers between the ages of 18 and 60. Each of them had to pay 500 rice in cash unless they were doing contract work, working on plantations larger than 500 acres, or living in an empire that produced more than 500,000 pounds of coffee, cocoa or cotton - another step towards Increase in the production of export goods in the colony. Even wealthy people with fewer than 600 families were exempt from poll tax. As state officials, the Liurais received half of the revenue from the poll tax in their empire, but were not allowed to collect any further taxes themselves, which meant that existing traditional tax systems were abolished and the Liurais were made dependent on Portugal. A problem with the poll tax was the lack of knowledge of the population of the colony. In 1910 a commission came to the conclusion that there were 98,920 families in Portuguese Timor whose heads were liable to pay. The number of different loyal empires was 73 or 75 according to the survey ( Afonso de Castro , governor of Portuguese Timor from 1859 to 1863, had only 47 empires listed in 1867). In particular, the rich on the colonial border and in the crisis area of Manufahi suffered from a population decline.

Portugal struggled to gain and maintain control of the island. In a report from 1872, Governor João Clímaco de Carvalho (1870–1871) divided the Timorese empires into four groups: first, areas under direct Portuguese control, such as Dili , Batugade , Manatuto , Vemasse , Laga and Maubara ; then the empires in close proximity to Dili, especially west of the capital, who had practically recognized Portuguese sovereignty. The empires in the interior of the island, such as Cailaco , did not recognize this, and there was hardly any contact with the rulers. And finally there were the empires on the border with Dutch West Timor, such as Cowa and Sanirin , who openly rebelled against Portugal or with whom, such as Suai, had not had any connections for years. Governor José Celestino da Silva (1894–1908) blamed the landscape for the difficult warfare in the colony. Behind a narrow strip of coast, the island rises quickly to a mountainous landscape almost 3000 m high, where the transport of ammunition was difficult and the Portuguese could be attacked again and again from ambush and from an elevated position. The Portuguese also suffered from the hot and humid climate. The Timorese empires found it easy to forge military alliances that were difficult to combat. Celestino da Silva accused the Chinese of Atapupu (now West Timor ) and other smugglers of fueling the rebellions for profit reasons. In addition, the remoteness of Timor made it difficult for Portugal to supply the colony with troops and weapons. Before 1910 there was not even a regular ship connection with the other Portuguese possessions, let alone with the mother country.

The 1861 rebellion

The phase between 1852 and 1859 was the calmest that Portugal had experienced in its colony. Only two minor uprisings are reported from this period: one was led by the Manumera Empire , and the other was led by the Liurai of Vemasse, Dom Domingos de Freitas Soares, who was exiled in Lisbon that same year, and rebelled in the other .

In the spring of 1861, drawing the population to do forced labor on public projects triggered independent revolts in the Mambai empire of Laclo and in the Tetum empire of Ulmera , both near Dili. The rebels occupied a mountain pass near the colonial capital and blocked food deliveries, threatening a famine. It was therefore necessary to ask the Dutch for supplies. Governor Castro, who was on holiday in Java at the time , brought much-needed weapons and ammunition with him on his return on April 6th and reacted harshly to the rebellions. Castro sent Cabeira , a veteran and expert on the country, against Laclo . Cabeira set up a base in Manatuto , but could only fall back on a few troops from Vemasse. There was fighting in April.

Castro persuaded the loyal Liurai of Liquiçá to undertake a punitive expedition against the neighboring Ulmera. The nearby Maubara, on the other hand, showed sympathy for the rebels. There is speculation that Dom Carlos, the Liurai of Maubara, even incited Ulmera to revolt himself. A few years earlier, in the Treaty of Lisbon, the Dutch had given up sovereignty over Maubara to Portugal in exchange for some Portuguese possessions in the Lesser Sunda Islands. Despite some persuasion from the Netherlands, Dom Carlos never accepted his new masters.

On June 10, Castro declared a state of emergency and distributed weapons to civilians and even to the Chinese population of Dilis . The constant lack of weapons was compensated for with weapons from the trading company and deliveries from the Dutch from Batavia . In addition, Castro was able to fall back on 40 Indian warriors who had come into exile in Timor after the Sepoy uprising against the British in 1857. But the requested reinforcements from Goa still needed time to get to Timor. Castro therefore asked the neighboring Dutch colonies in the Moluccas for support. The governor of Batavia then dispatched the Citadelle d'Anvers , a steam-powered frigate that reached Dili on June 22nd. Three days later, the ship continued along the Manatuto coast, pushing the rebels from their forward positions.

On August 26, the rebellion in Laclo was put down. The rebel camp was burned down and local allies were allowed looting and headhunting of the rebels. The state of siege on Dili has been lifted. The victory of Portugal was extensively celebrated by Governor Castro in Dili, including the Likurai dance , which is traditionally performed by women for the Timorese warriors returning from war. To do this, the heads of the slain enemies were carried through the town in a procession. Headhunting was part of funu , the ritual war. Usually the heads of the slain enemies were carried to the home village accompanied by dark chants (the lorsai ) and the Likurai dance , where they served as sacred objects ( lulik ) .

With the beginning of the rainy season , Castro threatened to lose the support of his Timorese warriors, as they now had to look after their fields. In order to gain the loyalty of the Liurais, Castro announced that he would lead the troops into the still rebellious Ulmera himself. On September 18, 1200 local warriors gathered in Dili. In the revolting empire Castro also met support from Liquiçá, so that he now had 3000 men. Ulmera was overrun and the ruler of Ulmera and his son were taken prisoner to Dili. Another victory ceremony was held there, where the captured Liurai kneeled down and pledged to pay a large amount of compensation. The heads of the fallen opponents were also presented again. Castro later wrote of the rebellion: "One must use coercion, not to tyrannize, but to obey the law and to force a lazy people to work."

