Funu

With Funu ( Tetum for "war" ) the culture of ritual war on the island of Timor referred.

background

The island was traditionally split up into numerous small empires, which were only loosely connected by alliance systems. The rulers of the empires were the Liurais . In the dispute over fertile land, borders, wedding agreements or simply perceived disregard, there were repeated feuds , wars, conquests and headhunts . There were even fights for farmland between individual village communities. The high population pressure also forced the individual villages to constantly enlarge their territories at the expense of others. Even with the arrival of the two colonial powers Portugal and the Netherlands , this tradition did not change. Partly because the colonial rulers did not have the power to control them, and partly because the Europeans used the feuds between the rich to their advantage. It was only in the first half of the 20th century that colonial control could be expanded to such an extent that internal conflicts were suppressed. But both during the guerrilla war against the Japanese occupiers in World War II and during the struggle for independence against Indonesia and the unrest in East Timor in 2006 , centuries-old feuds between individual villages often broke out, which were hidden behind the new political conflicts. Even with the problem of today's gangs in East Timor, there are influences of the Funu, which the individual groups incorporate into their philosophy.

Based on research in New Guinea , where similar traditions existed, scientists see the strongly ritualized wars as a measure against the threat of overpopulation on the island. The direct victims of the fighting were less of a role than the dead, who were mourned due to the hunger after the devastation of the fields. Conquered areas could not be used immediately by the victors due to taboos, as they feared the revenge of the spirits. After all, these fallow areas were able to regenerate again, which counteracted leaching of the soil. The form of war led in particular to an increased child mortality rate among girls, whereby the balance between the sexes was kept regionally due to the low number of victims among the warriors. A large number of men brought about greater protection for their own population and the territory, which is why male descendants were of great importance.

War preparation

One could only go to war with the consent of the ancestral spirits . The priest ( Dato-lulik ) sacrificed a buffalo for this and questioned the spirits. If the ghosts did not accept the given reason for war, the reason had to be changed until the ghosts agreed. Every man now had to kill a chicken . If the chicken stretched its right leg up, the man would have to go into battle; if the chicken stretched its left leg, it was meant to protect women and children at home. The rejected warriors could question the oracle a second time if they wanted . If you were then allowed to fight, but there was a high probability of being wounded or killed, while the chosen ones from the first round were according to the belief invulnerable against all weapons.

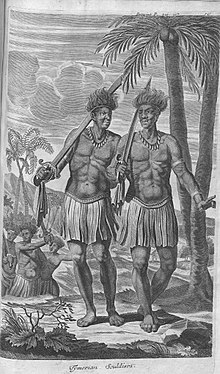

The battle

War cries (aclalak) were heard during the march . Magnificently decorated Meos stood in front of the warriors before the battle and began with war dances to heat the mood, extol the courage of their tribe and insult their opponents. After the Meos had withdrawn, the opposing parties fired at each other from a great distance - initially with bows and arrows, later with firearms. The battle ended with the death of a warrior. The aim of this warfare was not so much the field battle, but rather ambush ambushes in order to capture as many heads as possible of opposing warriors, women and children as slaves and cattle and sometimes also to devastate the enemy’s land. Women were only beheaded when they tried to flee from villages that had already been conquered, as this was contrary to morals.

After the fight

The warriors returning from battle were greeted with the traditional Likurai dance of the women. The captured heads were put on display. Those who had captured a head in battle received higher honors than those who had ambushed an enemy. The successful headhunters received the title Assuai (the brave) . The prepared heads were initially kept in the huts of the Assuai or were displayed in special holy ( lulik ) places. These could be large fig or tamarind trees, or the heads were wedged into walls or piles of rock. These places were considered to be contact areas with the spiritual world.

Heads kept in the home had to be offered something to eat at every meal. The head was later given to the liurai or village chief ( Dato ) who kicked him during a victory ceremony. The Assuai was given a bangle or a metal, round breastplate ( belak ) as a trophy , which he wore hung around his neck.

After a peace agreement, the heads were handed over to the dead man's family with great tears and lamentations. If a head was lost in the meantime, high compensation had to be paid. This also ended the hostilities between the groups. The peace was usually consolidated with a wedding or with blood brotherhood. This then required armed support in the event of war.

See also

- History of East Timor

- Slave trade in Timor

- Tara Bandu , Common Law in East Timor

literature

- José Ramos-Horta: Funu - East Timor's struggle for freedom is not over! Ahriman, Freiburg 1997. ISBN 3-89484-556-2

Individual evidence

- ↑ History of Timor ( Memento of the original from March 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Page 5, Technical University of Lisbon (PDF file; 805 kB)

- ↑ a b c d e f g Monika Schlicher: Portugal in East Timor. A critical examination of the Portuguese colonial history in East Timor from 1850 to 1912. Aberag, Hamburg 1996. ISBN 3-934376-08-8

- ^ R. Roque: Headhunting and Colonialism: Anthropology and the Circulation of Human Skulls in the Portuguese Empire, 1870-1930 , pp. 19ff., 2010, ff. & Q = Deribate # v = onepage restricted preview in the Google book search

- ^ A. McWilliam, L. Palmer and C. Shepherd: Lulik encounters and cultural frictions in East Timor: Past and present , pp. 309, 2014, Aust J Anthropol, 25: 304-320. doi: 10.1111 / taja.12101 , accessed December 12, 2017.