Marasmus

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| E41 | Alimentary marasmus Significant malnutrition with marasmus |

| E42 |

Kwashiorkor -Marasmus Significant energy and protein malnutrition |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

As marasmus ( adjectives marantic table, Maras table , marasmatisch ; of ancient Greek μαρασμός marasmós , German , becomes low, especially the removal of the life force in the high old age or by abzehrende disease ' ; formerly also Darrsucht or Darmdrüsenzehrung called) is referred to a protein deficiency or lack of energy, which for Reduction of all energy and protein reserves leads (also PEM protein-energy-malnutrition ).

The decline in strength affects not only the body , but also the mind and soul (with emotional upsets up to depression ). This definition criterion facilitates the differential diagnostic distinction between marasmus and other forms of malnutrition. The French analogue marasme means weariness with life, emaciation , exhaustion .

The marasmus is an exhaustion and exhaustion process that takes months to years. The numerous distinctions between malnutrition , malnutrition , failure to thrive , frailty , exhaustion , emaciation ( Latin Consumptio), old age atrophy , frailty , age reduction, exhaustion, cachexia , anorexia (anorexia), thinness, for malnutrition , for consumption , for Hungerdystrophie , for sickness and old age and to death fasts are not always observed.

In gerontology , Marasmus senilis describes the decline in physical functions with increasing age and is therefore also used as a term for a cause of death . This old age occurs particularly in old age.

causes

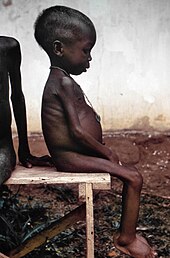

A marasmus occurs when a person suffers from general (quantitative and qualitative) malnutrition , i.e. from a lack of proteins , fats and carbohydrates . The body decays through a loss of body strength and substance. The disease is common in non-industrialized countries. It particularly affects children as soon as they are weaned from breast milk and then depend on food that does not provide them with enough energy. This effect is intensified by the fact that the malnutrition can impair the absorption and digestion of nutrients.

For example, children with marasmus show a deficiency in digestive enzymes and bile acids , which hinders their ability to absorb fats through the intestines. The decrease in enzymes and bile acids is attributed to the failure of their production in the pancreas or in the liver . The bile acids are also changed and made inoperable by the increased number of bacteria . A worm infestation and alcoholism are also considered causes of the marasmus.

Symptoms and diagnosis

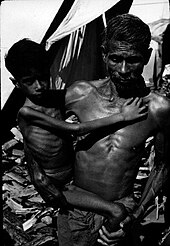

The most noticeable sign of malnutrition is great hunger and weight loss . The body needs its fat reserves to gain energy. In order to ensure the production of vital proteins for as long as possible, there is also a reduction in muscle mass, both in the skeletal muscles and in the heart muscles . The abdomen is usually bloated and the face becomes wrinkled. Affected children may look like old people. Furthermore, the patients suffer from diarrhea because the intestine atrophies . In contrast to kwashiorkor , in which the protein deficiency is leading, edema does not appear in marasmus. Blood pressure and heart rate (pulse) are decreased. The lack of food also greatly reduces the resistance of the immune system . As a result, the patient becomes vulnerable to numerous infections , some of which can be fatal.

Children who have suffered from marasmus show stunted growth ( marasmus infantilis ) or growth retardation ( developmental retardation ). They appear pre-aged ( progeria ). A negative effect on the intelligence of affected children in adulthood has so far been controversial. A marasmus is diagnosed as confirmed when a child is only 60% of its normal weight or less and no edema is present. If edema is present, a mixed form of global malnutrition and the protein deficiency Kwashiorkor can be assumed. This emaciation leads to starvation when the body weight has dropped to about half of the target weight. The smaller the body mass index , the greater the marasmus mortality from starvation ; a BMI of 13 kg / m² with a Vita minima is extremely dangerous .

The marasmus in young malnourished infants as a result of the complete disappearance of adipose tissue ( severe infant dystrophy ) is sometimes referred to as athrepsia or atrepsia . In addition, atrepsia in babies is the generic term for marasmus (due to lack of energy) and kwashiorkor (due to lack of protein).