In March 1862 a corvette from Macau finally came to Timor. Although these reinforcements came too late to intervene in the rebellion, the money and troops on board were now used to, as Castro said, “to consolidate our dominance, to strengthen our officials in their delicate position and to use resources to make better use of our colony for business and industry. ”Castro had plans to establish a coffee plantation in every kingdom of the colony. He also established military posts in each district to weaken the sovereignty of the Liurais. Historian Durand points out that despite the brutal crackdown on rebellions, the introduction of forced labor and the ruthless division of the colony into ten military commanderships, Castro is said to have been an advocate of Timorese traditions. Also, given the colony's conscious fragility, he preferred limited interventions.

In June 1863, a Makasae rebellion was suppressed by Laga and the village burned to the ground. The former rebel chief was captured by Laclo. But Governor José Manuel Pereira de Almeida could not look forward to this victory for long. After only one year in office, he was driven out by a revolt of his troops. The reasons were unpaid wages and Almeida's dictatorial style of leadership, as a result of which European and Timorese members of the Batalhão Defensor mutinied against the inner circle of officials from Goa. The Capitão China and one Indian were killed, the other Indians had to flee to Batugade. Until Almeida's successor, José Eduardo da Costa Meneses, arrived two months later, the colony was ruled by a council of dignitaries. Costa Meneses solved the financial problems that had led to the revolt by borrowing from the Governor General of the Dutch East Indies . When Costa Meneses returned to Lisbon in 1865 due to illness , he was brought to justice for having exceeded his competences by borrowing. Costa Meneses died during the trial. Now, as governor , Francisco Teixeira da Silva had to eliminate the unpleasant consequences of the mutiny. Promotions and pay increases by his predecessor have been withdrawn.

In Cotubaba (today Tutubaba ), on the north coast near Batugade, there was an attack on Portuguese troops by Timorese warriors in 1865. At the same time, the Liurais of Cowa and Balibo united to revolt against the colonial rulers. Portugal responded by bombarding the coast with the 13 guns of the steamship corvette Sa de Bandeira . The next uprising occurred in Fatumasi in 1866 . This time the ruler of Ermera supported the Portuguese in the crackdown .

The rebellion in Vemasse, Lermean and Sanirin

In the spring of 1867 the Kemak from Lermean ( Raemean ?), Who were under the sovereignty of Maubara, rose . Governor Teixeira da Silva put down the resistance in an unequal battle. In the decisive battle, which lasted 48 hours, the rebels had to defend themselves against a superior force that was superior to firepower. 15 villages were captured and burned down. The number of victims among the Timorese is not known, the Portuguese put their own casualties at two dead and eight wounded. The territory of Lermeans was divided among the neighboring kingdoms.

In August 1867 the inhabitants of the kingdom of Vemasse, to which Laga belonged, rebelled. The warriors besieged Lalcia . Teixeira da Silva ended the siege and put down the uprising with the help of the allied kings of Motael , Hera , Laculo ( Lacoliu ?) And Manatuto. The Liurai of Vemasse was replaced by his deputy, the Dato-hei , who swore an oath of alliance. Although he promised peaceful relations with his neighbors, 15 years later there was fighting between Vemasse and Laleia , for which the commander of the military headquarters was held responsible. The nearby empires of Faturó (Futoro) and Sarau (Saran) were also moved to an alliance with Portugal.

In 1868 the Portuguese sent a force to Sanirin (Sanir, Saniry) in the Batugade military command, whose Liurai refused to pay taxes. The Kemak of Sanirin were officially tributaries to Balibo.

The Cowa Rebellion

In the Tetum empire of Cowa the resistance had been seething for several years, but in 1868 this area was also to be pacified with a large-scale military offensive. The Cowas dominion extended to the north coast and the area of the Dutch West Timor . The fact that Cowa was also supported by rulers from the western part of the island worried the Portuguese even more. The Batugade Fort , already in the Cowa area, became the base of the Portuguese military expedition, which consisted of troops from Dili and irregular units from Manatuto, Viqueque and Luca . On August 20, 1868, the Portuguese destroyed three fortified settlements owned by the resistance. The headquarters were bombed with artillery and missiles, which resulted in a high number of casualties. The Portuguese side had only one dead and one injured.

But since it was not possible to take more well-fortified forts of the rebels in the course of a month, the Portuguese had to withdraw as far as Batugade. On the Portuguese side, 83 were killed, including the leader of the local troops from Laclo. Teixeira da Silva then dispatched a reinforcement of 1200 men from regular troops, loyal Moradores , warriors of the Liurais of Barique , Laleia, Ermera, Cailaco and Alas and two howitzers . Cowa was to be bracketed with 800 men from northern Batugade and a similarly large force from the other direction. Another month later, more troops from Oecussi , Ambeno , Cailaco and Ermera were brought to Batugade.

There was never really any doubt about the Portuguese's success, but the new governor João Clímaco de Carvalho wanted a symbolic victory. In May 1871 he and his entourage arrived at Batugade to meet the queens of Cowa and Balibo. Balibo was on Cowa's side at the time. The ceremony of submission should, according to Carvalho, be "solemn and follow all formal customs". The Queen of Balibo, Dona Maria Michaelia Doutel da Costa, and her entourage reached Batugade punctually on May 29, but the Queen of Cowa, Dona Maria Pires, did not appear. On June 1, 1871, Dona Maria Michaelia signed the agreements submitted to her, which meant the submission of Balibo as a vassal of Portugal. By doing so, Balibo agreed to pay taxes to Portugal and provide arms aid. Cowa did not recognize the supremacy of Portugal until 1881.

The revolt of the Moradores

Governor Alfredo de Lacerda Maia , who took office in 1885, is described as "young, enthusiastic, hardworking and apparently honest"; a governor who wanted to advance the fallow colony. In collaboration with some Liurais, he tried to revive coffee growing. He traveled several times to the interior of the island, to the scattered Portuguese posts on the north coast and to the south coast of the island, which had been almost abandoned by the Portuguese in previous years.

Between May and June 1886 Maia had to grapple with a revolt of Maubara. At the beginning of his tenure, he had only 50 European soldiers, 150 Mozambicans and eight cannons, but in the expedition against Maubara were first breech-loading guns used whose construction has enabled a more rapid firing. There was no real pacification, but there was also no defeat for the Portuguese, as it had happened several times in the past against Maubara.

The historian Pélissier praises Maia for his accomplishments in the administration of the Portuguese possessions on the north coast of the colony, but names the appointment of the sub-lieutenant (alferes) Francisco Ferreira as his secretary as a crucial mistake. Ferreira had already attracted attention in 1879 through atrocities during the fight against rebels. As a colonial officer, he looked down contemptuously at the Moradores, without which Portugal would not have been able to survive militarily in its colony. They were Timorese who were recruited by Liurais loyal to Portugal without receiving any pay from the Portuguese. Groups of them were stationed in Dili, Batugade and Manatuto. The Mozambican soldiers were forcibly deported who were constantly drunk and neither understood Portuguese nor how to handle Remington rifles. The Europeans were of no use anyway due to constant illness from the unhealthy climate. Since the governor refused to hear the Moradores' multiple complaints about Ferreira, a hundred of them decided to ambush Ferreira. They saw their honor injured, which was worse for them than death.

Unfortunately for Maia, on March 3, 1887, during their ambush on the road between Dili and Lahane , the Moradores did not find the secretary, but the governor. When he tried to flee badly injured, they decided to give him the coup de grace. He was spared the Timorese ritual of beheading. Two officers of the Moradores feared that the mystical connection with the Portuguese crown would be severed, which would shake the island.

Portuguese officials were so shocked by the murder that they declared a state of siege on Dili and posted cannons and machine guns on the streets. According to later press reports in Macau, Dili fell into “total terror,” while the murderers actually fled to the mountains. Ferreira was placed under the protection of the head of the mission and left the next day on board a steamer Dili for Surabaya . From there, the superior colonial authorities in Macau were notified of the incidents by telegram. They dispatched a force of a hundred European soldiers, eight non-commissioned officers and one colonel, which arrived in Dili on March 29th, with an unusual speed. At that time there were only about 100 to 150 European soldiers in the colony; in addition there were roughly the same number of Moradores and Indian soldiers. The gunboats Rio Tâmega (1887), Tejo (1888) and Rio Lima (1890) were later dispatched to Timor to provide further support .

The murder sparked heated controversy over the question of guilt between the navy, the army, the Catholic Mission, the opponents of the monarchy, the Freemasons, the people of Macau, the Portuguese in Europe, the press and many others. The new governor António Francisco da Costa (1887-1888), who arrived in Dili in August, began a large-scale investigation. The secretary Ferreira was quickly identified as the cause of the unrest. It was more difficult to determine whether he was the sole culprit or just the scapegoat. The ringleaders of the revolt had fled into the hills so that the military had to conduct searches in Liquiçá. There were riots in various empires too, most notably in Manatuto. Eventually the suspects were captured, taken to Macau on the Rio Lima gunboat and incarcerated in the infamous Fort Monte. It is still not clear whether they were really guilty. Some Timorese, like Lucas Martins, the ruler of Motael, were brought to justice in Goa, which Martins owed mainly to the less than brilliant defense of a Timorese missionary. The Moradores battalion was initially disbanded. Although most of the Liurais neither allied themselves with the insurgent Moradores nor used the chaos in the colonial capital to conquer them, Portuguese rule in Timor had been seriously shaken by the revolt. It was not until November 1889 that they had recovered to such an extent that a major military expedition could again be sent. The assassination of Maias was the beginning of uprisings by numerous Liurais, among them Dom Duarte and his son Boaventura von Manufahi.

The Maubara Revolt

Governor António Francisco da Costa tried to expand the military and administrative control of Portugal over his colony, including through a more effective tax collection system. With this, the colonial administration continued to attract the anger of the Liurais, which finally erupted in the revolt of Maubara under Governor Cipriano Forjaz in 1893. The ruler of Maubara attacked the military posts Dato and Vatuboro (Fatuboro) , killing several soldiers. At the same time, he offered the Dutch to place themselves under their suzerainty again, as it had been before 1859. Governor Forjaz then called in the gunboat Diu for assistance.

The Diu only needed eight days to travel from Macau to Dili and arrived on June 21. Just a few decades ago, such a quick response would not have been possible. Shortly afterwards, the Diu shot at Vatuboro with its Krupp cannons and Hotchkiss rapid fire guns. Then Dato was shot at and a landing squad was released. It consisted of 37 African soldiers, 220 warriors from Liquiçá, 60 from Maubara, 96 Moradores and 204 other soldiers. The ruler of Atabae , who also rebelled, was given an ultimatum. On July 14th, he agreed and swore allegiance to the King of Portugal. Atabae had to pay compensation to Portugal and Cotubaba in the form of money, buffalo and pigs. In November Maubara confirmed his vassal status to Portugal in a written contract.

The consequences of the Maubara massacre extended far beyond the sheer number of those killed in the fighting. Because by the rotting corpses and animal carcasses burst into Maubara, but also in Tibar , Atapupu and Alor , the cholera made. A connection between fighting and the outbreak of the epidemic is also known from the colonial wars of the Netherlands on Sumatra against the Padri and Aceh and that of the British in Egypt .

The Manufahi War

The Portuguese governor José Celestino da Silva continued to consolidate Portuguese rule after taking office. Other written contracts about their vassal status were concluded with various empires, such as Hera and Dailor in January 1894, Fatumean in September 1895, and Buibau (Boebau) and Luca in April 1896. The value of these contracts was questionable, especially when they were under pressure came about. New military posts were established throughout the colony.