Marasmus in home children

"Marasmus" is also occasionally referred to as psychological hospitalism , the "withering and ultimately extinction" ( René A. Spitz 1978) of children born healthy as a result of total emotional deprivation . Spitz called this condition " anaclitic depression ". In the past, up to 70% of foundlings died from this condition. This is also called decomposition .

treatment

The disease is treated (depending on the underlying disease ) according to a WHO scheme. This 10-step scheme is the same for marasmus and the related deficiency syndrome kwashiorkor . The patient's hypothermia caused by the loss of adipose tissue should be eliminated by warming. The body temperature should be monitored. Since low blood sugar levels often occur, these should be measured and, if necessary, glucose administered orally or intravenously . The dehydration that many patients experience should be countered with caution by giving oral rehydration solutions (to replenish fluids ). These solutions should contain less sodium and more potassium than normal rehydration solutions . This and the careful administration should prevent the patient's circulatory system from being overloaded, as the heart often does not perform well as a result of malnutrition.

In addition, the patient should be supplied with important vitamins and trace elements . The immune system of marasmus sufferers can be weakened to such an extent that an infection is present without the usual symptoms (e.g. fever). As a result, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given even if there are no symptoms . Treatment for malaria should also be considered. Since electrolyte disorders can occur in patients , they should be given potassium and magnesium as recommended by the WHO . The diet is to be carried out in two stages. The liver performance of the patients is usually reduced. As a result, the patient cannot adequately process rapidly supplied proteins. In the worst case, there is a risk of overloading with ammonia , as the conversion and breakdown of amino acids in the urea cycle can be disturbed. The result would be a life-threatening hepatic coma .

In addition, human attention is advised against the psychological and social consequences of hunger. After completion of the therapy, the occurrence of the malnutrition should be analyzed. If possible, work should be done with the family or community in which the patient lives in eliminating the causes.

Traditional disease concepts

In 1991, 150 lower-class women in the Pakistani city of Karachi were asked about their understanding of the disease as part of a study . Only a small minority attributed the disease to the medical causes of malnutrition (malnutrition, indigestion , malassimilation ) or malabsorption through diarrhea ( maldigestion ). The majority believed that the cause of the disease was contact with a woman who had a malnourished child or was in a state of ritual uncleanliness. The majority of those questioned attributed the triggering of the disease to spiritual factors. Likewise, the majority found medical treatment or increased food intake unsuitable to cure affected children. However, the women were very well aware of the children's poor chances of survival.

See also

- eating disorder

- Therapeutic fasting

- senility

- Hypotonia

- Hunger strike

- Inanition

- Starvation metabolism

- Zero diet

- Sarcopenia

- Tabes

Individual evidence

- ↑ Otto Dornblüth : Clinical Dictionary , 11th edition, Berlin, Leipzig 1922, p. 239.

- ↑ Ludwig August Kraus: Kritisch-Etymologisches medicinisches Lexikon , 3rd edition, Verlag der Deuerlich- und Dieterichschen Buchhandlung, Göttingen 1844, p. 591.

- ^ Wilhelm Pape , Max Sengebusch (arrangement): Concise dictionary of the Greek language . 3rd edition, 6th impression. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig 1914 ( zeno.org [accessed on May 28, 2019]).

- ↑ A. Müller, RW Schlecht, Alexander Früh, H. Still: The way to health: a faithful and indispensable guide for the healthy and the sick. 2 volumes, (1901; 3rd edition 1906, 9th edition 1921) 31st to 44th edition. CA Weller, Berlin 1929 to 1931, Volume 1 (1931), pp. 43-46 ( Darrsucht or intestinal gland consumption ).

- ↑ Harrison's internal medicine , 19th edition, Georg Thieme Verlag , Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3-88624-560-4 , Chapter 97: "Malnutrition and assessment of the nutritional status", pp. 553-559.

- ↑ The Merck Manual , 20th Edition, Merck, Sharp & Dohme , Kenilworth (New Jersey) 2018, ISBN 978-0-911910-42-1 , pp. 33-36.

- ^ German Book Association (Berlin, Darmstadt, Vienna): Handlexikon , Ullstein Verlag , Frankfurt am Main, Berlin 1964, p. 562.

- ^ Hexal Taschenlexikon Medizin , 2nd edition, Urban & Fischer , Munich, Jena 2000, ISBN 978-3-437-15010-4 , p. 468.

- ↑ Der Große Duden , Volume 5, Foreign Dictionary , 2nd Edition, Dudenverlag , Mannheim, Vienna, Zurich 1971, ISBN 3-411-00905-5 , p. 428.

- ^ Robert M. Youngson: Collins Dictionary of Medicine , Harper Collins Publishers, Glasgow 1992, incorrect ISBN 0583-315917 , p. 379: "Retardation of mental development".

- ↑ Langenscheidt's Concise Dictionary French , Part 1: French-German, Langenscheidt, Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Zurich 1983, ISBN 3-468-04151-9 , p. 369.

- ^ Lexicon Medicine , 4th edition, Naumann & Göbel Verlag, Cologne without year [2005], ISBN 978-3-625-10768-2 , p. 1064.