In addition, Celestino da Silva launched three offensives against different empires, the first of over 20 campaigns during his tenure. For this he had 12,350 Timorese soldiers who were commanded by only 28 Europeans. In October 1894 he fought against Lamaquitos , Agassa , Volguno and Luro-Bote and in March 1895 against Fatumean, Fohorem , Lalawa , Casabauc , Calalo , Obulo and Marobo (Marabo) . The notorious Portuguese lieutenant Francisco Duarte led the operation against Obulo and Marobo, who had threatened to transfer to the Dutch. Duarte's attack failed, so he got reinforcements from Dili in April. 6000 additional moradores and artillery were brought in under the command of Captain Eduardo da Câmara, who had already gained experience in India and Mozambique. The two Timorese empires received support from Cailaco, Atabae, Baboi , Balibo and Fatumean. the Portuguese could not beat Obulo until the end of May. Spurred on by the success, Câmara continued to advance to Cowa without waiting for reinforcements already close at hand. There his troops were wiped out by the Timorese in September 1895, and all European officers were also killed. Câmara was beheaded. In the following months another 300 African soldiers came to Timor and Governor Silva started an aggressive pacification war. Lieutenant Duarte and Captain Francisco Elvaim commanded the punitive expedition with almost 6,000 men, including 40 Portuguese. Cotubaba was razed to the ground. From Sulilaran all residents had left their possessions and fled. The Liurai from Balibo surrendered immediately. The village of Dato-Lato (another source after Dato-Tolo ), which belongs to Sanirin , was destroyed on the night of August 17, 1896, because it was believed that the ruler of Cotubaba had fled here. In view of the hundreds of deaths there, the rulers of Atsabe and Deribate, allied with the Portuguese, withdrew their troops. The residents of Cowa fled to West Timor. In the ritual center, the Portuguese found the heads of Câmara and others hanging on a tree. Governor Silva now sent Lieutenant Duarte to Deribate to punish it for its desertion. The following massacre killed over 400 people. The empires of Deribate, Cotubaba, Sanirin, and Cowa were declared dissolved in 1897. Sanirin was subordinated to Balibo, Cowa under direct Portuguese administration and the other three empires divided under Ermera, Mau-Ubo (Mahubo), Atsabe, Cailaco and Leimea . Large parts of Cowa remained depopulated for over 30 years.

In August 1895, Silva turned against the Empire of Manufahi when it refused to pay the Fintas and to do slave labor. The Liurai of Manufahi, Dom Duarte, then united with the rulers from Raimea ( Raemean , Raimean ) and Suai and other areas to resist through a blood pact. Boaventura, son of Dom Duarte, was sent to Cailaco, Atsabe, Balibo and other empires to make further alliances. Even before Celestino da Silva had mobilized his troops, Dom Duarte managed to beat a column of several hundred soldiers in Portuguese service and to capture their weapons. Portugal then sent a force with 3,000 fighters. The fighting lasted for 50 days without either side being able to win the war. The rainy season ended the fighting for the time being. Again in 1896 Dom Duarte declared his willingness to pay the Fintas and also allowed the establishment of a Portuguese military post on his territory. However, he refused to swear allegiance to the governor in the colonial capital Dili . The colony still did not calm down. On July 17, 1899, Lieutenant Francisco Duarte fell during the siege of Atabae. The Fort Conselheiro Jacinto Cândido in Batugade was temporarily occupied by rebels from Fatumean, while the troops actually stationed there fought elsewhere. And the financial outlay was also high. In 1896, Celestino da Silva therefore demanded 15,000 to 20,000 patacas from the then responsible colonial government in Macau in order to be able to cover the costs of the ammunition that was used against the rebels. The later governor Teófilo Duarte (1926–1928) criticized that Celestino da Silva's military expeditions had cost “an enormous amount of money” and that such special security measures “do not exist in any other colony”.

Dom Duarte, however, continued not to pay his taxes until September 1900 and did not allow the Portuguese to have a base on his land. Governor Celestino da Silva therefore assembled a force of 100 officers, 1500 Moradores and 12,300 Timorese warriors. They now moved south in three columns against Manufahi and his allies. Maubisse was taken on October 18 and Letefoho on October 26. It took four days to defeat Babulo . Dom Duarte holed up on Mount Leolaco . Attacks and counter-attacks dragged on from November 6th to 19th. Smallpox and dysentery broke out among the Portuguese, and Dom Duarte's men were sick with cholera and dehydrated. In view of the impending defeat, Governor Celestino da Silva declared on November 21 that he would grant mercy and returned to Dili. In return, Dom Duarte abdicated in favor of his son Boaventura as Liurai. For Celestino da Silva, given the tenacity of the Timorese resistance, this compromise was acceptable.

Celestino da Silva was of the opinion that future wars could only be prevented if the military, civil officials and missionaries did a good job. He therefore founded schools in various parts of the colony, in which the population was taught the basics of agriculture in order to apply them to coffee growing. Celestino da Silva set up a regular ship connection to Macau and had a telephone network set up in the colony. In addition, new markets were established. Under Celestino da Silva, the district tax previously levied in kind was converted into a poll tax. Private plantation and trading companies emerged.

Further rebellions broke out: in Ainaro (1902), Letefoho and Aileu (1903), Quelicai (1904) and finally again in Manufahi (1907). In 1908, Portugal decided to strip the Liurais of authority and place jurisdiction in the hands of the colonial administration. The new Portuguese administration built on the native plains below the Liurais, the Suco . The choice (or rather, the confirmation) of the leaders of the sucos was dependent on the approval of the Portuguese. A posto was chosen from a group of sucos and these postos were gathered in a concelho (council). This concelho supervised the postos by the Portuguese administration. The reorganization was intended to break the traditional structures and destroy the influence of the family clans, a method that had already been used successfully in Portugal's African colonies.

But the political and administrative restructuring changed neither the local ideology nor everyday life. The leaders of the sucos still needed the support and knowledge of the liurais and their kin connections. Traditional hierarchies remained, supported by local traditions and worldviews. The result was a system on two levels - one colonial and one native, traditional. In addition, the Timorese seemed to become more and more rebellious, the further the non-cultural work system “money for work” was introduced.

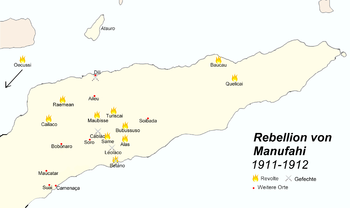

The Manufahi Rebellion

The fall of the monarchy in Portugal

The prologue to the Manufahi rebellion was the overthrow of the monarchy and the proclamation of the republic in Portugal on October 6, 1910. After the first rumors had spread, a telegram arrived on October 7, 1910 with the official message about the new government of Dili. The next day it was confirmed again by the Portuguese cruiser São Gabriel , which was moored in the port of Darwin . Governor Alfredo Cardoso de Soveral Martins officially announced the proclamation of the republic on October 30; the blue and white flag of the royal Portugal was overtaken and the new green and red flag of Portugal was set with a salute of 21 rounds. It took until November 5th to adjust the administration to the new situation. This mainly included the appearance and national emblems , such as letterheads for official letters, symbols on administrative buildings, military uniforms and the like. An exception was the Pataca banknotes, which with the royal symbols remained in circulation until 1912. Soveral Martins left Dili in early November after his wife tragically passed away. The office was continued by Soveral Martin's secretary, Captain Anselmo Augusto Coelho de Carvalho . He was replaced on December 22, also by protocol, by Captain José Carrazeda de Sousa Caldas Vianna e Andrade . But the changes were only noticeable for the urban population and the Timorese educated in Europe. The rural population did not notice any differences and the Liurais were rather confused by the abolition of the monarchy. They drew part of their claim to power from sacred objects (lulik) that were owned by the ruling families. When the Portuguese subjugated the Timorese, they gave the Liurais as vassals the white and blue Portuguese flag, which in the eyes of the Timorese, like the flagpole itself, became sacred objects that legitimized the rule of the Portuguese and the Liurais loyal to them. The change of flag therefore led to a loss of power from the perspective of the Timorese. Additional chaos was caused by the expulsion of the Jesuit missionaries , who, as holy men, also represented a source of the Portuguese claim to power in the eyes of the Timorese. The anti- clerical currents in Portugal had also found fertile soil in Dili among the Europeans and assimilated Timorese. A few republican cells and even a Masonic lodge were formed . On December 23, the Jesuits were expelled from Soibada on instructions from Dili , which ultimately meant a setback for the Portuguese in the region.

The revolution and its goals were difficult to convey to the Liurais. In addition, some officials worked before the arrival of the new governor Filomeno da Câmara de Melo Cabral (1911-1917) against the idea of a republic. Far from home, many Portuguese were far more conservative in administration. And the Dutch also supported anti-republican tendencies among the Timorese by distributing pictures of the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina . In addition, the Netherlands saw the confusing situation as an opportunity to appropriate the disputed territory of Lakmaras with European and Javanese troops. The Liurais feared the loss of many privileges. According to the republican ideals, they could no longer raise local taxes or require labor, and the sons of the Liurais would no longer have the sole right among the Timorese to attend colonial schools.

The beginning

In 1911 Boaventura rose against the Portuguese colonial rulers for the last time. The Manufahi rebellion or the Boaventura rebellion was probably the bloodiest, but in any case the uprising that is deeply anchored in East Timor’s memory, especially since it is better documented than any previous rebellion through colonial reports, official reports, newspaper articles and eyewitnesses . It is also one of the largest surveys in Portuguese colonial history . At that time, the Manufahi empire had about 42,000 inhabitants, just a little less than today's Manufahi community. The main town was already at that time Same . The population lived from growing grain and fruit, horses and sheep were also raised and coffee and tobacco were grown. The region was known for excellent leather, gold and silver work .

The claims from the poll tax of 1910 exceeded the possibilities of Manufahi. When another increase was announced by the Portuguese commander of Suai in 1911, Boaventura and several other liurai in the region called for a meeting and the recall of the colonial official. The poll tax should be increased from one to two patacas and ten avos. In addition, there was a ban on local people from cutting sandalwood, a tax of two patacas per felled tree, the registration of livestock and coconut trees, and a tax of five patacas for slaughtering animals for festivities. On October 5th, the anniversary of the proclamation of the republic, to which Governor Cabral had invited all liurais and datos to a celebration in Dili, several rulers gathered in a suburb of Dili. According to contemporary Portuguese reports, they were planning a conspiracy in which all Europeans would be murdered. The presence of an English merchant ship in the port of Dili is said to have dissuaded them from their plan.

Due to the threatening situation, the Portuguese post in Suai was evacuated on December 8th. A Mozambican soldier who was supposed to bring reports to Bobonaro was killed on the way there. The actual beginning of the rebellion is December 24th. That morning, the Same military post was attacked by some Boaventura men. Lieutenant Luís Álvares da Silva, the commandant of the post, two other Portuguese soldiers and a Portuguese civilian were killed. Silva's wife, who was nursing her son, was dragged out of the post and her husband's head was placed on her lap. They were spared themselves. The rebellion quickly spread to the neighboring regions. The posts in Hatolia , Ermera and Maubisse were given up and the European population fled to Dili. The plantations lay fallow.

On December 29, 1,200 Timorese sought protection in the Dutch enclave of Maucatar for fear of Portuguese reprisals . among them the Liurai of Camenaça (Camenassa, Kamenasa) and his entourage, actually allies of Boaventura.

Portugal's reaction

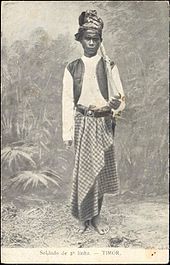

The military commander of Manufahi had already started at the beginning of the rebellion to attack insurgent positions and occupy strategically important points. At that time, 76 European and 96 Asian soldiers were stationed in the colony. In addition, there were armed forces from local Moradores, Arraias and warriors from the allied kingdoms around Dili. The armament decreased sharply with decreasing status. The colonial soldiers had Remington rifles or flintlock rifles that Moradores only Suriks or machetes . But the shortage of firearms and gunpowder put the Timorese rebels at a disadvantage from the outset. Most of them, too, were armed only with spears, bows and arrows and suriks.