- ^ Roche Lexicon Medicine , 5th edition, Urban & Fischer , Munich, Jena 2003, ISBN 978-3-437-15156-9 , p. 1174.

- ↑ Dieter Palitzsch: Pediatrics , Ferdinand Enke Verlag , Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-432-93131-X , p. 46 f.

- ^ Lutz Mackensen: The modern foreign dictionary , 3rd edition, VMA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1988, p. 303.

- ↑ Die Zeit : Das Lexikon in 20 volumes , Volume 9, Zeitverlag , Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-411-17569-9 , p. 328 f.

- ↑ Lingen Lexicon in 20 volumes , Lingen-Verlag , Volume 12, Wiesbaden no year, p. 65.

- ↑ Der Sprach-Brockhaus , Eberhard Brockhaus Verlag , Wiesbaden 1949, p. 394.

- ↑ ICD -10 classification for marasmus in tuberculosis : A16.9. Source: Bernd Graubner: Alphabetical directory ICD-10-GM 2006 , Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag , Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-7691-3252-1 , p. 638; Edition 2013, ISBN 978-3-7691-3509-1 , p. 704.

- ↑ Willibald Pschyrembel: Clinical Dictionary , 254th edition, de Gruyter Verlag, Berlin, New York 1982, ISBN 3-11-007187-8 , p. 725.

- ^ Specialist dictionary of medicine , Manfred Pawlak Verlag, Herrsching 1984, ISBN 3-88199-163-8 , p. 274.

- ^ Walter Siegenthaler , Werner Kaufmann , Hans Hornbostel , Hans Dierck Waller (eds.): Textbook of internal medicine , 3rd edition, Georg Thieme Verlag , Stuttgart, New York 1992, ISBN 978-3-13-624303-9 , p. 1249-1255.

- ^ Duden : The Dictionary of Medical Terms , 4th Edition, Georg Thieme Verlag , Stuttgart, New York 1985, ISBN 3-13-437804-3 , p. 430.

- ↑ Gerhard Wahrig : German Dictionary , Bertelsmann Lexikon-Verlag , Gütersloh, Berlin, Munich, Vienna 1972, ISBN 3-570-06588-X , p. 2361.

- ↑ Emanuel Rubin, David Strayer: Environmental and Nutrional Pathology. In: Raphael Rubin, David Strayer: Rubin's Pathology. Philadelphia 2008, pp. 277-278.

- ↑ HC Mehta, AS Saini, H. Singh, PS Dhatt: Biochemical aspects of malabsorption in marasmus: effect of dietary rehabilitation. In: British Journal of Nutrition. 1984, Vol 51, pp 1-6; PMID 6418198

- ↑ Peter Reuter: Springer Clinical Dictionary , 1st edition, Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-34601-2 , p. 1127.

- ^ A b Emanuel Rubin, David Strayer: Environmental and Nutrional Pathology. In: Raphael Rubin, David Strayer: Rubin's Pathology. Philadelphia 2008, pp. 277-278.

- ↑ Günter Thiele (Ed.): Handlexikon der Medizin , Urban & Schwarzenberg , Munich, Vienna, Baltimore no year, Volume 3 (L − R), p. 1550.

- ^ William A. Coward, Peter G. Lunn: The Biochemistry and Physiology of Kwashiorkor and Marasmus. In: British Medical Bulletin. 1981, Volume 37, No. 1, pp. 19-24; PMID 6789923 .

- ↑ Maxim Zetkin , Herbert Schaldach (Ed.): Lexikon der Medizin , 16th edition, Ullstein Medical, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 978-3-86126-126-1 , p. 1240.

- ↑ Günter Thiele (Ed.): Handlexikon der Medizin, Urban & Schwarzenberg , Munich, Vienna, Baltimore no year, Volume 1 (A − E), pp. 167 and 170.

- ^ Peter Reuter: Springer Clinical Dictionary , 1st edition, Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-34601-2 , p. 159.

- ↑ Developmental Psychology - Erich Kasten, PDF 347 kB, here p. 5 f.

- ^ Dieter Palitzsch: Pädiatrie , Ferdinand Enke Verlag , Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-432-93131-X , p. 46.

- ↑ DocCheck : Flexikon : Keyword marasmus.

- ^ Olaf Müller, Michael Krawinkel: Malnutrition and health in developing countries. In: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005, 2; 173 (3), pp. 279-286, PMID 16076825 .

- ^ Dorothy Mull: Traditional perceptions of marasmus in Pakistan. In: Social Science and Medicine. 1991, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 175-191; PMID 1901666 .