On January 5th, Governor Cabral and 200 men moved to Aileu and set up a base there. The 25 European soldiers and Moradores were joined by loyal Arraias along the way. After three weeks in the mud of the rainy season, much of the territory was again under Portuguese control. The weakened units were reinforced to 2070 irregular fighters, 264 Moradores, 65 professional soldiers and eight officers. But the troops were still too weak to attack the capital Boaventura. Therefore, Cabral tried the old Portuguese colonial style to play off loyal and rebellious Liurais against each other. He received support from the so-called traitor Liurai Nai-Cau (Naicau) and his nephew Aleixo Corte-Real from Soro . In 1907 Nai-Cau had gained Soros independence from the empire of Atsabe. It bordered Manufahi to the east and south. When Boaventura attacked Ainaro, Nai-Cau came to the aid of the threatened military post.

On February 19, 1912, the Sydney Morning Herald reported :

“Most of the island of Timor is in turmoil. Ramea tribe men attacked Dili, killing many residents and burning many houses. Major Ingley, Lieutenant Silva and several soldiers were killed during the street fighting. The heads were cut off by the rebels and placed on stakes. The government building was looted. "

The report exaggerated the situation, but Dili was indeed seriously affected and European families were evacuated. Nevertheless, the city was saved from sacking by hastily assembled defenders. To reinforce, Portugal sent the gunboat Pátria from Macau under the command of Lieutenant Gago Coutinho , which arrived on February 6th. On board were 220 European soldiers and Indian Marathas and 204 Africans from Mozambique. On February 11th, the English steamship St. Albans reached Companhia Europeia da India Dili with another 75 soldiers (half Europeans) and on February 15th the English ship Aldehanam with the eighth Companhia Indigena de Moçambique. Jaime do Inso , second lieutenant on board the Pátria , reported that three heads had been hung in Laclo, evidence of the "hideous cruelty of the war of primitive people," as he wrote. It may have escaped the fact that Governor Castro had used this Timorese tradition himself for his victory celebrations 50 years earlier.

According to Inso, Manufahi, as the center of the rebellion, should be isolated and cut off from support from the neighboring allied realms of Raimea, Cailaco, Bibisusso , Alas and Turiscai (Toriscai) . The Portuguese armed forces were divided into four columns. The main column that had taken Maubisse was led by the governor himself. It consisted of 4,000 men, including 20 Europeans, 200 Africans, 500 Moradores and Arraias, and had a Krupp -BM75L gun. The second column moved from Soibada with an Indian company, a few hundred Moradores and a Maxim machine gun . The third column was based in Soro and consisted of two Europeans, 70 Africans and 200 Moradores. A machine gun was also available here. The fourth column with a hundred Moradores was on the border with West Timor. In some cases, troops were even called in from Angola . After several skirmishes, the realms of Fatuberlio , Turiscai and Bibisusso were defeated in March , while the Liurai of Cailaco and Atabae announced that they would rather fight to their death than submit. The fighting continued into May. Now a rebellion broke out in the exclave of Oecussi.

On April 29, the Portuguese Zambézia arrived after just 31 days from Lourenço Marques in East Africa . On board were another 223 African soldiers and 19 Portuguese officers. In addition, another company of soldiers was mobilized in Mozambique to be sent to Timor on board the Portuguese ship Zaire . The Zaire only reached Timor in July.

The end

It seems that Boaventura would have been ready for a peace settlement by then, but Cabral now wanted an ultimate victory. He now had 8,000 irregular fighters, 1,147 soldiers and 34 officers, the largest European armed force on Timor to date. On May 27, 1912, he attacked the fortified positions of Boaventura on Mount Cablac and occupied the mountain in the following days. The main rebel forces withdrew to Riac , on the lower slopes of the Cablac, where they were besieged by the Portuguese between June 11 and 21. Eventually the rebels and civilians were forced to flee to Mount Leolaco . There Boaventura was encircled along with 12,000 men. With several thousand of his fighters, he decided to break the siege lines between August 8 and 10 and escaped. According to a report by Insos, the remaining fighters and civilians were slaughtered by the Portuguese over the next two days and nights. More than 3,000 Timorese are said to have been killed.

The Pátria was again ordered to Timor after she had been recalled to Macau due to the revolution in China . She brought much-needed weapons and other supplies to Cabral's ground forces. On the south coast of the island, the Pátria shelled the last positions of Boaventura, near the residence of the Queen of Betano . According to Lieutenant Inso, a thousand people died as a result. The noise of the guns and their devastating effect had, in addition to the military, also a clear psychological effect on the Timorese. Boaventura was encircled and finally captured on October 26, 1912.

The Pátria was used several times against other rebels in the course of 1912, for example in Oecussi. In Baucau , marines from the Pátria, under the command of Inso, defended the place against insurgents between June 29 and July 25, for which the lieutenant received several commendations. There was another uprising in Quelicai as well. However, these uprisings were localized. The state of emergency for the colony had already been lifted on August 16, 1912 and a victory celebration was held the next day. With the permission of Cabral, the Moradores again held the Likurai dance with the severed heads of the enemy. Governor Celestino da Silva had previously not resorted to the macabre tradition.

The consequences

According to Portuguese information, a total of 12,567 Timorese were taken prisoner and 3,424 rebels were killed. The losses of the colonial troops amounted to 289 dead and 600 injured. It is estimated that 15,000 to 25,000 people died as a result of the Manufahi rebellion, representing more than 5% of the colony's estimated population. In addition, there are victims of the accompanying dysentery epidemic and the dead of the simultaneous uprisings in Baucau (2000), Lautém (300) and other places. The entire fighting in the colonial "pacification" of Manufahi between 1894 and 1912 probably cost 90,000 people their lives and depopulated entire areas. Although the numbers are very uncertain, the official population figure of 303,600 in 1913 was by far the lowest in decades. Boaventura was incarcerated on the island of Atauro , where he presumably died. After 1913 there are no more reports about him. According to oral tradition, he is said to be buried at the gate of the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili.

The loyal Liurais, without whom a victory for the Portuguese would probably not have been possible, were given military ranks of major or lieutenant colonel as thanks. Those who first submitted to the Portuguese were rewarded with territorial gains - at the expense of the rebellious empires. Some areas, such as Raimea, were placed under direct colonial administration in order to set up plantations there. Perished or captured rulers, such as Afonso Hornai de Soares Pereira of Bibisusso, were replaced by loyal supporters of Portugal, regardless of traditional succession. The widows of fallen arraias and those wounded in battle received coconut and cocoa trees or other tax-free allowances. Residents of the rebel areas were forced to grow coconut and cocoa trees and to do unpaid work on plantations. In addition, each family had to maintain 600 coffee bushes. In 1916 alone eight million coffee bushes were planted in this way. Timorese between the ages of 14 and 60 had to do labor service.

rating

Historians disputed whether the last Boaventura uprising was another attempt to drive the foreigners out of the country, a protest against the poll tax that has existed since 1906 and the disempowerment of the Liurais, or a rebellion with tendencies towards a first Timorese national feeling , especially letrados (also Assimilados ) made common cause with the "primitive" warriors. Both Dom Duarte and his son Boaventura had contacts with these Timorese with European education from Dili, some of whom were even members of the Masonic Lodge. Some Moradores from this group also supplied the rebels with gunpowder and cannonballs. It seems certain that the independence movement in the Philippines was a model for these Timorese. This is also known from the neighboring island of Flores , where there were ten armed uprisings against the Dutch colonial rulers in 1911/12 alone. However, there are no written sources to show that Boaventura was striving for an independent nation. It is also an open question how the 5,000 assimilated people should have united the hundred or so feudal dwarf states that made up the colony, especially since most Liurais were skeptical about the possible success of the rebellion and therefore kept quiet. Even if the 1911/12 rebellion was the height of the Timorese resistance against Portugal, it was largely confined to the western part of the colony and the rebels were surrounded by neutral or even pro-Portuguese rulers.

The reason for the rebellion was that the Timorese shouted “Venham ca buscar duas patacas, se são capazes!” (“Come and get your two patacas, if you can!”) As a battle cry at the beginning of the rebellion. At least the tax hike was an impetus and a major reason for the uprising. It seems clear that the change in the form of government in Portugal and the associated loss of tried and trusted symbols of power that were regarded as sacred was another reason for the outbreak of the revolution. In some places the new flag of Portugal had been torn down and replaced with the old flag. In this context, there was also the fact that the Netherlands, Portugal's old competitor, would not have been bothered if the Portuguese half of the island had also fallen into their hands due to royal desires of the Timorese.

Historians see the crackdown on the rebellion as a black mark and a precedent in the history of the first Portuguese republic. This was followed by major massacres in the Portuguese colonies in Guinea , Mozambique and Angola. Portugal no longer tolerated widespread disobedience. Schlicher assigns the Manufahi rebellion to the post-pacification revolts and places them in a row with uprisings in other colonies at the end of their occupation, such as the Maji-Maji uprising in German East Africa or the 1906 uprising in Bali against the Dutch, as resistance to the inevitable.

Queen Maria de Manufahi, Boaventura's widow, had been a member of FRETILIN since 1974 and supported the independence of East Timor. During the violence in East Timor in 1999 , residents hoped for protection from the spirit of Boaventura from the marauding pro-Indonesian militias . The soldier Alfredo Reinado (1968–2008), who rebelled against the government, saw himself in the Boaventura tradition, to whose homeland Manufahi he maintained friendly contacts. During Reinado's escape from Same from Australian soldiers in 2007, the spirit of Boaventura helped him to make himself invisible, the rebel said. In a ceremony, Reinado was declared the reincarnation of the Liurai of Manufahi by local, traditional guides. When assassination attempt on the East Timorese governance in 2008 he finally died.

Boaventura became a central symbol of heroic national history. The battles on the Cablac are transfigured today in East Timor and especially in Manufahi as the heroic battle of Boaventura, the Liurai himself as the national hero of East Timor and the target of worship in mass culture and among youth gangs . Among other things, the Dom Boaventura Medal was named after him, the highest honor in the country.

Portuguese Timorese Society after the Rebellions

On August 13, 1913, the representative governor Gonçalo Pereira Pimenta de Castro restructured the colonial forces. He dismissed the commanders of the Moradores and disbanded their companies. The Moradores were placed under the direct command of European officers.

Due to the First World War, Governor Cabral remained in office until 1917 and shaped the colony with his reforms until the 1940s. He tried to bypass the power of the Liurais by using the sucos as the first colonial administrative level, bypassing the traditional rulers. In addition, one level above the civil administration was divided between the 15 military commanderships and the Liurais were subordinate to the military commanders. Timorese from the lower aristocracy of the Dato, who could speak and read Portuguese and belong to the Christian faith, were appointed as Chefe de Suco . They served as mediators between the population and the colonial government and were given administrative tasks. Social, ritual and political issues within the Timorese continued to be dealt with by the Liurais.

Already at the end of the 19th century the Catholic Church had intensified missionary work and from 1904 onwards the children of Liurais were educated and educated in schools (in Soibada). From these children, Aleixo Corte-Real was one of them, arose the social class of the Timorese educated in Europe, the Letrados . By 1910 the church was limited in its work, there were already eleven schools for 412 boys and two schools for 223 girls, plus four universities with 105 students and 153 female students. They taught 30 clergy and 141 teachers. This generation later formed a new Christian elite in the colony on which the Portuguese colonial power could rely. With the overthrow of the dictatorship of the Estado Novo in 1974, the new political ruling class grew out of it, and it still has a great influence in East Timorese society today.

By the Second World War , thanks to the tighter control of Portugal in the colony, there were no more major uprisings - a peace span that had never existed for so long in the past 400 years. It was only with the Japanese occupation of Portuguese Timor in 1942 that the Timorese began to rebel openly against the Portuguese. After the end of the Battle of Timor and the restoration of Portuguese rule over the colony, the Viqueque Rebellion was one last major uprising in 1959 . Here one suspects an Indonesian influence. In the same year, as a direct result of the uprising, the notorious Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado PIDE (Police for International Affairs and Defense of the State) began its work in the colony. The attempt by some fighters to proclaim a Timorese republic in Batugade in 1961 was quickly put down.

See also

literature

- Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo : A Guerra de Manufahi (1911-1912). Baucau 2012. (Portuguese).

- Jaime do Inso : Em Socorro de Timor. Lisbon 1913. (New editions: "Timor - 1912". Edições Cosmos, Lisbon 1939 and A última revolta em Timor 1912. Dinossauro, Lisbon 2004, OCLC 68189039 ) (Portuguese).

- René Pélissier : Timor en guerre - le crocodile et les Portugais (1847–1913). Éditions Pélissier, Montamets, Orgeval 1996, ISBN 2-902804-11-3 . (French)

Web links

- Travel report by Alfred Russel Wallace from his stay in Kupang 1857–1869 and Dili 1861 (English)

- Revolta Manufahi husi perspetiva Timorizasaun (The revolt of Manufahi from a Timorese perspective; tetum)

supporting documents

Main Evidence

- Frédéric Durand: Three centuries of violence and struggle in East Timor (1726-2008). (PDF; 243 kB), Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, (online), June 7, 2011, accessed on May 28, 2012, ISSN 1961-9898 .

- Geoffrey C. Gunn: History of Timor. Technical University of Lisbon (PDF file; 805 kB), accessed June 4, 2012.

- Revista da Armada: Jaime do Inso. ( Memento of August 14, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (Portuguese), accessed June 4, 2012.

- Monika Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. A critical study of the Portuguese colonial history in East Timor from 1850 to 1912 (= Abera Network Asia-Pacific, Volume 4). Abera, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-931567-08-7 (dissertation University of Heidelberg 1994, 347 pages, illustrations, 23 cm).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d M. Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. 1996, p. 269.

- ↑ a b G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 81.

- ^ A b c Douglas Kammen: Fragments of utopia: Popular yearnings in East Timor. In: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 40 (2) June 2009, pp. 385-408, doi : 10.1017 / S0022463409000216 .

- ↑ a b c d e Maj Nygaard-Christensen: The rebel and the diplomat - Revolutionary spirits, sacred legitimation and democracy in Timor-Leste . In: Nils Bubandt, Martijn van Beer (ed.): Varieties of Secularism in Asia: Anthropological Explorations of Religions, Politics and the Spiritual. Routledge, 2011.

- ^ Neil Deeley, Shelagh Furness, Clive H. Schofield: The International Boundaries of East Timor. 2001, ISBN 1-897643-42-X ( on Google Book Search )

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. P. 82.

- ↑ a b c d e f "Part 3: The History of the Conflict" ( Memento of the original from July 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.4 MB) from the "Chega!" Report by CAVR (English)

- ↑ a b c Australian Department of Defense, Patricia Dexter: Historical Analysis of Population Reactions to Stimuli - A case of East Timor ( Memento of September 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- ↑ TIMOR LORO SAE, Um pouco de história ( Memento of the original dated November 13, 2001 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ East Timor - PORTUGUESE DEPENDENCY OF EAST TIMOR ( Memento of February 21, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 94.

- ↑ M. Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. 1996, p. 135.

- ↑ a b c d G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 89.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. P.56.

- ^ A b c G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 85.

- ^ A b c G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 83.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. Pp. 83-84.

- ↑ a b c d G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 84.

- ↑ M. Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. 1996, pp. 134-136.

- ↑ a b Durand p. 5.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. Pp. 84-85.

- ↑ a b c d G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 86.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. Pp. 86-87.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h René Pélissier : Portugais et Espagnols en "Océanie". Deux Empires: confins et contrastes. ( Memento of the original from April 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Éditions Pélissier, Orgeval 2010.

- ^ A b c G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 87.

- ^ Revista da Armada: A história da presença da Marinha in Timor. ( Memento of April 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (Portuguese)

- ↑ a b c d G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 88.

- ↑ a b c d e f Durand, p. 6.

- ^ A b c G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. Pp. 88-89.

- ↑ Andrey Damaledo: Divided Loyalties: Displacement, belonging and citizenship among East Timorese in West Timor , pp. 27–30, ANU press, 2018, limited preview in Google Book Search

- ^ R. Roque: Headhunting and Colonialism: Anthropology and the Circulation of Human Skulls in the Portuguese Empire, 1870-1930 , pp. 19ff., 2010, ff. & Q = Deribate # v = onepage restricted preview in the Google book search

- ↑ Christopher J. Shepherd: Development and Environmental Politics Unmasked: Authority, Participation and Equity in East Timor , p. 46, 2013, limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ a b Frédéric B. Durand: History of Timor-Leste, p. 70, ISBN 978-616-215-124-8 .

- ^ The case of Alferes Francisco Duarte “O Arbiru” (1862-1899). (PDF; 386 kB), accessed on March 25, 2013.

- ↑ a b c History and Politics. - Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. P. 91.

- ^ A b c G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 92.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. Pp. 91-92.

- ^ A b c G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 93.

- ↑ a b c M. Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. 1996, p. 267.

- ↑ a b c d e f Durand, p. 7.

- ↑ Manuel Azancot de Menezes: As Revoltas de Manufahi em Timor-Leste , August 30, 2018 , accessed on August 30, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d e G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 95.

- ↑ a b M. Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. 1996, p. 268.

- ↑ Steve Sengstock: Faculty of Asian Studies. Australian National University, Canberra.

- ↑ a b G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 96.

- ^ A b c G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 98.

- ↑ a b c d G. C. Gunn: History of Timor. P. 97 after Pélissier: Timor en Guerre. Pp. 290-292.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. P. 98 ff.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. P. 100.

- ↑ Steven Sengstock: Reinado to live on as vivid figure in Timor folklore. In: The Canberra Times. March 17, 2008.

- ↑ Henri Myrttinen: Angry young men - post-conflict peace-building and its malcontents. Notes from Timor Leste. Available from Watch Indonesia! .

- ^ A b Heike Krieger: East Timor and the International Community: Basic Documents. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ Government of Timor-Leste: Administrative Division (English)

- ↑ M. Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. 1996, p. 272 ff.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. P. 99.

- ^ GC Gunn: History of Timor. P. 144.